No doubt to rattle the international markets (the price of oil shot up

yesterday) several more times soon, Iran threatend

to block Strait of Hormuz oil route.

The last few weeks have seen the latest round of a cycle that has played

out repeatedly over the last several years: Israel escalates claims that Iran

is close to attaining a bomb that could threaten the existence of the Jewish

state. The United States and Europe then propose hardened sanctions aimed at

deterring that activity -- while Washington makes sure to note that military

options remain on the table -- and Iran responds by threatening to disrupt the

shipment of oil through the Strait of Hormuz, enervating global energy markets.

The rhetoric in this circumstance belies the actors' capabilities. Israel knows

it has limited ability to launch a successful airstrike on Iran, while the

United States wants to avoid a new war with a Persian Gulf state, and Tehran

does not want to incur the economic cost of shutting down the Strait of Hormuz

yet does threaten it would proceed.

Not only does Iran’s most reliable trading partner

China receive 40% of its oil via the Strait (so China would prevent it trough backchannels) there are also other reasons Iran

won't do it anytime soon.

Closing the strait,

while I have referred to it before, is not nearly as easy as

Adm. Habibollah Sayari, commander of the Iranian

Navy, would have it.

Admiral Habibollah

Sayari says Iran could easily close the Strait of Hormuz

Iran tried this before and failed miserably. In 1984, during the

Iran-Iraq War, Saddam Hussein attacked Iranian oil tankers and the Iranian

oil-processing facility at Kharq Island. Iran struck

back by attacking Kuwaiti tankers carrying Iraqi crude and then other tankers

in the Persian Gulf. In 1987, after years of growing disruptions in this vital

waterway, President Ronald Reagan responded by offering to reflag Kuwaiti tankers

with the U.S. flag and provide U.S. naval escort. Iran shied away from direct

attacks on U.S. warships but continued sowing mines, staging attacks with small

patrol boats, and firing a variety of missiles at tankers.

On April 14, 1988, the guided-missile frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts

struck an Iranian mine; no sailors were killed but several were injured and the

ship nearly sank. The U.S. Navy responded by launching Operation Praying

Mantis, its biggest surface combat action since World War II.

Half a dozen U.S. warships in two separate Surface Action Groups moved

in to destroy two Iranian oil platforms. The Iranians responded by sending

armed speedboats, frigates and F-4 aircraft to fire at the U.S. warships.

In defending themselves, the American vessels sank at least three

Iranian speedboats, one gunboat and one frigate; other Iranian ships and

aircraft were damaged. The only major U.S. loss occurred when a Marine Corps

Sea Cobra helicopter crashed, apparently by accident, killing two crewmen.

The war all but ended less than three months later when the guided

missile cruiser USS Vincennes mistakenly fired a surface-to-air missile at an

Iranian passenger airliner that it had mistaken for a fighter jet. The plane

was destroyed and 290 people killed. Although this was an accident, the Iranian

regime was convinced that Washington was escalating the conflict and decided to

reach a truce with Iraq.

The greatest loss suffered by U.S. forces during this whole conflict

occurred in 1987 when an Iraqi aircraft fired an Exocet missile that hit the

frigate USS Stark, killing 37 sailors and injuring 21. (Saddam Hussein claimed

this was an accident.)

The Iranians had little to show for their efforts: Lloyd's of London

estimated that the Tanker War resulted in damage to 546 commercial vessels and

the deaths of 430 civilian mariners but many of those losses were caused by

Iraq, not Iran. While these attacks temporarily disrupted the free passage of

oil, they did not come close to closing the strait.

Despite the unveiling of a new antiship cruise missile called the Qader,

Iran's conventional naval and air forces—on display during the Veleyat 90 naval exercises in the Persian Gulf which ended

Monday— are still no match for the U.S. and its allies in the region. The U.S.

alone has in the area two carrier strike groups, an expeditionary strike force

(centered around an amphibious assault ship that is in essence a small aircraft

carrier), and numerous land-based aircraft at bases such as Al Udied in Qatar, Al Dafra in the

United Arab Emirates, and Isa Air Base in Bahrain. The U.S. and our Arab allies

(which are equipped with a growing array of modern American-made equipment such

as F-15s and F-16s) could use overwhelming force to destroy Iran's conventional

naval forces in very short order.

Iran's real ability to disrupt the flow of oil lies in its asymmetric

war-fighting capacity. Iran has thousands of mines(and any ship that can carry

a mine is by definition a mine-layer), a small number of midget submarines,

thousands of small watercraft that could be used in swarm attacks, and antiship

cruise missiles. If the Iranians lay mines, it will take a significant amount

of time to clear them. It took several months to clear all mines after the

Tanker War, but a much shorter period to clear safe passages through the

Persian Gulf to and from oil shipping terminals.

Antiship cruise missiles are mobile, yet those can also be found and

destroyed. Yono submarines are short-duration threats, they eventually have to

come to port for resupply, and when they do they will be sitting ducks. U.S.

forces may take losses, as they did with the hits on the USS Stark and Samuel

B. Roberts, but they will prevail and in fairly short order.

The Iranians must realize that the balance of forces does not lie in

their favor. By initiating hostilities they risk American retaliation against

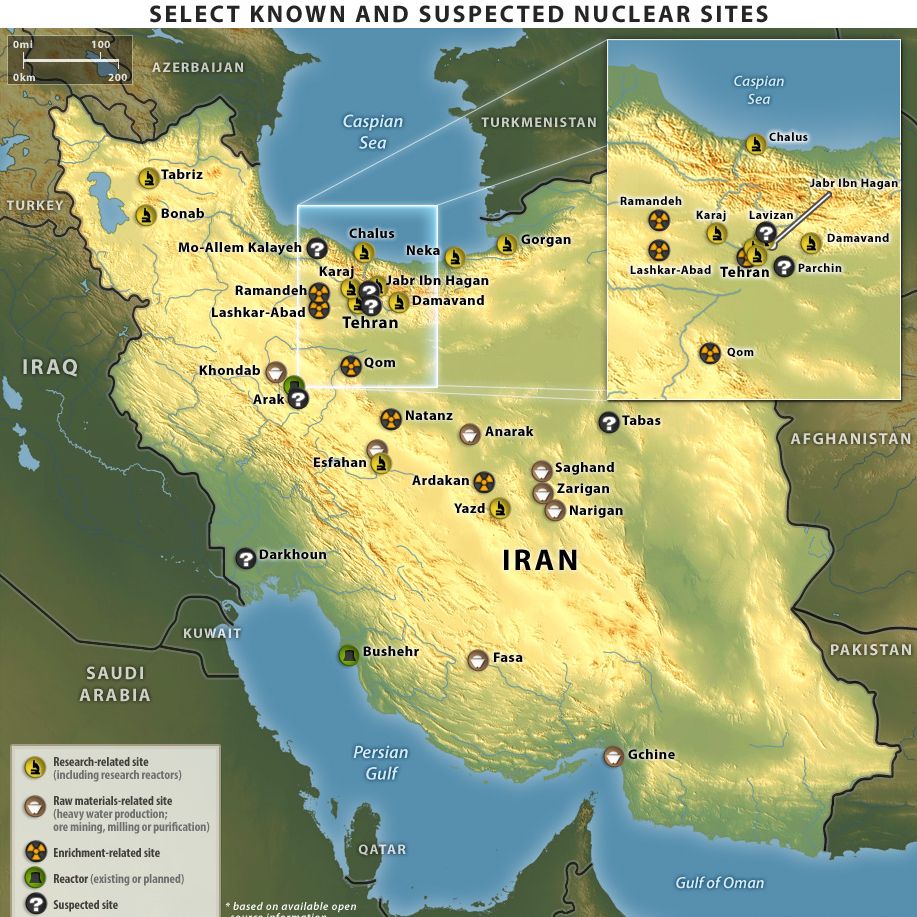

their most prized assets, their covert nuclear-weapons program. The odds are

good, then, that the Iranians will not follow through on their saber-rattling

threats.

But this heated rhetoric does suggest how worried the Iranians are about

the potential impact of fresh sanctions on

their oil industry.

Conclusion: Iran has mastered the art of

crisis escalation and de-escalation. In this way, the regime in Tehran

resembles North Korea, which has deliberately cultivated a perception of

unpredictability and, despite crushing sanctions, has kept itself at the center

of the international agenda of most of the world’s top powers for more than a

decade. Through its cycle of escalating and de-escalating threats, Iran thus

expects it will continue reminding the world of its leverage over the

geopolitically sensitive Strait of Hormuz.

Tehran could not keep the straits closed for long -- perhaps no more

than a handful of days -- but that alone would still temporarily block shipment

of a fifth of all traded global oil, sending prices rocketing and severely

denting hopes of global economic recovery. But such action would swiftly

trigger retaliation from the United States and others that could leave the

Islamic republic militarily and economically crippled. The true purpose of its

recent saber-rattling, many analysts suspect, may be more a mixture of

deterring foreign powers from new sanctions and distracting voters from rising

domestic woes ahead of legislative elections in March. The real risk remains

that in playing largely to domestic audiences, policymakers in Washington, Tel

Aviv and Tehran inadvertently spark something much worse than they ever

intended.

The most likely outcome however is that next month rhetoric will be

cooling again and U.S. sanctions will start to leave space for allies of the

United States to continue buying Iranian crude (albeit at reduced levels). In

fact Washington and Europe might reach out to Iran once again for a diplomatic

dialogue thereby sideling Israel.

For updates click homepage

here