Worldly visions of

living outside empires, states, and nations had, from earlier times, carried

dark associations: with the quest for illicit knowledge like alchemy; with cabalistic brotherhoods;

of universal tongues written in cipher; freemasonry of the mind that was

constantly stigmatized by charges of disloyalty to the established order.1The

‘Cosmopolis’ was a commonplace of publication by the underground printers of

the Enlightenment, and ‘Cosmopolite’ a common pseudonym for radical writers. It

signified the clandestine world of the dispossessed, belonging nowhere.2 In the

late nineteenth century, the principal heirs to this tradition were the

anarchists. They were a central presence in Paris's émigré politics, and London

became their principal city of refuge. They were the first to withdraw from the

International after their leading thinker, the Russian Mikhail Bakunin, broke

with Marx and the International Workingmen’s Association in 1872, in the face

of what he saw as authoritarian tendencies. Anarchism’s ‘black internationals’

were, by the movement’s very nature, institutionally formless. No Asians

attended or were invited to their few congresses, the last of which was in

Amsterdam in 1907.3

But, denied full

access to the West's internationalism, Asian travelers created their own, to

which anarchist ideas seemed to speak directly.

Anarchism was mostly encountered through a broad spectrum of thought, as a path

rather than a doctrine, and – for its followers – as the antithesis of creed or

dogma. The most read and translated theorist in Asia, Peter Kropotkin, defined

anarchism in 1881 as a collective of individual acts. It offered a spectrum of

different economic and social organization approaches, such as mutualism,

federalism, syndicalism, and communism. In common with the times, most

anarchists tended to identify with scientific advance and expand the worldly

vision.4 The most comprehensive anarchist account of the world was the

nineteen-volume Nouvelle Géographie Universelle: La Terre et les Hommes (1876–94) of Elisée Reclus. His thought was distinctive in how it

‘provincialized’ Europe as humanity’s ‘smallest tribe’ and firmly set an

anarchist vision of the future within a global context.5 His writings also

anticipated the form and scale of the new urban spaces emerging in Asia. For

Reclus, the city was the highest form of communal life, a ‘collective

personality’ formed by mutually supporting, contrasting neighborhoods.6

Reclus’s writings

profoundly impacted Chinese studying in Paris, such as Li Shizeng,

who translated some of them and adopted them as a work-study foundation. The

Chinese-language journal this group founded in 1907, New Era (Xin Shiji), lasted three years and a hundred issues, generating

translations of anarchist thought that would circulate across Asia for many

years to come. Its banner-head carried an Esperanto subtitle, La Novaj Tempoji.7 Leo Tolstoy’s spiritual anarchism also

found followers among pacifists and socialists in Japan and China during the

Russo-Japanese War. In the face of the futility and doubts raised by early

confrontations with the colonial power, anarchism spoke directly to the

question of violence as a form of political struggle. And these and other

issues of theory – on the forms of a future society, on attitudes to the

‘nation’ – were increasingly worked through in struggles beyond Europe.8

During the French

Revolution, François-Noël Babeuf, who used

masonic forms and whose writings foreshadowed much later anarchist

thought, had argued that in the face of an oppressive, immovable state, ‘when a

nation takes the path of revolution it does so because the … masses realize

that their situation is intolerable, they feel impelled to change it, and they

are drawn into motion for that end’.9 By challenging the state’s monopoly of

violence, ‘terror’ could acquire meaning and purpose. After the violent

suppression of the Paris Commune of 1871 – in which not only anarchists fought

– the argument gained currency that terror could be discriminate, proportionate

even when it was self-defense in the face of police action. Such thinking

underlaid a decade of anarchist attentats in Europe and beyond.10 By a

different route, the populist Narodnik tradition in Russia that culminated in

the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in March 1881 struck an emotional chord

in India, Japan, and elsewhere. Others defended the motive for the deed, if not

the deed itself. But beyond Europe, in the United States, the anarchist, and

feminist theorist Emma Goldman, together with Alexander Berkman – about attacks

such as that on the Carnegie Steel Corporation boss Henry Clay Frick in

downtown Pittsburgh in July 1892 – argued that capitalists must take responsibility

for their actions. The question was, whom and what was to be targeted? What was

the threshold of guilt or innocence?

The invention of

dynamite, both as a weapon and as an idea, supported the arguments of men such

as Émile Henry, the infamous perpetrator of a series of fatal bomb attacks in

Paris in 1892–4, that the police’s indiscriminate targeting of anarchists

dictated an indiscriminate response. But despite the secret circulation of

manuals for bomb-making, the construction of explosive devices was a

specialized and hazardous affair. Most assassinations were a coup de main, and

many attempts failed. They were often the work of solitary, troubled figures,

dismissed as misanthropes. By the 1890s, despite the wave of violence that

killed eleven people in France between 1892 and 1894, extreme nihilism had been

largely disavowed in Europe. But although the 1892–4 attacks were unconnected,

the idea of a vast underlying conspiracy distilled many of the anxieties of a

global age and could not be dispelled. The state response conflated in the

popular mind the image of ‘the terrorist’ and ‘the anarchist,’ who were not at

all the same thing.11

What also traveled

was the figure of the terrorist as a modern demon, both as a theoretical ideal

and as a literary type. The agitator's aesthetic was usually that of a male,

monkish ascetic, ‘everything in him,’ as a much-traveled primer by Mikhail Bakunin

put it, ‘absorbed in a sole exclusive interest – in one thought – the

revolution.’ For initiates, this forged a sense of solidarity and heroic

martyrdom. In opponents' eyes, the anarchist was more of an individualist, an

egoist, often an aristocratic type, or a student alienated and alone.

Representations shaped reality: ‘the propaganda of the deed’ demanded that an

act be staged and publicized for maximum notoriety. Its effect lay as much in

the anticipation as in the bomb or the bullet itself: the dread that they could

puncture time and order at any moment and without forewarning. Fictional

representations of the deed, such as Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907)

and Under Western Eyes (1911) and, even earlier, José Rizal’s El Filibusterismo, viewed it both from without and from within

the mind of the perpetrator. These, together with a host of memoirs, generated

a curious interplay of literary form and actuality.12 In Paris, ‘crime

factories’ churned out sensational fiction; in 1908, the journal Le Parisien

gave over 12 percent of its column space to it. This magnified the idea of

‘investigation’ in modern society, where lives were enacted in front of

reporters, forensic scientists, policemen, and private detectives.13 The theme

was soon taken up in the Romans-feuilletons read in Japan and China, and

elsewhere.

In the anarchist

panics of the 1880s and early 1890s, secret police practices became globalized.

After the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, the Okhrana extended its

informers' reach and even operated freely out of its own building in Paris. New

forms of censorship, anti-socialist laws, and criminal conspiracy prosecution

all widened state power repertoires. An ‘International Conference of Rome for

the Social Defence against Anarchists’ in December

1898 further criminalized anarchism and entrenched the argument that it had ‘no

relation to politics.’ It advocated new measures, such as extradition across

borders for regicides. In 1903, in the wake of the assassination of President

William McKinley in 1901, anarchists became the first category of person to be

prohibited from entry to the United States on the grounds of political belief.

A St Petersburg ‘Secret Protocol for the International War on Anarchism’ in

March 1904 helped fashion a more standardized and professionalized police

culture across the globe. As one Italian anarchist, Pietro Vasai observed: ‘The

police are the same in all parts of the world’; they had become a highly

mobile, specialized global labor force, identified with imperial migrants such

as Sikh constables and watchmen.14 Following the Entente Cordiale of 1904

between Britain and France, their police forces shared information on Indian

and other activists across Europe, which was soon extended to colonial

territories.15 From the landlords and brothel-keepers, pimps, and prostitutes

who peopled the underside of the migrant world, they recruited an undercover

army of turncoats, informers, and agent provocateurs. This was the same terrain

that anarchists worked themselves.16 The policing of ports and railheads was

often in private hands. Security companies, such as Pinkertons, with their

detectives and ‘procurers,’ worked internationally in an extra-legal way to

break strikes and seize fugitives. They enforced borders before the states

themselves did and fed public paranoia about the anarchist peril. In the words

of Allan Pinkerton himself: ‘It was everywhere, it was nowhere.’17

Anarchism was the

quintessential ideology of exile: a state of being – displacement outside a

country – which embodied anarchist belief's anti-nationalism.18 The aftermath

of the Paris Commune sent a generation of sympathizers into exile and

imprisonment worldwide. Between 1864 and 1897, the French authorities despatched some 4,500 political prisoners – only twenty

women – to New Caledonia. Many were communards of 1871, spared the firing

squads to live alongside colonial rebels, Arabs and Berbers, and Vietnamese

laborers. Many died from what was diagnosed as ‘nostalgia’: a void of isolation

and unrelieved depression.19 More than 9 percent of Italians lived outside

Italy; among Italian anarchist editors, 20 percent had the experience of more

than one country – and 40 percent of all Italian anarchist publications were

produced abroad. The mystique of many anarchists was enhanced by extended

exiles far from home. Enrico Malatesta – one of the best-known European exiles

– spent time in Egypt, Argentina and Uruguay, Tunisia, the United States, and

England.20

The slogan ‘Nostra

Patria e il mondo intero’ – ‘Our homeland is the

whole world’ – was a lived experience. Its citizenship, as it were, came not

through allegiance to any formal organization, but from personal networks: from

the circulation of letters, pamphlets and newspapers; from the translation of

small pieces aimed at initiates as much as the masses; from encounters with

people passing through on propaganda tours; and from songs and theatre.21

2These ties could prove as strong as the more visible ones of kin and kind, and

resilient to the new forms of policing.22 In this way, radical ideas oscillated

worldwide, endlessly syndicated and taken up, reshaped by local circumstances,

and exported again. Hence, it was impossible to say who had thought of what

first. It was a Pentecost rather than a movement.23 At the very moment that

anarchist ideas began to capture radicals' imagination in Europe, they were

also at large in Asia. They were present with the first wave of Russian exiles

to Japan, beginning with Mikhail Bakunin himself, who spent a month in Japan on

his escape from internal exile in Siberia in 1861. Some were adept in the

science of dynamite.24 In 1874, another Russian internationalist, Narodnik, Lev

Mechnikov, appeared in Japan. He arrived from the

United States, competent in Japanese and with excellent introductions to the

country’s intellectuals from those he had met in Europe. Over the next two

years, while teaching at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages, he saw in the

Meiji revolution’s search for knowledge, everyday collaboration, and

solidarity. It was a premonition of the general human evolution towards a

cooperative civilization. He understood that Japanese use of European ideas was

selective and a manifestation of a deeper communitarian ethic, rather than, as

most other Europeans saw it, part of an evolutionary flow of reason and

progress from the west to the east. On Mechnikov’s

return to Europe, his writings had a profound impact on Reclus's likes – with

whom he worked closely on the Nouvelle Géographie Universelle – Georgi Plekhanov and Kropotkin. This was

especially true of Kropotkin’s collection of essays Mutual Aid: A Factor of

Evolution (1902), which, by a circumnavigation from east to west to east again,

was reintroduced to Japan by the time of the Russo-Japanese War, and from the

Japanese translated into Chinese. It was as if Kropotkin merely explained and

clarified ideals they already cherished to many Japanese readers as their

own.25

Kropotkin's principal

Japanese translator was Kotoku Shusui,

author of Teikokushugi: Nijuseiki

no kaibutsu (1901), or Imperialism: The Monster of

the Twentieth Century and co-founder in 1896 of the Society of the Study of

Socialism. He had read Kropotkin and corresponded with him on a visit to the

United States in 1905, following a prison sentence for his opposition to the

Russo-Japanese War. Kotoku argued that both the war

and the terms of the concluding peace treaty would lead to further imperial

competition, instability, and violence, and that ‘true progress’ lay in

extending anarchist forms of mutuality and cooperation into the international

sphere. He was an early enthusiast for Esperanto, and, during the relatively

liberal period of Japanese politics in 1906, a founder of the Japanese

Socialist Party. In the midst of the party’s factionalism, anarchism's

collaborative ideal ideas a powerful common ground.26 They were present too at

the Asian Solidarity Association meeting in 1907 when Kotoku

chided the Asian movements for failing to ‘go beyond demands for national

independence.’ He urged the patriots gathered in Tokyo to go further in making

anarchism the foundation of the new Asia: ‘if the different revolutionary

parties of Asia start to look beyond differences of race or nation they will

form a grand confederation under the banner of socialism and one-worldism. East Asia of the twentieth century will be the

land of revolution.’27

It was almost a new

dawn. Kotoku’s 1901 critique of ‘imperialism’ had

preceded and gone further than J. A. Hobson, Lenin, and others in the west.

Within a year, it had been translated into Chinese and 1906 into Korean. The

Chinese organizers of the Asian Solidarity Association had embraced anarchist

ideas. Even Phan Boi Chau, representing Vietnam, was part of the anarchist

grouping at the meeting. He shared the euphoric mood of unity, but it is

unclear how he was of delegates’ diverse ideological positions. By no means all

of them identified as anarchists or embraced the propaganda of the

deed.28

Within three years,

dark repression struck. In June 1910, a Japanese worker was arrested and

accused of making bombs. The police claimed to have uncovered an extensive

assassination plot against Emperor Meiji, and there was a general round-up of

alleged socialists suspected of high treason. Among those snared was Kotoku, who worked on his translation of Kropotkin’s The

Conquest of Bread (1892) at a hot-spring resort. In the trials that followed in

early 1911, twenty-six conspirators were condemned to be hanged. Although

twelve of the guilty were reprieved by the emperor at the last moment, another

twelve were executed within three days of their sentencing. Kotoku

and his lover, the journalist and feminist Kanno Sugako, were the final two to

be hanged.29

Known as

the High Treason Incident (大逆事件, Taigyaku Jiken), also

known as the Kōtoku Incident (幸徳事件, Kōtoku Jiken), provoked an

unprecedented press blackout with the trials held in camera. Nevertheless, in

the way it polarized opinion, it became the ‘Dreyfus Affair of Japan.’ Not all

of those indicted were intellectuals, and not all the intellectuals – including

Kotoku – were active in bomb-making or even endorsed

violence. For many, it seemed that the only charge proven against Kotoku was that of his anarchist beliefs.30 As the poet

Ishikawa Takuboku wrote in June 1911:

Though I used to feel

quite remote from

The sad mind of the

terrorists –

Some days recently, I

feel it coming close.31

The Japanese

authorities reaffirmed the emperor's authority as the center of the nation, and

the Special Higher Police deepened its surveillance of his subjects' thoughts.

Many socialists and anarchists withdrew from public life; some committed

suicide, others fled abroad, such as the close associate of Kotoku,

Sen Katayama, who moved to the United States and was soon prominent in activist

circles there. By 1910 most Chinese anarchists in Japan had moved on to Paris

to join the schools and newspapers founded for the work-study group there. The

trial and executions were reported in anarchist journals in London, Paris, and

the Americas as part of a worldwide attack on the anarchist idea.32

Kanno Sugako’s

involvement in the plot was more direct than Kotoku’s

own and went beyond acting as a courier or helpmate. She was a thinker in her

own right, and her troubled life moved many across Asia, her ‘free love’ with Kotoku, and her cruel execution. In the words of a

‘farewell missive’ from her friend, Koizumi Sakutara,

Kanno copied as one of the final entries into her prison journal: ‘How pitiful.

This enlightened age derails the talented woman.’33 The feminist circles

occupied by women such as Kanno were a site for new experiments in thinking

that did not see the women’s movements in Europe, America, or even Japan as the

yardstick for female emancipation, unlike many male reformers. Moving amid

them, the Chinese feminist thinker He-Yin Zen drew on radical anarchist

critiques of the state to envisage fundamentally new forms of social life,

beginning with a rejection of existing forms of family and property. In her

journal Tianji Bao (Natural Justice), published in

Tokyo between 1907 and 1908, excerpts from The Communist Manifesto reached a

Chinese readership for the first time – specifically, the burgeoning audience

for new periodicals and translations among women.34

This world might be

formless and fluid, but it had its recurring and intersecting circulations and

its own rhythm. In his early writings, Karl Marx had a premonition of this, of

the moment world history came into being: when capitalism could no longer satisfy

its needs within one country, but ‘chases the bourgeoisie over the whole

surface of the world’: From this, it follows that this transformation of

history into world history is not indeed a mere abstract act on the part of the

‘self-consciousness,’ the world spirit, or of any other metaphysical specter,

but a quite material, empirically verifiable act, an act the proof of which

every individual furnishes as he comes and goes, eats, drinks and clothes

himself.35 In this sense, these mobile Asians abroad were among the first

people to experience world history. They experienced it not as an idea but by

coming and going, as workers and also as colonial subjects, in a way that

brought capitalism and imperialism closer together in their worldview. Liminal

spaces – locations of sudden displacement and new solidarities little

understood by metropolitan elites, such as port city slums and the mining and

plantation frontiers of the tropical colonies – became the foci of

world-historical change. In this context, as a doctrine of self-help and

self-governance, anarchism, as a vision of internationalism and a world less

patriarchal, began to insinuate itself into the village abroad, carried by the

new workers of the global economy of movements, such as seamen and dockhands.36

Anarchism was well adapted to their mixed labor forces of the waged, the

unwaged, and the casual, which defied the kinds of conventional ‘class’

analysis that were the staple of Marxist inquiry in Europe.37 These broad

coalitions had already led boycotts in Asia and would do so again in new

‘general’ labor unions.

Anarchists were also

more willing than other radicals to give countenance to the underworld of

labor. As an early anarchist newspaper in Buenos Aires celebrated it in 1890:

‘We are the vagrants, the malefactors, the rabble, the scum of society, the

sublimate corrosive of the present social order.’ This itself was an echo of

protest forms in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, during the first

global age of empire, when motley crews, slaves, drifters, and pirates had

combined in a world of resistance across shorelines and oceans. It was seen at

the time by those in authority as a ‘many-headed hydra’ and left behind a

freewheeling vision of liberty and folk memory of places outside empires and

their authority.38

Marx and Bakunin

shared an image of how the radical spirit survived under the weight of

capitalist oppression: the underground. Its source was Hamlet’s quip to his

father’s ghost: ‘Well said, old mole. Canst work the ground so fast? / A worthy

pioneer!’ G. W. F. Hegel took this as a metaphor for the spirit of the

philosophy of history, which ‘often seems to have forgotten and lost itself,

but inwardly opposed to itself, it is inwardly working ever forward … until

grown strong in itself it bursts asunder the crust of earth which divided it

from the sun, its Notion so that the earth crumbles away’.39 And so the

underground idea was taken up in this new age of empire by the kinds of

itinerant leadership that were emerging from the waterfronts and railheads of

the empire, harrying, disappearing, burrowing, and then resurfacing somewhere

else, far away. The imperial underground now confronted western power in Asia

with the logic of its own globalism: that it too might crumble away.

'A Passage to India'

At the center of the

western condominium over Asia was the British Raj in India. It was a world

system in its own right, centered not on London but its seat of power in Calcutta. It formed the midpoint

of an arc encompassing the Indian Ocean and beyond, eastwards to Singapore and

Hong Kong, down towards the southern Dominions, westwards from Bombay into the

Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, and down the coast of Africa. The British

occupation of Egypt in 1882 threaded new ‘red routes,’ in the form of

garrisons, post offices and telegraph relay stations, through the eastern

Mediterranean and, via Malta and Gibraltar, into the home waters of the British

Isles. Singapore took on a new strategic significance as the Clapham Junction

of the East. This great arc helped defend the Raj approaches, and the Raj

supplied the circulations of people that gave it unity. Punjabi constables and

guards guarded western interests in Southeast Asia and the foreign concessions

in China. Sindhi merchants set up shop in Malta, Bukhara, Kobe, and Panama, and

Bengali or Malabari clerks staffed colonial secretariats, land offices, and

railway stations from Mombasa to Malaya. Plantation laborers recruited in Calcutta,

Bombay, and Madras hewed out human cultivation and settlement frontiers across

three oceans. The 200,000 or so men in Raj's arms garrisoned the far-flung

outposts that allowed Great Britain to imagine herself a terrestrial instead of

the maritime power of consequence. And it was the vastness of this domain that

allowed British statesmen to think in classical ‘imperial’ terms. The only

occasion when British sovereigns assumed an imperial style was in their guise

as Kaiser-i-Hind – a title by which the British

claimed the inheritance of the Mughal empire, bestowed on Queen Victoria, in

her absence, at the imperial Durbar, or grand levée, held in Delhi in

1877.40 Britain’s unchallenged paramountcy in Asia stabilized the entire

imperial order, for a time.

In the new century,

the Raj was beset by political and strategic challenges and by self-doubt. In

1904 the British geographer Halford Mackinder announced the end of ‘the

Columbian epoch.’41 Western maritime conquest had reached its furthest extent;

all that remained was securing its internal frontiers in contested border

regions. In a more imaginative sense, the limits of the ‘human empire’ had been

reached, and with this came a gnawing sense of vulnerability and

decay.42 The arrival of competitors such as Germany and Japan brought new

conundrums to the so-called ‘Great Game,’ the clandestine scheming for hegemony

in Central Asia. Never mere play, this was prosecuted with lethal seriousness

by a growing phalanx of specialist soldiers and spies, cartographers, and

cryptographers.43 Yet, despite this, the number of Britons governing India was

famously small, around 1,000 in the Indian Civil Service, with perhaps 1,000

more in the police. Over two-fifths of the Raj territory, comprising some 565

princely states, was ruled by proxy. The ‘steel frame’ of the Raj was very

uneven. It was government by smoke and mirrors. After the attrition of decades

of warfare across the empire's arc, there was a growing risk that the

underlying trickery might be exposed in Egypt, Sudan, Burma, and on the

Northwest Frontier. In the highest circles of the Raj, it was possible to

discern doubt and pessimism. Britain, the viceroy, Lord Lytton, feared in 1878,

was ‘losing the empire's instinct and tact.’ Others foresaw the Raj being swamped

by its own collaborators, the rising elites within Indian society, or, in the

Darwinian language of the day, being fatally enfeebled by its own racial

degeneration.44 In truth, the Raj had never emerged from the shadow of the

Indian Mutiny-Rebellion of 1857. The British lived in eternal fear of sedition

among Raj’s Indian troops, especially those posted overseas or fomented by ‘mad

mullahs’ and mahdis: the Muslim outlaws – Sufis,

scribes, and go-betweens – who moved between the various imperial constellations

in Asia and the Middle East. Such men grafted a rival Muslim connectedness to

consuls' western networks, shipping lanes, and law, which the British never

fully understood.45 These mobile subjects mastered empire as a system before

the British ever did.

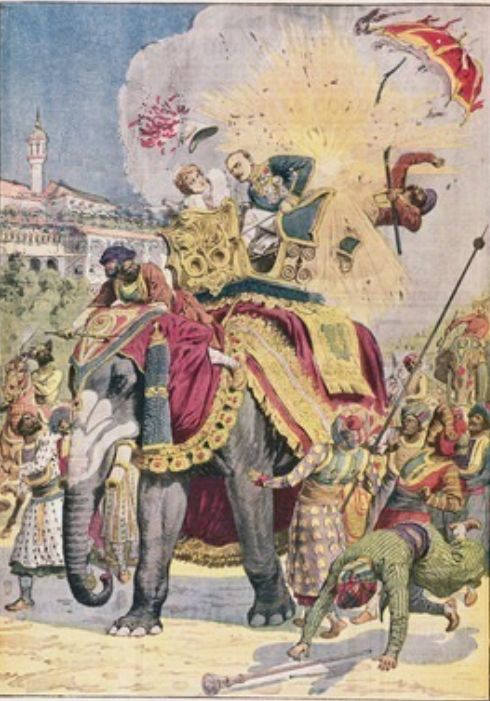

Next was up to Lord

Charles Hardinge, who served as India's new viceroy, to make it public. In

1912, Viceroy Hardinge entered Old Delhi atop the biggest elephant he had ever

seen. Lord Hardinge mounted the giant beast with his wife, Winifred, at his

side and two attendants to accompany them. The procession moved off, led by the

Royal Artillery and the Enniskillen Dragoons; then came Lord Hardinge’s own

bodyguard and staff; and, immediately preceding the viceroy, the Imperial Cadet

Corps on black chargers, resplendent in snow-leopard skins. To Hardinge’s rear,

his council flowed behind him on fifty carefully picked elephants. Then,

somewhat diminished by having to ride on horseback this time, but still

resplendent in their royal accouterments, came the rulers of Punjab: the

Princes of Patiala, Jind, Nabha, Kapurthala, Maler Kotla, Faridkot, and others.

The legendary frontier cavalry of the 3rd Skinner’s Horse brought up the rear.

At 11.45 a.m., the

viceroy passed the building of the Punjab National Bank; it was some 300 yards

down Chandni Chowk, at a point halfway between the gothic Clock Tower and the

Fountain. The elephant halted, and there was a sudden silence. The bomb deafened

the viceroy and his wife before the sound of it could reach them. Hardinge saw

his pith helmet in the road. He turned first to his wife, saw that she was

unscathed, and then to the back of the howdah, where he noticed some yellow

powdery residue. The viceroy turned again to his wife and said: ‘I am afraid

that was a bomb.’ ‘Are you sure you are not hurt?’ ‘I am not sure. I have had a

great shock, but I think I can go on.’ He felt as if someone had struck him in

the back and poured boiling water over him. The Viceroy escaped with flesh

wounds, but the servant behind him holding his parasol was killed. And his wife

never fully recovered from the shock, dying soon afterward.46

Henceforth called the

Delhi Conspiracy case or Delhi-Lahore Conspiracy. It was later shown that Rash

Behari Bose threw the bomb. He successfully evaded capture for nearly three

years, becoming involved in the Ghadar conspiracy before it was uncovered. Bose

fled to Japan in 1915, under the alias of Priyanath

Tagore, a relative of Rabindranath Tagore. There, Bose found shelter with

various Pan-Asian groups. Though more expensive than the usual

"British-style" curry, it became quite popular, with Rash Bihari becoming

known as "Bose of Nakamuraya.47

1. Margaret C. Jacob,

Strangers Nowhere in the World: The Rise of Cosmopolitanism in Early Modern

Europe, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

2. Tom Genrich,

Authentic Fictions: Cosmopolitan Writing of the Troisième

République, 1908–1940, Oxford, Peter Lang, 2004, pp. 21–2.

3. Constance Bantman, ‘Internationalism without an International? Cross-Channel Anarchist Networks, 1880–1914’, Revue Belge

de Philologie et d’Histoire, 84/4 (2006), pp. 961–81.

4. For a general

introduction to (mostly) western anarchism, see Peter Marshall, Demanding the

Impossible: A History of Anarchism, Oakland, CA, PM Press, 2010; Carl Levy,

‘Anarchism, Internationalism and Nationalism in Europe, 1860–1939’, Australian

Journal of Politics and History, 50/3 (2004), pp. 330–42.

5. Federico Ferretti,

‘“They Have the Right to Throw Us Out”: Élisée Reclus’ New Universal

Geography,’ Antipode, 45/5 (2013), pp. 1337–55. As Ferretti notes, others have

compared the writing of Dipesh Chakrabarty over a century later: see esp.

Chakrabarty’s Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical

Difference, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 2000.

6. John P. Clark and

Camille Martin (eds), Anarchy, Geography, Modernity: The Radical Social Thought

of Elisée Reclus, Lanham, MD, Lexington Books, 2004,

pp. 72–4.

7. Arif Dirlik, ‘Vision and Revolution: Anarchism in Chinese

Revolutionary Thought on the Eve of the 1911 Revolution’, Modern China, 12/2

(1986), pp.123–65, at pp. 126–7.

8. For this point and

a challenge to Eurocentrism in histories of anarchism, see Steven Hirsch and

Lucien van der Walt (eds), Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and

Postcolonial World, 1870–1940: The Praxis of National Liberation,

Internationalism, and Social Revolution, Leiden, Brill, 2010, esp. the editors’

introduction. For a similar review, see also Carl Levy, ‘Social Histories of

Anarchism’, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 4/2 (2010), pp. 1–44.

9. David E. Apter,

‘Notes on the Underground: Left Violence and the National State,’ Daedalus,

108/4 (1979), pp. 155–72, a quotation from Babeuf at p. 159.

10. Martin A. Miller,

‘The Intellectual Origins of Modern Terrorism in Europe,’ in Martha Crenshaw

(ed.), Terrorism in Context, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania State University Press,

1995, pp. 27–62.

11. For a useful

introduction, see Olivier Hubac-Occhipinti,

‘Anarchist Terrorists of the Nineteenth Century’, in Gérard Chaliand and Arnaud

Blin (eds), The History of Terrorism: From Antiquity to Al Qaeda, Berkeley,

University of California Press, 2007, pp. 113–31.

12. Bill Melman, ‘The

Terrorist in Fiction’, Journal of Contemporary History, 15/3 (1980), pp.

559–76.

13. Dominique Kalifa,

‘Criminal Investigators at the Fin-de-Siècle’, Yale French Studies, 108 (2005),

pp. 36–47.

14. Richard Bach

Jensen, The Battle against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History,

1878–1934, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013; Mathieu Deflem, Policing World Society: Historical Foundations of

International Police Cooperation, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002; Clive

Emsley, ‘The Policeman as Worker: A Comparative Survey, c.1800–1940’,

International Review of Social History, 45/1 (2000), pp. 89–110. For Vasai see

Lucia Carminati, ‘Alexandria, 1898: Nodes, Networks, and Scales in Nineteenth-Century

Egypt and the Mediterranean’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 59/1

(2017), pp. 127–53, at p. 136.

15. Daniel Brückenhaus, Policing Transnational Protest: Liberal

Imperialism and the Surveillance of Anti-Colonialists in Europe, 1905–1945, New

York, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 9–12.

16. See, for example,

Charles van Onselen, ‘Jewish Police Informers in the Atlantic World,

1880–1914’, Historical Journal, 50/1 (2007), pp. 119–44.

17. Martin A. Miller,

The Foundations of Modern Terrorism, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press,

2013, p. 126. See also Katherine Unterman, ‘Boodle over the Border:

Embezzlement and the Crisis of International Mobility, 1880–1890’, Journal of

the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 11/2 (2012), pp. 151–89.

18. Important recent

reassessments are: Maia Ramnath, Decolonizing Anarchism: An Antiauthoritarian

History of India’s Liberation Struggle, Oakland, CA, AK Press, 2012; Constance Bantman and Bert Altena (eds), Reassessing the

Transnational Turn: Scales of Analysis in Anarchist and Syndicalist Studies,

New York, Routledge, 2015.

19. Alice Bullard,

‘Self-Representation in the Arms of Defeat: Fatal Nostalgia and Surviving

Comrades in French New Caledonia, 1871–1880’, Cultural Anthropology, 12/2

(1997), pp. 179–212.

20. Davide Turcato, ‘Italian Anarchism as a Transnational Movement,

1885–1915’, International Review of Social History, 52/3 (2007), pp.

407–44.

21. Ibid.

22. I am thinking

here of Mark S. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak

Ties’, American Journal of Sociology, 78/6 (1973), pp. 1360–80. For an

elaboration of this see Andrew Hoyt, ‘Active Centers, Creative Elements, and

Bridging Nodes: Applying the Vocabulary of Network Theory to Radical History’,

Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 9/1 (2015), pp. 37–59.

23. Bruce Nelson used

this image of Pentecost to describe the unionization of maritime labor in the

1930s: see his Workers on the Waterfront: Seamen, Longshoremen, and Unionism in

the 1930s, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1988, p. 2.

24. Yin Cao, ‘Bombs

in Beijing and Delhi’, pp. 586–7.

25. Sho Konishi,

Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese–Russian

Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University

Press, 2013, esp. pp. 29–73 and ch. 3; John Crump,

The Origins of Socialist Thought in Japan, London, Routledge, 2010.

26. George M.

Beckmann and Genji Okubo, The Japanese Communist Party, 1922–1945, Stanford,

CA, Stanford University Press, 1969, pp. 1–7; Thomas A. Stanley, Ōsugi Sakae,

Anarchist in Taishō Japan: The Creativity of the Ego,

Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1982.

27. Quoted in Robert

Thomas Tierney, Monster of the Twentieth Century: Kotoku

Shusui and Japan’s First Anti-Imperialist Movement,

Berkeley, University of California Press, 2015, pp. 119–21.

28. See Hue-Tam Ho

Tai, Radicalism and the Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution, Cambridge, MA,

Harvard University Press, 1992, pp. 58–62; and, for a more cautious view, see

Daniel Hémery’s review of Tai’s study, Journal of

Southeast Asian Studies, 24/2 (1993), pp. 461–3.

29. Ira L. Plotkin,

Anarchism in Japan: A Study of the Great Treason Affair, 1910–11, Lewiston, ME,

Edwin Mellen Press, 1990.

30. For the Dreyfus

analogy see Peter F. Kornicki, ‘General

Introduction’, in Kornicki (ed.), Meiji Japan, vol.

I: The Emergence of the Meiji State, London, Routledge, 1998, pp. xiii–xxxiii,

at p. xxviii. For the trial itself see Plotkin, Anarchism in Japan.

31. Yukinori Iwaki,

‘Ishikawa Takuboku and the Early Russian

Revolutionary Movement’, Comparative Literature Studies, 22/1 (1985), pp.

34–42, at p. 39.

32. Tanaka Mikaru, ‘The Reaction of Jewish Anarchists to the High

Treason Incident’, in Masako Gavin and Ben Middleton (eds), Japan and the High

Treason Incident, London, Routledge, 2013, pp. 80–88.

33. For this

remarkable prison testament see Mikiso Hane,

Reflections on the Way to the Gallows: Rebel Women in Prewar Japan, Berkeley,

University of California Press, 1988, pp. 51–74, quotation at p. 74.

34. Liu, Karl and Ko

(eds), The Birth of Chinese Feminism, pp. 1–48; Rebecca Karl, ‘Feminism in

Modern China’, Journal of Modern Chinese History, 6/2 (2012), pp. 235–55.

35. Karl Marx and

Frederick Engels, The German Ideology Part One, ed. C. J. Arthur, London,

Lawrence & Wishart, 1970, p. 58. The preceding quotation is from Gareth

Stedman Jones (ed.), The Communist Manifesto, London, Penguin, 2002, p. 223.

36. Levy, ‘Social

Histories of Anarchism’, esp. pp. 15–16.

37. A subject central

to recent debates on ‘global labor history’: see Marcel van der Linden, ‘The

Promise and Challenges of Global Labor History’, International Labor and

Working-Class History, 82 (2012), pp. 57–76, at pp. 63–4, and the responses to

this article in the same issue.

38. For these themes

see Geoffroy de Laforcade, ‘Federative Futures:

Waterways, Resistance Societies and the Subversion of Nationalism in the Early

20th-Century Anarchism of the Río de la Plata Region’, Estudios

Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe, 22/2 (2011), pp. 71–96; Jose C. Moya, ‘The

Positive Side of Stereotypes: Jewish Anarchists in Early-Twentieth-Century

Buenos Aires’, Jewish History, 18/1 (2004), pp. 19–48; and Peter Linebaugh and

Marcus Rediker’s inspiring The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners,

and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, Boston, MA, Beacon Press,

2000.

39. Jesse Cohn,

Underground Passages: Anarchist Resistance Culture 1848–2011, Oakland, CA, AK

Press, 2015, p. 4; Peter Stallybrass, ‘“Well Grubbed,

Old Mole”: Marx, Hamlet, and the (Un) Fixing of Representation’, Cultural

Studies, 12/1 (1998), pp. 3–14. 3.

40. Sugata Bose, A

Hundred Horizons: The Indian Ocean in the Age of Global Empire, Cambridge, MA,

Harvard University Press, 2006; Thomas R. Metcalf, Imperial Connections: India

in the Indian Ocean Arena, 1860–1920, Berkeley, University of California Press,

2007.

41. H. J. Mackinder,

‘The Geographical Pivot of History’, The Geographical Journal, XXIII/4 (1904),

pp. 421–44, at p. 421.

42. Rosalind

Williams, The Triumph of Human Empire: Verne, Morris, and Stevenson at the End

of the World, Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press, 2013.

43. James L.

Hevia, The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and

Empire-Building in Asia, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2012, esp. pp.

11–14.

44. Ronald Hyam,

Britain’s Imperial Century, 1815–1914, 2nd edn,

London, Macmillan, 1993, p. 190. See also Jon Wilson, India Conquered:

Britain’s Raj and the Chaos of Empire, London, Simon & Schuster,

2016.

45. Seema Alavi,

‘“Fugitive Mullahs and Outlawed Fanatics”: Indian Muslims in Nineteenth-Century

Trans-Asiatic Imperial Rivalries’, Modern Asian Studies, 45/6 (2011), pp.

1337–82, quotation at p. 1342.

46. Charles Hardinge Hardinge of Penshurst, My Indian

years, 1910-1916;: The reminiscences of Lord Hardinge of Penshurst,

1948, pp. 79–81, and Lady Hardinge’s account, as reported in the New York

Times, 9 February 1913

47. On this subject

see Takeshi Nakajima, Bose of Nakamuraya: An Indian Revolutionary in Japan,

2009.

For updates click homepage here