By Eric Vandenbroeck

The Control Of Taiwan

During the Cold War, three groups

dominated elite discourse in Japan. The first was pragmatic conservatives, led by

Yoshida Shigeru, who became mainstream within the LDP and governed effectively

for most of the Cold War. The second was anti-mainstream revisionists within

the LDP, led at first by Hatoyama Ichiro and Kishi Nobusuke, and,

later, by Nakasone Yasuhiro. Both groups of conservatives were confronted by

antimilitarists on the left who wanted unilateral pacifism. By the end of the

cold war, the anti-mainstream Right had accepted many of the constraints

imposed by the pragmatists, while the latter maintained power by pacifying the

pacifists, many of whom were progressive intellectuals who believed the only

threat to Japan was economic. After the Cold War, however, the balance of power

within the conservative camp shifted dramatically, but no group suffered more

than the pacifists. Besides some real 'conspiracy theories' soaked with

Japanese superiority, the one valid point the LDP was able to stress was the

fact of an alleged U.S. financial siege of Japan

"before" Pearl Harbor, mentioned in Japanese textbooks. As we can

show based on documents that have been de-classified 8 to 10 years ago

only, there was truth in that, see also here.

Files of information released by the Americans side

the Holocaust Era Records Act, show among others that from 1937 to 1940 a dozen

experts in U.S. financial agencies analyzed Japan's balance of payments, gold

production and reserves, scrap gold collection, liquidation of foreign

investments, and other financial data. They predicted when Japan would be

bankrupt and have to stop the war in China, always six to eighteen months in

the future. It was a comforting thought to policy makers, but the analyses were

wrong. From 1938 to the summer of 1940 the Bank of Japan secretly

accumulated $160 million in the New York agency of the Yokohama Specie Bank. It

began with funds removed from London. It was a sum equal to three years' oil

purchases from the U.S. The YSB did not report the deposits, as required by

law. Bank examiners discovered the fraud in August 1940. Japan raced to

withdraw the money during the first half 1941. The fraud accelerated thinking

in Washington toward a dollar freeze, instead of commodity embargos, as the

most deadly sanction. The freeze order was drafted in March 1941. As is well

known, It was imposed on 26 July 1941 when Japan occupied southern Indochina.

After the freeze, Japanese diplomats and agents proposed many ideas to unfreeze

dollars in order to reopen trade. Dean Acheson, the effective manager of the

freeze policy, rejected them all. In August 1941 the Japanese government,

through Mitsui, made an extraordinary offer to barter $60 million of silk for

$60 million of US commodities, mainly oil. Barter would not require unfreezing

dollars, they thought. Strangely, they chose as spokesman a Roosevelt-hating lawyer named Raoul Desvernine. Acheson and Vice President Wallace rejected the

scheme on 15 September, about the time the Japanese government was deciding for

war.

Furthermore features

of the prewar situation from records that were not classified but that are

omitted from other history books. thus there are a large number of

vulnerability studies, of Japan's foreign trade written in April 1941 by

committees of trade experts of U.S. agencies under direction of the Export

Control Administration. Reviewing the oil and tanker situation in both Japan

and the U.S. for example one will here find that FDR blamed an imaginary

shortage of gasoline in America as a reason for the freeze of Japan. There was

no shortage despite the loan of 20% of US tankers to Britain. I explain why. I

reviewed Japan's trade with America. Two-thirds of Japan¡'s

dollar earnings were due to exports of raw silk to America. (When war began in

Europe all other currencies became blocked and inconvertible.) The Great

Depression and rayon substitution destroyed the silk dress industry. After 1930

nearly all Japan¡'s silk went for American women's

stockings, which was a strong market despite the Depression. On 15 May 1939,

however, DuPont introduced nylon stockings at the New York Worlds

Fair. They were a great success. By 1941 nylons gained 30% of the market, and

were on track to 100% in 1943 if no war. The market loss of $100 million per

year would have been a disaster for Japan if it had not gone to war. What P.1

of this two part investigation showed is Roosevelt's idea of a financial siege

of Japan in fact backfired by exacerbating rather than defusing Japan's

aggression. And for sure the attack on Pearl Harbor was not the result of a

deliberate Roosevelt strategy (as right-wing conspiracytheorists

claim), but a Roosevelt miscalculation. See Case Study:

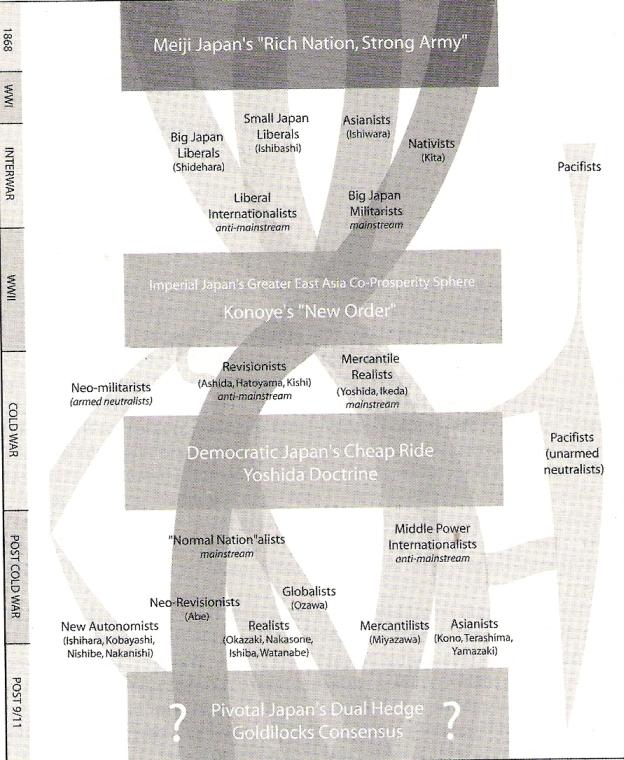

Deep divisions within

the Japanese body politic of the past were reconciled temporarily, first under

the banner of Prince Konoye's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, with

disastrous consequences, and later under the banner of Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru's

Yoshida Doctrine. Today we are witness to an active debate about the value of

the strategic doctrine that contributed so much to postwar Japanese prosperity

and stability. The Yoshida Doctrine has not yet been replaced, but by making

Japan more muscular and by incrementally eliminating many of the constraints on

the use of force, revisionists have made sure that its contours are

definitively changed. Japan's junior partnership with the United States may be

slipping into history. If so, the question is how a more muscular Japan will

position itself. Will it be a fully entangled global partner, or a fully hedged

independent power?

A great deal has

changed since the late 1980s, when Japan was known an economic giant and

political pygmy. Like most historical changes, this one is over determined. It

has been catalyzed by international events beyond Japan's control, by domestic

political struggles, societal change, and institutional reform, and by the

'transformation' of the defense establishment of Japan's alliance partner. I

start this review beginning with four international catalysts, each of which is

connected directly to the first fundamental shift in the global and regional

balances of power since 1945. Together, after a hiccup or two of uncertainty,

these catalysts stimulated Japanese strategists to imagine the transformation

of the domestic institutions of Japanese grand strategy. The first was the

epochal demise of the Soviet Union. With the end of the Cold War, security in

Western Europe walls not only settled, but largely disconnected from the

problems of East Asia. For the first time since the East Asian quadrilateral

was assembled in 1905, the balance of power in the region is being determined

solely by fluctuations among the four powers.

Tokyo's judgment of

what was happening was uncertain, and, as a consequence, its political support

for Boris Yeltsin's reforms was late in coming. Indeed, Japanese statesmen

arrived at the barricades only after Chancellor Helmut Kohl, President George

H. W. Bush, and Prime Minister John Major had already locked arms and pledged

solidarity against the counterrevolutionary Communists. Even then, even after

it was clear that the global security environment had changed, Tokyo had

trouble settling on a strategic direction. All the familiar choices for

achieving autonomy, prestige, strength, and wealth presented themselves anew,

and signs of oscillation between the U.S. and Asia became visible. A decade of

trade friction with the United States suggested to some that this was a chance

to escape from under Washington's thumb. Others justified a new Asianism by

linking regional solidarity to the dramatic rise in Japanese investment in

Southeast Asia after the 1985 Plaza Accord and to the rise of economic

regionalism in Europe and North America. If Southeast Asian leaders such as

Malaysia's Mahathir Mohamad were encouraging Japan to join in a new regional

solidarity, why should Japan not tilt toward a rising Asia and lead it into

prosperity? Why should it continue to hug the United States closely now that

the raison d'etre for the alliance had slipped away?

Two things were

clear: the military balance was shifting rapidly, and Japanese strategists were

not ready. The changes they ultimately made were a matter of slow unfolding

rather than of decisive discontinuity. On the military side, it took a while

for them to appreciate that nothing would ever be the same. When Japan's Basic

Defense Policy was written in 1957-and for the next half century-Japanese

defense policy was Soviet-oriented. Even though the Soviets never really

developed the capability to invade the Japanese home islands, Japan's ships,

planes, and tanks were configured to repel a Soviet invasion from the north.

This exclusively defensive defense (senshu boei) was politically inspired. Force levels were

determined by the need for a balanced posture, a vague term that resulted in a

fixed number of twelve infantry divisions and eight anti-aircraft units

distributed evenly across the archipelago, rather than to optimize resistance

to attack?

The draw down of

Russian forces in the Far East was swift and very dramatic. The Maritime

Self-Defense Force had reported sighting Soviet naval vessels in the Sea of

Japan in 1987, but only nine Russian ships in 1996. No more than 5 percent of

Soviet destroyers remained in the Russian Pacific fleet. The central

justification for the alliance and for Japanese security policy had to be

replaced-and eventually was. After considerable time, debate, and American

exhortation, Tokyo began to shift its military focus from Hokkaido and northern

Honshu, where it had faced the threat of Soviet invasion, southward, where

assets could more easily be deployed against perceived Chinese threats. It

reduced the number of Ground Self Defense Force tanks, improved mobility, and

shifted resources into naval and special operations.

On the broader

strategic front, two major international crises intervened before Tokyo could

conclude that it was unwise to set off on an independent regional security

strategy. These crises, the first in the Middle East and the second on the

Korean Peninsula, did more to transform perceptions than any structural shift

in the military balance. If the end of the cold war was the "big

bang" that changed the global security architecture, the Gulf War in 1991

and the first North Korean nuclear crisis in 1993-94 were catalysts for a

long-sought Japanese awakening to the importance of security. It was not pretty

watching the Japanese government fail miserably in its first test of the

so-called New World Order. At first, it had all seemed so straightforward. Some

in the ruling LOP, led by its secretary-general, Ozawa Ichiro, wanted to

dispatch Self-Defense Forces to the Middle East as part of the multilateral,

UN-sanctioned peacekeeping force being assembled by the United States. Ozawa

and his allies understood the extant ban on overseas dispatch, but they

insisted that this deployment would be consistent with the preamble of the

Japanese Constitution, which acknowledged responsibilities to the international

community. They therefore contrived their own interpretation: "collective

security" (shudanteki anzen

hosho) could cover participation with other states,

and without challenging the ban on "collective self-defense" (shudanteki jieiken).

By the time the Diet

opened on 12 October 1990 to debate dispatch of the SDF to the Persian Gulf,

however, Prime Minister Kaifu Toshiki (the latest heir to the Yoshida mantle)

had grown cautious about this reinterpretation. On that very day Ozawa led a delegation

of top LOP officials to meet Prime Minister Kaifu to propose that the SDF be

permitted to use arms under UN command. The prime minister reportedly responded

by claiming that his hands were tied: "The CLB director general has told

me that this is 'constitutionally impossible.''' N6t surprisingly, this did not

go down well with Ozawa or other senior party officials. They soon left the LOp, after having first sworn a vendetta against

bureaucrats in general and against the CLB in particularly.

For now, though, the

pragmatic mainstream· still enjoyed the upper hand. CLB Director General Kudo

Atsuo declared in the Diet that because the UN's Kuwait-based peacekeeping

force planned for the possibility of violence, its members carried arms and

therefore could not be supported by SDF troops. Although Kudo did allow a

difference between the "use of force" (buryoku

koshi) and the use of arms, a difference that later

would constitutionally justify participation in peacekeeping operations (PKO),

it was not enough for Japanese participation in this warP

In January 1991 coalition forces acted without Japanese support; the CLB even

rebuffed JDA proposals to send transport planes to rescue refugees, on the

grounds that the JDA was authorized to fly overseas only for training purposes.

The U.S.-led coalition in the Persian Gulf was mobilized with $1) billion

raised in a special tax on Japanese citizens but without Japan's physical

presence in the theater of operations. Japan's financial support was not even

acknowledged by the Kuwaiti government. It was not until hostilities had ceased

and the MOFA could declare that sending ships was a matter of

"navigational safety" rather than a wartime deployment, that the MSDF

swept thirty-four mines from the Persian Gulf. This first-ever overseas

deployment of the SDF left the bitter taste of far too little, far too late in

everyone's mouth. In March 1qq1, Ambassador Michael Armacost cabled Washington:

A large gap was

revealed between Japan's desire for recognition as a great power and its

willingness and ability to assume these risks and

responsibilities For all its economic prowess,

Japan is not in the great power league Opportunities for dramatic initiatives

... were lost to caution ... [and] Japan's crisis management system proved

totally inadequate. (Declassified cable from Ambassador Michael Armacost posted

by the Nation~ Security Archives on 14 December 2005 at http://www.gwu.edu/-nsarchiv/NSAEBE

NSAEBB175/index.htm.)

All Tokyo had to show

for having tied itself in knots over participation in the first Gulf War was

humiliation: international criticism of its checkbook diplomacy. Ozawa and his

anti-mainstream allies became more determined than ever to take control from

the weak-kneed mainstream and the CLB. Specifically, they vowed to end the 1955

system that had bogged Japan down just when action was most urgently needed.

They knew that pacifism had become a flimsy shield and that Japan should no

longer expect to get away with international peacekeeping from deep within the

rear area.

If the Gulf War

tested Tokyo's preparedness to be normal, the 1993-94 Korean crisis, Northeast

Asia's first bona fide security crisis after the end of the cold war, tested

its commitment to the alliance with the United States. Once again Japan was not

ready. In 1993 the United States discovered a secret North Korean nuclear

weapons program. After considerable bluster and brinksmanship on both sides,

the Agreed Framework was signed in October 1994 that defused the crisis

temporarily. Japan, the Republic of Korea (ROK), and the United States would

provide heavy fuel oil and lightwater-reactor

technology, and in exchange Pyongyang would freeze and ultimately dismantle its

nuclear program. This did not happen, and neither did the North Korean regime

reform or collapse before the next crisis erupted in 2002. What did come to

pass, however, was the realization that Japan was not prepared to act in

concert with the United States in the event of a military crisis on the

peninsula. Operational plans were limited or nonexistent, and the future of the

alliance was suddenly in jeopardy.

North Korea was a big

problem, but it also was a big opportunity. Its open hostility served those who

sought a stronger alliance and, especially, a stronger Japan. In addition to

stimulating the new alliance framework announced in 1996, Pyongyang tested its

missiles in Japanese airspace in 1998-leading immediately to approval by the

Diet of an intelligence satellite program. In 2001 one of its boats engaged the

Japanese Coast Guard in Japan's first postwar military encounter. It was just

what Japanese defense planners and conservative politicians had been waiting

for. Now they could make their case for new strategic thinking about Northeast

Asian security with a credible threat in full view of the nation. As one JDA

official remarked to Paul Daniels, a U.S. Army analyst, North Korea provided a

reasonable excuse for Japan to expand its military.

In retrospect, then,

it is clear that both crises were functional in ways that the larger demise of

the Soviet Union was not. They catalyzed debate on fundamental issues about

national security and the U.S. alliance. A declassified March 1991 U.S. Embassy

cable lists several that were in playas a direct result of the Gulf War

experience: (1) the continued efficacy of the renunciation of the use of force;

(2) the importance of contributing manpower to the international community in

times of crisis; (3) a more equitable division of roles and missions within the

U.S.-Japan alliance; and (4) the desirability of a more independent foreign

policy. The crisis on the peninsula raised additional issues, such as the need

to upgrade Japanese intelligence and, especially, to enhance interoperability

within the alliance. Together, these incidents drove home to the Japanese

public something they and many political leaders had never wished to believe:

that the world and, indeed, their own neighborhood were dangerous places. They

were learning, moreover, that security was not free, and it might not even be

cheap any longer.

Certainly the United

States was upping the ante, with a good deal of prodding from U.S. alliance

managers. In 1994, for the first time in twenty years, the Japanese government

comprehensively reviewed its security posture and issued a new National Defense

Program Outline (NDPO, or taik. Although it retained

the Basic Defense Force Concept, the new NDPO upgraded the alliance in the

event of a regional crisis. Thanks to the peacekeeping legislation that had

passed in the Diet earlier that year, the new NDPO also added two new missions

to the SDF portfolio: disaster relief and international peacekeeping. At the

time, the new NDPO was celebrated as having broadened the scope of Japan's

commitments, and certainly this was the case when new alliance guidelines were

issued the following year. Now Japan would take fuller responsibility for

defense of the areas surrounding Japan (shahen), a

move that one analyst has called "a significant upgrade of operability in

responding to regional contingencies. But Tokyo insisted on preserving a degree

of strategic ambiguity. MOFA presied the awkward line

that the term "areas surrounding Japan" was "situational"

and not geographical. Some analysts could now insist that the alliance could

enjoy expanded possibilities for joint operations, though most were convinced

that the ambiguity was retained in order to avoid offending Beijing. The

greatest ambiguity remained: Was Japan accepting a U.S.-Japan division of labor

in regional security, or was it avoiding one? Was the Yoshida Doctrine

unraveling, or was it entering a new and more sophisticated phase?

These questions were

being raised just in time for the next major shift in the regional balance of

power-the rise of China. The 1995 NDPO did not mention China as a threat, but

it did touch on nuclear arsenals in neighboring states, and so justified enhancing

forces in the south while cutting two divisions in Hokkaido. The 2004 National

Program Defense Guidelines-NDPG (in English) was the first national security

document to openly identity a potential threat from the People's Republic of

China, noting that the PRC was modernizing its forces and expanding its range

at sea. Tokyo's defense specialists are convinced that China intends to

establish itself as the world's second superpower and are concerned that

domination of Japan will be part of the process. But China's power was shaping

up to be far more complex than the Soviet Union's ever was. China turned out to

be, after all, determined to be rich as well as strong. On the economic front,

the PRC has already established itself as the largest trading partner Japan has

ever had. Japan cannot get enough of the Chinese market or of Chinese goods. In

20°5, bilateral trade exceeded $225 billion, the seventh record year in a row.

Not surprisingly, this has led to a redirection of foreign investment. In the

first few years of the 2000S, Japan reduced direct foreign investment to the

United States by more than half and increased it to China by more than 300

percent. By 2003, China had become responsible for more than 90 percent of the

growth of Japan's exports, and Japanese companies employed more than ten

million Chinese. This is, of course, a mixed blessing for Japan. Many insist

that the two economies are structurally complementary-Japan excels in R & D

upstream and in after-sales service downstream, China provides raw materials,

labor, and assembly skills-but others express serious concerns? China is a

source of Japanese wealth, but it may be using these relationships in a

"rich nation, strong army program of development with unique Chinese

characteristics that could lead to regional hegemony.

Many in Tokyo are

concerned that the Chinese market is luring Japanese firms into complacency

about China's real intentions. Beijing, rightly believe, is merely using trade

with Japan as way to enrich itself so that it can acquire a fuller arsenal. And

even if this is not the case, few senior Japanese leaders are confident there

is stable civilian control of the Chinese military. They focus on the

divergence of national objectives rather than on the economic

complementarities, which they see as temporary. They also focus on the simple

geopolitical fact that no vessel can reach Japan from the south without passing

through the waters adjacent to Taiwan. If China seizes control of Taiwan, they

warn, it seizes control of Japan's sea-lanes as well. This exaggerates Taiwan's

geostrategic importance, but Japanese strategists insist that Chinese control

of Taiwan would enhance China's coercive power. China and Japan are two of the

world's largest energy importers, and they have never been great powers at the

same time. There have been repeated Chinese submarine and other incursions into

the Japanese Exclusive Economic Zone, where the Chinese navy is suspected of

mapping the seabed to deny access to U.S. warships in case of a Taiwan

contingency. Security specialists are also concerned that China is acquiring

missiles for "sea denial" and that the PLA's buildup seems aimed well

beyond any Taiwan contingency. As Beijing has asserted territorial claims and

extended itself in the East and South China seas, Japanese security planners

have accelerated plans for their own force transformation. In fact, China has

supplanted North Korea and has replaced the Soviet Union as the central object

of Japanese security planning.

Meanwhile, a 2005

report of the U.S. Congressional Research Service concluded that China is

supplanting Japan as the leader in Asia. China's rise promises to have enormous

consequences for U.S. power in the region as well. With close to one hundred

thousand troops stationed in Northeast Asia, the United States is still the

preeminent military power and remains committed to a strong presence.(

Testimony Of Admiral Thomas B. Fargo, United States Navy Commander, U.S.

Pacific Command, before the House Armed Services Commity

' United States House Of Representatives, Regarding U.S. Pacific Command

Post 31 March 2004.) Nevertheless, decreasing U.S. participation in

emerging regional economic institutions and a planned transformation of

overseas troop deployments together suggest decreased American influence in the

region. Although the United States increasingly depends on Asian finance and on

commodity trade, an Asian regional trade and financial system has emerged

without U.S. leadership or, in some important cases, even without U.S.

participation. It was clear by 2004, when Beijing took the diplomatic lead away

from the United States in the six-party talks, that the United States no longer

had the ability to disarm North Korea peacefully without Chinese support.

It was clear that the

bipolar balance of the long postwar era had long since given way to a brief

unipolar moment," after which U.S. dominance was challenged by China, by

the Europeans, and by non-state actors around the world. Suddenly, the terms of

ideological conflict had shifted from arguments about capitalism and

authoritarianism to arguments about theocracy and secularism. National arsenals

that had bristled with conventional arms and strategic nuclear weapons had to

be reconfigured to enhance communications and control; the great powers could

no longer count on proxies to fight their wars; and direct deterrence could no

longer be their core strategy. For the United States, this meant force

transformation. For Japan, this meant that planners no longer had the luxury of

focusing on Soviet conventional warfare, which had always been a low

probability event. Now they had to contemplate missile attacks by the

Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), terrorist attacks at home, and

Chinese coercion on the high seas-all of them lower intensity but higher

probability events. Whereas security once had meant averting great power

conflict, now it involved deterring regional conflict and minimizing

casualties. Japan is no longer a simple cog in an anti-Soviet deterrent, and it

has had to recalculate the prospect that the United States might not stand by

its side indefinitely. Now it has to cope with Chinese economic power while

defending its territorial claims and contributing to global public goods with

more than cash. Japan was expected-and became determined-to contribute

positively to the stable functioning of the international security environment.

To do this, the SDF had to begin functioning as a modern armed force.

Japan's strategists

know this and are well aware that their military transformation lags far behind

the U.S. one. As one U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) official noted publicly

in 2005, it still was not even clear if Japan could even plan for a military

contingency.37 Japan's China strategy is inchoate at best, with the economic

relationship running hot and the political one running cold. The service

branches have acquired new capabilities (Japan has even elevated its Coast

Guard to near service branch status), but they have not been integrated under a

joint command. Intelligence remains underdeveloped, and for some roles and

missions the Japanese military is not yet capable. Still, the Japanese defense

establishment is in the midst of significant change, much of which has been

enabled by changes in the domestic political environment.

These changes are of

three varieties: sociological, ideological, and institutional. None is the

direct result of shifts in global or regional balances of power, and each is

related to domestic political competition. The most prominent sociological

change has been in the status of the Self-Defense Forces. Although Japanese

remain more likely than any other people to insist that they would not take up

arms even to defend their homeland, and although some question the willingness

of even the SDF to engage in war fighting, the forces' status has never been

higher. Fifteen years after the end of the Pacific War, the SDF were barely

accepted as a necessary evil, and in 1973, James Auer reported that the

Japanese military was still not a respected profession.

When SDF personnel

express a desire for higher status in society, their referent is the citizen

soldier of normal nations rather than the samurai, the imperial servant of the

past. To the contra~ Japanese soldiers today seem eager to disassociate themselves

from their imperial predecessors and to show to the Japanese population, to our

neighbors, and to the international community that we have changed. Their

effort to depict the new Japanese military as warm and fuzzy and their embrace

of liberal values, such as democracy and civilian control, is evident

everywhere, from the recruiting manga produced by the MOD public relations

officials to the curriculum of the Defense Academy.

A second sociological

change has been generational. The percentage of young people holding a

favorable impression of the SDF has never been higher. At the time of the Gulf

War in February 1991, less than 57 percent had a favorable impression. In

February 2006, just five months before the GSDF troops were withdrawn from

Iraq, more than 81 percent held a favorable impression. Those whose impression

is unfavorable fell sharply, from 31 percent to just 13 percent in the same

period. Recruitment, which is made more difficult by the sharp decline in the

population of eligible males, is assisted by the newly positive image of the

SDF. A generation gap within the political class also is emerging. In November

2001,167 conservative young Diet members crossed party lines to create the

Young Diet Members' Group to Establish a Security Framework for the New

Century. Led by Ishiba Shigeru of the LDP and Maehara

Seiji of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), the group made up nearly

one-quarter of the Diet and nearly half of all members born after 1960. Rather

than focus on their elders' traditional issues of defense technology, budgets,

and equipment procurement, this group urged Japan to "defend its national

interest based upon 'realism' . They insisted that Japan get to work on a grand

strategy and even discussed such topics as maritime resources in the East China

Sea-including drafting legislation outside normal channels. Internal

party organs such as the LDP's Policy Affairs Research Council, which had been

instrumental in tying politicians and bureaucrats together on defense policy

issues, were being openly supplanted by new forms of interparty policy

coordination-led by forty-something’s.

Within the LDP,

meanwhile, a separate intergenerational power play was under way that led to a

new party-and national security-strategy. After a decade of failed efforts by

Ozawa Ichiro and others to wrest power from the LDP mainstream, anti-mainstream

conservatives within the party used shifts in regional and world politics to

seize power from within. In 2000, Koizumi Junichiro (whose father had been a

defense minister), Abe Shinzu (whose grandfather,

Kishi Nobusuke, had been an architect of the Manchurian occupation), and other

direct heirs to the anti-mainstream agenda gained control of the LDP and,

thereby, of the Japanese government. They immediately set to work to transform

the institutions of national security policymaking. They had the unqualified support

of young conservatives with considerable expertise in security affairs, such as

Ishiba Shigeru-not to mention the support of the

United States. The rise of a new generation of revisionists was surely the most

consequential political change in Japan since 1945.

Their first target

was to establish firmer political control over the bureaucracy and they did so

by elevating the policy role of the Prime Minister's Office (Kantei). In an unprecedented assault on the prerogatives of

elite bureaucrats, in 2001 three major changes were made. The first

strengthened the agenda-setting power of the prime minister and increased the

institutional resources available exclusively to him. The second reformed the

structure of the Cabinet Secretariat; and the third established the Cabinet

Office (Naikakufu). Now the prime minister can submit proposals to the cabinet

on basic principles on important policies" without having first to secure

broad ministerial support. Because these basic principles include a wide array

of national security policies and budgetary powers, the Japanese prime minister

has never been more presidential. Moreover, the number of special advisers and

private secretaries available exclusively to the prime minister has expanded,

and the authority of the Cabinet Secretariat to draft policy, as well as to

coordinate policies from the line ministries and agencies, has also been

enlarged. The secretariat is responsibly to the cabinet but also serves as a

direct advisory body to the prime minister and is "in charge of final

coordination at the highest level. By the end of 2004 fifteen offices within

the Cabinet Secretariat bore responsibility for policy development across a

wide range of issues. Whereas the number of staff in 1993 had been under two

hundred, by 2004 the total was closer to seven hundred. This bulking up of the

Cabinet Secretariat altered the balance of power between the ministries and

between the government and the LDP's policy organs. So did the creation in

January 2001 of the Cabinet Office, which absorbed the former Prime Minister's

Office and several other units, including the Defense Agency. Now the prime

minister had the power to establish ministers for special missions, and they

can request materials from the line ministries and report directly to the prime

minister.

These reforms have

resulted in a significantly more flexible policy apparatus and stronger

executive leadership, thereby reducing government response time during crises.

They were put in motion before the Koizumi team took office, by Ozawa Ichiro

and Hashimoto Ryutaro, for whom security was only one of many reforms. But the

first palpable changes came after September 11, 2001, when Prime Minister

Koizumi moved with striking speed to craft Japan's response to U.S. calls for

support in the 'war on terror.' Koizumi established within the Cabinet

Secretariat the ad hoc Iraq Response Team (Iraku Mondai Taisaku Honbu), which he chaired. He assigned a small group of JDA

and MOFA officials to Assistant Cabinet Secretary Omori Keiji to develop a new

law to enable SDF deployment. In early April 2002, the group reported that

existing UN resolutions would be insufficient to justify SDF deployment under

the existing Peacekeeping Operations Law. Koizumi ordered that a new law be

drafted. This legislation, invoking UN Resolution 1483 as the legal basis for

action, would restrict SDF operations to noncombat zones and avoid any review

of existing restrictions on the use of force-or even any mention of Article 9.

Despite high levels of public opposition and bureaucratic doubts-and despite

the cavalierly tautological way in which Koizumi defined noncombat zones as the

area where the SDF is operating, the SDF dispatch was swiftly enacted. It is

hard to interpret this as anything less than a turning point in postwar

Japanese security policy. As the chair of the LDP Policy Committee on Foreign

Affairs insists, "the power of the bureaucracy is decreasing and political

leadership is increasing.

Not all

branches of the bureaucracy were hurt equally by these reforms. The JDA

actually benefited. Until the mid-2000s, Japanese security policy had been

managed chiefly by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Koizumi years have been

a traumatic time for the MOFA. As the role of the Cabinet Office expanded, an

increasing number of officials were seconded from the JDA-twice as many in 2005

(more than sixty, including ten military officers) as in 1995. Three deputy

cabinet secretary posts were established, one each allotted to foreign affairs,

finance, and defense, putting the JDA on an equal footing with MOFA for the

first time. Much to the chagrin of Japan's professional diplomats, negotiations

with the Pentagon over U.S. force realignment in 2006 were led by the JD A and

not by MOFA, as was customary. When he became prime minister in September 2006,

Abe Shinzo's first act was to further remodel the Kantei

in the image of the White House. Within months he also saw to it that the JDA

would become the MOD. (New York Times, 27 September 2006.)

The trimming of

bureaucratic prerogative and the rebuilding of bureaucratic powers continued

with the second major institutional change, a frontal assault on the power of

the Cabinet Legislation Bureau. As we have seen, the CLB had long played a

central role in managing the Yoshida Doctrine. The problem, from the

perspective of the anti-mainstream conservatives, was that these officials had

worked closely with their political overlords in the LDP mainstream to keep

security policy under wraps. In their view, the CLB had usurped the

politicians' role in civilian control of the Japanese military. In addition to

defining "war potential" (senryoku) so

narrowly in 1952 that Japanese forces have been hamstrung ever since, the CLB

could declare collective self-defense (shiidanteki bOei) unconstitutional, both of which infuriated the

revisionists. And they had long been apoplectic over the CLB's tortured May

1981 interpretation of Article 9, which recognized Japan's right of collective

self-defense but declared its exercise forbidden. When the CLB (again with

political approval, of course) dug in its heels during the debate over response

to the Gulf War in 1991, making it impossible for the SDF to be dispatched

until after the war was over, the newly ascendant revisionists vowed to make

changes. And they did.

First, though, their

like-minded, sometime ally, Ozawa Ichiro, forced the issue. In August 1999,

when he demanded fuller control of the CLB as the price for bringing his

Liberal Party into the governing coalition, the CLB director general with whom

he had had contretemps on the Diet floor was forced to resign and his

successors were barred from answering Diet interpellations on behalf of cabinet

ministers.65 Prime Minister Koizumi brought the CLB-and the rest of the

bureaucracy-under further political control. Although the CLB was not

eliminated, it was forced to conduct its business on a very short political

leash, its non-congenial interpretations left unsolicited. The same CLB that

ruled in 1996 that it is problematic to amend the law to enable the prime

minister to control and supervise the ministries and agencies-even during an

emergency" now was more fully controlled than ever. It stood aside as the

revisionists made the prime minister presidential. In this way, Japanese

politicians took a giant step toward reconfiguring civil-military relations.

The CLB was not the

revisionists' only target. Koizumi's team also vowed to go after the councillors (sanjikan) within the

JDA. Director General Ishiba insisted that the

(mostly younger) politicians who understood national security issues should

assume control of the defense establishment and must no longer rely on the

councilors as their proxies. He also elevated the status of the senior military

officers in each service branch, making them the equivalent of the councilors.

Prime Minister Koizumi told me, he explained, "that 'politicians need to

be able to argue with bureaucrats.' This was a major change. The bureaucrats

learned that they can no longer expect ministers who know nothing. Civilian

officials predictably developed an Ishiba strategy

and dug in and waited for Ishiba's term to end. But

the writing was on the wall, and the civilian bureaucrats had lost considerable

ground. In addition to the long-standard posting of junior lawmakers to each

ministry as parliamentary vice ministers to educate them about policy issues,

the Koizumi team appointed senior politicians as vice ministers to give

politicians even further supervisory influence in the policy process. In the

JDA, it would be difficult to confuse bureaucratic control with civilian

control any longer, especially after January 2007 when it became a full-fledged

ministry.

The revisionists also

brought along a Japanese press that had always reflexively invoked fears of

militarism. Even the Asahi Shimbun begafl to publish

positive accounts of the SDF, including for the first time interviews with

uniformed officers. One Asahi senior staff writer went even further, insisting

"there is no more likelihood of resurgent militarism in Japan than

"there is of the reintroduction of slavery in the United States, or of

further seizure of Mexican territory." (See the Asahi editorial of 8 June

2003 and the Mainichi editorial of 16 June 2003, both written while the

emergency legislation was under consideration in the Diet.)

When it was learned

in 2004 that the U.S. military and the SDF had produced an annual coordinated

joint-outline emergency plan from 1955 to 1975 to unify the military command in

an emergency-and that the plans were kept secret from the prime minister the

public could barely stifle a yawn. The very legitimacy of the Japanese military

is no longer in question, and concerns about civilian control have receded.

Yamagata's ghost had been shoved into the shadows, surely one of the greatest

changes since the Pacific War.

Another change, was

the transformation of the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) into a de facto fourth branch

of the Japanese military-may be the most significant and is certainly the least

heralded. The Japan Coast Guard Law was revised by the Diet at the same time

that the more prominent antiterror legislation authorized the dispatch of ships

to Diego Garcia. Unlike the MSDF dispatch to the Indian Ocean, which was

limited to the supply of fuel for U.S. and British troops, the Coast Guard Law,

as amended, allowed the outright use of force to prevent maritime intrusion and

to protect the Japanese homeland. Now the Coast Guard-still legally a law

enforcement agency" within the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and

Transport and not part of the JDA except in an emergency-is assigned rules of

engagement more relaxed than those of the SDF. Local commanders are authorized

to use force under the conditions of justifiable defense and during an

emergency (kinkyu). Warning shots, if ignored, can be

followed by disabling fire targeted on the offending vessel's propellers in

order to disable it. Within one month, in the first Japanese use of force since

the end of the Pacific War, Prime Minister Obuchi ordered the Japanese Coast

Guard to fire upon a North Korean vessel, which, unmarked and refusing to

identify itself, was known as a mystery ship (fushinsen).

The DPRK vessel reportedly scuttled itself in the Chinese Exclusive Economic

Zone to avoid capture. Fifteen North Korean crewmembers were killed in the

firefight.

Those who guided the

development of the Japan Coast Guard vigorously deny this, insisting instead

that the new, improved JCG (the English rendering of the name was changed from

Maritime Safety Agency in April 2000) is merely a long overdue modernization,

"changing an analog JCG into a digital one. They maintain that while

militaries fight one another, coast guards enforce laws and are partners in

crime fighting?9 Still, using the term for "war potential" (senryoku), which was declared unconstitutional in Article

9, the JCG White Paper headlines the ICG's New Fighting Power and trumpets

repeatedly its expanding security role. It explicitly lists securing the safety

of the sea-lanes and maintaining order on the seas alongside rescue,

firefighting, and environmental protection as core missions. In April 2005,

Prime Minister Koizumi visited Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in New

Delhi, and the two governments announced their Eight-fold Initiative for

Strengthening Japan-India Global Partnership, specifying enhanced security

cooperation on a sustained basis between the nations' navies and coast guards.

Insisting that the JCG is not a fourth branch of the SDF, it is Japan's first

line of defense, serving as a litmus paper for MSDF action. And that the MDF

and the JCG coordinate more closely than ever before. Certainly, the

reinvention of the Japan Coast Guard was politically expedient. Mainstream

politicians and political parties (including both the Komeito

within the ruling coalition as well as the opposition Japan Communist Party)

that would not abide increased defense spending were more than willing to

increase maritime safety and international cooperation. No doubt because the

JCG is described as a police force, rather than as a military one, these

distant deployments have ruffled few feathers at home or abroad. To assure that

a benign view of the JCG persists, the Japanese government has tied it to its

foreign aid program. It is now routine for the JCG to assist Southeast Asian

states with training and technology to help them police the Strait of Malacca

and other areas along the Middle East oil routes. Month-long conferences on

maritime safety attended by coast guard officials from members of the

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are funded through the Japan

International Cooperation Agency, Japans foreign aid

agency. Agency funds set aside as antiterrorism grant aid were also used to

provide the Indonesian and Philippine coast guards with three fast patrol craft

each in 2006. Because these ships were equipped with bulletproof glass, they

were classified as weapons by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry

(METI), but because they were unarmed and were supplied to a coast guard, the

Japanese government claimed it was ;not violating its arms export ban.

The most recent

institutional change is the most arresting. Revision of the U.S.-imposed

constitution-the holy grail of antimilitarism-is once again in play. Indeed, it

is closer to realization than at any time in the past sixty years. Picking up

on a shift in popular sentiment after the Gulf War-indeed, capitalizing on

generational change and unprecedented public acceptance of the SDF-revisionists

began to paint Article 9 as an obstacle to international cooperation. They

launched a sustained effort to make the constitution conform to international

standards they considered normal. Revisionists secured several major

legislative victories in the 1990s, including the establishment of Diet

research commissions that issued final reports in April 2005. They were also

joined by influential new allies in the media and academia. Years before the

LDP's first draft, the Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan's largest daily newspaper,

drafted a constitution that would specify the right of collective self-defense.

Japanese universities continued to employ academics advocating pacifist

positions, but the new generation includes more scholars favoring a change in

Article 9 than was the case in the 1950s. By the end of the decade, revisionist

support and accomplishments had accumulated. The Self-Defense Forces and Coast

Guard were able to engage in a growing list of widely accepted activities once

deemed unconstitutional, and the LDP and the Democratic Party of Japan, the

major opposition party, were both positioned to support constitutional

revision. It looked ever more likely that the constitution would be revised to

acknowledge that Japan has a legitimate military and can legally engage in

collective defense. Once again, Yoshida Shigeru may have been prophetic. In his

memoirs he had defended opposition to revision of Article Nine but allowed that

"obviously there exists no reason why revision should not come in the long

run [so long as the Japanese people are] watchful and vigilant. ... The actual

work of revision would only be undertaken when public opinion as a whole has

finally come to demand it.”

After the end of the

cold war-and after serial encounters with North Korea, in particular-Japanese

public opinion shifted dramatically. the positive impression of the SDF grew in

nearly a straight line from the mid1970s, according to Cabinet Office polls.

The SDF benefited from successful PKO missions to Cambodia and Mozambique, as

well as from positive press related to its operations in disaster relief. In

fact, the majority of Japanese polled between 1997 and 2003 believed that

disaster relief was the top mission for the SDF, a result belying the

impression that the Japanese public was embracing a national security mission.

After all, the public preferred that SDF capabilities be expanded but was

expressing heightened concern about Japan's being drawn into war. The sticking

point was cost: the number of Japanese willing to increase the defense budget

had risen but remained at barely 10 percent in 2003. Attitudes toward the

United States and the alliance were stable and mostly positive, while those

toward Russia remained stable and entirely negative. Apart from volatile

attitudes toward China and both Koreas, the biggest change in public opinion

regarding security issues in the past decade and a half has been support for

revision of the constitution. Depending on the poll and the question, support

for constitutional revision in general first exceeded opposition in the early

1990s (Yomiuri Shimbun) or a few years later (Asahi Shimbun). By April 2005,

those who supported and those who opposed revision of Article 9 were in a

statistical dead heat. The Japanese public had come a very long way. The United

States was cheering these changes, but not from the sidelines. For decades it

had pressured Japan to play a more active military role even while it kept

Tokyo on a short leash. But Japanese strategists had proclaimed their pacifism,

and the asymmetry in the alliance remained acceptable to both sides because

their interests were so closely aligned. Indeed, after a decade of trade

frictions had threatened to destabilize the security relationship, it was the

U.S. side that relaxed pressure on Japan. President Clinton and Prime Minister

Hashimoto reached an agreement in April 1996 that reinforced the alliance and

reassured the allies.

But these dynamics

changed after 9/11. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld announced plans for U.S.

"force transformation" in November 2001, signaling a more flexible

global posture. Within two years, it was clear that the formal alliances of the

United States could be supplanted by more informal coalitions of the willing,

as in Iraq. The message was not lost on the Japanese. One ASDF general, Marumo

Yoshinari, observed that the United States was now marketizing its alliances,

countries could buy a place by contributing to mutual security. Some Japanese

grew as concerned about entanglement as they were about abandonment. The Asahi

Shimbun concluded that "without its being seen by the public, the cold war

U.S.-Japan alliance is being replaced by the unification (ittaika)

[of U.S. and Japanese forces]." Would the SDF become a fifth branch of the

U.S. armed forces? If so, would it be forced to undertake operations beyond the

defense of the main islands?

After the GDSF was

withdrawn from Samawah Province in Iraq, the ASDF was tasked with supporting

U.S. troops in Baghdad. A major daily immediately suggested: "Transporting

U.S. Troops May Drag the ASDF into America's War." How could Japan avoid entrapment

in U.S. wars? (See the debate in the December 2004 issue of Sekai: "Anzen Hosh6 Seisaku no Dai Tenkan

ga Hajimatta" (The Great Change in the National

Defense Policy Has Started), 77-92.) The predominant view-expressed by

government officials and analysts alike-was that Japan's "near

irreversible dependence" on the United States forced security planners to

hug the United States more closely than ever and, if necessary, to be prepared

to shed blood. (Tokyo Shimbun, 19 July 2006.)

This decision has not

come cost free. No matter how much the Japanese were prepared to increase their

contribution to the alliance, it was never quite enough. Some Japanese believe

they have had to play catch-up to U.S. demands, whereas the U.S. Department of

Defense was convinced that the alliance has been playing catch-up to changes in

the global security environment. U.S. officials called on Japan to create a

more balanced, more equal, more normal defense relationship. Their exhortations

prompted one U.S. observer to suggest that "the only thing that has risen

faster than the level of cooperation between our two nations during the

Bush-Koizumi era has been the level of Washington's expectations. Predictably,

there were consequences. Japanese scholars and analysts wondered aloud where

Japanese national interests are located in the U.S. global agenda. Others

pointed to the low (and decreasing) level of public support for U.S. foreign

policy. In 2005, a majority of Japanese believed that Japan should cooperate

with Washington in world affairs, but more than half also did not trust the

United States and an equal number believed that U.S. forces should leave Japan.

U.S. force

transformation, combined with the palpable threat from Pyongyang, provided

Japanese revisionists with a long-awaited opportunity to enhance SDF

capabilities. The U.S. force transformation made it more acceptable to discuss

the need to recognize the right to collective self-defense. Abe Shinzo made

this a top priority during his campaign to become prime minister in 2006.

(Yomiuri Shimbun, 23 August 2006.) Even revision of the Mutual Security

Treaty was back on the table. The real challenge was for Japan to learn how to

judiciously utilize the power of the United States, and its main challenge was

to find a way to manage American hegemony. ("Judiciously utilize" is

from National Institute for Defense Studies 2003, 23, and "jointly manage"

is from Taniguchi 2005, 45.)

Many in the Japanese

security community welcomed U.S. pressure for this very reason. They were eager

to move from the principle of passive alignment that guided the Yoshida

Doctrine to an active alliance relationship. U.S. demands factored into

Japanese plans for expanded roles and missions as a new division of labor (yakuwari buntan) was constructed.

Tokuchi Hideshi, an author of the 2004 NDPG, insisted

that since the alliance is "indispensable" for security in Asia,

Japan's new strategy should acknowledge the need for "shared

understandings of the new security environment" and the establishment of

"common strategic objectives." (Tokuchi

quoted in Securitarian, March 2005,13-14.)

After three years of

DoD pressure-in the form of a Defense Policy Review Initiative that sought a

shared assessment of strategy and threats as well as a common assessment of the

roles and missions required to meet them-the Japanese government formally signed

on to an explicit set of common strategic objectives in February 2005. This

overhaul created as many options for Japan as it foreclosed. The press focused

on shared bases, but Japanese defense officials avoided endorsing the idea of

joint commands. Former JDA director general Ishiba

Shigeru warned that Japan must not get caught in America's wake, and explicitly

ruled out the possibility that the SDF would ever become part of the U.s. military command. Japan, rather, would become a

cooperative, equal partner of the United States because it is in Japan's

interests to do so. But adding new missions to the alliance also enhances

Japan's ability to act outside the alliance should it choose to do so. The

alliance and cooperation are formally reaffirmed at every turn in official

documents, but opportunities are seldom lost inside Japan to assert that Tokyo

has many security challenges, one of which is the need to rediscover the

ability to make its own decisions.

*The label ‘Yoshida

doctrine’ was coined in 1963 when its core ideas came to be embraced across the

board as Japan consensus view of its national security identity. It started

with Shigeru Yoshida making sure that the ex-officio members of the National Security

Council (Kokubo Kaigi) were limited to cabinet

ministers and that former flag officers were explicitly barred from posts in

the new Defense Agency in 1954. Later, as prime minister, Kishi tried a

different tack-he sought to upgrade and reorganize the Defense Agency. But this

initiative also failed, as the uproar over the Security Treaty in 1960 made

defense policy nearly untouchable. His successor, Ikeda Hayato, a mainstream

Yoshida pragmatist, made sure that the issue did not return to the Diet. Like

the successful doctrine of the Meiji oligarchs and the unsuccessful doctrine of

Konoye, the Yoshida consensus was built on a profoundly realist understanding

of international affairs made operable by the consolidation of domestic power.

Strategists saw that the cold war made Japan as important to the United States

as the United States was to Japan, and that the nominally weak partner could

also become rich and strong. The Yoshida Doctrine borrowed considerably from

the past. Its mercantile realism was focused on generating wealth and

technological independence per the ‘rich nation, strong army’ doctrine, but it

eschewed the military. Like the Toyo Keizai editorialists in 1915 who saw no

profit in Japanese possession of China, the Yoshida mainstream understood that

aggression would stimulate balancing behavior and would close markets. They saw

clearly the benefits of cheap riding. The Yoshida mainstream opportunistically

embraced the pacifist Left in order to keep the anti-mainstream at bay, and the

anti-mainstream eventually came around to accept the central tenets of the

doctrine.

For updates

click homepage here