Following the events from a week ago a tenuous calm

has prevailed in Lebanon. However, a closer look at the activities of Lebanon's

radical Sunni Islamist groups and Shiite militant organization Hezbollah reveals that something is afoot. For one

there are indications that various Lebanese Sunni Islamist groups are

collaborating in an effort to mobilize a militia to

fight in Syria. At the same time Hezbollah is planning to do likewise.

Assad planning for after collapse of his regime

On 1 October in our

prediction for this quarter we wrote that: The Syrian regime is weakening but

is unlikely to collapse by or before the end of 2012.The longer the war lasts,

the higher the probability that Syria will experience a "Lebanonization," which could ultimately see the al Assad regime and the Alawites devolve into just

another clan among many fighting from a regional position rather than as a

national entity.

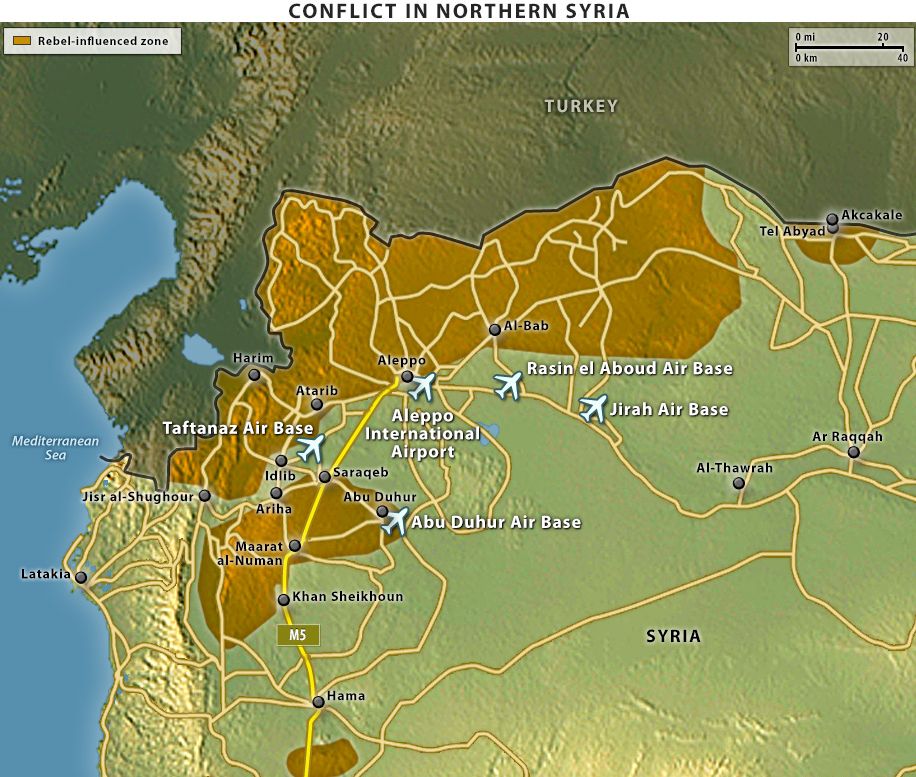

In fact a decision for the deployment of

peacekeepers ("blue helmets") by the end of December in Syria is

currently the most likely outcome. Yet at the same time it appears that rebels'

gains in the north might soon be irreversible.

Thus Syria's beleaguered president, Bashar al Assad, might

be charting a course of events in his country after the possible collapse of

his regime. Post-al Assad Syria will not turn into a democracy; instead, it

will emerge as a country thoroughly fragmented along ethnic, sectarian and

regional lines. Al Assad has definitely succeeded in

pitting not only Kurds against Arabs but also against fellow Kurds who are

allied with the Free Syrian Army.

The FSA should not rejoice over the fact that Kurds are engaged in

fratricide because it has happened before among Kurds in Turkey and Iraq. That

tribal Kurds are divided has not prevented them from eventually presenting

themselves as a serious challenge to the central government. Syrian Kurds are

currently going through the same phase of communal solidarity and political

evolution that their brethren elsewhere in the region went through years ago. A

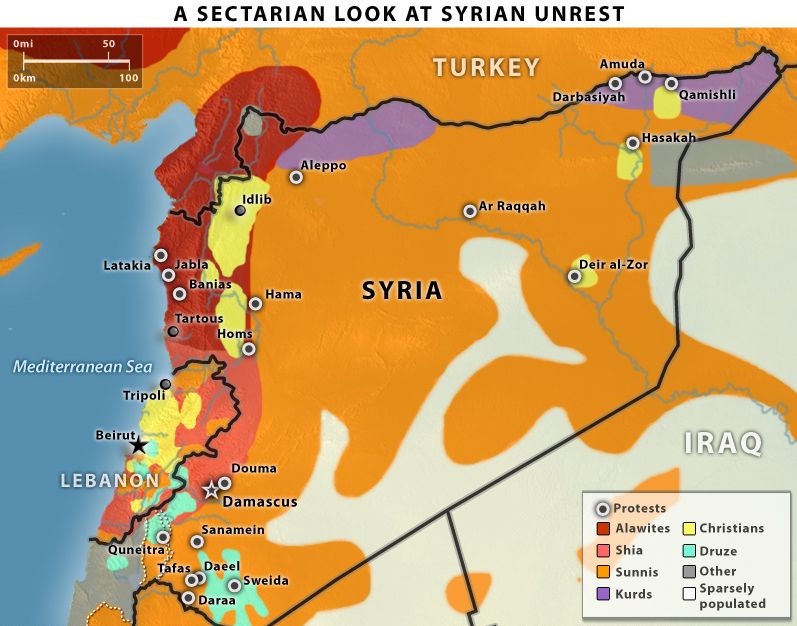

main political fault line in post-al Assad Syria will be between

Arabs and Kurds.

Syria's complex demographics make it a difficult country to rule. It is

believed that three-fourths of the country's roughly 22 million people are

Sunnis, including most of the Kurdish minority in the northeast. Given the

volatility that generally accompanies sectarianism, Syria deliberately avoids

conducting censuses on religious demographics, making it difficult to

determine, for example, exactly how big the country's Alawite minority has

grown.

Alawite power in Syria is only about five decades old. The Alawites are

frequently (and erroneously) categorized as Shia, have many things in common

with Christians and are often shunned by Sunnis and Shia alike.

Between 1920 and 1946, the French mandate provided the first critical

boost to Syria's Alawite community. In 1920, the French, who had spent years

trying to legitimize and support the Alawites against an Ottoman-backed Sunni

majority, had the Nusayris change their name to

Alawites to emphasize the sect's connection to the Prophet's cousin and

son-in-law Ali and to Shiite Islam.

The Sunnis quickly reasserted their political prowess in post-colonial

Syria and worked to sideline Alawites from the government, businesses and

courts. However, the Sunnis also made a fateful error in overlooking the heavy

Alawite presence in the armed forces.

Thus the second major pillar supporting the Alawite rise

came with the birth of the Baath party in Syria in 1947. For economically

disadvantaged religious outcasts like Alawites, the Baathist campaign of

secularism, socialism and Arab nationalism provided the ideal platform and

political vehicle to organize and unify around.

In a remarkably short period, the 40-year reign of the al Assad regime

has since seen the complete consolidation of power by Syrian Alawites who, just

a few decades earlier, were written off by the Sunni majority as powerless,

heretical peasants.

Also today Syria's Sunni Arabs will not be able to benefit

from the comfort of their majority status -- they constitute 60 percent of the

country's total population -- because they are segmented along regional lines

as well as urban vs. rural lines. There is little in common between the

metropolises of Damascus and Aleppo. The latter had always turned to Mosul and

Baghdad, whereas the former had historically identified with Egypt and locally

felt much closer to the cities of Beirut, Tripoli and Jerusalem. There is no

Kurdish issue for the residents of Damascus because Kurds there have been

"Arabized" over the centuries. The vast countryside of Aleppo has

left more than 700,000 rural Kurds bitter, alienated

and unaffected by the city's rise as the country's economic hub. Whereas Turkey

appears positioned to establish itself as the regional hegemon in northern

Syria, the Hashemites in Jordan will certainly try to carve for themselves a

unique place in southwestern Syria, including Damascus, which they see as a prize.

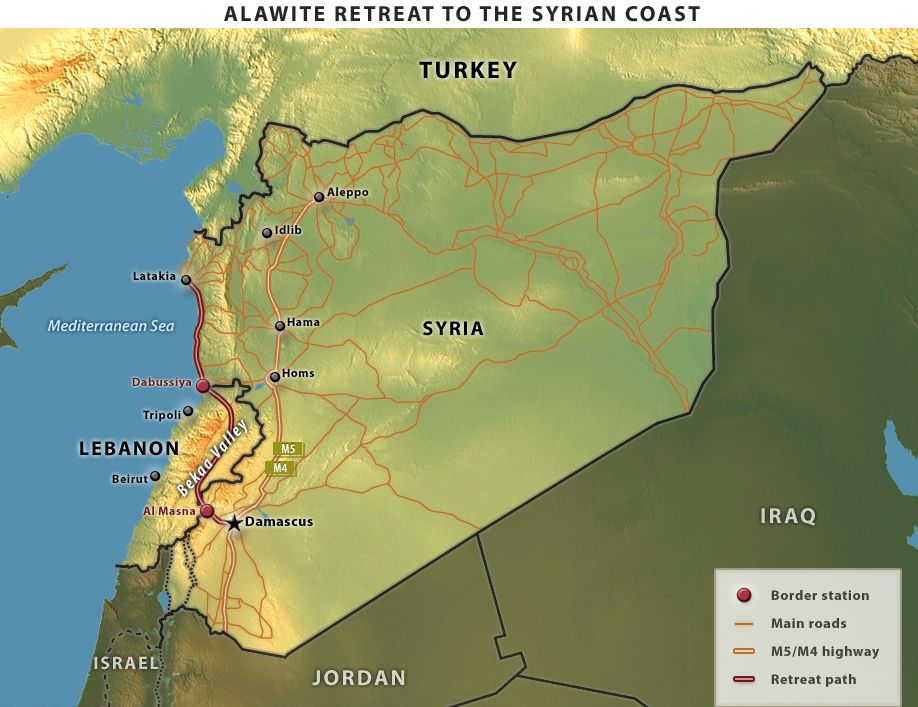

Syria's Alawites on the coast are readying themselves to eventually ally

with Maronites in northern Lebanon and Shia in the northern Bekaa area.

Hezbollah's military activity along the Orontes River Basin points in

that direction.

In the end Syria may maintain its status as a unitary state, but it will

emerge as a highly unstable and fragmented country. The struggle for Syria that

predominated the country's politics during the 1950s will most likely resume on

a much larger scale this time. Should al Assad physically survive his country's

bloody conflict, he will be able to tell his critics, "I told you

so."

If a currently discussed UN deployment of peacekeepers ("blue

helmets") in Syria where to be agreed upon it would come at the expense of

Saudi Arabia, France, Qatar and Turkey - all of whom back the Syrian revolt and

demand regime change in Damascus. This anti-Assad coalition is now split

between those demanding a compromise solution and those trying to sabotage the

process underway between Washington and Moscow. However

nobody knows what Assad or Tehran will do, Assad may veto the project; so too

might Tehran.

Given the precarious position in which the regime finds itself in the

north, it has reportedly already begun contingency planning for the next stage

of the war. In a case where regime forces are overwhelmed in Aleppo and Idlib,

large numbers of troops will continue to be stationed in Damascus while forces

in the north will fall back on Hama and Homs to maintain a secure line of

communication to the Alawite coast. Although the rebels will continue to face

considerable opposition from a still-heavily armed regime force, their

strategic position will have improved.

For updates click homepage

here