After the Algerian military yesterday's final assault on terrorists

holding hostages at a gas complex, the hostage crisis is over. The man who

orchestrated the attack, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, is a veteran

jihadist with a long-standing relationship with al Qaeda in the Islamic

Maghreb, other jihadist networks in North Africa and al Qaeda branches

elsewhere in the Islamic world.

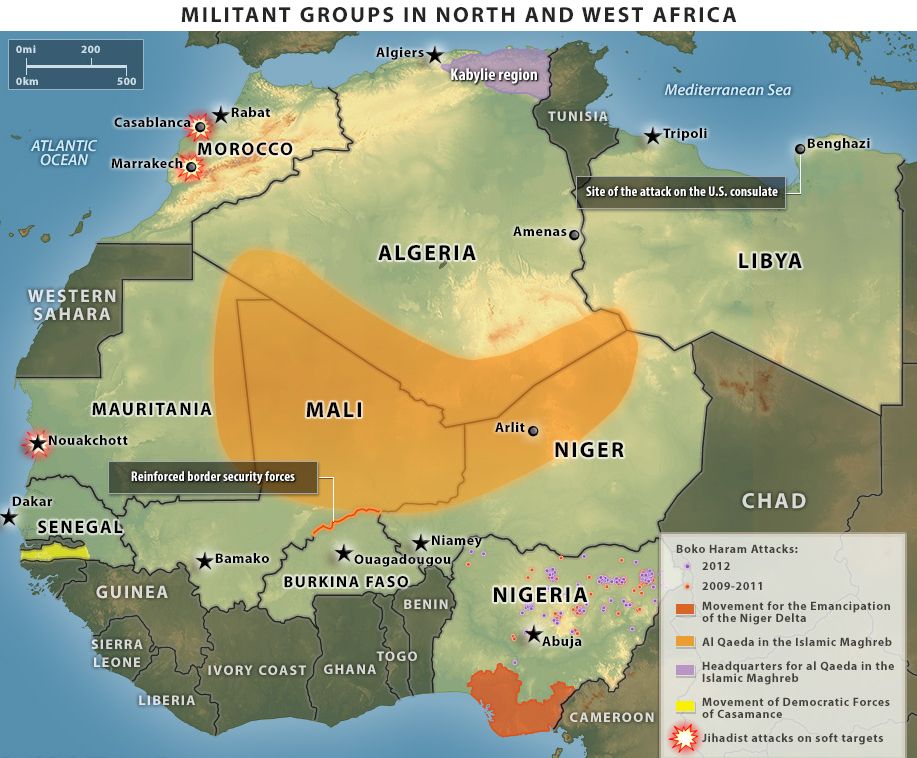

Al Qaeda's North African branch is a loose network of jihadist groups

that differ in their goals but will collaborate on certain operations.

Belmokhtar often had tenuous relationships with other leaders within al Qaeda

in the Islamic Maghreb, particularly Abdelmalek Droukdel (also known as Abu

Musab Abd al-Wadoud), the al Qaeda branch's overall

commander and leader in northern Algeria. Belmokhtar's faction of al Qaeda in

the Islamic Maghreb enjoyed a great deal of autonomy until al-Wadoud's close ally Yahya Abu al-Hammam was appointed as

emir of the al Qaeda sub-branch for the Sahel region in October 2012 and

Abdelhamid Abou Zeid, Belmokhtar's rival, was named his deputy. Around the same

time, Belmokhtar -- who had been passed over twice for the position of emir of

the Sahel -- was demoted to leader of the Mulathameen

Brigade, or the "Masked Ones," during the al Qaeda branch's reshuffle

of its southern leadership structure. Al-Wadoud and

other emirs had lost control of Belmokhtar and

factions aligned with him and sought to regain power by demoting Belmokhtar.

This -- along with a dispute over the allocation of the revenues from hostage

ransoms, usually negotiated by Belmokhtar -- created a split between Belmokhtar

and al Qaeda, though it is unclear whether he was forced out or he quit.

In December 2012, Belmokhtar established a new jihadist group called the

"Those

Who Sign in Blood" which he intended to use to expand operations into

countries throughout the Sahel. He probably will use the same means to finance

his group that he and his colleagues in al Qaeda used -- most notably, arms

trafficking, drug and tobacco smuggling and kidnapping Westerners for large

ransoms. Belmokhtar said he would recruit militants from across North Africa

and the Sahel, though previously he typically recruited from the western

portion of the region (primarily Mauritania, Mali and Algeria). The nationalities

of the foot soldiers in the attack on the Algerian natural gas facility --

including Tunisians, Libyans and Egyptians -- indicate that Belmokhtar has the

ability and finances to recruit foot soldiers from across North Africa.

However, the commanders in the operation were Algerian, Nigerian and

Mauritanian, indicating that Belmokhtar has not yet recruited commanders from

eastern North Africa.

The lack of security in nearby Libya and the presence of al Qaeda

militants in Algeria and Mali

make the region a breeding ground for militancy, so Belmokhtar likely will be

able to find many recruits.

Moreover, Belmokhtar appears capable of tapping into regional militant

networks and using them to his advantage. For instance, several of the

Egyptians who participated in the Jan. 16 kidnapping also allegedly took part

in the Sept. 11, 2012, attack on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, according to

investigations into the Algeria operation.

The Loss of Key Militant

Commanders

When Belmokhtar established "Those Who Sign in Blood," several

of his key commanders and lieutenants from his al Qaeda brigade went with him.

Three of them, Abdul Rahman al-Nigeri, Tahar Ben Cheneb and Abu al-Baraa al-Jazairi,

were either killed or captured during the 16 Jan. operation.

These men had been the orchestrators and commanders that Belmokhtar often sent

to carry out complex attacks.

Prior to the Jan. 16 attack in Algeria, Belmokhtar's three most

successful operations were his involvement in the kidnapping of 32 European

tourists in central Algeria in 2003, an assault by more than 100 men on a

Mauritanian military barracks in Lemgheiti in 2005

and the kidnapping of seven Europeans working at a uranium mine in Niger in

2010. Many of those involved in the high-profile 2003 kidnappings are now in

jail. Al-Nigeri and Belmokhtar commanded the raid on Lemgheiti in 2005, and Cheneb,

al-Nigeri and al-Baraa al-Jazairi

took part in the assault in Niger. Their deaths or capture are a large blow to

Belmokhtar's operational capability, but it is possible that there are lower-profile, albeit important, commanders that could be

used in future operations.

Future Attacks

The loss of key leaders during the Algeria operation could mean that

Belmokhtar and his brigade will need more time before they can carry out

another attack involving so many foreign hostages. Moreover, other large-scale

kidnappings at energy facilities, particularly in Algeria, are unlikely in the

short term because of the heightened security presence that can be expected at

many of these sites -- especially high-profile, government-owned facilities.

Although the most recent operation was in Algeria, it is not the only

country at risk for militant attacks. Algeria, Mali, Mauritania,

Niger, Morocco, Libya and Nigeria share external conditions conducive to such

attacks.

First, porous borders, which are characteristic of many countries in the

Sahel, are ideal for allowing the flow of regional and transnational jihadists.

Lack of border security becomes even more of an issue when neighboring

countries are unstable. For instance, the Algeria attack took place along the

vast and largely unsecured border with Libya. Second, a weak security

environment, often in conjunction with a weak central government, poses obvious

risks. In places like Mali, Libya and Mauritania, a weak central government

unable to control and secure its territory makes the country susceptible to a

militant presence.

Third, a country's terrain -- especially vast deserts, mountains and

largely uninhabited areas -- can make it ideal for militant corridors,

trafficking routes or camps. Finally, a population that is sympathetic to jihad

ideology makes it difficult for governments to identify and eradicate militant

elements.

Moreover, Belmokhtar's group is not the only militant organization that

kidnaps foreigners in the Sahel; such incidents typically occur three to five

times each year. Sometimes other militant groups sell their hostages to

Belmokhtar, who buys them with the intention of negotiating large ransoms.

Although it may be several months before Belmokhtar and his brigade

carry out another operation on the same scale as the Algeria attack, militancy

in the region will continue along with kidnapping operations. Militants in the

region could also conduct operations against potentially vulnerable targets

such clinics, schools, nongovernmental organizations and tourist sites, making

the region's security environment even more tenuous.

For updates click homepage

here