Dueling claims from the military and the militants muddied the world's

understanding of an event that angered Western leaders, raised world oil prices

and complicated the international military operation in

neighboring Mali.

Today’s Algerian rescue operation at an eastern energy facility

apparently meant to demonstrate that Algiers would defend its national security

regardless of foreign nationals' safety or international opinion. This runs

counter to the Western convention that safeguarding the lives of hostages

during kidnapping situations is the paramount objective. The operation shows

that Algeria will cooperate with the West but not at the expense of its own

imperatives. According to media reports, as few as six and as

many as 35 hostages died in the raid.

Initial reports said that the militants took 41 foreigners and several

hundred Algerians hostage, but those figures seem to be significantly lower

than the actual number of hostages. Algeria's official news service, Algerie

Presse Service, is now reporting that 132 foreigners and at least 600 Algerians

were taken hostage. Algerie Presse Service is also reporting that the Algerian

army rescued approximately 575 Algerian hostages and about 70 of the foreign

hostages. Other local sources are reporting that 18 militants out of a now

estimated 30 have been killed thus far.

In many countries, any operation that results in civilian casualties is

deemed a failure. But this operation will not be as unpopular in Algeria. Thus

Algiers is operating with different constraints and interests that could

prioritize the quick resolution to the situation over the absolute safety of

the hostages.

The operation is also meant to convey to the West that Algerian

cooperation in Mali is not subject to negotiation on national security or

regime stability. Algeria reluctantly conceded to French support in the

military intervention. So far, Algeria has opened its airspace to French

fighter aircraft flying to Mali and staging locations in the Sahel.

What is particularly worrisome is the fact that hostages are still

unaccounted for despite the bloody engagement between the Algerian security

forces and the kidnappers. The kidnappers are now fully aware that Algerian

security forces are hunting them down and are willing to use deadly force. This

elevates the risk to the hostages, who could be killed in crossfire or by the

kidnappers if the militants decide to eliminate the hostages before being

neutralized. In addition, it does not appear that the militants secured any

ransoms -- likely a large incentive for the kidnappings -- and this could make

the kidnappers more likely to kill the hostages.

Algerian forces are currently searching the large compound for the

hostages and the remaining kidnappers and fanning out across the desert to

locate any kidnappers attempting to escape. There are also reports that the

remaining kidnappers and their hostages have moved toward the industrial part

of the complex, where they have threatened to blow up the complex if the

Algerians make another assault.

The Jihadist Threat in Western

and North Africa

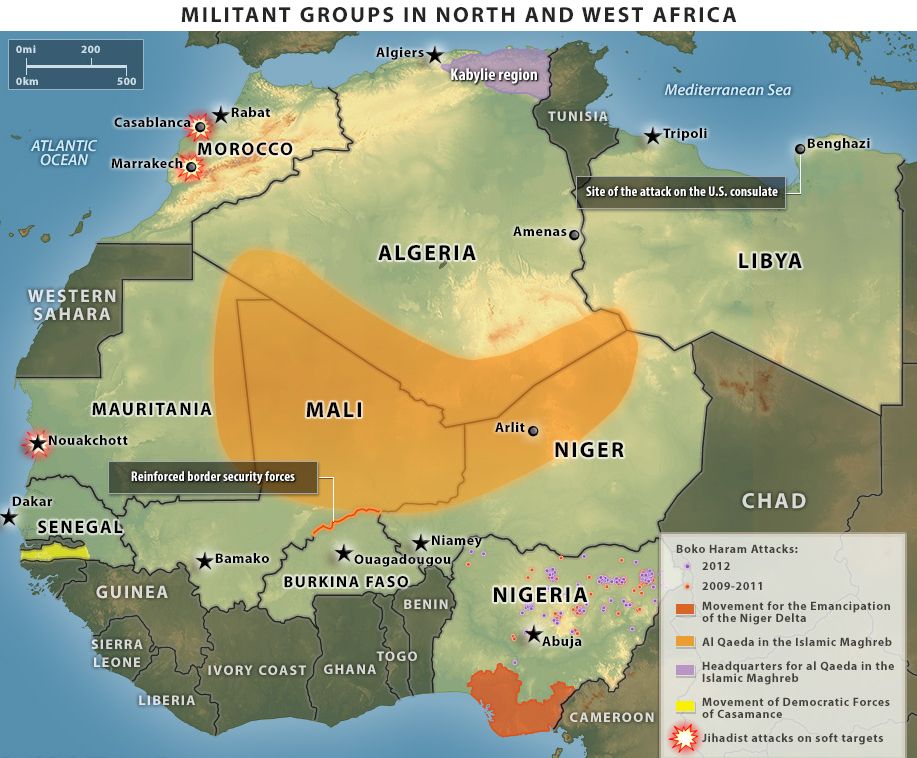

Several factors have allowed al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb to find

havens in the region, enabling jihadist fighters to launch geopolitically

disruptive attacks in western and North Africa. These factors include the

existence of an indigenous conflict, a local, largely Tuareg population to

blend into, the jihadists' Algerian nationality and the presence of economic

infrastructure manned by foreign personnel.

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb has operated in two principal theaters:

the Kabylie Mountains of northeastern Algeria and the

Sahel region with a focus on northern Mali. In 2013, the group supplanted the

latest iteration of an indigenous Tuareg rebellion and asserted control over a

vast swath of northern Mali. It has since become the governing authority in

cities including Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal, though French and African military

intervention is degrading and disrupting this control.

Belmokhtar was last seen in December 2012 in Gao. He reportedly went

underground in Mali in late 2012 after a disagreement with his superiors in al

Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, in which he had been a unit commander. The split

may have arisen over differing views of how much the franchise should align its

ideology with that of the al Qaeda core. It might also have occurred because of

Belmokhtar's frustrated leadership ambitions, which he sought to promote by

splitting off and launching his Algerian attack. Disagreements over revenue

sharing from kidnapping operations may also have contributed to the split.

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, and specifically Belmokhtar's

organization, has carried out attacks in the Sahel region outside northern

Mali. Its attacks typically have involved swift strikes or hostage taking, with

none resulting in even short-term occupation of territory. It has kidnapped

foreign nationals in Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Algeria, transporting foreign

hostages to the Kidal region of Mali, where they are held to extract ransom

payments from the West or for use in prisoner exchanges. Al Qaeda in the

Islamic Maghreb still holds seven foreign hostages from attacks that took place

before the Algerian assault.

Mali

To tap into the Tuareg rebellion in Mali, al Qaeda in the Islamic

Maghreb had some of its members marry into the Tuareg, an ethnic group that

straddles the Algerian-Malian border. This gave the jihadists the ability to

blend into local populations and to hide its movements, and even to have

indigenous rebels do their bidding. Gaining Tuareg rebels as spokesmen and

soldiers alongside some black Africans also helped the jihadists achieve their

military objectives.

In return, the jihadists greatly strengthened two indigenous militant

groups, Ansar Dine and the Movement for Jihad and Unity in West Africa, and a

secular armed group, the National Movement for the Liberation of the Azawad, in

their struggle against Bamako and against each other. But once northern Mali

was conquered, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb revealed its presence to the

outside world and pushed the Tuaregs aside. None of the Malian militant groups

challenged or confronted al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb for control of

northern Mali.

Algeria

In contrast to Mali, visibility is an asset for al Qaeda in the Islamic

Maghreb in Algeria, where it can more plausibly present itself as homegrown.

The group and its predecessors have more than 20 years of experience conducting

an insurgency against the Algerian state, and al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

can easily impersonate Algerian security officials, something the Algerian

prime minister said they did to infiltrate the remote energy facility at In Amenas. The relative abundance of foreigners helping operate

economically significant, difficult-to-defend energy facilities in the desolate

south of Algeria, a region of porous borders, also makes Algeria attractive to

jihadists seeking targets to attack.

Mauritania and Niger

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb has carried out limited operations in

the Mauritanian capital of Nouakchott and in the Nigerien capital of Niamey. A

cell of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb is suspected of leading the

unsuccessful assassination attempt against Elhadj Ag Gamou,

a senior Malian army commander likely being recruited to form part of the

intervention force being prepared to oust jihadists from northern Mali. Gamou said three men on motorcycles attacked him as he left

a Nigerien army camp, where he was probably attending a planning meeting with

the Malian and Nigerien presidents.

In 2008 the jihadist group carried out a small-arms attack against the

Israeli Embassy in Nouakchott. In 2009, it killed an American teacher working

in Mauritania in what appears to have been a botched kidnapping attempt. In

2010, the group kidnapped five French workers at the Areva uranium mine near Arlit in northwestern Niger. The jihadists transported the

hostages to Mali's Kidal region, eventually releasing them in February 2011

reportedly in exchange for a ransom of almost $17 million. Jihadists in Niger

also have attacked military checkpoints and have employed mines or improvised

explosive devices against convoys in order to loot their supplies.

But al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb faces limitations to its operations

in Mauritania and Niger. While the jihadists can conduct limited operations

there, often using Tuaregs as cover, neither country has an ongoing rebellion

that the jihadists can take over as they did in Mali. It also must work harder

to pass its Algerian personnel off as Nigerien or Mauritanian civilians. There

are not large pockets of Western citizens found outside the capitals of Niger

or Mauritania, with the exception of uranium mine sites near Arlit in the Agadez region of northern Niger. Moreover, the

authorities in Mauritania and Niger have reinforced their security measures to

defend against the jihadist group.

Niger plans to send ground forces into Mali as part of the African

intervention force, and Chadian troops have deployed into Niger likely in

preparation for the upcoming intervention in Mali's Gao region. Niamey also has

sought to reduce the threat of a Tuareg rebellion by using economic and

political patronage funded through uranium mining taxation receipts, giving the

Nigerien Tuaregs a stake in government decision-making.

Mauritania has not contributed forces to the African intervention in

Mali, but it has reinforced security on its border with Mali. Its army also

receives Western military training and other assistance. In February,

Mauritania will host the U.S.-organized Exercise Flintlock, which will bring

together military personnel from the United States and Canada as well as

countries in Western Europe and Africa to improve counterterrorism cooperation

and coordination in the Sahel. But while Mauritania can increase its security

posture with Western assistance, it cannot fully secure its territory against

al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb infiltration or prevent jihadists from finding

sympathizers in Nouakchott. Nouakchott must therefore carefully balance the

need to defend against al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb with the caution

necessary to avoid drawing the jihadists' hostility.

Security in Niamey and Nouakchott probably has been reinforced, with

checkpoints long before one reaches the capitals. Meanwhile, foreign nationals

probably are subject to strict security procedures to minimize their risk of

being attacked. For its part, Areva probably reinforced its security and likely

receives dedicated intelligence and protective security from the French

military mission leading the intervention in Mali. These do not totally

eliminate the possibility of an attack, but they do make it harder for Algerian

or Tuareg gunmen to move supplies or conduct limited attacks before fleeing to

their safe zones in northern Mali (or possibly Libya).

Morocco

Like Libya, the North African country of Morocco faces threats from

jihadist groups such as the al Qaeda-affiliated Ansar al-Sharia. Though the

groups are not extensions of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, like the latter,

they wish to attack the Moroccan government. They also have maintained links

with al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in a bid to acquire expertise, weapons,

training and funding.

Local jihadist cells like Ansar al-Sharia may gain inspiration from what

al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb affiliates achieved in Algeria, but various

factors in Morocco will limit the effectiveness of terrorist operations. For

example, there are significant tensions between the Algerian and Moroccan

governments, and this makes it hard for Algerians, who have distinct accents

from Moroccans, to move around Morocco without attracting attention. Rabat also

has a pervasive security apparatus that has proven very effective at

dismantling jihadist cells before they evolve into much of a threat. A bomb

attack such as the one carried out in Marrakech in April 2011 remains a

possibility, but it would be difficult to replicate given the heavy government

surveillance in Morocco.

The potential cells in Morocco also need training and weaponry; assault

weapons are very difficult to acquire there. Moreover, Morocco's borders to a

large extent are locked down. In southern Morocco, a militarized berm located

well inside the border creates a free-fire zone within Moroccan territory,

helping prevent illegal crossings. And Morocco's border with Algeria is closed

to normal traffic.

Libya

Libya is the weakest state in the Maghreb and Sahel regions. Central

government authorities are hard-pressed to control even Tripoli and lack a

meaningful presence in the rest of the country. The country hosts a diverse

array of jihadists from across the region -- for example, Belmokhtar reportedly

was seen in Sirte and Benghazi and possibly even Tripoli recruiting fighters --

along with multiple subnational, ethnically aligned armed groups all competing

to defend turf, loot weapons and sell themselves to the highest bidder.

On top of this is an almost total absence of border controls and of

intelligence on jihadists, along with potentially lucrative resources in the

form of tremendous crude oil reserves -- though these currently are unusable,

at least in lawless eastern Libya -- and no national command authority. All of

this makes Libya especially vulnerable to becoming a jihadist sanctuary. Al

Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb will indeed look to Libya as a haven should their

remaining strongholds, such as in the Kidal Mountains of the Gao region in

Mali, fall to foreign intervention forces.

Nigeria

Nigeria faces its own ongoing Islamist rebellion, in its case led by the

Boko Haram group. Boko Haram and al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb have shown a

small degree of cooperation, with some Boko Haram personnel allegedly seen in

northern Mali at the height of jihadist occupation there and with some

Nigerians -- among a host of Africans -- involved in the Algerian attack.

But no geopolitically significant economic infrastructure exists in

northern Nigeria, especially in northeastern Nigeria where Boko Haram is

concentrated, that would raise the profile of any al Qaeda operation. And while

a small number of foreigners do reside in northern Nigeria, none are active in

internationally significant activities on par with Algerian energy production

or even Nigerien uranium production. A small number of foreigners have been

kidnapped in northern Nigeria, but that they have not been transported to

Mali's Kidal region suggests that al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb has little

tactical connection to Boko Haram.

Southern Nigeria, home to the country's oil production in the Niger

Delta, does face a low-level militancy campaign. But the region's ethnic Ijaw

population is a staunch defender of the present Nigerian administration led by

President Goodluck Jonathan, himself an Ijaw. It would be extremely difficult

for Sahel jihadists to infiltrate into the Niger Delta given ethnic

differences. Moreover, the Ijaw want to control the region themselves, and

would not take kindly to foreigners undermining their leverage over the natural

resource that supports their political prominence.

Senegal

A low-level rebellion exists in Senegal's southern Casamance region, but

there never has been an al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb contingent active in

Senegal. Moreover, there is no significant indigenous Tuareg population for the

jihadists to blend into. Dakar and other urban locations in Senegal do host a

large number of foreigners who could be held for ransom, but the country lacks

internationally significant economic resources, such as oil and natural gas.

Burkina Faso

The government of Burkina Faso supports the French-backed West African

intervention in Mali, and Ouagadougou is readying troops for the African force.

Burkina Faso reportedly has reinforced its northern border security, an area

just opposite Mali's militant-held Gao region. The ethnic Tuareg population of

Burkina Faso is small, no reports that jihadists have infiltrated it have

emerged and there is no rebellion in Burkina Faso. While there are some mining

activities in the country that require the involvement of Western employees --

creating a reservoir of potential hostages -- such a strike would have to be a

very quick operation given that al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb would be

operating in an otherwise disadvantageous environment.

Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s group, which carried out the kidnapping operation,

reportedly has claimed that operations against the Algerian government will

continue.

For updates click homepage

here