In February, the

coronavirus pandemic struck the world economy with the biggest shock since the second

world war. Lockdowns and a slump in consumer spending led to a labor-market

implosion in which the equivalent of nearly 500m full-time jobs disappeared

almost overnight. World trade shuddered as factories shut down, and countries

closed their borders. An even deeper economic catastrophe was avoided thanks

only to unprecedented interventions in financial markets by central banks,

government aid to workers and failing firms, and the expansion of budget

deficits to near-wartime levels.

The crash was

synchronized. As recovery takes place, however, huge gaps between countries'

performance are opening up, which could yet recast the world’s economic order.

According to forecasts by the OECD, America’s economy will be the same size by

the end of next year as it was in 2019, but China’s will be 10% larger. Europe

will still languish beneath its pre-pandemic level of output and could do so

for several years, a fate it may share with Japan, suffering from a demographic

squeeze. It is not just the biggest economic blocs that are growing at

different speeds. According to UBS, a bank, the distribution of growth rates

across 50 economies was at its widest for at least 40 years in the second

quarter of this year.

The variation is the

result of differences between countries. Most important is the spread of the

disease. China has all but stopped it while Europe, and perhaps soon America,

is battling a costly second wave. Over the past week, Paris has closed its bars,

and Madrid has gone into partial lockdown. In China, meanwhile, you can now

down sambuca shots in nightclubs. Another difference is the pre-existing

structure of economies. It is far easier to operate factories under social

distancing than running service-sector businesses that rely on face-to-face

contact. Manufacturing makes up a bigger share of the economy in China than in

any other big country. A third factor is the policy response. This is partly

about size: America has injected more stimulus than Europe, including spending

worth 12% of GDP and a 1.5 percentage point cut in short-term interest rates.

But the policy also includes how governments respond to the structural changes

and creative destruction the pandemic is causing.

As our special

report, this week explains, these adjustments will be immense. The pandemic

will leave economies less globalized, more digitized, and less equal. As they

cut risks in their supply chains and harness automation, manufacturers will

bring production closer to home. As office workers continue to work in their

kitchens and bedrooms for at least part of the week, lower-paid workers who

previously toiled as waiters, cleaners, and sales assistants will need to find

new jobs in the suburbs. Until they do, they could face long spells of

unemployment. In America, permanent job losses are mounting even as the

headline unemployment rate falls (see article).

As more activity

moves online, the business will become more dominated by firms with the most

advanced intellectual property and the biggest repositories of data; this

year’s boom in technology stocks gives a sense of what is coming, as does the

digital surge in the banking industry (see our leader on Ant Group). And low

real interest rates will keep asset prices high even if economies remain weak.

This will widen the gulf between Wall Street and Main Street that emerged after

the global financial crisis, worsening this year. The challenge for democratic

governments will be to adapt to all these changes while maintaining popular

consent for their policies and free markets.

That is not a concern

for China, which so far seems to be emerging from the pandemic strongest—at

least in the short run. Its economy has bounced back quickly. Later this month,

its leaders will agree on a new five-year plan, emphasizing Xi Jinping’s model

of high-tech state capitalism and increasing self-sufficiency. Yet the virus

has exposed longer-term flaws in China’s economic apparatus. It has no safety

net worth the name, and this year, it had to focus its stimulus on firms and

infrastructure investment rather than shoring up household incomes. And in the

long run, its surveillance and state control system, which made brutal

lockdowns possible, is likely to impede the diffuse decision-making and free

movement of people and ideas that sustain innovation and raise living

standards.

Europe is the

laggard. Its response to the pandemic risks ossifying economies there, rather

than letting them adjust. In its five biggest economies, 5% of the labor force

remains on short-work schemes in which the government pays them to await the

return of jobs or hours that may never come back (see article). In Britain, the

proportion is twice as high. Across the continent, suspended bankruptcy rules,

tacit forbearance by banks, and a flood of discretionary state aid risk

prolonging zombie firms' lives that should be allowed to fail. This is all the

more worrying given that, before the crisis, France and Germany were already

embracing an industrial policy that promoted national champions. If Europe sees

the pandemic as a further reason to nurture a cozy relationship between

government and incumbent businesses, its long-term relative decline could

accelerate.

The question-mark is

America. For much of the year, it got the policy balance roughly right. It

provided a more generous safety-net for the jobless and a larger stimulus than

might have been expected in the home of capitalism. Wisely, it also allowed the

labor market to adjust and has shown less inclination than Europe to bail out

firms in danger of becoming obsolete as the economy adjusts. Partly as a

result, unlike Europe, America already sees the creation of many new jobs.

Instead, America’s

weakness is toxic and divided politics. This week President Donald Trump seemed

to ditch talks over renewing its stimulus, meaning that the economy could fall

over a fiscal cliff. Whether to redesign the safety net for a tech-driven economy

or to put deficits on a sustainable course, critical reforms are all but

impossible. At the same time, two warring tribes define compromise as weakness.

Covid-19 is imposing a new economic reality. Every country will be called on to

adapt, but America faces a daunting task. If it is to lead the post-pandemic

world, it will have to reset its politics.

The Pandemic has hit

the world economy with the biggest shock since the second world war. It has

also created big

performance disparities between countries. According to forecasts by the

OECD, America’s economy will be the same size by the end of next year as it was

in 2019, but China’s will be 10% larger. The pandemic will also leave economies

less

globalized, more digitized, and less equal. It is accentuating global trade

imbalances. Its legacies will include even

lower interest rates and even higher asset prices. As the better-off work

on in their kitchens, lower-paid workers may face long spells of unemployment.

In America, permanent

job losses are mounting even as the headline unemployment rate falls, yet

there is a once-in-a-generation surge

in startups. And some existing businesses are booming. Despite a slowdown

in global trade, for example, the

shipping industry is having a banner year.

Another industry

enjoying a COVID-19 bonanza is digital

finance. A new era is dawning: conventional banks now account for only 72%

of the global banking and payments industry's total market value, down from 81%

at the start of the year and 96% a decade ago. Leading the charge against them

globally is Ant

Group, which began life as a payments service on Alibaba, a Chinese

e-commerce giant, but is about to sell shares in the biggest initial public

offering in history, which could value the company at over $300bn, more than

any bank in the world. Ant’s rise worries hawks in the White House and enthralls

global investors. It portends a bigger transformation of how the financial

system works, not just in China but around the world.

Sweden

has become a much-cited example in the debate about how to deal with COVID-19.

Held up as a champion of liberty, it is, in fact, the home

of pragmatism. So its policy is hardly one of the COVID

defiance displayed by President Donald Trump. Nor does Trump’s injunction

not to let the virus dominate people’s lives offer much consolation to the

world’s poor, suffering its consequences. In Latin

America, for example, years of progress in reducing poverty and inequality are

being wiped out. Everywhere, the hope is a vaccine will be available soon. Britain

is already making preparations to inoculate 30m people. Countries differ in

their views of who

should get access to a vaccine first. However, until one arrives, people in

rich countries are getting used to facing up to a

subject many had learned to put to one side: death.

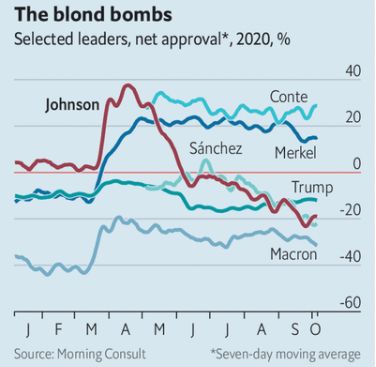

The pandemic is also

damaging perceptions of governments and national leaders, perhaps nowhere more

than in Britain.

In a survey by YouGov, a pollster, of how citizens of 22 countries think their

government has managed the pandemic, Britain bumps along at or near the bottom.

The ratings of the prime minister, Boris Johnson, have plunged in consequence.

Similarly, in Israel,

in indefinite nationwide lockdown, approval of Binyamin Netanyahu, the prime

minister, has handled the pandemic has slumped in polls from 58% in April to

just 27%. It will be scant consolation to the leaders concerned to know that it

is a worldwide trend for people to lose

trust in their governments as citizens gain access to the internet.

The historian Henry

Adams once noted that politics is about the systematic organization of hatreds.

Voters who have lost their jobs, have seen their businesses close, and have

depleted their savings are angry. There is no guarantee that this anger will be

channeled in a productive direction by the current political class, or by the

ones to follow if the politicians in power are voted out. A tide of populist nationalism

often rises when the economy ebbs, so mistrust among the global community

is almost sure to increase. This will speed the decline of multilateralism and

may create a vicious cycle by further lowering future economic prospects. That

is precisely what happened in between the two world wars, when nationalism and

beggar-thy-neighbor policies flourished.

There is no

one-size-fits-all solution to these political and social problems. But one

prudent course of action is to prevent the economic conditions that produced

these pressures from worsening. Officials need to press on with fiscal and

monetary stimulus. And above all, they must refrain from confusing a rebound

for a recovery.

For updates click homepage here