By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Why hunter-gatherer societies were

more complex than we previously imagined, and civilization did not start the

places like Greece

As we have

seen earlier, despite the fantasies of earlier writers about Archeology in

Mesopotamia, it is notoriously hard to find palaces in the usual sense of the

word. In the Late Uruk period,

"palace" is termed because it is large and has a different plan than

temples. In the Early Dynastic, the "palaces" were designated because

their shapes were not temple-like. In the Third Dynasty of Ur, there were

temples and ziggurats at the end of the third millennium BC, and we have a list

of kings, but where is the palace?

There was a Ciutadella for

public ceremonies, but there are only arguments about the existence of a royal

residence. In Mesopotamia, temples are built and re-built on sacred land. On

the other hand, palaces are personal residences and administrative seats of

rulers who build them in places distant from the palaces of former kings or

historical venues of state ceremonies. Indus Valley city-states look different

from Mesopotamian city-states. They were ruled differently and seemed to have

different rules about how power was exhibited. Their development and collapse

were also different from what they were in Mesopotamia.

No state evolved without the potential

to produce large and regular surpluses that could be stored for years. Base

camps of hunter-gatherers were transformed into relatively long-lasting

villages that subsisted on the emerging plenty and eventually on domesticated

plants and animals. Village agriculture narrowed the choices of resources and

led to population growth. Given the specific biological changes in humans that

prevailed towards the end of the Pleistocene, there was a gradual development,

both in the term's demographic and social sense, that was irreversible. The

growth processes were not characterized by stable systems whose limitations had

to be overcome but by the constant change in unstable post-Pleistocene

societies.

We have elaborated this growth model by

noting that the earliest villages in Mesopotamia persisted as modest

villages for thousands of years, while social roles and identities changed

significantly. From the environment of village life, the circulation of goods

and marital partners led to institutionalized interconnections among unrelated

people and the formation of interaction spheres. Codes of communication and

symbols of shared beliefs allowed and expressed new aspects of cultural

identity among villagers. Specific individuals, nascent elites, began to access

the technology of symbol manufacture and the means of communication and

communication venues such as feasts and ceremonies. Control over these symbols

and esoteric knowledge became a domain of power in these early villages.

The earliest states appeared in the Old

and New World approximately four to five thousand years after the first settled

villages that depended on agriculture. Agricultural villages were the necessary

but not sufficient conditions for the evolution of the earliest states. Towards

the end of the Pleistocene period, which was very cold and dry, Upper

Paleolithic hunters and gatherers had invented new technologies that allowed

them to expand their subsistence strategies and establish campsites. In the

cycles of amelioration of the harsh climatic conditions at the beginning of the

Holocene in Mesopotamia, following 10,000 BC,' natural resources for people

flourished, and bands of people, probably extended families, founded

longer-lasting settlements. These settlements subsisted on the extensive stands

of grasses and other local resources.

Some of these earliest village sites in

the 9000's and 8000's BC, like Abu Hureyra 1

(the early occupation) in Syria and Hallan Çemi in

Anatolia, were pre-agricultural villages, were by no means small (Abu Hureyra was about ten hectares in size).

At Hallan Çemi, considerable feasting

and ceremony occurred - celebrations of residence, as it were. Nemrik, Qermez Dere (both

in northern Iraq), and Abu Hureyrâ and Mureybit (both in Syria), in the later 8000's and

7000s, were villages in which plants and animals were domesticated after the

sites were founded. Domestication occurred not to relieve hunger but as a

process whereby humans increasingly selected, as part of collection,

processing, and reseeding activities, certain genetically recessive traits in

the grasses, such as hardiness of plant stems and seeds, at the expense of

dominant features that allowed stands of grains to reproduce effectively

without human intervention. The seeds from recessive phenotype plants were

quickly collected, then; stored and subsequently planted; fields had to be

weeded to keep out the dominant forms. People also selected smaller and gentler

animals, had more wool, or possessed other traits that made them useful to

sedentary people, who protected them from wild competitors. Some early villages

were impressive features in the landscape. At the site of Göbekli Tepe, megaliths and pillars were erected, some

weighing about 50 tons, indicating the labor of many people, more than could

have existed in any village. Furthermore, there seem to be no domestic quarters

at Göbekli Tepe, and the entire site

"served a mainly ritual function" for those in this region,

settled people, and mobile ones alike.

Thus, it appears that in the 7000's and

early 6000's people founded villages in new niches, both in the natural habitat

zone of wild plants and animals and increasingly to the south along the

Mesopotamian plain and away from the region that was the scene of the first

villages.

In fact, Göbekli Tepe

is not the only such place. During the 1970s, the Taljanky(1)

and Nebelivka, or Nebelovka,

located in Ukraine, are the site of an ancient mega-settlement dating to 4000

BC belonging to the Cucuteni-Trypillian

culture(Romanian: Cultura Cucuteni and Ukrainian: Трипільська культура), also known

as the Tripolye culture (Russian: Трипольская

культура), is a Neolithic–Eneolithic archaeological

culture (c. 5500 to 2750 BCE) of Eastern Europe.

It extended from the Carpathian Mountains to the

Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering

substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania.

A millennium and a half after Göbekli Tepe, once called Asia Minor now Anatolia, about

8,000 people settled in Catalhöyiik. No longer

living as hunter-gatherers, as did the people surrounding Göbekli

Tepe, the Catalhöyiik people grew wheat, barley,

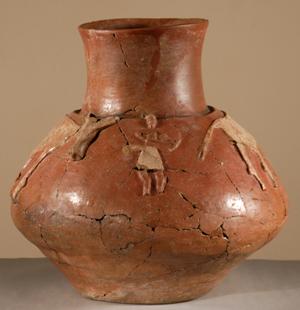

lentils, and peas, and they herded sheep and goats. A group of larger figures,

made of clay, were found in a single building and dated to around 7,500 years

ago. A fat woman seated in a chair; between her feet protrudes a small human

head, presumably a child to whom she has just given birth; the arms of the

chair are formed by two large standing cats, whose tails curve up over her

shoulders; her hands rest on their heads. It should be empesised

however that both sexes are shown in the of Catalhöyiiki

including sites like Nevalli Cöri

in the same region. Anthropologists believe that the female figures

are meant to be deities in a way that the male figures are not. But

wathever the final evidence will proof the following

item dating from six thousand years BC, is from long before Laws of Solon (d.

558 BCE):

For updates

click homepage here