Greece (no stranger to economic crises such as

the current one) has not had many good days in 2010, but yesterday was

a particularly bad day. First, Europe’s statistical office (Eurostat) revised

up the Greek 2009 budget deficit, which placed Athens’ accounting shenanigans

in the spotlight again. The bottom line is that the situation is even worse

than previously thought, and the budget deficit may very well be adjusted up as

more Greek accounting malfeasance comes to light. Following the announcement,

credit rating agency Moody’ s dropped Greece’s credit rating one notch,

immediately prompting a rise in Greek government bond yields, thus increasing

Athens’ borrowing costs.

The Greek economic

imbroglio that has engulfed the European Union in its most serious economic and

political crisis ever look like it is building to a climax, with the likely

conclusion on May 10 when the eurozone leaders meet in Brussels.

The point is that the

financial writing is now on the proverbial wall; some form of default is simply

unavoidable. What is also of importance is that it is only a matter of time

when Credit rating agency’s will also downgrade Spain and Portugal.

The Greek default

therefore is no longer an isolated problem, but a problem that threatens to

aggravate an already weakened European banking sector. One of the most

misunderstood facts of the international financial world is that even at the

peak of the U.S. subprime crisis, in the dark hours when American hedge funds

seemed to be snapping like matchsticks, Europe’s banks were in

even worse shape.

As the Americans

stabilized, so did their banks. But Europe never cleaned house, and now a Greek

tsunami is poised to wash over the whole mess.

The current fear is

that the eurozone’s indecision and foot-dragging on providing Athens with a

financial aid package has so undermined investors’ confidence that the crisis

is no longer just about Greece. Markets are already in the process of testing

Portugal. Though the country’s economy is about three-fourths the size of

Greece’s, it too is a member of the group of profligate spenders in southern Europe

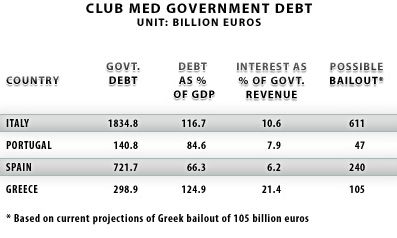

known as “Club Med.” The next in line after Portugal is Spain, a country with

unemployment in excess of 20 percent and considerable private sector

indebtedness, after which is Italy, which has the highest ratio of debt to

gross national product (GDP) in Europe after Greece.

However, the risk of

contagion is not necessarily just about macroeconomic fundamentals any longer.

The rest of the Club Med countries are not at same level of crisis as Greece.

For instance, while Italy comes close in the ratio of government debt to GDP,

it has much more comfortable debt interest payments in terms of government

revenue. The interest-to-revenue ratio is a key indicator of a government’s

ability to get through the crisis, and it is one Greece is outright failing on.

Athens currently spends 1 out of every 5 euros of revenue on servicing its

debts, and as Athens’ financing costs and stock of debt are both increasing,

while its economy continues to contract, it is highly likely that the

proportion of revenue Athens spends on debt service payments will only

increase.

Nonetheless, many

investors currently are betting Greece is not going to get out of the crisis

and, in due time, neither will Portugal. This assessment is based largely on

the holdups in financial aid from the eurozone and International Monetary Fund

(IMF). While Europe has negotiated the conditional bailout package

intermittently since February, and ostensibly agreed to the terms in March, the

delays continue. Greece has yet to receive any eurozone or IMF funds.

This means that at

this point, perhaps only a “shock and awe” bailout plan will be sufficient to

reassure the markets that the eurozone stands behind Greece and will not allow

it to fail. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is now considering between

100 billion euros ($131 billion) and 120 billion euros for a three-year package

and that it is negotiating an increased figure of 25 billion euros (up from 15

billion euros) for this year alone. This means the eurozone contribution would

be somewhere in the range of 80 billion euros, and eurozone leaders are in fact

considering taking such action.

This gradual increase

in bailout size reminds of the debates during the Russian financial crisis in

1997-1998. In mid-June 1998, the numbers were in the $5 billion to $10 billion

range and increased to $20 billion a month later. The package the IMF

ultimately agreed on was $22.6 billion, but the crisis deepened shortly

thereafter, as the numbers debated by IMF officials and various commentators

went up to $35 billion, then $75 billion and then in excess of $100 billion.

Ultimately, Russia defaulted on its debt in the following months, when only

$5.5 billion had been dispersed by the IMF.

The alternative to

the above scenario is the U.S. bailout of its financial sector following the

subprime lending crisis that kicked off in late 2007. Once the intense

political debate concluded, the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) package

was larger than anticipated, totaling some $700 billion. It was just the first

of a number of bailout packages. In total, the United States supported the

economy with spending, loans and guarantees amounting to about $13 trillion, although

only about $4 trillion has been actually called on.

These are the kind of

shock-and-awe numbers Europe may be looking at as well. If we take the figure

of 105 billion euros as the most likely Greek bailout (roughly a third of its

outstanding debt) and assume proportional assistance to the other Club Med

states, the total eurozone bailout for Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy would

be in the realm of 1 trillion euro, double the initial size of TARP. And just

like the United States, the eurozone may be faced with a succession of other

bailouts down the line.

However, the question

is whether there is enough political will (not to mention actual cash or

credit) to carry out such a large bailout, especially considering that Germany

has struggled with the idea of just a 30 billion euro commitment from the

eurozone, of which Berlin would contribute 8.4 billion. An increase to 80

billion, using the same ratio and assuming that Club Med would be unable to pay

its share, would mean Berlin would have to pay approximately around 35 billion

euros. That would greatly increase resistance in Germany, which essentially is

faced with a decision of whether it wants to pay for its leadership of the

eurozone, and could stall the process even further.

Some Other Obstacles

Greece itself. Greece

has a very generous social welfare system, far more generous than Germany’s, so

it will resist any more budget cuts. In many ways, this is an extension of the

attitude that got Athens into trouble in the first place.

Germany. Fresh from

making years of budget cuts itself, Berlin does not want to pay for Greece to

live the good life. It will push for more austerity like the IMF, for deep

EU/German control over the Greek finance ministry, or both.

Legal complications.

This is all technically unconstitutional and some of this might require

parliamentary approval. Should a single contributing state for whatever reason

not belly up to the bar, the whole thing could unravel. (Why should Vienna pay

if Madrid refuses to?) The ad hoc nature of this also presents problems: States

will be asked to pay into the Greek kitty in proportion to their economic size

based on their ongoing contributions to the EU budget. That will not sit well

with states in recession and those that are normally net providers of EU funds

but get relatively little back.

The German finance

ministry has already laid out a six-step process for approving a bailout.

First, Greece must officially ask, which it has. Second, the Europeans must

examine if Greece really needs the help. Third, Greece must submit a

restructuring plan to bring their budget back into balance. Fourth, the

potential funders must approve this plan. Fifth, everything must be submitted

to the European Council and the European Central Bank for approval. And sixth,

this finalized proposal must then be approved by the German parliament. Put

simply, all the sound and fury surrounding the Greek economy to this point has

been the preamble. Only now are the Europeans – led by the Germans – getting

down to brass tacks.

For updates

click homepage here