Where we covered this subject on 19 Oct. 2020,

on 14 February, China analyst Adam Ni (who among others is editor of The China Story) issued a poll

asking what will be human cost in casualties in a potential cross-strait

conflict on all sides (Taiwan, China, US & allies)? With still a day to go,

317 people had voted already, with 47.6 % expecting millions of death and only

18% hundreds of thousands. By the end of the 15e, now counting 2,016

votes, the 47.6 % section turned into 61.9% of the votes, the latter obviously

presuming the US would get involved.

Several commentators

furthermore suggested that Taiwan is the key link in the first island chain. If

the CCP takes over Taiwan, they not only get TSMC, but their submarines also

gain access to the pacific and west coast of the US. If we lose TW to A totalitarian

China, we lose all. The broader and more relevant question covers China's

geopolitical influence into the Pacific and control of the S. China sea with

1/3 of maritime trade. It's not just about Taiwan and democratic values...

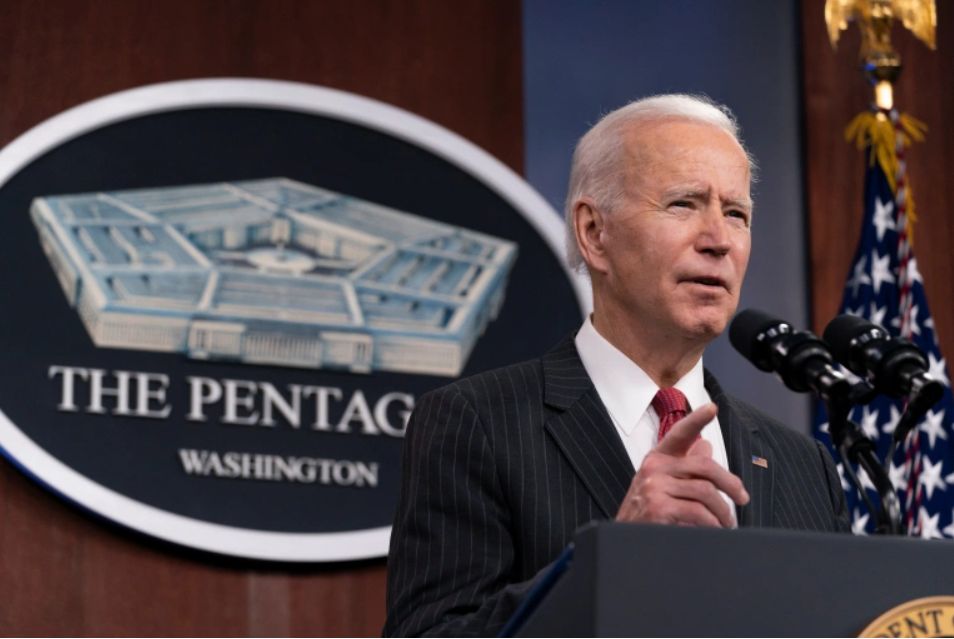

Elsewhere, addressing

the virtual Munich Security Conference in his first international foreign

policy speech on 19 Feb., President Biden says the

world must prepare for ‘long-term’ competition with China.

Whereas Joe

Biden-the-candidate publicly favored a more pragmatic and less confrontationist

policy toward China, short of the continuing trade war implemented by his

predecessor, Biden-the-president appears to have decided to adopt the very lens

the previous administration used to make its China policy, with important

caveats. It seeks allies across Asia and appears to be acting

with deliberation but not backing away from confrontation.

As it stands, the

Biden administration is moving quickly to build on the Trump administration legacies

it finds to be practical. But the Trump administration failed to get any

traction, probably because of the unpredictable behavior of the president and

his maverick Secretary of State. On the other hand, the Biden administration

may be able to get more support because of its better reputation and enhanced

predictability.

Where will the China/US competition lead the world?

On 28 Jan., China

issues issued a statement making it clear that it is impossible to ask for

China's support

in global affairs while interfering in its domestic affairs and undermining

its interests. Biden says that his recent call with China's Xi

Jinping was 'robust,' but

China doesn't seem too concerned.

Having earlier

commented on China's Belt and Road Initiative,

the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is increasingly confident

that by the decade’s end, China’s economy will finally surpass that of the

United States as the world’s largest in terms of GDP at market exchange rates.

Western elites may dismiss the significance of that milestone; the CCP’s

Politburo does not. For China, size always matters. Taking the number one slot

will turbocharge Beijing’s confidence, assertiveness, and leverage in

Washington's dealings. It will make China’s central bank more likely float the

yuan, open its capital account, and challenge the U.S. dollar as the main

global reserve currency.

Beijing’s assertive agenda

Meanwhile, China

continues to advance on other fronts as well. A new policy plan, announced last fall, aims to allow China to dominate

in all new technology domains, including artificial intelligence, by 2035. And

Beijing now intends to complete its military modernization program by 2027

(seven years ahead of the previous schedule), with the main goal of giving

China a decisive edge in all conceivable scenarios for a conflict with the

United States over Taiwan. A victory in such a conflict would allow President

Xi Jinping to carry out a forced reunification with Taiwan before leaving power—an

achievement that would put him on the same level within the CCP pantheon as Mao

Zedong.

Washington now will

have to decide how to respond to Beijing’s assertive agenda. If it were to opt

for economic decoupling and open confrontation, every country in the world

would be forced to take sides, and the risk of escalation would only grow.

There is understandable skepticism among policymakers and experts regarding

whether Washington and Beijing can avoid such an outcome. Many doubt that U.S.

and Chinese leaders can find their way to a framework to manage their

diplomatic relations, military operations, and activities in cyberspace within

agreed parameters that would maximize stability, avoid accidental escalation,

and make room for both competitive and collaborative forces in the

relationship. The two countries need to consider something akin to the

procedures and mechanisms that the United States and the Soviet Union put in

place to govern their relations after the Cuban missile crisis—but in this

case, without first going through the near-death experience of a barely avoided

war.

In the United States,

few have paid much attention to the domestic political and economic drivers of

Chinese grand strategy, its content, or how China has been operationalizing it

in recent decades. The conversation in Washington has been all about what the

United States ought to do, without much reflection on whether any given course

of action might result in real changes to China’s strategic course. A prime

example of this type of foreign policy myopia was an address that

then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo delivered last July. He effectively called for the overthrow of the CCP. “We, the

freedom-loving nations of the world, must induce China to change,” he declared,

including by “empower[ing] the Chinese people.”

The South China Sea and China's long view

The only thing that

could lead the Chinese people to rise against the party-state, however, is

their own frustration with the CCP’s poor performance on addressing

unemployment, its radical mismanagement of a natural disaster (such as a

pandemic), or its massive extension of what is already intense political

repression. Outside encouragement of such discontent, especially from the

United States, is unlikely to help and quite likely to hinder any change.

Besides, U.S. allies would never support such an approach; regime change has

not exactly been a winning strategy in recent decades. Finally, bombastic

statements such as Pompeo’s are utterly counterproductive because they

strengthen Xi’s hand at home, allowing him to point to the threat of foreign

subversion to justify ever-tighter domestic security measures, thereby making

it easier for him to rally disgruntled CCP elites in solidarity against an

external threat.

That last factor is

significant for Xi because one of his main goals is to remain in power until

2035, by which time he will be 82, the age at which Mao passed away. Xi’s

determination to do so is reflected in the party’s abolition of term limits,

its recent announcement of an economic plan that extends all the way to 2035,

and the fact that Xi has not even hinted at who might succeed him even though

only two years remain in his official term. Xi experienced some difficulty in

the early part of 2020, owing to a slowing economy and the COVID-19 pandemic,

whose Chinese origins put the CCP on the defensive. But by the year’s end,

official Chinese media were hailing him as the party’s new “great navigator and

helmsman,” who had prevailed in a heroic “people’s war” against the novel coronavirus. Indeed, Xi’s standing

has been aided greatly by the pandemic's shambolic management in the United

States and several other Western countries, which the CCP has highlighted as

evidence of the Chinese authoritarian system's inherent superiority. And just

in case any ambitious party officials harbor thoughts about an alternative

candidate to lead the party after Xi’s term is supposed to end in 2022, Xi

recently launched a major purge—a “rectification campaign,” as the CCP calls

it—of members deemed insufficiently loyal.

Meanwhile, Xi has

carried out a massive crackdown

on China’s Uighur minority in the region of Xinjiang; launched campaigns of

repression in Hong Kong, Inner Mongolia, and Tibet; and stifled dissent among

intellectuals, lawyers, artists, and religious organizations across China. Xi

has come to believe that China should no longer fear any sanctions that the

United States might impose on his country or individual Chinese officials in

response to violations of human rights. In his view, China’s economy is now

strong enough to weather such sanctions, and the party can protect officials from

any fallout, as well. Furthermore, unilateral U.S. sanctions are unlikely to be

adopted by other countries for fear of Chinese retaliation. Nonetheless, the

CCP remains sensitive to the damage that can be done to China’s global brand by

continuing revelations about its treatment of minorities. That is why Beijing

has become more active in international forums, including the UN Human

Rights Council, where it has rallied support for its campaign to push back

against long-established universal norms on human rights while regularly

attacking the United States own alleged abuses of those very norms.

Xi is also intent on

achieving Chinese self-sufficiency to head off any effort by Washington to

decouple the United States’ economy from that of China or to use U.S. control

of the global financial system to block China’s rise. This push lies at the

heart of what Xi describes as China’s “dual

circulation economy”: its shift away from export dependency and toward domestic

consumption as the long-term driver of economic growth and its plan to rely on

the gravitational pull of the world’s biggest consumer market to attract

foreign investors and suppliers to China on Beijing’s terms. Xi also recently

announced a new technology R & D strategy and manufacturing to reduce

China’s dependence on importing certain core technologies, such as

semiconductors.

The trouble with this

approach is that it prioritizes party control and state-owned enterprises over

China’s hard-working, innovative, and entrepreneurial private sector, primarily

responsible for its remarkable economic success over the last two decades. To

deal with a perceived external economic threat from Washington and an internal

political threat from private entrepreneurs whose long-term influence threatens

the power of the CCP, Xi faces a dilemma familiar to all authoritarian regimes:

how to tighten central political control without extinguishing business

confidence and dynamism.

Xi faces a similar

dilemma regarding what is perhaps his paramount goal: securing control over

Taiwan. Xi appears to have concluded that China and Taiwan are now further away

from peaceful reunification than at any time in the past 70 years. This is probably

correct. But China often ignores its own role in widening the gulf. Many of

those who believed that China would gradually liberalize its political system

as it opened up its economic system and became more connected with the rest of

the world also hoped that that process would eventually allow Taiwan to become

more comfortable with some form of reunification. Instead, China has become

more authoritarian under Xi. The promise of reunification under a “one country,

two systems” formula has evaporated as the Taiwanese look to Hong Kong. China

has imposed a harsh new national security law, arrested opposition politicians,

and restricted media freedom.

With peaceful

reunification off the table, Xi’s strategy now is clear: to vastly increase the

level of military power that China can exert in the Taiwan Strait, to the

extent that the United States would become unwilling to fight a battle that

Washington itself judged it would probably lose. Without U.S. backing, Xi

believes, Taiwan would either capitulate or fight on its own and lose. This

approach, however, radically underestimates three factors: the difficulty of

occupying an island that is the size of the Netherlands, has the terrain of

Norway, and boasts a well-armed population of 25 million; the irreparable

damage to China’s international political legitimacy that would arise from such

brutal use of military force; and the deep unpredictability of U.S. domestic

politics, which would determine the nature of the U.S. response if and when

such a crisis arose. In projecting its own deep strategic realism onto

Washington, Beijing has concluded that the United States would never fight a

war it could not win because to do so would be terminal for the future of

American power, prestige, and global standing. What China does not include in

this calculus is the reverse possibility: that the failure to fight for a

fellow democracy that the United States has supported for the entire postwar

period would also be catastrophic for Washington, particularly in terms of the

perception of U.S. allies in Asia, who might conclude that the American

security guarantees they have long relied on are worthless—and then seek their

own arrangements with China.

As for China’s

maritime and territorial claims in East China and South China Seas, Xi will not

concede an inch (and which creates difficulties for

some South-East Asian countries). This was recently illustrated by a

new law effective 1 February 2021 that allows

the Chinese coast guard to destroy any features established by its

neighbors on the sea’s rocks and shoals, to board and inspect any foreign

vessels within these waters, and to support Chinese claims to all the fish, all

gas, and other minerals within that vast area of sea. Thus China’s pretense of

any peaceful intent for its Coast Guard has been stripped away by Beijing’s

decision, effective now, to authorize this so-called coast guard to secure its

claim to the whole sea within its nine-dash line. This incorporates most of the

sea, which extends far to the south and east, close to its neighbor's shores,

to the coasts of Palawan and Borneo, Vietnam, and Indonesia’s Natuna Islands. China’s coast guard fleet exceeds the

combined total of such vessels owned by those countries which have struggled to

protect their waters and fishing rights against constant Chinese and sometimes

other incursions.

In turn, the USS John

McCain (below), a guided-missile destroyer, set a marker with the new

administration's first trip on February 4 through the 160-km. Strait separating

China and its renegade province, Taiwan.

China’s sweeping

claims of sovereignty over the sea, and the sea’s estimated 11 billion barrels

of untapped oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, have antagonized competing claimants Brunei,

Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. As early as the

1970s, countries began to claim islands and various zones in the South China Sea, such

as the Spratly Islands, which possess rich natural resources and fishing areas.

China maintains that, under international law, foreign

militaries are not able to conduct intelligence-gathering activities, such as

reconnaissance flights, in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). According to the

United States, claimant countries, under the UN Convention of the Law of the

Sea (UNCLOS), should have freedom of

navigation through

EEZs in the sea and are not required to notify claimants of military

activities. In July 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague

issued its ruling on a claim brought against China by the Philippines under

UNCLOS, ruling in favor of the Philippines on almost every count.

While China is a signatory to the treaty, which established the tribunal, it

refuses to accept the court’s authority.

In the meantime,

Beijing likely will seek to cast itself in as reasonable a light as possible in

its ongoing negotiations with Southeast Asian claimant states on the joint use

of energy resources and fisheries in the South China Sea. Here, as elsewhere, China

will fully deploy its economic leverage in the hope of securing the region’s

neutrality in the event of a military incident or crisis involving the United

States or its allies. In the East China Sea, China will continue to increase

its military pressure on Japan around the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands.

Still, as in Southeast Asia, here too, Beijing is unlikely to risk an armed

conflict, particularly given the unequivocal nature of the U.S. security

guarantee to Japan. However small, any risk of China losing such a conflict

would be politically unsustainable in Beijing and have massive domestic

political consequences for Xi.

Near-term risks and long-term strengths

As suggested

underneath all these strategic choices lies Xi’s belief, reflected in official

Chinese pronouncements and CCP literature, that the United States is

experiencing a steady, irreversible structural decline. This belief is now

grounded in a considerable body of evidence. A divided U.S. government failed

to craft a national strategy for long-term investment in infrastructure,

education, and basic scientific and technological research. The Trump

administration damaged U.S. alliances, abandoned trade liberalization, withdrew

the United States from its leadership of the postwar international order, and

crippled U.S. diplomatic capacity. Meanwhile, it remained unclear if McConnell

can shrink Trump's Republican Party (GOP) influence by

Trump and his allies. Thus the American political class and electorate are so

deeply polarized that it will prove difficult for any president to quickly win

support for a long-term bipartisan strategy on China. Washington, Xi believes,

is doubtful to recover its credibility and confidence as a regional and global

leader. And he is betting that as the next decade progresses, other world

leaders will come to share this view and begin to adjust their strategic postures

accordingly, gradually shifting from balancing with Washington against Beijing

or has been shown in

the case of Europe to hedging between the two powers to bandwagoning

with China.

But China worries

about the possibility of Washington lashing out at Beijing in the years before

U.S. power finally dissipates. Xi’s concern is not just a potential military

conflict but also any rapid and radical economic decoupling. Moreover, the

CCP’s diplomatic establishment fears that the Biden administration, realizing

that the United States will soon be unable to match Chinese power on its own,

might form an effective coalition of countries across the democratic capitalist

world with the express aim of counterbalancing China collectively. In

particular, CCP leaders fear that President Joe Biden’s

proposal to hold a summit of the world’s major democracies represents the

first step on that path, which is why China acted rapidly to secure new trade

and investment agreements in Asia and Europe before the new administration came

into office.

Considering this

combination of near-term risks and China’s long-term strengths, Xi’s general

diplomatic strategy toward the Biden administration will de-escalate immediate

tensions and stabilize the bilateral relationship as early as possible, and do

everything possible to prevent security crises. To this end, Beijing will look

to fully reopen the lines of high-level military communication with Washington

that were largely cut off during the Trump administration. Xi might seek to

convene a regular, high-level political dialogue, as well. However, Washington

will not be interested in reestablishing the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic

Dialogue, which served as the main channel between the two countries until its

collapse amid the trade war of 2018–19. Finally, Beijing may moderate its

military activity in the immediate period ahead in areas where the People’s

Liberation Army rubs up directly against U.S. forces, particularly in the South

China Sea and around Taiwan, assuming that the Biden administration discontinues

the high-level political visits to Taipei that became a defining feature of the

final year of the Trump administration. For Beijing, however, these are changes

in tactics, not in strategy.

As Xi tries to

ratchet down tensions in the near term, he will have to decide whether to

continue pursuing his hard-line strategy against

Australia, Canada, and India, which are friends or allies of the United States.

This has involved a combination of a deep diplomatic freeze and economic

coercion, and, in the case of India, direct

military confrontation. Xi will wait for any clear signal from Washington

that part of the price for stabilizing the U.S.-Chinese relationship would be

an end to such coercive measures against U.S. partners. If no such signal is

forthcoming, there was none under President Donald Trump, then Beijing will

resume business as usual.

Climate change

Meanwhile, Xi will

seek to work with Biden on

climate change. Xi understands this is in China’s interests because of its

increasing vulnerability to extreme weather events. He also realizes that Biden

has an opportunity to gain international prestige if Beijing cooperates with

Washington on climate change, given the weight of Biden’s own climate

commitments, and he knows that Biden will want to be able to demonstrate that

his engagement with Beijing led to reductions in Chinese carbon emissions. As

China sees it, these factors will deliver Xi some leverage in his overall

dealings with Biden. And Xi hopes that greater collaboration on climate will

help stabilize the U.S.-Chinese relationship more generally.

However, adjustments

in Chinese policy along these lines are still likely to be tactical rather than

strategic. Indeed, there has been remarkable continuity in Chinese strategy

toward the United States since Xi came to power in 2013. Beijing has been surprised

by the relatively limited degree to which Washington has pushed back, at least

until recently. Xi, driven by a sense of Marxist-Leninist determinism, also

believes that history is on his side. As Mao was before him, Xi has become a

formidable strategic competitor for the United States.

The balance of power made anew?

On 10 February, three

weeks after U.S. President Joe Biden took office, he had his first

phone call with Chinese President Xi Jinping. The call took place just

ahead of China’s Lunar New Year holiday, and the leaders apparently started

their conversations wishing each other well in the coming Year of the Ox.

According to the

White House readout, Biden underscored his fundamental concerns about

Beijing’s coercive and unfair economic practices, a crackdown in Hong Kong,

human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and increasingly assertive actions the region,

including toward Taiwan.

According to the Chinese

Foreign Ministry's

readout, Xi placed much more emphasis on the need to return to cooperation.

“You have said that America can be defined in one word: Possibilities.

According to the only direct quote from the readout, we hope the possibilities

will now point toward an improvement of China-U.S. relations,” Xi told Biden.

In all this, Biden

promises to remain tough on China, albeit without Trump's unpredictable and

publicly hostile diplomacy, but there is no sense of China backing down, even

in the face of sanctions and international opprobrium.

During the Trump

years, Beijing benefited not because of what it offered the world but because

of what Washington ceased to offer. The result was that China achieved

victories such as the massive Asia-Pacific free-trade deal known as the

Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the EU-China Comprehensive

Agreement on Investment, enmesh the Chinese European economies to a far greater

degree than Washington would like.

China is wary of the

Biden administration’s ability to help the United States recover from those

self-inflicted wounds. Beijing has seen Washington bounce back from political,

economic, and security disasters before. Nonetheless, the CCP remains confident

that the inherently divisive nature will make it impossible for the new

administration to solidify support for any coherent China strategy it might

devise.

So what difference will Biden make?

Biden intends to

prove Beijing wrong in its assessment that the United States is now in

irreversible decline. He will seek to use his extensive experience on Capitol

Hill to forge a domestic economic strategy to rebuild the foundations of U.S.

power in the post-pandemic world. He is also likely to continue to strengthen

the capabilities of the U.S. military and do what it takes to sustain American

global technological leadership. He has assembled a team of economic, foreign

policy, and national security advisers who are experienced professionals and

well versed in China, in stark contrast to their predecessors, who, with a

couple of midranking exceptions, had little grasp of China and even less grasp

of how to make Washington work. Biden’s advisers also understand that to

restore U.S. power abroad, they must rebuild the U.S. economy at home in ways

that will reduce the country’s staggering inequality and increase economic

opportunities for all Americans. Doing so will help Biden maintain the

political leverage he’ll need to craft a durable China strategy with bipartisan

support, no mean feat when opportunistic opponents such as Pompeo will have

ample incentive to disparage any plan he puts forward as little more than

appeasement.

To lend his strategy

credibility, Biden will have to make sure the U.S. military stays several steps

ahead of China’s increasingly sophisticated array of military capabilities.

This task will be made more difficult by intense budgetary constraints and pressure

from some factions within the Democratic Party to reduce military spending to

boost social welfare programs. For Biden’s strategy to be seen as credible in

Beijing, his administration will need to hold the line on the aggregate defense

budget and cover increased expenses in the Indo-Pacific region by redirecting

military resources away from less pressing theaters, such as Europe.

As China becomes

richer and stronger, the United States’ largest and closest allies will become

ever more crucial to Washington. For the first time in many decades, the United

States will soon require its allies' combined heft to maintain an overall balance

of power against an adversary. China will keep trying to peel countries away

from the United States, such as Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan,

South Korea, and the United Kingdom, using a combination of economic carrots

and sticks. To prevent China from succeeding, the Biden administration needs to

commit itself to fully opening the U.S. economy to its major strategic

partners. The United States prides itself on having one of the most open

economies in the world. But even before Trump’s pivot to protectionism, that

was not the case. Washington has long burdened even its closest allies with

formidable tariff and nontariff barriers to trade, investment, capital,

technology, and talent. If the United States wishes to remain the center of

what until recently was called “the free world,” then it must create a seamless

economy across the national boundaries of its major Asian, European, and North

American partners and allies. To do so, Biden must overcome the protectionist

impulses that Trump exploited and build support for new trade agreements

anchored in open markets. To allay the fears of a skeptical electorate, he will

need to show Americans that such agreements will ultimately lead to lower

prices, better wages, more opportunities for U.S. industry, and stronger

environmental protections and assure them that the gains won from trade

liberalization can help pay for major domestic improvements in education,

childcare, and health care.

The Biden administration

will also strive to restore the United States’ leadership in multilateral

institutions such as the UN, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund,

and the World Trade Organization. After four years of watching the Trump

administration sabotage much of the postwar international order machinery, most

of the world will welcome this. But the damage will not be repaired overnight.

The most pressing priorities are fixing the World Trade Organization’s broken

dispute-resolution process, rejoining the Paris agreement on climate change,

increasing the capitalization of both the World Bank and the International

Monetary Fund (to provide credible alternatives to China’s Asian Infrastructure

Investment Bank and its Belt and Road Initiative), and restoring U.S. funding

for critical UN agencies. Such institutions have not only been instruments

of U.S. soft power since Washington helped create them after the last world

war; their operations also materially affect American hard power in areas such

as nuclear proliferation and arms control. Unless Washington steps up to the

plate, the international system's institutions will increasingly become Chinese

satrapies, driven by Chinese finance, influence, and personnel.

Could a war be inevitable?

The deeply

conflicting nature of U.S. and Chinese strategic objectives and the profoundly

competitive nature of the relationship may conflict. As seen from the

above-mentioned poll devised by Adam NI, even war seems inevitable, even if

neither country wants that outcome. China will seek to achieve global economic

dominance and regional military superiority over the United States without

provoking direct conflict with Washington and its allies. Once it achieves

superiority, China will incrementally change its behavior toward other states,

especially when their policies conflict with China’s ever-changing definition

of its core national interests. On top of this, China has already sought to

gradually make the multilateral system more obliging of its national interests

and values.

But a gradual,

peaceful transition to an international order that accommodates Chinese

leadership now seems far less likely to occur than it did just a few years ago.

For all the eccentricities and flaws of the Trump administration, its decision

to declare China a strategic competitor, formally end the doctrine of strategic

engagement, and launch a trade war with Beijing succeeded in clarifying that

Washington was willing to put up a significant fight. And the Biden

administration’s plan to rebuild the fundamentals of national U.S. power at

home, rebuild U.S. alliances abroad, and reject a simplistic return to earlier

forms of strategic engagement with China signals that the contest will

continue, albeit tempered by cooperation in several defined areas.

The question for both

Washington and Beijing, then, is whether they can conduct this high level of

strategic competition within agreed-on parameters that would reduce the risk of

a crisis, conflict, and war. In theory, this is possible; in practice, however,

the near-complete erosion of trust between the two has radically increased the

degree of difficulty. Indeed, many in the U.S. national security community

believe that the CCP has never had any compunction about lying or hiding its

true intentions to deceive its adversaries. In this view, Chinese diplomacy

aims to tie opponents’ hands and buy time for Beijing’s military, security, and

intelligence machinery to achieve superiority and establish new facts on the

ground. To win broad support from U.S. foreign policy elites, therefore, any

concept of the managed strategic competition will need to include a stipulation

by both parties to base any new rules of the road on a reciprocal practice of

“trust but verify.”

The idea of managed

strategic competition is anchored in a deep realist view of the global order.

It accepts that states will continue to seek security by building a balance of

power in their favor while recognizing that in doing so, they are likely to create

security dilemmas for other states whose fundamental interests may be

disadvantaged by their actions. In this case, the trick is to reduce the risk

to both sides as the competition between them unfolds by jointly crafting a

limited number of rules of the road that will help prevent war. The rules will

enable each side to compete vigorously across all policy and regional domains.

But if either side breaches the rules, then all bets are off, and it’s back to

all the hazardous uncertainties of the law of the jungle.

The first step to

building such a framework would be to identify a few immediate steps that each

side must take for a substantive dialogue to proceed and a limited number of

hard limits that both sides (and U.S. allies) must respect. Both sides must

abstain, for example, from cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructure.

Washington must return to strictly adhering to the “one China” policy,

especially by ending the Trump administration’s provocative and unnecessary

high-level visits to Taipei. For its part, Beijing must dial back its

recent pattern of provocative military exercises, deployments, and maneuvers in

the Taiwan Strait. In the South China Sea, Beijing must not reclaim or

militarize any more islands and must commit to respecting freedom of navigation

and aircraft movement without challenge; for its part, the United States and

its allies could then (and only then) reduce the number of operations they

carry out in the sea. Similarly, China and Japan could cut back their military

deployments in the East China Sea by mutual agreement over time.

If both sides could

agree on those stipulations, each would have to accept that the other will

still maximize its advantages while stopping short of breaching the limits.

Washington and Beijing would continue to compete for strategic and economic

influence across the world's various regions. They would keep seeking

reciprocal access to each other’s markets and would still take retaliatory

measures when such access was denied. They would still compete in foreign

investment markets, technology markets, capital markets, and currency markets.

And they would likely carry out a global contest for hearts and minds, with

Washington stressing the importance of democracy, open economies, and human

rights and Beijing highlighting its approach to authoritarian

capitalism.

Even amid escalating

competition, however, there will be some room for cooperation in several

critical areas. This occurred even between the United States and the Soviet

Union at the height of the Cold War. It should certainly be possible between

the United States and China when the stakes are not nearly high. Besides

collaborating on climate change, the two countries could conduct bilateral

nuclear arms control negotiations, including the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban

Treaty's mutual ratification, and work toward an agreement on acceptable

military applications of artificial intelligence. They could cooperate on North

Korean nuclear disarmament and on preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear

weapons. They could undertake a series of confidence-building measures across

the Indo-Pacific region, such as coordinated disaster-response and humanitarian

missions. They could work together to improve global financial stability,

especially by agreeing to reschedule developing countries' debts hit hard by

the pandemic. And they could jointly build a better system for distributing

COVID-19 vaccines in the developing world.

That list is far from

exhaustive. But the strategic rationale for all the items is the same: it is

better for both countries to operate within a joint framework of managed

competition than to have no rules. The framework would need to be negotiated

between a designated and trusted high-level representative of Biden and a

Chinese counterpart close to Xi; only a direct, high-level channel of that sort

could lead to confidential understandings on the hard limits to be respected by

both sides. These two people would also become contact points when violations

occurred, as they are bound to, from time to time, and police the consequences

of any such violations. Over time, a minimum level of strategic trust might

emerge. And maybe both sides would also discover that the benefits of continued

collaboration on common planetary challenges, such as climate change, might

begin to affect the other, more competitive and even conflictual areas of the

relationship.

There will be many

who will criticize this approach as naive. Their responsibility, however, is to

come up with something better. Both the United States and China are currently

searching for a formula to manage their relationship for the dangerous decade

ahead. The hard truth is that no relationship can ever be managed unless there

is a basic agreement between the parties on that management's terms.

Game on?

What would be the

success measures should the United States and China agree on such a joint

strategic framework? One sign of success would be if, by 2030, they have

avoided a military crisis or conflict across the Taiwan Strait or a

debilitating cyberattack. A convention banning various forms of robotic warfare

would be a clear victory, as would the United States and China acting

immediately together, and with the World Health Organization, to combat the

next pandemic. Perhaps the most important sign of success, however, would be a

situation in which both countries competed in an open and vigorous campaign for

global support for the ideas, values, and problem-solving approaches that their

respective systems offer, with the outcome still to be determined.

Success, of course,

has a thousand fathers, but failure is an orphan. But the most demonstrable

example of a failed approach to managed strategic competition would be over

Taiwan. If Xi were to calculate that he could call Washington’s bluff by

unilaterally breaking out of whatever agreement had been privately reached with

Washington, the world would find itself in a world of pain. In one fell swoop,

such a crisis would rewrite the future of the global order.

For updates click homepage here