During the course of

the Zhou Dynasty as compared with the case studies about Rome and early Europe,

it was shown how feudal states in China were more autonomous, had no

overlapping, cross-cutting authorities, and had strong territorial markers. And

that during the course of the Zhou Dynasty we see a shift from transbordersovereignty to absolute sovereignty with the

Warring States Period representing a

transitional phase to imperial China. From the age of Confucius onward, the

Chinese people in general and their political thinkers, in particular, began to

think about political matters in terms of the world.

Then when the Eastern

Han government gave up its attempts to restrict the rise of a dependent

tenantry, and in so doing abandoned direct administration of the countryside in part two we thus have seen how steppe chieftains

were given economic subsidies in return for longterm

military service to help protect the Chinese boundaries from other steppe

nations.

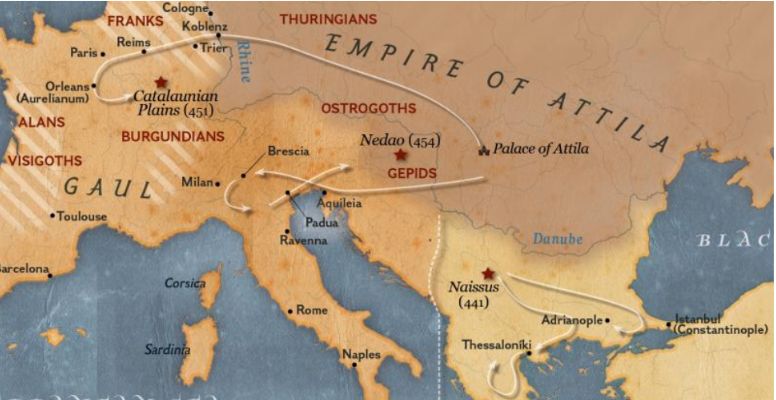

In the west

threatening the Roman empire, on the other hand, we will next see how the Huns

quickly expanded their territory with lightning-fast cavalry and accurate

archers, inspiring fear wherever they went.

In addition to their military might, the Huns were skilled at forging

alliances with local tribal leaders by exchanging goods for loyalty.

The Chinese Empire

recognized that war was an expensive prospect, and it was, therefore, better to

avoid large-scale conflict. Thus, to maintain peace on the frontiers, the later

Han regime paid massive subsidies to foreign nations to buy their workforce for

military service or to deter attacks. By the first century AD, the Chinese were

paying 101 million cash per year to the Southern Xiongnu

on the Han frontiers and 270 million to the Xianbei

on the Mongolian Steppe. Similar payments were made to the border-based Wuhuan nation and the Western Qiang on the southern borders

of China (Tibet-Burma).1 Amounts worth 740 million cash were equivalent to

about 148 million sesterces in Roman currency. This sum would have paid the

salaries of a large standing army, the equivalent of thirteen legions, except

that the Han considered it safer and more economical to purchase peace.

The early Chinese and

Roman Empires each faced different military, political, and financial

challenges. Both regimes had to raise substantial revenues to finance state

administration and create a military infrastructure that could prevent internal

unrest and deter foreign invasion. The Romans met these demands by spending

large sums on a vast professional army while the Chinese maintained a smaller

military structure and made tribute payments to external powers to ensure peace

and stability on their frontiers. Silk produced in Chinese workshops had a unique international value, and this gave the

Han a valuable renewable resource, other than precious metal, to pay border

troops and bribe foreign regimes.

The Chinese

established a large and expensive bureaucracy that could manage the high levels

of tax revenue extracted from its subjects. By contrast the early Roman Empire

generated much of its required income from mining precious metal bullion and

taxing the international commerce that developed between its territories and

the eastern world. Commercial taxes financed the Roman regime, but the bullion

that their merchants spent at trade centers in Babylonia, Arabia, and India was

a finite resource. Trade imbalances ensured that the Roman Empire could not

sustain its original prosperity or adapt to the challenges of late

antiquity.

Crucially, the Roman

military failed to master steppe warfare, and consequently, the appearance in

Europe of a steppe nation from East Asia was to cause the collapse of their

empire.

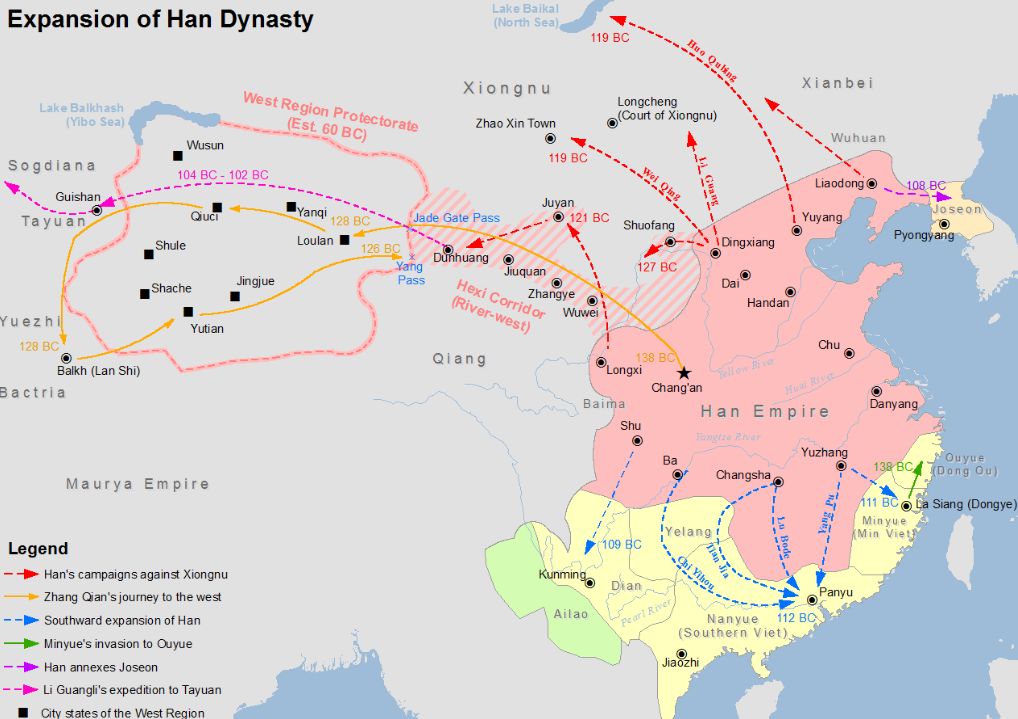

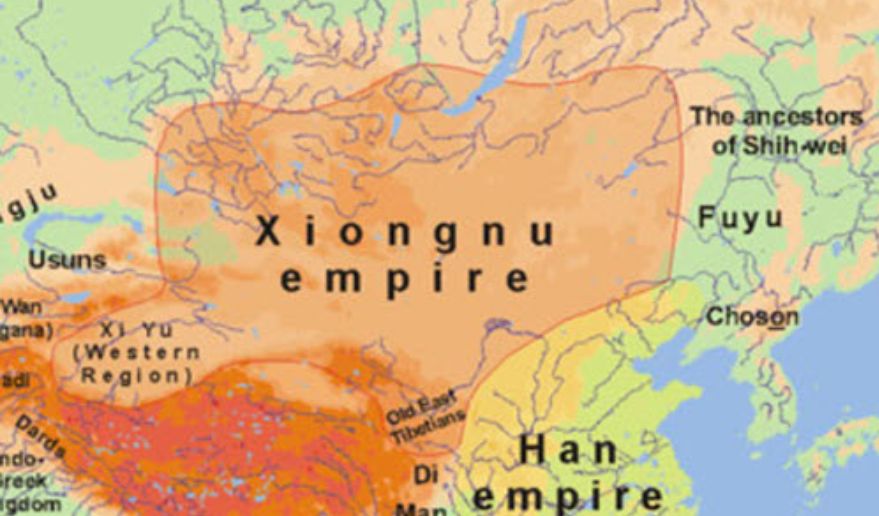

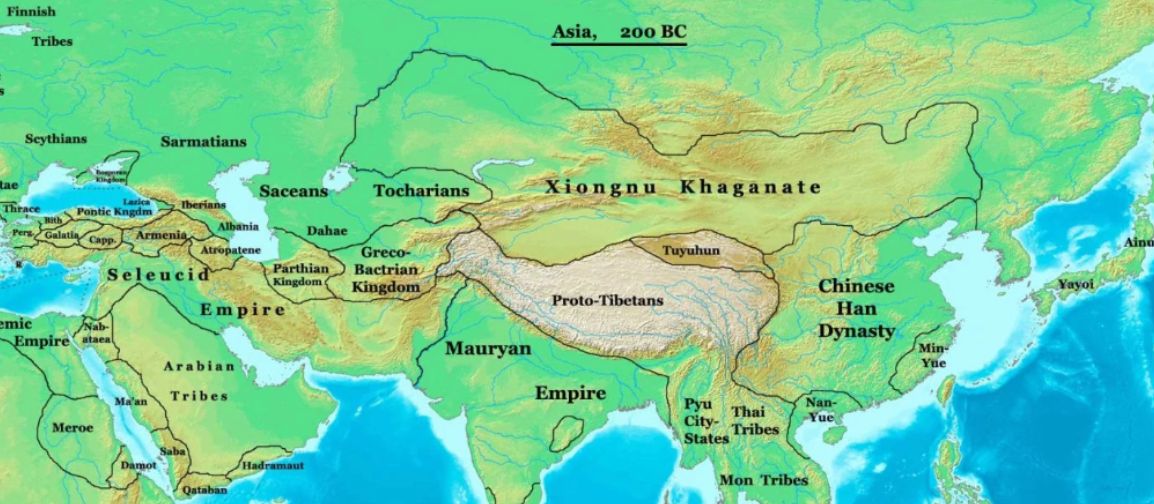

Xiongnu, Huns and the End of Empire

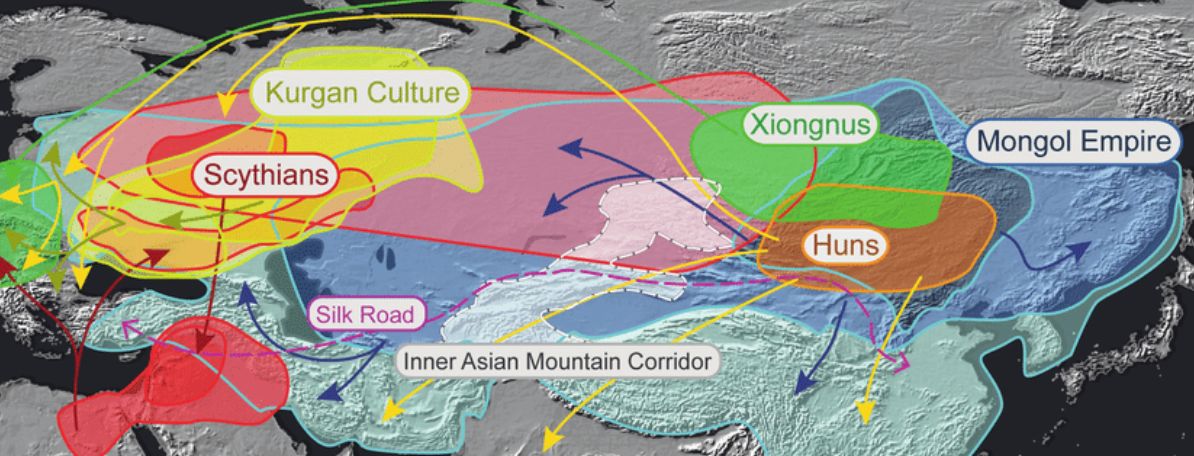

In the fourth century

AD, an offshoot of the Xiongnu (Hun-nu) nation moved west onto the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. The Xiongnu (Chinese: 匈奴; Wade–Giles: Hsiung-nu) were a tribal confederation

of nomadic peoples who inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd

century BC to the late 1st century AD.

These Xiongnu nomadic pastoral people who at the end of the 3rd

century BCE formed a great tribal league that was able to dominate much of

Central Asia for more than 500 years. China’s wars against the Xiongnu, who were a constant threat to the country’s

northern frontier throughout this period, led to the Chinese exploration and

conquest of much of Central Asia.

It is these Xiongnu that is known to the Romans as the Huns who

defeated the Alani and conquered the populous Gothic realms in Eastern Europe.

In the process, they caused a significant refugee movement into Europe, which

destabilized the Roman Empire. Over the following century, the Huns launched

devastating attacks on Roman territory that destroyed frontier defenses and

eventually caused the downfall of the Western Roman Empire (AD 476).

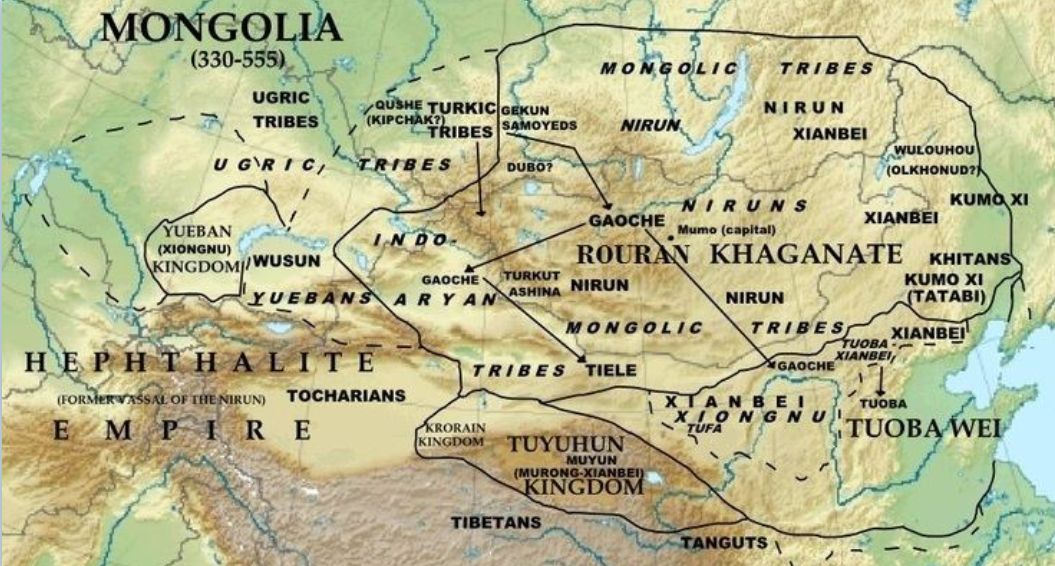

This westward

movement of Xiongnu people occurred in a period of

Chinese history known as the Sixteen Kingdom Era (AD 304–439). The Sogdian

Letters record how the resurgent Xiongnu (Hun)

overran northern China in AD 312 and

sacked the walled capital Luoyang.2 The attack was led by a southern Xiongnu faction who called themselves the ‘Han Zhao’

because their leaders claimed to be descendants of the Han dynasty princess

that Chanyu Modu had received as his royal bride.

With an army of 50,000 steppe warriors, the Han Zhao also sacked the former

capital Chang’an, capturing two Jin Emperors during

the course of their campaigns (AD 304–319).3

As a consequence, the

northern domains of China fractured into numerous small kingdoms formed from

various nations and dynasties that had once been Chinese subjects. Some of

these states and their successors existed in steppe territories ruled by

warlords descended from the Southern Xiongnu. This

included the Northern Lang in the Hexi Corridor, the Northern Tiefu of Inner Mongolia, and the Kingdom of Xia in the

Ordos Loop. Between AD 351 and AD 376, a robust frontier regime known as Former

Qin began to conquer its warring rivals, but it was the Northern Wei that

achieved overall victory and established control over northern China (AD

386–534).

The Northern Wei

governed with Chinese-style administration and promoted their regime using

Buddhist ideologies. But their ruling dynasty was descended from Xianbei warlords, so the system possessed numerous skilled

cavalry that could campaign on the steppe. Their rise to power prompted a

migration of Xiongnu

factions westward towards the Caspian steppe. A Chinese text called the Weishu (History of

the Northern Wei) records that by the start of the fourth century ‘the remains of the Xiongnu

descendants’ were to be found northwest of the steppe-dwelling Rouran who by

that period occupied most of Central Asia.4

One of these Xiongnu groups called themselves the ‘White’ clan which was

the symbolic color of the West in their ancient culture.5 The Roman historian

Ammianus confirms that this subgroup followed a migration route into

Transoxiana where they threatened lands subject to the Sassanid Persian Empire

(AD 356).6

The Persians called

these invaders ‘Chionites’, but the Indians referred

to them as ‘Huna’.7 The Chionites quickly overran Bactria, and the Byzantine

scholar Faustus records how in AD 368 the Persian King recruited Armenian

troops into his armies to try to defend his eastern provinces.8 Writing in the

sixth century the Byzantine scholar Procopius calls these invaders ‘the

Hephthalite Huns, who are called White

Huns’ and reports that ‘they do not intermix with any of the other Huns known

to us.’9 He claims that the Huns did not

seem to be ‘Scythians’ and had no ‘regal government’. 10 Claudian confirms that

the Huns came from somewhere beyond the ‘extreme eastern borders of Scythia’.11

Ammianus explains: ‘A hitherto unknown race of men has arisen from some hidden

recess of the earth and like a tempest of snows from the high mountains they

seize or destroy everything in their way.’12

Another subgroup of Xiongnu (Huns) first appears in Roman accounts in AD 370

when they arrived in lands to the north of the Caspian Sea and crossed the

Volga River. Coming from unknown territories, these Huns rapidly conquered the

Alani and Goths, who occupied steppe lands north of the Black Sea (Scythia).

Zosimus reports that ‘a barbarous nation, which had remained unknown until this

time, suddenly made its appearance and attacked the Scythians beyond the Ister (Danube).’

The Huns had migrated

to seek land, and they arrived on the Pontic steppe with their wives, children,

horses, and wagons.13 Zosimus explains that their warriors ‘were not capable of fighting on foot, rarely

walked, could not fix their feet firmly on the ground, but live perpetually,

and can even sleep, on horseback’.14 According to Roman accounts they possessed superior

horses, more considerable skill at archery, and demonstrated more persistence

in their attacks than other steppe nations.

Jordanes, the

sixth-century Byzantine historian, describes them as being ‘tanned with a large

head that is not distinct. Their eyes are small, resembling a pinhead.’ He

reports that male Huns ritually scarred their faces with blades as displays of

mourning enacted at funeral services.15 Procopius also suggests that the Huns

had a distinctive haircut that was copied by the riotous gangs who watched

chariot races in Constantinople. The Hun haircut was achieved by ‘clipping the

hair short on the front of the head down to the temples, then letting it hang

down in great length and disorder at the back’.16

Jordanes reports that

the Huns were ‘short in stature with fast physical movements, alert horsemen,

broad-shouldered and primed in the use of bow and arrow, with firm-set necks held erect with

pride’.17Ammianus offers a similar account, describing the Huns as possessing

‘compact bodies, strong limbs, and thick necks.’

He suggests they were

disfigured by a lifetime of horse-riding and walked awkwardly when they

dismounted.18 Sidonius compared the Huns to the centaurs of classical

mythology, describing how they learned to ride as soon as they could walk.

He reports, ‘You

would think that the limbs of man and horse are fused so firmly does the rider

always move with the horse; other people are carried on horseback, but these

people live there.’19 Ammianus reports that even their war councils were

conducted while mounted and ‘when deliberation is required regarding important

matters, they all consult as a common body on horseback.’20

Hunnic horses were

considered superior to the western breeds used by Scythians on the Pontic

Steppe and Roman cavalry in Europe. A Roman named Vegetius wrote a study on

veterinary medicine in which he lists the characteristics of these horses. They

had ‘large hooked heads, protruding eyes, narrow nostrils, broad jaws, strong and stiff necks, manes hanging

below their knees, overlarge ribs, curved backs, bushy tails, great strength in

their cannon bones, small pasterns,

wide-spreading hooves, hollow loins, angular rumps without fat or

muscles, a back stature that is long

rather than high, drawn in belly and large bones.’ This accurately describes

the horses used by Central Asian steppe nations.

Roman horses were

expensive to maintain since they had to be kept warm in stables and required

frequent veterinary attention. Vegetius explained that Hunnic horses did not

need barns and could endure more significant cold and hunger without distress.

They were also longer-lived and less prone to injury than their Roman

counterparts. Hunnic breeds were also better able to bear wounds due to their

quiet and sensible temperament. Therefore in the opinion of Vegetius, they held ‘first place among horse breeds in their

fitness for war’.21

Skilled Hun bowmen

could outpace and outmaneuver armored Sarmatian riders who specialized in

cavalry charges carrying cumbersome lances. Jordanes reports that the Alani

‘equaled the Huns in battle but had different cultures, manners, and

appearance. The Huns exhausted them by their incessant attacks and subdued

them.’22 Zosimus confirms that their warriors overcame the western steppe

dwellers with continual attacks and ‘by the rapidity with which they wheeled

about their horses, by the suddenness of their excursions and retreats,

shooting as they rode they caused a great slaughter among the

Scythians.’23Claudian refers to their attacks which seemed ‘disorderly, but had

incredible swiftness, allowing the Huns to often return to the fight when

little expected’.24

Ammianus describes

how Hunnic warriors rode into battle in wedge-shaped masses, while ‘their

medley of voices makes a savage noise.’ They were ‘lightly equipped for swift

motion and unexpected action, they purposely divide suddenly into scattered

bands and attack, rushing about in disorder here and there, dealing terrific

slaughter.’ The Huns surpassed all other warriors in the skill of their

archery, but when the opportunity came, ‘they can gallop over the intervening

ground and fight hand-to-hand with swords.’ They also lassoed their enemies

throwing ‘strips of cord plaited into nooses over their opponents, entangling

and binding their limbs so they cannot ride or walk.’25 Unlike the Chinese who

possessed sophisticated crossbows, the Goths and Romans had no projectile

weaponry that could easily outrange and target mounted Hunnic archers.

Ammianus records that

within a few years the Huns ‘had overrun the territories of the Alani,’ they

‘killed and plundered many of them, then joined the survivors to themselves in

a treaty of alliance.’26 This gave Hunnic armies the Sarmatian cavalry equipped

with scale and chain mail armor. After suppressing the Alani, the Huns moved

west to attack the Goths, who by the fourth century AD were a populous nation

inhabiting agricultural territories stretching from the Baltic coast to the

northern Black Sea. The Goths on the Pontic steppe had adopted cavalry

practices, but they fought with spears instead of the sophisticated reflex bows

used by the Scythians. Procopius explains that Gothic bowmen ‘entered battle on

foot under cover of heavily armed men’.27

Gothic spearmen could

not ride faster than Hunnic warriors, and even in close combat, Goth riders

could find it challenging to overcome Huns equipped with helmets and lamellar

armor. Procopius describes how an elite Hun soldier ‘was surrounded by twelve Goths

carrying spears whom all struck at him at once, but his corselet withstood the blows, and he was not

seriously injured until one of the Goths

succeeded in hitting him from behind, in a place where his body was

unprotected, above the right armpit’. This Hun was only wearing a helmet and

jacket-like coat of chain or lamellar armor since another spear-thrust wounded

his exposed thigh.28

Roman sources suggest

that it was challenging to unseat or kill a mounted Hunnic warrior. Sidonius

describes a Hun who was speared by a lance, ‘transfixed, his corselet was

pierced front and back so that blood came throbbing through the two holes.’29

Some Huns carried shields, and Sozomen describes a

Hunnic warrior leaning on his shield, ‘as was his custom when parleying with

his enemies’.30

Grave finds suggest

that some Huns practiced the steppe custom of artificial cranial deformation

and by binding the heads of their babies they encouraged the infant’s skull to

develop in an elongated shape.31 Some Romans assumed that this practice was connected

with warfare, to flatten the face and make it easier for warriors to wear

helmets with broad nose-guards.32 A few wealthy Huns gilded their armor,

perhaps emulating the customs of the Aorsi who wore

gold ornaments.33 Asterius of Amasia reports that ‘the armor of the barbarians

is ostentatious’ and describes a steppe chief on the Black Sea coast who

offered his gilded cuirass to a Christian representative.34

When the Huns

defeated the Gothic kingdoms, tens of thousands of refugee Goths and Alani fled

south to seek protection in the Roman Empire. Ammianus reports that ‘exhausted

by a lack of necessities they looked for a new homeland far from the savages

and after much deliberation, they chose Thrace as a suitable refuge, because it

has very fertile soil and because it is separated by the mighty flood of the Danube from the lands

exposed to war.’ The Gothic realms were allied to the Roman Empire, and

Ammianus records how a large part of the defeated nation suddenly appeared on

the banks of the Danube asking admittance into imperial territory.35 Zosimus

reports, ‘The surviving Scythians (Goths and

Alani) were compelled to abandon their homelands to the Huns and cross

the Danube, they, therefore, appealed to

the Emperor to receive them, promising to

serve faithfully as soldiers.’ Tens of thousands of Goths and Alani were

admitted into the frontier provinces along with their families, but despite

confiscation orders, many were able to bribe officials and cross the Danube

carrying weapons.36

These refugees were

confined to camps near the frontier, but they were offered limited supplies

while they were systematically exploited and mistreated by various Roman

officials. As a result, the Gothic refugees rebelled and overran the Balkan

countryside with raiding parties (AD 376–378). In AD 378 the Eastern

Emperor Valens marched against the

Gothic army, but their steppe cavalry outmaneuvered him at the Battle of

Adrianople.37 The Emperor was killed along with most of the Eastern Field Army

while their enemies ‘plundered the dead bodies and armed themselves with Roman

equipment’.38

The Goths dominated

imperial politics throughout the following century as their various

nation-states crossed the Empire to seize territories from imperial

control. They overran rich agricultural

territories, demanded tribute from Roman cities, and captured various armories

and imperial workshops. The Visigothic chief Aleric

boasted that the Roman province of Thrace forged spears, swords, and helmets

for his warriors.39 Meanwhile, the Huns moved westwards towards the grasslands

of Hungary on the Danube frontier. In a few decades, they had conquered and

occupied a territory stretching over 1,700 miles from the Roman Danube to the

Volga River.

The Threat to Rome

Theodosius I was the

last Emperor to rule a unified Roman regime. In AD 393, he placed his

9-year-old son on the throne of the Western Empire under the guidance and

protection of a senior general named Flavius Stilicho. Theodosius was then

succeeded by his eldest son Arcadius who ruled the Eastern Empire from a

bureaucratic court, while the western government fell under the authority of

generals assisted by Gothic and Germanic warlords brought into regular imperial

service.

Authorities in the

Western Roman Empire sought alliances with the Huns, who occupied large parts

of Eastern Europe and the Pontic-Caspian steppe. By contrast, the Eastern Roman

Empire was a target for Hunnic raids, aggression, and extortion. In AD 395, the

Huns sent an army through passes in the Caucasus Mountains to raid the Eastern

Roman Empire. Jerome describes the sudden terror of these attacks as

‘everywhere their approach was unexpected as their speed overtook any rumor of

their coming and they spared neither religion, rank nor age.’ Hunnic armies

entered Armenia and rode south to plunder Syria, as the population of Antioch

and Tyre retreated into their cities. Roman

authorities suspected that the Huns might be planning to rob gold from

Jerusalem and wealthy citizens fled onto ships to avoid capture or death.40

Jerome confirms the impact of these raids when he writes that ‘the soldiers of

Rome who are conquerors and lords of the world are subdued, tremble and

withdraw in fear at the sight of those who cannot easily walk on foot.’41

The Huns then turned

their attention west and subjugated populations in central Germany, prompting a

further movement of displaced Germanic peoples into the Western Roman Empire.

In AD 405 tens of thousands of Suebians, Vandals, and

Alani crossed the Rhine frontiers along with their families to settle in Roman

Gaul. Up to 80,000 Vandals migrated through Spain and in AD 429 they crossed

Antioch and Tyre retreated into their cities. Roman authorities

suspected that the Huns might be

planning to plunder gold from Jerusalem and wealthy citizens fled onto ships to

avoid capture or death.42Jerome confirms the impact of these raids when he

writes that ‘the soldiers of Rome who are conquerors and lords of the world are

subdued, tremble and withdraw in fear at the sight of those who cannot easily

walk on foot.’43

The Huns then turned

their attention west and subjugated populations in central Germany, prompting a

further movement of displaced Germanic peoples into the Western Roman Empire.

In AD 405, tens of thousands of Suebians, Vandals,

and Alani crossed the Rhine frontiers along with their families to settle in

Roman Gaul. Up to 80,000 Vandals migrated through Spain and in AD 429 they

crossed into North Africa to seize the fertile farmlands that supplied grain to

Rome.44

During this period,

military leaders in the Western Roman Empire recruited Hunnic warriors into

imperial service as the elite bodyguards of senior commanders. The Western Emperor Honorius (AD 393–423)

maintained 300 Huns in the Italian capital Ravenna and Stilicho, the Magister Militum (‘Master of Soldiers’), was protected by a personal

bodyguard of Hunnic troops.45 In AD 409, the Emperor summoned a mounted force,

including 10,000 Hunnic allies, to help defend Italy from an army of Visigoths

who were threatening Rome. Zosimus suggests that the Romans found it difficult

to feed and supply this number of horse riders and the riders withdrew allowing

the Visigoths to sack Rome the following year.46 In AD 425, a Roman commander named Flavius Aetius

requested the support of a Hunnic army to decide a succession dispute in the

Western Roman Empire. He led 60,000 allied Hunnic warriors into Northern Italy

before negotiating a peace that allowed him to claim the title Magister

Militum.47 By this period Hunnic armies incorporated the most influential

military traditions of their subject peoples, and Jordanes describes their

varied appearance including ‘Suebi (Germans) fighting on foot, Huns with bows

and the Alani forming-up into a heavy-armed battle-line’.48

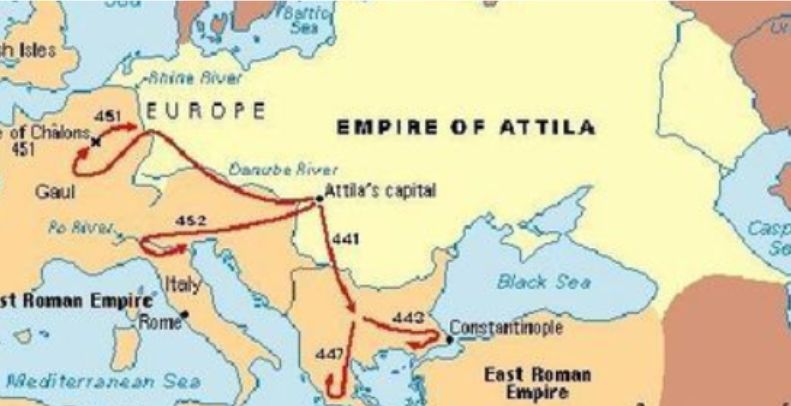

In AD 445, a chief

named Attila was proclaimed king of the Huns and, after unifying his subject

peoples, ‘he gathered a host of the other tribes under his power.’ Jordanes

describes Attila as ‘short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head; his

eyes were small, his beard thin and greying, and he had a flat nose and tanned

complexion.’ He was said to be ‘enthusiastic for war, but restrained in

action, mighty in counsel, gracious to

suppliants and lenient to those who were received into his protection’.49

Under the command of

Attila, Hunnic armies reduced the political and military strength of the Roman

regime and caused the collapse of the Western Empire. Like the Xiongnu, the Huns wanted to dominate and extract wealth

from their imperial rivals, rather than conquer or destroy them. It was said

that when Attila captured the Italian city of Milan, he saw a painting of the

Roman Emperors sitting upon golden thrones and Scythians lying dead before

their feet. He ordered the image redrawn to depict ‘Attila upon a throne and

the Roman Emperors heaving sacks upon their shoulders and pouring out gold

before him’.50 Attila’s funeral oration was reported to have praised him as the

chief who ‘held the Scythian and German realms, terrified both Roman Empires,

captured their cities and placated by their appeals, took yearly tribute in

place of plunder’.51

Attila’s attacks on the

Eastern Roman Empire began in AD 441 when Hunnic armies crossed the Danube

frontier and plundered the Balkans. The Huns had with them Roman captives with

the engineering skills required to bridge rivers. They also brought numerous

battering-ram siege engines that they mounted on large steppe-wagons. If

threatened by attack, these massive timber wagons could be quickly drawn into

formation to create a fortress-like wooden stronghold. Priscus describes the

siege of a fortified Roman city called Naissus when

the Huns drove ‘a vast number of siege engines’ against the walls. Archers

fired from wicker and hide-protected portholes in these wagons, forcing the

defenders from the battlements, as the battering-rams were rolled forward.

These rams consisted of a sizeable metal-headed beam fixed to chains so that it

could be drawn back with ropes, then swung forward with pendulum force. The

walls of Naissus were battered down at numerous

points, allowing the Huns and their Gothic allies to scale the rubble with ladders

and plunder the city.52 These sieges were rapid operations conducted with

overwhelming force, and in AD 443, the Huns threatened but did not attack, the heavily-fortified imperial capital of

Constantinople (Byzantium). Tens of thousands of Roman subjects, including many

skilled urban tradespeople, were seized in their raids and conveyed to the

Hunnic homelands in Hungary and the Pontic steppe. A Roman chronicle describes

the conflict as ‘a new disaster for the east:

more than seventy cities were sacked while no assistance came from the

troops of the Western Empire’.53

The Eastern Empire

bought peace terms with the Huns for 6,000 pounds of gold and an agreement that

a further 2,100 pounds of gold per annum would be given as tribute (equivalent

to 8.4 million sesterces of first-century currency).54 In addition, thousands

of Roman prisoners were returned at a ransom of 8 gold solidi per person.55

According to Priscus, ‘these tributes were very heavy, as many resources and

the imperial treasuries had been exhausted.’56 Priscus reports: ‘The Romans

pretended that they had made the agreements voluntarily. But because of the

overwhelming fear which gripped their commanders, they were compelled to accept

gladly every injunction, however harsh, in their eagerness for peace.’57

Despite these protests, the Eastern Empire could pay further tribute, and John

Lydus reports that in AD 457 the treasury preserved 100,000 pounds of

gold, ‘which Attila, the enemy of the

world, had wanted to take’.58

In AD 449, Priscus

was selected by the government of the Eastern Roman Empire to lead an embassy

to the court of Attila. He traveled to one of the Hunnic capitals north of the

Danube, which resembled a vast wood-built village the size of a Roman town. Attila’s

royal residence was constructed from close-fitting polished timbers and

ornamental wooden boards and, although it had a perimeter adorned with towers,

the complex was built ‘for beauty rather than protection.’ Priscus reports that

a Roman captive taken from the city of Sirmium had

made a heated bath-house at the site, confirming the new engineering skills

then available to the regime. Attila received envoys and petitions and oversaw

legal cases in his royal hall. Priscus records that one of his royal

secretaries was a Roman administrator named Rusticius

who was another war-captive, employed by the Huns because of ‘his skills in

speech and composing letters’.59 Attila was also promoting his regime using

motifs from the Sarmatian religion and claimed to have discovered the sacred

sword of the classical war god Mars (Ares).60

Another incident

indicates the Hunnic capacity for acculturation. Priscus met a former Roman

merchant in the Hunnic capital who spoke fluent Greek but was dressed in full

‘Scythian attire’ and cut his hair in their distinctive style. The Greeks

explained he had been a wealthy inhabitant of Viminacium

near the Danube River, but when the city was stormed, he was captured and

brought into Hunnic service.

He had ‘fought

bravely in battles against the Romans’ and with the spoils ‘he had obtained his

freedom according to the law of the Scythians.’ He could have returned to the

Empire, but he married a Scythian woman, had children by his foreign wife and

continued to serve the Huns.61

While Priscus was

attending the Hunnic court, he spoke to visiting envoys from the Western Roman

government about the threat posed by Attila. They explained to Priscus that ‘no

one who ruled over Scythia or any other land had achieved such great things in

such a short time.’ They warned that Attila ‘rules all of Scythia, makes the

Romans pay tribute and is aiming at more significant achievements for he wants

to engage the Persians and enlarge his territories’. The envoys explained that

Media was no great distance from the Hunnic regions, and the Huns knew the main

routes through the Caucasus Mountains. They believed that Attila, ‘with little

difficulty and only a short journey, would subdue the Medes, Parthians, and

Persians and force them to submit to the payment of tribute. For he has a

military force which no nation can resist.’ One of the envoys from Rome named Constantiolus warned that if Persia fell to the Huns, then

Attila would dictate ruling terms on the Western Roman Empire. Constantiolus claimed, ‘At present, we bring Attila gold

for the sake of his rank, but if he overwhelms the Parthians, Medes, and

Persians, he will no longer endure the rule of independent Romans.’62 But

contrary to Roman expectations the Huns

did not engage the Persian Empire as their next military target. In AD 450, Attila received a pretext for war

against the Western Roman Empire.

Honoria, the

disgraced half-sister of the Emperor Valentinian III, sent a marriage proposal

to Attila. This union would have given Attila controlling interests in the

imperial succession, but the marriage was refused by the Roman court, who

insisted that Honoria marry an aging senator. At the same time, the Eastern

Roman Empire withheld the annual gold tribute that it had agreed to pay to the

Huns.

Priscus reports that

‘Attila was undecided whom he should attack first, but resolved to begin with

the greater war and advance against the West since his fight there would be

against Goths and Franks’ who had fled Hunnic rule for Roman protection.63

In AD 451, Attila

attacked the Western Roman Empire with a Hunnic army supported by large numbers

of subject Goths (Ostrogoths) and Germans. His invasion force would have

included more than 60,000 warriors, making it the largest field-army operating

in the western world. Attila plundered cities in Gaul and ‘launched a fierce assault with his

battering-rams’ on the heavily fortified town of Orleans.64 In response, the Western Roman

regime allied with the Alani, Franks,

and Visigoths who occupied large parts of Gaul and viewed the Huns as their

traditional enemies. The two armies fought a large-scale engagement at the

Battle of the Catalaunian Plains that ended with a

stalemate and the withdrawal of the Hunnic army from Gaul.65

The following year

the Hunnic army crossed the Alps and sacked the significant cities in northern

Italy before threatening Rome itself (AD 452). On this occasion, the Roman

regime could not obtain support from their Germanic allies, and the remaining

imperial units were unable to manage an adequate defense. Jordanes describes

how the Hunnic army attacked the fortified city of Aquileia: ‘Bringing forward

all manner of war-engines, they quickly forced their way into the city,

plundered it, divided the spoils and so cruelly devastated the place that

scarcely anything remained.’ He claims that the invaders ‘devastated the most

significant part of Italy’ before approaching Rome.66 Pope Leo was chosen as

the envoy to Rome, and the western government was forced to agree on peace

terms that made their empire tributary to the Huns. Attila also reasserted his

claim to an imperial marriage alliance and demanded the government surrender

the princess Honoria, ‘with her due share of the royal wealth’.67

The campaign had

exhausted the Roman capacity for war, and the regime was open to invasion and

exploitation by further foreign powers. With the Western Empire subdued, Attila

returned with his army to his Hungarian realm to plan new campaigns against the

Visigoths and Alani.68 He was also anticipating conflict with the Eastern Roman

Empire as it was withholding the promised tribute payments to the Hunnic court.

But in AD 453, on the night of his marriage to a German princess named Ildico, Attila suddenly died from a brain hemorrhage .69

The fate of Honoria is not known, and she may have remained in Rome under

imperial custody. The death of Attila caused subject nations to rebel and his

empire disintegrated in a series of conflicts. The Hunnic threat diminished,

but by this period, large parts of the Western Roman Empire were under the

direct rule of Germanic nations who had conquered relevant territories or been

given land in return for military service. The last ever Emperor of Rome was a

boy named Romulus Augustus, who was deposed by a Germanic king named Odoacer in

AD 476. It had taken less than a century for a significant steppe incursion

with an influx of foreign refugees to destabilize, undermine, and destroy the

Roman Empire.

In antiquity, the

Huns were the largest and most significant population group to have traveled

across the steppe from the Far East to the Roman frontiers, a journey of more

than 5,000 miles. But during the long history of the silk routes, many other

unnamed, impoverished, or dispossessed individuals passed through the empires

of Central Asia as the consequence of conflict, slavery, or commerce.

Archaeologists excavating the ancient site of an imperial estate at Vagnari in southern Italy unearthed the graves of slave

workers who had been involved in textile production during the first century

AD. DNA testing of skeletal remains revealed that one of the men buried in the

plot had Far Eastern ancestry inherited from his mother.70

In spite of all the

wealth associated with the silk routes, his sole possession was a plain wooden

food bowl, placed next to his body for use in the afterlife. Whomever this man

was and however his ancestors had found themselves in the very center of the

Roman Empire, he had ended his days as a slave and was buried in a simple grave

on a bleak hillside.

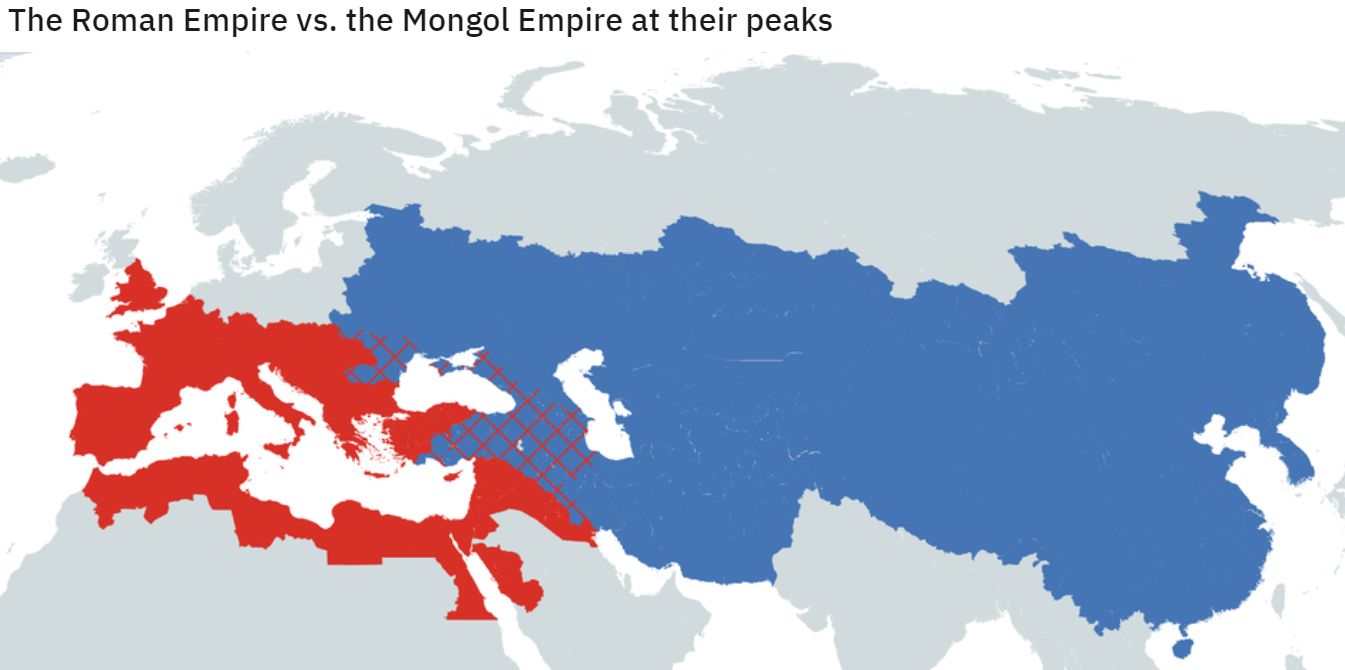

Yet while the Chinese

empire recovered from its numerous fragmentations and invasions and remained a

unified nation. The explanations why the Roman Empire did not recover from its

fall. As we have seen, in the middle of the

second century, the Romans controlled a huge, geographically diverse part of

the globe, from northern Britain to the edges of the Sahara, from the Atlantic

to Mesopotamia. The generally prosperous population peaked at 75 million. Eventually,

all free inhabitants of the empire came to enjoy the rights of Roman

citizenship.

Five centuries later,

the Roman empire was a small Byzantine rump-state controlled from

Constantinople, its near-eastern provinces lost to Islamic invasions, its

western lands covered by a patchwork of Germanic kingdoms. Trade receded,

cities shrank, and technological advance halted. Despite the cultural vitality

and spiritual legacy of these centuries, this period was marked by a declining

population, political fragmentation, and lower levels of material complexity.

This violent sequence

of eruptions triggered what is now called the “Late

Antique Little Ice Age” when much colder temperatures endured for at least

150 years. This phase of climate deterioration had decisive effects in Rome’s

unraveling.

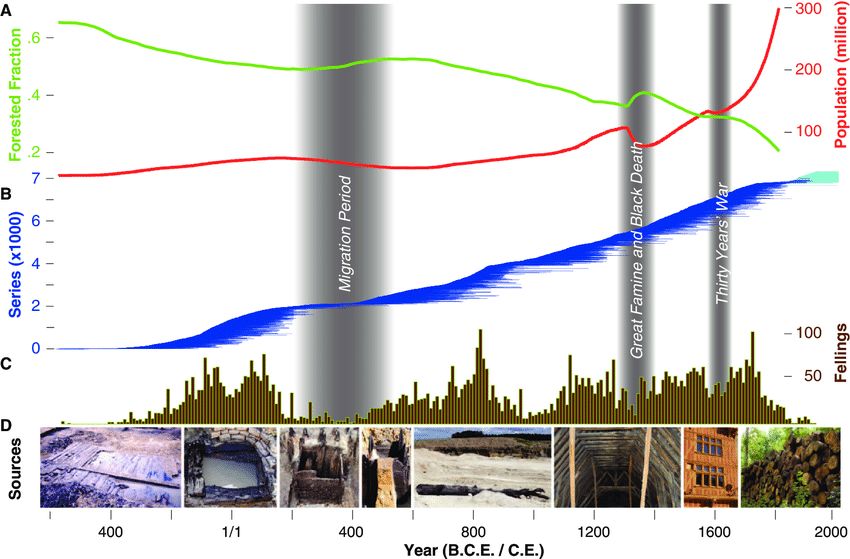

(A to D) Evolution of

central European forest cover and population from (A), together with oak sample

replication (B), their historical end dates at decadal resolution (C), and

examples of archaeological (left), subfossil, historical, and recent (right) sample

sources (D).

Claims that the

decisive factor in Rome’s biological history was the arrival of new germs the

Antonine plague the Plague of Cyprian and in the sixth century, the bubonic

plague, have

recently been contested.

Footnotes upon request you can write to me at

ericvandenbroeck1959@gmail.com

For updates click homepage here