U.S.-China tensions faded rapidly later in 2001 after the attacks in Washington and New York, but China continued to play the Olympics up as both a tool to rally nationalism among domestic and overseas Chinese, and as a public relations initiative to demonstrate China’s emergence among the major world powers. This was further reinforced (in Beijing’s eyes) by the rapid rise of China’s economy in the succeeding years, as China climbed the global gross domestic product ranking ladder to 4th place in 2007, passing most of the European nations and closing the gap with Japan.

As the Olympics drew nearer, Beijing grew concerned with a whole host of potential problems, seeing 2007 as the most critical year — a year that it anticipated would bring a confluence of political pressures from Taiwan and the United States amid growing concerns of economic problems at home and abroad. Beijing’s fears of a perfect storm for 2007 ultimately proved overblown. But just as the Chinese leadership was breathing a sigh of relief, 2008 brought about a whole host of problems ranging from domestic security threats to a hammering of China’s image overseas.

On March 5, a Chinese man carrying what he claimed was a bomb hijacked a bus full of Australians in Xian, raising concerns about transportation security in China, and Beijing’s ability to counter threats from common citizens (as opposed to the “separatist” or “extremist” groups Beijing had been focusing on up to that point). Just days later, on March 7, Chinese security forces thwarted an alleged attempt to bring down a Chinese airliner flying from Xinjiang to Beijing. According to Chinese authorities, the incident was perpetrated by Uighur militant separatists linked to al Qaeda and the international jihadist movement.

This was seen as further evidence of what Beijing had been warning about all along, namely, that Uighur terrorists were targeting the Olympic games. Many observers outside China saw this claim as fairly spurious, and more likely to be a convenient excuse to crack down on the ethnic Uighurs and tighten security overall rather than a response to serious and identifiable threat. But even as Beijing was warning about the threat the Uighurs posed to the Olympics, the annual March 10 demonstrations in Tibet marking Tibet’s failed 1959 uprising against Chinese forces suddenly grew violent, triggering several days of riots in Lhasa and other Tibetan cities until Chinese troops intervened.

Beijing saw this as instigation not only by the Dalai Lama, but by his foreign supporters, including the United States. This view as reinforced when it became known that members of CANVAS, a Serbian-based but U.S.-funded group that teaches nonviolent movements and helped train activists in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution and Georgia’s Rose Revolution, among others, had held a session with members of the Central Tibetan Administration — Tibet’s “government in exile” — in India a week before the Lhasa demonstrations. And it didn’t help matters that the Dalai Lama was scheduled to visit the United States in March as well.

China’s reaction to the Tibet uprising was anything but subtle. But while Beijing tried to play up the violence perpetrated by the Tibetans against Han Chinese as an excuse for its heavy-handed response and as a way to reduce support for the Tibetans internationally, Chinese authorities found little sympathy overseas. Worse for Beijing, the Tibetan rising and Chinese response reinvigorated a plethora of organizations who had planned to target China’s hosting of the Olympics but had largely fallen off the radar screen. When the Olympic torch was lit in Athens, Greece, on March 24 to begin its multination tour ahead of the opening ceremonies, protesters were there to greet it — just as they were at stops in London, Paris and San Francisco. The torch run wound up facing significant disruptions as anti-China demonstrators took the opportunity to air their messages.

These demonstrations triggered counterdemonstrations by overseas Chinese, seen first in force in San Francisco. These actions were compounded by grassroots Chinese boycotts of French goods and a war of words between Beijing and Paris. As the Chinese counteractivism receded, the political problems for Beijing continued as various world leaders announced their intentions to meet with the Dalai Lama on his foreign tours and debated (and in some cases decided against) attending the opening ceremonies in Beijing.

China’s political problems continued through April — when Beijing had to recall a shipload of arms destined for Zimbabwe amid international condemnation — and on into May — as Beijing found itself on the defensive politically. All the while, Beijing faced increasing security threats domestically, not only from potential foreign demonstrators planning on attending and disrupting the Olympics, but also from economic and social stresses triggered by a falling stock market and rising food and fuel costs and emerging murmurs of discontent about spending on the Olympics when people could not afford food.

As Beijing struggled with economic pressures, internal debate over the most effective measures to counter the confluence of problems grew more intense. With the combination of internal and external pressures increasing, it was only the tragedy of the May 12 Sichuan earthquake that brought Beijing some reprieve from international stresses. But while this diverted some of the international criticisms, it did nothing to stem the broader problems facing the Chinese economy and Beijing’s policymakers.

With economic concerns and their attendant social consequences foremost in Beijing’s mind, China shifted from trying to continue using the Olympics as a show of strength to the international community to focusing almost solely on ensuring no further embarrassing or disruptive events happen to undermine the Olympics. Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping toned down expectations from the Beijing Olympics during a July visit to Hong Kong and the Middle East, using the phrase “common attitude” in regard to how others and China may view the Olympics. He even suggested the games should be viewed as a sporting event, not a political demonstration. Chinese media has also taken a similar line recently, seeking to reduce expectations and noting that there remains a wide gap between China and other developed nations — arguing that it is thus not necessarily reasonable to expect China to host the best games ever.

With the shift from political show to simply pulling it off without further interruptions, responsibility for Olympic success passed from the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games to the Public Security Bureau (PSB), China’s state security apparatus. Security issues and China’s inherent paranoia were already impacting the potential economic returns from the Olympics. (No country earns money from the Olympics anymore, though local businesses usually do.) But this only accelerated as local businesses were being ordered to shut down during the Olympics, visa restrictions were being stepped up and the general climate in Beijing went from one of welcoming an international sporting event to one of security lockdown.

The combination of the global economic slowdown, the political backlash from the Tibet rising and the ever more stringent security measures — which is preventing even some of the Olympic sponsors from getting visas for their own staff and executives to attend the Olympic games — has led to a further slowing of both tourist interest in the Olympics and economic interest in China. One sign of this is seen in the Beijing Tourism Administration’s estimates of foreign tourists for the Olympics. In 2004, BTA estimated some 800,000 foreign tourists would come to Beijing during the Olympics, a number that shrank to between 450,000-500,000 in March, and was revised down again in July to 400,000-450,000.

The significant increase in security is not only impacting foreign tourists and businesses; it is spurring debate inside China as well. With the PSB focused only on ensuring there is no embarrassing or dangerous event during the Olympics, and operating under a premise that appears to almost determine the best way to avoid incidents is to make sure no one even comes to the games, economic and even political concerns are falling by the wayside. And this is contributing to the internal debate.

There are mixed views in Beijing, but in general they fall into two categories. On the one side are those advocating the tighter security, hoping to cut China’s loses and make sure at all costs that no terrorist attack or large-scale demonstration or protest occurs. They see foreign powers, and particularly the United States, as instigators of problems inside China, and want to demonstrate that China is not too weak to defend itself. They are also looking down the road and see converging economic and social problems as something that needs addressed — and with a strong hand. The Olympics can provide the pretext for stricter security measures that may carry on well past August.

On the other side are those arguing that there need to be continued economic benefits from the Olympics, and that the best allies Beijing has internationally are not foreign governments but foreign businesses. Restricting business activity, locking out foreign executives due to more stringent visa procedures and sealing off Beijing to travel from other parts of China — and thus from the foreign and domestic businessmen based there — are only going to cause the flight of business interests Beijing has long feared.

And now this attack came following a July 25 video release from the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) warning of further attacks during the Olympics.

While the TIP claims were exaggerated, the attack in Kashi appears to demonstrate that either TIP or those inspired by their message are capable of attacks.

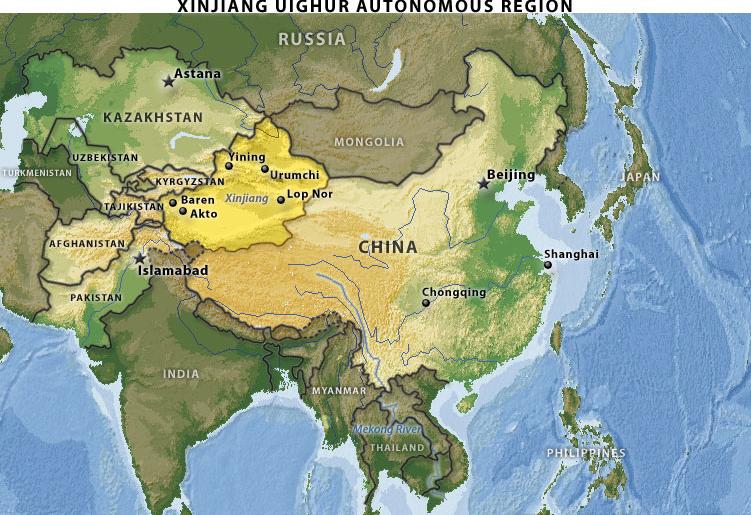

By its own admission, TIP is just one manifestation of a long-standing — though intermittent — Islamist militant Uighur independence movement that also has used the name East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM).

China repeatedly refers to the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) as the main militant Uighur Islamist threat; however, in many Chinese studies, a more general “East Turkistan Movement” is referred to rather than any specific group. When a specific group is mentioned regarding a militant action or government raid, Beijing usually cites ETIM or the related East Turkistan Liberation Organization (ETLO), which is also on China’s most-wanted list. This ambiguity, and the fact that there are numerous variations of the movement’s name, has led many foreign observers to simply credit ETIM with all militant attacks or plots in China. (When the U.S. State Department listed ETIM as a terrorist organization, it credited it with the complete laundry list of attacks, assassinations and plots China said were the work of the entire East Turkistan separatist movement.)

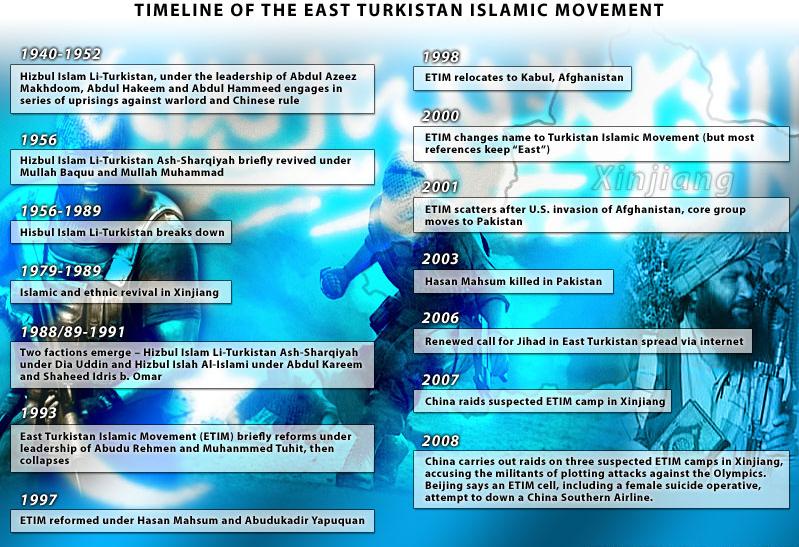

While most reports trace the ETIM back to its rebirth under Hasan Mahsum and Abudukadir Yapuquan in 1997, the organization traces its own lineage back to 1940, when the Hizbul Islam Li-Turkistan (Islamic Party of Turkistan or Turkistan Islamic Movement) was founded by Abdul Azeez Makhdoom (also transliterated as Mahsum), Abdul Hakeem and Abdul Hameed. From the 1940s through 1952, the three led the movement in a series of uprisings, first against local warlords and later against the Chinese Communists. During this time, Abdul Hakeem was imprisoned, Abdul Hameed was driven underground and later killed in 1955 and Abdul Azeez Makhdoom simply dropped out of sight (likely killed).

Around 1956,

after Abdul Hameed’s death, the organization reformed as Hizbul Islam

Li-Turkistan Ash-Sharqiyah (Islamic Party of East Turkistan or East Turkistan

Islamic Movement) under the new leadership of Mullah Baquee and Mullah

Muhammad. The two led an uprising that was quickly defeated, leading to

a decline of the organization and its activity until the late 1970s or

early 1980s. While there were some uprisings in Xinjiang in the 1960s and

1970s during the Cultural Revolution, these were less ethnically or religiously

motivated than linked to the broader sense of instability in China during

that period.

In 1979, as

Deng Xiaoping was launching China’s economic opening and reform, Abdul

Hakeem was released from prison and set up several underground schools

for Islamic study (a slightly more open environment in China contributed

to a decade-long Islamic and ethnic revival in Xinjiang). One of his students

in Kargharlak from 1984 to 1989 was Mahsum, who would later reinvigorate

the ETIM. The 1980s also saw a resurgence of activism among Uighurs in

Xinjiang and elsewhere in China, triggered by calls for religious or ethnic

rights, greater student freedoms and opposition to Chinese nuclear tests

at Lop Nor in Xinjiang.

On Dec. 12, 1985, demonstrations broke out at Xinjiang University, led by a Uighur student organization, and quickly spread to universities and schools in other cities in Xinjiang. The December 12 Movement, as it was later called, was suppressed by Chinese security forces, but it did inspire a second movement in June 1988 triggered in part by leaflets found at the campus of Xinjiang University disparaging ethnic Uighurs. Once again, a Uighur student movement spearheaded the demonstrations, which spread beyond the Xinjiang University campus. A third student-led demonstration broke out in May 1989, when students marched in Urumchi to protest a book on ethnic sexual customs published earlier in Shanghai that allegedly insulted Muslims and Uighurs.

Many of these Xinjiang student protests in the 1980s were more a reflection of the growing student activism in China as a whole (culminating in the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident) than a resurgence of Uighur separatism. But there was also a movement in Xinjiang during the more open 1980s to promote literacy and to refocus on religious and ethnic heritage that saw a resurgence of Islamic schools and mosques. This movement was to take on a stronger role with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the independence of the Central Asian states and the broader Islamic revival in Central Asia.

In 1988 or 1989, the group Hizbul Islam Li-Turkistan Ash-Sharqiyah was revitalized once again under Dia Uddin, who planned a series of attacks in Xinjiang to push for independence from Beijing. The plots were discovered before they could be carried out, however, leading to a clash between government forces and Dia Uddin’s militants in Baren in 1990. The so-called “April 5 Baren Incident” involved some 200 Uighur demonstrators who fought back against government troops, though the core militants were only a dozen or less. After holding the town for nearly three weeks, most of the militants were either captured or killed in the city or in mopping-up operations in the countryside.

Prior to the Baren incident, a breakaway faction of the Hizbul Islam Li-Turkistan Ash-Sharqiyah, called Hizbul Islah Al-Islami (The Islamic Party of Reformation), led by Abdul Kareem and Shaheed Idris bin Omar, carried out several car and bus bombings in Urumchi in 1989 and early 1990. This was not the only small faction to rise up during this time; several smaller Islamist or ethnic militant groups were briefly formed, and Uighur organized-crime groups grew more active as well, making it difficult to determine whether various attacks, robberies and assassinations were the work of separatists, political opponents or criminals.

In the wide security sweep by Beijing following the Baren incident, Mahsum was detained and imprisoned from May 1990 to November 1991. Abdul Kareem was arrested around the same time and imprisoned for 15 years. Many other future leaders of Uighur/East Turkistan movements (political, militant and secular) fled China in the 1980s and 1990s, settling predominately in Central Asia, Turkey and Germany. Inspired by the newly independent Central Asian states, members of this Uighur diaspora held the first Uighur National Congress in Istanbul in December 1992. However, like most overseas and domestic attempts to unite the Uighurs under central coordination, this gathering failed to provide a center of gravity for the nascent Uighur movement.

In Xinjiang, the separatist movement continued to stumble along in the early 1990s, with a series of bus bombings in 1992 and a major demonstration against Chinese nuclear testing at Lop Nor, which degraded into a riot, clashes with security forces and the destruction of military equipment. There were several bombings in Xinjiang in 1993, some attributed by Beijing to the Eastern Turkistan Youths League or the World Uighur Youth Congress. In 1993, Hizbul Islam Li-Turkistan Ash-Sharqiyah founder Abdul Hakeem died, and the movement was briefly reborn under the leadership of Abudu Rehmen and Muhanmmed Tuhit, both from Hotan. (The Islamist factions of Uighur activists arose mostly in the southwestern part of the province, with the secular political movements coming primarily from the center and north.)

In July 1993, Mahsum was imprisoned again and held until February 1995, when he was transferred to a labor camp in which he was confined until April 1996. During this time in prison, Mahsum was one of many Uighurs who shifted from a political Islamic philosophy to a more militant one. The various students, militants, criminals and bystanders picked up in China’s broader sweeps following the 1990 Baren incident began to reshape the militant ideology in prison, which became perfect militant training grounds.

By the mid-1990s, several smaller militant and criminal groups were active in Xinjiang, with names, memberships and ideologies frequently shifting. In 1995, China began to crack down on Islamic teaching in Xinjiang. In July of that year, authorities arrested two imams in Hotan, which led to riots and clashes with security forces. China further intensified its efforts to stem the rise of Islamist and separatist militancy in Xinjiang in 1996 by forming the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (at the time referred to as the Shanghai Five), establishing new security arrangements with Russia and Central Asian states and encouraging Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to clamp down on the political and militant activities of the Uighur diaspora in Central Asia.

This was followed by a series of so-called “strike hard” campaigns in Xinjiang by Chinese security forces. But rather than quell separatism and militancy, this move caused a flare-up in Xinjiang as Beijing tightened its grip. In 1996, Mehmet Emin Hazret founded the East Turkistan Liberation Organization (ETLO), and future members of ETIM started their own militant groups in Xinjiang, carrying out a series of armed attacks against political, religious and business leaders. That same year, a larger flood of Uighurs left China, seeking shelter in Central Asia and Afghanistan. During one of the “strike hard” campaigns in August 1996, Mahsum was again briefly detained. Upon his release, he traveled from Urumchi to Beijing to Malaysia and on to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

From January

to March 1997, Mahsum stayed in Jeddah and tried to convince the local

Uighur community, including wealthy businessmen, to fund or join a Uighur/East

Turkistan Islamist militancy and challenge Beijing’s rule over Xinjiang.

He received very little support, with many of the economically or socially

influential in Jeddah calling militancy a lost cause and urging Mahsum

to change his mind and simply settle overseas. This is a repeating theme

in the timeline of Islamist militancy in Xinjiang — the near lack of

support by the broader community, both domestic and abroad, and particularly

the economic elite.

In March and

April 1997, Mahsum took his cause to Pakistan, then on to Turkey in April

and May. Both missions met with similar results as his Jeddah initiative,

despite reports of another Uighur uprising in Xinjiang in February 1997,

resulting in several days of clashes between Chinese security forces and

Uighur protestors in Yining. Following the Hajj in Saudi Arabia in May,

Mahsum and a small group of followers headed to Central Asia, likely Afghanistan,

where they began to interact with the broader Islamist/jihadist movement.

Around September 1997, Mahsum and Abudukadir Yapuquan reformed ETIM, the direct descendent of his former teacher Abdul Hakeem’s Hizbul Islam Li-Turkistan Ash-Sharqiyah. In March 1998, with about a dozen members present, ETIM formalized its ideology and mission, rejecting much of Dia Uddin’s ideas from the late 1980s and seeking broader regional ties. This new manifestation of ETIM sought closer cooperation with other Turkic peoples and non-Uighurs abroad and no longer focused on starting an uprising or holding territory in Xinjiang. In September 1998, ETIM moved its headquarters to Kabul, Afghanistan, taking shelter in the Taliban-controlled territory.

In 1997, while Mahsum was abroad seeking foreign support for the Uighur Islamist militancy, the movement was taking a different direction in Xinjiang. A series of bombings that year against buildings and transportation infrastructure in Xinjiang was credited to various small militant groups — some with evocative names like the “Wolves of Lop Nor.” In March 1997, a bus bombing in Beijing was credited by some to Uighur militants and was even claimed by at least one overseas Uighur movement. However, some Chinese reports played down the link, suggesting the bus attack was a purely criminal act. If the perpetrators were indeed Uighur militants, the bus bombing would be the farthest successful Uighur attack in China away from Xinjiang. ETLO also was blamed for a series of attacks and assassinations in Central Asia in 1998.

As the Uighur militancy was picking up steam, social and political movements also began expanding their activities and boldness. Several social movements emerged focusing on AIDS awareness and prevention, stemming illegal drug use, promoting literacy and empowering women. Among these was the Thousand Mothers Movement, started by Rebiya Kadeer, who, as one of Xinjiang’s wealthiest business leaders and a member of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC), had used the NPC session in Beijing in March 1997 to criticize China’s policies in Xinjiang. Kadeer was later arrested in 1999, and she eventually was released to the United States as a show of goodwill in March 2005, days before U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice was to arrive in China. Kadeer has since been characterized as the Uighur “Dalai Lama,” or the mother of the Uighur movement, and now lives in the United States.

Meanwhile, following the relocation of its headquarters to Kabul in late 1998, ETIM largely gave up on the wider overseas Uighur community (although it reportedly established an alliance with ETLO in March 1998) and began to take advantage of the regional jihadist movement, particularly in Afghanistan, for support and training. ETIM also began reaching back into Xinjiang, establishing contacts with criminal and militant groups such as the hybrid Hotan Kulex, which manufactured explosives and carried out a series of robberies and assassinations in Xinjiang in 1999.

On March 17, 1999, militants suspected of links to ETIM attacked a convoy of People’s Liberation Army trucks in the suburb of Changji City, some 50 miles from Urumchi. In less than a week, Chinese security forces issued a bulletin saying they had wiped out the militant cell responsible. In September 1999, police broke up a “political rebellion” in Hotan. Meanwhile, Mahsum and other ETIM leaders reportedly met in Afghanistan with Osama bin Laden and other leaders of al Qaeda, the Taliban and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) to coordinate actions. In response to this wider mandate, ETIM removed the “East” from its name, thus becoming the Turkistan Islamic Movement (not to be confused with the Islamic Movement of Turkistan, a name taken on by the IMU in 2003 as it sought to broaden its mandate beyond Uzbekistan). Despite the name change, most analysts and even Islamists continue to refer to the group by its more common English abbreviation, ETIM, just as the Islamic Movement of Turkistan continued to go by IMU after it changed its name.

For much of 2000 and 2001, ETIM sought to recruit Uighurs heading to Central Asia, Afghanistan or the Middle East for Islamic training. In addition, Uighurs gained experience at training facilities in Afghanistan and on occasional operations with the Taliban. ETIM had minimal connections back in Xinjiang during this time, though Uighurs also joined individually with the IMU and other movements in Central Asia. In February 2001, bin Laden and Taliban leaders reportedly met to discuss further assistance to the various East Turkistan and Central Asian Islamist militant movements, including ETIM. But al Qaeda’s attention soon shifted to the upcoming attacks on the United States, and the Taliban prepared to strengthen its operations against the forces of the Northern Alliance in anticipation of the al Qaeda strike and repercussions from Washington.

With the U.S. attack on Afghanistan in October 2001, both ETIM and IMU were routed, along with Taliban and al Qaeda forces. The remnants of ETIM, including Mahsum, relocated to Central Asia and Pakistan, though there are suggestions that Yapuquan went to Saudi Arabia. In January 2002, Mahsum conducted an interview with Radio Free Asia, claiming that ETIM had no links to al Qaeda or the Taliban but admitting that some individual members may have fought alongside other militants in Afghanistan. With little international attention, sympathy or support for the Uighur movement anywhere (even among the Islamic community), Mahsum was seeking to avoid having the Uighur movement lumped in with the broader jihadist movement and coming under U.S. guns. It did not work.

In September

2002, the U.S. State Department listed ETIM as a terrorist organization,

following an August warning that ETIM could be planning attacks against

U.S. interests in Kyrgyzstan. While there were disagreements in the U.S.

intelligence community at the time (with several arguing that ETIM was

a fractured and largely defunct organization after it fled Afghanistan

in 2001), the listing not only undermined any potential sympathy ETIM might

have gained in its fight against Beijing, it also weakened the wider political

Uighur movements, which had to fight an assumed link with international

Islamist terrorism.

In 2003, ETIM

experienced what seemed to be its last gasps, with Beijing claiming to

have cracked a small ETIM cell in Hebei province (which borders Beijing)

and with Kazakhstan claiming to have dismantled another suspected ETIM

cell. The biggest blow to the organization came in October, when Mahsum

was one of several killed in a joint Pakistani-U.S. operation against multinational

militant targets in Angoor Adda, South Waziristan. Mahsum’s death left

an already-fractured ETIM largely leaderless. With the exception of ETIM’s

being listed as one of China’s most-wanted terrorist organizations in

December 2003, there was little mention of ETIM activity until 2007, when

Beijing began ramping up security ahead of the Olympics.

In the latter half of 2006, a video was circulated on the Internet urging a new jihad in Xinjiang. Much of the media and literature that began readdressing the Uighur cause emanated from Pakistan, where some ETIM remnants and other militant Uighur Islamists had integrated with multinational jihadist forces. By late 2006, there were reports that ETIM remnants had begun reforming in the far western reaches of Xinjiang, preparing to take the fight back to Chinese territory.

In early January 2007, Beijing raided a camp of suspected ETIM militants in Akto County, which sits along the Chinese border with Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan, killing 18 and capturing another 17, along with firearms and homemade grenades. By that time, Beijing started to grow worried that Uighur militants training in Pakistan were beginning to filter back into Xinjiang to recruit and plan attacks. In May, Beijing urged Pakistan to detain some 20 Uighurs linked to ETIM who Chinese intelligence thought were hiding in the Pakistani trial areas.

In January 2008, Chinese security forces carried out another raid on a suspected ETIM camp, this time in the Tianshan district of Urumchi, killing two and detaining 15, as well as uncovering a cache of knives and axes, “terrorist” literature and plans to carry out attacks during the Olympics. (Later reports suggested the plans were to carry out attacks to mark the anniversary of the February 1997 uprising in Yining.)

The January raids were discussed on the sidelines of the March NPC session in Beijing, when officials also reported an attempt by a Uighur militant to down a Chinese passenger jet on March 7. In that case, Turdi Guzalinur, a 19-year-old Uighur, allegedly smuggled two containers of gasoline aboard China Southern Airlines flight CZ6901 from Urumchi to Beijing and attempted to set a fire in the restroom in order to crash the aircraft. Chinese state security officials said she was trained by her husband, a Uighur from Central Asia, and was traveling on a Pakistani passport. Some reports suggested that as many as four individuals were involved in the plot, either directly or indirectly, and that the mastermind had fled China for Central Asia.

The attempted jetliner bombing triggered a series of changes in Chinese airline security to tighten up search and carry-on regulations already on the books but only sporadically enforced. The incident was quickly overshadowed just over a week later, however, when protests in Tibet broke into open riots and international attention shifted away from the Uighurs to the Tibetans. A March 23 anti-government protest in Hotan went nearly unnoticed, as did a series of counterterrorism raids by Chinese security forces between March 26 and April 6 that netted 45 alleged militants as well as explosives and jihadist literature. According to Chinese security officials, the raids also uncovered plots to attack Beijing and Shanghai during the Olympics.

Following the raids, Beijing warned India of potential ETIM members infiltrating New Delhi to carry out terrorist acts coinciding with the Olympic torch run, and Beijing repeated its accusation that ETIM was still active and operating from Pakistani territory. At the same time, security forces in Beijing and Shanghai were also alerted to look for Muslims in Beijing and Shanghai who could be infiltrating schools and office buildings to survey them for possible attacks. In addition, there were increased warnings to be on alert for foreign Muslim women, who could be conducting surveillance of potential targets in Chinese cities or even preparing for attacks themselves. The focus on foreigners, rather than just Uighurs, was a further recognition of the internationalization of the jihadist movement against China.

There are indications that a small number of Uighur militants remain among groups of foreign militants in Pakistan, either in the tribal areas or in Kashmir, and occasionally travel back into Afghanistan and Xinjiang. If the March 7 airline incident is any indication, the foreign influence and connections in the Uighur movements in Xinjiang are continuing to expand, and the overseas training and study are facilitating the sharing of tactics, experiences and preferred target sets.

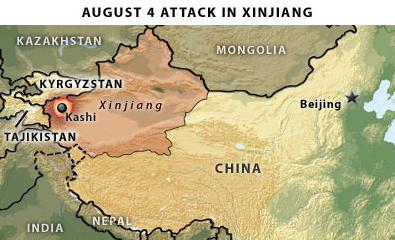

Chinese officials have released sufficient information on the attack against the border police detachment in Kashi Kashgar( city in Xinjiang province). According to the most recent report today, the two attackers, Uighur men aged 28 and 33, drove their dump truck into a group of some 70 border police jogging past the Yiquan hotel, a little more than 300 feet from the border police compound. In addition to driving the vehicle into the group, the attackers threw homemade explosives at the police from the vehicle. The attack killed 16 police officers and injured another 16.

The driver then lost control and crashed the truck into a utility pole. The two men then apparently tried to escape, fighting with the police using knives, before being captured. The driver of the truck had blown off part of his arm after one of the explosive devises detonated in his hand. It is unclear whether this happened after or before the crash — if before, it might have been what caused the driver to lose control. Police found an additional 10 explosive devices in the vehicle, as well as four knives and a homemade gun.

It is unclear whether the attack was initially designed to target the police in the street, as opposed to the police station itself. However, it is highly likely that the officers follow a regular morning routine, so the attackers would probably have known there would be a large gathering of closely grouped and unarmed police in the area each morning. The most effective element of the attack was not the explosives — which seem to have injured the attackers more than their targets — but rather the simple use of a large vehicle to ram into the police detachment.

The attack shows planning, but not a significant level of sophistication — though it does demonstrate that sophistication is not always necessary for success. In addition, the use of homemade devices, including the homemade gun, suggests the attackers either do not have access to commercial or military weapons (and thus minimal links to supply lines from outside Xinjiang) or they chose not to use them. This follows some earlier examples of Islamist Uighur militant groups, who trained and indoctrinated potential militants outside Xinjiang and then sent them back into China, sometimes with weapons and sometimes without, allowing them to choose the time and method of their attack on the establishment.

The implication is that this attack comes at the behest of, or at least inspired by, the Turkistan Islamic Party or some related group, following up the July 25 video warning of further attacks. The small scale of the attack (despite the relatively high casualty count for an attack in China) may reflect a small and independent self-made cell operation, part of a movement with minimal connections between cells or back to a central leadership node. The cell is more likely to be inspired by ideology than specifically directed by an external leadership, with the apex leaders issuing videos and other media to inspire and draw attention to (and take credit for) activities, but remaining distant from the actual operators.

This would suggest an evolution in Xinjiang militancy. The militants evidently are learning from the broader regional jihadist movement of the benefits of such a loosely affiliated structure — one that requires only a small core of planners, ideologues and operatives, isolated from the broader “inspired” movement that carries out attacks in a near-autonomous fashion. Thus if security forces crack one cell, it is difficult to trace it back to other cells or to the central leadership — making it harder for Chinese security forces to control or contain.

If there is further evolution along these lines among the Uighur militants, security forces will be faced with an increasing number of small-scale actions — increasing the tactical threat even if the strategic threat to Beijing remains small. Perhaps the biggest threat is damage to China’s image, and possible local repercussions of security operations China carries out in places other than Xinjiang.

Conclusion: By 1998, Kabul-based ETIM began recruiting and training Uighur militants while expanding ties with the emerging jihadist movement in the region, dropping the “East” from its name to reflect these deepening ties. Until the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, ETIM focused on recruiting and training Uighur militants at a camp run by Mahsum and Abdul Haq, who is cited by TIP now as its spiritual leader.

With the U.S. attack on Afghanistan in October 2001, ETIM was routed and its remnants fled to Central Asia and Pakistan. In January 2002, Mahsum tried to distance ETIM from al Qaeda in an attempt to avoid having the Uighur movement come under U.S. guns.(1) It did not work. In September 2002, the United States declared ETIM a terrorist organization at the behest of China. A year later, ETIM experienced what seemed to be its last gasps, with a joint U.S.-Pakistani operation in South Waziristan in October 2003 killing Hasan Mahsum.(2)

On July 25, 2008, TIP released a video claiming responsibility for a series of attacks in China, including bus bombings in Kunming, a bus fire in Shanghai and a tractor bombing in Wenzhou. While these claims were almost certainly exaggerated, the Aug. 4 attack in Xinjiang suddenly refocused attention on the TIP and its earlier threats.

Further complicating things for Beijing are the transnational linkages ETIM forged and TIP has maintained. The Turkistan movement includes not only China’s Uighurs but also crosses into Uzbekistan, parts of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan and spreads back through Central Asia all the way to Turkey. These linkages may have been the focus of quiet security warnings beginning around March that Afghan, Middle Eastern and Central Asian migrants and tourists were spotted carrying out surveillance of schools, hotels and government buildings in Beijing and Shanghai — possibly part of an attack cycle.

The alleged activities seem to fit a pattern within the international jihadist movement of paying more attention to China. Islamists have considered China something less imperialistic, and thus less threatening, than the United States and European powers, but this began changing with the launch of the SCO, and the trend has been accelerating with China’s expanded involvement in Africa and Central Asia and its continued support for Pakistan’s government. China’s rising profile among Islamists has coincided with the rebirth of the Uighur Islamist militant movement just as Beijing embarks on one of its most significant security events: the Summer Olympics.

Whatever name it may go by today — be it Hizbul Islam Li-Turkistan, the East Turkistan Islamic Movement or the Turkistan Islamic Party — the Uighur Islamist militant movement remains a security threat to Beijing. And in its current incarnation, drawing on internationalist resources and experiences and sporting a more diffuse structure, the Uighur militancy may well be getting a second wind.

1) Initially Washington sent the Uighurs to Albania and declared them "noncombatants" implying that the Uighur threat was manufactured by the Chinese to legitimize a crackdown on separatists in Xinjiang.

2) Chinese state media reported Dec. 23, 2003, that Hasan Mahsum, was killed in Pakistan during an anti-terrorism raid. Beijing claimed he died during a joint U.S.-Pakistani raid on a suspected al Qaeda hideout in south Waziristan province in early December. However, Pakistani military officials said Dec. 23 that troops killed Mahsun on Oct. 2, and they, denied any U.S. involvement in the operation. Beijing also wants the repatriation of more than a dozen Chinese Uighurs who were captured during U.S. operations in Afghanistan and currently are being held at the U.S. detention facility at Guantanamo Bay.

Likely to become a new arena of international interest in the 21st century, not least because of its cocktail of abundant oil and gas, Islamic jihadist groups, dictatorial regimes, and rivalry between Russia, China, Pakistan, the US and Iran. Central Asia P.2.

Hydrocarbons and the Great Powers. Central Asia P.3.