In

my previous link I expressed suspicion that the

rebels harbor a non-Libyan hard core of professional soldiers. Yesterday then

British newspapers came out with the fact that “for

several weeks” British special forces have been on the ground aiding

rebels, and played a key role in coordinating the march on Tripoli.

Today

various Middle East Newspapers furthermore report that when Aug. 20, Lt. Gen.

Charles Bouchard, NATO's Canadian commander in Libya, gave the signal for the

advance on Tripoli, Special Operations units had been standing by in

safe-houses around the city; weapons, ammunition, food and water had been

cached at dozens of points close to the action, at the international airport at

Ben Ghashir 34 kilometers south of the city center and around Tripoli port.

As

a result rebels in Tripoli were able to successfully seize Gadhafi’s Bab

al-Aziziya compound Aug. 23. Yet Gadhafi, his family and what is left of his

inner circle remain at large. There have been constant rumors about the

locations of all of these individuals, ranging from parts of Tripoli, to Sirte,

Sabha, Algeria and the southern desert.

Gadhafi

has made three statements broadcast on radio stations loyal to him since the

rebel entry into Tripoli. Rebels searching the Bab al-Aziziya compound Aug. 25

discovered an intricate system of tunnels and bunkers believed to lead to

various exit points outside the compound’s walls; unconfirmed reports allege

that the system contains at least one tunnel that extends more than 30

kilometers (about 18 miles) beyond the compound’s walls. Reports that some

rebel fighters encountered small arms fire within the tunnels indicates Gadhafi

loyalists have been using them to escape the compound.

Reuters

reported that Gaddafi might try to sell part of Libya's gold reserves to

pay for his protection and sow chaos among tribes

in the north African country.

Hence

not until Gadhafi is in custody or dead will the Libyan war be over.

It

is expected that the rebel Transitional National Council will soon move from

Benghazi to Tripoli. Even when the odds on the flare-up of civil and tribal

warfare at the moment there still is only a 50/50 chance of the TNC being able to make good on

its pledges to establish stable governing institutions and call Libya's first

ever general election in eight months time.

With

help of NATO the new regime will start out with an army and police force at its

disposal and most likely establish its seat in Gadhafi 's old stronghold, the

Bab al-Aziziya compound, which will assume the character of the US-Iraqi-

controlled Green Zone of Baghdad.

To

safeguard this area of some six square kilometers in the heart of Tripoli, NATO

will need at least one armored division along with aerial surveillance units,

special operations forces trained in urban combat, engineering forces and

intelligence units – including field intelligence and electronic surveillance.

Given

the rebels now, not only, receive help from British special forces, it is to be

expected that they will conquer Tripoli within a week. And if the deposed ruler

is caught within a few days, which the British and French think is possible,

his support system may founder with him. But not if the hunt drags out for

long. Because if so, that would mean he has the administrative machinery for

continuing to rule parts of Libya in the south and west. The forces stationed

outside Tripoli during the city's fall remain in control of the region around

his tribal hometown of Sirte east of Tripoli and the Fezzan area in southwest

Libya, where most of the Libyan oilfields are located. And Gadhafi will

meanwhile rally the tribal chiefs, first to secure their own territory and

second to put up recruits to fight under his flag.

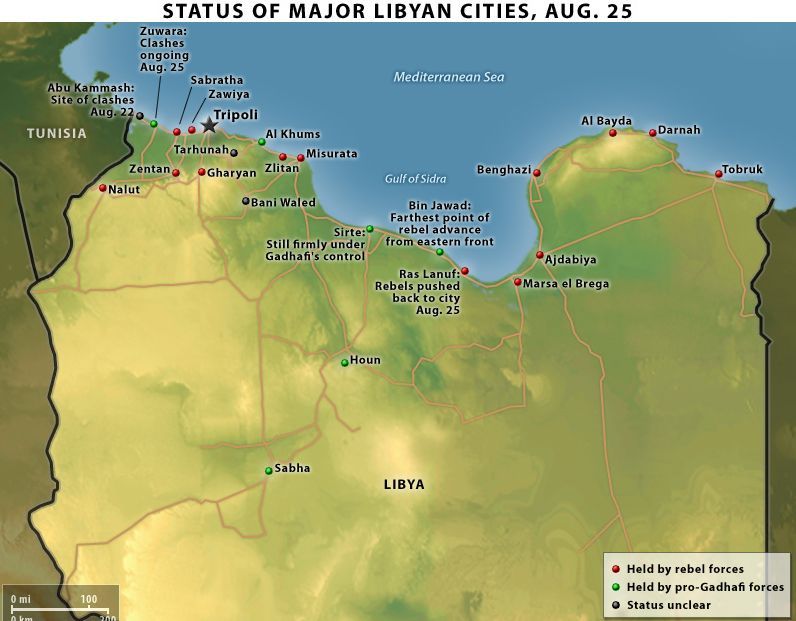

Outside

the capital there are ongoing clashes near the Ras Ajdir checkpoint at the

Tunisian border on the western Libyan coast, including the Aug. 25 death of a

Tunisian fisherman by a stray bullet fired during a minor naval skirmish

between pro-Gadhafi forces and rebel fighters, have led the Tunisian government

to close the border there. The major town in this region is Zuwarah, the site

of an army base the rebels reportedly took Aug. 24. Pro-Gadhafi forces are

still fighting throughout the area after being cut off from the capital by the

rebel seizure of Zawiya on Aug. 18.

The

only area where Gadhafi’s forces have actually gained territory since the

rebels entered Tripoli on Aug. 21 is on the far eastern front. After retreating

to the town of Bin Jawad earlier in the week, pro-Gadhafi forces regained

ground Aug. 25 when they pushed rebel fighters back to the port town of Ras

Lanuf. This back-and-forth on the eastern front happened often in the early

days of the Libyan war, but the inability of rebel forces in the east to make

significant progress despite their recent momentum of rebel forces elsewhere

has left Gadhafi’s home region of Sirte untouched by anything other than

reportedly sporadic NATO bombing. The rebel fighters on this front have

publicly expressed surprise that Gadhafi’s forces did not fold after the public

entrance of rebel fighters into Tripoli and have also begun to express concerns

about supply lines necessary to make an effective push on Sirte. Rebel fighters

that have extended their front southeastward from Misurata also have not been

able to reach the outskirts of Sirte.

Forces

loyal to Gadhafi continue to control the central desert town of Sabha, which

has a population of more than 200,000, rivaling Zawiya in size. Like Sirte,

Gadhafi also has ties to Sabha, having attended secondary school there, and the

Libyan army maintains a base in the city. Though reports began to trickle out

Aug. 25 that rebel fighters had seized a main street in Sabha, this is

unlikely, as it is located extremely far from any of the other rebel positions

in northern Libya.

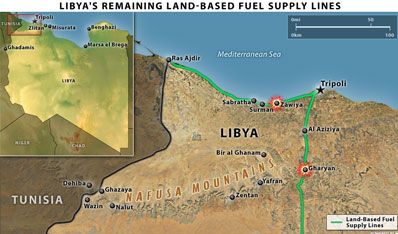

However

rebels are rumored to now travel towards the Ras Ajdir border crossing between

Libya and Tunisia, and if the rebel's would win there, it should help open

supply routes, to bring in much needed aid to the capital of Tripoli.

What

next with Libya?

With

the end of the Gadhafi regime seemingly in sight, we need to look at the

reality of what next with Libya. As Libya enters this critical juncture and the

National Transitional Council (NTC) transitions from breaking things to

building things and running a country, there will be important fault lines to

watch in order to envision what Libya will become.

In

fact it has proven to be rather difficult to build a stable government from the

remnants of a long-established dictatorial regime. History is replete with

examples of coalition fronts that united to overthrow an oppressive regime but

then splintered and fell into internal fighting once the regime they fought

against was toppled. In some cases, the power struggle resulted in a civil war

more brutal than the one that brought down the regime. In other cases, this

factional strife resulted in anarchy that lasted for years as the iron fist

that kept ethnic and sectarian tensions in check was suddenly removed, allowing

those issues to re-emerge.

One

of the biggest problems that will confront the Libyan rebels as they make the

transition from rebels to rulers are the country’s historic

ethnic, tribal and regional splits. While the Libyan people are

almost entirely Muslim and predominantly Arab, there are several divisions

among them. These include ethnic differences in the form of Berbers in the

Nafusa Mountains, Tuaregs in the southwestern desert region of Fezzan and Toubou

in the Cyrenaican portion of the Sahara Desert. Among the Arabs who form the

bulk of the Libyan population, there are also hundreds of different tribes and

multiple dialects of spoken Arabic.

Perhaps

most prominent of these fault lines is the one that exists between the ancient

regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. The Cyrenaica region has a long and rich

history, dating back to the 7th century B.C. The region has seen many rulers,

including Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Ottomans, Italians and the British. Cyrenaica

has long been at odds with the rival province of Tripolitania, which was

founded by the Phoenicians but later conquered by Greeks from Cyrenaica. This

duality was highlighted by the fact that from the time of Libya’s independence

through the reign of King Idris I (1951-1969), Libya effectively had two

capitals. While Tripoli was the official capital in the west, Benghazi, King

Idris’ power base, was the de facto capital in the east. It was only after the

1969 military coup that brought Col. Moammar Gadhafi to power that Tripoli was

firmly established as the seat of power over all of Libya. Interestingly, the

fighting on the eastern front in the Libyan civil war had been stalled for

several months in the approximate area of the divide between Cyrenaica and

Tripolitania.

While

the NTC is an umbrella group comprising most of the groups that oppose Gadhafi,

the bulk of the NTC leadership hails from Cyrenaica. In its present state, the

NTC faces a difficult task in balancing all the demands and interests of the

various factions that have combined their efforts to oust the Gadhafi regime.

But many past revolutions have reached a precarious situation once the main

unifying goal has been achieved: With the regime overthrown, the various

factions involved in the revolution begin to pursue their own interests and

objectives, which often run contrary to those of other factions.

In

most of these past cases, including Afghanistan, Somalia and Nicaragua, the

internal fault lines were seized upon by outside powers, which then attempted

to manipulate one of the factions in order to gain influence in the country. In

Afghanistan, for example, warlords backed by Pakistan, Iran, Russia and India

were all vying for control of the country. In Somalia, the Ethiopians,

Eritreans and Kenyans have been heavily involved, and in Nicaragua, contra

groups backed by the United States opposed the Cuban- and Soviet-backed

Sandinistas.

Outside

influence exploiting regional and tribal fault lines is also a potential danger

in Libya. Egypt is a relatively powerful neighbor that has long tried to meddle

in Libya and has long coveted its energy wealth. While Egypt is currently

focused on its own internal issues as well as the Israel/Palestinian issue, its

attention could very well return to Libya in the future. Italy, the United

Kingdom and France also have a history of involvement in Libya. Its provinces

were Italian colonies from 1911 until they were conquered by allied troops in

the North African campaign in 1943. The British then controlled Tripolitania

and Cyrenaica and the French controlled Fezzan province until Libyan

independence in 1951. It is no accident that France and the United Kingdom led

the calls for NATO intervention in Libya following the February uprising, and

the Italians became very involved once they jumped on the bandwagon. It is

believed that oil companies from these countries as well as the United States

and Canada will be in a prime position to continue to work Libya’s oil fields.

Qatar, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates also played important roles in

supporting the rebels, and it is believed they will continue to have influence

with the rebel leadership.

Following

the discovery of oil in Libya in 1959, British, American and Italian oil

companies were very involved in developing the Libyan oil industry. In response

to this involvement, anti-Western sentiment emerged as a significant part of

Gadhafi’s Nasserite ideology and rhetoric, and there has been near-constant

friction between Gadhafi and the West. Due to this friction, Gadhafi has long

enjoyed a close relationship with the Soviet Union and later Russia, which has

supplied him with the bulk of his weaponry. It is believed that Russia, which

seemed to place its bet on Gadhafi’s survival and has not recognized the NTC,

will be among the big losers of influence in Libya once the rebels assume

power. However, it must be remembered that the Russians are quite adept at

human intelligence and they maintain varying degrees of contact with some of

the former Gadhafi officials who have defected to the rebel side. Hence, the

Russians cannot be completely dismissed.

China

also has long been interested in the resources of Africa and North Africa, and

Gadhafi has resisted what he considers Chinese economic imperialism in the

region. That said, China has a lot of cash to throw around, and while it has no

substantial stake in Libya’s oil fields, it reportedly has invested some $20

billion in Libya’s energy sector, and large Chinese engineering firms have been

involved in construction and oil infrastructure projects in the country. China

remains heavily dependent on foreign oil, most of which comes from the Middle

East, so it has an interest in seeing the political stability in Libya that

will allow the oil to flow. Chinese cash could also look very appealing to a

rebel government seeking to rebuild — especially during a period of economic

austerity in Europe and the United States, and the Chinese have already made

inroads with the NTC by providing monetary aid to Benghazi.

The

outside actors seeking to take advantage of Libya’s fault lines do not

necessarily need to be nation-states. It is clear that jihadist groups such as

the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb see the

tumult in Libya as a huge opportunity. The iron fist that crushed Libyan

jihadists for so long has been destroyed and the government that replaces the

Gadhafi regime is likely to be weaker and less capable of stamping down the

flames of jihadist ideology. There are some who have posited that the Arab

Spring has destroyed the ideology of jihadism, but that is far from the case.

Even had the Arab Spring ushered in substantial change in the Arab World — and

we believe it has resulted in far less change than many have ascribed to it— it

is difficult to destroy an ideology overnight. Jihadism will continue to affect

the world for years to come, even if it does begin to decline in popularity.

Also, it is important to remember that the Arab Spring movement may limit the

spread of jihadist ideology in situations where people believe they have more

freedom and economic opportunity after the Arab Spring uprisings. But in places

where people perceive their conditions have worsened, or where the Arab Spring

brought little or no change to their conditions, their disillusionment could

create a ripe recruitment opportunity for jihadists.

The

jihadist ideology has indeed fallen on hard times in recent years, but there

remain many hardcore, committed jihadists who will not easily abandon their

beliefs. And it is interesting to note that a surprisingly large number of

Libyans have long been in senior al Qaeda positions, and in places like Iraq,

Libyans provided a disproportionate number of foreign fighters to jihadist

groups.

It

is unlikely that such individuals will abandon their beliefs, and these beliefs

dictate that they will become disenchanted with the NTC leadership if it opts

for anything short of a government based on a strict interpretation of Shariah.

This jihadist element of the rebel coalition appears to have reared its head

recently with the assassination of former NTC military head Abdel Fattah Younis

in late July (though we have yet to see solid, confirmed reporting of the

circumstances surrounding his death).

Between

the seizure of former Gadhafi arms depots and the arms provided to the rebels

by outside powers, as pointed out above, Libya is awash with weapons. If the

NTC fractures like past rebel coalitions, it could set the stage for a long and

bloody civil war — and provide an excellent opportunity to jihadist elements.

At present, however, it is too soon to forecast exactly what will happen once

the rebels assume power. The key thing to watch for now is pressure along the

fault lines where Libya’s future will likely be decided.

![]()