Other subjects I have covered in the recent past are that of Europe, Russia, South Asia, the USA, the South China Sea debacle, and most recently also Brexit in a world that is going

through changes.

Europe

Judging by the behavior of British Prime Minister Theresa May’s

diplomats, one might believe that Brexit is the only real uncertainty nowadays.

Indeed, they seem convinced that their only imperative – beyond protecting the

unity of the Conservative Party, of course – is to

secure as many benefits for the UK as possible.

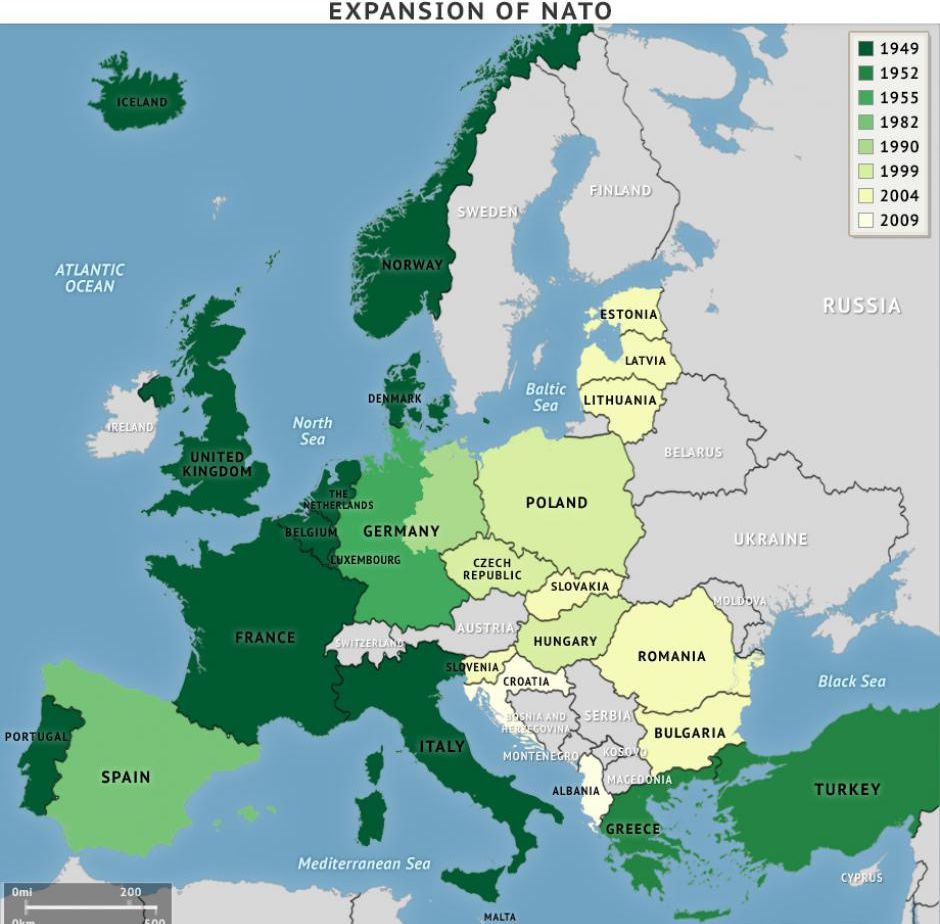

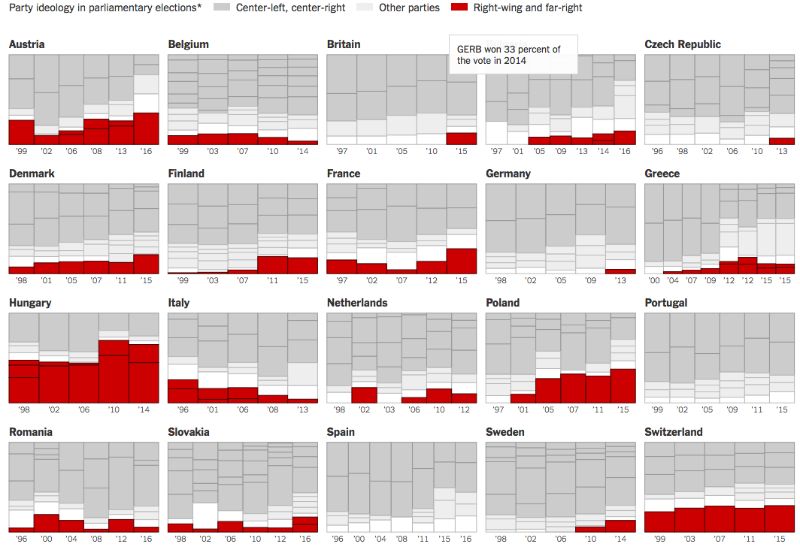

This while the upsurge of populism in Europe has provided

Russia with an ample supply of sympathetic political parties across Europe.

These parties – mostly from the far right but also from the far left – are

pursuing policies and taking positions that advance Russia’s agenda in Europe.

Of course for Europe, the political and economic risk is nothing new.

For years, nationalism, populism, conflicting strategic interests, low economic

growth and high unemployment have driven EU members apart.

This while NATO's indecision benefits its opponents and proves that if

the alliance is to endure, it must identify a clear enemy, or move beyond the

need for one.

Security and immigration will feature prominently in the German

electoral campaign. The right-wing opposition and even some members of Chancellor

Angela Merkel's coalition will push for tougher immigration legislation and for

granting more resources to security forces. The general election will show that

German voters are willing to support smaller parties on the left and the right.

This will probably lead to a more divided parliament and difficult coalition

talks. While the nationalists may perform well enough to get some members into

the legislature, they will be excluded from coalition negotiations.

What could force Germany to take a more decisive role in the European

Union, however, would be a victory by the Euroskeptic forces in France or

Italy. If that happens, Berlin would try to preserve the bloc and reach an

understanding with the rebel governments to introduce internal reform. But the

government in Berlin would also hedge its bets by making plans with its

regional allies in the event the European Union, and euro zone do, in fact,

disintegrate.

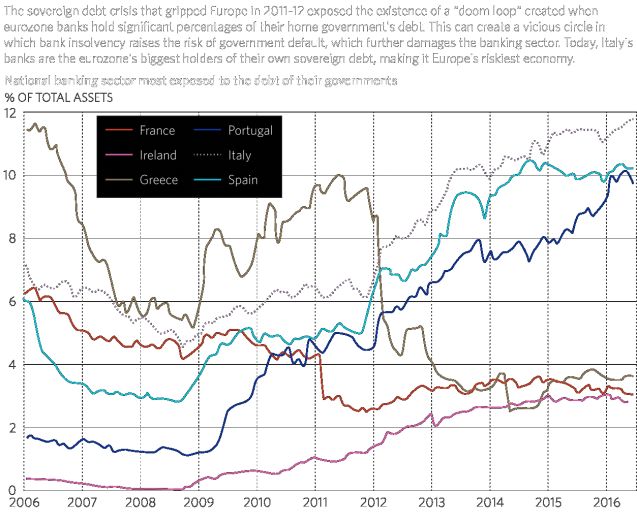

As for Italy, political uncertainty, fragile banks, low economic growth

and high debt levels will once again raise questions about the future of the

eurozone's third-largest country.

Eurozone Countries Most

Susceptible to a 'Doom Loop'

The Netherlands, one of the eurozone's wealthiest countries and an

important player in Northern Europe, will hold a general election in March. As

in other eurozone countries, Euroskeptic and anti-immigration forces there will

have a prominent role, showing that discontent with the status quo is strong.

But a streak of skepticism among Dutch voters about the European Union does not

mean it would break with the bloc.

While in the likely case, the Euroskeptics fail to access power; their

influence will still force the Dutch government to become more and more

critical of the European Union, resisting plans to deepen Continental

integration and siding with other Northern European countries in their

criticism of events in the south. If events in France and Italy bring about the

collapse of the eurozone, the Netherlands will react by continuing to work with

Germany and other Northern European countries.

Every year of the past decade has been a test of the eurozone's

resilience, but 2017 could be the year when the bloc's very survival is

endangered. France will hold presidential elections in two rounds in April and

May. Opinion polls say the National Front party, which has promised to hold a

referendum on France's membership in the eurozone, should win the first round

but be defeated in the second. The Brexit referendum and the U.S. presidential

election, however, have shown that polls sometimes fail to detect the deep

social tendencies driving populist movements.

Elsewhere, in the European periphery, the minority government of Spain

will be forced to negotiate with the opposition on legislation, leading to a

complex decision-making process and to pressures to reverse some of the reforms

that were introduced during the height of the economic crisis. Catalonia will

continue to push for its independence as its government challenges Madrid in

some instances, ignores it entirely in others, and negotiates with it when

necessary. Even if negotiations to ease frictions between Madrid and Catalonia

take place, the central government will not authorize a legal referendum on

independence, and Catalonia will not abandon its plans of holding it. Tensions

will remain high in 2017, but Catalonia will not unilaterally declare independence

this year.

In Greece, the government will continue pushing its creditors for

additional measures of debt relief, but because of the German elections, there

will be little progress on the issue. With debt relief temporarily off the

table, Athens will demand lower fiscal surplus targets and will reject

additional spending cuts. Relations between Athens and its creditors will be

tense, but there should be room for compromise. The resignation of the Greek

government is possible, albeit improbable, considering that the emergence of

opposition forces in the country makes the outcome of early elections highly

uncertain – and the government has no guarantee of retaining power.

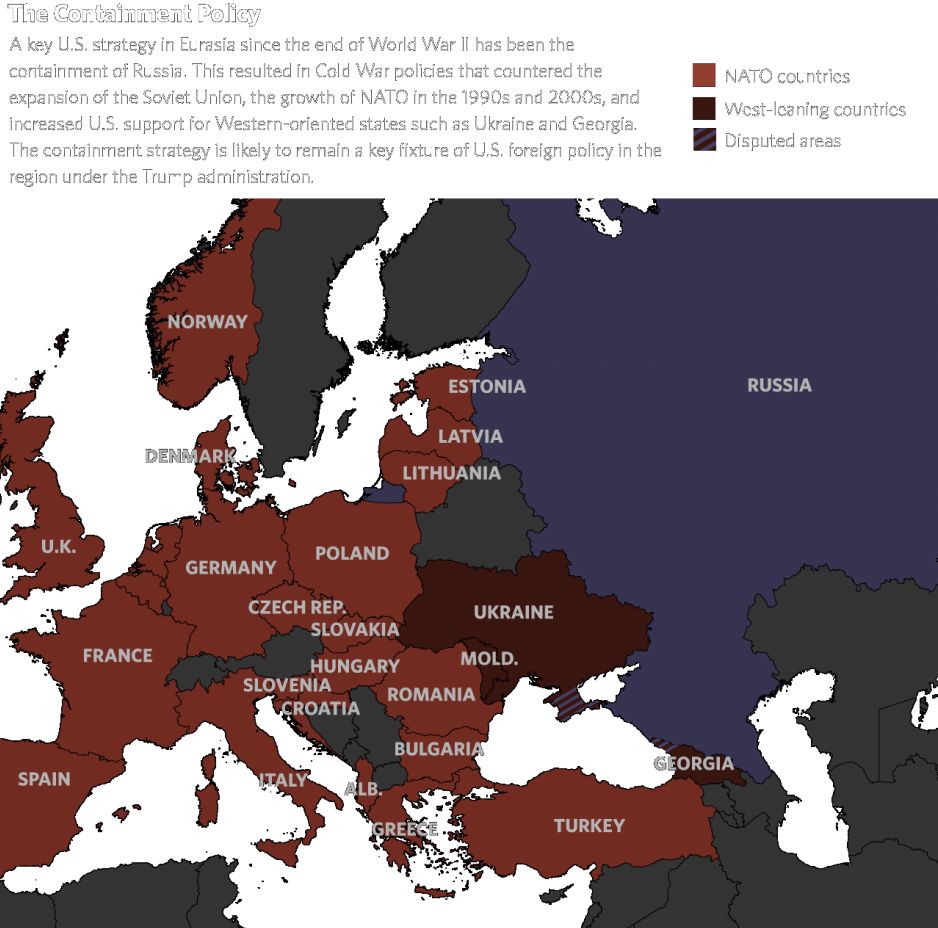

As President Donald Trump assumes office, Washington's relationship with

Moscow could change. During his campaign, Trump highlighted the need for

greater cooperation with Russia in the Syrian conflict. He also criticized the

sanctions against Russia as ineffective and bad for business. Trump has even

hinted that a bargain between Washington and Moscow could be in the making,

saying the United States might ease sanctions against Russia in exchange for a

nuclear arms reduction deal.

An Eventual Understanding on

the Brexit

In 2017, the debate in the United Kingdom will not be whether the Brexit

should happen but how it should happen. The British government will be divided

on how to approach the negotiations with the European Union, and the Parliament

will demand a greater say in the process. The issue will create a constant

threat of early elections, but even if such elections do come to pass, they

would only delay the Brexit, not derail it. The government and the Parliament

will eventually reach an understanding, however, and the United Kingdom will

formally announce its intentions to leave the European Union.

Once the negotiations begin, the United Kingdom will push for a

comprehensive trade agreement to include as many goods and services as possible

– one that would also give the country more autonomy on immigration. This would

involve either signing a free trade agreement with the European Union or agree

on Britain's membership in Europe's customs union, an area where member states

share a common external tariff. A transitional agreement to buy London more

time to negotiate a permanent settlement will probably also be part of the

discussion. London and the European Union will also negotiate the terms of the

United Kingdom's withdrawal, including its EU budget commitments and the status

of British citizens in the European Union and the status of EU citizens in the

United Kingdom. Given the magnitude of these issues, not to mention the

magnitude of the elections in France and Germany, several of the most important

decisions will be delayed until at least 2018.

Central and Eastern Europe

Countries of Central and Eastern Europe will circle the wagons to

protect themselves from what they see as potential Russian aggression – and

from the uncertainty surrounding U.S. foreign policy. Leading the charge will

be Poland, which will try to enhance political, economic and military

cooperation with its neighbors. It will also support the government in Ukraine

politically and financially and will lobby Western EU members to keep a hard

stance on Moscow by advocating the continuation of sanctions, increasing

military spending, supporting Ukraine, etc. – a position the Baltic States and

Sweden are likely to support. Unsure though Warsaw may be about the Trump

administration, the government will still try to maintain good ties with the

White House as it continues to defend a permanent NATO presence in the region.

Countries in the region may even pledge to spend more on defense.

Not all countries will react the same way to this new geopolitical

environment, of course. Hungary or Slovakia, for example, do not have the same

sense of urgency as Poland when it comes to Russia, so their participation in

pre-emptive measures could be more restrained.

Moscow's attempts to exploit divisions within the European Union will

strain German-Russian relations. Germany will try to keep sanctions against

Russia in place but will face resistance from some EU members, which would

rather lift sanctions to improve their relations with Moscow. Germany will also

defend cooperation on defense and security as a way to deal with uncertainty

about NATO and Russia. The German government will continue to support Ukraine

politically and financially, but not militarily.

In the meantime, Russia will exploit divisions within the European Union

by supporting Euroskeptic political parties across the Continent and by seeking

to cooperate with the friendlier governments in the bloc. Some countries,

including Italy, France, and Austria, will advocate improved relations with

Russia, giving Moscow a better chance to break the sanctions bloc in the union.

Some level of sanctions easing from the European Union is likely by the end of

the year.

Stopping Migration at Its

Source

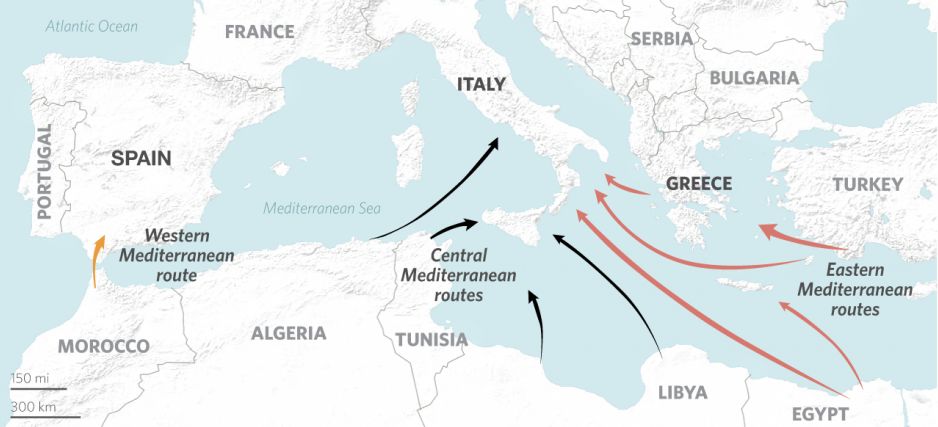

There is only so much EU member states can do to stem the flow of migrants in 2017. In the Central

Mediterranean route, Brussels will try to halt migrants from leaving Africa by

cooperating with their countries of origin and by working with the primary

transit states. But the difficulty in actually severing African migration routes

and the absence of any viable government in Libya will limit the European

Union's ability to halt the flow of peoples through the Central Mediterranean.

Central

and Eastern Mediterranean Migrant Routes

In the Eastern Mediterranean route, the European Union will keep its

line of communication with Turkey open, its political differences with Ankara

notwithstanding. European elections and internal divisions, however, will

prevent the block from giving in to many of Turkey's demands, particularly the

one that grants visa liberalization for Turkish citizens. A short window of

opportunity on the issue will open in the first months of the year, but if no

progress is made before Europe's electoral cycle begins in March in the

Netherlands, the issue will be postponed for the rest of the year. Progress on

less controversial issues such as trade and funds will be somewhat easier to

make.

The role of Russia

France, Italy, Austria and Greece will end up seeking a more balanced

relationship with Russia, while countries that tend to be more vulnerable to

its vagaries – Poland, Romania, the Baltics and Sweden – will band together to

fend off what they see as potential Russian aggression. Germany will try to

play both sides, something that will be increasingly difficult to do as it also

fights to keep the euro zone intact. Germany's distraction will, in turn,

enable Poland to emerge as a stronger leader in Eastern Europe, extending

political, economic and military support to those endangered by the West's

weakened resolve.

That is not to say that Russia will be entirely unconstrained. Though

Washington appears somewhat more willing to negotiate with Moscow on some

issues, the United States still has every reason to contain Russian expansion

so that it will maintain, through NATO, a heavy military presence on Russia's

European frontier. This is bound to impede any negotiation. Still, Russia will

use every means at its disposal – military buildups on its western borders, the

perception of its realignment with the United States, the exploitation of

European divisions – to poke, prod and ultimately bargain with the West. And in

doing so, it will intimidate its neighbors and attempt to crowd out Western

influence in its near abroad.

Even a hint of reconciliation between Moscow and Washington will echo

throughout Russia's borderlands. Russia will almost certainly maintain its

military presence in eastern Ukraine, but the United States and some European

countries will adopt a more flexible interpretation of the Minsk protocols to

justify the easing of sanctions. And because this will leave the government in

Kiev more vulnerable to Russian coercion, Ukraine can be expected to intensify

military, political and economic ties with Poland and the Baltic states.

In fact, the prospect of a U.S.-Russia reconciliation will all but halt

the efforts of otherwise pro-West countries, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia – to

integrate into Western institutions, as will the growing divisions in Europe.

These countries will not fully ally with Russia, but they will be forced to

work with Russia tactically on economic issues and to soften their stances on

pro-Russia breakaway territories.

Just as Ukraine will strengthen security efforts with Poland and the

Baltics for security, Georgia will strengthen security efforts with Azerbaijan

and Turkey. Turkey will maintain its foothold in the Caucasus and the Black

Sea, but it will also make sure to maintain energy and trade ties with Moscow,

lest it jeopardize its mission in Syria.

Russia will remain the primary arbiter in the

Nagorno-Karabakh dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan, playing the two

against each other to its advantage. And with the European Union's Eastern

Partnership and other EU-led programs likely to suffer from the bloc's

divisions and distractions, Russia will have the opportunity to deepen its

influence in the region by advancing its integration initiatives such as the

Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization.

Russia's trouble at Home

For all the opportunity Russia has abroad this coming year, it will have

perhaps even more challenges at home. Even if it pulls itself out of recession,

it still faces a prolonged period of stagnation, and the government will have

to adhere to a conservative budget until oil prices rise meaningfully again.

The Kremlin will continue to tap into its reserve funds and will rely more on

international borrowing to maintain federal spending priorities.

Russia's regional governments are even more financially vulnerable; they

will have to depend on the Kremlin or international lenders for relief. This

reliance will only add to existing tensions between the central and regional

governments, tensions that will compel the Kremlin to tighten and centralize

its control.

What economic relief does come the federal government's way will not

trickle down to the Russian people, who will continue to bear the brunt of the

recession. Protests will take place sporadically throughout the year, and the

Kremlin will respond by clamping down on unrest through its security apparatus

and more stringent legislation. The Kremlin will, however, increase spending on

some social programs later in the year ahead of the 2018 presidential election.

As the government becomes more authoritarian, power struggles among the

security forces, liberal circles, energy firms and regional governments are

bound to ensue. President Vladimir Putin will try to curb the power of his

potential challengers, particularly Rosneft chief Igor Sechin and his loyalists

in the Federal Security Service, through various institutional reorganizations.

Restructuring, of course, will entail occasional purges and appointments of

loyalists, the ultimate purpose of which is to consolidate power under Putin.

His grabs for power, however, will isolate him, and in his isolation, he will

have fewer and fewer allies.

Making America Great again?

We have all read the stories about President-elect Donald Trump making

America great again and bringing

back jobs to the US.

But what is to come one could also argue are the political

manifestations of much deeper forces in play. In much of the developed world,

the trend of aging demographics and declining productivity is layered with

technological innovation and the labor displacement that comes with it. China's

economic slowdown and its ongoing evolution compound this dynamic. At the same

time, the world is trying to cope with reduced Chinese demand after decades of

record growth; China is also slowly but surely moving its economy up the value

chain to produce and assemble many of the inputs it once imported, with the

intent of increasingly selling to itself. All these forces combined will have a

dramatic and enduring impact on the global economy and ultimately on the shape

of the international system for decades to come.

These long-arching trends tend to quietly build over decades and then

noisily surface as the politics catch up. The longer economic pain persists the

stronger the political response.

Also, the global superpower is not feeling all that super. In fact, it's

tired. It was roused in 2001 by a devastating attack on its soil, it

overextended itself in wars in the Islamic world, and it now wants to get back

to repairing things at home. Indeed, the main theme of U.S. President-elect

Donald Trump's campaign was retrenchment, the idea that the United States will

pull back from overseas obligations, get others to carry more of the weight of

their defense, and let the United States focus on boosting economic

competitiveness.

Barack Obama already set this trend in motion, of course. Under his

presidency, the United States exercised extreme restraint in the Middle East

while trying to focus on longer-term challenges, a strategy that, at times,

worked to Obama's detriment, as evidenced by the rise of the Islamic State. The

main difference between the Obama doctrine and the beginnings of the Trump

doctrine is that Obama still believed in collective security and trade as

mechanisms to maintain global order; Trump believes the institutions that

govern international relations are at best flawed and at worst constrictive of

U.S. interests.

No matter the approach, retrenchment is easier said than done for a

global superpower.

Revising trade relationships the way Washington intends to, for example,

may have been feasible a couple of decades ago. But that is no longer tenable

in the current and evolving global order where technological advancements in

manufacturing are proceeding apace and where economies, large and small, have

been tightly interlocked in global supply chains. This means that the United

States is not going to be able to make sweeping and sudden changes to the North

American Free Trade Agreement. In fact, even if the trade deal is renegotiated,

North America will still have tighter trade relations in the long term.

The United States will, however, have more space to selectively impose

trade barriers with China, particularly in the metals sector. And the risk of a

rising trade spat with Beijing will reverberate far and wide. Washington's

willingness to question the "One China" policy – something it did to

extract trade concessions from China – will come at a cost: Beijing will pull

its trade and security levers that will inevitably draw the United States into

the Pacific theater.

But the timing isn't right for a trade dispute. Trump would rather focus

on matters at home, and Chinese President Xi Jinping would rather focus on

consolidating political power ahead of the 19th Party Congress. And so economic

stability will take priority over reform and restructuring. This means Beijing

will expand credit and state-led investment, even if those tools are growing

duller and raising China's corporate debt levels to dangerous heights.

Tightening monetary policy in the United States and a strong U.S. dollar

will shake the global economy in the early part of 2017. The countries most

affected will be those in the emerging markets with high dollar-denominated

debt exposure. That list includes Venezuela, Turkey, South Africa, Nigeria,

Egypt, Chile, Brazil, Colombia and Indonesia. Downward pressure on the yuan and

steadily declining foreign exchange reserves will meanwhile compel China to

increase controls over capital outflows.

The United States is pulling away from its global trade initiatives

while the United Kingdom, a major free trade advocate, is losing influence in

an increasingly protectionist Europe. Global trade growth will likely remain

strained overall, but export-dependent countries such as China and Mexico will

also be more motivated to protect their relationships with suppliers and seek

out additional markets. Larger trade deals will continue to be replaced by

smaller, less ambitious deals negotiated between countries and blocs. After

all, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and the Trans-Pacific

Partnership were themselves fragments spun from the breakdown of the Doha Round

of the World Trade Organization.

South Asia

As in so many other regions, nationalism is on the rise in South Asia,

and leaders there will use it to advance their political agendas. This will be

particularly pronounced as India and Pakistan prepare for elections.

Plus Pakistan's military will use the threat of India as an excuse to

maintain the status quo in its civil-military balance of power.

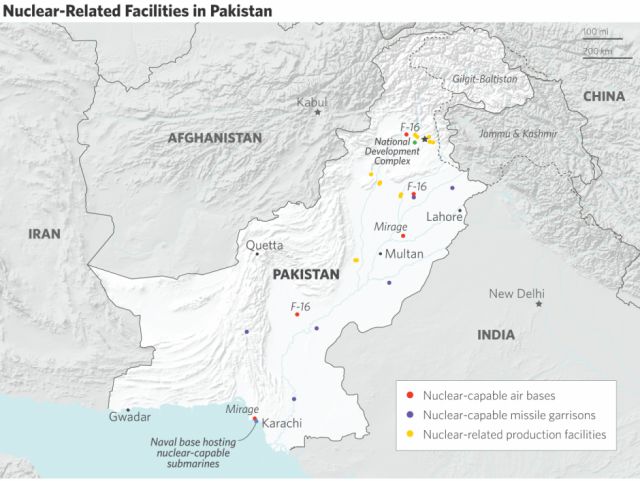

Unable to match India's massive military expenditures, Pakistan has

taken an asymmetric approach to compensate for its comparative weakness:

Building up its nuclear arsenal. In fact, Islamabad has already begun to design

and develop tactical nuclear weapons that could someday be deployed against

Indian troops on the battlefield. Now Pakistan is searching for the

second-strike capability, the means of threatening nuclear retaliation even

after having suffered an overwhelming nuclear strike.

2017 will be a crucible for Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). In 2014, the BJP became the first party in 30 years to win a majority

in the lower house of parliament, at once dispelling, if only temporarily, the

tradition of a coalition government that has long defined Indian politics. But

even with such a mandate, honoring promises of reform in a legislature as

fractured and convoluted as India's is difficult, prone

to slow, uneven progress.

Now, the great challenge facing the BJP is to continue making progress

on its promises and to streamline the country's onerous land, labor and tax

regulations, all in support of unleashing the labor-intensive economic growth

India needs to absorb the 12 million people who enter the job market every

year. This is no easy task. The sheer scale of reform in a stratified,

billion-citizen democracy such as India is so immense that its implementation

is measured not in years but generations. And so Modi has taken the long view,

having used his first five-year term to lay the groundwork for a second term in

2019.

To that end, Modi means to win state-level elections to bolster his

party's numbers in the upper house of parliament; doing so, of course, would

make it easier to pass legislation. The elections in Uttar Pradesh, India's

most populous and electorally most important state, are particularly important.

A victory there would substantially bolster the BJP's numbers in the upper

house and go a long way toward securing a presidential re-election in 2019.

The outcome of the election is less important than the strategy the BJP

employed to win it. This is because the three remaining bills of the Goods and

Services Tax (GST) failed to pass during the winter session of parliament. The

opposition capitalized on the ill will be generated by Modi's demonetization

campaign against black money (the measure entailed the withdrawal of 500 and

1,000 rupee notes from circulation). Modi expected this, of course, but he went

through with the measure anyway as part of a bigger political calculation: He

wanted to hone his image as a pro-poor, anti-corruption candidate ahead of the

Uttar Pradesh elections.

Failing to pass all of the bills in 2016 means that the BJP will have to

push back its April 1 deadline for implementing them and focus on passing the

remaining ones in 2017. Other reforms will, therefore, have to be put on hold.

Moreover, given that demonetization is a necessarily disruptive process for a

cash-based, consumption-driven economy such as India's, growth will slow in

2017. In turn, this will lower inflation rates and compel the Reserve Bank of

India to loosen monetary policy.

The rise of the BJP also gave rise to nationalism, a trend that will

continue throughout 2017. Its renaissance will force the BJP to take a hard

line against Pakistan, but this, too, is at least partly a political

calculation: Opposition to Pakistan cuts across party lines, so admonishing

Islamabad will make it easier for the BJP to keep an otherwise fractious voting

base intact.

August 2017 will mark the 70th anniversary of India and Pakistan's

independence, so nationalism in each country will be running high. This uptick

in nationalism, not to mention the perennial cross-border militant attacks into

Kashmir, will have governments on both sides

of the border on high alert. And even though the newest evolution of India's

military doctrine, which is more tactical and precise than its forebear, will

deter attacks and minimize the risk of escalation, it will not remove the

possibility entirely.

Pakistan's Government Remains

Steadfast

Underlying the dynamics of the region is how much power Pakistan's

military, and particularly the army, has in the

country's politics. It has ruled for nearly half of the country's 69-year

history. It is too early to say how Gen. Qamar Bajwa, the country's recently

appointed army chief, will alter the civil-military balance of power. But it is

clear that the threat from India, real or perceived, will push the army to

maintain the status quo, even in light of two milestones recently passed on the

way to civilian rule: the completion of a democratically elected president's

five-year term in 2013, and the abdication of power by an army chief after one

three-year term in 2015.

Either way, the Pakistani government will remain steadfast in its role

in the Afghan conflict, which is to say, Islamabad will obstruct talks, if it

allows them to emerge at all if it feels as though it is being sidelined by

Afghanistan or by the United States. But what also stands in the way of

resolution are the divisions within the Taliban, manifested most notably this

year by its Doha faction, which began vocalizing calls for the Taliban to

transition from an insurgency into a viable political movement – divisions that

will become all the more apparent in 2017. Instability will hamper progress on

transnational energy projects such as the

Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India pipeline, which highlight the country's

role as an energy bridge linking energy abundant Central Asia with energy

deficient South Asia.

A New Strategy in the South

China Sea

Things are changing in the South China Sea. In its waters, China's influence has steadily grown in recent years,

thanks to a campaign meant to expand and modernize the Chinese military

and to develop the sea's islands. In 2016, however, the pace of expansion

appeared to slow somewhat. In part, the slowdown was due to the in the above

link mentioned international court of arbitration's ruling against China's

maritime territorial claims. But it was also due to the fact that China, having

achieved many of its goals in the South China Sea, is now replacing a strategy

of aggressive expansion with a strategy that, in addition to coercion, leaves

some room for cooperation. In fact, Beijing has increasingly sought to

cooperate with potentially amenable claimants, such as Malaysia and the

Philippines, by making conciliatory gestures on economic and maritime issues.

At the same time, Beijing has continued to press more outspoken critics of its

regional claims through limited punitive economic measures and other

confrontational actions.

China will try to maintain this strategy in 2017. To that end, it will

prefer to handle disputes on a strictly bilateral basis, and it will likely

extend concessions to areas such as energy development and potentially sign a

code of conduct that limits its actions.

And though this strategy eased maritime tensions somewhat in 2016, it

may have more mixed results in 2017. Challenging its success will be a strained

relationship with the United States, Vietnam's continued ventures into maritime

construction activities, and the entry of countries such as Indonesia,

Singapore, Australia and Japan – none of them claimants to the South China

Sea's most hotly contested waters – into regional maritime security affairs.

Beijing will be particularly concerned about Japan, which will expand

economic and maritime security cooperation with key South China Sea claimants.

(Tokyo

may also work more closely with the United States in the South

China Sea and the East China Sea.) Beijing may try to counter U.S.-Japanese

cooperation by imposing an air defense identification zone, which would, in

theory, extend Chinese control over civilian aircraft in the South China Sea,

though doing so would threaten China's Southeast Asian relationships. And

though China would probably prefer to be as conciliatory as it can as the

situation warrants, heightened great power competition in the Asia-Pacific may

compel it otherwise. The more Japan is involved, the more China will have to

balance, with different degrees of success, its relationships and its interests

with members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Japan's Pride of Place

Greater involvement in the South China Sea, however, is just one piece

of the Japanese puzzle. In the two decades following

the end of the Cold War, Japan found

itself strategically adrift. Today, buffeted by demographic decline,

China's rise and a growing recognition across the Japanese political spectrum

that change is necessary, Tokyo is in the early stages of reviving Japan's

economic vitality and military power, and reclaiming its pride of place in the

region.

In 2017, the administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will make

notable progress in that regard. In addition to expanded involvement in the

South and East China seas, the Abe administration is likely to ramp up Japan's

diplomatic and economic outreach in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, Abe will pursue

a peace treaty with Russia over longstanding territorial disputes. (Even

without a formal treaty, the two countries will deepen bilateral trade and

investment.) Above all, Japan will expand bilateral diplomatic and security

cooperation with the United States, seeking to ensure Washington's commitment

and involvement in the region. At the same time, Japan will take advantage of

opportunities opened by potential changes to the United States' regional

strategy – namely, a shift from multilateral partnerships like the failed

Trans-Pacific Partnership to bilateral relationships – to play a more active

leadership role to constrain China.

Abe will use his strong political position – the ruling coalition has

supermajorities in both houses of the Japanese parliament – to press his agenda

at home. In 2017, Abe will do what he can to maintain the first two 'arrows' of

his economic plan — monetary easing and fiscal stimulus — while pushing forward

with structural reforms (the third arrow) in areas such as labor, women's

workforce participation, and immigration. His administration may also seek to

capitalize on heightened regional security competition and uncertainty over

Washington's regional position to press for constitutional reforms meant to

normalize Japan's military forces.

For updates

click homepage here