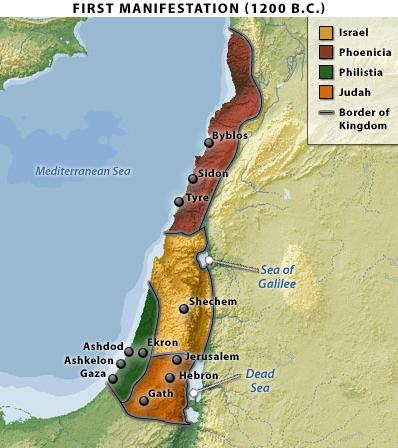

From a historical point of view one could say, that 'Israel' has

manifested itself three times in history. The first manifestation began with the

invasion led by Joshua and lasted through its division into two kingdoms, the

Babylonian conquest of the Kingdom of Judah and the deportation to Babylon

early in the sixth century B.C. The second manifestation began when Israel was

recreated in 540 B.C. by the Persians, who had defeated the Babylonians. The

nature of this second manifestation changed in the fourth century B.C., when

Greece overran the Persian Empire and Israel, and again in the first century

B.C., when the Romans conquered the region.

The second manifestation saw Israel as a small actor within the framework

of larger imperial powers, a situation that lasted until the destruction of the

Jewish vassal state by the Romans.

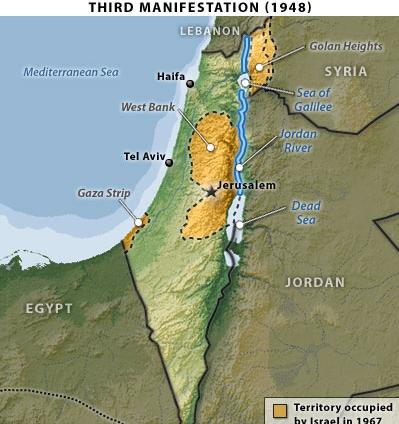

Israel’s third manifestation began in 1948, following (as in the other

cases) an ingathering of at least some of the Jews who had been dispersed after

conquests. Israel’s founding takes place in the context of the decline and fall

of the British Empire and must, at least in part, be understood as part of

British imperial history.

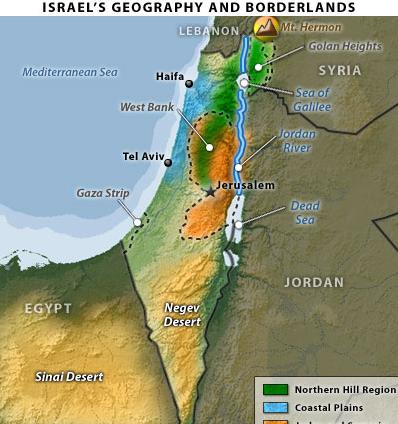

Israel’s reality today is this. It is a small country, yet must manage

threats arising far outside of its region. It can survive only if it maneuvers

with great powers commanding enormously greater resources. Israel cannot match

the resources and, therefore, it must be constantly clever. There are periods

when it is relatively safe because of great power alignments, but its normal

condition is one of global unease.

On the other hand the Arabs don’t really care about the Palestinians

other than for the destruction of Israel. For example Gaza is a nightmare into

which Palestinians (fleeing Israel) were forced by the Egyptians.

The idea for what where de facto Arab-Muslims to call

themselves 'Palestinians' came as a reaction to the Jewish

migration to what is now Israel after WWI. When World War I ended the rule

of the Ottoman Empire, which controlled the Middle East came to an end.

Shortly after the British took over in 1920 they moved the Hashemites to

an area in the northern part of the peninsula, on the eastern bank of the

Jordan River. Centered around the town of Amman, they named this protectorate

carved from Syria “Trans-Jordan,” as in “the other side of the Jordan River,”

since it lacked any other obvious identity. After the British withdrew in 1948,

Trans-Jordan became contemporary Jordan. The Hashemites also had been given

another kingdom, Iraq, in 1921, which they lost to a coup by Nasserist military

officers in 1958.

West of the Jordan River and south of Mount Hermon was a region that had

been an administrative district of Syria under the Ottomans. It had been called

“Philistia” for the most part, undoubtedly after the Philistines whose Goliath

had fought David thousands of years before. Names here have history. The term Filistine eventually came to be known as Palestine, a name

derived from ancient Greek — and that is what the British named the

region.

Bernard Avishai in The Tragedy of Zionism

(2002) made a good case for the fact that it was not Zionism that brought

majority of Jews to what is now Israel before the 1920’s, but more so

anti-Jewish American immigration policy that forced Jews fleeing first the

Russian pogroms and then the widespread anti-Semitism in Europe, away from

American shores.

Another erroneous claim assumes a close relation between the

Zionist movement, established in 1897 at a conference in Basle, Switzerland,

and the major states (that ended up supporting the establishment of a Jewish

state in the Middle East) of the time. None of the major powers either helped

create, funded or supported the goal of a Jewish state until after World

War II.

In fact at the end of WWII the British would intercept all Jews who were

trying to flee Germany or Europe to what is now Israel. Captured either on the

high seas or within sight of Palestine they were taken to Cyprus and detained

in camps surrounded by barbed wire and guards until early 1947 I believe. One

example history still remembers but probably only because a movie was made out

of it, was the ship Exodus with four thousand mostly former concentration

camp inmates that after WWII had ended received passage from France. The ship

arrived and was able to dock in the port of Haifa, but the British would not

let the passengers disembark, and insisted upon the ship returning to its

French port of origin. When the Jews refused to disembark in France, the

British government sent the ship back to Germany.

Winston Churchill, speaking in the House of Commons on 1 August 1946,

exclaimed that the idea that the Jewish problem could be helped by a

dumping of the Jews of Europe into Palestine is really too silly to consume our

time in the House this afternoon. (In: the Best of Winston Churchill's

Speeches, London: Pimlico, 2003, p. 426.)

Few historians furthermore have given attention to the Zionist

arguments which predated Labor Zionism. And focus instead on the changes in the

moral perceptions of Israelis since 1967, plus the diplomatic changes brought

on by the Israeli/Arab War with as a result the occupation of the West

Bank and Gaza. (1)

A Short History of Jerusalem.

The relationship

between the Jewish people and Jerusalem goes back to pre-Roman times. The

following shows the campaign by the Romans against Jerusalem, destroying its that time Temple. Any tourist walking under the “Arch

of Titus” in Rome completed in 81 CE, can see the following image:

More

recent archaeological excavations carried out near the Temple Mount,

uncovered a terraced street from the Herodian era, extended 600 meters to the

Temple. The excavators think the drainage canals under the street are those

mentioned by contemporary historian Josephus Flavius- who said the Romans

trapped the Jews who hid under the streets.

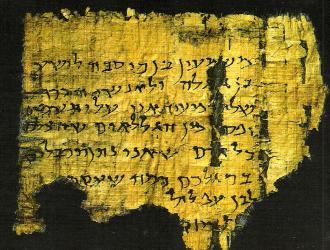

In the

following letter by Bar Kochba, written during

(a next) revolt against Rome in 132-135 CE, he seeks to recruit

"Galileans," which some scholars interpreted as Christians. Emperor

Hadrian however, feared the revolt could spark the hopes of enslaved peoples

across the Roman Empire. (G.W. Bowerstock, "A

Roman Perspective on the Bar Kochba War," in W.

S. Green, ed., Approaches to Ancient Judaism, 2, 1980).

In spite of popular

believe, on the other hand Jerusalem is not connected to any events in

Muhammad's life and is not mentioned in the Koran.

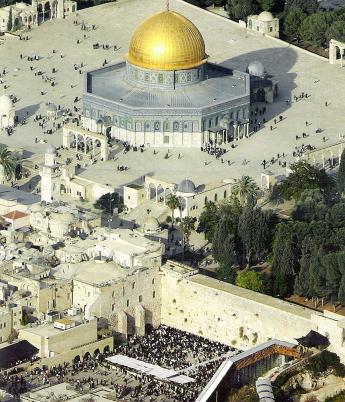

It was in the century

after Muhammad's death, that politics, prompted the Damascus-based Umayyad

dynasty, which controlled Jerusalem, to make this city sacred in Islam.

Embroiled in fierce competition with a dissident leader in Mecca, the Umayyad

rulers were seeking to diminish Arabia at Jerusalem's expense. They sponsored a

genre of literature praising the "virtues of Jerusalem" and

circulated re-invented accounts of the prophet's sayings or doings (called

hadiths) favorable to Jerusalem. In 688-91, they built the Dome of the Rock, on

top of the remains of the Jewish Temple. They also were the ones that

reinterpreted the Koran to make room for Jerusalem.

However, when the

Umayyad dynasty collapsed in 750, Jerusalem fell into near-obscurity. For the

next three and a half centuries, texts praising the city lost favor and the

construction of glorious buildings not only stopped, but existing ones fell

apart (the Dome over the rock collapsed in 1016).

Judaism to compare

this with the above has made Jerusalem a holy city over three thousand years

ago and through all that time Jews remained steadfast to it. Jews pray in its

direction, mention its name constantly in prayers, close the Passover service

with the wistful statement "Next year in Jerusalem," and recall the

city in the blessing at the end of each meal. The destruction of the Temple

looms very large in Jewish consciousness; remembrance takes such forms as a

special day of mourning, houses left partially unfinished, a woman's makeup or

jewelry left incomplete, and a glass smashed during the wedding ceremony. In

addition, Jerusalem has had a prominent historical role, is the only capital of

a Jewish state, and is the only city with a Jewish majority during the whole of

the past century. In the words of its current mayor, Jerusalem represents

"the purist expression of all that Jews prayed for, dreamed of, cried for,

and died for in the two thousand years since the destruction of the Second

Temple."

One comparison makes

this point most clearly: Jerusalem appears in the Jewish Bible 669 times and

Zion (which usually means Jerusalem, sometimes the Land of Israel) 154 times,

or 823 times in all. The Christian Bible mentions Jerusalem 154 times and Zion

7 times. In contrast Jerusalem or/and Zion appear not even once in the Qur'an.

So why does it now

loom so large for Muslims? Why does King Fahd of Saudi Arabia call on Muslim

states to protect "the holy city [that] belongs to all Muslims across the

world"? Why suddenly do Muslims all over the world find Jerusalem one of

their most pressing foreign policy issue?

Because of politics,

an historical survey shows that the stature of the city, and the emotions

surrounding it, inevitably rises for Muslims when Jerusalem has political

significance.

The inhabitants of

what now is called Palestine and Israel, at the start of the 20th

Cent. considered themselves part of the Ottoman dominated Syrian

provinces. Arab nationals from Nablus, Jerusalem and Jaffa considered themselves

Ottomans or Syrians.

A recent study

using archival material describes the radicalization of this Palestinian

movement, see

underneath here

The Jerusalem Problem

In order to inflame

Muslim opinion during the 1920’s, Arab nationalists under the leadership of

Hajj Amin al-Husseini circulated doctored photographs of a Jewish flag with the

Star of David flying over the Dome of the Rock. Hajj Amin al-Husseini also

instigated a move to change the paved area in front of the generally recognized

to be Jewish-Wailing (Western) Wall, which was transformed from a cul-de-sac

into an open thoroughfare. The British one could argue helped politicize the

issue by the decision to appoint Hajj Amin al-Husseini as grand mufti of

Jerusalem

The heart of the

Palestinian Arab argument at the time was that the Western Wall was

primarily a Muslim holy site. According to Muslim traditions they claimed,

it was where Muhammad tied his winged horse-, on whom he had miraculously flown

from Mecca to Jerusalem before ascending to the heavens from the Temple Mount

(see the wall below):

The International

Commission for the Wailing Wall, also known as the Shaw Commission, was

appointed by the British with League of Nations approval. It still indicated

that it preferred a voluntary solution to the controversy, but it ultimately

drafted a decision formally confirming Jewish rights of access to the Western

Wall. But, backing the British, it also accepted a highly restrictive

interpretation of what these rights entailed. For example, the commission ruled

that Jews could not bring benches or chairs to the Wall area, and an ark

containing Torah scrolls could only be brought on special holidays. This

reflected the commission's understanding of the status quo under the Ottoman

Empire. (Report of the Commission Appointed by His Majesty’s Government in the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and with the Approval of

the Council of the League of Nations, to Determine the Rights and Claims of

Moslems and Jews in Connection with the western or Tyailing

Tyall at Jerusalem , London: His Majesty's Stationery

Office, 1931).

The commission did

not contest the Muslim claim to ownership over the Wall and the pavement in

front of it, but it utterly rejected the notion that al-Buraq was tethered in

the area where the Jews prayed, suggesting that this location was further

south. Hence it concluded, "Under these circumstances the Commission does

not consider that the Pavement in front of the Wall can be regarded as a sacred

place from a Moslem point of view.” It traced the Jewish use of the site for

prayer back to the fourth century CE, adding for further corroboration the

accounts of the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela

from 1167, written before the area was declared waqf property. (Ibid.) These

results were totally unacceptable to the mufti and the Supreme Muslim Council,

who now rejected the legal competence of any international body except a

Shariah court to settle questions about Muslim holy sites. (Esco

Foundation for Palestine, Palestine: A Study of Jewish, Arab, and British

Policies, Volume Two (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1947, 614).

Husseini then sought

to further internationalize his struggle. The Supreme Muslim Council authorized

him to invite Arab and Muslim leaders to a World Islamic Conference in

Jerusalem slated for December 1931. When the conference opened the attendance

initially looked impressive-about 130 delegates from twenty-two countries.

Important states were absent, though. Turkey did not attend and even sought to

subvert the conference, concerned that it would become a forum for restoring

the caliphate and undermining the secular regime of Ataturk. The Saudi leader,

King Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, diplomatically explained that the invitation to the

Jerusalem conference had arrived too late. In all likelihood a Saudi decision

had been taken to boycott the whole event. (Y. Porath, The Palestinian Arab

National Movement: 1929-1939 From Riots to Rebellion, London, 1977, 10).

Their approach was

colored by their experience in organizing the Congress of the Islamic World in

Mecca back in 1926. That conference had ended acrimoniously, with its

resolution to meet annually in Mecca coming to naught. Five years later, Ibn

Saud was not going to lend his weight to a Jerusalem conference that might

succeed where the Mecca conference had failed. Clearly, Husseini had not

convinced international Muslim leaders that Jews were threatening Islamic holy

sites. In fact, the purpose of the whole event was not entirely clear. Husseini

had stressed to invitees that the conference would deal with the Buraq aI-Sharif. In his public call to the conference, however, Shawkat Ali said nothing about the Buraq aI-Sharif, but rather spoke more generally about how

Muslims might defend their civilization

Husseini's conference

was convened on December 6, 1931, which corresponded on the Islamic calendar to

the day that Muhammad ascended to the heavens from the Temple Mount . At the

opening of the conference, Husseini's supporters resorted to their tried and

true tactic of disseminating doctored photos, this time showing Jews with

machine guns attacking the Dome of the Rock. The use of this transparent

propaganda alienated many delegates, who held a protest meeting at the King

David Hotel presided over by Husseini's Palestinian rival, Ragheb

Bey al-Nashashibi, the Jerusalem mayor. Husseini's congress sought to establish

a permanent body that would convene every two years. The executive committee of

the congress was headed by Husseini, thus giving him a pan-Islamic title and

platform for the first time. The congress also announced the need to establish

an Islamic university in Jerusalem, which apparently was not looked on favorably

by the religious leadership at al-Azhar in Egypt . Adopting a resolution

proclaiming the sanctity of the Buraq al-Sharif, the congress rejected the

report of the "Wailing Wall Commission." Finally, it formally decided

to deny Jews access to the al-Aqsa Mosque, despite the fact that Jews had their

own religious reasons for staying away from the Temple Mount . Notably, during

these disputes over the Western Wall Husseini did not adopt the tactic later

embraced by Vasser Arafat of denying in total the

religious history of the Jews. For example, the Supreme Muslim Council, which

Husseini had headed since 1921, published an English-language book in 1924 for

visitors to the Temple Mount area titled A Brief Guide to al-Haram ai-Sharif

Jerusalem. The book's historical sketch of the site related that "the site

is one of the oldest in the world. Its sanctity dates from the earliest

(perhaps from pre-historic) times. Its identity with the site of Solomon's

Temple is beyond dispute." The 1930 edition remained unchanged despite the

1929 Western Wall riots. The Supreme Muslim Council did not engage in Temple

Denial, as Arafat's generation would decades later. Beginning in 1936,

Jerusalem 's position in Palestinian politics was greatly affected by what

became known as the Arab Revolt, although the revolt did not initially break

out in Jerusalem. Husseini and the Arab Higher Committee-another new body under

his leadership-declared a nationwide strike. In July 1937, the British finally

cracked down on the mufti, who hid out on the Temple Mount for three months.

(Meron Benvenisti, City of Stone: The Hidden History

of Jerusalem,Berkley, 1996, 79).

The area had become a

hiding place for weapons and explosives by Palestinian Arabs. In October 1937,

Husseini fled British Palestine, first heading for Lebanon, then Iraq and

finally Europe, where he met in Berlin with Adolf Hitler during November 1941

and became a close ally of the Nazi cause. (He would seek asylum after the war,

fearing he would be prosecuted as a war criminal.) In the meantime, back in

1937, the Palestinian strike metastasized into an armed revolt, with volunteers

arriving from neighboring countries. Other leaders arose to lead the

Palestinian Arabs' military struggle. A major side effect of the 1936 Arab

Revolt was that rural chieftains in British Mandatory Palestine provided much

of the revolt's leadership, Jerusalem, in fact, lost its pre-eminent place in

Palestinian politics. For example, of the 281 Arab officers involved, only ten

(or 3.5 percent) came from Jerusalem. (Michael C. Hudson, "The

Transformation of Jerusalem: 1917-1987 AD," in Kamil J. Asali, ed., Jerusalem in History: 3000 BC to the Present

Day, 1997, 256).

Amin al-Husseini next

became known for his meetings in Berlin with Adolf Hitler. After discussions

Grand Mufti and Hitler, the German Africa Corps landed in Libya in February

1941, the critical phase for extending the Holocaust to Palestine began.

On November 26, 1942,

al-Husseini, cast from Berlin a public radio speech in Arabic in what became a striking

example of the translation of Nazi propaganda into the idioms in the Arab world

even today.” Jews and capitalists have

pushed the United States to expand this war, in order to expand their influence

in new and wealthy areas.- America is the greatest agent of the Jews, and the

Jews are rulers in America.”

Martin Cüppers and Klaus-Michael Mallmann,

in their study of 2006 "Halbmond und Hakenkreuz,

on the basis of countless examples, reject the research opinion that has

prevailed up to now which assumes irreconcilable ideological differences

between Arab Nationalists and National Socialists. The National Socialists

planned mass murder also of the Jews in Palestine in 1942. Mallmann

and Cüppers conclude that the only thing that

prevented a "German-Arab mass crime" against the Jews was the defeat

of the Germans in North Africa.

It was noteworthy

that prior to the adoption of the UN General Assembly resolution in November

1947 calling for the partition of Palestine, the representatives of the

Palestinian Arabs did not make the issue of Jerusalem their primary focus. Jama

al- Husseini, the mufti's cousin, who presented the Palestinian Arab position

before the United Nations, still used pan-Arab motifs in making the case of the

Arab Higher Committee that he represented: "one consideration of

fundamental importance to the Arab world was that of racial homogeneity."

He explained that "the Arabs lived in a vast territory stretching from the

Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, spoke one language, had the same history,

tradition, and aspirations." He referred to the threat of an "alien

body" entering the Middle East region. (Document 4: "UN General

Assembly Resolution 181 on the Future Government of Palestine," Ruth Lapidoth and Moshe Hirsch, eds., The Jerusalem Question and

Its Resolution: Selected Documents, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1994, 13-14).

In fact even when Muslims

retook Jerusalem in 1948, they quickly lost interest in it. In spite of

'Abdallah being crowned as "King of Jerusalem", the Hashemites had

little affection for Jerusalem. In fact, the Hashemites made a concerted effort

to diminish the holy city's importance in favor of their capital, Amman.

Jerusalem had served as the British administrative capital, but now all

government offices there (save tourism) were shut down. The Jordanians also

closed some local institutions (e.g., the Arab Higher Committee) and moved

others to Amman (the treasury of the Palestinian waqf, or religious endowment).

Their effort

succeeded. Once again, Arab Jerusalem became an isolated provincial town, now even

less important than Nablus. The economy stagnated and many thousands left Arab

Jerusalem. While the population of Amman increased five-fold in the period

1948-67, Jerusalem's grew just 50 percent. Amman was chosen as the site of the

country's first university as well as of the royal family's many residences.

Perhaps most insulting of all, Jordanian radio broadcast the Friday prayers not

from al-Aqsa Mosque but from a mosque in Amman.

Nor was Jordan alone

in ignoring Jerusalem; the city virtually disappeared from the Arab diplomatic

map. No foreign Arab leader came to Jerusalem between 1948 and 1967, and even

King Hussein visited only rarely. King Faisal of Saudi Arabia often spoke after

1967 of yearning to pray in Jerusalem, yet he appears never to have bothered to

pray there when he had the chance. Perhaps most remarkable is that the

Palestinian Liberation Organization's founding document, the Palestinian

National Covenant of 1964, does not even once mention Jerusalem.

All this abruptly

changed after June 1967, when the Old City came under Israeli control. As in

the British period, Palestinians again made Jerusalem the centerpiece of their

political program. Pictures of the Dome of the Rock turned up everywhere, from

Yasir Arafat's office to the corner grocery.

The April 1949 Armistice Agreement

As a result of the

First Arab-Israeli War, Jerusalem was divided, with its Old City coming under

the occupation of the Arab Legion of the Hashemite Kingdom of ]ordan. Relations between Israel and Jordan over Jerusalem

were supposed to be governed by their April 3, 1949, Armistice Agreement.

According to Article VIII of the armistice, both sides undertook to guarantee

free access to Mt. Scopus as well as the resumption of the "normal

functioning" of its "cultural and humanitarian institutions."

The same article also assured "free access to the Holy Places and cultural

institutions and the use of the cemetery on the Mount of Olives." If

Article VIII had been implemented, Israelis would have been able to visit the

Old City of ]erusalem and pray at the Western Wall.

The Jordanians were to obtain road access to Bethlehem and the provision of

Israeli electricity to the Old City. To work out the modalities of these

principles, the same article called on both governments to appoint

representatives to a "Special Committee" that was supposed to

formulate detailed plans. True, there was a regular Israeli convoy to Mt.

Scopus, but the Special Committee was disbanded even before its meetings got

under way, so that no arrangements could be put in place for reopening Hebrew

University or the Hadassah Hospital . More significant, Israelis were denied

access to both the Western Wall and the Mount of Olives during the entire

period of Jordanian rule. Jordan further barred non-Israeli Jews from the

Western Wall, demanding that tourists present a certificate of baptism before a

visa would be granted. Formally, the Jordanians maintained that the scope of

the Special Committee needed to be broadened to include other holy sites inside

Israel such as those in Nazareth. (Tawfik al- Khalil, Jerusalem from 1917 to

1967, Amman: Economic Press, 90-92).

The true motivation

behind Jordanian policy in these years was revealed in a frank exchange on

February 23, 1951, between Jordanian prime minister Samir al-'Rifa'i and an Israeli envoy, Reuven Shiloah.

Al-Rifa'i disclosed why his country had no intention

of implementing its armistice obligations under Article VIII-Jordan simply had

nothing to gain from the armistice any longer. Jordan no longer needed access

to the Bethlehem road from Israel-the Jordanians had built another road

instead-and the Old City would no longer need Israeli electricity after Jordan

worked out a different source of electrical power. (Raphael Israeli, Jerusalem

Divided: The Armistice Regime 1947-1967, London, 2002, 58).

Noticing that the

British and U.S. ambassadors to Israel in 1954 were presenting their

credentials to the Israeli president in Jerusalem, one Palestinian writer

bemoaned that Israel had made Jerusalem into a capital while Jordan had reduced

it "from a position of preeminence to its Current place that does not rise

above rank of a village." (Kimberly Katz, Jordanian Jerusalem: Holy Places

and National Spaces, University Press of Florida, 2005, 85).

Christianity in

Jerusalem also suffered setbacks. Starting in 1953, the Jordanians decided that

Christian institutions would face restrictions in buying land in and around

Jerusalem. There were worldwide protests against the Jordanian actions, leading

the Jordanians to suspend the application of some of these provisions.

Nonetheless, according to one historical account, two years later the British

consul-general wrote a cable about an "anti-Christian tendency"

evident in Jordanian behavior. (Wasserstein, 193).

By the 1960s

Christian schools were told that they would have to close on Fridays instead of

Sundays, which had been their past practice. In this difficult environment, the

Christian population of Jerusalem declined from 25,000 in 1948 to 10,800 in

1967. (Address of Foreign Minister Abba Eban to the

Knesset, June 30, 1971. See John M. Oesterreicher,

"Jerusalem the Free," in Oesterreicher and

Sinai, 258)

It would be erroneous

to conclude however that during the period of its rule, Jordan essentially cut

itself off from Jerusalem; Jordan always sought to invest in the area of the

Temple Mount. Between 1952 and 1959, the Jordanians undertook a new restoration

project at the Dome of the Rock. The U.S. began to receive reports in 1960 that

Jordan planned to treat Jerusalem as a second capital. (Document 31, "Aide

Memoire Delivered by the United States Department of State to the Prime

Minister of Jordan Concerning the Intention of Jordan to Treat the City of

Jerusalem as Its Second Capital, 5 April 1960," in Lapidoth

and Hirsch, 160).

During the period of

Jordanian rule, another political body would come to influence the struggle for

Jerusalem : the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). It was founded in May

1964 by a conference of four, hundred delegates meeting at the Intercontinental

Hotel in Jordanian-controlled Jerusalem. Its first head, Ahmad Shukeiry, was a Palestinian who served as a Saudi Arabian

diplomat until he fell out with the Saudi leadership. The early PLO was

completely controlled by Egypt , which sponsored the proposal for its creation

at an Arab Summit meeting in order to reduce the relative responsibility of the

Arab states to resolve the Palestinian issue. The PLO covenant rejected Jewish

claims to Palestine and the validity of the League of Nations mandate. But it

did not specifically single out Palestinian claims to Jerusalem, which are not

even mentioned in the covenant-either in its original version promulgated in

1964 or in its 1968 rendition. (Wasserstein noted that there was no mention of Jerusalem

either in its ten-point political statement issued in Cairo on June 8,1974).

The early PLO had good reasons to leave Jerusalem out of its founding charter.

It did not want to antagonize its Jordanian hosts.

Enter Arafat:

For a short period of

four years in the mid-1930s, Arafat's widowed father sent him from Cairo to

Jerusalem to live with his mother's family. He was a child volunteer to one of

the assistants to the mufti, who became for Arafat a figure to be emulated. In

order to sustain the legend that he promoted about his past, Arafat would argue

that he fought in the First Arab-Israeli War under Abdul Qader

al-Husseini, who was both the mufti's cousin and one of the main Palestinian

commanders who died in the battle for Jerusalem. Arafat did fight in the 1948

war, but not with the Palestinians as he maintained. Instead, he was recruited

into the Egyptian tmits that were organized by the

Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo. (M. Shemesh, The Palestinian Entity 1959-1974:

Arab Politics and the PLO, London, 1996).

Even after Arafat's

takeover of the PLO, certain aspects of the organization's unique approach to

the Jerusalem question only became evident many years later. Arafat's real

political constituency that sustained him in power over the years was located

in the Palestinian refugee camps, first on the East Bank in Jordan, and then in

Lebanon. The Palestinian elites in East Jerusalem were not part of that

constituency and even presented a potential alternative leadership, at times,

to Arafat's organization, which was based far away in Lebanon and later in

Tunisia. Due to the PLO's refusal for several decades formally to renounce

terrorism or meet any of the minimal pre-conditions that the U.S. set for a

diplomatic dialogue, the East Jerusalem leadership would be able to meet U.S.

secretaries of state, while Arafat could not even see a U.S. ambassador.

Because Arafat had a

different political constituency, he was willing to agree to tactical

concessions in Jerusalem that were unacceptable to the local leadership. In

fact, looking ahead a number of decades, one of the reason that Israeli prime

minister Yitzhak Rabin was willing to pursue a secret negotiating track with the

PLO in Oslo-which eventually led to the signing of the Declaration of

Principles in 1993 on the White House lawn-was precisely because the PLO was

willing to exclude Jerusalem from any interim self-governing arrangements for

the Palestinians.

Indeed, while

Jerusalem played a central role in Yasser Arafat's rhetoric, he was willing to

set the Holy City aside, when pressed in negotiations, in the years that

followed.

By then of course,

the 1967 Six-Day War had revolutionized the situation of Jerusalem by bringing

about its reunification after nineteen years. Moreover, the specific conditions

out of which the conflict erupted created new legal rights and diplomatic terms

of reference that would replace the armistice agreements of 1949; for the

armistice agreements had patently failed, and something new was needed in their

stead. But the immediate causes of the war were related to developments on

other fronts. Military tensions along the Israeli-Syrian front rose steadily

from April 1967, provoking the Soviet Union deliberately to mislead Egypt into

believing that an Israeli strike on Syria was imminent.

As a result, the

Egyptian regime under President Gamal Abd aI-Nasser

took three critical steps that led inevitably to war. First, Nasser massed

80,000 troops in Egyptian Sinai along Israel 's southern Negev border. Next, to

give credibility to his threat, the Egyptian president demanded that the UN

Emergency Force that had been deployed for a decade along that sensitive border

zone withdraw-and UN secretary-general U Thant complied. Finally, Nasser

announced a naval blockade of Israel's southern port of Eilat. All shipping

between the port and the Red Sea and Indian Ocean was thus threatened by

artillery positions Egypt had emplaced adjacent to the narrow Straits ofTiran, near the tip of the Sinai peninsula. The Egyptian

president's military buildup had taken on a momentum of its own. He announced

his intentions on May 26, 1967: "The battle will be a general one and our

basic objective will be to destroy Israel." (Document 39, "Nasser's

Speech to Arab Trade Unionists," May 26,1967, Walter Laqueur

and Barry Rubin, eds., The Israeli-Arab Reader: A Documentary History of the

Middle East Conflict, New York: Penguin Books, 1984, 176).

But

Internationalization had already patently failed back in 1948; the UN hadn't

lifted a finger to break the siege of Jerusalem, leading Prime Minister

Ben-Gurion to declare in 1949 that the elements in Resolution 181 that related

to Jerusalem were "null and void." Now the EU was resurrecting a

superannuated UN General Assembly resolution that had been utterly rejected by

the Arab side in 1947 and had been abandoned afterwards by the Israelis after

they had waged a bitter war, with no international help, in Jerusalem's

defense. In any case, it had not been a legally binding international

agreement, but only a failed recommendation of the UN. The newly articulated EU

position only radicalized the Palestinians.

The official Palestinian

Authority newspaper al-Ayyam quoted on March 14,

1999, the conclusion of the leading Palestinian negotiator, Abu Ala': "The

[EU's] letter asserts that Jerusalem in both its parts-the Western and the

Eastern-is a land under occupation." It should be stressed that Abu Ala'

was thought by most Israelis to be pragmatic; he was the senior PLO official in

the Oslo back channel that led to the Oslo Agreement. Yet even his position had

hardened. Just over one year before Camp David, Arafat emerged from a meeting

with UN secretary-general Kofi Annan and spoke to reporters in Arabic about

Resolution 181. On March 25, his representative to the UN, Nasser al-Kidwa, then wrote a letter to Annan that was released as a

UN document in which he argued that the old partition boundaries from

Resolution 181 were what the international community had accepted. This

argument not only could be used to refute Israel 's claims to East Jerusalem,

but could egually be applied to West Jerusalem as

well. Meir Ben-Dov, Historical Atlas of

Jerusalem, New York: 2002, 214).

In fact Yasser Abd Rabbo, the Palestinian Authority minister of information,

confessed on a television program broadcast on November 17, 2000 on the

Qatar-based al-Jazeera network that there was "a

consensus among Palestinians that the direct goal is to reach the establishment

of an independent Palestinian state in the June 4, 1967, borders, with

Jerusalem as its capital, [but] regarding to the future after that, it is best

to leave the issue aside and not to discuss it."

Thus despite the

unprecedented concessions offered by Barak regarding Jerusalem, especially in

comparison with every preceding Israeli prime minister since 1967, the PLO did

not offer any corresponding readiness to compromise on territorial matters.

Arafat in essence insisted on receiving 100 percent of the West Bank, including

East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. He was only willing to concede land in

these territories if he received equivalent compensation via a land swap from

unpopulated territories inside of pre-1967 Israel like the arid Halutza area of the Negev. This in spite of the fact that

Resolution 242 from November 1967, which had served until Camp David as the

basis of Israeli - Palestinian agreements, did not articulate any need for a

land swap.

In fact Faisal

al-Husseini was far more revealing about the PLO's ultimate intentions during

the Oslo years. He compared Arafat's use of the Oslo peace process to a Trojan

horse that allowed the PLO to get the Israelis to open "their fortified

gates and let it inside their walls." The real strategic goal of the PLO,

he explained, had been a Palestine "from the [Jordan] River to the

[Mediterranean] Sea," and not a mini-state in the West Bank. (Donald

Little, "Jerusalem under the Ayyubids and the Mamluks: 1187-1516 AD,180).

Salim Za'anun, the chairman of the Palestine National Council,

stated in an official PA newspaper that the PLO covenant calling for Israel's

destruction had never changed and hence remained in force. To give these words

added authority, they were written up in the official Palestinian Authority

newspaper al-Hayat al-Jadida on January 1, 2001.

Black smoke came out

of Bethlehem's Manger Square, next to the Church of the Nativity, where on

April 2, 2002, a joint Hamas- Fatah Tanzim force of thirteen ('terrorists')

held the clergy as hostages for thirty-nine days:

In fact also

according to shi'ite echatology

according to the President of Iran Ahmadinejad, the destruction of Israel is

one of the key global developments that will trigger the appearance of the

Mahdi the 12th Imam of Meshad. In his first UN

General Assembly address, Ahmadinejad closed with a prayer that the Mahdi's

arrival be quickened: "Oh mighty Lord, I pray to you to hasten the

emergence of your last repository, the promised one." Dr. Bilal Na'im

assistant to the head of the Executive Council of Hizballah, discussing the

details of how the Mahdi is supposed to appear before the world, writes that

initially the Mahdi reveals himself in Mecca "and he will lean on the Ka'abah and view the arrival of his supporters from around

the world."

From Mecca the Mahdi

next moves to Karbala in Iraq. But his most important destination, in Na'im's

description, is clearly Jerusalem. It is in Jerusalem from where the launching

of the Mahdi's world conquest is declared. He explains, "The liberation of

Jerusalem is the preface for liberating the world and establishing the state of

justice and values on earth." (Search for Common Ground in the Middle

East, Program Update 2006).

As I explained at the

start of this website, there is a common misperception that preoccupation with

the coming of the Mahdi occurred only in the world of Shiism; but in fact,

Sunni Islam has generated a number of figures who claimed to be the Mahdi,

including the famous Mahdi of Sudan who fought General Gordon and the British

in the 1880s, and most recently Muhammad al-Qahtani, who with his

brother-in-law, Juhaiman al- Utaibi

took over the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979.

Even those who

downplay the influence of Islamic apocalyptic literature on the public at large

admit that it has a strong following among Islamic radicals.

Hamas is the

Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, a radical Sunni organization that

gave birth to many jihadist groups. Without forfeiting its ties to militant

Sunni networks Khaled Mashaal (left), the Damascus-based Hamas leader, meets

with Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (right) in Tehran on February 20,

2006:

During the years of

Oslo, Jordan lost much of its influence over the administration of Islamic

affairs on the Temple Mount to the Palestinian Authority, but it has been

seeking to recover it as of late. (Jerusalem Post, October 11, 2006, Edgar

Lefkovits, "Jordan Plans New Temple Mt.

Minaret," Jerusalem Post, October 11, 2006). In fact one could wonder if

Arab states like Saudi Arabia would do better, by supporting the moderate

role of Jordan in these administrative issues today. No state should have an

interest in radical Islamic sermons in the al-Aqsa Mosque calling for the

overthrow of various UN recognized countries that include in fact, Arab

regimes.

The Question of an Independent Palestinian State

Palestinian

nationalism’s first enemy is Israel, but if Israel ceased to exist, the

question of an independent Palestinian state would not be settled. All of the

countries bordering such a state would have serious claims on its lands, not to

mention a profound distrust of Palestinian intentions. The end of Israel thus

would not guarantee a Palestinian state. One of the remarkable things about

Israel’s Operation Cast Lead in Gaza was that no Arab state moved quickly to

take aggressive steps on the Gazans’ behalf. Apart from ritual condemnation,

weeks into the offensive no Arab state had done anything significant. This was

not accidental: The Arab states do not view the creation of a Palestinian state

as being in their interests. They do view the destruction of Israel as being in

their interests, but since they do not expect that to come about anytime soon,

it is in their interest to reach some sort of understanding with the Israelis

while keeping the Palestinians contained.

The emergence of a

Palestinian state in the context of an Israeli state also is not something the

Arab regimes see as in their interest, and this is not a new phenomenon. They

have never simply acknowledged Palestinian rights beyond the destruction of

Israel. In theory, they have backed the Palestinian cause, but in practice they

have ranged from indifferent to hostile toward it. Indeed, the major power that

is now attempting to act on behalf of the Palestinians is Iran, a non-Arab

state whose involvement is regarded by the Arab regimes as one more reason to

distrust the Palestinians.

Therefore, while one could say that Palestinian nationalism was born in battle, it

was not only born in the conflict with Israel: Palestinian nationalism also was

formed in conflict with the Arab world, which has both sustained the

Palestinians and abandoned them. Even when the Arab states have gone to war

with Israel, as in 1973, they have fought for their own national interests, and

for the destruction of Israel, but not for the creation of a Palestinian state.

And when the Palestinians were in battle against the Israelis, the Arab

regimes’ responses ranged from indifferent to hostile.

The Palestinians are

trapped in regional geopolitics. They also are trapped in their own particular

geography. First, and most obviously, their territory is divided into two

widely separated states: the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Second, these two

places are very different from each other. Gaza is a nightmare into which

Palestinians fleeing Israel were forced by the Egyptians. It is a social and

economic trap. The West Bank is less unbearable, but regardless of what happens

to Jewish settlements, it is trapped between two enemies, Israel and Jordan.

Economically, it can exist only in dependency on its more dynamic neighboring

economy, which means Israel.

Gaza has the military

advantage of being dense and urbanized. It can be defended. But it is an

economic catastrophe, and given its demographics, the only way out of its

condition is to export workers to Israel. To a lesser extent, the same is true

for the West Bank. And the Palestinians have been exporting workers for

generations. They have immigrated to countries in the region and around the

world. Any peace agreement with Israel would increase the exportation of labor

locally, with Palestinian labor moving into the Israeli market. Therefore, the

paradox is that while the current situation allows a degree of autonomy amid

social, economic and military catastrophe, a settlement would dramatically

undermine Palestinian autonomy by creating Palestinian dependence on Israel.

The only solution for

the Palestinians to this conundrum is the destruction of Israel. But they lack

the ability to destroy Israel. The destruction of Israel represents a

far-fetched scenario, but were it to happen, it would necessitate that other

nations hostile to Israel, both bordering the Jewish state and elsewhere in the

region, play a major role. And if they did play this role, there is nothing in

their history, ideology or position that indicates they would find the creation

of a Palestinian state in their interests. Each would have very different ideas

of what to do in the event of Israel’s destruction.

Therefore, the

Palestinians are trapped four ways. First, they are trapped by the Israelis.

Second, they are trapped by the Arab regimes. Third, they are trapped by

geography, which makes any settlement a preface to dependency. Finally, they

are trapped in the reality in which they exist, which rotates from the

minimally bearable to the unbearable. Their choices are to give up autonomy and

nationalism in favor of economic dependency, or retain autonomy and nationalism

expressed through the only means they have — wars that they can at best

survive, but can never win.

The present division

between Gaza and the West Bank had its origins in the British mandate.

Palestine was partitioned between Jews and Arabs. In the wake of the 1948 War,

Arabs lost control of what was Israel; the borders that emerged from this war

and lasted until 1967 are still recognized as Israel’s international boundary.

The area called the West Bank was part of Jordan. The area called Gaza was

effectively under Egyptian control. Numbers of Arabs remained in Israel as

Israeli citizens, and played only a marginal role in Palestinian affairs

thereafter.

During the 1967

Arab-Israeli war, Israel occupied both Gaza and the West Bank, taking direct

military and administrative control of both regions. The political apparatus of

the Palestinians, organized around the PLO, an umbrella organization of diverse

Palestinian groups, operated outside these areas, first in Jordan, then in

Lebanon after 1970, and then in Tunisia after the 1982 invasion of Lebanon by

Israel. The PLO and its constituent parts maintained control of groups

resisting Israeli occupation in these two areas.

The idea of an

independent Palestinian state, since 1967, has been geographically focused on

these two areas. The concept has been that, following mutual recognition

between Israel and the Palestinians, Palestine would be established as a nation-state

based in Gaza and the West Bank. The question of the status of Jerusalem was

always a vital symbolic issue for both sides, but it did not fundamentally

affect the geopolitical reality.

Gaza and the West

Bank are physically separated. Any axis would require that Israel permit land

or air transit between them. This is obviously an inherently unstable

situation, although not an impossible one. A negative example would be Pakistan

during the 1947-1971 period, with its eastern and western wings separated by

India. This situation ultimately led to the 1971 separation of these two

territories into two states, Pakistan and Bangladesh. On the other hand, Alaska

is separate from the rest of the United States, which has not been a hindrance.

The difference is obvious. Pakistan and Bangladesh were separated by India, a

powerful and hostile state. Alaska and the rest of the United States were

separated by Canada, a much weaker and less hostile state. Following this

analogy, the situation between Israel and the hypothetical Palestine resembles

the Indo-Pakistani equation far more than it does the U.S.-Canadian equation.

The separation

between the two Palestinian regions imposes an inevitable regionalism on the

Palestinian state. Gaza and the West Bank are very different places. Gaza is

about 25 miles long and no more than 7.5 miles at its greatest width, with a

total area of about 146 square miles. According to 2008 figures, more than 1.5

million Palestinians live there, giving it a population density of about 11,060

per square mile, roughly that of a city. Gaza is, in fact, better thought of as

a city than a region. And like a city, its primary economic activity should be

commerce or manufacturing, but neither is possible given the active hostility

of Israel and Egypt. The West Bank, on the other hand, has a population density

of a little over 600 people per square mile, many living in discrete urban

areas distributed through rural areas.

In other words, the

West Bank and Gaza are entirely different universes with completely different

dynamics. Gaza is a compact city incapable of supporting itself in its current

circumstances and overwhelmingly dependent on outside aid; the West Bank has a

much higher degree of self-sufficiency, even in its current situation. Under

the best of circumstances, Gaza will be entirely dependent on external economic

relations. In the worst of circumstances, it will be entirely dependent on

outside aid. The West Bank would be neither. Were Gaza physically part of the

West Bank, it would be the latter’s largest city, making Palestine a more

complex nation-state. As it is, the dynamic of the two regions is entirely

different.

Gaza’s situation is

one of pure dependency amid hostility. It has much less to lose than the West

Bank and far less room for maneuver. It also must tend toward a more uniform

response to events. Where the West Bank did not uniformly participate in the

intifada, towns like Hebron were hotbeds of conflict while Jericho remained

relatively peaceful, the sheer compactness of Gaza forces everyone into the

same cauldron. And just as Gaza has no room for maneuver, neither do

individuals. That leaves little nuance in Gaza compared to the West Bank, and

compels a more radical approach than is generated in the West Bank.

If a Palestinian

state were created, it is not clear that the dynamics of Gaza, the city-state,

and the West Bank, more of a nation-state, would be compatible. Under the best

of circumstances, Gaza could not survive at its current size without a rapid

economic evolution that would generate revenue from trade, banking and other

activities common in successful Mediterranean cities. But these cities have

either much smaller populations or much larger areas supported by surrounding

territory. It is not clear how Gaza could get from where it is to where it

would need to be to attain viability.

Therefore, one of the

immediate consequences of independence would be a massive outflow of Gazans to

the West Bank. The economic conditions of the West Bank are better, but a massive

inflow of hundreds of thousands of Gazans, for whom anything is better than

what they had in Gaza, would buckle the West Bank economy. Tensions currently

visible between the West Bank under Fatah and Gaza under Hamas would intensify.

The West Bank could not absorb the population flow from Gaza, but the Gazans

could not remain in Gaza except in virtually total dependence on foreign aid.

The only conceivable

solution to the economic issue would be for Palestinians to seek work en masse in more dynamic economies. This would mean either

emigration or entering the work force in Egypt, Jordan, Syria or Israel. Egypt

has its own serious economic troubles, and Syria and Jordan are both too small

to solve this problem, and that is completely apart from the political issues

that would arise after such immigration. Therefore, the only economy that could

employ surplus Palestinian labor is Israel’s.

Security concerns apart,

while the Israeli economy might be able to metabolize this labor, it would turn

an independent Palestinian state into an Israeli economic dependency. The

ability of the Israelis to control labor flows has always been one means for

controlling Palestinian behavior. To move even more deeply into this

relationship would mean an effective annulment of Palestinian independence. The

degree to which Palestine would depend on Israeli labor markets would turn

Palestine into an extension of the Israeli economy. And the driver of this will

not be the West Bank, which might be able to create a viable economy over time,

but Gaza, which cannot.

From this economic

analysis flows the logic of Gaza’s Hamas. Accepting a Palestinian state along

lines even approximating the 1948 partition, regardless of the status of

Jerusalem, would not result in an independent Palestinian state in anything but

name. Particularly for Gaza, it would solve nothing. Thus, the Palestinian

desire to destroy Israel flows not only from ideology and/or religion, but from

a rational analysis of what independence within the current geographical

architecture would mean: a divided nation with profoundly different interests,

one part utterly incapable of self-sufficiency, the other part potentially capable

of it, but only if it jettisons responsibility for Gaza.

It follows that

support for a two-state solution will be found most strongly in the West Bank

and not at all in Gaza. But in truth, the two-state solution is not a solution

to Palestinian desires for a state, since that state would be independent in

name only. At the same time, the destruction of Israel is an impossibility so

long as Israel is strong and other Arab states are hostile to Palestinians.

Palestine cannot

survive in a two-state solution. It therefore must seek a more radical outcome,

the elimination of Israel, that it cannot possibly achieve by itself. The

Palestinian state is thus an entity that has not fulfilled any of its

geopolitical imperatives and which does not have a direct line to achieve them.

What an independent Palestinian state would need in order to survive is:

· The recreation of

the state of hostilities that existed prior to Camp David between Egypt and

Israel. Until Egypt is strong and hostile to Israel, there is no hope for the

Palestinians.

· The overthrow of

the Hashemite government of Jordan, and the movement of troops hostile to

Israel to the Jordan River line.

· A major global

power prepared to underwrite the military capabilities of Egypt and those of whatever

eastern power moves into Jordan (Iraq, Iran, Turkey or a coalition of the

foregoing).

· A shift in the

correlation of forces between Israel and its immediate neighbors, which

ultimately would result in the collapse of the Israeli state.

Note that what the

Palestinians require is in direct opposition to the interests of Egypt and

Jordan, and to those of much of the rest of the Arab world, which would not

welcome Iran or Turkey deploying forces in their heartland. It would also

require a global shift that would create a global power able to challenge the

United States and motivated to arm the new regimes. In any scenario, however,

the success of Palestinian statehood remains utterly dependent upon outside

events somehow working to the Palestinians’ advantage.

The Palestinians have

always been a threat to other Arab states because the means for achieving their

national aspiration require significant risk-taking by other states. Without

that appetite for risk, the Palestinians are stranded. Therefore, Palestinian

policy always has been to try to manipulate the policies of other Arab states,

or failing that, to undermine and replace those states. This divergence of

interest between the Palestinians and existing Arab states always has been the

Achilles’ heel of Palestinian nationalism. The Palestinians must defeat Israel

to have a state, and to achieve that they must have other Arab states willing

to undertake the primary burden of defeating Israel. This has not been in the

interests of other Arab states, and therefore the Palestinians have

persistently worked against them, as we see again in the case of Egypt.

Paradoxically, while

the ultimate enemy of Palestine is Israel, the immediate enemy is always other

Arab countries. For there to be a Palestine, there must be a sea change not

only in the region, but in the global power configuration and in Israel’s

strategic strength. The Palestinians can neither live with a two-state

solution, nor achieve the destruction of Israel.

(1) While

political Zionism came later, the Jewish writer Nathan Birnbaum for the

first time used the word `Zionism' in 1892. While anti-Semitism was common in

the whole of Europe and America, in 1881 the deadly anti-Jewish pogroms had

started to spread in Russia. From April till the end of that year, attacked by

mobs; about 100,000 Jews were left without means of gaining a livelihood. In

Minsk, fully a fifth of the city-1,600 buildings-was razed. Deaths numbered in

the hundreds, and the pogromists seemed particularly bent on abusing Jewish

women. One Yiddish song of the day included the haunting words: "Brides

taken from their grooms, children from their mothers: Shout, children, loud and

clear ... you can wake your father up, as if he were asleep for real."

Then in May 1882,

Minister of the Interior Nikolai Pavlovich Ignatiev

promulgated the May Laws. Once in the cities, the laws decreed, Jews could not

return to the countryside, and those who remained in villages-perhaps two

fifths of the total Jewish population-could expect little protection from the

Czar's provincial governors. Jews could expect harassment from the police and,

indeed, could be expelled to the cities by summary verdicts of rural courts

made up of half-literate muzhiks.

For the early

Zionists, democratic values were embedded in a number of prior questions, many

of them complex and charged with emotion. Zionists asked themselves if they

should choose Palestine or some other country, if they should start collective

farms or promote private enterprise. Another question was even more

fundamental: Should immigration be organized en

masse, by a sovereign Zionist "corporation," though any such method

of settling the Jewish national home was bound to produce a mix of European

languages there? Or should priority be given to supporting small groups of

cultural pioneers who were devoted to evolving modern Hebrew, however

gradually? Should Zionism wait for support from the imperial powers or go it

alone in small vanguard groups?

In this climate, Jews

began to fear that those whom the state could not assimilate would have to

disappear. An apocryphal story began to circulate that the Russian leaders had

already arrived at a formula that would doom them: one third by assimilation,

one third by expulsion, one third by murder.

A latecomer who was

to become known as the founder of the Zionist movement, Austrian Theodore

Herzl while studying Roman law at the University of Vienna, joined

the Burschenschaft Albia, a strongly nationalist

dueling fraternity. In 1883, when that group participated in an anti-Semitic

ceremony to commemorate Wagner's death, Herzl protested and was forced to

withdraw. But maybe Herzl had not intended to make a stand for the sake of the

Jews so much as to honor civility itself.

Then shortly after

Herzl in 1892 moved to France he was shocked when he saw insults being hurled

at French Jews and Jewish shops being attacked. As the provocations reached a

peak, several Jewish officers in the French Army answered those affronts in

duels. This all impressed Herzl enormously. And in 1893, his solution to the

Jewish question was the mass conversion of Jewish children to Christianity.

He toyed with the

idea of contacting the Pope and inviting him to preside over such a ceremony at

Vienna's St. Stephen's Cathedral; Herzl felt that honor demanded that he remain

Jewish, but the children, at least, would be saved.

In 1895 then, Herzl

witnessed the trial of Captain Alfred Dreyfus. And it is in the wake of

this, that "in a flash," or so he wrote, the idea of a Jewish state

came to him and he began frantically to jot down some ideas outlining his plan.

In May 1895, he requested an interview with Baron Maurice de Hirsch, who was

then funding the settlement of Jews in Argentina. But Hirsch was unreceptive

both to Herzl's proposals and to him. So Herzl decided to compose a series of

appeals to Dr. Moritz Güdemann, the Chief Rabbi

of Vienna, who gave him some encouragement. Thus Herzl proceeded with an

address to Edmond de Rothschild (the source of countless conspiracy theories

including in the USA today). And Herzl became the promoter of the so

called "Uganda" plan, a proposal for an African settlement, something

he held on to till the end of his life.

Thus during Zionism's

formative period, there were two major efforts to provide answers:

"political" Zionism and "cultural' Zionism. The dominant

trend, which developed mainly in Eastern Europe in response to political

Zionism, was cultural Zionism.

But confusion of the

mystical Jerusalem with the iconic one was precisely what traditional Judaism,

and Herzl’s Zionism, for that matter, were trying to avoid. But already one

year after Herzl’s death , the victory of cultural Zionists at the

Seventh Zionist Congress ensured that the fate of the Zionist cause would

next be determined by Jewish settlers in Palestine.

For Cultural Zionism

initially Hebrew and Jewish culture such as language, arts identity and religion,

however had been important rather then the potential

establishment of a state. They, in effect, saw Zionism as a solution to the

problems of Judaism and they were associated with the thinking of the writer

Asher Ginsberg (1856-1927). The second grouping, the political Zionists, argued

that the need for territory was the most important requirement of the Zionist

movement. Indeed, Herzl's pragmatic reaction to the proposals for the Ugandan

option was a clear illustration of the aim of the political Zionists. But as

the Zionist movement as a whole grew, more and more people also started to

emigrate to Palestine.

Yet a myth

surrounding the arrival of the various waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine

during this time was the question of their motives for coming in the first

place. The majority of the immigrants who came to Palestine did not do so for

Zionist reasons. Rather, they came for a variety of reasons that involved both

persecution in their country of origin and a lack of third country option. An

increasingly important factor after the United States closed its doors to

Jewish immigration at the end of the 19th century.

Many who came to

Palestine found life there to be too harsh and left. Emigration has been a

constant problem for the Zionist movement, both in Palestine and subsequently

in Israel. In both the Yishuv and the subsequent state of Israel, there is

clear linkage between immigration and security. In short, as much of the land

as possible had to be settled in order to control it.

In these early days

immigrants, most of whom came from Eastern European urban backgrounds,

struggled with having to make the land fertile. One of the dilemmas of the

early Zionist movement thus also became, who should farm the land?

First the view was that local Arab labor was both better equipped to

undertake this arduous task as much as it was also cheap. Whereby later

immigrants took the view that if a state for the Jews should be built it should

be by using Jewish labor. Eventually, the second group carried the day, but the

debate about using Arab or foreign labor never really went away.

In Eastern Europe,

Zionism remained a rather small movement, particularly when compared with

socialist Yiddishist groupings like the Allgemeiner Yiddisher Arbeiterbund-the "Bund"-which had been founded in

1897, the same year as the World Zionist Organization. Zionists also found

themselves in competition with Jewish activists drawn to a non-sectarian

Marxism.

However the

settlement activities in Palestine represented the practical approach to

Zionism, and this combined with political Zionism to form what was termed

`synthetic Zionism', which became closely associated with Chaim Weizman (1874-1952). Born in Russia, Weizman

played a central role in the development of the Zionist movement and was to

become Israel's first president. In 1904, Weizman

emigrated from Russia to Britain, where he lobbied for the Zionist cause and

played an influential role in winning some degree of British recognition for a

Jewish homeland in Palestine. Along with David Ben-Gurion, Weizman

became one of the central figures of the pre-state Zionist movement, serving as

President of the World Zionist Organisation during

1921-31 and 1935-46.

The cultural Zionists

succeeded in defining the goals which the Labor Zionist parties would

eventually implement. The first trend in Zionism, political Zionism, appealed

mainly to Western European intellectuals and contributed little in the way of

an ideology to the people who built up the first settlements. Political Zionist

prejudices were absorbed into Zionist myth as the early setlers

moved inexorably toward self-determination during the 1930’s. Only after they

were thought-rightly or wrongly-to anticipate the bitter lessons of World War

II did they put cultural Zionism in eclipse.

Especially the

Holocaust had two effects on the Zionist leadership and on the subsequent state

of Israel. The lack of an alternative host country made Jewish immigration to

Palestine all the more important. During the Second World War anti-Jewish

violence also had escalated to a degree where plans were put in place by the

Palestinian PLO in co-operation with the Nazi’s to exterminate murder all Jews

there. For a review of a recent book on this particular subject see here:

As a reaction also

Jewish military forces began to be organized and in 1946 when the full extent

of the Holocaust started to be known, violence broke out when the British

decided to force surviving Jews, to refugee camps in Cyprus. All Jews who were

trying to flee Germany or Europe, be it intercepted on the high seas or within

sight of Palestine were taken to Cyprus and detained in camps surrounded by

barbed wire and guards. Later made into a movie was the ship Exodus with four

thousand mostly former concentration camp inmates that had received passage via

France. The ship arrived and was able to dock in the port of Haifa, but the

British would not let the passengers disembark, and insisted upon the ship

returning to its French port of origin. When the Jews refused to disembark in

France, the British government sent the ship back to Germany.

Winston Churchill,

speaking in the House of Commons on 1 August 1946, exclaimed that the idea that

the Jewish problem could be helped by a vast dumping of the Jews of Europe

into Palestine is really too silly to consume our time in the House this

afternoon. (In: the Best of Winston Churchill's Speeches, London: Pimlico,

2003, p. 426.)

But while the world

was horrified by the Holocaust, most Western governments did little to increase

Jewish settlement to their respective countries. The realization that nothing

was too horrible to happen, the shattering of the myth that these things just

don't happen in a modern civilized world. This also affected Israeli

foreign policy-making and Israeli national identity later on. Second, the

development of the notion that the Jews must always be prepared to protect

themselves - they could not rely upon others to do this for them. They had

perished as a result of the failure of other party’s to defend them. And

explains why the notion of self-sufficiency in defense became a

cornerstone of Israeli defense doctrine, and played a role in the decision at

the start of the 1970s to develop a military industrial complex in Israel that

would arm the Israeli military.

For

updates click homepage here