By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Chinese Nationalist Kuomintang

And Its Relation To Communism Part Two

The new alliance was

sealed at the first Congress of the Kuomintang, which opened in Canton/Guangzhou on 20 January 1924. Although the

official tally of the Chinese Communist Party members amounted to less than 10

percent of the Kuomintang, they provided twenty-three of the 165 delegates who

attended the sessions. Borodin had been part of the commission that had drawn

up its program between late October and mid-January. This was seen as a major

statement of intent: an attempt to shift the party away from the personal forms

of authority which characterized Sun’s leadership to a more formal, statist

administration.1 The meeting exposed cleavages within the Kuomintang. These

came to be understood in terms of the Kuomintang ‘right’ and the Kuomintang

‘left,’ labels which were in many ways adopted by outsiders to make sense of a

very fluid situation and complex moral and intellectual journeys.2 But they

were also taken up as cudgels by the main protagonists themselves. In the

center of the Kuomintang ‘left’ was Wang Jingwei. On the first scrutiny, his

revolutionary credentials were unimpeachable: he had been an adjutant to Sun

Yat-sen during his years in Southeast Asia after 1905. He had attempted by his

own hand to assassinate the Qing prince regent in 1910. During a second sojourn

overseas after 1912, Wang was active in France's anarchist work-study movement,

although he himself did not live as a worker. His experience of the Great War

left him with a deep mistrust of militarism and a belief in ‘human

co-existence.’ Wang was naturally inclined to scholarship more than politics

but was pulled into the latter’s epicenter by Sun Yat-sen on his return to

China in 1919.3 In his stay overseas; he had married the daughter of a wealthy

merchant of Penang, Chen Bijun, who bore him six

children, the eldest two having been born in France. It was said in

Canton/Guangzhou that everyone in the city walked on rubber soles from her

trees, and many mistrusted his professed ‘socialist credentials.’4 But Borodin

and his allies now relied on them for the success of their strategy.

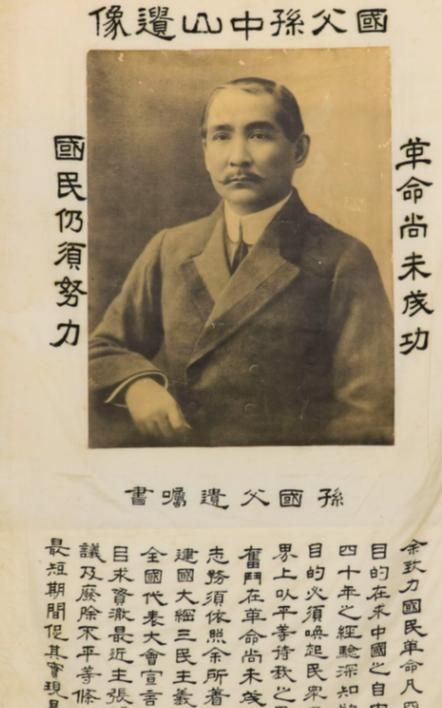

Above Sun in the 1910s

Tensions surfaced at a

celebratory banquet on the very first evening of the Congress, when a

Kuomintang delegate demanded that if the communists were sincere, they should

leave their party. Li Dazhao attempted to reassure

the conference that ‘we join this party as individuals, not as a body. We may

be said to have dual party membership.5 But they were largely seen as

subordinates, and in an early session, when Mao Zedong and Li Lisan began to

speak, many Kuomintang veterans ‘looked askance … as if to ask: “where did

these two young unknowns come from? How is it they have so much to say?”6

On 25 January, Sun

Yat-sen, again with Borodin (Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg) at his side, dramatically took to the

Congress stage to announce that Lenin had died on 21 January. Sun delivered an

emotional eulogy. The conference was adjourned for three days, and the city was

decked in mourning. A wave of grief swept through Asia. Moscow's affiliates

were not brought into being but was something spontaneous, embraced by declared

communists and non-communists alike. Across India, newspapers repeated the

refrain, in the words of a Hindi paper of Allahabad, that the ‘world’s greatest

man of the age has passed away from this world.’ M. Singaravelu, who formed the

Labour Kisan Party in India, led a week of mourning:

‘by his death workers of the world lost their great Teacher and Redeemer.’ It

also revived the comparison with Gandhi, who was still in a British prison, and

the question of violence. For some, the contrast had diminished, as one

Kannada-language account put it: ‘Lenin hated violence as much as Gandhiji. But

he did not believe in licking the hand that holds the sword like a coward.’ For

others, Lenin had died a true sanyasi.7

In Moscow, Nguyen Ai

Quoc queued for hours in Red Square finally to see the great man; Quoc’s toes,

it was said, were permanently blackened by frostbite. In December 1923, he had

settled into the Hotel Lux. He was becoming better known in Comintern circles

but complained of sharing a small room with four or five others and campaigned

for separate quarters for Asia's leaders. But nearly four years from the first

debates on the ‘National and Colonial Questions’, there was impatience at the

lack of progress made in communicating with the human masses of Asia. As Quoc

told the Fifth Congress: ‘I am here to continuously remind the International of

the colonies and to point out that the revolution faces a colonial danger as

well as a great future in the colonies.’ He laid out figures to convey its

scale, for populations, investments, acres of lands in North Africa, equatorial

Africa, Madagascar. He lambasted the European parties for their lack of action

on the colonial question: comrades who ‘give me the impression that they wish

to kill a snake by stepping on its tail.’8 He was increasingly impatient: he

had, he said, been nine months in Moscow and six of them waiting. Then he was

told to join Borodin, who was ‘an old Bolshevik versed in the ways of the

underground’.9

The Expected Next World Conflict

Ten years after the

war outbreak in Europe, there were many signs that the next world conflict was

coming. But it was to be unleashed at a moment when the revolutionary tide in

the west was ebbing, and its field would be Asia. At the anniversary of the February

revolution, Zinoviev reminded his audience that: The revolution will turn from

a European revolution into a world revolution only in the measure that the

hundred million human masses of the East will rise. The East is the main

reserve of a world revolution … The proletarian revolution is aiming first of

all at English imperialism.10

He returned to this

theme throughout the year. At the Fifth Comintern Congress in July 1924, he

stated that the Treaty of Versailles and the last imperialist war was pregnant

with a new imperialist war’.11 The bunds and bridges that marked the limits of extraterritorial

privileges for foreigners in China had become the front line for the assault on

the empire. When, on 19 June 1924, Pham Hong Thai threw his bomb into the Hotel

Victoria's dining room in Shamian, the city of

Canton/Guangzhou came out on strike against the entire European community.

Perhaps it could have happened anywhere, but in these months, it was

Canton/Guangzhou that took on a special band of revolutionaries from all

nations. One of them was a Korean former anarchist known as Kim San, who had

embraced communism during a sojourn in Beijing. To Kim, the veteran Bolshevik

was ‘a rock in a wild sea of inexperienced youth and enthusiasm’.12 The frenzy

of life in the city was fuelled by the expectation

that Sun Yat-sen would commit to the launching of a great northern expedition,

to cut his way out of the southern enclave and reunite China.

It was, in the words

of one Indian writer, an ‘ecliptic time.’13 A foretaste of this came with

the arrival, in April 1924, of the poet and sage Rabindranath Tagore. He had

been invited by the Beijing Lecture Society, presided over by the reformer and

intellectual Liang Qichao, following its earlier hosting of the philosopher's

John Dewey and Bertrand Russell. Tagore’s pan-Asian, spiritual cosmopolitanism

was confronted with a new mood and by a new generation. Many Chinese

intellectuals of the reform and May Fourth eras had drawn inspiration from

Tagore at some point in their lives. Chen Duxiu, for instance, had translated

some of his verse. But the protests were led by a younger group of

intellectuals, many recently returned from Japan and exposed to anarchist

thought there, for whom the generation of May Fourth already seemed distant and

aloof. Guo Moruo was a returnee who had studied for many years in Japan in the

Medical School of Kyushu Imperial University and married a Japanese woman. An

avid reader of Spinoza, Goethe, and Tagore, he had abandoned medicine for

literature and, on his return to Shanghai, had, with kindred spirits, formed a

‘Creation Society.’ It challenged the older generation’s near-monopoly on the

printing presses – the influential Commercial Press controlled 30–40 percent of

the city’s literary output at the time – and championed a new, socially

engaged, internationalist style. ‘If you are sympathetic with revolution,’ Guo

wrote, ‘the works you create or appreciate will be revolutionary literature,

speaking in the name of the oppressed class.’14 Guo Moruo had devoured and

translated Tagore as a student in Japan, but now, as he told it, his evolving

responses to Tagore were stations on his journey towards materialism: ‘My

spiritual ties with Tagore were snapped … I thought Tagore was a nobleman, a

sage, and I was an ordinary mortal of little worth. His world was different

from mine. I had no right to be there.’ With Tagore’s presence in China, there

was a danger that the youth might be similarly seduced by his reification of

the ‘oriental’ and distracted by his spiritualism.15

Tagore reached Hong

Kong in early April 1924. Sun Yat-sen invited him to Canton/Guangzhou through a

messenger, but Tagore, traveling behind schedule, pressed on to Shanghai and

Beijing. Few questioned Tagore’s anti-colonial credentials. In Shanghai, he criticized

Britain’s continued deployment of troops from India in China.16 But Tagore’s

visit to the last emperor, Puyi, further antagonized his critics in the

Forbidden City. There was growing mistrust of the motives of his hosts. Lu Xun,

who heard him speak in Beijing, satirized their wearing of ‘Indian caps’ on the

stage: they treated Tagore as if he was a living god.’17 In Hankou, Tagore was

met with shouts and placards at a lecture outside the Supporting Virtue Middle

School: ‘Go back, a slave from a lost country!’ ‘We don’t want philosophy; we

want materialism!’ He left acknowledging that the gulf between him and his

audience was unbridgeable.18 The worries that Tagore’s spiritual passivity

would seduce a new generation in China proved unfounded. An opinion poll was

commissioned of students at Beijing University, and 1,007 responded, 725 of

whom favored ‘people’s revolution’:

In the coming months,

many of these university students made their way to Canton.

At the center of this

was the foundation, with Soviet money, of a military academy at Whampoa, some

miles south of the city. It was to provide an independent military cadre for

the Kuomintang, as had been urged by Sneevliet and

others from the outset. Still, it also became a means for its commandant,

Chiang Kai-shek, to cultivate his leadership style, as he emerged as the

leading force within what was an increasingly militarized regime. Chiang was a

strong believer in the discipline and rigidity that military training provided.

But physical resilience was insufficient, and an important function of Whampoa

was political education. It was a measure of the ideological fluidity when the

first classes began in June 1924; one of the commissar-instructors in political

economy was Zhou Enlai, who had returned from the communist organization in

France. Soviet advisers also led classes. These included around twenty-five

Koreans and between ten and fifteen Vietnamese, and recruits also came from the

Chinese night schools in Malaya and Singapore. The academy was a forcing-house

for bodily discipline, revolutionary élan, and personal networks: the

‘Intimacy, Fraternity, Dexterity, Sincerity’ of its motto. Chiang Kai-shek took

his maxim – ‘the lives of all the cadets at Whampoa are ultimately one life’ –

as a license to cultivate men whose loyalty would be to him. A high number of

the first cohort of recruits came from Shanghai, through Chiang’s connections

with the city’s business elite and the criminal underworld.20 Meanwhile, Zhou

Enlai created a caucus of military officers loyal to the Chinese Communist

Party. This emphasis on leadership training went further than previous

experiments in Asia, such as the Tan Malaka schools. A Peasant Movement

Training Institute was also set up in July in Canton in an old Confucian temple

with thirty-eight students, mostly from Guangdong, and led by Peng Pai. Over

the next two years, this Institute would educate over 800 peasants from

increasingly further afield, many coming from the mines of Anyuan,

and they gained practical experience in the Guangdong countryside.21

Tan Malaka had

arrived in Canton in December 1923, after a long, clandestine journey that

sowed the seeds of a vision of the unity of the maritime world of Asia. On his

journey into European exile, bullied by drunken Dutchmen, the Chinese sailors

on board his ship had stepped in to protect him. They were followers of Sun

Yat-sen; they knew his situation and shared his views. These solidarities now

helped him move freely across Asia. They were also at the heart of the sojourns

of his own people, the Minangkabau, in the largeness of the world, across the

Indian Ocean, to Ceylon and Madagascar: ‘Guided by the moon and the stars,

sailing in their tiny boats, they were protected by their wits, and their

spirit of community and mutual co-operation in both good times and bad. And

even the ocean became only a lake in their eyes.’22 Now he gave the vision a

name, ‘Aslia’: a nation for the peoples without a country, within a new

socialist world system. In Canton, he was put to work with the seafarers.

Reasonably fluent in the lingua franca of the Comintern in Europe, German, he

possessed neither of the common tongues of radicalism in Asia, Chinese and

English. For his propaganda work, he adopted a kind of ‘basic English’ with a

limited vocabulary of some 800 or so words, which he later conflated with the

pacifist C. K. Ogden’s global interlanguage, which was to be brought to China

by I. A. Richards, a fellow of Magdalene College, Cambridge, in 1929.23 His

journal, The Dawn, was produced by a Chinese printer with no knowledge of

western languages and, Tan Malaka complained, with insufficient Latin type for

the task. Despite his work with the seafarers, he was out of touch with events

in Indonesia, and, in the relative extremes of the climate in southern China,

his tuberculosis worsened. An Indonesian visitor, his only contact with home

for an entire year, found him bedridden in an ‘outlying quarter’ of the city.24

But his major achievement came in June 1924, in the first Pan-Pacific Labour Congress in Canton. For the first time, it brought

together Asia’s global waterfront, sailors and dockers fanning out from China,

Japan, Singapore, Malaya, Indonesia, Siam, the Philippines, and India in

intricate cross-cutting webs, re-energizing links that stretched across the

Pacific.25

he entire

seaboard of Asia seemed about to catch fire. In the middle of 1924, a reported

twenty-eight pirate gunboats were roaming the water approaches to Canton, and

most of the tow-boats to delta ports such as Dongguan and Xiangshan had stopped

sailing.26 To the north, fighting threatened the river and rail connections of

Shanghai: the ultimate prize of the north's warlords, not least because of the

profits of the drugs trade. In August 1924, the Huangpu River was vulnerable,

and the foreign powers determined to bring in their own warships. A flotilla of

several nations anchored off the bund and a military cordon was thrown around

the city beyond its treaty borders. Fighting itself – and the press-ganging of

labor – reached the Chinese city, and by the end of September there were

perhaps half a million Chinese refugees in the International Settlement;

masterless men and women roamed the surrounding countryside and spilled into

the city, 8,000 or so of them occupying the railway carriages and waiting rooms

of the Northern Station. In December, fighting erupted again; much of the

country around Shanghai was ransacked, and violence and looting once more

spread into the suburbs. Like the bomb thrown at M. Merlin, it brought the

brutal reality of war to the doorsteps of the privileged foreigners.27

On 12 November 1924,

a flurry of letters from Canton to Moscow announced another new arrival. He

wrote to apologize for his sudden departure from Moscow and gave his new

address as the Soviet news agency's office, ROSTA. He swiftly ensconced himself

in the Borodin House. He used the identity of Ly Thuy, feigned a Chinese

ethnicity, and sometimes wrote under the pseudonym of a woman, but concerned

himself principally with the Vietnamese communities in the city. ‘I haven’t

seen anyone yet,’ he complained. ‘Everyone here is busy about Dr. Sun going

north.’28 It took a couple of months before the French Sûreté

confirmed that Ly Thuy was indeed their old quarry, Nguyen Ai Quoc.

The same evening

there was a military parade to bid farewell to Sun Yat-sen, as he left Canton

to resolve the Chinese revolution's fate. He went at the northern warlord's

invitation, Feng Yuxiang, whose forces had seized

Beijing the previous month. One of Feng’s first acts was to remove the titles

and privileges of the imperial families, of the last Qing emperor,

eighteen-year-old Puyi, and to evict him from the Forbidden City, where he had

lived in seclusion with a diminishing retinue of eunuchs and tutors since the

fall of the dynasty in 1912.29 For Sun, this seemed to open a path for him to

regain the national pre-eminence he had lost in his wilderness years of exile

and isolation in the south. Of late, he had become impatient with the ‘radical

drift’ of Canton politics, and his mind turned towards the higher arena. In

September, he left Canton for Shaoguan, on the border

with Hunan province, to prepare for a new expedition to the north to unify

China. His plans stalled when his commanders were slow to rally to him. Chiang

Kai-shek believed the position in Canton itself was not secure enough to allow

this. Now, Sun stopped only briefly back in Canton as he left to achieve by

diplomacy the ‘great central revolution’ that he had failed to achieve by

arms.30 As Sun passed through Shanghai, the local leaders

of the Kuomintang organized clamorous civic receptions. His insistent

anti-imperialist message and his call for a new national assembly caught the

popular mood. It seemed that he might regain the momentum to restore past

glories and the presidency of the republic.31

The predestination

air intensified when, between Shanghai and Tianjin, Sun made a short visit to

Japan. In a speech at a girls’ school in Kobe on 28 November, he invoked the

vision of pan-Asianism first raised by the exiles in

Japan twenty years earlier: the call for solidarity between peoples suffering

the same sickness of imperial domination. Those who had taken a stand against

the empire during the world war – men such as Rash Behari Bose and Prince Cuong

De – still lived in exile in Japan, awaiting their hour. The horrors of the

Great War had undermined faith in western ‘civilization’ and its claims to

universal standards among European and Asian intellectuals. ‘Asianism’ revived

as a counterweight to its materialism and rapacious violence.32 But Sun Yat-sen

had always put the struggle for China first. In his Three Principles of the

People, written after the first Kuomintang Congress in 1924, Sun warned that

‘the European idea of cosmopolitanism is but the doctrine of “might is right”

in disguise,’ and therefore ‘unless the spirit of nationalism is

well-developed, the spirit of cosmopolitanism is perilous.’33 He seemed

to place his faith in the ‘universalism’ of Chinese thought – its historical

traditions of peaceful reciprocity – and distance himself from his earlier

declared affinity for western socialism.34 His attacks on British imperialism

electrified his Japanese audience. But in Kobe, in his peroration, Sun also

questioned his hosts' motives: ‘Will Japan become the hunting dog of the Western

Rule of Might or the bulwark of the Eastern Rule of Right?’ These last words

were redacted in many Japanese newspapers, as Sun’s ideological legacy became

contested on all sides.35

For months there had

been rumors of Sun’s failing health. Many of his key aides, including his de

facto deputy in the south, Hu Hanmin, counseled

against Beijing's journey. They feared it was a trap to confer recognition on

his northern warlord rivals at the expense of Sun’s own claims to lead China.

Many of his allies on the left were opposed to negotiating with warlords,

however patriotic or progressive their professed intentions. Sun’s generals had

yet to achieve a monopoly of force within Guangdong’s own borders. There was a

long and bitter standoff in Canton itself between government forces and the

so-called ‘paper tigers,’ the mercenary militias employed by the city merchants

to protect their fortified warehouses and break strikes. When their ability to

import arms was obstructed on 10 October 1924, fighting broke out, and some

3,000 houses and shops – according to the Electric Company's estimate – in the

traders’ district to the west of the old walled city were left in flames.

People who tried to escape were shot at from the rooftops. Refugees fled into

the western concessions on Shamian Island. From

behind its defenses, the cries of those caught in the flames could be heard

through the night. Perhaps 200–300 merchant volunteers were killed and 100

soldiers, many shot for looting. The civilian death toll was unclear. The city

merchants never forgave Sun. He was, one Chinese newspaper cried, ‘bringing us

all to our destruction.’ As a foreigner who witnessed it commented, ‘I am

convinced that it will be impossible for Sun Yat-sen ever to return here.’36

In Sun’s absence,

Canton was threatened by a fresh offensive by Chen Jiongming

from the east. Sun ascribed both crises to the machinations of the foreign powers.

His government survived in no small part under its ability to mobilize the

cadets training at Whampoa Military Academy. In 1925, around 2,500 graduates

passed through its gates, many of them to fight alongside Soviet advisers in

the breakout spring ‘eastern expedition’ against Chen Jiongming.

These cadets gathered valuable war booty and vital experience of using

political propaganda to enlist farmers and laborers as guides, spies, and

porters.37 The Soviet advisers, of whom there were around forty by this time,

we're transfixed by a looming power struggle within the Kuomintang. They

complained of Chiang’s increasing hauteur, his temper, procrastination, and

evasiveness. But they had little reason to doubt his commitment to revolution.

When Mikhail Borodin was asked by one of his subordinates, ‘How far will Chiang

Kai-shek go with us?’, he replied: ‘Why shouldn’t he go with us?’38

On Sun Yat-sen’s

arrival in Beijing on 31 December 1924, his old friend, Beijing University

president, Cai Yuanpei, turned out the student cadets

to escort him in triumph from the railway station, attended by the

representatives of some 500 civic associations. But, in a twist of fate, Sun

was taken seriously ill in Tianjin. His condition worsened a few days after he

arrived in Beijing, and he moved from the Hôtel de Pékin

to the Rockefeller-funded Peking Union Medical College Hospital. A small circle

of advisers closed around him, led by Wang Jingwei, who traveled as his

secretary, Borodin, who had journeyed separately to join him in Beijing. The

communist's Li Dazhao and Zhang Guotao.

As Sun ebbed in late February 1925, a political will was drafted by Wang

Jingwei, with a ‘letter of farewell’ to the Soviet leadership pledging

alliance, approved by Borodin. They were the only two aides allowed at his

bedside. With the help of Sun’s wife, Soong Ching-ling, the letters were signed

by Sun on 11 March, together with a will bequeathing his property to her. Sun

died the next day. The documents named no successor. Sun was not a ‘party’

leader in any conventional sense, but the embodiment of a revolution; nor,

despite Borodin’s best efforts, was the Kuomintang yet a fully formed

‘political party’ in the Bolshevik image.39

Sun’s prestige soared

on his passing: there were solemn vigils in cities across China in which

emotions blended with rituals from Lenin's new cult.40 Sun asked to be buried,

like Lenin, close to the people, and a bronze and crystal glass-fronted coffin

was ordered from Russia. A plan to requisition the Hall of Supreme Harmony

within the Forbidden City was quietly dropped. Instead, Sun lay for three weeks

in Beijing’s Central Park, adjacent to Tiananmen Square. When the coffin

arrived, it proved to be inadequate manufacture of tin and glass, and Sun’s

embalmed body was laid to rest in a simple wooden casket. The private funeral

ceremony – amid further controversy – was a Christian service, insisted on by

the American-educated Soong Ching-ling, and featuring Sun’s favorite hymn:

‘Abide With Me.’41 His body was then laid in the Temple of the Azure Clouds in

the Western Hills, along with the empty tin casket. As with Lenin, news of

Sun’s death was a catalyst to grief across the globe: he was the ‘father of the

nation,’ and, together with Gandhi, the best-known face of Asia. As Tan Malaka,

a witness to this in Canton, observed, before Sun’s passing, many in the city

had called him an ‘empty cannon’: ‘it was really only after he had died that I

saw respect and even praise given to Dr. Sun.’ Tan Malaka had met Sun when he

first arrived in the city. He could not subscribe completely to Sun’s vision,

especially his Marxism critiques and his lifelong faith in Japan as the ‘light

of Asia.’ But he admired Sun for his perseverance, the awareness that there

would be constant reversals on the path to revolution, and, above all, as a

fugitive who had many “strategies” and who had friends everywhere’.42 In the

Netherlands Indies, there were memorial services in Semarang, Surabaya, and

Bandung, attended by Javanese and Chinese. After speeches celebrating Sun and

Lenin's friendship, the government forbade a similar demonstration of

solidarity in the capital, Batavia.43 In Singapore, mourners converged on the

‘Happy Valley’ amusement park in Tanjong Pagar, where the Prince of Wales had

opened the Malaya-Borneo exhibition three years earlier. Over two days, an

estimated 100,000 people filed past 2,000 commemorative scrolls and a

life-sized portrait of Sun. This was almost on the scale of the crowds in

Beijing itself. The British saw this as an insidious challenge to their

authority.44 Even the quietest corners of colonial Asia felt the impact of

these events.

1. George T. Yu,

Party Politics in Republican China: The Kuomintang, 1912–1924, Berkeley,

University of California Press, 1966, pp. 171–5.

2. A point made by

Michael G. Murdock, ‘Exploiting Anti-Imperialism: Popular Forces and

Nation-State-Building During China’s Northern Expedition, 1926–1927’, Modern

China, 35/1 (2009), pp. 65–95.

3. For this see Zhiyi

Yang, ‘A Humanist in Wartime France: Wang Jingwei during the First World War’,

Poetica, 49 (2017/18), pp. 163–92.

4. Vera Vladimirovna

Vishnyakova-Akimova, Two Years in Revolutionary China, 1925–1927, Cambridge,

MA, East Asian Research Center, Harvard University, 1971, p. 206.

5. Pantsov, The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Revolution, p.

64.

6. Zhang, The Rise of

the Chinese Communist Party, p. 332.

7. Devendra Kaushik

and Leonid Mitrokhin (eds), Lenin: His Image in India, Delhi, Vikas, 1970, pp.

90, 92, 99, 105.

8. See Inprecor, 4/55, 4 August 1924, pp. 577–8.

9. Kobelev, Ho Chi Minh, p. 76.

10. David Petrie,

Communism in India 1924–1927, edited with an Introduction and Explanatory Notes

by Mahadevaprasad Saha, Calcutta, Editions Indian,

1972, p. 3.

11. ‘For the Tenth

Anniversary of the Imperialist War’, Inprecor, 4/43,

18 July 1924.

12. Kim San and Nym Wales, The Song of Ariran:

The Life Story of a Korean Rebel, New York, John Day, 1941, pp. 79–82,

quotation at p. 86.

13. Harsha Dutt,

‘Rabindranath Tagore and China’, Indian Literature, 55/3 (263) (2011), pp.

216–22, at p. 219.

14. Yin Zhiguang, Politics of Art: The Creation Society and the

Practice of Theoretical Struggle in Revolutionary China, Leiden, Brill, 2014,

esp. pp. 56–85; Wang-chi Wong, Politics and Literature in Shanghai: The Chinese

League of Left-wing Writers, 1930–1936, Manchester, Manchester University

Press, 1991, quotation at p. 14.

15. Sisir Kumar Das,

‘The Controversial Guest: Tagore in China’, China Report, 29/3 (1993), pp.

237–73, quotation at p. 253.

16. For Tagore and

Indian troops see Sugata Bose, His Majesty’s Opponent: Subhas Chandra Bose and

India’s Struggle Against Empire, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 2011,

p. 263.

17. Das, ‘The

Controversial Guest: Tagore in China’, quotation at p. 263.

18. Stephen N. Hay,

Asian Ideas of East and West: Tagore and his Critics in Japan, China, and

India, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1970, p. 181.

19. Ibid., pp.

237–8.

20. Yan Xu, The

Soldier Image and State-building in Modern China, 1924–1945, Lexington,

University Press of Kentucky, 2019, pp. 27–52, quotation at p. 41; Lincoln Li,

Student Nationalism in China, 1924–1949, Albany, NY, State University of New

York Press, 1994, p. 28.

21. Gerald W.

Berkley, ‘The Canton Peasant Movement Training Institute’, Modern China, 1/2

(1975), pp. 161–79.

22. Tan Malaka, From

Jail to Jail, vol. I, p. 41.

23. Rodney Koeneke,

Empires of the Mind: I. A. Richards and Basic English in China, 1929–1979,

Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 2004.

24. TNA, FO

371/11084, J. Crosby, ‘Notes on the national movement and on the political

situation in the Netherlands East Indies generally’, 30 April 1925.

25. Josephine Fowler,

‘From East to West and West to East: Ties of Solidarity in the Pan-Pacific

Revolutionary Trade Union Movement, 1923–1934’, International Labor and

Working-Class History, 66/1 (2004), pp. 99–117.

26. ‘Kuangtung’s unsettled state’, North China Herald, 5 July

1924.

27. The classic study

of these wars is Arthur Waldron, From War to Nationalism: China’s Turning

Point, 1924–1925, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

28. Ho Chi Minh

Museum, Hanoi, Nguyen Ai Quoc to Comintern, dated Canton, 12 November

1924.

29. James E.

Sheridan, Chinese Warlord: The Career of Feng Yü-Hsiang,

Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 1966, pp. 136–7, 146.

30. Marie-Claire

Bergère, Sun Yat-sen, Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 2000, pp. 339,

350, 395–8.

31. Arthur Waldron,

From War to Nationalism: China’s Turning Point, 1924–1925, Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press, 1995, pp. 223–6.

32. Prasenjit Duara,

‘The Discourse of Civilization and Pan-Asianism’, Journal of World History,

12/1 (2001), pp. 99–130.

33. Leonard Shihlien Hsü, Sun Yat-Sen: His

Political and Social Ideals, Los Angeles, University of Southern California

Press, 1933, p. 225.

34. Bergère, Sun

Yat-sen, pp. 369–70.

35. Torsten Weber,

Embracing ‘Asia’ in China and Japan: Asianism Discourse and the Contest for

Hegemony, 1912–1933, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, quotation at p.

206. See also Craig A. Smith, ‘Chinese Asianism in the Early Republic:

Guomindang Intellectuals and the Brief Internationalist Turn’, Modern Asian

Studies, 53/2 (2019), pp. 582–605.

36. Shuntian Shibao, 23 November

1924, quoted in Leslie H. Dingyan Chen, Chen Jiongming and the Federalist Movement: Regional Leadership

and Nation Building in Early Republican China, Ann Arbor, University of

Michigan Press, 1999, pp. 227–8, quotation at p. 245. Chen also cites the Hong

Kong Telegraph, 17 October 1924; I quote its reportage more fully here.

37. Aleksandr

Ivanovich Cherepanov, As Military Adviser in China, Moscow, Progress, 1982, p.

83; C. Martin Wilbur and Julie Lien-ying How (eds), Missionaries of Revolution:

Soviet Advisers and Nationalist China, 1920–1927, Cambridge, MA, Harvard

University Press, 1989, pp. 144–5.

38. Cherepanov, As

Military Adviser in China, p. 211.

39. James R. Shirley,

‘Control of the Kuomintang after Sun Yat-Sen’s Death’, The Journal of Asian

Studies, 25/1 (1965), pp. 69–82.

40. Suggested by

David Strand, An Unfinished Republic: Leading by Word and Deed in Modern China,

Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011, pp. 283–4.

41. Henrietta

Harrison, The Making of the Republican Citizen: Political Ceremonies and

Symbols in China 1911–1929, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 2000, pp. 133–46; Bergère,

Sun Yat-sen, pp. 395–407; Lian Xi, ‘Western Protestant Missions and Modern

Chinese Nationalist Dreams’, East Asian History, 32/33 (2006/7), pp. 199–216,

at p. 211.

42. Tan Malaka, From

Jail to Jail, pp. 100–103.

43. TNA, FO

371/11084, J. Crosby, ‘Notes on the national movement and on the political

situation in the Netherlands East Indies generally’, 30 April 1925.

44. C. F. Yong and R.

B. McKenna, Kuomintang Movement in British Malaya, 1912–1949, Singapore, NUS

Press, 1990, pp. 40–41.

For updates click homepage here