Eric Vandenbroeck

30 Jan. 2020

First of all, from

what we know today it is likely that the virus will indeed become a pandemic whereby

public health services can help determine how severe it will turn out to be.

Our evaluation of any

infectious disease is based on two factors: How fast and easily it transmits,

and how serious it is. At the moment the 2019-nCoV coronavirus outbreak so far

is not as lethal as either SARS or the currently simmering Middle East

Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) on the Arabian Peninsula. Yet this variant is

packing a vicious punch and unlike SARS or MERS, is spreading far and wide,

acting like an influenza virus in terms of transmission between people, quickly

and efficiently traveling through the air. Viruses don’t change when crossing

political borders, so we can expect this one to continue behaving as they did

in China. Nothing any government can do will effectively stop its spread.

World Health

Organization officials said Thursday (30 Jan.) morning in China that the coronavirus

death toll has climbed to 170, and more than 7,700 cases have been reported

worldwide.

And whilst as

mentioned above early indications so far show it is not as deadly as SARS, the

coronavirus that emerged in China in 2002, it’s

spread has certainly matched the growth of the SARS outbreak.

The reason why the

new infectious disease is so alarming is as tens of cases become hundreds and

hundreds become thousands, the mathematics run away with you, conjuring

speculation about a health-care collapse, social and economic upheaval, and a

deadly pandemic. The other is profound uncertainty. Sparse data and conflicting

reports mean that scientists cannot rule out the worst case, and that lets

wrong information thrive.

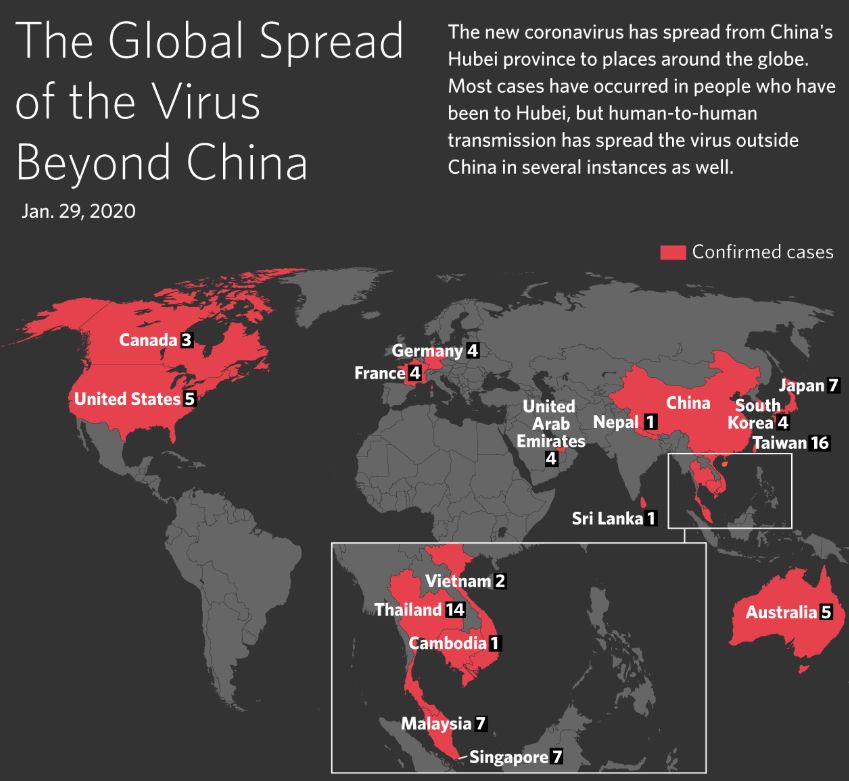

So far, we know the

disease has taken hold in China and there is a high risk that it spreads around

the world; it may even become a recurrent seasonal infection. It may turn out

to be no more lethal than seasonal influenza, but that would still count as

dangerous in the short term that would hit the world economy and, depending on

how the outbreak is handled, it could, as we will see underneath, also have

political effects in china.

The most significant

uncertainty is how many cases have gone unrecorded. Modeling by academics in Hong Kong suggests

that tens of thousands of people have already been infected and that

the epidemic will peak in a few months’ time. if so, the virus is more

widespread than thought, and hence will be harder to contain, but it will also

prove less lethal, because the number of deaths should be measured against a

much broader base of infections. As with the flu, a lot of people could die

nonetheless.

Scientists have

started work on vaccines and on treatments to make infections less severe,

but these are six to 12 months away, so the world must fall back on

public-health measures. in china that has led to the

biggest quarantine in history, as Wuhan and the rest of Hubei province have

been sealed off. the impact of such draconian measures has rippled throughout china. the spring holiday has been extended, keeping

schools and businesses closed. the economy is running on the home-delivery of

food and goods.

Many experts praise china’s efforts. Certainly, its scientists have coped

better with the Wuhan virus than they did with Sar's in 2003, rapidly detecting

it, sequencing its genome, licensing diagnostic kits, and informing

international bodies. China’s politicians come off less well. They left alone

the crowded markets filled with wild animals that spawned Sar's. With the new

virus, local officials in Wuhan first played down the science and then, when

the disease had taken hold, enacted the draconian quarantine fully eight hours

after announcing it, allowing perhaps 1m potentially infectious people to leave

the city first.

That may have

undermined a measure which is taking a substantial toll. China’s growth in the

first quarter could fall to as little as 2%, from 6% before the outbreak. As

China accounts for almost a fifth of world output, there will probably be a

noticeable dent on global growth. Though the economy will bounce back when the

virus fades, the reputation of the communist party and even of Xi Jinping may

be more lastingly affected. The party claims that armed with science, it is

more efficient at governing than democracies. The heavy-handed failure to

contain the virus suggests otherwise.

The “people’s leader”

If censors in

communist-led regimes are good for anything, it is spurring creativity. With a

new coronavirus stalking china, netizens have been

heaping praise on “Chernobyl”, an American-made television drama about the

soviet union’s worst nuclear disaster. Their aim is to sneak discussion of the

outbreak onto china’s tightly policed internet. In

less hectic times, censors would swiftly stamp out such impertinence. For the

parallels with the reactor explosion in 1986, and the official cover-up that

followed, are painful for china’s communist party

bosses, whose system of government was cribbed from soviet designs. But pointed

comparisons keep popping up on china’s social media.

One urges Chinese viewers to learn from “Chernobyl” that a free flow of

information offers more security than aircraft-carriers, moon landings, and

other signs of superpower might. Another contrasts a soothing interview granted

to state television by the governor of Hubei, the province where the epidemic

began, with a speech by the hero of “Chernobyl”, a soviet scientist, about the

costs of official lies.

Parallels are likely

to continue in the real world. Back in the 1980s, kremlin leaders scapegoated

local officials and engineers, coolly blaming them for the disaster and denying

a more extensive cover-up. In recent days, Chinese state media have dropped

heavy hints that the mayor of Wuhan, the industrial city where the virus was first

detected, will lose his job. When Li Keqiang, china’s

prime minister, was appointed to oversee virus-control work, cynics suggested

that his role was to take the fall should the outbreak spark a pandemic, in

effect, to protect the president xi Jinping.

As it happens,

censors should be relieved that Chinese netizens are focusing on the ills of

soviet collective leadership. it would be more dangerous if online critics were

to start exploring a historical parallel closer to home, namely the way that in

Chinese history natural disasters undermined an emperor’s claim to rule. More

than one dynasty fell after catastrophes signaled that heaven had withdrawn its

favor. It was not only seen as ineptitude when a ruler was unable to protect

his people from floods or famine, or, as in the second century during the Han

dynasty, from repeated outbreaks of disease (probably smallpox and measles)

that killed perhaps a third of the population. Such bungling showed that the

emperor lacked virtue and deserved to be overthrown, people said.

Modern-day Chinese

may not believe that a rampaging coronavirus signals divine anger with Xi.

still, the party chief has a great deal at stake in this crisis, precisely

because broad claims are made about his wisdom, which is now taught in schools

and studied by party members as xi Jinping thought. Every day, state media

credit Xi with personally guiding china to

ever-greater prosperity, modernity, and global clout. No leader has amassed

such individual power since Mao Zedong or been so lavishly praised. Chinese

intellectuals accuse Xi of claiming the mantle of an emperor. They point to

xi’s speeches praising traditional Asian culture and lauding codes of morality

and deference to imperial authority, as handed down by Confucius and other sages.

The result is an

awkward hybrid. On the one hand, officials make claims about the efficiency of

collective party leadership that would be familiar to any soviet apparatchik.

To them, populist insurgencies sweeping the west are proof that multiparty

elections, a free press, and other forms of democratic accountability are

sources of chaos and dysfunction. As they describe it, china’s

system is a meritocracy that selects highly competent experts to run the

country, with a track record of correcting their own mistakes. Yet at the same

time, the party’s propagandists lay claim to a very different form of

legitimacy, involving the people’s love for and trust in one man, xi. so

sweeping is their praise of him that it leaves essentially no room for the idea

that xi could make a serious mistake.

This convoluted claim

to legitimacy can be heard in the context of the current coronavirus outbreak,

as leaders insist that their system of government is ideally suited to tackling

the disease. On 28 January Chinese

leaders hosted

the head of the world health organization (who), a un body that played an invaluable

role in demanding transparency in 2003 after china’s

initial cover-up of the extent of an outbreak of severe acute respiratory

syndrome (sars), which led to many avoidable deaths.

Wang Yi, the foreign minister, assured the who’s boss Tedros Adhanom

Ghebreyesus that china would be more resolute this

time thanks to “the

strong leadership of the party central committee with comrade xi jinping as the core and the strong advantages of the

socialist system”, as well as its experience of sars.

It is too simplistic

to assume that all bad things that happen in china

must harm xi. the virus outbreak could end swiftly, amid worldwide praise for

the bravery of china’s doctors and nurses, the

self-discipline of the public, and the resolve of Chinese leaders, albeit after

a slow start. If the crisis does not end well, scapegoats will be found, and

underlings punished. That alone would not have to shake xi’s authority, which

can always be shored up with repression, still greater ideological discipline,

and nationalist propaganda. But a botched response to the virus would lay bare

tensions inherent in the party’s hybrid claims to legitimacy.

Xi’s china is two things at once. It is a secretive, techno-authoritarian

one-party state, ruled by grey men in unaccountable councils and secretive

committees. It also claims to be a nation-sized family headed by a patriarch of

unique wisdom and virtue, in a secular, 21st-century version of the mandate of heaven.

If forced to choose between those competing models, bet on cold, bureaucratic

control to win out. For Xi and his team learned their lesson from the soviet

union’s fall, five years after the Chernobyl disaster. Expressions of public

love for Xi, the “people’s leader,” are all very well. But keeping power is

what counts.

Chinese abroad unfairly countered with the

"yellow peril" narrative

In the past two days,

the hashtag #jenesuispasunvirus, "I am not a virus" in French,

trended on Twitter as thousands of ethnically Asian internet users spoke out against

the surge in discrimination.

Airlines halt flights

from China. Schools in Europe uninvite exchange students. Restaurants in South

Korea turn away Chinese customers.

As a deadly virus spreads

beyond China, governments, businesses and educational institutions are

struggling to find the right response. Safeguarding public health is a

priority. How to do that without stigmatizing the entire population of the

country where the outbreak began, and where nearly a fifth of all humans

reside, is a challenge. French regional newspaper Courrier

Picard sparked outrage with its headline "Yellow Alert" on a

front-page story about the coronavirus. The paper apologized to readers who

took to Twitter to condemn the allusion to "Yellow Peril," a

xenophobic term referring to the peoples of East Asia that dates to the 19th

century. In Denmark, the Chinese Embassy called on the country's

Jyllands-Posten newspaper to apologize for an editorial cartoon that depicts

China's flag with virus symbols instead of stars on a red background.

Disinformation spread

When reports of a new

coronavirus emerged within a week or so a theory would be circulating that

coronavirus was a new kind of “snake

flu”– mostly because it’s unlikely the virus originated in snakes, and it’s

not flu.

So where did the

snakes come from? The culprit was a widely shared

scientific paper, which speculated that the new virus had genetic

characteristics and implicated snakes as the source. Leading geneticists were

quick to point out that the results weren’t convincing, and that bats were

still the likely suspects. However, that didn’t stop snake flu from going

viral. Other misinformation about coronavirus has rippled across the internet

in recent weeks. From claims the virus is part-HIV

to conspiracy

theories about bioweapons and reports suggesting the virus was linked to

people eating bat

soup, stories sparking fear seem to have overtaken the outbreak in real

life.

To fully explain how

viral content – and viruses – spread, we need to move away from the idea that

outbreaks involve simple clockwork infections, passing along a chain from

person to person to person until large numbers have been exposed. During the

2015 outbreak of the Mers coronavirus in South Korea, 82 out of 186

infections came from a single “superspreading event” in a hospital where an

infected person was being treated. It’s not yet clear how common such

superspreading is in the current outbreak, but we do know that these kinds of

events are how information goes viral online; most outbreaks on Twitter are

dominated by a handful of individuals or media outlets, which are responsible

for a large proportion of transmission. If you heard about snake flu, you might

have told a couple of friends; meanwhile, newspaper headlines were telling

millions.

Ensuring the public

has the best possible health information is crucial during an outbreak. At

best, misinformation can distract from important messages. At worst, it can

lead to behaviour that amplifies disease

transmission. The novelty of coronavirus makes the challenge even greater,

because viral speculation can easily overwhelm the limited information we do

have.

Not to mention that

while it might soon reach the capital cities of all 'regions' there are many

'places' in China's rural areas where the coronavirus will not reach...

Linguistic diversity in the various

regions of China:

For updates click homepage here