Recent travelers to

the Caspian Sea nations of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Georgia and Turkmenistan

report burning interest in the spiraling tussle between Russia and Iran over

control of the Caspian, the largest inland sea in the world and repository of

some of its richest natural resources – even to the exclusion of the nuclear

aspirations of their southern neighbor and Caspian partner, Iran.

In Tiblisi, Baku, Ashgabat and Astana, high officials,

political military, intelligence and financial, told our sources that this

started when Russian-Iranian relations went downhill at President Vladimir

Putin’s visit Tehran on Oct. 16. A senior official in Baku said Putin and his

Iranian hosts fell out less over Tehran’s disputed nuclear activities and much

more over “Iran’s frustration at Moscow’s success in seizing control of 90

percent of the Caspian region’s oil and gas exports.”

The official said:

“You will find Russia’s heavy hand on every source of revenue from oil and gas

and on every tap controlling pipeline transport of oil and gas to Europe and

China. Moscow’s expanding influence in Caspian republics has reached the point of

jeopardizing Iran’s national interests.”

At the Caspian Summit

in Tehran last month, Putin outmaneuvered the Iranian president by thwarting

every attempt to carry a resolution regulating common exploration of the

resources buried in the Caspian seabed. In the absence of this accord, the

Caspian coastal nations are prevented from reaching the resources under their

sections of the sea. In consequence, energy prices continue to rocket on the

world market.

As seen by local

sources in Caspian capitals, Moscow’s takeover was finally in the bag when the

post-Soviet ruler of Turkmenistan, the eccentric Saparmurat Niyazov, died

suddenly in Dec. 2006. This five million-strong Muslim nation sits on the

world’s fourth or fifth largest reserves of natural gas, ranging from 2 to 20

trillion cubic meters. Most of it is situated under the vast Kara-Kum (Black

Sands) desert. Current production is roughly 70 billion cubic meters annually.

This should be tripled by 2030.

Claims are,

that elements close to Russian intelligence assassinated Niyazov, when he

was on the point of breaking free of Russia’s grip and turning to the West. He

wanted to import foreign experts to carry out offshore exploration in the

Caspian Sea. One source in Ashghabat explained that

the dead Turkmen ruler had grasped a fact only now dawning on Tehran that, in

pulling the strings of his government’s energy and exporting policy, Moscow was

solely motivated by its own regional and global interests.

It is a fact, that

Moscow pays us $100 for a cubic meter of gas and flogs it to the Europeans for

$280-300. “When the Russians discovered Niyazov secretly casting about for

Western patrons, they cooked his goose,” one official said. It was therefore

with astonishment that knowledgeable officials in the region learned that

Niyazov’s successor, President Kurbanguly

Berdymukhamedov (the Kremlin’s man), who took office in February, was being

greeted in the West as more accessible and outwardly-oriented than his

predecessor.

A Turkmen energy

delegation was received in Washington and Houston. In mid-November, US

secretary of energy Samuel Bodman and his European counterpart visited Ashgabat

with a flock of energy executives.Interest in

exploration deals with Turkmenistan, which was closed for years to Western

firms, comes from Chevron, Conoco Phillips and Exxon Mobil, as well as European

firms, some of whom are already heavily invested in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

Today, the extensive

network controlled by Russia virtually monopolizes the region’s gas exports.

Most analysts agree that the geopolitical struggle over energy resources in

this coveted region is acute. In terms of geographic proximity, Russia has the

upper hand over the Americans – especially since Washington decided to give ground to Moscow in its back yard under the influence of the new thaw

between President George W. Bush and Putin. Bush seeks new Pact with Putin for

Crackdown on Iran).

Full development of

the Caspian gas fields following major discoveries is estimated in terms of

decades. But even before a major network is developed, the pipeline battle has

already begun. One of the few places in the Caspian region where Moscow has given

ground to US interests is Azerbaijan. There, the Kremlin acknowledges the

prevalence of US influence and the strong ties President Ilham Aliyev has

forged with Washington.

Even so, high-placed

quarters in Baku warn that this may be no more than a tactical retreat and the

Russians may suddenly leap into the fray. They are therefore keeping a watchful

eye on how events develop around the new gas pipeline linking the gas networks

of Turkey and Greece, which was inaugurated at Ipsala,

Turkey on Nov. 17. Present at the ceremony were Aliyev, the prime ministers of

Turkey and Greece, Tayyep Recep Erdogan and Costas

Karamanlis, Georgia’s energy minister Nika Gilauri

and the US secretary of energy Samuel Bodman.

This pipeline makes

it possible to export Azerbaijani gas from the Caspian Sea’s Shahdeniz deposit to Greece, a European Union member. Its

extension in 2010 will bring natural gas from Azerbaijan up to Greece and on to

Italy. This project is vital because it brings gas to Europe by an alternative

to the Russian route. Azeri officials are wondering if they will get away with

this breach of the Russian monopoly over the export of Caspian gas.

For the moment,

Moscow has let it happen, conscious that it can shut the pipeline down at will

by activating Georgian opposition elements whose leader, the Georgian tycoon

Badri Patarkatsishvili, is in the Kremlin’s pocket.

All the pipelines

bypassing the Russian network from the Caspian to Europe must transit Georgia.

Moscow is keeping the pro-Western government of Mikheil Saakashvili on the boil

and therefore a potentially weak link in the alternative energy chain feeding

Europe. Patarkatsishvili can be ordered to stage anti-government riots in Tiblisi and the Georgian section of the pipeline may be

mysteriously sabotaged. European energy consumers would then have to resort to

Moscow pipelines for their energy.

A foretaste of the

Kremlin’s power to destabilize the Tbilisi government was provided when

Saakashvili was forced to call snap elections following a brief state of

emergency declared to subdue unrest in the capital fomented by the pro-Moscow

opposition. The emergency was lifted on Nov. 16, marking the most serious

political crisis the former Soviet republic has faced since its bloodless

revolution four years ago. Saakashvili accused Moscow’s intelligence services

of stirring the unrest.

At the same time, the

Kremlin may have decided, for the time being, to keep its hands off the

Azerbaijan pipeline to Europe in order to foster the new understanding

unfolding between Putin and George W, Bush (mentioned by us on Nov.7 further

down this website).

Bush for his part is

backing away from vying with Moscow over military and economic footholds in the

Caucasian, Caspian and Central Asian regions.

The Kremlin is also

facing a challenge on another front, Moscow sources report that Tehran, which

accuses Moscow of seizing control over 90 percent of the Caspian region’s oil

and gas exports and robbing Iran of its share, is getting its own back. The Iranians

have embarked on a project which too aims at breaking the Russian grip on

energy exports to Europe, while also gaining a lever of their own on the

continent.

They have therefore

propositioned the European Union with an offer of large quantities of natural

gas to be carried through the projected Nabucco pipeline, which is planned to

run from Azerbaijan to Austria via Turkey. Construction by an Austrian-led consortium

will start next year and be completed by 2011, with an investment of some five

million euros.

Moscow is furious

over the Iranian initiative. Because its implementation would reduce Europe’s

dependence on Russia for its natural gas needs. Germany, in particular, relies

on Russia for a third of its gas requirements and consumption will increase. Russia’s

European clients have felt deeply insecure since Moscow cut off energy supplies

to Ukraine and Belarus, and have been casting about for alternative energy

sources and supply routes.

Of course power

struggles are common in the world of politics so also between the right and

left hand of Russian President Vladimir Putin: Igor Sechin and Vladislav

Surkov. The two men have been Putin's confidants and enforcers for years. With

Putin, they form the core of true power in Moscow.

For most of the past

five years they have also, been circling each other via their power bases-

state oil firm Rosneft for Sechin, state natural gas firm Gazprom for Surkov-

and attempting to strengthen their respective firms, whether at each other's

expense or not. Yukos has been the largest casualty of this battle.

Rosneft's rivalry

with Gazprom has landed the company in a dangerous financial situation. The

company has about $9 billion of debt, nearly all of which is due within the

next few months. Rosneft accumulated the debt during the battle to steal away

pieces of Yukos before Gazprom bought them, and is now in financial trouble.

Government taxes on oil extraction are designed to shuffle the windfall from

high prices to the government, so even seeing oil prices north of $90 is not

granting Rosneft appreciable financial help. The pressure is so heavy that

Rosneft is now considering selling most of the former Yukos assets, but the

only firms with the financial wherewithal to bid for them are either

Gazprom-friendly, or Gazprom itself.

Instead, Sechin wants

to tap into Russia's $158 billion oil stabilization fund, the pool into which

Russia's excess oil revenues are held for a rainy day, to take care of the

debt. To Sechin this makes perfect sense: Rosneft is a state-owned company, and

the stabilization fund exists because of surplus oil revenues.

But Deputy Prime

Minister and Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, who oversees the fund, does not

agree with Sechin's logic. Kudrin is a technocrat that Putin trusts to balance

the books. Though he is personally closer to those within the Gazprom clan, he

has not allowed this to sway him on important financial decisions. He truly is

a dispassionate accountant who believes in strict controls on government

spending. That dispassion is directly responsible for the solid financial

recovery of the Russian government after the bankruptcy of the 1990s.

Now Sechin is

striking out at Kudrin by picking off his closest advisers. In an obvious move

against Kudrin, Sechin had Vice Minister of Finance Sergei Storchak

and his two associates arrested Oct. 16 on charges of trying to divert $43.4

million dollars from public funds.

Looking at these

developments from another angle, the Moscow-Tehran energy duel can be seen

running parallel to the ascending Washington-Tehran showdown over Iran’s banned

nuclear activities. Given their common adversary, Washington and Moscow have

good reason to cooperate on major global issues, provided that the Bush

administration respects Russia’s interests in its immediate neighborhood.

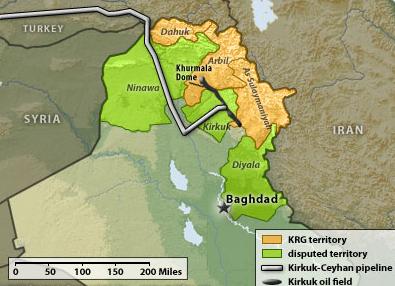

To complicate the

issue the central Asian Ceyhan pipeline most recently also carries prized

Kirkuk oil, which is estimated to hold more than 15 billion of Iraq's 115

billion barrels of proven oil reserves. Currently, the Kirkuk region lies

outside of the KRG's established boundaries, but a constitutionally mandated

referendum is supposed to take place by year's end to decide whether Kirkuk,

along with the Diyala and Ninawa provinces, will become part of the Kurdistan

region. Though the referendum deadline will be missed, Kirkuk will become the

battleground for the Kurds and their surrounding adversaries.

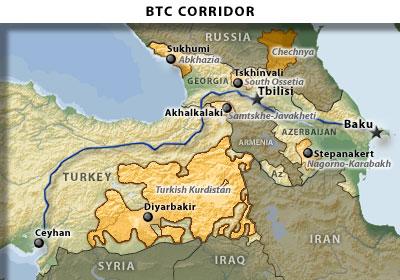

As is known, Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili and Azerbaijani President

Ilham Aliyev opened a new oil terminal Nov. 21 in Georgia's Black Sea port of Kulevi. This Kulevi oil terminal

a few days ago started to supply the West with crude oil and refined

products from Azerbaijan, which has received increasing attention as Europe

looks to decrease its energy dependence on politically hot countries such as

Russia, and as Azerbaijan seeks export options outside its typical use of

Russian energy infrastructure. Azerbaijan and Europe have built this

energy relationship, with the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline.

Energy wealth has doubled

Azerbaijan's gross domestic product, but the sudden wealth is very worrying to

certain of Azerbaijan's neighbors because the majority of the money is going

toward defense. Azerbaijan's defense budget has jumped from just a few hundred

million a year to a billion this past year. The country is arming itself, and

neighboring Armenia is closely watching. The two countries have been deadlocked

over the Azerbaijani secessionist region of Nagorno-Karabakh -- a conflict that

has flared into a war in the past. Azerbaijan's armament now has many wondering

if Baku is planning another conflict against a neighbor that has been cut out

of the region's recent energy wealth.

What is intriguing

about the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline, showing indeed what we mean

with future Central Asian conflicts, is that it carries oil interests that

reaches all the way into Iraq. And from that end at least, some kind of battle

might soon be under way; because Iraq's Shiite-dominated Oil Ministry is now

accusing the KRG of blocking central government work on the Kirkuk oil field

over the past three months. Though there are conflicting reports between the

ministry and the government official in charge of the project, the ministry

claims that the KRG sent Peshmerga armed forces to prevent the State Company

for Oil Projects (an extension of the ministry) from upgrading the Khurmala Dome of the Kirkuk field.

The Kirkuk field

encompasses three domes, Khurmala, Baba and Avana,

with the Khurmala Dome at the northern tip. The

entire field produces between a quarter-million and a half-million barrels per

day (bpd), with the Khurmala project expected to add

another 100,000 bpd. The two main domes, Baba and Avana, are in Kirkuk,

territory that is currently under dispute. However, the Khurmala

Dome falls in Arbil, which is technically within the KRG's borders. As a

result, the central government has agreed to let the KRG take part in operating

the Khurmala Dome portion of the field, though that

agreement rests on a shaky foundation.The KRG thus is

taking a calculated risk by pushing for more control over the Kirkuk oil field.

And while the Kurds can make money selling oil domestically, the big

bucks lie in bringing northern Iraq's oil field up to production levels that

can service the foreign market.

For updates

click homepage here