By Eric

Vandenbroeck 4 August 2018

Shantung the Versailles Treaty and the Manchurian

episode

On a stopover in

Honolulu where I will be attending a meeting, I will now complete the synopsis

of some of the things I covered during my seminars in China the previous two

weeks. On 11 July 2017 I already reported the

strivings of Woodrow Wilson during the Versailles deliberations in reference to

Eastern Europe and in particular also Poland. whereby one of the subjects I

was asked to highlight in China was not only the the

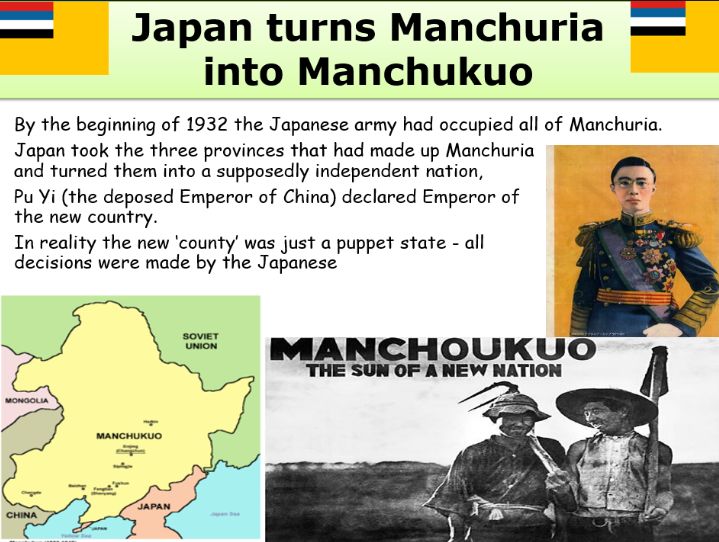

Japanese invasion of Manchuria began on 18 September 1931, when the Kwantung

Army of the Empire of Japan invaded Manchuria immediately following the Mukden

Incident. The Japanese established a puppet state called Manchukuo, and

their occupation lasted until the end of World War II.

Much more important

to the Chinese, even today, is the so called Shantung

incident which ignited to start Chinese nationalism. In fact the Versailles

treaty Articles 128 to 158 specified that treaties made by Germany with a

number of states were to be invalidated. The most important of these concerned

the Chinese Shantung peninsula (Articles 156– 158) where, since 1898, Germany

had held a 99-year lease for 100 square miles at Kiachow

Bay in the south. Here, at Tsingtao, they constructed a harbor where the German

Cruiser Squadron was stationed. Tsingtao was overrun by the Japanese in the

early months of the war, and they expanded their base far beyond the territory

leased to Germany. The Allies, keen to secure continued Japanese assistance in

East Asia and the Pacific, had assured Japan in 1917 that it could take over

from Germany in Shantung after the war, but U.S. delegates at the peace

conference objected to the acquisition. Under pressure to finalize the treaty

in the last days of April, Wilson agreed to a compromise: Japan could take over

Germany’s economic rights in Shantung - the port, the railways, and the mines -

but had to pull out its occupation forces. When the Chinese delegates were

handed these terms, they left the conference. Japan withdrew from Shantung in

1922, but invaded the Chinese mainland, including Shantung, fifteen years

later. It was the beginning of a war and an occupation that was to take the

life of twenty million Chinese.

What is less known is

the behavior of Woodrow Wilson when end April 1919 Wilson (USA), Clemenceau

(France), and Lloyd George (Britain) settled the last major issue on their

agenda, which was indeed the quarrel between the Republic of China and the

Japanese Empire.1

But what happened

here is that the Japanese had secretly promised military and naval assistance

to the British and the French. The Chinese however had also assisted, and the

latter were now insulted. This whereby the Chinese

claims echoed with Wilson and his 14 points.

The arguments of the

French and in particularly Lloyd George on the other hand was: It is impossible

for us to say to the Japanese: "We were happy to find you in time of war;

but now, good buy!" This whereby the Japanese compounded Wilson's anxieties

by threatening to withdraw from the Peace Conference unless their Chinese claim

was honored. Thus in a double bind, Wilson feared that if the Japanese followed

the Italians out the door and declined to sign the treaty, Wilson

explained, Germany might also decline. And that thus the only hope for world

peace was "to keep the world together get the League of Nations with Japan

in it, and then try to secure justice for the Chinese." So Wilson joined

Clemenceau and Lloyd George in awarding the German rights in Shantung to Japan.

And in the agreement not written into the Versailles treaty Articles, Japan

promised to return Shantung Peninsula to Chinese sovereignty "at the earliest

possible time."

China's faith turned

to anger and disillusion when, in early May 1919, news reached China that the

Big Three had decided to give economic control of the Shandong Peninsula to

Japan. Thousands of protesters marched through the streets of Beijing on May 4,

protesting Japanese businesses, expressing their anger at the Western leaders

in Paris, and burning down the house of a prominent Chinese politician with

ties to Japan. Calls for a full boycott of Western and Japanese goods soon

followed, as did a wave of strikes in Shanghai, Wuhan, and other Chinese

cities.

The view from Japan

Given the above, the

First World War had starkly revealed both China’s weakness and Japan’s

strength. For their part, Japanese leaders knew that the European influence in

Asia would likely decline after the war, and they very much wanted to be the

power that would fill in the resulting vacuum. Their delegation to Paris was

led by Prince Saionji Kinmochi, a seventy-year-old

elder statesman and former prime minister who had studied at the Sorbonne and

had been a classmate of Georges Clemenceau there. Japanese leaders mistrusted

the principles of Woodrow Wilson, seeing right through his noble-sounding

ideals to the racist core that underlay them. As one Japanese newspaper wrote,

Wilson was an angel in rhetoric but a devil indeed. The Japanese knew that

Wilson held Asians to a lower standard of development than he did Europeans.

They also blamed Wilson’s promises of national self-determination for the rise

in anti-Japanese sentiment in both China and Korea. Hoping to catch Wilson in a

trap and expose his hypocrisy, the Japanese delegates came to Paris seeking to

force the insertion of a racial equality clause into the final treaty. Either

the Allies would agree, and thereby undercut their own rationale for

imperialism, or they would refuse and give the Japanese a tremendous public

relations victory across Asia, especially inside the European and American

colonial empires.

But not having China

present among the signatories was another of the bad tastes that the signing

ceremony left behind. British diplomat Sir James Headlam-Morley and American

general Tasker H. Bliss were among the senior officials who sympathized with the

Chinese and thought they had been correct to refuse to put their names on a

treaty so humiliating to their country. The Shandong decision was deeply

unpopular not only among the Chinese, but also among diplomats in Paris who

recognized just how badly it undermined the very principles upon which they

were trying to rebuild the world. Headlam-Morley worried about the

ramifications of China’s noninvolvement in that new world order. Chinese anger

at the West, as well as the West’s acquiescence in Japan’s power grab, would

inevitably lead to an increase in Japanese strength, a development that worried

both the Europeans and the Americans. It also, Headlam-Morley feared, set up

the dangerous possibility of the creation of a bloc of anti–League of Nations

states led by an alliance between Germany, the Soviet Union, and China. Neither

option augured well for the West or for stability in East Asia. The Americans,

too, were worried about the growth of Japanese power, but Wilson scarcely had

time to think about Asia. First he had to find a way to get the US Senate to

approve the Treaty of Versailles and its most controversial provision, the

Covenant of the League of Nations. The battle to do so proved to be one of the

most arduous, partisan, and acrimonious debates in the history of American American politics. In the end it may well have led Wilson

to suffer the strokes that incapacitated him, destroyed the remainder of his

presidency, and muddled his legacy.

As symbols of how

much remained to accomplish, the Italians were showing signs of anger over

Allied refusal to recognize their claims to Fiume, and in China, a series of

protests, some of them violent, had broken out over the news that Japan would

take effective control of the Shandong Peninsula. In March the German minister

of defense, Gustav Noske, had ordered forty thousand members of the Freikorps

paramilitary units to use machine guns, flamethrowers, mortars, and even

airplanes against left-leaning Germans. More than 1,200 of them lay dead.

Sooner or later the negotiations had to end, and the treaty with Germany had to

be signed if any semblance of stability were to return.

The Treaty of Versailles

As I pointed out on

20 Jan. 2017, the League of Nations ratified the Treaty

of Versailles of which I detailed what excactly it

entailed, officially ending World War I with Germany. Much has been written

about the treaty which concluded the First World War, its competing and

sometimes conflicting goals. A second article published shortly thereafter

overed Weimar politics and the Versailles Peace Treaty.

In the elections held

in September 1930, when the number of Nazi representatives rose to 107, the new Nazi members behaved like hooligans at the

first sitting of the new Reichstag. Alan Bullock pointed out that “in speaking

of the Nazi movement as a ‘party’ there is awas no

more a party in the normal democratic sense of the word than the Communist

Party is today. It was an organized conspiracy against the State”. Hitler

himself always insisted that his organization was a movement rather than a

party. 2

Several other factors

combined to weaken the Versailles System as it had been revised by the Treaty of Locarno. The Locarno

Treaties were seven agreements negotiated at Locarno, Switzerland, on 5–16

October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First

World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central and

Eastern Europe sought to secure the post-war territorial settlement, and return

normalizing relations with defeated Germany (the Weimar Republic). It also

stated that Germany would never go to war with the other countries. Locarno

divided borders in Europe into two categories: western, which were guaranteed

by Locarno treaties, and eastern borders of Germany with Poland, which were

open for revision.

The Reparations Conference at Lausanne

This was then

followed by the long delayed Reparations Conference that opened at Lausanne on

17 June 1932, a fortnight after Germany's Brüning Government’s

fall. Brüning was replaced as Chancellor by Franz von Papen, a former

soldier who had joined the Centre Party and now displaced his own Party’s

leader to become Chancellor.

Representatives from

Great Britain, Germany, and France met at Lausanne that resulted in an

agreement to suspend World War I reparations payments imposed on the defeated

countries by the Treaty of Versailles. Thus by this time the British policy was

firmly set towards the cancellation of reparations. At an Anglo-French

conference held at the British Embassy in Paris MacDonald, now Prime Minister

of the National Government, declared that British policy “was that the Great

Powers must agree to wipe the slate clean” (BDFP II, 3: 173) but the French

Prime Minister, Herriot cautioned that if a final settlement was reached at

Lausanne, “the French Government would have an impossible task. It was

necessary to proceed by stages” (ibid.: 175). He went on, “He himself was not

entirely convinced of Germany’s good faith.

The injustices heaped

upon a defeated Germany, allegedly undefeated in the

field and stabbed in the back at home, in effect serve to reinforce an idea

that things would be normal if only the external burdens, imposed by the

allies, could be lifted. One could also argue that the constant, indeed ritual,

complaints about Versailles in effect served to disguise the extent to which

the War had impoverished Germany … These illusions were dangerous … [because] …

as long as the truth about the War, its causes and consequences remained

excluded from mainstream public political discussion, it was impossible to face

harsh economic and political realities … Responsible politics remained a

hostage to myths about the First World War, and Weimar democracy eventually had

to pay the price.3

After the first

plenary sessions at Lausanne there ensued a long series of meetings, some

between the British and the French or the British and the Germans only, others

being more multilateral, which failed to reach agreement until the Conference

was close to having to be adjourned because its leading members were required

by urgent business in their own countries. Much of the disagreement concerned a

proposal that in return for reparations being cancelled, Germany should make a

contribution to the restoration of Europe and would issue bonds to do this but

there was much disagreement on the terms on which these bonds should be issued.

However, by the time the fourth plenary session convened on 8 July, an

agreement had been reached, although agreement was so late that the documents

were not ready for signing and the session had to be adjourned while they were

typed.

On 14 September the

German Foreign Minister, von Neurath advised Henderson that “in view of the

stage reached by the discussions at the Conference the question of equality of

rights for the disarmed states could no longer remain without a solution. On that

occasion, he accordingly declared that the German Government (which had refused

to take part in the conference) could not take part in the further labors of

the Conference before the question of Germany’s equality of rights had been

satisfactorily cleared up”.

The disarmament

question, therefore, remained unresolved and Germany’s intention to rearm was

becoming clearer; for some time her clandestine

attempts to rearm with Soviet Russian help had been known to the Western

allies. In April 1922 Germany and the Soviet Union signed a treaty of trade and

friendship at Rapallo, Italy. The published version of the treaty established

friendly relations between the two nations that included trade and investment.

But the treaty also had a secret annex, signed two months later, that

established close military cooperation between the two powers.

Much has

been written about the appeasement diplomacy that led up to the Second World

War and it is not the primary focus of this article. However, one of the

mainsprings of the Allies’, especially the British, tolerance of Hitler’s early

expansionary moves was the by now well-established view among Western

politicians and newspapermen alike that the terms of the Treaty of Versailles

were unjust and provided a just cause for German complaints and activities.

Lord Lothian, the former Philip Kerr remarked of the reoccupation of the

Rhineland in 1936 that the Germans “were only walking into their own back

garden”. The appeasement policy, which was very much the creation of the

English right wing in Parliament and outside it, was enthusiastically supported

by Geoffrey Dawson, the Editor of The Times and many others, including the

British Ambassador in Berlin, Sir Neville Henderson. Among British Ministers

and their circle of acquaintances, particularly

the group known as the Cliveden Set, support for appeasement and rejection

of the Versailles Treaty was general.

In his policy

statement Mein Kampf Hitler had stated that his major international ambition

was “Lebensraum in the East”, not a desire to attack the Western Powers, which

gave the French and British Governments the hope that diverting Hitler’s

ambitions eastward could be achieved.

Meanwhile Churchill’s

warnings were ignored; Anthony Eden was replaced as Foreign Secretary by a core

member of the Cliveden set, Lord Halifax. Eden became a bitter opponent of the

appeasement policy. Vansittart and the pro-French Foreign Office were marginalised, while Chamberlain increasingly relied instead

on Sir Horace Wilson for advice and reassurance. Like all industrial relations

experts, Wilson would have been expert in negotiations and securing

compromises, rather than facing down enemies. Welcome advice was always

forthcoming from Sir Neville Henderson. The appeasers met up socially

frequently, often at Cliveden but also at All Souls College, Oxford, as A. L.

Rowse recorded:

They would not listen

to warnings because they did not wish to hear. And they did not think things

out because there was a fatal confusion in their minds between the interests of

their social order and the interests of the country. They did not say much about

it because they would have given the game away and anyway it was a thought they

did not wish to be too explicit about even to themselves but they were anti-Red

and that hamstrung them in dealing with the greater immediate danger to their

country, Hitler's Germany.4

In March 1938 Hitler

marched into Vienna and announced the Anschluss of Austria- her incorporation

into the Reich. Next, he demanded the return of the Sudeten Germans to the

Reich, a demand that was granted at the Munich Conference which denuded

Czechoslovakia of her defences against a German

invasion and was followed early the next year by an invasion and occupation of

the entire country. At the time of the Munich conference Chamberlain denied the

need to go to the aid of Czechoslovakia, “A faraway country of which we know

nothing”. On his return from Munich the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain,

notoriously waved the piece of paper that he claimed promised “peace for our

time”, only soon to be proved cruelly wrong. Only then did the Western powers

recognize that Hitler was bent on the aggressive expansion of the Third Reich.

Hitler’s next demand was for the restoration to Germany of Danzig and the

Polish Corridor. This was a step too far and his invasion of Poland on 1

September 1939 provoked the outbreak of the Second World War. All the dreams of

a European peace were lost for the five and a half year duration of what was to

be a terrible second war.

As for the Versailles

Treaty at the Paris Peace Conference (which I earlier covered

in context of the making of the Middle East) the “Big Three” were able to

agree a series of pragmatic compromises that did not always command the support

of their colleagues or publics bemuse they had interests which brought them

together: Clemenceau’s desire to maintain the alliances with Britain and

America, Lloyd George’s search for the means to ensure a lasting European peace

and Wilson’s desire to punish Germany for her wartime and pre-war crimes. The

personal chemistry that developed among them made the agreement of a peace

treaty possible. Then in the early 1920s, the animosity that existed between

Lloyd George and Poincaré prevented any chance of

agreement between them on how to

secure reparations payments.

However studies have

shown that a relatively moderate increase in taxation, coupled with an equally

moderate reduction in consumption, would have enabled the Weimar Republic to

meet the reparation debt.5 In fact, Shuker has shown that the net capital inflow

ran towards Germany in the period 1919 to 1933 at a minimum of at least 2

percent.6

The reparation terms

obliged Germany to pay 50 billion gold marks. Keynes - expecting that the C

Bonds would eventually be canceled - advised the German government to accept.

(Sally Marks, "Reparations Reconsidered: A Reminder," Central European

History 2, p.361.)

The historian of

Anglo-German ancestry Elizabeth Wiskemann recalled:

On the morning after the German “election” [the Reichstag election of 29 March

1936] I traveled to Basle; it was an exquisite liberation to reach Switzerland.

It must have been only a little later that I met Maynard Keynes at some

gathering in London. “I do wish you had not written that book’,” I found myself

saying (meaning The Economic Consequences, which the Germans never ceased to

quote) and then longed for the ground to swallow me up. But he said, simply and

gently, “So do I.”7

Despite his

undisputed command of economics, Keynes did not pick up that most of the London

schedule was phony money. When, by the second half of the 1930s, it had become

clear that Germany had not been ruined by the Treaty of Versailles but was

recommencing its attempt to take possession of most of continental Europe, he

saw that he had erred, and regretted having written The Economic Consequences

of the Peace.

But America’s default

and British evasion, a true case of Albion perfidy since Lloyd George may have

bamboozled Clemenceau by inserting in the British Treaty of Guarantee the

condition that it would come into force only if the Americans ratified their guarantee

treaty.8 The failure of the two guarantee treaties was to be the cause of a

great deal of trouble in the years following the signing of the Treaty of

Versailles. Ruth Henig 9 quotes FS Northedge who

stated that the effect of the failure of the USA to join the League was “to

widen the gulf between British and French attitudes towards the peace and thus

to contribute to their fatal inability to act together when the great

challenges to the League came in the 1930s”.

In the end all these

men’s individual aspirations and achievements were overborne by events over

which governments and their members had no control: the Wall Street Crash and

the Great Depression that followed it, although the preoccupation of those Governments

with balanced budgets and “sound money” undoubtedly made matters much worse

than they need have been.

The Manchurian

episode and the League of Nations

An important

development, on which I based a recent Seminar in China, took

place in September 1931 on the other side of the world and was the first of

the acts of aggression that were to destroy the League of Nations’ credibility

because it could not prevent or reverse them. On the pretext that Chinese

saboteurs had tried to sabotage a Japanese owned extra-territorial railway that

ran across the province of Manchuria, the Japanese army invaded that province

on 18 September and eventually rechristened it “Manchukuo”.

The source of this

action was the extreme nationalism

of army officers who openly disobeyed the civilian Government in Tokyo. The

Government attempted to control the army and deny the existence of the problem

but the army did not support them: “There now followed weeks of public

embarrassment and secret humiliation for the Wakatsuki Government. While the

army in the field boldly extended the scope of its operations, Japanese

representatives at the League of Nations in Geneva and in Washington, London

and other capitals, declared that these military measures were only temporary

and would soon cease”.10

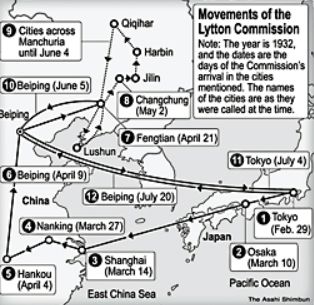

Fighting then spread to

Shanghai and other parts of China. The League sent an investigatory commission

to Manchuria under Lord Lytton to investigate the situation. Meanwhile, the

Government was increasingly discredited internationally because of the “blatant

contrast between Japanese promises and the actions of Japanese troops spreading

fan-like through Manchuria led the world to suppose that the cabinet in Tokyo

had adopted a policy of deliberate chicanery and deceit. This was not so. What

was happening was the breakdown of co-ordination between the civil and military

wings of the Japanese structure of state power.11 When the Lytton Committee

reported it condemned Japan for an act of aggression, although it found many

Japanese grievances to be justified. The Lytton Report was adopted by the

League, “whereupon Japan, much to the private anguish of the emperor, flounced

out of the League”.12

The League of Nations

sought to restrain Japan through sanctions and sought Article 16 intervention but

it was unable to do so because the major power in the Pacific was the USA. She

has always regarded the Pacific rather than the Atlantic as her mare nostrum

but she was not a League member and was not inclined to get involved in taking

action against Japan because of growing isolationist sentiment in Congress and

among the public. Also she was disinclined to put at risk her trade with

Japan.13 The only other Power with major forces in South-East Asia was Britain,

who was also not inclined to use force against the Japanese. Taylor 14

commented that “The only Power with any stake in the Far East was Great

Britain; and action was to be least expected from the British at the exact

moment when they were being forced off the gold standard and facing a contentious

general election. In any case, even Great Britain, though a Far Eastern Power,

had no means of action”. So was executed the first act of naked aggression by

one of the future Axis powers and thus was the frailty of the League exposed

for all to see. The League was similarly ineffective when the Chinese appealed

for help after the Sino-Japanese war broke out in 1937 but by then its

credibility had been further damaged by Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia and

the League’s abject failure to stop it.

Hence by the end of

1931, the European and worldwide situation was looking increasingly unstable,

with the anti-system parties in Germany steadily gaining seats in the Reichstag

and the French unsympathetic to German demands for relief from reparations. And

whereby the above mentioned Reparations Conference at Lausanne which finally

resolved this problem had to be postponed from early 1932 to June and July. The

Japanese invasion of Manchuria was another cloud on the horizon because it was

a grave challenge to the credibility of the League of Nations.

1. Patricia O'Toole,

The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and the World He Made, 2018, p. 384

2. A. Bullock,

Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. Connecticut, 1962, p. 176

3. Richard Bessel,

"Why did the Weimar Republic collapse?", in Ian Kershaw (ed.),

Weimar: why did democracy fail?, pp. 126–27.

4. A. L. Rowse, All

Souls and Appeasement: A Contribution to Contemporary History,1961, p. 110

5. See for example

William R. Keylor, Versailles, and International Diplomacy, pp. 501–02; Also

Stephen Schuker, American "Reparations."

6. Schuker, op. cit., pp. 10–11.

7. Elizabeth Wiskemann, The Europe I Saw, 1968, p. 53.

8. A. Lentin, Lloyd

George, Clemenceau and the Elusive Anglo-French Guarantee Treaty, 1919. In A.

Sharp & G. Stone (Eds.), Anglo-French Relations in the Twentieth Century:

Rivalry and Co-operation (pp. 104– 119). London: Routledge, 2000.

9. R. Henig, Britain,

France and the League of Nations in the 1920s. In A. Sharp & G. Stone

(Eds.), Anglo-French Relations. London: Routledge, 2000, p.147.

10. R. Storry, A

History of Modern Japan, 1963, p. 188.

11. ibid. p. 189

12. ibid. p. 193

13. A. J. P. Taylor,

The Course of German History, 1961, p. 63

14. ibid pp. 62– 63.

For

updates click homepage here