A flurry of meetings is taking place as stakeholders in the Syrian

conflict attempt to work out a power-sharing agreement to replace the

government of Syrian President Bashar al Assad. Russia has been driving the

negotiation, while Oman acts as a neutral mediator relaying messages to and

from Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Russia and the United States. Though

the diplomatic activity is picking up, it is still an outside effort divorced

from the reality of the battlefield, where Syrian rebels are fighting the al

Assad government on their own terms.

Following a trip to Tehran, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem,

who has been leading the negotiations on behalf of the al Assad government,

traveled to Muscat, where he met with his counterpart, Yusuf bin Alawi bin

Abdullah. Though Saudi Arabia has preferred to keep these negotiations more

private, the Syrian government is eager to telegraph its involvement in such

meetings to boost its legitimacy after years of diplomatic isolation.

The discussion between al-Moallem and

bin Alawi allegedly centered on an exit strategy for al Assad. The Syrian

government knows that proposing elections in which al

Assad runs is a non-starter for negotiations with the Sunni powers, but al

Assad is still angling for a graceful exit. Negotiating amnesty for al Assad

will be a challenge, however. It is still unclear just how flexible the United

States will be on the subject, especially with charges against al Assad pending

over his government's use of chemical weapons and other war crimes. Syria has

signed but not ratified the International Criminal Court's Rome statute, the

founding document for the International Criminal Court, which means the country

falls outside its jurisdiction. Unless a future Syrian government ratified the

Rome statute or somehow accepted the court's authority, the only way the ICC

could bring suit against Syria would be if the United Nations Security Council

referred the case to it. However, this is unlikely as long as Russia retains

its veto power, which will come in handy during amnesty negotiations. The

possibility of a subsequent government charging al Assad in the ICC will also

complicate where he can take refuge as part of any deal.

Meanwhile, the dialogue over the political transition continues. Iranian

Foreign Minister Javad Zarif will head to

Turkey on Aug. 11 and then to Moscow later in the month. Russia will also host

another round of talks with the highly fragmented Syrian National Council

opposition coalition. Multiple factors have been speeding up negotiations:

loyalist forces in Syria are suffering setbacks, the United States is trying to

avoid a power vacuum in Damascus, and Russia is trying to strike a diplomatic

win over Syria. Our assessment remains, however, that these negotiations are

largely disconnected from the reality on the battlefield. Sunni rebel forces

have the momentum in the fight and are unlikely to agree to a deal at this

stage, much less cede power to controversial Sunni figures such as Tlass who

have lived comfortably in Paris while others continued the fight in Syria. For

this negotiation to yield an effective outcome, it will be vital that Syrian

rebel factions get involved.

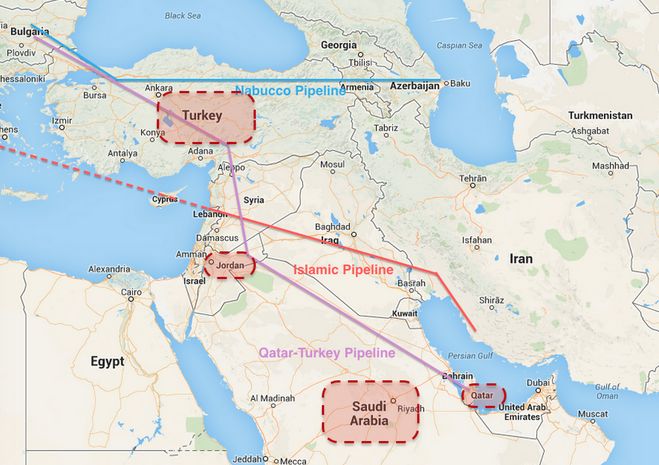

Briefly mentioned by me before, there is also the Qatar pipeline which is of strategic

importance in what now is the ISIS theater.

Fighting on the ground seen

problematic for Damascus

Two ongoing offensives in Syria, staged by Jaish al-Fatah and the

Islamic State, are problematic for Damascus as it scrambles to contain multiple

threats. Loyalist forces are spread thin across many fronts but still doggedly

attempting to defend their positions and mount counterattacks.

Having largely secured Idlib province, Jaish al-Fatah is now channeling

its efforts into pushing down through the strategic Sahl al-Ghab

plain corridor in northwest Hama province. Securing the plain would improve rebel

access to Latakia province while positioning them for a combined assault on the

rest of Hama province alongside other rebels positioned close to the town of

Morek.

Against considerable loyalist forces massed on the Sahl al-Ghab plain,

supported by large numbers of artillery and armored units, fighting has

devolved into fluid battles comprising numerous attacks and counterattacks. The

overall advantage lies with the rebels, who are adept at using the heights

around the plain to their advantage, relying heavily on anti-tank guided

missiles to neutralize the government's superiority in armor. Over the last 48

hours, the rebels succeeded in taking the village of Bahsa,

and are moving towards Joureen. If they can maintain their

progress and take Joureen itself, the rebels would be able to largely isolate

the remaining loyalist forces, essentially securing control over the plain.

Meanwhile, the Islamic State capitalized on its inherent mobility and

staged a successful surprise offensive, seizing the crossroads town of al-Qaryatayn, not far from Homs. The Islamic State is

attempting to hold off a loyalist offensive to take back the ancient city of

Palmyra. The militant group's offensive on al-Qaryatayn

fundamentally undermines the loyalist advance toward Palmyra by hitting the

outer lines of Damascus' forces on the flank and threatening essential supply

lines feeding the loyalist advance. With al-Qaryatayn

taken, currently the loyalists only have access to one road to reinforce their

vital T4 Airbase and support the push on Palmyra.

Conclusion

The flurry of diplomacy suggests that Russia and the United States,

whose differences have long jammed efforts to resolve the conflict, are making

newly concerted strides toward goals they have long claimed to share: a

political solution to Syria’s multisided civil war and better strategies to

fight the Islamic State.

Of course Assad is

not yet ready to leave, and the rebels may not be in the mood for a compromise

agreement even if he does. But for the first time Moscow, and possibly Tehran,

seem willing to talk about the idea, and even Assad is prepared to listen.

He would require

amnesty from being prosecuted at an international court. This week’s UN Security

Council vote agreeing to investigate the use of chemical

weapons in Syria potentially complicates matters, but exile in Russia or Iran would

still be an option. Syria has not ratified the charter of the International

Criminal Court and so falls outside the ICC’s

jurisdiction.

If the outline of

such a compromise could be worked out there would still be the problem

of who in the Syrian regime would remain to share power with the rebel

groups during an interim phase before some sort of election years down the

line.

All the above is

complicated enough, but would be rendered meaningless if the rebel groups

refused to co-operate and demanded outright victory. However, if the different

sides’ various backers can be persuaded a deal is for the best, the rebels

could be brought round with reminders of who it is that arms, trains, and funds

them.

There would still be

the problem of what to do about ISIL and other international jihadist groups in

Syria. However, if the other rebels were only fighting on one front, and what

support the jihadist groups receives dried up, the rebels would over time be

victorious.

There’s a long way to

go. If this month’s tentative negotiations are not derailed then talks can

continue in the autumn when there is always a flurry of diplomatic meetings

culminating in the United Nations General Assembly where, for a week, all the

main players are in one place at the same time.

The idea may not

survive until then, the battlefield may make it irrelevant, but right now, the

vague outlines of a new effort to end the Syrian war are emerging.

For updates

click homepage here