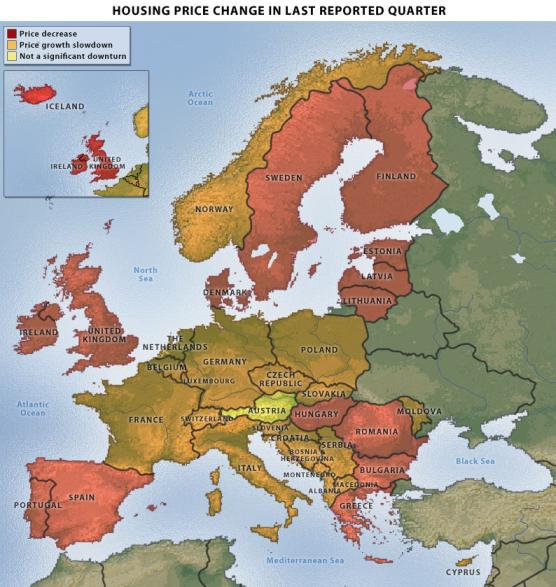

Especially in the emerging markets of the Baltic states, Central Europe and the Balkans, the problem is already severe.

In 2006 and 2007, the Baltics saw average house price increases of more than 20 percent, dwarfing price increases in the rest of Europe (indeed, the world). The housing boom in emerging Europe was also fueled by an influx of cheap credit, particularly through the foreign-currency lending policies of foreign banks that rushed into the region.

Especially active were Italian, Austrian, Swedish (in the Baltics) and, to an extent, Greek banks, which saw an opportunity in emerging Europe to carve out empires away from powerful competitors in Western Europe. However, they still had to overcome the problem of luring consumers to purchase mortgages from them, especially since interest rates in emerging Europe were considerably higher than those in the eurozone.

To overcome this problem, the foreign banks used Swiss franc- and euro-denominated loans. A form of lending perfected in Austria (mainly due to its close proximity to Switzerland), foreign-currency-denominated lending meant allowing consumers in one country to borrow in the currency of another. Essentially, mortgages, consumer loans and commercial loans were denominated in low-interest-rate Swiss francs and euros and serviced in customers’ home currency. The low interest rate brought with it the risk of currency fluctuation and added a level of variability to the loans. The Austrian and Italian banks acted as middlemen, making loans in Swiss francs to lend to consumers in Central Europe (particularly Hungary, Romania and Croatia) to buy homes. However, those consumers paid back the loans in their own currency. The price for the low interest rate was therefore the risk that the Hungarian, Romanian or Croatian currency would fall against the value of the loan. So long as these states were riding the rising tide created by the road to EU membership, this was at worst a distant concern.

But with the global credit crunch and impending recession, many Central European and Balkan economies have indeed seen their domestic currencies fall precipitously against the Swiss franc and the euro. Consumers who took out foreign-currency-denominated mortgages are therefore staring at a dangerous appreciation in the value of their loan, and thus the size of their monthly payments. A homeowner in Hungary, for example, is dealing with a 16 percent decrease of the value of the forint against the Swiss franc just since August. Consumers in Hungary, Romania and across Central Europe receive wages in their domestic currencies, so they are staring at a dangerous combination of already-increasing mortgage payments due to currency fluctuations and likely drops in the value of their homes as the crisis bites.

The situation is particularly dire because of the extent to which foreign-currency lending was practiced by foreign banks in these markets. In Hungary and Croatia, more than 80 percent of all consumer loans since 2006 have been denominated in foreign currency; in Poland and the Baltics, the figure hovers around 50 percent; and in Romania, it is over 60 percent. If Central European currencies continue to decline against the euro and the franc, the bulk of the mortgages made in foreign currencies could become unserviceable and in essence turn into something worse than “subprime” despite never having been targeted or labeled as such.

The threat of defaulting mortgages and of unfavorable lending conditions inevitably will force banks to raise the cost of lending, either by asking for larger down payments or by eschewing foreign-currency lending altogether (the latter has already happened in recent days across Central Europe and the Balkans) — or both. This will have the effect of pushing potential customers (the young and the poorer consumers) out of the housing market, dulling demand considerably, creating a pool of unsold inventory and seriously crippling housing prices in the long term.

The United Kingdom

And emerging Europe is hardly the only place outside the eurozone facing a potential housing meltdown. The United Kingdom, home of the region’s biggest housing bubble, is staring at the potential abyss of its housing market. The U.K. housing bubble has created a housing price increase not matched by increased wages; home prices in the United Kingdom have risen to nine times the average household salary (higher than even the U.S. housing bubble increase of six times the average salary). In the climate of ever-increasing housing prices, British banks sought to lure young and first-time buyers by offering variable rates (over 90 percent of all mortgages in the United Kingdom are variable rate) and allowing no-down-payment options (for example, 100 percent mortgages). Put simply, the vast majority of U.K. mortgage loans of late are precisely the sort of loans that caused the U.S. subprime/mortgage crisis; mass defaults are all but inevitable.

The magnitude of the problem in the United Kingdom is reflected in how London has reacted to the global credit crunch so far. The total government rescue plan is well over 530 billion pounds (nearly US$900 billion, or almost 50 percent of the United Kingdom’s gross domestic product, GDP, dwarfing the United States’ $700 billion bailout package which is just 5 percent of U.S. GDP). Most of the bailout is meant to loosen interbank lending and to keep consumer interest rates as low as possible. In fact, the government sought guarantees from banks it directly intervened in (Royal Bank of Scotland, HBOS and Lloyds TSB) that they would specifically relax mortgage lending. The bailout plan, announced on Oct. 8 and Oct. 13, was followed by a dramatic (and record) 1.5 percent interest rate cut on Nov. 6, indicating, in a way, that the government is not comfortable with relying solely on the direct liquidity injections into banks.

Problems in the Eurozone

Within the eurozone, the notoriously overheated housing markets of Ireland and Spain have actually been crashing for some time now. The Spanish decline began in first quarter of 2007 when housing sales dipped by 32 percent, creating a cascade effect in the construction industry and rising unemployment figures. Similarly, Irish house prices have fallen by 9.2 percent in April 2008 compared to the previous year and have already created a surplus housing inventory of more than 200,000 vacant homes, representing more than 15 percent of the total national stock.

Ireland’s and Spain’s housing booms — but also those of Italy and Portugal — are correlated to their entry into the eurozone. With the adoption of the euro came low consumer interest rates (compared to what these countries had previously) backed by robust German economic power. The euro’s introduction increased stability and lowered currency risk, bringing the stability of the deutsche mark to even the most fiscally unstable (think Italian lira or Spanish peseta) corners of the eurozone. The euro-backed interest rates — combined with new lending instruments developed throughout the 1980s and 1990s in retail banking — led to a boom in consumer demand that fueled the housing boom. In 2006, Spain in fact built 700,000 new homes — more than Germany, France and the United Kingdom combined (for Spain and Portugal the boom was further fueled by capital-rich retirees from the United Kingdom buying retirement property).

This, however, led to a serious “price gap” across the board (defined by the International Monetary Fund as the percent increase in housing prices above what can be explained by sound economic fundamentals such as interest rates or increases in homeowner wealth — thus a calculation of the extent to which the housing prices are inflated above the economically justified price). The problem was not confined to the above-listed economies. As lending rules were loosened in most of Europe, the housing boom became a continent-wide phenomenon. Only Germany, with its extremely conservative mortgage qualification programs — most borrowers need to prove their creditworthiness by maintaining an account with a potential lender for years in order to qualify for a mortgage loan — appears immune.

Liberal lending policies in Spain were also fueled by the government looking to integrate its large Latin American immigrant population; credit checks were often simply waived. Consumers in Spain and Ireland gorged on variable-rate and no-down-payment mortgages. In Ireland, many even took out mortgages of 125 percent of the total loan, thus getting some extra “start-up” cash to refurbish the home or purchase new appliances, further stimulating consumer spending and artificially spiking prices. As the current global credit crunch has affected Europe, many of these banks have been tightening their lending rules. Unfortunately, this may be a panicked move that comes too late, and that further exacerbates the crisis as it will further dampen demand and make the ongoing price corrections that much more brutal.

Under normal circumstances, many of these states would have simply raised interest rates to prick their housing bubbles — higher credit costs would have slowed the market down — but that is no longer an option. Membership in the eurozone means that the European Central Bank (ECB) sets a country’s interest rates, not that country’s government. The ECB sets rates with an eye toward German inflation levels, not Irish or Spanish levels. This does more than simply remove a tool from the economic toolbox; it vastly delays policy adjustments, adds more updraft to prices and makes the inevitable crash that much harder.

The Long-Term Outlook

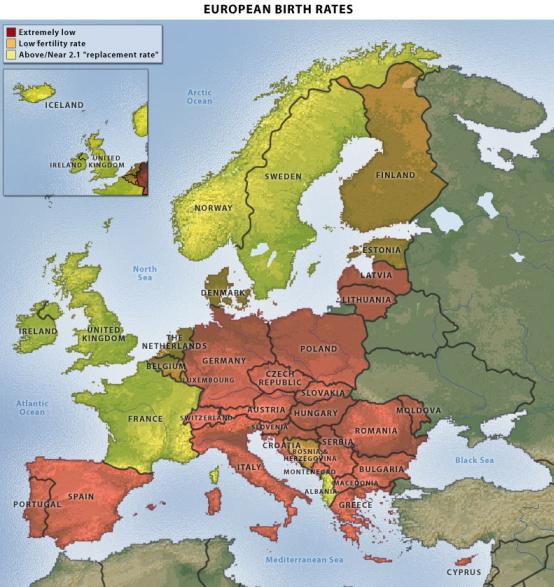

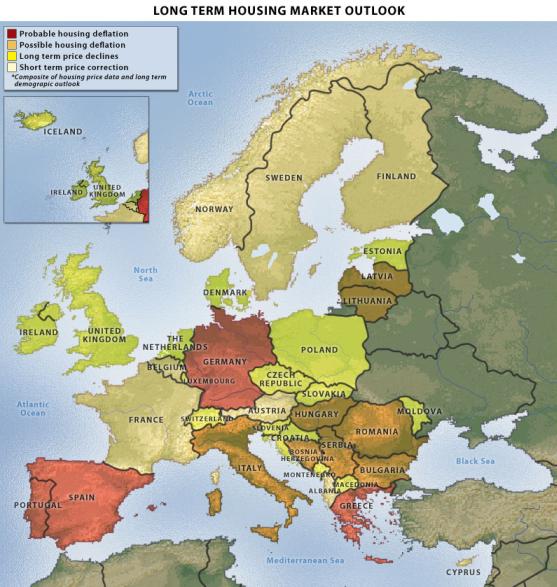

A longer-term problem for the eurozone — and Europe in general — is the continent’s poor demographic situation, which will inevitably have an adverse effect on housing prices. For the housing market to have sound fundamentals, there must be strong and sustained demand for housing. The simplest way to guarantee that is to ensure long-term population growth.

Yet the European Union’s birth rate is but 1.5 births per woman, well below the “replacement rate” of 2.1. Compounding the demographic problem is the ever-rising life expectancy across the region that contributes to an increase in older residents. This will create considerable problems for the labor pool and increase the burden of taxation to prop up European social welfare systems. At the same time, it will dampen the demand for housing in the long term and possibly create a deflationary spiral in the housing market.

In Western Europe, this problem is further compounded by the fact that credit-rich retirees have fueled housing booms elsewhere, particularly in Spain, Portugal and Bulgaria. For the moment, this trend will stop, as the credit crunch makes lending anywhere — but especially in the shakier corners of Europe — problematic. Nonetheless, if the trend restarts after the credit crunch is over, Western Europe will face a further decline in demand as retirees move abroad, leaving behind a glutted housing market to be filled by a shrinking number of young first-time buyers. Simply put, the structural factors alone will dictate that housing prices in many regions will have nowhere to go but down.

Which does not let emerging Europe off the hook. It will take years before the poorer parts of emerging Europe — primarily the Balkans and Baltics — can develop to the degree that serious domestic demand will justify broad homebuilding exclusively on domestic fundamentals, without the boost granted from foreign-introduced credit. By the time the poorer portions of emerging Europe become that rich, their demographics will have soured sufficiently that there may well not be the population necessary to create a housing boom in the first place. The picture for the richer states of emerging Europe — primarily Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic — is somewhat brighter. They set off on the road to economic growth several years earlier, and are far more likely to see purely domestic housing booms before the demographic problems truly bite.

Regardless, in deflating market conditions, banks will have to tighten lending even further as they will essentially be granting loans for assets that they know will become less valuable over time. While this is normal for car loans, mortgages have far lengthier terms — and the odds of the lender getting stuck with a defaulted loan, now backed by a depreciating asset, are high indeed. As banks increase lending rates and credit criteria to insure against this risk of depreciation, demand for houses will further decline as first-time buyers and young families are squeezed out of the market. The result? A self-reinforcing deflationary spiral in the housing sector.

Demographics in Europe are a long-term trend that will not — indeed, cannot — be reversed any time soon. To maintain a 3-to-1 ratio of labor force to retirees (considered necessary to fund the national welfare projects) the European Union would need an influx of more than approximately 150 million new migrants between 2000 and 2050 in light of its endemic low birth rates. It is highly unlikely that Europe will be able or willing to sustain such an influx of migrants.

![]()