By Eric Vandenbroeck

Mawlamyine, known as Moulmein

by the British, was the first capital of British Burma until 1852 after they

took control of the area following the First Anglo-Burmese War. Today, it’s the

third largest city in the country after Yangon and Mandalay and known for its

good food. Even more so than Rangoon, Moulmein still captures the essence of

the nineteenth-century plural society – just as it also retains a rich

collection of colonial-era buildings. It is also known for its association with

British writers Rudyard Kipling and George Orwell.

Born Eric Blair, Orwell’s maternal grandmother lived here, and he moved

to Moulmein in April of 1926 and stayed for less than a year before being

transferred to Katha in Upper Burma. Orwell kept to himself during much of his

time in Burma, but his affinity for the people and the culture is clear as he

learned Burmese and was said to be fluent before he left. He also acquired some

native tattoos consisting of little, blue circles on his knuckles which, as

stated previously, many Burmese in rural areas believed were helpful in

protecting against bullets and snake bites. Unfortunately, they weren’t all

that helpful in preventing disease. Orwell's diagnosis of tuberculosis in

December 1947 signaled the downward spiral of his health. His Burmese

experiences played heavily in his early works such as the novel Burmese Days

and the essays “A Hanging” and “Shooting an Elephant.”

Mawlamyine also made a deep impression on writer Rudyard Kipling

twenty-seven years earlier when he passed through in 1899. What he saw inspired

him to try and translate that vision to the rest of the world in his poem

Mandalay. He wrote in more detail in letters to friends. In one, he describes

his first impression of the town:

Moulmein is situated up the mouth of a river which ought to flow through

South America, and all manner of dissolute native craft appear to make the

place their home… Visitors are rare in Moulmein – so rare that few but

cargo-boats think it worth their while to come off from the shore. Strictly in

confidence I will tell you that Moulmein is not a city of this earth at all.

Sindbad the Sailor visited it, if you recollect, on that memorable voyage when

he discovered the burial-ground of the elephants. Kipling described it as, “a sleepy town,

just one house thick, scattered along a lovely stream and inhabited by slow,

solemn elephants, building stockades for their own diversion. There was a

strong scent of freshly sawn teak in the air.”

Today, Mawlamyine is still situated on that river, still visited by

native boats, and to my eye, the river still moves with a slow, muddy current

that would look perfectly at home in South America.

Mawlamyine

native river boats

However, I didn’t see any elephants or smell freshly-cut teak. It is a

city alive with trucks and motorcycles, humming with activity and eagerly

awaiting the economic changes that have been promised.

The place is a beehive of ceaseless activity, typically of most Asian

markets.

Mawlamyine seems to have less grit and more charm than my last stop at Hpa-An. However, this area has seen its fair share of

conflict and trouble during the decades the Burmese military has kept the

people under its thumb.

Although lacking the international press coverage of the government’s

conflicts with the Karen and the Kachin tribes, the Mon insurgency was a

concern here just a few short years ago. Several organizations representing the

Mon people have been formed from 1952 to 1996, and some of them have waged war

against the government attacking police stations and carrying out bombings over

the years. Burmese government troops captured the Mon National Liberation Army

(MNLA) headquarters in Thailand in 1990, but fighting continued in outlying

areas. Government and New Mon State Party (NMSP) representatives began

negotiations in Mawlamyine in December of 1993 and signed a ceasefire agreement

in June of 1995. At least 12,000 refugees fled to Thailand during the ongoing conflict.

The last bombings took place in Mawlamyine in May of 2009, and a peace

agreement was signed here in February of 2012.

Unlike the Karen, the Mon did not play a significant role in assisting

British officers operating behind enemy lines in Burma during the war.

During the war, the Japanese, who had assisted the formation of the

Burma Independence Army (BIA), granted a national independence with Ba Maw in

charge of the Burmese cabinet. It was to be a dictatorship along fashionable

fascist lines. The slogan of the new army under Aung San at the time was

"One Blood, One Voice, One Command" (ta-pyi,ta-than,

ta-meint), still today the de facto slogan of the

Burmese military. Ba Maw ‘s regime outlawed the teaching of all minority

languages.

After 1962-63, General Ne Win regime's suppression of non-Burman

cultural and political identities, epitomized by the banning of minority

languages from state schools, drove a new wave of disaffected ethnic minority

citizens into rebellion.

Shortly after seizing power in 1962, Ne Win denied the need for a

separate Mon culture and ethnicity. According to Ne Win, "the Mon

tradition had been fully incorporated into Burmese national culture, and thus

required no distinct expression.” (Emmanuel Guillon The Mons: A Civilization of

Southeast Asia, 1999, p.213).

In August 1991, the then-SLORC chairman, General Saw Maung, made a

similar speech, in which he denied the need for a separate Mon identity. (An

extract from this speech is quoted in Mikael Gravers, Nationalism as Political

Paranoia in Burma: An Essay on the Historical Practice of Power, 1996, p.240.)

Since the 1970s, many thousands of displaced Mon villagers have voted

with their feet, seeking refuge in the insurgent-controlled “liberated zones”

(and later, refugee camps) along the Thailand-Burma border.

Approximately 6,000 Mon refugees living in the camps on Thailand-Burma

border were forcibly repatriated to Halockhani camp

in Burma in 1996, despite the appeals from the Mon National Relief Committee

and the Mon Refugee Committee. Next the Myanmar Army

attacked Halockhani a

few months later, forcing a large number of refugees back to Thailand.

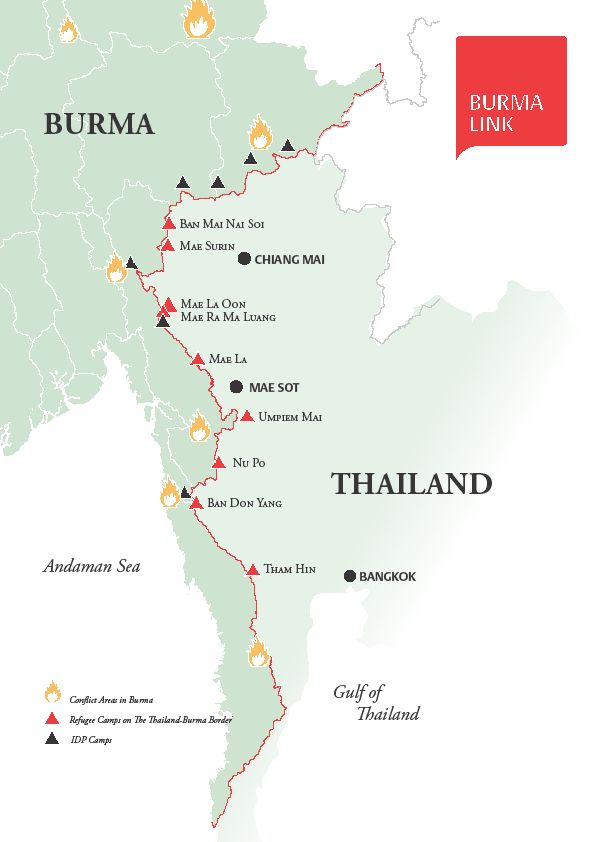

Consisting of all ethnic groups that are in collision with the Myanmar

Government currently there are roughly 150,000 Burmese refugees in nine

official camps on the Thai-Burma border, and more than two million Burmese

migrants residing primarily in urban areas of Thailand. Refugee camps are hardly

natural places to live.

Forced migrants also have largely been excluded from peace process

negotiations, or broader political discussions.

Tomorrow we will travel by bus towards the Thai Border and enter via Mae

Sot in the evening.

We will also pass near the area where, led by two children, a Karen

splinter group called “God's Army” emerged in the aftermath of the 1997

operation Spirit King offensive when the Burmese army (about 100,000 men) moved

in to swamp the route of a multi-million pound gas pipeline and clear thousands

of people before them. A hundred thousand Karen fled to refugee camps across

the Thai border.

The bizarre story of the two boys began sometime in 1997 when Burmese

troops came to their village as part of a military sweep through Karen

territory related to securing the route of an oil pipeline. When the Burmese

army attacked, the twin nine-year-olds rallied defenders of their village by

shouting “God's Army!” and leading them to victory over the Burmese soldiers.

Soon there were stories that the boys possessed magical powers, including the

invulnerability to bullets and landmines.

Later, Luther Thoo recalled that the boys did

what was necessary.

“We had to defend ourselves because we didn't like anyone to hurt us. We

love our motherland, so we chose to fight. We got seven rifles from the KNU and

there were seven of us. We used them to fight against the Burmese army. We

prayed before we fought, and then we won.”

To put this “defend ourselves” in a possible perspective; taken some

years later when the same type of attacks were still going on, underneath two

satellite photos, showing the disappearance of villages and a buildup of army

camps. Left, the same village on May 5, 2004, on the right, Feb. 23, 2007, with

all structures removed.

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) sayd high resolution satellite photos show evidence of

destroyed villages, forced relocations and a growing military presence in 25

sites across Karen state and surrounding areas. Project director Lars Bromley

said the non-profit group looked at photos taken before and after reported

attacks on ethnic minorities. He said 18 villages had almost entirely

disappeared. Others had appeared near a military camp in what researchers

concluded was a forced relocation.

The AAAS Geospatial Technologies and Human Rights Project conducted

analyses of satellite imagery in 2007 and 2009 to corroborate reports of

attacks on villages in Karen State, Shan State, and Thailand that were carried

out by the ruling military junta. Within the areas of imagery analyzed in 2007,

the bulk of the sites (18) were removed villages or villages with removed

structures, with other sites including military camps (4), possible forcibly

relocated villages (2), and one refugee camp on the Thai border. A follow-up

analysis conducted in 2009 found further evidence of destruction at 25 of the

49 locations examined.

The stronghold for the God’s Army was a jungle camp in Ka Mar Pa Law,

Myanmar, an isolated area on “God’s Mountain” reached by an 11-hour trek from

the nearest town in Thailand. The village was made up some ramshackle huts.

There was no electricity or running water.

God’s Army members were subject to strict rules of behavior including

abstinence from sex, alcohol, milk, eggs and pork. Church services were held at

least once a day.

Johnny, left,

and Luther Htoo, age 12

October 1999, the group numbered about 150 armed men. That month God’s

Army first came to people’s attention when they took in a group that called

themselves the Vigorous Burmese Student Warriors, who had stormed the Burmese

Embassy on Bangkok and took 26 people hostage. Since the thwarted 1990

elections in Burma, former student radicals had fled the country into

neighboring Thailand. In August 1999, the VBSW formed as a branch organization

opposed to the strategy of peaceful protest of the All Burma Students

Democratic Front. On October 1, 1999, a group of five members raided the

Burmese consulate in Bangkok and took 89 people hostage. The group demanded

that negotiations be opened between the National League for Democracy and the

Burmese government, and that a Parliament be convened based on the results of

the 1990 election. However, they soon relaxed their demands and began to let

the hostages go, and the Thai government eventually allowed the VBSW members to

flee by helicopter to the border with Burma.

The action provoked the Burma Army into concentrating its fire on the Ka

Mar Pa Law base. Now things started to go sour for the boys. Angered by the

embassy siege (and hoping to dislodge “God's Army' in order to exploit local

hardwood stands), in early January 2000 the Burmese Ninth Division together with Thai armed forces started to shell the Karen

rebel village, killing a number of fighters and civilian followers.

Shambles turned to disaster when ten desperados from Kamarplaw

crossed into Thailand towards Ratchaburi Hospital. By Luther's account, student

warriors and some members of God's Army went to the hospital to ask for

medicine and doctors to help people wounded by the shelling. It is not exactly

clear what happened at that point but they ended up occupying the Ratchaburi

Hospital. They demanded an end to Thai military shelling of their camp and

medical treatment for their colleagues and villagers.

At dawn, six truckloads of elite Thai commandos stormed the hospital,

ending the 22-hour standoff there, killing all 10 of the insurgents, who were

aged from teenagers to men in their thirties. Their bodies were displayed

proudly by Thai authorities, who said they had been killed after a one-hour

fire fight. Miraculously, none of the hostages were killed or hurt.

Afterwards, several of the hostages described the insurgents as “armed

men with soft hearts.” They said the hostage-takers had given up and were

killed by the Thai security forces after they surrendered. One hospital worker

told the Bangkok Post, the insurgents “were shot in the head

after they had been told to undress and kneel down.” Photographs of the dead

men showed them with their hands tied and gunshot wounds in the back of their

heads. This hardly fit the description of men killed in a gun battle. There

also weren’t many bullets in the building.

As recent as July, up until a

few weeks ago, there

was still fighting by Democratic Karen Buddhist Army - Brigade 5.

Democratic Karen Buddhist Army - Brigade 5, is an armed insurgent group

in Myanmar. The group is led by Bo Nat Khann Mway,

also known as Saw Lah Pwe, and split from the

original Democratic Karen Buddhist Army in 2010. The group is loosely

affiliated with the Karen National Union and the Karen National Liberation Army

(KNLA) which sees itself as representing all Karen people of Burma.

Mawlamyine itself is a

peaceful place today.

Moulmein is still laid out just as the colonial-era plural society

demanded. Around the main market, along the banks of the river where the

jetties protruded, remain the principal immigrant trading communities. These

are predominantly Chinese, plus the many peoples who came from South Asia,

still numbering some eighty thousand, I am told. They mainly occupy the north

end of Lower Main Road, close to the market. Here are the mosques, including

the biggest, the Kaladan, built in grey-green brick and dating from 1846. A few

buildings further south towards the market is the smaller Moghul Shia mosque.

For the non-Muslim South Asian community, there are about fifty temples,

and these all advertise themselves as catering to the faithful from the various

individual regions where immigrants originated.

Finally, today, the United Nationalities Alliance (UNA), composed of

eight ethnic political parties had a meeting in Yangon. I've been told by a

participant over the phone that that it seems they agree that a government’s

peace convention, scheduled to start on 12 January, will fail as it is unlikely

to lead to a genuine democratic federal union for the country. The United

Nationalities Alliance won

the largest number of seats in Kachin State.

Postscript 31 December 2015

Coming near the end of this particular investigation in conclusion I

like to return to my earlier question.

What can we learn from

Myanmar?

Myanmar is unique and not easily comparable to other states. Its

historical experiences preclude simplistic transference of its lessons abroad.

It presents an array of issues that, considered in comparative focus, may help

us understand not only Burma/Myanmar but other states that face a set of

similar (albeit not identical) dilemmas. Indeed, it has much to teach us about

intractable social and political problems throughout the world. Such inquiries

may also contribute to our theoretical understanding of a number of those

conundrums that bedevil other states. Internal conditions in Myanmar as well as

foreign responses to them may provide lessons about the efficacy of such

approaches in and to other countries.

Myanmar features many of the problems that face multicultural States and

raises a basic question: how might societies with many disparate ethnic and

linguistic groups achieve national integration without destroying local

cultures – creating nations and not just states. Should there be a uniform

state school curriculum in the national language, or can other local languages

be taught (see Switzerland for example), and if so at what levels?

Civil-military relations are also an issue in many developing states, and in

Myanmar the Burmese military has retained effective power since 1962.-certainly

one of the longest such reigns in the modern era. Political and social

pluralism is important in many societies, and Myanmar may offer lessons on the

effect of the presence or absence of various components of civil society on its

people and the political process. We could draw from Myanmar’s sad experience

with economic development how better to encourage equitable and sustained

growth that spreads across a diverse population. The military's opening to

foreign investment and the expansion of the local private sector have not met

economic expectations, and one might ask how rent-seeking and corruption

affected the attempt to reform a rigid socialist system.

We should question how international and indigenous political legitimacy

symbols and attitudes may differ and may be perceived, and what effect these

views have on hot' internal and external state actors. What does it take in

Myanmar for a government to be considered legitimate by its various peoples and

the international community?

We need to know what kinds of foreign policies toward Myanmar have

proven to be effective or ineffective. International organizations can learn

valuable human rights lessons from the Burmese situation that will help the

international community-individual states, international institutions such as

the United Nations or ASEAN, and international nongovernmental

organizations-improve conditions there. The Myanmar case may help us understand

whether the international community can effectively promote democracy, pluralism,

and better governance elsewhere, and if so, over what period and to what

extent.

Will there be peace between the government and the many ethnic groups?

Will they be able to maintain their culture in the midst of a tsunami of new

development and influence? The difference between real democracy and a thin

veneer of freedom (just enough to keep the tourists coming) could rest on how

much the ordinary people of Myanmar are prepared to risk, but it could also

rest partly on how readily citizens of other nations step up and demand that

their governments monitor events and hold the government of Myanmar

accountable.

For updates click homepage

here