For reference see a list of the personalities

connected with British foreign policy towards the Arab Middle East, 1914–19.

As we have seen, Sykes-Picot granted

Britain the right to administer Syria after it captured the Levant from the

Ottomans in 1918.In 1919, London conceded at the Paris

Peace Conference both Levantine entities to France

that moved quickly and, aware of Hashemite progress, settled on creating

Greater Lebanon.

Lebanon survived, become a republic under French supervision on August

24, 1920, promulgated a constitution on May 23, 1926, and elected a president,

Charles Debbas, that same year. The French mandate was terminated with

independence in 1943, and while the Sykes-Picot division of the Levant into two

states did not stabilize Syria because the Sunni population opposed

decentralization, France managed to muck everything up by further dividing that

hapless country into various statelets grouped within a federation that lasted

until 1924. Nationalist elements, led by French-educated intellectual voices,

ironically both Christian as well as Muslim, rejected the Mandate and fought

for independence.

Syria exploded in an anti-French uprising, but Lebanon held together

until 1958 when it skirted with a first major constitutional crisis that took

on confessional characters at a time when the Nasser phenomenon mobilized the

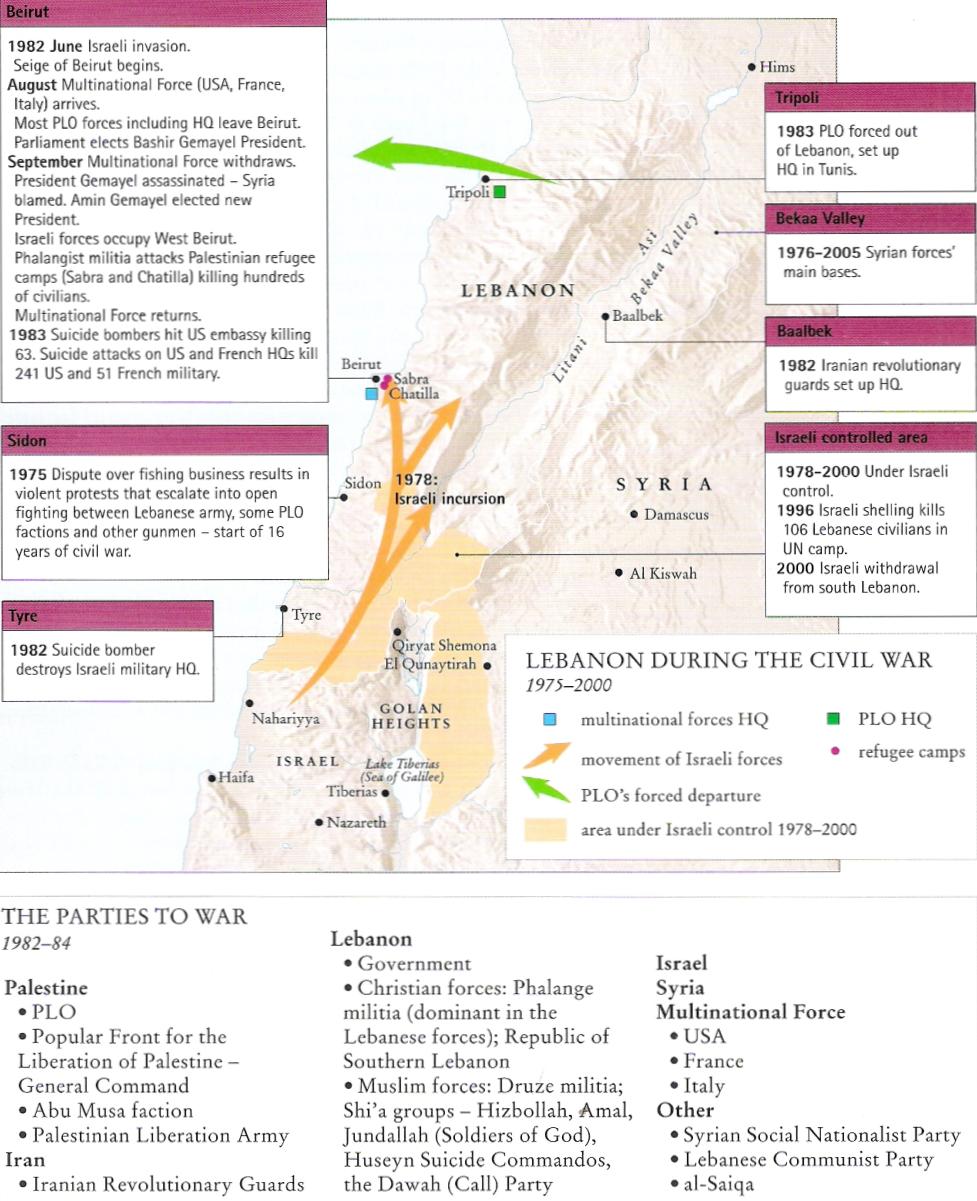

Arab world. The long-anticipated civil war came in 1975, accelerated by the

1967 Arab-Israeli War that poured Palestinian refugees in the fragile country,

even if latent domestic schisms were inherently present.

For winding to Sunday 1 November 2016 the clocks went back an hour in

Lebanon but, as one Twitterati wit had it on Monday, they went back 27 years.

That was when the Lebanese parliament managed to elect a president, after a

hiatus of 29 months. To do so they reached back to the last spasms of the

1975-90 civil war, to retrieve its most mercurial

protagonist, former General Michel Aoun, a Christian ally

of Hezbollah. This also means the new Government will lean closer to Syrian

President Assad.

Saad Hariri, the newly nominated prime minister of Lebanon, vowed

to work on forming a national accord government capable of facing the

country’s divisions which have paralyzed Lebanon for several years.

It is interesting of course that we have here both the so-called March 8

(with

Aoun) and the March 14 (Hariri) Alliance. While there are Christian parties

in both coalitions, the split is perceived in Lebanon and elsewhere as Shi’i

-Sunni.

In 2008 a battle between "March 8" and "March 14"

Alliance developed when Hezbollah-led

opposition fighters seized control of several West Beirut neighborhoods

from March 14 Alliance militiamen loyal to the government, in street battles

that left 11 dead and 30 wounded. The opposition seized areas were then

handed over to the Lebanese Army. The army also pledged to resolve the

dispute and has reversed the decisions of the government by letting Hezbollah

preserve its telecoms network and re-instating the airport's security chief.

The incident however was referred to as a family dispute and safely

filled away as "nonsectarian" and thus less dangerous (for more on

related issues see at the end).

The Lebanese political system is based on a sectarian division of

constitutional powers and administrative positions, guaranteeing the

representation of certain groups while also contributing to decision-making

paralysis.

The flaws of the sect-based governance system in part led Lebanon into

civil war. The 1989 Taif Agreement, which put an end to the war, reshuffled the

system (see below). Syria was made the postwar power broker and given

guardianship over Lebanon.

After Taif, a divisive tension arose between Lebanon’s two main Muslim

communities, the Sunnis and Shia. Syria managed the divisions while also

exacerbating them.

Sunni-Shia frictions sharpened after the assassination of Lebanon’s

prime minister (see below) and Syria’s 2005 withdrawal from the country. They

further intensified with the 2011 outbreak of the Syrian civil war.

As covered by me in 2005, the territory

that is now known as Lebanon was a creation of the post-World War One

settlement between the Great Powers, which led to the division of the Arab

territories of the former Ottoman Empire between Great Britain and France.1

France was assigned part of the Arab provinces and created the new

states of Syria and Greater Lebanon, renamed in the French-imposed constitution

of 1926 as the Republic of Lebanon.2

Nevertheless, the British at the time knew what they wanted, and they

got it: control over the oilfields of Mosul in Iraq;

unimpeded access from there to the Mediterranean; control of the Red Sea and

the Persian Gulf (which were the two vital maritime highways leading to the

Indian Ocean). To secure their interests, they naturally preferred to deal with

parties in the area, or concerned with the area, who also knew what they

wanted, and who were willing to make realistic accommodations achieve their

ends. During the war, the British had made a point of encouraging Arab

nationalist activity in Syria against the Ottomans; and it was partly through

British intermediaries that the Arab nationalists in Syria were put in touch with

Hashemite Hussein ibn Ali and his sons, which subsequently gave the

revolt in the Hijaz the extra dimension it needed to gain recognition as a true

Arab Revolt. After the war, however, it became clear to the British that the

claims of Arab nationalism were most urgently pressed either by romantic

dreamers who were unwilling to be taught that politics was the art of the

possible or by unprincipled schemers who were out to secure personal rather

than national interests. In either case, the nationalist claims, it was felt,

where they threatened to embarrass British interests, could be discounted at

negligible cost.

In their own mandated territories, which they called the Levant, the

French took the same attitude as the British: they were willing to attend to

reasoned and concrete demands by parties who knew what they wanted, but had no

patience for the claims and clamours of those who did

not. In Mount Lebanon and the adjacent parts of the old Vilayet of Beirut, the

Maronites - a Christian communion with a long tradition of union with the Roman

Catholic church in Europe - were one party whose demands the French were prepared

to listen to. Of all the Arabs, barring only individuals or politically

experienced princely dynasties, they appeared to be the only people who knew

precisely what they wanted: in their case, as they put it, a 'Greater Lebanon'

under their paramount control, separate, distinct and independent from the rest

of Syria. Behind them, the Maronites had a rich and eventful past which will be

reviewed as a separate story in due course.

In 1861, with the help of France, they had already secured a special

political status for their historical homeland of Mount Lebanon as a Mutasarrifate, or privileged sanjak

(administrative region), within the Ottoman system, under an international

guaranty. Since the turn of the century, however, the Maronites had pressed for

the extension of this small Lebanese territory to what they argued were its natural

and historical boundaries: it would then include the coastal towns of Tripoli,

Beirut, Sidon and Tyre and their respective

hinterlands, which belonged to the Vilayet of Beirut; and the fertile valley of

the Bekaa (the four Kazas, or administrative districts,

of Baalbek, the Bekaa, Rashayya and Hasbayya), which belonged to the Vilayet of Damascus.

According to the Maronite argument, this 'Greater Lebanon' had always had a

special social and historical character, different from that of its

surroundings, which made it necessary and indeed imperative for France to help

establish it as an independent state.

By the end of the Young Turk occupation in 1918, a general consensus had

settled amongst a class of urban, largely Christian politicians on the

‘natural’ boundaries of the Republic (which were predicated on those of the Ma‘nite and Shihabite Emirate).

Bulus Jouplain (aka Nujayam)

(in La Question du Liban, Paris 1908) had already suggested the enlargement of

the ‘Lebanese nation’ within Syria in precisely this manner, even though Jabal

‘ā mil was conspicuously left out.

It is often forgotten that these borders were first drawn in December

1918 by the Administrative Council under Habīb Pasha

Sa‘d. Under the subsequent French Mandate, Article 1 of Decree 318 of August

1920 formally codified the geographic borders of the Grand Liban composed of

the Cazas of Ba‘albak, the Biqa

‘, Rashaya and Hasbaya and the Sanjaks of Beirut,

Sidon and Tripoli. As the sole state in the region, May 23, 1926 Constitution

cannot be reduced to a ‘gift’ to the Maronites as its detractors are wont to

claim. The very boundaries of the new state (by adding Tripoli, Beirut, Sidon

and the Bekaa) – ironically supported by Patriarch Huwayyak

yet opposed by most Maronites, was bound to dilute Christian demographic

dominance which had prevailed in the Petit Liban from 1860–1914.The

overwhelming majority of war-scarred Christians had expressed their support for

an independent Lebanese state during the the

Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey questionnaire in 1919, but the

borders remained a contested issue as a small Lebanon was not deemed viable

economically, and given that the Orthodox preferred a different set of

boundaries which would have granted them, as opposed to the Maronites, the

status of the largest Christian demography. The 1919 commission revealed that

all Lebanese Christians wanted independence (with or without a French Mandate).

The Orthodox were the only Lebanese Christian community favoring a union with

parts of Syria. given the high number of Orthodox in the ‘wadi Nasaara’ region.

In the end, Lebanon’s constitution introduced a novelty: confirming

prior decrees passed by the High Commission, the 1926 Constitution is the only

one to explicitly delineate a nation’s borders in the very first Article 1.

This innovation came as a fait accompli report to the Muslim (and occasional

Christian) opposition to the new state. At the same time, the creation of the

enlarged Republic in 1920 also signaled Lebanon’s fuller, if still incomplete,

adoption of French secularism. In the decades to come, the political identity

of the new state, however, would have to pass through a more arduous process of

debate, argumentation and constant re-negotiation of the terms of the

prospective social contract. In navigating the course from this tempestuous sea

of virulent nineteenth-century communalisms and identities in flux to a more

stable shore of nationhood, intellectuals and politicians oriented themselves

according to past domestic and foreign lodestars. To the likes of Jamīl Ma‘luf, Yusuf al-Sawda,

Makram Zakour, Khalil Saadeh (and his son antun), or But.rus al-Bustanī’s son Salīm al-Bustanī, national

sovereignty and secularism, it seemed, were the hallmarks of progress and the

ineluctable destiny of the age. This conviction was further strengthened by a

large Lebanese exile community in France, the Americas and Egypt who acted as

vocal ambassadors of Republicanism.

While France had strong sympathies for the Maronites, the French

government did not support their demands without reserve. In Mount Lebanon, the

Maronites had formed a clear majority of the population. In a 'Greater

Lebanon', they were bound to be outnumbered by the Muslims of the coastal towns

and their hinterlands, and by those of the Bekaa valley; and all the Christian

communities together, in a 'Greater Lebanon', could at best amount to a bare

majority. The Maronites, however, were insistent in their demands. Their

secular and clerical leaders had pressed for them during the war years among

the Allied powers, not excluding the United States. After the war, the same

leaders, headed by the Maronite patriarch Elias Hoyek in person, pursued this

course at the Paris Peace Conference; and in the end, the French yielded.

Following the San Remo conference and the defeat of King Faisal's

short-lived monarchy in Syria at the Battle of Maysalun,

the French general Henri Gouraud subdivided the

mandate of Syria into six states. They were the states of Damascus (1920),

Aleppo (1920), Alawites (1920), Jabal Druze (1921), the autonomous Sanjak of

Alexandretta (1921) (modern-day Hatay), and the State

of Greater Lebanon (1920) which became later the modern country of Lebanon.The flag of this new Lebanon was to be none other

than the French tricolor itself, with a cedar tree - now hailed as the glorious

symbol of the ancient country since Biblical times - featuring on the central

white.

Following the establishment of the State of Greater Lebanon, the French

turned to deal with the rest of their mandated territory in the Levant, where

they were at a loss what to do. In the case of Lebanon, the Maronites had

indicated precisely what they wanted. Elsewhere, no community seemed willing to

speak its mind unequivocally, which left the French to their own devices. To

begin with, in addition to Lebanon, they established four Syrian states: two of

them regional, which were the State of Aleppo and the State of Damascus; and

two of them ethnoreligious, which were the State of the Alawites (French Alouites) and the State of Jebel Druze.

In July 1922 then, France established a loose federation between three

of the states: Damascus, Aleppo, and the Alawite under the name of the Syrian

Federation (Fédération syrienne). Jabal Druze, Sanjak

of Alexandretta, and Greater Lebanon were not parts of this federation, which

adopted a new federal flag (green-white-green with French canton). On December

1, 1924, the Alawite state seceded from the federation when the states of Aleppo

and Damascus were united into the State of Syria. In 1925, a revolt in Jabal

Druze led by Sultan Pasha el Atrash spread to other

Syrian states and became a general rebellion in Syria. France tried to

retaliate by having the parliament of Aleppo declare secession from the union

with Damascus, but the voting was foiled by Syrian patriots. Flag of the Syrian

Republic (1932-58, 1961-63). On May 14, 1930, the State of Syria was declared

the Republic of Syria and a new constitution was drafted. Two years later, in

1932, a new flag for the republic was adopted. The flag carried three red stars

that represented the three districts of the republic (Damascus, Aleppo, and

Deir ez Zor). In 1936, the Franco-Syrian Treaty of

Independence was signed, a treaty that would not be ratified by the French

legislature. However, the treaty allowed Jabal Druze, the Alawite (now called

Latakia), and Alexandretta to be incorporated into the Syrian republic within

the following two years. Greater Lebanon (now the Lebanese Republic) was the

only state that did not join the Syrian Republic.

Thus the two sister republics came into being, Lebanon and Syria; both

under French mandate, sharing the same currency and customs services, but

flying different flags, and run by separate native administrations under one

French High Commissioner residing in Beirut. Before long, each of the two

sister countries had its own national anthem. But are administrative

bureaucracies, flags and national anthems sufficient to make a true

nation-state out of a given territory and the people who inhabit it?

To the Maronites and many other Christians in Lebanon, there were no

doubts about the matter. The Lebanese were Lebanese, and the Syrians were

Syrians, just as the Iraqis were Iraqi, the Palestinians Palestinian, and the

Transjordanians Transjordanian. If the Syrians, Iraqis, Palestinians or

Transjordanians preferred to identify themselves as something else, such as

Arabs united by one nationality, they were free to do so; but the Lebanese

remained Lebanese, regardless of the extent to which the outside world might

choose to classify them as Arabs, because their language happened to be Arabic.

Theirs, it was claimed, was the heritage of ancient Phoenicia, which antedated

the heritage they had come to share with the Arabs by thousands of years.

Theirs, it was further claimed, was the broader Mediterranean heritage which

they had once shared with Greece and Rome, and which they now shared with

Western Europe. They also had a long tradition of proud mountain freedom and

independence which was exclusively theirs, none of their neighbors ever having

had the historical experience.

Unfortunately for the Maronites, however, not everybody in Lebanon

thought or felt as they did. There were even many Maronites who dissented and

freely expressed their divergent views. After all, who could reasonably deny

that Lebanon, as a political entity, was a new country, just as the other Arab

countries under French or British mandate were? Certainly, Lebanon was as much

a new country as the others, but with an important difference: it had been

willed into existence by a community of its own people, albeit one community

among others. Moreover, those among its people who had willed it into existence

were fully satisfied with what they got and wanted the country to remain

forever exactly as it had been finally constituted, without any territory added

or subtracted.

The Syrian Republic, it is true, had also been finally put together in

response to nationalist demand; in fact, following a nationalist uprising which

lasted more than two years (1925-7), provoking a French bombardment of

Damascus. In Syria, however, the nationalists were only partly satisfied with

what they got and continued to aspire for much more. They knew what they did

not want rather than what they wanted, and what they were opposed to more than

what they were in favor of. For a brief term, they had had an Arab kingdom,

with its capital in historical Damascus, once the seat of the great Umayyad

caliphs and the capital of the first Arab empire. The French had destroyed

their kingdom and established statelets on its territory, among them Lebanon.

The Maronites, they argued, were perhaps entitled to continue to enjoy the sort

of autonomy they had enjoyed since the 1860s in the Ottoman Sanjak of Mount

Lebanon, although they had no real reason to feel any different from other

Syrians or Arabs. Or as some argued,

they would have had no right securing for their Greater Lebanon-Syrian

territory which had formerly belonged to the vilayets of Beirut or Damascus,

and which had never formed part of their claimed historical homeland.

The mandate years set in motion dynamics that would accelerate and reach

full fruition following independence, in particular the heavy reliance of the

economy on trade and services, with a minimalist state that relied on religious

and other non-governmental institutions to provide basic social services.3

The new lands that came under the expanded control of the Maronites

contained large numbers of both Sunni and Shi'a Muslims. The Sunni, in

particular, strongly objected to Maronite rule over what they considered to be

their lands. In response, and in an attempt to maintain control, the Maronites

eventually struck a deal with Shi'a leaders. In return for a large degree of

their own freedom of political action in the south, the Shi'a agreed to accept

Maronite control. The Shi'a had long lived in the region as a minority group

persecuted by the Sunni majority and, at the very least, sought to bring that

practice to an end. Their efforts were successful. As a result of their support

of the Maronites, the Shi'ites soon materialized as a distinct and important faction

in Lebanon; a position they had not been able to assume previously. Indeed,

beginning in 1926, the French allowed the Shi'ites to create their own,

autonomous, religious-based infrastructure and to practice their religion

without outside interference.4

As expected, the Christian Maronites emerged as the dominant political

actor in the mandate. Out of respect for the diverse factions however,

political power was divided among the various religious entities. In addition,

certain political arrangements were established in an attempt to maintain

regime stability and legitimacy (see 'National Pact' below).

The economic and social changes that occurred during the mandate led to

the emergence of variety of important new social formations, including a

rapidly growing labor movement, a women’s movement, new kinds of religious

organizations and movements, as well as new mass political parties, such as the

Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) and the Lebanese Kata’ib

Party (LKP), a rightwing proto-fascist organization that recruited Christian

youth. Discontent with the mandate begin to grow, especially after the onset of

the Great Depression, and the colonial government was forced by popular

pressure to institute a limited public works program to provide employment and

stimulate the moribund economy. However, France’s own economic and political

troubles during the 1930s limited the assistance the metropole was willing to

provide to a minor French colony, and demands for greater autonomy and

independence were growing by the time the Second World War broke out.

Following World War II, Lebanon began to modernize. This process had a

significant impact on all members of the state both socially and politically.

And, this was particularly true of the Shi'ites. The infrastructure of the

entire country began to both expand and improve. Transportation was made

easier, which contributed to an influx of Shi'ites into Beirut, searching for a

better life. Nonetheless, an almost immediate result was the rapid expansion of

the "Belt

of Misery."

Modernization impacted the media and the availability of information

among the entire population. Radio and television contributed to a growing

awareness among the Shi'a that their position within Lebanon was not what it

could be, in a way that they had not been impacted before. This exacerbated

their sense of relative deprivation and made the lack of social mobility, all

the more painfully obvious. Most Shi'a in Lebanon saw an almost continuous

sequence of what they perceived of as unjust government and a society that

simply did not seem to work for them. And, Sunni hegemony within the Islamic

community, placing the Shi'a in a sort of permanent minority status among the

faithful, tended to exacerbate these problems.

Thus during the 1940s and 1950s, a significant gap was growing,

economically, politically, and socially, between the Shi'ites and the rest of

the country, largely because the government in Beirut tended to neglect them.

Perhaps worse yet, semi feudal, landowning elites in the south were far more

interested in their own personal gain than they were in the welfare of the

Shi'a community as a whole. As a result, whereas the rest of Lebanon was

modernizing, the Shi'ites lacked basic necessities: schools, hospitals, roads,

and even running water in many instances. In comparison with the prospering

areas of the Sunnis and Christians, their standard ofliving

was medieval. As an example, in an analysis prepared in 1943, at the time of

Lebanon 's independence, it was noted that there was not one hospital in the

entire south Lebanon area. The closest health clinic was in Sidon , Tyre , or Nabatiyya, all in the

middle or northern sections of the country. Further, the availability of water

for irrigation or human consumption was a persistent problem in the region.

Nonetheless, there was very little that the new Lebanese state was willing or

was able to do for the minority and increasingly marginalized Shi'a community.5

Following the fall of France in 1940, the French Empire was split

between those colonies that supported the new Vichy regime under Marshal

Petain, and those who backed the Free French forces of General de Gaulle.6

The colonial bureaucracies of Syria and Lebanon both declared for Vichy,

which led to British fears that they would serve as a bridgehead for German

control of the Middle East, a fear which grew after the 1941 coup in Iraq which

overthrew the British-backed regime and brought to power the nationalist Rashid

Ali, who had opened lines of communication with the Nazis. In June 1941, the

Allies launched an invasion of Syria and Lebanon and swiftly defeated Vichy

forces, returning the colonies to Free French control. However, the weakness of

the Free French administration, growing opposition to colonial rule, and

pressure from the British, forced the French to agree to a rapid transition to

independence. In 1943, a new Lebanese government, under President Beshara

al-Khoury and Prime Minister Riad al-Solh, declared independence and revised

the Lebanese constitution to remove all references to the mandate. In an

attempt to renege on its promises, the French arrested and imprisoned the new

government, and imposed direct rule, until a popular revolt and British

pressure forced them to release and recognize the new, independent government

on November 22nd 1943. Allied troops remained in Lebanon and Syria for another

three years however, and it was only after further protests and an abortive

French attack on the Syrian capital Damascus, that the full withdrawal of

foreign troops was realized in early 1946.

Beshara al-Khoury’s presidency was marked by a number of important

developments which shaped the postcolonial landscape of Lebanon.7

At the very beginning of his term, he reached a verbal agreement with

Prime Minister Riad al-Solh on the sectarian contours of Lebanese politics,

known as the ‘National Pact’. This agreement essentially divided all political

posts in the government and state bureaucracy along sectarian lines, according

to fixed quotas that supposedly matched the demographic weight of each

sectarian group.8

The presidency itself would always be held by a Maronite Christian, the

premiership by a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of the national parliament would

always be a Shi’ite Muslim, while seats in the national parliament would be

apportioned in a 6:5 ratio of Christians to Muslims. The National Pact guided

the form of Lebanese politics until its revision at the end of the civil war,

while the revised constitution of 1943 promised both respects for individual

rights, and pledged to uphold sectarian politics, two positions which were not

always easily reconciled. In addition to the National Pact, an elite consensus

around Lebanon’s economic and foreign policies rapidly developed. The former is

the subject of Chapter One, and a fuller discussion will be left for that

chapter, but in essence it entailed an agreement to quickly dismantle wartime

economic controls, and to build a largely unregulated, externally-oriented,

laissez-faire economy that centered on trade, finance and services. With

respect to foreign policy, there was an agreement to maintain Lebanese

neutrality in inter-Arab affairs and conflicts, and to avoid overtly allying

with any one regional power. In practice, given the growing economic

connections that the new republic was developing with the Gulf kingdoms and

with Western states, Lebanon gravitated towards the emerging ‘conservative’

camp in Arab politics.

Thus during the 1940s and 1950s, a significant gap was growing,

economically, politically, and socially, between the Shi'ites and the rest of

the country, largely because the government in Beirut tended to neglect them.

Perhaps worse yet, semi feudal, landowning elites in the south were far more

interested in their own personal gain than they were in the welfare of the

Shi'a community as a whole. As a result, whereas the rest of Lebanon was

modernizing, the Shi'ites lacked basic necessities: schools, hospitals, roads,

and even running water in many instances. In comparison with the prospering

areas of the Sunnis and Christians, their standard of living was medieval. As

an example, in an analysis prepared in 1943, at the time of Lebanon 's

independence, it was noted that there was not one hospital in the entire south

Lebanon area. The closest health clinic was in Sidon, Tyre,

or Nabatiyya, all in the middle or northern sections

of the country. Further, the availability of water for irrigation or human

consumption was a persistent problem in the region. Nonetheless, there was very

little that the new Lebanese state was willing or was able to do for the

minority and increasingly marginalized Shi'a community.9

At another level, Shi'a religious leaders and many members of the lay

public did not trust the government, which they perceived of as a secular,

unworthy, activity. As a result, members of the Shi'ite community purposely

held back from participating in public affairs, even within those fields that

were within reach to them professionally.10

In 1958, a civil war erupted in Lebanon, largely as a result of the

increased factionalism caused by the political arrangements established over 20

years earlier. Predictably, the Christian community had developed an

increasingly pro-Western orientation, gaining the favor of not only France, but

the United States. This orientation came into conflict with the growing

pan-Arab ideology of the Sunni Muslims throughout the region. Ultimately, U.S.

troops intervened in the fighting and order was established when the leader of

Lebanon's army,the now re-elected Fouad Chehab, was

elected president. 11

Helou’s tenure, was marked by a number of major domestic and regional

crises, including the Intra Bank crash of 1966, the June War of 1967, and the

escalating tensions between the Lebanese security forces and Palestinian

guerrilla fighters operating from Lebanese territory. The financial crisis that

accompanied the collapse of the country’s largest bank, Intra Bank, marked the

onset of an extended period of economic instability and uncertainty, that is

dealt with more extensively in Chapter Three. Such instability was heightened

by the regional conflict in 1967, the June War, which saw Israel launch a

preemptive strike on several Arab states, rapidly defeating their armed forces

and capturing large swathes of territory in the process. In the aftermath of the

June War, Lebanon began to be drawn into the Arab-Israeli conflict more

directly, as a result of the rising strength and importance of the Palestine

Liberation Organization (PLO). Founded in 1964, the PLO had been marginalized

hitherto by the major Arab states, especially Egypt, which sought to monopolize

the Palestinian struggle for their own geostrategic ends. In the wake of the

humiliating defeat of the Arab states in the June War, however, the PLO gained

a greater degree of operational autonomy, arguing that only a truly

Palestinian-led popular resistance movement could defeat Israel, and drawing on

the struggles of oppressed.

In 1970 Suleiman Franjiyyeh, another

compromise candidate, was elected president as elite divisions over how best to

respond to the mounting social and economic crisis, as well as the Palestinian

presence, became more entrenched. During the early 1970s the economic situation

remained desperate, as inflation soured, unemployment rose and the protracted

crisis of rural Lebanon, in which small peasants and agricultural laborers were

being increasingly squeezed by powerful agri-business monopolies and wholesalers.12

Waves of migration to the capital increased, and the already inadequate social

and infrastructural services began to buckle under the strain. Net migration

out of the country increased to over 10,000 per year, as educated middle-class

professionals with the means to do so emigrated to the Gulf states or to the

West, depriving the country of thousands of engineers, doctors, teachers and

other professionals.

Then came, Ayatollah Khomeini who sought to connect the Shi'a past, with

the Shi'a nature, and contend that “Western” thought and values are dangerous.

On April 18, 1983, the U.S. Embassy in Beirut was destroyed in a massive

explosion carried out by a Hezbollah suicide bomber, killing a total of 63. Six

months later, a U.S. Marine compound located near the Beirut airport and a

French military compound four miles away were bombed within seconds of one

another killing 299.

The 1989 Taif

Agreement marked the beginning of the end of the fighting. In January 1989,

a committee appointed by the Arab League began to formulate solutions to the

conflict. In March 1991, parliament passed an amnesty law that pardoned all

political crimes prior to its enactment.13 In May 1991, the militias were

dissolved, with the exception of Hezbollah, while the Lebanese Armed Forces

began to slowly rebuild as Lebanon's only major non-sectarian institution.13

Religious tensions between Sunnis and Shias remained after the war.14

At the end of the civil war, the now elected General Aoun headed one of

two rival governments. In 1989 he launched a “war

of liberation” to drive Syria out of Lebanon, and then went to war against

the Lebanese Forces, the main Maronite Christian militia, a bitter episode of

intra-Maronite fratricide. Rescued by the French and whisked into exile in

Paris in 1990, he left much of what was left of Beirut in ruins.

In 2005, the Sunni prime minister behind the reconstruction of the city,

Rafiq Hariri, was

assassinated after a political confrontation with Syria, for which four members of Hizbollah,

the Iran-backed Shia movement, are on trial in absentia in The Hague. Gen Aoun

returned from exile after this seismic regicide, as Lebanese took to the

streets and Syrian forces withdrew. Taking his place alongside the warlords in

suits that make up Lebanon’s political elite, he promptly made a pact with Hizbollah and peace with Syria. His fans see him as

Lebanon’s De Gaulle. His critics wonder at his ability to turn on a sixpence.

Iran as well as Syria counts this Christian’s election a victory in the

region-wide struggle of the Tehran-backed Shia Arab axis against the Sunni camp

led by Saudi Arabia. Ali Akbar Velayati, an adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader

Ali Khamenei, hailed “a great triumph for the Islamic Resistance in Lebanon [Hizbollah] and for Iran’s allies and friends”.

But Aoun owes his apotheosis not just to Hizbollah.

The decisive turn came when (the above mentioned) Saad Hariri, son of the slain

Rafiq, a former premier himself and head of the Sunni Future party, gave the

general his votes. Given the still livid wounds of Lebanon’s war and new rifts

opened by civil war next door in Syria, where Hizbollah

fights for the regime and the Sunni back the rebels, it is something that the

Lebanese can come together. Given Lebanon’s hollowed out institutions, it is

also important to fill the presidency that embodies the special status of

Christians. Under a postwar power-sharing pact brokered by Saudi Arabia, a

parliament split 50-50 between Muslims and Christians elects a Maronite

president, who names an executive Sunni prime minister, who must then be

confirmed by parliament, which is always headed by a Shia.

Michel Aoun, however, comes

into office with two unrealistic objectives: reclaiming the Maronite

political prestige and power lost in 1989 and empowering the state. The Taif

accord, which ended the 15-year civil war, stripped most of the powers of the

Lebanese presidency, a post reserved for Christian Maronites, and invested them

in the office of the prime minister, traditionally held by a Sunni. Aoun's

second stated objective is to reform inefficient and corrupt state

institutions. It will be very challenging for him to achieve either. War and

demographics have made the Maronite political-preeminence impossible. Compared

to Muslims, demographic trends do not favor Lebanese Christians, with the

latter numbering less than 40 percent of the population (this estimate is based

on the voter registry). Nor will Aoun be able to reform a patronage system in

which all political stakeholders including his own ministerial and

parliamentary blocs and large swathes of Lebanon's citizens are invested in its

preservation. Moreover, overcoming these challenges requires the temperament of

a conciliator-in-chief who is able to exact concessions from his opponents

through compromise, rather than confrontation. Aoun's track record proves he

does not have it.

Lebanon has escaped most of the mayhem sweeping the region. But this

presidential breakthrough, if such it is, does not look like the harbinger of a

luminous future.

In fact, there might be a looming crisis for Lebanon’s ruling elite,

exposing the fiction at the heart of the country’s politics.

What causes violent conflicts around the Middle East? All too often, the

answer is sectarianism, Joanne Randa Nucho argues in

her recent book Everyday Sectarianism in Urban Lebanon. Suggesting that various

groups interpret the past in different ways. (Nucho,

2016, p. 31.)

True, few Lebanese politicians have weathered their country’s rolling

political storms better than Michel Aoun, who rose from warlord to military

commander to prime minister at the end of the country’s lengthy civil war

before Syrian warplanes bombed him into exile in 1990. Having made peace with

his former enemies, he returned years later to lead the most powerful Christian

party in Lebanon. On October 31st he became the country’s 13th president.

It has taken Lebanon more than two years and 45 failed attempts to elect

a president. The political deadlock has paralyzed decision-making and crippled

basic services in a country already buckling under the strain of 1m Syrian

refugees. It has also exposed the clunky inadequacies of Lebanon’s political

system.

When it was first carved out of the crumbling Ottoman Empire, as we have

seen, Lebanon was intended as a haven for Christians in the Middle East. Yet

their numbers have since dwindled after decades of war, emigration and low

birth rates. But their political clout remains. Before the civil war of

1975-1990, Lebanon’s Christians enjoyed six reserved parliamentary seats to

every five given to Muslims. The allocation was made on the basis of a census

in 1932. Academic studies suggest that, at the time, Christians made up just

half the resident population but their numbers were inflated by questionable

counting immigrants (most of whom were Christians).

Under the Taif accords (see above) that ended the war, the ratio of

seats was adjusted to parity–the defeated Christians were given five seats for

every five for Muslims. It was clear that Christians were still being

over-represented, but it was hard to say so definitively as there had been no

census since 1932.

Official government figures show just how lopsided this arrangement has

now become. The data, taken from the voter registry, reveal that only 37% of

Lebanese voters are Christian. It is little wonder that many fear a new census

may inflame tensions in a country deeply divided along sectarian lines.

Voter registration lists, which include information on the religious

affiliation of the country’s 3.6m eligible voters initially were posted on a

website belonging to the Interior Ministry. Although they have since been taken

down.

Based on that, the data in the above chart show that Maronite Catholics,

once the largest sect in Lebanon, now make up only 21% of voters. That crown

has passed to the Shias, now 29% of those listed, followed closely by the

Sunnis, who make up 28%. Given their lower birth rates and higher rates of

emigration, Christians are likely to be an even smaller share of the general

population than they are of voters. Yet while the Sunnis and Shias each have 27

seats in the 128-member legislature, the Maronites have 34.

Whenever Lebanon erupts in violence, efforts are made to tinker with,

though not fundamentally alter, these imbalances. The Taif Agreement stripped

the Maronite presidency of much of its original power and strengthened the

roles of both prime minister and Speaker of parliament, which are always held

by a Sunni and Shia, respectively. Another agreement

in Doha after the above mentioned battle between "March 8" and

"March 14" Alliance flared up in Beirut in 2008 saw the Shia-led

opposition under Hizbullah win the right to veto

major decisions. Parliament’s dysfunction, seen in its inability to elect a

president for more than two years, is partly a product of these power-sharing

agreements.

Dally as the parliamentarians may, the fine underpinning Lebanon’s

political system will only become more egregious. Records of voter age also

included in the registry show how Muslims make up a large majority of the

country’s young (chart beow). So Christians will find

their control over half of parliament even harder to justify in the years to

come. Try as he may, Aoun will face an uphill battle if he attempts to claw

back the presidential powers lost by Christians at Taif.

The change will be hard, though. For example, the Christians have half

of parliament, the Sunnis have the prime minister’s office and Hizbullah is too busy in Syria. Yet the men who run Lebanon

have no interest in renegotiating the status quo it seems.

Another problem looms for tiny Lebanon. Since the civil war began in

neighboring Syria, Lebanon has

taken in 1m refugees, who are now roughly a quarter of the population. The great

majority of them are Sunni, making their absorption as citizens impossible

without up-ending the already strained sectarian balance. Lebanon faced a

similar conundrum over the 450,000 Palestinian refugees who entered it from

Israel and Palestine from 1948 inwards. Rather than integrate them, the

government issued repressive laws limiting their ability to get work, creating

an underclass where radicalism was free to fester.

Christians in Lebanon fear, with good cause, that re balancing the

country along new sectarian lines will leave them a depleted minority in their

own land. Yet the current order of parliamentary over-representation may be

sustainable for another decade or even two; it also may not. Stony silence on

the matter appears to be the government line. But ignoring impending crises

such as these in the Middle East has a tendency to lead to bloodshed.

Lebanon chronology of key

events:

|

1920 September

- The League of Nations grants the mandate for Lebanon and Syria to France,

which creates the State of Greater Lebanon out of the provinces of Mount

Lebanon, north Lebanon, south Lebanon and the Bekaa. 1926 May

- Lebanese Representative Council approves a constitution and the unified

Lebanese Republic under the French mandate is declared. 1940 -

Lebanon comes under the control of the Vichy French government. 1941 -

After Lebanon is occupied by Free French and British troops in June 1941,

independence is declared on 26 November. 1943 March

- The foundations of the state are set out in an unwritten National Covenant

which uses the 1932 census to distribute seats in parliament on a ratio of

six-to-five in favour of Christians. This is later

extended to other public offices. The president is to be a Maronite

Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim and the Speaker of the Chamber

of Deputies a Shia Muslim. Independence 1943 November-December

- Free French forces detain members of the recently-appointed government,

which had declared an end to the mandate, before releasing them on 22

November, henceforth known as independence day. France agrees to transfer

power to the Lebanese government from 1 January 1944. 1957 -

President Camille Chamoun accepts the Eisenhower Doctrine, announced in

January, which offers US economic and military aid to Middle Eastern

countries to counteract Soviet influence in the region. 1958 -

Faced with increasing opposition which develops into a civil war, President Chamoune asks the US to send troops to preserve Lebanon's

independence. The US, mindful of the recent overthrow of the Iraqi monarchy,

sends marines. Arab-Israeli war 1967 June

- Lebanon plays no active role in the Arab-Israeli war but is to be affected

by its aftermath when Palestinians use Lebanon as a base for attacks on

Israel. 1968 December

- In retaliation for an attack by two members of the Popular Front for the

Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) on an Israeli plane in Athens, Israel raids

Beirut airport, destroying 13 civilian planes. 1969 November

- Army Commander-in-Chief Emile Bustani and Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat sign an

agreement in Cairo which aims to control Palestinian guerrilla activities in

Lebanon. 1973 10

April - Israeli commandos raid Beirut and kill three close associates of Mr Arafat. The Lebanese government resigns the next day. 1975 13

April - Phalangist gunmen ambush a bus in the Ayn-al-Rummanah

district of Beirut, killing 27 of its mainly Palestinian passengers. The

Phalangists claim that guerrillas had previously attacked a church in the

same district. (These clashes are regarded as the start of the civil war). 1976 June

- Syrian troops enter Lebanon to restore peace but also to curb the

Palestinians, thousands of whom are killed in a siege of the Tel al-Zaatar

camp by Syrian-allied Christian militias in Beirut. 1976 October

- Following Arab summit meetings in Riyadh and Cairo, a ceasefire is arranged

and a predominantly Syrian Arab Deterrent Force (ADF) is established to

maintain it. Israel controls south 1978 March

- In reprisal for a Palestinian attack on its territory, Israel launches a

major invasion of southern Lebanon. The UN establishes the United Nations

Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) to oversee the Israeli withdrawal, restore

peace and help the government re-establish its authority. 1978 June

- Israel withdraws from all but a narrow border strip, which it hands over

not to UNIFIL but to a proxy mainly Christian militia - the South Lebanon

Army. Israel attacks 1982 June

- Following the attempted assassination of Shlomo Argov,

Israeli ambassador to Britain, by a Palestinian splinter group, Israel

launches a full-scale invasion of Lebanon. 1982 September

- Pro-Israeli president-elect Bachir Gemayel is assassinated. Israel occupies

West Beirut, where the Phalangist militia kills thousands of Palestinians in

the Sabra and Shatila camps. Lebanon Profile 1982 September

- Bachir's elder brother, Amine Gemayel, is elected president. 1982 September

- The first contingent of a mainly US, French and Italian peacekeeping force,

requested by Lebanon, arrives in Beirut. (1983 October

- A total of 241 US marines and 56 French paratroopers are killed in two bomb

explosions in Beirut, claimed by two Shia groups.) Buffer zone set up 1983 May

- Israel and Lebanon sign an agreement on Israeli withdrawal, ending

hostilities and establishing a security region in souther 1985 -

By 6 June most Israeli troops withdraw but some remain to support the mainly

Christian South Lebanon Army (SLA) led by Maj-Gen Antoine Lahoud which

operates in a "security zone" in southern Lebanon. 1985 16

June - A TWA plane lands in Beirut after having been hijacked on a flight

from Athens to Rome by two alleged members of Hezbollah demanding the release

of Shia prisoners in Israeli jails. 1987 21

May - Lebanon abrogates the 1969 Cairo agreement with the PLO as well as

officially cancelling the 17 May 1983 agreement with Israel. 1987 1

June - After Prime Minister Rashid Karami is killed when a bomb explodes in

his helicopter, Selim al-Hoss becomes acting prime minister. Two governments, one

country 1988 September

- When no candidate is elected to succeed him, outgoing President Amine

Gemayel appoints a six-member interim military government, composed of three

Christians and three Muslims, though the latter refuse to serve. Lebanon now

has two governments - one mainly Muslim in West Beirut, headed by El-Hoss,

the other, Christian, in East Beirut, led by the Maronite Commander-in-Chief

of the Army, Gen Michel Aoun. 1989 March

- Aoun declares a "war of liberation " against the Syrian presence

in Lebanon. 1989 October

- The National Assembly, meeting in Taif, Saudi Arabia, endorses a Charter of

National Reconciliation, which reduces the authority of the president by

transferring executive power to the cabinet. The National Assembly now has an

equal number of Christian and Muslim members instead of the previous six to

five ratio. 1989 November

- President Rene Moawad is assassinated shortly after his election and

succeeded by Elias Hrawi. The following day, Selim el-Hoss becomes prime minister and Gen Emile Lahoud

replaces Awn as Commander-in-Chief of the Army on 28 November. Civil war ends 1990 October

- The Syrian air force attacks the Presidential Palace at Baabda and Aoun

takes refuge in the French embassy. This date is regarded as the end of the

civil war. 1990 December

- Omar Karami heads a government of national reconciliation. 1991 -

The National Assembly orders the dissolution of all militias by 30 April but

Hezbollah is allowed to remain active and the South Lebanon Army (SLA)

refuses to disband. 1991 May

- A Treaty of Brotherhood, Cooperation and Coordination is signed in Damascus

by Lebanon and Syria and a Higher Council, co-chaired by their two

presidents, is established. 1991 July

- The Lebanese army defeats the PLO in Sidon so that it now confronts the

Israelis and the SLA north of the so-called "security zone". 1991 August

- The National Assembly grants an amnesty for all crimes committed during the

civil war, 1975-1990. Aoun receives a presidential pardon and is allowed to

leave for France. 1991 October

- Lebanon participates in the Middle East Peace Conference launched in

Madrid. 1992 February

- Sheikh Abbas al-Musawi, Secretary-General of Hezbollah, is killed when

Israeli helicopter gunships attack his motorcade on a road south-east of

Sidon. By 17 June all Western

hostages held by Shia groups have been released. 1992 October

- After elections in August and September (the first since 1972), Nabi Berri,

secretary-general of the Shia Amal organisation,

becomes speaker of the National Assembly. 1992 October

- Rafik Hariri, a rich businessman, born in Sidon but with Saudi Arabian

nationality, becomes prime minister, heading a cabinet of technocrats. 1993 July

- Israel attempts to end the threat from Hezbollah and the Popular Front for

the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC) in southern Lebanon by

launching "Operation Accountability", the heaviest attack since

1982. Israel bombs Beirut 1996 April

- "Operation Grapes of Wrath", in which the Israelis bomb Hezbollah

bases in southern Lebanon, the southern district of Beirut and the Bekaa. An

Israeli attack hits a UN base at Qana and results

in the death of over 100 displaced Lebanese civilians sheltering there. US negotiates a truce and

an "understanding" under which Hezbollah and Palestinian guerrillas

agree not to attack civilians in northern Israel, and which recognises Israel's right to self-defence

but also Hezbollah's right to resist the Israeli occupation of southern

Lebanon. Lebanon and Syria do not sign the "understanding" but the

Israel-Lebanon Monitoring Group (ILMG), with members from the US, France,

Israel, Lebanon and Syria, is set up to monitor the truce. 1998 April

- Israel's inner cabinet votes to accept UN Security Council Resolution 425

of 1978 if Lebanon guarantees the security of Israel's northern border. Both

Lebanon and Syria reject this condition. Lahoud becomes president 1998 November

- Army head Emile Lahoud is sworn in as president, succeeding President Hrawi. 1998 December

- Selim el-Hoss becomes prime minister, heading a

cabinet which includes no militia leaders and only two ministers from the

previous administration. 1999 June

- South Lebanon Army (SLA) completes its withdrawal from the Jazzin salient (north of the "security zone")

occupied since 1985. 2000 March

- Israeli cabinet votes for the unilateral withdrawal of Israeli troops from

southern Lebanon by July 2000. 2000 April

- Israel releases 13 Lebanese prisoners held without trial for more than 10

years but extends the detention of Hezbollah's Sheikh Abdel Karim Obeid and

Mustafa Dib al-Dirani. Israeli withdrawal 2000 May

- After the collapse of the SLA and the rapid advance of Hezbollah forces,

Israel withdraws its troops from southern Lebanon, more than six weeks before

its stated deadline of 7 July. |

25 May -

25 May declared an annual public holiday, called "Resistance and

Liberation Day". 2000 October

- Rafik Hariri takes office as prime minister for a second time. 2001 March

- Lebanon begins pumping water from a tributary of the River Jordan to supply

a southern border village, despite opposition from Israel. 2002 January

- Elie Hobeika, a key figure in the massacres of Palestinian refugees in

1982, dies in a blast shortly after disclosing that he held videotapes and

documents challenging Israel's account of the massacres. 2002 September

- Row with Israel over Lebanon's plan to divert water from a border river.

Israel says it cannot tolerate the diversion of the Wazzani,

which provides 10% of its drinking water, and threatens the use of military

force. 2003 August

- Car bomb in Beirut kills a member of Hezbollah. Hezbollah and a government

minister blame Israel for the blast. 2004 September

- UN Security Council resolution aimed at Syria demands that foreign troops

leave Lebanon. Syria dismisses the move. Parliament extends

President Lahoud's term by three years. Weeks of political deadlock end with

the unexpected departure of Rafik Hariri - who had at first opposed the

extension - as prime minister. Hariri assassinated 2005 February

- Rafik Hariri is killed by a car bomb in Beirut. The attack sparks

anti-Syrian rallies and the resignation of Prime Minister Omar Karami's

cabinet. Calls for Syria to withdraw its troops intensify. 2005 March

- Hundreds of thousands of Lebanese attend pro- and anti-Syrian rallies in

Beirut. Days after his

resignation, pro-Syrian former PM Omar Karami is asked by the president to

form a new government. 2005 April

- Mr Karami resigns as PM after failing to form a

government. He is succeeded by moderate pro-Syrian MP Najib Mikati. Syria says its forces

have left Lebanon, as demanded by the UN. 2005 June

- Prominent journalist Samir Qasir, a critic of Syrian influence, is killed

by a car bomb. Anti-Syrian alliance led

by Saad Hariri wins control of parliament following elections. New parliament

chooses Hariri ally, Fouad Siniora, as prime minister. George Hawi, anti-Syrian

former leader of Lebanese Communist Party, is killed by a car bomb. 2005 July

- Lebanese PM Siniora meets Syria's President Assad; both sides agree to

rebuild relations. 2005 September

- Four pro-Syrian generals are charged over the assassination of Rafik

Hariri. 2005 December

- Prominent anti-Syrian MP and journalist Gibran Tueni

is killed by a car bomb. 2006 February

- Denmark's embassy in Beirut is torched during a demonstration against

cartoons in a Danish paper satirising the Muslim

Prophet Muhammad. 2006 July

- Israel launches air and sea attacks on targets in Lebanon after Lebanon's

militant Hezbollah group seizes two Israeli soldiers. Civilian casualties are

high and the damage to civilian infrastructure wide-ranging. Thousands of

people are displaced. In August Israeli ground troops thrust into southern

Lebanon. 2006 August

- Truce between Israel and Hezbollah comes into effect on 14 August after 34

days of fighting and the deaths of around 1,000 Lebanese - mostly civilians -

and 159 Israelis, mainly soldiers. A UN peacekeeping force, expected to

consist of 15,000 foreign troops, begins to deploy along the southern border. 2006 September

- Lebanese government forces deploy along the Israeli border for the first

time in decades. Power struggles 2006 November

- Ministers from Hezbollah and the Amal movement resign shortly before the

cabinet approves draft UN plans for a tribunal to try suspects in the killing

of the former prime minister Hariri. Leading Christian

politician and government minister Pierre Gemayel is shot dead. 2006 December

- Thousands of opposition demonstrators in Beirut demand the resignation of

the government. 2007 January

- Hezbollah-led opposition steps up pressure on the government to resign by

calling general strike. 2007 March

- Tent town which sprang up in central Beirut as part of the opposition

sit-in to demand more say in government, remains in place 100 days after

start of protest. 2007 May-September

- Siege of the Palestinian refugee camp Nahr

al-Bared following clashes between Islamist militants and the military. More

than 300 people die and 40,000 residents flee before the army gains control

of the camp. 2007 May

- UN Security Council votes to set up a tribunal to try suspects in the

assassination of ex-premier Hariri. 2007 June

- Anti-Syrian MP Walid Eido is killed in a bomb attack in Beirut. 2007 September

- Anti-Syrian MP Antoine Ghanim is killed by a car bomb. Parliament adjourns the

session to elect a new president until 23 October, after a stay-away by the

opposition pro-Syrian bloc. Power vacuum 2007 November

- President Emile Lahoud steps down after parliament fails to elect his

successor. Prime Minister Fouad Siniora says his cabinet will assume powers

of presidency. 2007 December

- Car bomb kills Gen Francois al-Hajj, who had been tipped to become army

chief. 2008 January

- Bomb blast apparently aimed at a US diplomatic vehicle in Beirut kills

four. 2008 May

- At least 80 people are killed in clashes between Hezbollah and

pro-government factions, sparking fears of civil war. Parliament elects army

chief Michel Suleiman as president, ending six-month-long political deadlock.

Suleiman reappoints Fouad Siniora as prime minister, entrusting to him task

of forming new unity government. 2008 July

- Political leaders reach agreement on make-up of national unity government. Ties with Syria

established 2008 July

- President Suleiman meets Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Paris. They

agree to work towards establishing full diplomatic relations between their

countries. Israel frees five

Lebanese prisoners in exchange for the remains of two Israeli soldiers

captured by Hezbollah in July 2006. Hezbollah hails the swap as a

"victory for the resistance". 2008 October

- Lebanon establishes diplomatic relations with Syria for first time since

both countries gained independence in 1940s. 2009 March

- International court to try suspected killers of former Prime Minister

Hariri opens in Hague. Expected to ask Lebanon to hand over four pro-Syrian

generals held over February 2005 killing within weeks. 2009 April

- Former Syrian intelligence officer Mohammed Zuhair al-Siddiq arrested in

connection with killing of former PM Rafik Hariri. Four pro-Syrian Lebanese

generals held since 2005 over Hariri murder freed after UN court in Hague

rules that there is not enough evidence to convict them. 2009 May

- US Vice-President Joe Biden visits ahead of June parliamentary elections,

prompting accusations from Hezbollah that US is "meddling" in

Lebanese affairs. Lebanese officials say an army colonel has been arrested on

suspicion of spying for Israel. Unity government 2009 June

- The pro-Western March 14 alliance led by Saad Hariri wins 71 of 128 seats

in parliamentary elections while the rival March 8 alliance, led by

Hezbollah, secures 57. Saad Hariri is nominated as prime minister. 2009 July

- The Lebanese army says it broke up a cell of 10 al-Qaeda-linked Islamists

whom it accused of planning to attack troops and UN peacekeepers in the

south. 2009 November

- Saad Hariri succeeds in forming government of national unity, five months

after his bloc won majority of seats in parliament. 2009 December

- Lebanon's cabinet endorsed Hezbollah's right to keep its arsenal of

weapons. Prime Minister Saad

Hariri visits Damascus for talks with President Bashar Assad, describing the

talks as friendly, open and positive. 2010 April

- US warns of serious repercussions for Syria if reports that it supplied

Hezbollah with Scud missiles were true. PM Sa'ad Hariri earlier dismisses the

accusations against Syria. 2010 July

- Lebanon's most eminent Shia cleric, Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Hussein

Fadlallah, dies. Border tension 2010 August

- Lebanese and Israeli troops exchange fire along border; two Lebanese

soldiers, a senior Israeli officer and a journalist are killed. 2010 October

- Amid signs of heightened sectarian tension, Iranian President Mahmoud

Ahmadinejad pays controversial visit to Lebanon that culminates in rally held

at Hezbollah stronghold near Israeli border. Hezbollah leader Hassan

Nasrallah calls on Lebanese to boycott UN tribunal into 2005 killing of

former PM Rafik Hariri, saying the tribunal is in league with Israel. 2011 January

- Government collapses after ministers from Hezbollah and its political

allies resign. UN prosecutor issues

sealed indictment for murder of Rafik Hariri. Najib Mikati is appointed

prime-minister designate and is asked to form a new government. 2011 June

- After nearly five months of tortuous wrangling and horse-trading, Mr Mikati finally succeeds in forming a cabinet. The new

cabinet is dominated by Hezbollah and its allies, which are given 16 out of

30 seats. The UN's Special Tribunal

for Lebanon (STL) issues four arrest warrants over the murder of Rafik

Hariri. The accused are members of Hezbollah, which says it won't allow their

arrest. 2012 Summer

- Syrian conflict spills over into Lebanon's northern port of Tripoli in

deadly clashes between Sunni Muslims and Alawites. 2012 October

- Security chief Wissam al-Hassan is killed in a car bombing along with two

other people near the police headquarters in Beirut. Opposition blames the

attack on Syria, and protesters at the funeral try to storm government

buildings and demand the resignation of Prime Minister Najib Mikati. Police

fire warning shots and tear gas. |

1. For a thorough account of the earlier period, see Engin Deniz Akarli, The Long Peace: Ottoman Lebanon, 1861-1920

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

2. ‘Syria’ was in fact divided administratively into four smaller

states, primarily in order to aid colonial control by dividing the population

along ethno-religious lines. One of the classic works on the mandate period in

Syria is Philip S Khoury, Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab

Nationalism, 1920-1945, Princeton University Press, 1987.

3. For an account of the economic and social changes during the mandate,

see Elizabeth Thompson, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal

Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon (Columbia University Press),

2000, and Buheiry, Beirut’s Role in the Political

Economy of the French Mandate, 1919-39; Gates, The Merchant Republic of

Lebanon, chap. 2.

4. Hala Jaber, Hezbollah, 1997, 9.

5. For details see Graham E. Fuller and Rend Rahim Francke, The Arab

Shi’a: The Forgotten Muslims, 1999)

6. For more on the impact of the Second World War on French imperialism,

see Martin Thomas, The French Empire at War, 1940-45 (Manchester University

Press, 1998.

7. For Khoury’s term and the onset of independence, see Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon, chap. 7.

8. No official census was taken after 1932, so the exact demographic

weight of each group was largely determined by political consensus.

9. For details see Graham E. Fuller and Rend Rahim Francke, Arab Shi'a:

The Forgotten Muslims, 2001

10. Fuller and Francke, The Arab Shi’a, 46.

11. Fuller and Francke, The Arab Shi’a, 10.

12. For more on the social and economic crisis see, Salim Nasr, Backdrop

to Civil War: The Crisis of Lebanese Capitalism. MERIP Reports, No. 73 (Dec.,

1978), pp. 3-13

13.

http://www.c-r.org/sites/c-r.org/files/Accord24_ExMilitiaFighters.pdf

13. http://www.ghazi.de/civwar.html

14. John C. Rolland, Lebanon: Current Issues and Background, 2013, 144

For updates click homepage

here