While stock markets

are sliding as forecasters have cut their estimates of economic growth around the

world, the more important question is how governments can best deal with the

pandemic, confirming what I was suggesting as

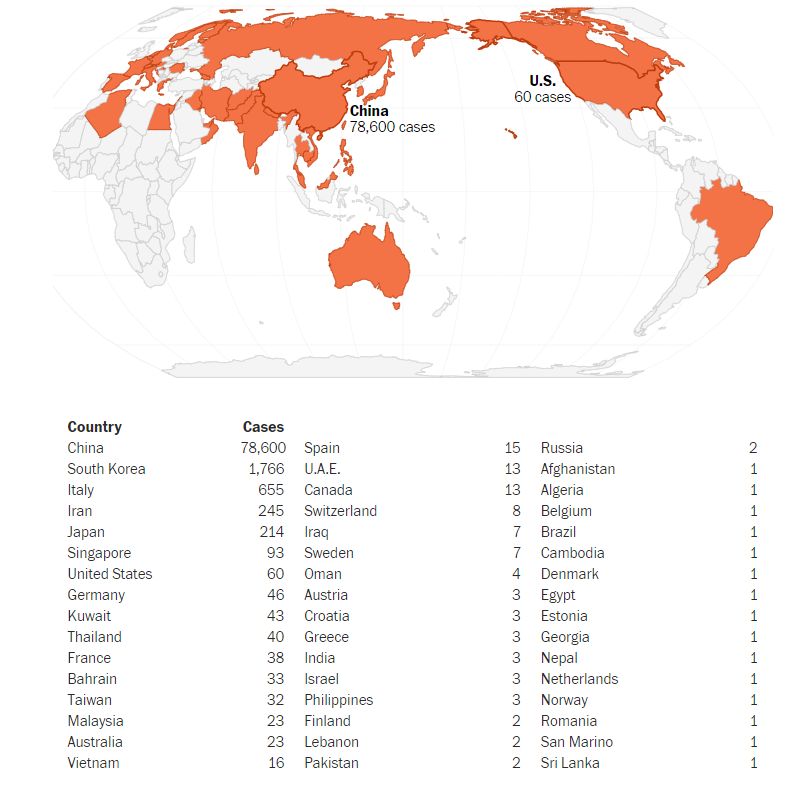

early as 30 Jan. the viruses now already have been found in at least 56

countries as case numbers outside China rise fast. Also coronavirus infections

among Iran’s senior leaders are raising questions over the extent of an

outbreak that has become a flashpoint in the worldwide spread of the virus.

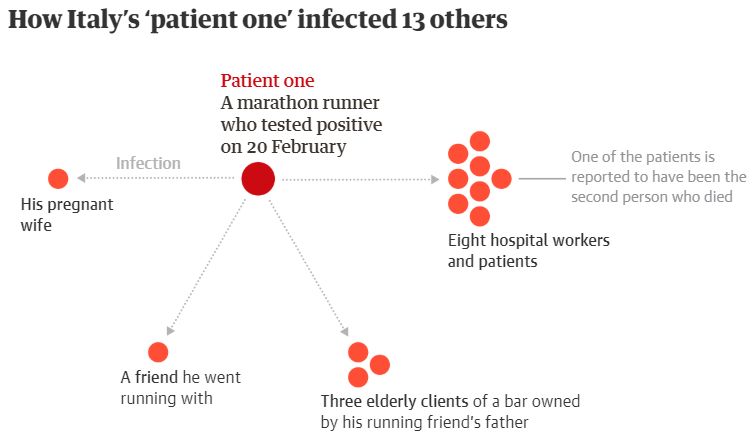

Also on 21 February,

the Italian authorities announced that a cluster of 16 cases of covid-19, had

been detected

around Codogno, a small town in Lombardy 60km south-east of Milan. By the

next day, the number was up to 60, and five older adults had died. On the 23rd,

“red zones” were set up around the infected areas. Inside the zones, there is a

strict lockdown; outside 500 police officers and soldiers stop people from

leaving. On the same day, the government of Lombardy ordered the closure of any

establishment where large numbers of people gather, including cinemas, schools,

and universities.

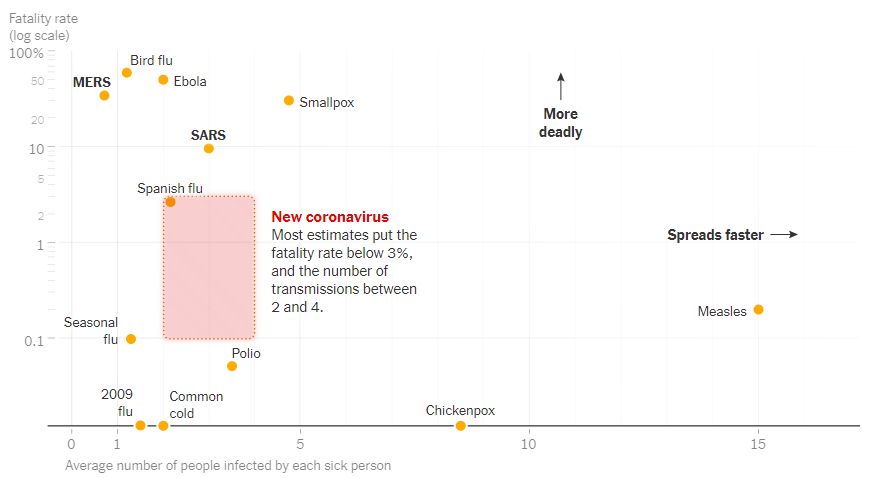

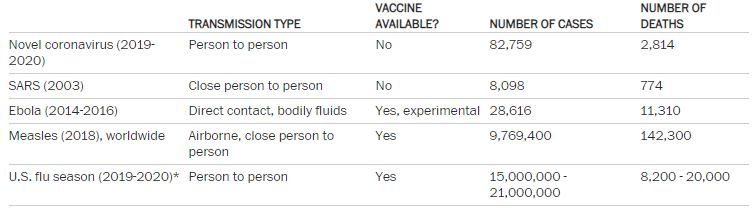

Thus officials

worldwide will have to act when they do not have all the facts because much

about the virus is unknown. A broad guess is that 25-70% of the population of

an infected country may catch the disease. China’s experience suggests that, of

the cases that are detected, roughly 80% will be mild, 15% will need treatment

in hospital, and 5% will require intensive care. Experts say that the virus was

maybe five to ten times as lethal as seasonal flu, which, with a fatality rate

of 0.1%, kills 60,000 Americans in a bad year. Across the world, the death toll

could be in the millions.

A 1918 pandemic circled

the world three times over two years, infecting a third of the population and

killing at least 50 million, and that was before globalization, and widespread

international travel. The fact that it is still being talked about over a

century later gives a measure of both the gravity of the outbreak, and the

potential threat we are currently facing.

For years the public

health community has been saying two important things in this respect: One,

that it was only a matter of time before a serious pandemic hit again; and two,

that the global health systems were woefully

unprepared to tackle the emergency.

If the pandemic is

like a very severe flu, models point to global economic growth being two

percentage points lower over 12 months, at around 1%; if it is worse still, the

world economy could shrink. As that prospect sank in during the week, the USA S&P

500 so far fell by close to 8% and is likely to drop much more.

Yet all those

outcomes depend significantly on what governments choose to do, as China shows.

Hubei province, the origin of the epidemic, has a population of 59m. It has

seen more than 65,000 cases and a fatality rate of 2.9%. By contrast, the rest

of China, which contains 1.3bn people, has suffered fewer than 13,000 cases

with a fatality rate of just 0.4%. Chinese officials at first suppressed news

of the disease, a grave error that allowed the virus to take hold. But even

before it had spread much outside Hubei, they imposed the largest and most

draconian quarantine in history. Factories shut, public transport stopped, and

people were ordered indoors. This raised awareness and changed behavior.

Without it, China would, by now, have registered many millions of cases and

tens of thousands of deaths.

The World Health

Organization was this week full of praise for China’s approach. That does not,

however, mean it is a model for the rest of the world. All quarantines carry a

cost, not just in lost output, but also in the suffering of those locked away, some

of whom forgo medical treatment for other conditions. It is still too soon to

tell whether this price was worth the gains. As China seeks to revive its

economy by relaxing the quarantine, it could well be hit by a second wave of

infections. Given that uncertainty, few democracies would be willing to trample

over individuals to the extent China has. And, as the chaotic epidemic in Iran

shows, not all authoritarian governments are capable of it.

Yet even if many

countries could not, or should not, exactly copy China, its experience holds

three essential lessons, to talk to the public, to slow the transmission of the

disease, and to prepare health systems for a spike in demand.

A good example of

communication in America’s Centers for Disease Control, which issued a clear,

unambiguous warning on February 25th. A bad one is Iran’s deputy health

minister, who succumbed to the virus during a press conference designed to show

that the government is on top of the epidemic.

Even well-meaning

attempts to sugarcoat the truth are self-defeating because they spread

mistrust, rumors, and, ultimately, fear. The signal that the disease must be

stopped at any cost, or that it is too terrifying to talk about, frustrates

efforts to prepare for the virus’s inevitable arrival. As governments dither,

conspiracy theories coming out of Russia are already sowing doubt, perhaps to

hinder and discredit the response of democracies.

The best time to

inform people about the disease is before the epidemic. One message is that

fatality is correlated with age. If you are over 80 or you have an underlying

condition, you are at high risk; if you are under 50, you are not. Now is the

moment to persuade the future 80% of mild cases to stay at home and not rush to

a hospital. People need to learn to wash their hands often and to avoid

touching their face. Businesses need continuity plans to let staff work from

home and to ensure a stand-in can replace a vital employee who is ill or caring

for a child or parent. The model is Singapore, which learned from SARS, another

coronavirus, that clear, early communication limits panic.

China’s second lesson

is that governments can slow the spread of the disease. Flattening the spike of

the epidemic means that health systems are less overwhelmed, which saves lives.

If like flu, the virus turns out to be seasonal, some cases could be delayed

until next winter, by which time doctors will understand better how to cope

with it. By then, new vaccines and antiviral drugs may be available.

When countries have

few cases, they can follow each one, tracing contacts and isolating them. But

when the disease is spreading in the community, that becomes futile.

Governments need to prepare for the moment when they will switch to social

distancing, which may include canceling public events, closing schools,

staggering work hours, and so on. Given the uncertainties, governments will

have to choose how draconian they want to be. They should be guided by science.

International travel bans look decisive, but they offer little protection

because people find ways to move. They also signal that the problem is “them”

infecting “us,” rather than limiting infections among “us.” Likewise, if the

disease has spread widely, as in Italy and South Korea, “Wuhan-lite”

quarantines of whole towns offer scant protection at a high cost.

The third lesson is

to prepare health systems for what is to come. That entails careful logistical

planning. Hospitals need supplies of gowns, masks, gloves, oxygen, and drugs.

They should already be conserving them. They will run short of equipment, including

ventilators. They need a scheme for how to set aside wards and floors for

covid-19 patients, for how to cope if staff fall ill, and for how to choose

between patients if they are overwhelmed. By now, this work should have been

done.

This virus has

already exposed the strengths and weaknesses of China’s authoritarianism. It

will test all the political systems with which it comes into contact, in both

rich and developing countries. China has bought governments time to prepare for

a pandemic. They should use it.

For updates click homepage here