By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The secret mission of

the three interventions against Russia was to establish a signals intelligence support

group, which was meant not only to guarantee British access but also to serve

as a relay for intelligence gathered within Russia and the surrounding areas to

London, where it would serve as an informed and reliable basis for further

action. Without such signals intelligence presence, the War Office was blind.

Their planners were

primarily intelligence-operations specialists whose objectives were to preserve

and expand the Empire by reconstituting Russia "to withstand German

economic penetration after the war."

This is why, in the

beginning, there were so few troops sent to either of the two areas: there was

no need for them. Their purpose was to extend intelligence; that was a

technological matter, which required a small supporting military group.

When Spies invaded Russia p.2

To mold irregular warfare into a method which honored

the Imperial myth

In part one I referred to the intelligence

stage of what morphed into a military intervention then led by the War

Office. Because the initial Persia (Iran) plus North and South and Eastern

Russia interventions took place at such geographically and politically

different areas, each has been treated as though it were a separately

determined action or as though it was part of an overall Allied policy of

hostility toward Bolshevik Russia. The tendency in the literature about the

subject to date has been to dislocate these actions from their time, misplaces their

genesis (a plan which had begun to take shape in November 1917), and overlooks

their provenance within the imperial context of global geopolitics. Very

important was also signals intelligence access into specific geographic areas

of an otherwise inaccessible region for reasons which had only partially to do

with Russia. Hence early in the war, a provision had been made for a

"Government cable (owned by the British and Russian Governments) from

Peterhead to Alexandrovsk on the Murmansk

coast." The new cable would be the substitute for the previously customary

route which sent traffic with Russia via the Danish-controlled Great Northern

Company’s cables connecting the United Kingdom and France with the Scandinavian

countries and thence to Petrograd via Sweden and Finland. The Great Northern

Company’s staff in Sweden were subject to the control of the Swedish

Government, and, although no concrete case of "leakage" in Sweden was

ever established, there was reason to fear that the Germans might take advantage

of their friendly relations with Sweden to tap Allied messages passing through

that country en route to or from Russia.

As Heather Alison

Campbell explained in her 2014 Doctoral dissertation

that is currently being worked into a book, before his elevation to the

Foreign Office, Curzon initially flexed his muscles over the Mesopotamia

Administration Committee, of which he became chair in March 1917. By 1918, the

organization had developed into the Eastern Committee and included members from

the War, India, and Foreign Offices. Ostensibly, it was the Eastern Committee

that was the coordinating body for Britain’s overall strategy in places such as

Persia and Mesopotamia (in modern days roughly corresponds to most of Iraq,

Kuwait, parts of Northern Saudi Arabia, the eastern parts of Syria,

Southeastern Turkey, and regions along the Turkish–Syrian and the borders

Iran). Permanent members of the committee included General Smuts, Arthur

Balfour, Edwin Montagu and Sir Henry Wilson (CIGS) and frequent attendants

included General MacDonough (the Director of Military Intelligence).

Heather Campbell also

accurately points out that Russia was a very real nemesis to Britain in the

period prior to the First World War she also rejects the idea that the central

feature of Britain’s attitude towards Russia after 1917 was a hatred of Communism.

And while this has been constructed as an explanation for Britain’s

participation in the intervention it does not work to explain the whole of

British policy towards Russia after 1917, for as soon as one shifts focus to

the south of that country, one sees that the Malleson

mission to Meshed and the Dunsterforce initiative in

Baku, for example, were not conceived as part of an ‘anti-Bolshevik crusade’.

Instead, Malleson and Dunsterville

were First World War manifestations of a decades long British obsession with

the security of India’s borders. Which leads to another point: was Perfidious

Albion really so concerned with what was occurring some 1600 miles away from

its mainland that it would send money and troops into Russia and Central Asia

simply to counter an ideology it did not like?

The new class of

intelligence professional that developed early on during the First World War

was part of the rapidly growing and increasingly complex division of labor

developing throughout all Europeanised societies at

the turn of the last century. It was as much a part of this general societal

re-ordering as any other workgroup. Thus the influence of military

professionalism (as also was the case in Germany) had extended to the amorphous

field of systemized intelligence work.1

In this context, the

Directorates of Military and of Naval Intelligence emerged as super-agencies,

not only because of the natural tendency of bureaucracies to expand but for

many of the same reasons for which Lloyd George created and imposed his streamlined

War Cabinet: to regularise the conflicting

information which was crippling the management of the war.2 The re-organization

of the Directorate of Military Intelligence (D.M.I telegraphic address 'Dir-milint') brought together interests which had been scattered

throughout the government into one or two broad, topical groups holding

centralized geographic responsibilities.

On 23 December 1915

“a Military Intelligence Directorate, in addition to the Military Operations

Directorate was formed under the Chief of the Imperial General Staff” as part

of the General Staff re-organization of the same month.3 Initially supervised by

MajorGeneral C.E. Call well, the DM1 inherited eight

“sections” which were· primarily concerned with intelligence functions from the

Directorate of Military Operations (DMO). The directorship of General Caldwell,

the eminent military operations analyst, was interim, for on 3 January 1916,

Major-General G.M.W. Macdonogh was appointed DMI, a

position in which he remained until his appointment as Adjutant-General in

September 1918.

The acronyms DMI and

DMO were not obscure at all: “Intelligence” and “Operations” precisely

differentiate the distinct missions handled by those two bodies. The terms

remain in use. The groups drawn together under DM1 at the start of 1916

consisted of MI1 through MI10, each with a specific area of concern, each

staffed with a variety of officers drawn from every conceivable theatre and

Imperial army. Each was directed by a General Staff Officer most often of the

first rank, but occasionally of second, who in some circumstances reported

directly to the DMI. The DMI continued to report to the Chief of the Imperial

General Staff. Within some of the groups, there were tiers of increasingly

specialized intelligence groups, some of which changed their responsibilities

as the immediate importance of the data which they were following either

shifted or evaporated. Thus, within a single sub-group, MI1, there appeared

various subgroups. These covered not only the secretarial work of the entire

Directorate but also the policy regarding cables and wireless; martial law;

international law; municipal law and draft bills touching the General Staff;

and traffic in arms. Section (j) originally handled the Secret Service. The

consolidation of 1916 saw MI1 divided into four subsections: MI1

(a)-distribution and registration of intelligence; MI1 (b)-co-ordination of

secret intelligence, investigation of enemy ciphers and policy regarding

Wireless Telegraphy; MI1 (c)-Secret Service; and MI1 (d)-Summaries of

Intelligence.4 MI1 (c) was responsible for Special Duties' according to the

official record- this was the customarily used description, inherited from

military nomenclature, for espionage.5

In 1917 it was

determined that a Section (1) was required, to produce special monographs

required by the MI1 on historical, military, political and strategical matters.

MI1 (I), in early 1918 was transferred to MI2, becoming MI2 (e), " as its

work had come to deal entirely with the countries dealt with by that section

..." The MI1 section remained throughout the war primarily concerned with

intelligence outside the British Empire.6

The section known as

MI2 went through a similar dizzying array of responses to altered

circumstances, but by January 1917, MI2 was responsible for Russia, China,

Tibet, Japan and Siam, the Balkans, the Ottoman Empire, the Far East, the

United States, South America and Africa, while MI3 dealt with the war in Europe

except for the order of battle of the Russian Army, the resources of Russia,

and the order of battle and resources of Italy, a curious mixture of

traditional intelligence interests applied to the Allied nations.

MI4 throughout the

war dealt with the supply of maps and map distribution in the field.

MI5continued its focus on contra-espionage; MI6 focussed

on questions of military policy connected with the economic and financial

resources of the enemy, MI7 dealt with press censorship, publicity, and

propaganda; MI8 handled cable censorship; MI9, postal censorship, and MI10 had

responsibility for foreign military attaches and missions. Sections MI1-4 and

MI10 reported directly to the DMI, constituting powerful links; the others,

operating more traditionally within the norms of military support intelligence,

reported through the Deputy DMI.

Knowing all this, it

is simple enough to recognize that the shifts in

the formation and deformation of the various intelligence units directly

responded to the catalysts produced by wartime demand. Then, an extraordinary

event took place in the DMI in January 1918. After all the meticulous

dis-entangling of operations from intelligence, the two were-for the only

time-re-combined. The new group was designated Military Intelligence-Operations

and was composed of assets gathered from MI2 (c) and M02. Its director was

Colonel Richard Alexander Steel.

MIO dealt "with

all matters concerning Russia, Rumania, Siberia, Central Asia, Caucasus,

Persia, and Afghanistan." When it was dissolved on 1 June 1918, its

operations work "was handed back to DMO. who formed a new section,

M05," which remained under Steel's control. The intelligence work was

given to Steel's deputy, Major F.H. Kisch, and became a new section, MI2 (d).

In November 1918; "the development of the Russian situation" caused

such an increase in the volume of work within MI2 (d) that a new section,

Military Intelligence Russia (MIR), "was created to deal with Russia, the

Caucasus, Central Asia, Persia, Far East and to perform liaison duties with the

General Staff at Army Headquarters in India." Major Kisch received a

temporary promotion to lieutenant colonel, (GSO 1). MIR remained in operation

at least until January 1920, and probably continued its work after that date.7

Its acknowledged

duties concerned the analysis of military information corning from all parts of

the former Russian Empire, correspondence with the General Staff, India,"

and. "secretarial duties for the Interdepartmental Russia

Committee." These were combined with strictly political duties:

"information in regard to the political and military situation in European

Russia and Western Siberia, and the political situation in Eastern

Siberia," which covered the Syren/Elope operations. MIR (b) section,

monitoring the South Russia/North Persia Dunsterforce,

was devoted to "the political and military situation in Central Asia,

Persia, Afghanistan, the North Caucasus, and information emanating from

India" but "intelligence regarding the zone of operations of Turkish

troops" 8 was excluded specifically.

MIO's concerns during

the brief period of its existence were the planning and implementation of the

intelligence-operations phase of the interventions. In its position as an

intelligence-planning organization, MIO was the initiator of strategic

intelligence plans and their operational vehicles which moved intervention

policy, were endorsed by the War. Office, and were authorized by the Cabinet.

Colonel Steel, whose previous intelligence experience was distinctly modern in

its perceptions of the new uses of intelligence, exercised his particular

influence over Russian affairs as interpreted by the Imperial war government

and operations section; he recommended and orchestrated the policy underlying

all three of the seemingly unconnected interventions.

The similarities of

the interventions in terms of operations, objectives, and personnel were not

coincidental. The geographic sites and their attendant political, economic and

military situations had been monitored by Steel from his position in DMI for the

previous year and a half, and before that had been under continual appraisal by

MI1 (c). If "the erroneous estimate of allied observers hinged in large

part on ignorance of conditions inside Russia" 9 then it must be believed

that the interventions, as planned by MIO, were the designated intelligence

attempt within the stated and accepted goals of all intelligence activity to

remedy that ignorance. After all, even in 1917 intelligence-operations sought

out "those activities that involve the creation of intelligence."10

In the absence of

explicit political strategy, MIO section, through its influence over the

civilian political advisory groups concerned with Russia, intended to devise

its own intelligence strategy to safeguard Imperial relations with Russia. For

six months at the most critical time of the war, MIO acted as a policymaker in

lieu of any other over-riding civilian policy, using as its inspiration only

those already understood Imperial philosophies which had sustained its members,

their class, and their society. Except as it impinged on this objective, MIO

was not concerned with satisfying demands for justice, freedom or safety for

anyone other than Imperial Britain. Neither was it concerned immediately with

the post-war philosophy of national self-determination.

Steel and his

colleagues were in the unusual position of being able to analyze systematically

the totality of information collected in the field, fit it into the known

military capabilities of the nations and armies involved, and produce plans

based on that information which also met political requirements. By the time he

assumed his position as director, first of MI2 and then of MIO, Steel was also

benefitted by changes affecting Army doctrine. The official mind of the Regular

Army had gradually come to believe-although perhaps not accept-that unlike the

other two branches of service (Operations or Training), the Intelligence branch

was innately uncontrollable. To unduly restrict the manner or the particular

pursuit of information was to restrict its purpose; to dictate interpretive

methodology was to destroy the advantages such a group offered its sponsors.

Consequently, the

practical arrangements between command and intelligence were infinitely more

pliable than those between command and operations. Intelligence operating

outside the direct chain of command often had no specific orders, often could

not function with them, and would become meaningless if rigid controls were

imposed.

Once this shift in recognition

took place, as it did during the formation of the MI1, MI2 and MIO sections

between 1916 and 1918, predictive intelligence work was free to act as an

effectively separate policy agency within an Imperial government which was

increasingly dependent on professional experts. The existence of these agencies

no longer depended on one on the interpretation of orders through the chain of

command; they were not reliant on command cooperation to gain access to

operations or training. Intelligence agencies were licensed, within the limits

of their judgment, to initiate policy.11

The activities of

Steel and his co-workers depended on their independent strategic assessment

that the Russian collapse threatened Imperial security.

If any further

justification were necessary, the acquisition of the cryptographers confirmed

the strategic value of the new style of intelligence work in relation to

Imperial survival. That coup gave Steel an unusual authority to speak about

Russian plans in general, where before he might only have spoken directly for

the Persian theatre of operations where he had been attached; by extension, he

gained authority over the analysis of Russian plans against the Empire

generally. The response again was logical—with the resources which were

available some kind of intelligence network would be placed in North Persia to

enable Britain to guard India against Bolshevik ambitions, and the action in

the south was the ideal method of ensuring that a watch would be kept,

information gathered, and action taken. If such an operation was encouraged at

the southern edge of Empire, how much more necessary was it in the north and

the east? At the center of Steel’s effort was the civilian need to extend

intelligence lines and to extend them to very particular points. Those

locations were determined by civilian, not military, requirements. In North

Russia it was a question of protecting the only secure telegraphic installation

available—in South Russia, it was a question of establishing an intelligence

nexus in the dead space between Cairo and Simla. Both had the advantage of

being espionage loci; both required some kind of Imperial base to receive

information from agents moving into and out of the contested areas.

The Military

Intelligence-Operations (MIO) section of the War Office was formally

constituted on 30 January 1918," owing to the collapse of Russia." It

was a combined section for Intelligence and Operations work...formed out of the

personnel of MI2 (c) and M02 under Colonel RA Steel...It dealt with all matters

concerning Russia, Rumania, Siberia, Central Asia, Caucasus, Persia, and

Afghanistan. The experiment of combining intelligence and operations work in

one section was not a complete success, and on 1st June 1918, MIO was

dissolved, the operations work being handed back to DMO who formed a new

section, M05 to deal with it, while the intelligence work [went] back to MI2

and became MI2 (d) under Major F.H. Kisch.12

It liaised with

general Mikhail Alekseyev, General Denikin and Koltchak

at Archangel and Vladivostok, and with Baratoff in

the Caucasus.13 When MIO was dissolved, Steel was transferred to head M05. By

1919, Steel’s responsibility was officially listed as the supervision of

operational questions relating to Siberia and the Far East, as well as

supervision of General Knox’s Mission and the Briggs Mission to the Ukraine and

the North Caucasus-the military interventions.14 Steel was the connexion between the two parts of what we have come to

know as the interventions, between their initial planning and intelligence

operations phase lasting from about December 1917 to June of 1918, through

their subsequent military implementation.

MIO and its members

were thus singularly responsible for furnishing all forms of intelligence to

provide "the information upon which the Cabinet and War Council had to

decide the military measures to be adopted." The "relevant situation

reports and military studies" had their origin in its office.15

Its subsection, MIO

(a), under Major Frederick Kisch, took advantage of both Bruce Lockhart and

Sidney Reilly.16 The network of information which ended up in MIO may have

overwhelmed its analysis role, but at least the problem was finally, formally,

united with the individuals who had been trying to solve it, within an

arrangement which was not subsequently repeated. No other intelligence section

during the war was granted similar direct operations authority at War

Office/DMI level, although within the nets woven by Mil (c), an agency

fundamentally less hospitable to straightforward military behavior, such

actions were conducted. Some even succeeded.

But in Russia, where

the battles were politically based, where the rhetoric and the military actions

were recognisable, where intelligence agreed with

political assessments that distributing large sums to swashbuckler Russians

would get no results, but that the distribution of large sums to leading

industrial and financial entrepreneurs might,17 an attempt to organize a

countervailing and controlled guerrilla strategy to ensure Imperial goals was

at odds with reality. The application of 'civilized' military intelligence as a

substitute for 'civilized' military action—and in a very real sense, the

abdication by the responsible intelligence service of the option to take

control of the politics of the situation, leaving that element to the recognised British and Imperial government crippled the

interventions’ objectives. It was this diminution of on-site control which

hamstrung MIO plans, and the limitation of control in the interests of

professionalization effectively nullified the advantages which guerrilla warfare

offered.

Unlike the other foci

of intelligence actions, and unlike its civilian counterparts, military

intelligence could not withdraw from the military structure and doctrine, even

when it was attempting to loosen its requirements. As part of its attempt to

prove that the concept of intelligence-operations had specific advantages,

particularly within restrictive military environments, MIO relied on two

factors external to the missions themselves. They had depended on a kind of

overall political disregard for the technical aspects of their strategy, and

they had depended on the co-operation and Imperial devotion of the Dominions.

The first, shielded MIO activities only until the areas on which they were

concentrating became politically active. The second turned out to be less

reliable than had been believed. At Dominion senior political levels, where

'the ties of culture and of commerce are more intangible than those of

political dominion’ depending "upon the corporate determination of the

whole body politic,"18 MIO had been fairly secure when it set out to get

political endorsement of its plans, and a supply of men from Canada by using

its links with Milner’s allies. It had not, however, fully reckoned on the

political activism within the Dominion.

One of the most

important reasons for the internal reliance on Dominion troops was not their

mere availability. Certainly, Dominion officers and other ranks were placed

under General Frederick Poole’s command within the North Russian Syren/Elope

parties, and at Baku, the proportions of Dominions to Imperials was fairly

high. The Vladivostok campaign, drawing some of its training staff from the

failed Dunsterforce group, even saw the Dominion

influence so increased as to have a Canadian general in command. In the case of

Vladivostok, which was an essentially regular campaign, MI retained its overall

authority to manage information, deciding when and with whom to share it.

Another factor which

encouraged Military Intelligence to recruit Dominion soldiers was the

conclusion by Vernon Kell of a series of alliances between various Dominion

security agencies and his agency. He had:

remained in charge of

a "chain of Imperial Special Intelligence" in the British Empire.

With the support of the Colonial Office, he had established "personal

liaison" with colonial administrations in August, 1915. "Special

Intelligence liaisons” with the dominions took longer to establish. The Union

of South Africa did not authorise its Provost Marshal

to cooperate with Kell until June 1917. But by the end of the war Kell reported

that all dominions were "eager to cooperate" with MIS in

counter-espionage and "the prevention of Bolshevik activities."19

Perhaps the interest

in a militant philosophy directly in opposition to Imperialism was

understandable; what was more startling was that the Empire did not necessarily

choose to inform its Dominions of those concerns. In one of the most glaring

examples of this neglect, it was the Americans who finally told the Canadians

of the impending British transfer of their "Intelligence and propaganda

bureaus to Souther [sic] Russia from Archangel..

"20 In a time when every scrap of information had value, when every

decision rested on dozens of differing and conflicting estimates of its

consequence, and when every consequence could result in unforeseeable

repercussions of the greatest severity, even such a small thing as where to

send the intelligence bureaux could not be published

lightly. After all, when it became known that the bureaus were moved, the only

possible conclusion to be drawn was that the operation in the north was

failing. Even as the military, by necessity, became more willing to allow intelligence

to function quasi-independently in parallel with civilian policy, Lloyd George

was conceiving alternative governmental methods to achieve his objectives by

tacitly encouraging the parallel development. One was the restructuring of the

ways in which information was handled, exemplified by Maurice Hankey’s role

within the re-organized five-member War Cabinet. Hankey’s system made it

possible for all manner of actions, information, reports, and suggestions to

actually be considered and acted upon by the Cabinet with fair speed. It

fostered the "short, business-like discussions between the four or five

Cabinet-Ministers or professional experts brought in for the discussion."21

Lloyd George’s new way of handling the Cabinet discussions had distinct

advantages.

It had also distinct

disadvantages. In bringing into the Cabinet "professional experts,"

the new system allowed those same experts great latitude in influencing Cabinet

policy. The second disadvantage to the Cabinet, although not necessarily to

Lloyd George, was that centralisation of information

led to control of information dissemination. Thus those who controlled

information had control.

Lloyd George, with

his political need to retain access to all information, was willing to create

parallel agencies reporting primarily to him. The nature of coalition

government made Lloyd George especially dependent on such affiliates. Such

personal authorization easily tolerated the autonomous objectives of shadowy

groups which more regular administrations would never have endured. The

Cabinet, in the same spirit of power consolidation, also streamlined its

internal committee system. The new, unified Eastern Committee absorbed the

various subcommittees which had once had authority, substituting strategic for

tactical planning. One of the first to be gobbled up was the old Russia

Committee, and even the Foreign Office was excluded when Curzon declared there

was "not likely to be any present need" for their permanent

representation.22 If Lloyd George could

establish separate information lines, then so could Curzon.

The Russia Committee

which had dealt "for the most part, with technical matters,"23 was

virtually the only part of the Russia Committee system Curzon retained.

Instead, Curzon’s committee consolidation allowed "what were really three

aspects of one problem"24 to be dealt with under direct War Cabinet

authority 25 and, under that authority, to smooth MIO’s direct access to

influence. Operational actions pursued under Eastern Committee aegis were

functionally withdrawn from the normal chain of command. The Cabinet acquired

its own military arm. That such designated units would also serve as MIO’s

operational group, and enactor of its own intelligence policy was a

little-remarked side effect.

The environment was

favorable for the emergence of intelligence as a tool co-equal with military

force, and its growing influence on civilian policy. For a very brief period,

and as a consequence of an intersection of Imperial philosophy and wartime necessity,

intelligence drove policy. The interventions simultaneously marked the

substitution of strategic for tactical intelligence-operations, and the birth

of a raison d’etre, frozen in time, which has been

available to intelligence agencies ever since.

According to

then-Colonel A.W.F. Knox, British Military Attache in Petrograd, in his secret

note on the Present Situation in Russia, "On the 24th January 1918, the

War Cabinet authorised the Secretary of State for

Foreign Affairs to approach the Allied governments with a view to Japanese

intervention" at Vladivostok. The chain of events which would lead to the

operational institution of the MI2 idea of cutting Russia into thirds—northwest

to southeast; from Archangel to Vladivostok; with the final third proceeding

northwards from Baku—was thus formally endorsed.26 No such authorization could

ever have originated at War Cabinet-level under the conditions prevailing

within the British Government of the day. By convention and bureaucratic

common sense, any such approach would have originated at senior General Staff

levels within the War Office. Formulation of plans of this kind was the

responsibility of the groups specifically charged with creating predictive

strategical responses to military events. It was for precisely this eventuality

that such groups had been established-not for elaborate political gestures, but

to provide the planning capabilities for the operational sections to use. For

the approach to have been authorized on 24 January 1918, the plan itself also

has been formulated in the days, weeks, or months before presentation, and must

have been devised as a consequence of events which made the creation of such an

extraordinary plan appear necessary and desirable.

MIO’s original

proposals to solve the Russian problem were quite different from those produced

later during the interventions’ aggressive military phase. Those original

recommendations depended for their implementation on the actions of military

intelligence officers and Missions already operating in Russia under a variety

of formal instructions. Within those instructions, though there was latitude

for tactical military intervention, there was no indication from the pattern of

activity discernible at that stage that the interventions would become a wholly

military operation. The amount of energy which MIO expended to keep the

operations within the boundaries it had defined for them is indicative of its

belief that to allow the interventions to become entirely military would be an

invitation to defeat of the plan itself. All parties concerned were aware that

such a military plan must rely on a massive troop commitment. When the

predictable setbacks occurred as a result of the "wholly inadequate troops

which the Government decided on,"27 they could not have been unexpected.

Implementation of a half-hearted military intervention when such action only

could have worked by being full-scale was tantamount to proclaiming the

experiment of integrating intelligence with operations a failure. The failure

occurring, subsequent overt uses of such intelligence-operations agencies to

create and achieve civilian policy were renounced by successor Imperial

intelligence groups themselves and by the political principals who inherited

them.

This plan as

originally formulated was replicated in its essentials at both the North and

South Russian interventions. It depended on the careful use of resources,

including local and imported troops, money and trade advantage, to persuade

rather than to coerce. All three

interventions were provided with economic advisors, whose business it was

to resist the German/Russian economic threat to Imperial interests while

furthering Imperial prospects. Furthermore, the plan depended on a curious but

not entirely novel form of suasion in which hostility was carefully directed

and turned in the direction of Imperial enemies, seemingly independently.

All three missions

initiated by MIO shared the same techniques which were later publicly trumpeted

operational objectives: regaining "well-disposed inhabitants" to the

Allies; securing a "strong demonstration against the enemy," which

was to be achieved in the north by concentrating a large number of Czech-Slavs.., into a

fighting formation; preventing the "White Sea and the adjoining ports on

the Russian coast being used for hostile submarine bases."28 These were

the final manifestation of MIO’s imperially based, hopeful, but operationally

flawed ideas on how to continue and enhance Imperial power within Russia.

As part of the

emphasis on secrecy which pervaded all three interventions, the despatch of intervention personnel was meant to be swift.

This turned out to be easier to accomplish at Archangel and Murmansk than it

was for the more remote bases. The first-despatched

group, authorized on 16 January 1918,29 only got to Baku on 4 August. The

mission to Vladivostok was not in position until 3 August. Because the Poole

Mission was already in place in North Russia it was marginally quicker in

adding the requisite training re-enforcements, which arrived at Murmansk on 24

May, They were followed by the Syren and Elope Missions, (now known as the

North Russia Expeditionary Force) which landed on 23 June.30

MIO offered its plan

to safeguard an over-extended military line by the creation of an

intelligence-based army—one flexible enough and loyal enough and responsive

enough to re-organize a deteriorating political system by substituting a

sturdier political creed. When, on 28 January, Colonel Steel gave Dunsterforce his "most interesting and instructive

lecture"31 and "unrolled a map of the Middle East," the

uncertainties of the Persian political situation which had brought them all to

the Tower was clearly the fault of the Russian withdrawal; given that, it took

no great imagination on the part of the volunteers to believe in the plan as it

was outlined. It had taken equally little imagination for the politicians to

endorse it. Steel had designed a clear solution to the problem, and had

obtained an almost perfect freedom to develop, direct, and compose first Dunsterforce, and subsequently Syren/Elope. If the training

mission succeeded, it did so on terms Steel and the military intelligence

system established; if it failed, there was every likelihood that no one would

have to notice. If the intelligence operation succeeded in protecting the

telegraph lines, the success would be noted; if they failed, things would be no

worse than before. The second most critical element of intelligence-operations

had been met. Imperial intelligence activity was, even in failure, deniable.

When Steel told Dunsterforce that he was "addressing the flower of the

British Army on the Western Front" and "the flower blushed

modestly," another, quite separate part of the Imperial structure was

being invoked one in which the military and military intelligence placed great

confidence. Steel was taking advantage of cultural rhetoric, resonant with

Imperial legend, in order to remind his men of their Imperial obligations and

responsibilities. When he told his audience that they had all "been

specially selected for this adventurous expedition," and that it was quite

possible that they "might be sacrificed on the altar of British prestige

in the Caucasus Mountains," Steel pushed that language and its

associations almost to its limits of believability. But not quite. The power

which that form of expression conveyed was still enough to overcome most

objections. Only then did Steel describe the situation they would be facing,

and we must believe that what Steel said to Dunsterforce

differed only in tone from what he had been saying to Curzon, Milner, and Lloyd

George. He said:

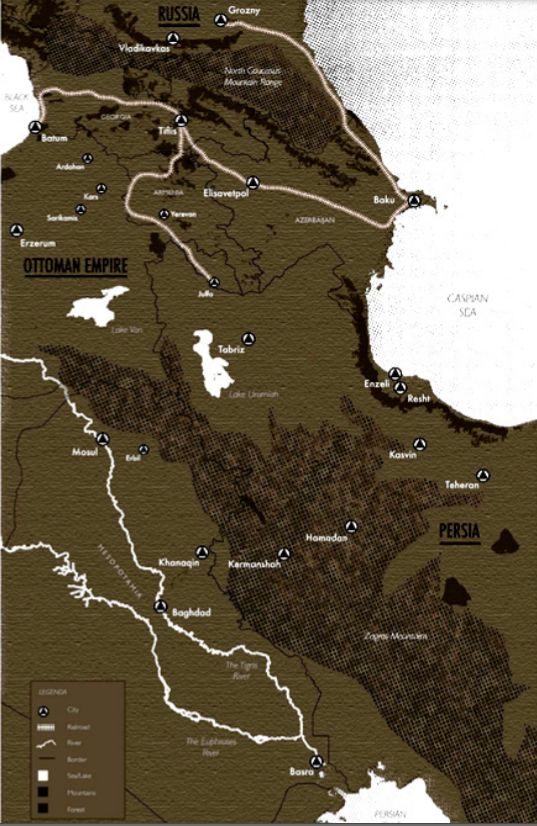

The capture of

Baghdad by the British in March 1917, had been offset by the Bolshevik

Revolution. The Russian front which had extended southward through the Caucasus

Mountains, across the southern end of the Caspian Sea, and down into Persia,

where it linked up with the British Mesopotamian Force at Khaniquin,

had now collapsed. The Russians were crowding back home, totally demoralized,

leaving a wide-open door to the eastward advance of the Turks and the Germans.

The age-old necessity of protecting India demanded some sort of a barrier to

replace the defecting Muscovites. But the British were expecting a German

offensive in France; Allenby was completely occupied in Palestine; the

Mesopotamian Army had no troops to spare. The situation was menacing. When things

were at their blackest, however, a War Office visionary had a brainstorm.

Somewhere in tire mountains of Kurdistan, Circassia, Armenia, and Georgia,

there were thousands of enthusiastic warriors who would snap at the chance of

squaring off their own private grudges against the Turk, if only they could be

entered on the British payroll and given good leadership. That was the

proposition—to penetrate into the Caucasus Mountains, raise an army, and use

that army, against the Turks.

Their destination.

Steel told them, would be Tiflis, and their commander was General L.C.

Dunsterville.32

This high-flown

justification of the expedition was meant to inspire not only the Imperials but,

by extension, the men whom they were to recruit. When Steel couched his

exhortation in the language of Imperialism-telling combat veterans they had

been "specially selected for this adventurous expedition" on which

they might "be sacrificed on the altar of British prestige in the Caucasus

Mountains," he has not laughed at neither his terms nor his implications

were regarded as anything but representative of what a brave Imperial soldier

might expect to hear, and in hearing, take heart. This was what the Imperial

government wished to convey. The military components of the Imperial

interventions were based absolutely on the legends which fueled the British

Empire itself: the legends of individual leadership, of honor of stalwart

defense of ideals which inspired others to follow. Unlike the horrors taking

place on the Western Front where warfare, far from being honorable, had decayed

into corruption, these legends still carried weight beyond politics in the

creation of the operations which Colonel Steel devised to meet the Russian

emergency. Every action in which Steel was involved was characterized by this

kind of attempt to mold the imprecise doctrines of irregular warfare into a

method which honored the Imperial myth within a modern framework-and which could

be taught, could be transferred; could be professionalized. Russia was the

testing ground; traditional imperial peripheral warfare there, offering the

hope that that front could escape a Western Front kind of hideous stalemate,

would decide on what basis the imperial military would proceed. It took the

hard and direct experience for the members of the various expeditions to

discover that the legends of Empire were a good deal less profound than they

once had been.

As explained the public assumption that

the military phase was the first and not the second involvement of Imperials in

North Russia was encouraged by the timing of events.

It was a risky game,

but the chaos in Russia led to some very uncharacteristic behavior on the part

of usually detached British governmental officials. Even such a calm soul as

Lord Robert Cecil, faced with the prospects of the withdrawal of all Russian

forces from the action, was led to exclaim that "we must be prepared in

the desperate position...to take risks."

In the latest 2019 book on related subjects,

Rupert Wieloch (p.22) writes that: "Two factors transformed the British

position from protecting supplies to active engagement in the civil war. The

first was the perceived imperilment of the Czech Legion' as it attempted to

extract 70,000 soldiers along the Trans-Siberian Railway The second was the

Bolshevik government's unwillingness to re-open the Eastern Front in the wake

of their treaty with Germany Austria-Hungary Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire,

known as the Central Powers."

While it true that

the Czech Legion as we shall see indeed played a role, as for the alleged claim

of a need to "protecting supplies " however it was in fact admitted

that the more valuable stores had already been removed to the interior of Russia.

The propaganda section of MI1, principally using friendly newspapermen, on the

other hand, gave detailed accounts of the amount and nature of the stores held

in supply dumps, and even senior ministers used their influence to spread the

story.

As is pointed out little understood is

that the original MIO mission in the north was, in fact, to establish a signals

intelligence support group, which was meant not only to guarantee Imperial

access but also to serve as a relay for intelligence gathered within Russia and

the surrounding areas to London, where it would serve as an informed and

reliable basis for further action. Without such signals intelligence presence,

the War Office was blind. When Henry Wilson declared that the reasons which

originally led to the despatch of Allied troops to

North Russia were "to maintain communications with the patriotic and

Anti-German elements in Russia," he meant it literally.

As the secret

post-war MI8 explanation had it, these access points to intelligence networks

were the "Special routes," established because it was "obviously

desirable to avoid, as far as possible, routes passing through the territory of

neutrals where the connecting lines were worked by a non-British staff and were

liable to be interfered with by a neutral Government, or tapped in the

interests of the enemy."

Early in the war, a

provision had been made for a "Government cable (owned by the British and

Russian Governments) from Peterhead to Alexandrovsk

on the Murmansk coast." The new cable would be the substitute for the

previously customary route which sent traffic with Russia via the

Danish-controlled Great Northern Company’s cables connecting the United Kingdom

and France with the Scandinavian countries and thence to Petrograd via Sweden

and Finland. The Great Northern Company’s staff in Sweden were subject to the

control of the Swedish Government, and, although no concrete case of

"leakage" in Sweden was ever established, there was reason to fear

that the Germans might take advantage of their friendly relations with Sweden

to tap Allied messages passing through that country en

route to or from Russia.

The Great Northern

route, which ran from Amoy, South China, through Siberia, Russia, and

Scandinavia was known to be strategically vulnerable as early as 1902, when

the French chose to construct a separate, French-controlled parallel in order

to avoid the irritants of both British interception of messages and political

and military interruption of traffic. The new

Alexandrovsk cable, however, was only able to

deal (and that sometimes with difficulty) with the large and important Russia

traffic of the Allied Governments. Ordinary traffic had... to be sent via

Sweden, although occasionally room was found on the Alexandrovsk

cable for certain especially important private messages, especially those

relating to shipping. Presumably, those private shipping messages contained

some traffic from HBC-controlled vessels, which were the primary

"privatized" ships with business in the area. That left the military

Russian wire traffic of the Allied governments.

MI8 first settled for

censorship and stopping suspicious messages, only imposing its "systematic

delay" policy covering all traffic dealing with telegrams 'to or through

Russia in November 1917. Information transfer in the theatre became ludicrously

slow, albeit considerably less prone to external enemy tampering. Although

telegrams for Russia (as well as for France and Italy) were largely exempt from

the systematic delay imposed on telegrams for other parts of the continent,

Imperial censors were instructed to give special scrutiny to messages to Russia

which had to transmit through Sweden, in view of the additional risk which this

involved. In November 1917, the systematic delay was also imposed on telegrams

to or through Russia, and the fact that such telegrams continued to pass

through Sweden was an additional reason for a decision which was based mainly

on the disruptions within Russia itself.

Different from the

above described intelligence led operations before they coalesced, the British

War office in cooperation with the Allied strategic objectives in Russia was to

re-establish an Eastern Front in cooperation with Russian groups that opposed

the Treaty of Brest Litovsk. On 18 May 1918 some 400 Russian Constituent

Assembly deputies met together and condemned the treaty, declaring

that the state of war with the Central Powers continued.

The German collapse

then made Trotsky’s task as leader of the Red Army, in political terms, a bit

easier. In spring and summer 1918, the Allied landings at Murmansk,

Vladivostok, and Archangel had been small-scale and, in theory at least,

friendly (see the end of the upcoming BritishAgentsRussia3.html). Only after

the Czechoslovak rebellion and Boris Savinkov’s uprising at Yaroslavl in July

had relations between the Entente powers and Moscow tipped over toward outright

hostility, and even then it stopped short of armed combat. The November 1918

armistice, ending the world war, tore off the mask of friendliness. Any

continued Allied military presence in Russia would be ipso facto hostile, which

the Bolsheviks could plausibly describe to peasant recruits as a foreign

invasion.

When Spies invaded

Russia p.1: British Spies from Persia to

North and South and Eastern Russia.

When Spies invaded

Russia p.3: The alleged protecting of

supplies propaganda.

When Spies invaded

Russia p.4. How North Russia evolved into

its military phase.

When Spies invaded

Russia p.5. What must develop into a civil

war.

When Spies invaded

Russia p.6: Spycraft

in Bolshevist Russia.

1. John Keegan, The

Mask of Command, (New York, Viking, 1987), p. 4.

2. India Office

Library and Records (hereafter IOLR), MIL/5/805, H.V. Cox to Steel, India

Office, 16 March 1918.

3. Public Record

Office, Kew (hereafter PRO), WO 32/10776, p.

4. Ibid.

5. War Office List,

1918, p. 102. The telephone number (Regent 3765) was listed, but in the

interests of secrecy, no room number was offered.

6. Ibid., pp. 8-9.

7. Ibid., p. 7.

8. War Office List,

1918, p. 98.

9. Robert B. Asprey,

War in the Shadows, vol. I, (Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1975), p. 337.

10. John I. Alger,

Definitions and Doctrine of the Military Art: Past and Present, (Avery

Publishing Group, Inc. Wayne, New Jersey, 1985), p.70.

11. Report of the

Ministry, Overseas Military Forces of Canada, 1918, p. 211.

12. PRO, WO 32/10776/102105,

'Historical Sketch of the Directorate of Military Intelligence During the

Great War, 1914-1919,’ 6 May 1921, p. 7.

13. War Office List,

1917.

14. Ibid.

15. Norman Bentwich and Michael Kisch, Brigadier Frederick Kisch:

Soldier and Zionist, (London, 1966), pps. 42-43.

16. PRO, FO

371/3350/#205769, 14 December 1918, p. 76. The government once suggested that

’Sir A. Steel Maitland might like to make use’ of Bruce Lockhart as Commercial

Secretary in South Russia.

17. PRO, FO 175.14

G.T. 3927, 5/3/18, A.W.F. Knox, 'Possibilities of Guerrilla Warfare in

Russia,’ to CIGS, p. 1.

18. Arthur D.

Steel-Maitland, The Empire and the Future, (London, 1916), p. vii.

19. Andrew, Her

Majesty’s Secret Service, p. 242. According to the author of the 1964 Canadian

Official War History, the Canadian mutiny was noted in a letter from its

commander, Colonel Sharman in April 1919, reporting that a section of the

Canadian artillery had temporarily refused to obey orders. NAC, Borden Papers

OC516-OC518 (2), MG 26, HI (a), vol. 103, pps.

55896-56582, reel C-4333, Nicholson 516; Col. Sharman to CGS 13 April 1919,

'Precis of Correspondence Relative to North Russian Force’ prepared for Sir

Robert Borden 17 May 1919; see also Julian Putkowski,

The Kinmel Park Camp Riots, 1919, (Clywd, Flintshire

Historical Society, 1989); and Julian Sykes, Shot at Dawn (Barnsley,

Wharncliffe Publishing, 1989).

20. National Archives

of Canada (hereafter NAC), RG9 III Vol. 357, SEF files, File A3 SEF #25; From

American Headquarters to Canadians, Vladivostok, December 5, 1918, 'Secret’.

21. John F. Naylor, A

Man and an Institution; Sir Maurice Hankey, the Cabinet Secretariat and the

Custody of Cabinet Secrecy , (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1984), p.

29.

22. PRO, CAB

24/45/65642 GT-3905, 13 March 1918.

23. PRO, CAB

27/23/WC/363, 11 March 1918, p. 137.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. PRO, FO 175.14,

'Note,’ Colonel AWF Knox, 'Present Situation in Russia,’ p. 247. NAC,

'Secret,' Colonel Richard A. Steel to Brigadier-General H.F. MacDonald, 23 July

1918.

27. Bentwich, pps. 42-43.

28. NAC, Borden

papers, #55520, MacDonald to Chief of the General Staff, 'Report,’ 17 July

1918 and NAC, RG9 III, Vol.358, A3 SEF #40, #63606, 'Secret,’ War Office to

Colonel Robertson, Vladivostok, repeated General Knox, 3 August 1918. The

structure of these actions was most conspicuously modified at Vladivostok, where

Allied numbers, (including both U.S. and Japanese), were more favourable to conventional warfare. However, through its

strong 'training’ component, that expedition maintained the element of

internal political manipulation which characterised

all three actions. In that way, although the U.S. contribution at Vladivostok,

which was sent in the last week of July 1918, was * 100,000 Russian rifles and

200 Vickers Guns and four and three quarter million rounds S.A.A. . . . 14,000

rifles and one million rounds. . . . Something under one thousand rifles . . .

and 75,000 suits of clothing for Czechs, ’and whilst Steel was able to report

that Great Britain was sending 'via Shanghai,’ 'one hundred and twelve million

rounds,’ the parallel organisations of intelligence

and operations were still folly engaged.

29. Military

Operations-Subsidiary Theatres, History of the Great War based on Official

Documents, Principal Events, 1914-1918, (London, H.M.S.O., 1922), p. 216.

30. Ibid.

31. W.W. Murray,

Canadians in Dunsterforce, Canadian Defence Quarterly, pp. 211-213.

32. Ibid.

For updates click

homepage here