By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

British Policymaking at the End of

Empire and the Creation of Israel p.2

As seen in the sections of part one the Balfour

Declaration of 1917 became the first in a chain of events committing the

British government to a Jewish national home in Palestine.

While this subject

has been researched many times today it is generally accepted that British

politicians sought the means during wartime to limit long-term German threats

to the Empire. This was because the acquisition by Germany, through her control

of Turkey, of political and military control in Palestine and

"Mesopotamia" would imperil the communication through the Suez Canal,

and would directly threaten the security of Egypt and India.1 Although the

Sykes-Picot Agreement had concluded with an international Holy Land, neither party was satisfied. If the War Office wanted

to secure communication between Great Britain and the East, they would first

need to block residual French claims to Palestine.2 And possible of greatest

importance was the fact that the British Petroleum pipeline moved through

Palestine evident in their anxiety to ensure that the oil from Iraq was able to

flow freely to Haifa.3 Thus, Prime Minister David Lloyd, George intended to use

British forces advancing on Gaza to present the

French with a fait accompli, the British occupation of Palestine would

constitute a strong claim to ownership.4

It was not until the

first British invasion of Palestine was in motion, however, that Sykes

contacted the two men who would figure most prominently in British Zionist

diplomacy. In January 1917 he met with Secretary-General of the World Zionist Organisation Nahum Sokolow, and President of the British

Zionist Organisation Chaim Weizmann and the two

leaders made it clear to Sykes that they favored British rule in Palestine. The

following month Sykes introduced Sokolow to Picot, and the amicable meeting

resulted in the opening of a Zionist mission in Paris. Thus by the spring of

1917, the Zionist agenda was reassuringly recognized by the Entente. This,

combined with an underlying anti-Semitic belief in the power and pro-German

tendencies of "world Jewry", led to the final British agreement to

the Balfour Declaration.5

As we have seen in the previous links section the importance

of the Balfour Declaration foremost came from the fact that it was endorsed by

all major Allied powers. And whereby in 1917, there was not yet a League of

Nations or a United Nations, thus with the consensus of the Allies, there was

the nucleus of what at the time could be considered a modern international

order.

Balfour himself,

defending what came to be known as the Balfour declaration to the house of

Lords, described it as an exciting “experiment and adventure,” an exercise in

imperial imagination and territorial expansion.21 In July 1922, the Balfour

declaration’s commitment to mass european Jewish

settlement in Palestine was ratified by the League of nations document that

incorporated the wording of the declaration into the legal instrument that gave

Britain “mandatory” authority over Palestine. a few months later, the League

endorsed an additional British memorandum separating Palestine, now defined as

the area between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean, from a newly created transjordan and exempting the latter from the strictures of

the Balfour promise. The text of the Palestine mandate maintained some older ottoman

practices of communally conscious political organization, making provisions

for individual communities to maintain schools and religious institutions such

as waqfs and guaranteeing government recognition of religious holidays.

The mandate of the

League of Nations in 1922 interpreted the declaration to mean that the

country’s nationality law should be “framed

so as to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take

up their permanent residence in Palestine.”

The text of the

Balfour declaration itself is only a paragraph long, part of a letter from

Great Britain’s Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour (1848-1930) to Lord Walter

Lionel Rothschild (1868-1937). It was the product of behind-the-scenes

wordsmithing and political maneuvering; finalized on 31 October 1917 and

publicly issued on 2 November 1917, reading:

His Majesty’s

Government views with favour the establishment in

Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use its best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it

being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the

civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or

the rights and political status of Jews in any other country.

The key to

understanding the Balfour Declaration’s power is its creators’ word choices.

The passage “a national home for the Jewish people”, coupled with the

protection of “civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in

Palestine” and “the rights and political status of Jews in any other country”

rank among the most powerful and simultaneously ambiguous phrases in diplomatic

history.

The Balfour

Declaration may or may not have implied a Jewish state, but by affirming the

right of any Jew to call Palestine home, it changed the status of the Jewish

people. There was one small spot on the globe in which Jews had a natural right

to take up abode, by virtue of their “historic

connection.”

During the initial

meetings that laid the groundwork for the Balfour Declaration Chief Rabbi and

Zionist stalwart Moses Gaster told the acting adviser on Arabian and Palestine

Affairs, Mark Sykes, that Palestine should be organized on the lines of the Ottoman millet system.

Thus the Declaration,

however much desired or detested by British officials, was not ultimately their

idea. Jewish leaders had long contemplated a return to Israel and

reestablishment of a Jewish state. They envisioned a state defined by political

dimensions, however, not simply one based on religious or philanthropic

concerns. This concept emerged in the late 19th century, first voiced by

thinkers like Leo Pinsker (1821-1891) in

Auto-Emancipation (1882) and Theodor Herzl

(1860-1904) in The Jewish State (1896).

Trade-offs

undoubtedly affected the calculations of the principal Allied powers in 1917.

Some clearly had to do with the preservation or extension of the empire. Yet

what is astonishing is that all of these powers somehow converged in opening

the door to Zionism. This included not just such traditional rivals as Britain,

France, and Italy, all of which had empires, but the United States, which

championed self-determination, and even the Vatican.

Already during the

initial Sykes-Picot discussions France and Russia were asked, or as British

under-secretary Sir Arthur Nicolson put it:

It was clear that

"we must […] consult our Allies, especially in view

of the fact that we are discussing the future of Palestine at Petrograd"

[Sykes and Georges-Picot were in the Russian capital to negotiate the terms

under which the Russian authorities were prepared to assent to the Sykes-Picot

agreement]. He, therefore, proposed that "we might ask Paris and Petrograd

whether they see any objection to the formula pointing out to both the

advantages […] by securing a sympathetic attitude on the part of the

Jews."

Following the

appointment of Sir Mark Sykes as one of the civil assistant secretaries for

political affairs to the War Cabinet, Sykes at the end of January 1917 started

to define the area in which the Jewish chartered company proposed by the

Zionists could be active. The northern limit would be from Acre in a straight

line to the Jordan, which meant that the Hauran and the greater part of Galilee

was excluded. While the southern border "could be arranged with the

British government", Sir Mark also excluded the "islands of

Jerusalem, Jaffa and a belt from Jerusalem to the sea along the Jaffa railway

[…] because the Russian pilgrims came along this route". However, the

Zionists were appalled.

Thus the next day,

the secretary-general of the World Zionist Congress Nahum Sokolow, met with the

French representative François Picot. In the course of their conversation,

Sokolow observed that the Zionists desired that Palestine should become a

British protectorate. Reluctant to grant Palestine to the British, Picot

initially refused to be drawn and only mentioned that this was a question for

the Entente to decide.

On 28 February 1917,

Mark Sykes wrote to Picot that the "question of finding a (suzerain?)

power or powers in this region is especially beset with difficulties. To

propose it to be either British or French is to my mind only asking for

trouble, " while the alternative of an international regime would

"inevitably drift into a condition of chaos and dissension".

Prime Minister Lloyd

George, however, was emphatic "on the importance,

if possible, of securing the addition of Palestine to the British area".

After his arrival in

Paris Mark Sykes thought it wise to try and temper expectations at home. He

wrote to Sir Maurice Hankey Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence that he hoped the Prime Minister understood that

"the French public think that Palestine is Syria, and do not realize how

small a part of the coast-line it occupies".6 The next day, Sykes also

informed Balfour that "the French are most hostile to the idea of the USA

being the patron of Palestine", and that "the great mass of Frenchmen

interested in Syria, mean Palestine when they say Syria". Sykes also

believed that when the French started "to recognize Jewish Nationalism and

all that it carries with it as a Palestinian political factor [this] will tend

to pave the way to Great Britain being the appointed Patron of

Palestine".7

A first indication

that the French started to change their mind was the outcome of a meeting that

took place on 9 April between Sokolow, Paul Cambon, his brother Jules

(secretary-general at the Quai d’Orsay), as well as Georges- Picot at the Quai

d’Orsay. Sir Mark reported to Balfour the same day that "Zionist

aspirations (had been) recognized as legitimate by the French".8 In a

separate telegram to Graham, Sykes noted that "at interview question of

future suzerain power in Palestine was avoided"9 Naturally, the moment was

"not ripe for such a proposal […] but provided things go well the

situation should be more favorable to British suzerainty with a recognized

Jewish voice in favor of it".10

Ambassador to France Sir Francis Bertie did not share Sykes’s optimism

at all. He explained to Sir Ronald Graham that:

In dealing with the

question of Syria and Palestine it must be remembered that the French

uninformed general Public imagine that France has special prescriptive rights

in Syria and Palestine. The influence of France is that of the Roman Catholic

Church exercised through French Priests, and schools conducted by then […]

Monsieur Ribot [French prime minister and minister of foreign affairs] is of

the French Protestant Faith which in the eyes of the French Catholics as a body

is abhorred next unto the Jewish Faith. Even if M. Ribot were convinced of the

justice of our pretensions in regard to Palestine, would he be willing to face

the certain combined opposition of the French Chauvinists, the French

uninformed General Public, and the Roman Catholic Priests and their Flocks? 11

Sykes admitted the difficulty

with the "Syrian party in Paris" in a letter to Sir Ronald Graham

acting permanent under-secretary of 15 April. He observed that "what is

important is that this gang will work without let or hindrance in Picot’s

absence […] The backing behind this is Political-Financial-Religious, a most

sinister combination."12

A May 1917 letter

from Jules Cambon to Nahum Sokolow, expressed the sympathetic views of the

French government towards "Jewish colonisation

in Palestine".

" [I]t

would be a deed of justice and of reparation to assist, by the protection of

the Allied Powers, in the renaissance of the Jewish nationality in that Land

from which the people of Israel were exiled so many centuries ago,"

stated the letter, which was seen as a precursor to the Balfour Declaration.

The Jewish project enters the Vatican

After once more

visiting Paris where he met Picot in April 1917, Sykes next traveled to Rome.

As soon as he had arrived in Rome, Sykes sought an interview with a Vatican

official who was of the same rank and influence as himself, someone not a

cardinal who had the Pope's ear. He found his man in (the future Pope)

Monsignor Eugenio Pacelli, the Vatican’s assistant under-secretary for foreign

affairs. Sir Mark had gained the impression that "the idea of British

patronage of the holy places was not distasteful to the Vatican policy. The

French I could see did not strike them as ideal in any way." Sykes had

also "prepared the way for Zionism by explaining what the purpose and

ideals of the Zionists were". Naturally, "one could not expect the

Vatican to be enthusiastic about this movement, but he was most interested and

expressed a wish to see Sokolow when he should come to Rome". Sykes, who

had to leave for Egypt, had therefore left a letter for Sokolow in preparation

for his conversations with the Vatican.13 Sir Mark explained that he had been:

Careful to impress

that the main object of Zionism was to evolve a self-supporting Jewish

community which should raise, not only the racial self-respect of the Jewish

people but should also be proof to the non-Jewish peoples of the world of the

capacity of Jews to produce a virtuous and simple agrarian population, and that

by achieving these two results, to strike at the roots of those material

difficulties which have been productive of so much unhappiness in the past.

He had further

"pointed out that Zionist aims in no way clashed with Christian desiderata

in general and Catholic desiderata in particular", and strongly advised

Sokolow "if you see fit (to) have an audience with His Holiness".14

Sokolow was granted an audience on 6 May, which went very satisfactorily. The

Pope declared that he sympathized with "Jewish efforts of establishing

national home in Palestine", and that he saw "no obstacle whatever

from the point of view of his religious interests". He also spoke "most

sympathetically of Great Britain’s intentions". According to Sokolov the

length of his audience and the "tenor of conversation" revealed a

"most favourable attitude".15

A few days later,

Sokolow had an interview with Italian prime minister Paolo Boselli, who

indicated that Italy would not actively support a Zionist initiative in

Palestine but also would not oppose it.16 At the end of the month, Sokolow

returned to Paris and continued his conversations with the French authorities.

He was received by Ribot and by Jules Cambon. On 4 June Cambon wrote to him

that:

You consider that

when circumstances permit and the independence of the holy places is secured,

it would be an act of justice and reparation to assist with the renaissance,

through the protection of the Allied Powers, of the Jewish nationality on that

territory from which the Jewish people have been chased many centuries ago. The

French government, who have entered the present war to defend a people unjustly

attacked, and pursue the fight to ensure the triumph of right over might,

cannot feel but sympathy for your cause the triumph of which is tied to that of

the Allies.17

Sykes; almost three million Jews

Sykes in a note minuted to Sir James Eric Drummond private secretary to A.J. Balfour stated

that: "Having known Palestine since 1886, I am of [the] opinion that if the population is now

700,000, [and] granted security, roads, and a modest railway accommodation, it

is capable of being doubled in seven years . . . and with energy and

expenditure it would be quadrupled and quintupled within 40 years.”( Sykes,

note, not dated, minute Drummond, 30 October 1917, Foreign Office

371/3083/207407.) Meaning Sykes believed that there was a place for that many

Jewish immigrants (another almost three million) people could be added...

But contrary to Sykes

calculations, only 400,000 Jews would enter Palestine during the British

mandate period which as we shall see ended with the further explained White

Paper of 1939.

President Wilson "extremely favourable"

In a War Cabinet

meeting in September 1917, British ministers decided that "the views of

President Wilson should be obtained before any declaration was made".

Indeed, according to the cabinet's minutes on October 4, the ministers recalled

Arthur Balfour confirming that Wilson was "extremely

favourable to the movement".

While Sokolow may

have seemed like a diplomat, even to professional diplomats, he thought like a

publicist, eager to get the story out. He took every assurance he received and

made it public. Sokolow saw no point indiscretion for discretion’s sake.

President Wilson explicitly

asked that his prior approval of the Balfour Declaration not be made public,

and it wasn’t. But the Zionists publicized every other assurance. This had the

dual purpose of spurring competition among the Allies and raising the morale of

rank-and-file Zionists. But above all, an open assurance, communicated to a

vast public, could only be retracted at a cost.

One can also argue

that Woodrow Wilson applied the concept of self-determination differentially,

passively endorsing British unilateral arbitration over the appropriateness of

self-determination to Palestine. Wilson’s own dubious credentials as an anti-colonialist

were undermined by his own practices and willingness to employ imperial

prerogatives in the case of the settlements emanating from the Paris Peace

Conference.

Plus in the end had

Sokolow not secured the assent of other powers in 1917 for the hoped-for

British declaration, it would not have come about. And had he not returned to

regain their approval in 1918, it would not have become binding international

law. It is always crucial to “work” the great capital, London in 1917,

Washington today. But diversified diplomacy also aggregates the power that

resides in other centers around the globe. Such aggregation gave Zionism the

Balfour Declaration, the UN partition plan, and Security Council resolution

242. Absent it, Israel or its actions may yet be robbed of their international

legitimacy, especially if the “unshakable bond” with its great friend begins to

unravel.

Indeed, had the

Balfour Declaration been issued as a secret letter to Zionist leaders without

having been cleared by the Allies (that is, as the British promises to

Hussein), it would have never entered the preamble of the mandate, and Britain

probably would have disavowed it in the 1920s. But under the circumstances, it

was 'well-nigh

impossible for any government to extricate itself without a substantial

sacrifice of consistency and self-respect, if not of honor'.

The British would no

doubt have had far fewer qualms about violating a secret pledge made only to

the Jews. A public pledge that had been cleared and then seconded by the Allies

was another matter.

From Passfield's to the

White Paper of 1939

During a parliamentary

debate about Palestine on 17 November 1930 The British Prime Minister Lloyd

George started off with: We propose this afternoon to discuss the affairs of

one of the most famous countries in the world and the association with that

country of a gifted race which has made the story of that land immortal. It is

a very difficult problem to discuss because you have here two races involved,

with both of whom we have the most friendly relations, and what we want is that

justice should be done to the one without any injustice being inflicted upon

the other.

The same

parliamentary discussion also contained the testimony of Herbert Samuel,

Former High Commissioner of Palestine, 1930 who stated:

If there were any question

that the 600,000 Arabs should he ousted from their homes in order to make room

for a Jewish national home; if there were any question that they should be kept

in political subordination to any other people: if there were any question that

their Holy Places should be taken from them and transferred to other hands or

other influences, then a policy would have been adopted which would have been

utterly wrong. It would have been resented and resisted, rightly, by the Arab

people. But it has never been contemplated.

What undermined the

Palestinian Arab leadership the most, and in turn, the Palestinian movement for

self-determination was the infamous rivalry between the Husseini and Nashashibi

family history of occupying major political posts in Palestine since the Ottoman

era. In 1921, when the positions of Grand Mufti and the head of the Supreme

Muslim Council in 1922 were given to Amin Husseini by Samuel, the Nashashibis did not react negatively. This drew an even

greater wedge between the two families and in turn, this conflict dominated the

political life of Arab Palestine ever since.18

The debate shortly

thereafter was followed by the implication of the so-called Passfield

White Paper issued October 20, 1930, by colonial secretary Sidney Webb Passfield. The white paper limited official Jewish

immigration.

The Colonial

Secretary had warned Weizmann beforehand and Passfield

believed that Weizmann “took it very well indeed”. (The British National

Archives, Prime Minister’s Documents,1/102, 3 October 1930, Passfield

to Ramsay MacDonald.)

As has been pointed

out elsewhere the Jews in 1933 made it clear that they had no desire to place

any obstacle in the way of Arab national development because they had lived in

peace for centuries.19

The White Paper of

1939 however then introduced three measures: immigration quotas for Jews

arriving in Palestine, restrictions on settlement and land sales to Jews, and

constitutional measures that would lead to a single state under Arab majority

rule, with provisions to protect the rights of the Jewish minority.

Yet while the White

Paper advanced a British policy that came closer than any had before to meet

Arab demands, Palestinian Arab leaders rejected the document.

At the hearth of this

rejection was that Palestinian society, at the beginning of the twentieth

century, was confronted by the dramatic world-changing events with social,

economic and political consequences. These events shaped the political response

to the British Mandate rapidly metamorphosing from a society dominated by

pre-capitalist forms of social and economic relations into a society which was

attempting to deal with the forcible imposition of norms dictated by a world

power itself transitioning from colonialism into a new-imperialist power

implementing a neocolonialist practice. Palestinian society was in many

respects, unlike any other country which the British occupied and brought

within their imperial domain because it was in the process of becoming a part

of the wider world economy and had the capacity to continue to develop along

that path. Its economic, social and political progress was shaped by the

constraints imposed upon it by British imperialism’s primary concern to secure

its goal of preserving its own empire. This centered around its preoccupation

with the Near East and the Suez Canal. This focus was evident before the

adoption of the Balfour Declaration and was to re-surface during the 1930s as

the inter-imperialist rivalry reappeared. In the first instance, the Zionist

project was an adjunct to British imperialism’s main concerns, although this

was never the view held by the Zionist movement.

The Zionist majority

also rejected the White Paper because it signaled, at least symbolically, the

end of the ability of the Yishuv to rescue European Jews from Nazi Germany.

And thus the almost

three million Jews Sykes envisioned could be taken in would perish, leaving

only a few hundred thousand to be collected from the ashes. The Jewish

population of independent Israel reached the two-million mark only in 1962.

The plan to exterminate all Jews in British Palestine

Implicated as a

leader of the 1920 Nebi Musa riots Amin al-Husseini in order to inflame Muslim

opinion during the 1920’s circulated doctored photographs of a Jewish flag with

the Star of David flying over the Dome of the Rock. The British one could argue

helped politicize the issue by the decision to appoint Hajj Amin al-Husseini as

the grand mufti of Jerusalem.

In 1942 then Amin

al-Husseini visited Hitler to hatch a plan to exterminate half a million Jews

in what is now Israel which al-Husseini told Hitler would give the latter a

favorite status in the Arab world. And a day after the

Allied declaration regarding the murder of Europe's Jews on 17 Dec. 1942,

Grand Mufti al-Husseini gave a speech in which he argued that Arabs, and indeed

all Muslims, should support the Nazi cause. The Koran, he continued, was full

of stories of Jewish lack of character, Jewish lies, and deceptions. Just as they

had been full of hatred against Muslims in the days of the Prophet, so they

were in modern times. AI-Husseini then misconstrued Chaim Weizmann as having

said that World War II was a "Jewish war." (Amin

al-Husseini, "Nr. 55: Rede zur Eroffnung des

Islamischen Zentral- Instituts in Berlin, 18.12.1942 see also here.)

The first extensive

research about plans to exterminate the Jewish population of British Palestine

was made public via a 2004 Doctoral dissertation Wegbereiter

der Shoah. Die Waffen-SS, der Kommandostab Reichsführer-SS und die

Judenvernichtung 1939–1945 (= Veröffentlichungen der Forschungsstelle

Ludwigsburg der Universität Stuttgart. 4) by the German historian Martin Cüppers.

Further research with

the help of Klaus-Michael Mallmann then led to the publication of Halbmond und Hakenkreuz. Das Dritte Reich, die

Araber und Palästina (Veröffentlichungen der Forschungsstelle Ludwigsburg der

Universität Stuttgart. 8). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft,

Darmstadt 2006 and was translated as Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the

Extermination of the Jews in Palestine, 2010. Others who researched this

subject was the German Arabist Wolfgang G. Schwanitz who together with Barry

Rubin wrote Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 2014.

Around the time of

the Mufti's 1942 visit in Berlin German and Western intelligence services

reported high levels of pro-Nazi sentiment throughout the Arab world, including

Palestine, where “the extra-ordinarily pro-German attitude of the Arabs” was

due “primarily to the fact that they ‘hope Hitler will come’ to drive out the

Jews….”20

When Al-Husseini met

with Heinrich Himmler and Adolf Eichmann they secured a promise that an advisor

from Eichmann’s Jewish Affairs department would travel with him to Jerusalem

after the conquest of Palestine in order to extend the “final solution” to that

country.21

Thus plans to extend

the Holocaust to Palestine with the help of el-Husseini

led collaborators were in existence in 1942. The idea was for the German Africa

Corps to move down towards Palestine where a special unit was assembled and

trained in Greece in the spring of 1942 by SD officer Walter Rauff, the

originator of the gassing van experiments in Poland and the Soviet Union.

They were to operate

behind the lines with the help of those in the region who were eager to join

the task force. After El Alamein, the Einsatzkommando

shifted its operations to Tunisia, where it implemented cruel anti-Jewish

policies for many months.

Over 2,500 Tunisian

Jews were to die in the camps set up by the Nazis and their collaborators.

The German staff

required for this in Palestine were waiting for their march orders.

Only the defeat of

the German army both by the British at El-Alamein and by the USSR in the late

summer and fall of 1942 saved the Jews of Palestine and Egypt from

extermination.22

The Mufti openly

informed his Arab audience that; “The world will never be at peace until the

Jewish race is exterminated… The Jews are the germs which have caused all the

trouble in the world.”23 The Jews “have been the enemy of the Arabs and of

Islam since its emergence.”24

The Mufti’s call for

murder and ethnic cleansing would not fall on deaf ears. After 1948, 850,000

Jews were violently driven from Arab lands, stripped of their property and

passports.25 By one estimate, the Jews

forced out of just three countries, Iraq, Egypt, and Morocco, were dispossessed

of land that was more than five times the size of modern Israel.26

After the Nazi's

where defeated the Mufti next argued that "as soon as the British forces

were withdrawn, the Arabs should with one accord fall on the Jews and destroy

them."27

The secretary-general

of the Arab League, Abdul Rahman Azzam, in October 1947, was quoted in an

Egyptian newspaper as predicting that the impending war over Palestine “will be

a war of extermination and momentous massacre.”28

Given this

background, it is hardly surprising that fear of another Holocaust was a major

motive driving Zionist forces to fight in 1947–1948.29

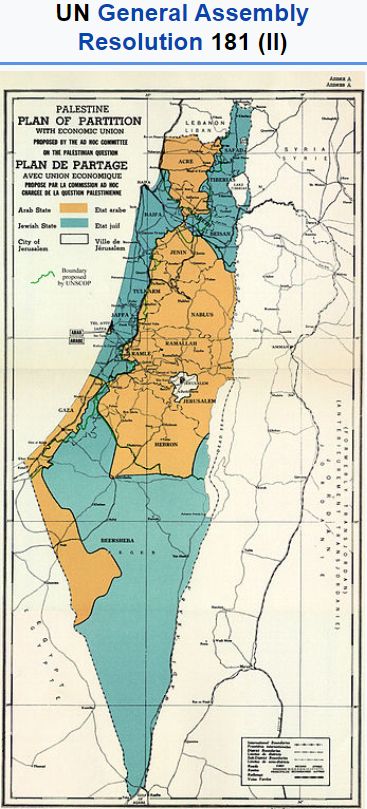

The United Nations ends the White Paper

When American troops

liberated Nazi concentration camps and discovered the surviving remnant, of

Holocaust survivors across Europe President Truman took notice. Following a

report from Earl G. Harrison into the conditions of the displaced person camps

in post-World War II Europe, Truman began to pressure the British Government to

open Palestine to 100,000 Jews.

The inability of the

United States and Britain to come to an agreement was one factor in Britain’s

decision to turn the problem over to the United Nations. But equally important

was the weak British economy and the loss of India, upon which British imperial

strategy had long been based; and without which, Britain had no imperial

strategic use for Palestine.

All along the British

government had viewed the future of Palestine as a strategic question to the

Empire as a whole. By granting Israel its independence while allowing

agreed-upon sections for the Palestinian Arabs the United Nations ruled

differently. The resolution recommended the creation of independent Arab and

Jewish States and a Special International Regime for

the city of Jerusalem.

The Partition Plan, a

four-part document attached to the resolution, provided for the termination of

the Mandate, the progressive withdrawal of British armed forces and the

delineation of boundaries between the two States and Jerusalem. Part I of the

Plan stipulated that the Mandate would be terminated as soon as possible and

the United Kingdom would withdraw no later than 1 August 1948. The new states

would come into existence two months after the withdrawal, but no later than 1

October 1948. The Plan sought to address the conflicting objectives and claims

of two competing movements, Palestinian nationalism and Jewish nationalism, or

Zionism.

Shortly after the UN

decision, the combined armies of the seven independent Arab states,

Trans-Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen invaded the

Jewish State.

According to Benny

Morris, The Jews of Palestine “were genuinely fearful of the outcome and the Haganah chiefs’ assessment on 12 May [1948] of a

‘fifty-fifty’ chance of victory or survival was sincere and typical.”30

The phrase “victory

or survival” is telling. Only victory would ensure survival for the Jews, given

the nature and intentions of their enemy. Despite this dire situation, there

was no Zionist plan for the systematic ethnic cleansing of Arabs.

Zionist forces moved

quickly to secure territory assigned to them by the UN plan. This was by the

Israelis dubbed the war of Independence and the nakba

(catastrophe) by Palestinians.

The Zionist forces

won the war of 1947–1949 at a great cost. About one percent of the Jewish

population was killed and two percent seriously wounded.31 For the United

States today, comparable casualties in a war would mean about nine-and-a-half

million Americans killed or maimed. A war that inflicted such casualties on the

United States would be cataclysmic, a war for national survival.

The final campaigns

of the war where operation Horev (22nd December 1948-8th January 1949), fought

against the Egyptian Army, in which Israel captured the north-western sector of

the Negev Desert, and Operation Uvda, 6th-10th March

1949, against the Arab Legion (the Jordanian Army), reinforced with some Iraqi

units, in which Israel captured the rest of the Negev Desert down to Eilat and

the Gulf of Aqaba. As a result, the Israelis won control of the main road to Jerusalem

through the Yehuda Mountains (“Hills of Judaea”) and successfully repulsed

repeated Arab attacks. Thus early 1949 the Israelis had managed to occupy all

of the Negev up to the former Egypt-Palestine frontier, except for the Gaza

Strip.

Since the division in

1948, there have been any number of further partitions in our sense: Korea,

Cyprus, Germany, Yugoslavia, and Sudan, to name just a few. A transnational

study of the partition of British India and the British construction called

Palestine, though, provides the clearest possible view of the origins of this

idea as a strategy of British imperial rule across different territories.

Israel today

As for the legacy

of Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini while

honored by the Fatah party and President Mahmoud Abbas the Palestinian group

that most clearly reflects the world-view of al-Husseini is Hamas, the name

taken in 1987. by the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hajj Amin

belonged to the Brotherhood and actively supported it throughout his life.32As

German political scientist Matthias Küntzel has

pointed out, Hamas is truly the ideological heir to Hajj Amin al-Husseini in

the Palestinian community.33The Hamas Covenant or Charter (1988) is replete

with the antisemitic themes emphasized by Hajj Amin: Palestine is a sacred

Islamic endowment (waqf) that belongs only to Muslims and every inch must be

liberated from the Zionists (articles 11, 14, 15); there is no solution to the

Palestinian problem except by jihad; peace talks and international conferences

are “a waste of time and a farce” (article 13); there is an international

Jewish conspiracy, comprising the Freemasons and the Rotary and Lions Clubs,

that controls the world media and finance. This group was the cause of both

world wars and the collapse of the Islamic Caliphate, controls the UN, and is

behind all wars wherever they occur (articles 17, 22, 28, 32); the Zionist plan

knows no limits and seeks to conquer from the Nile to the Euphrates and beyond

(article 32); the Zionist conspiracy is behind all types of trafficking in

drugs and alcohol and aims “to break societies, undermine values,…create moral

degeneration, and destroy Islam” (article 28). The Hamas Covenant cites the

hadith about killing the Jews hiding behind rocks and trees that al-Husseini

included in his 1937 appeal to the Muslim world (article 7). It also invokes

the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (article 32).33

Writer Mukhlis Barzaq, a member of Hamas, stated that the fate of the Jews

should be “complete killing, total extermination and eradicating perdition.”34

On May 2, 2014, a

children’s program on official Hamas television featured the host interviewing

a little girl who said she wished to be a police officer when she grows up, “so

that I can shoot Jews.” The host responded: “All the Jews? All of them?” She replied:

“Yes.” The host remarked: “Good.”35

In 2011 Mahmoud

Abbas, President of the State of Palestine, stated that the 1947 Arab

rejection of United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a mistake he hoped

to rectify.

To this one can ad

that Palestinian nationalism’s first enemy is Israel, but as suggested earlier, if Israel ceased to exist,

the question of an independent Palestinian state would not be settled. All of

the countries bordering such a state would have serious claims on its lands,

not to mention a profound distrust of Palestinian intentions. The end of Israel

thus would not guarantee a Palestinian state. One of the remarkable things

about Israel’s Operation Cast Lead in Gaza was that no Arab state moved quickly

to take aggressive steps on the Gazans’ behalf. Apart from ritual condemnation,

weeks into the offensive no Arab state had done anything significant. This was

not accidental: The Arab states do not view the creation of a Palestinian state

as being in their interests. They do view the destruction of Israel as being in

their interests, but since they do not expect that to come about anytime soon,

it is in their interest to reach some sort of understanding with the Israelis

while keeping the Palestinians contained.

The emergence of a

Palestinian state in the context of an Israeli state also is not something the

Arab regimes see as in their interest, and this is not a new phenomenon. They

have never simply acknowledged Palestinian rights beyond the destruction of Israel.

In theory, they have backed the Palestinian cause, but in practice they have

ranged from indifferent to hostile toward it. Indeed, the major power that is

now attempting to act on behalf of the Palestinians is Iran, a non-Arab state

whose involvement is regarded by the Arab regimes as one more reason to

distrust the Palestinians.

Therefore, when we

say that Palestinian nationalism was born in battle, we do not mean simply that

it was born in the conflict with Israel: Palestinian nationalism also was

formed in conflict with the Arab world, which has both sustained the

Palestinians and abandoned them. Even when the Arab states have gone to war

with Israel, as in 1973, they have fought for their own national interests, and

for the destruction of Israel, but not for the creation of a Palestinian state.

And when the Palestinians were in battle against the Israelis, the Arab

regimes’ responses ranged from indifferent to hostile.

The Palestinians are

trapped in regional geopolitics. They also are trapped in their own particular

geography. First, and most obviously, their territory is divided into two

widely separated states: the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Second, these two

places are very different from each other. Gaza is a nightmare into which

Palestinians fleeing Israel were forced by the Egyptians. It is a social and

economic trap. The West Bank is less unbearable, but regardless of what happens

to Jewish settlements, it is trapped between two enemies, Israel and Jordan.

Economically, it can exist only in dependency on its more dynamic neighboring

economy, which means Israel.

Gaza has the military

advantage of being dense and urbanized. It can be defended. But it is an

economic catastrophe, and given its demographics, the only way out of its

condition is to export workers to Israel. To a lesser extent, the same is true

for the West Bank. And the Palestinians have been exporting workers for

generations. They have immigrated to countries in the region and around the

world. Any peace agreement with Israel would increase the exportation of labor

locally, with Palestinian labor moving into the Israeli market. Therefore, the

paradox is that while the current situation allows a degree of autonomy amid

social, economic and military catastrophe, a settlement would dramatically

undermine Palestinian autonomy by creating Palestinian dependence on Israel.

The only solution for

the Palestinians to this conundrum is the destruction of Israel. But they lack

the ability to destroy Israel. The destruction of Israel represents a

far-fetched scenario, but were it to happen, it would necessitate that other

nations hostile to Israel, both bordering the Jewish state and elsewhere in the

region, play a major role. And if they did play this role, there is nothing in

their history, ideology or position that indicates they would find the creation

of a Palestinian state in their interests. Each would have very different ideas

of what to do in the event of Israel’s destruction.

1. See also James

Renton, “Flawed Foundations: The Balfour Declaration and the Palestine

Mandate”. In Britain, Palestine and Empire: The Mandate Years, ed. Rory Miller,

15-37 (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2010), p.18.

2. The National

Archive, Cabinet Documents, CAB 21/77, undated, Committee of the Imperial War

Cabinet on Territorial Desiderata in the Terms of Peace, 1917.

3. See also Martin

Gibson, Britain's Quest For Oil: The First World War and the Peace Conferences,

2017.

4. Mayir Vereté “The Balfour Declaration and its Makers”. Journal

Middle Eastern Studies Volume 6, 1970: 48-76.

5. See also Mark

Levene, “The Balfour Declaration: A Case of Mistaken Identity”, The English

Historical Review 107 (422) 1992: 54-77, 58.

6. Sykes to Hankey, 7

April 1917, Cab 21/96.

7. Tel. Sykes to

Balfour, no. 1, 8 April 1917, Sykes

Papers, box 1.)

8. Sykes to Balfour,

no. 2, 9 April 1917, ibid.

9. Sykes to Graham,

no. 3, in tel. Bertie to Balfour, no. 334, 9 April 1917, Foreign

Office (henceforth FO) 371/3045/73658.

10. Sykes to Balfour,

no. 2, 9 April 1917, Sykes Papers, box 1.

11. Bertie to Graham,

private and confidential, 12 April 1917, FO 371/3052/82982.

12. Sykes to Graham,

no. 2, 15 April 1917, ibid.

13. Sykes to Graham,

no. 3, 15 April 1917, FO 371/ 3052/82749.

14. Sykes to Sokolow,

14 April 1917, encl. in Sykes to Graham, no. 3, 15 April 1917, ibid.

15. Sokolow to

Weizmann, in tel. Rodd to Balfour, 7 May 1917, FO 371/3053/92646.

16. Jonathan Schneer,

The Balfour Declaration, 2011, pp. 217–18.

17. Cambon to

Sokolow, 4 June 1917, FO 371/3058/ 123458.

18. Taysir Nashif, “Palestinian Arab and Jewish Leadership in the

Mandate Period,” Journal of Palestine Studies 6:4 (Summer, 1977), 120.

19. Extract from

Daily News Bulletin, 10 January 1933, Nationa

Archives CO 733/235/5; see also Benjamin Braud, and Bernard Lewis,

Introduction, in Benjamin Braud, and Bernard Lewis (Edited by), Christians and

Jews in the Ottoman Empire, vol.1, 1982, p.1.

20. Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of

the Jews in Palestine, 2010, 133–134; cf. 132–139, 160, 163–164.

21. Mallmann and

Cüppers,129; also Barry Rubin and Wolfgang G. Schwanitz, Nazis, Islamists, and

the Making of the Modern Middle East, 2014,163.

22. Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, 154–166.

23. Jeffrey Herf,

Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World,184.

24. Herf, Nazi

Propaganda for the Arab World,185.

25. Martin Gilbert,

In Ishmael’s House: A History of Jews in Muslim Lands (New Haven and London:

Yale University Press, 2010), 235. See also: Maurice M. Roumani,

“The Silent Refugees: Jews from Arab Countries,” Mediterranean Quarterly 14

(2003): 41–77; Adi Schwartz, “A Tragedy Shrouded in Silence: The Destruction of

the Arab World’s Jewry,” Azure, 45 (Summer 2011), 47–79; Norman A. Stillman,

Jews of Arab Lands in Modern Times, 2003,141–180.

26. Gilbert, In

Ishmael’s House, 330–331.

27. Klaus Gensicke and Alexander Fraser Gunn, 2015 183, see also:

Rubin and Schwanitz, Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle

East, 192–200; and 1948: Benny Morris, A History of the First Arab-Israeli War,

2008 408–409.

28. David Barnett and

Efraim Karsh, “Azzam’s Genocidal Threat,” Middle East Quarterly, 18 (2011),

85–88.

29. Benny Morris,

1948, 397, 399.

30. Morris, 1948,

400–401; cf. Anita Shapira, Israel: A History (Waltham MA: Brandeis University

Press, 2012), 163.

31. Morris, 1948,

406.

32. Elpeleg, The Grand Mufti, 115, 120, 124–128; Herf, Nazi

Propaganda for the Arab World, 240–254; Küntzel,

Jihad and Jew Hatred, 36–37, 44–46, 48, 52, 58; Gensicke,

The Mufti of Jerusalem and the Nazis, 190.

33. Matthias Küntzel, “Das Erbe des

Mufti,” in Tribune: Zeitschrift zum Verständnis des

Judentums, 46, No. 184, December

2007),158.

34. “The Covenant of

the Islamic Resistance Movement—Hamas,” Middle East Media Research Institute,

MEMRI, Special Dispatch Series No. 1092, February 14, 2006,

http://www.memri.org/report/en/0/0/0/0/0/0/1609.htm. Azzam Tamimi argues that

the Covenant no longer reflects the thinking of most Hamas leaders. See: Azzam

Tamimi, Hamas: A History from Within, second ed. (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch

Press, 2011), 147–156. This claim should be rejected as false because Hamas has

had 26 years to revoke or revise the Covenant and has done neither. Statements

from Hamas leaders and official Hamas media outlets in Arabic continue to echo

the Covenant, especially its paranoid antisemitism (see below). Tamimi’s

assertion is based entirely upon interviews he conducted with major Hamas

leaders, who knew that he was writing a book in English for a Western audience.

It is clear from the evidence submitted by the U.S. government prosecutors in

the 2007 Holy Land Foundation trial that Hamas leaders practice deliberate

deception when addressing Western audiences, invoking Muhammad’s saying that

“war is deception” as their justification. See: Lorenzo Vidino,

The New Muslim Brotherhood in the West (New York: Columbia University Press,

2010), 177–186. Azzam Tamimi is at least an ardent supporter of Hamas and

probably also a member of Hamas. See: A. Pashut, “Dr.

Azzam Al-Tamimi: A Political-Ideological Brief,” Middle East Media Research

Institute, Inquiry and Analysis Series, MEMRI, Report No. 163, February 19,

2004, http://www.memri.org/report/en/print1066.htm. Therefore, Tamimi’s book

and the interviews on which it is based are manifestations of a strategy of

deliberate deception. They should not to be taken at face value. An additional

piece of evidence is the statement by Hamas leader Mahmoud al-Zahar that Hamas

“will not change a single word in its covenant,” in: Matthew Levitt, Hamas:

Politics, Charity, and Terrorism in the Service of Jihad (New Haven and London:

Yale University Press, 2006), 248.

35. Meir Litvak, “The Anti-Semitism of Hamas,”

Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture, 12:2–3 (2005),

http://www.pij.org/details.php?id=345.

36. Marcus and Zilberdik, “Hamas to kids: Shoot all the Jews,” Palestinian

Media Watch, May 5, 2014,

http://palwatch.org/main.aspx?fi=157&doc_id=11384.

For updates click homepage here