With protesters who

have created an “Autonomous Zone” in the center of Seattle, A&E announcing

today that itis stopping production of "Live PD", various mayors in

the US that ban chokehold, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti who said today that

the United States past few days have been traumatic. Also, black scientists and

students are sharing their experiences many who will be participated in a June 10th strike meant to shut down STEM

industries in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Not to mention that

after protesters toppled a statue of the British slave trader Edward Colston in

Bristol, England, dozens of English cities are considering taking down

monuments commemorating controversial figures. The statue of the Belgian King

Leopold II in Antwerp has already been removed because of his brutal colonial

rule in the Congo. Granted many commentators believe this is not the right

approach to dealing with history. In fact, a better place for these statues

that instead of throwing them in a river a more proper place would be a museum

what are left with however is that George Floyd was not famous. He was killed

not in the capital of the United States, but on a street corner in its

46th-largest city. Yet in death, he has suddenly become the keystone of a

worldwide movement. He has inspired protests abroad, from Brazil to Indonesia,

and France to Australia. His legacy is the rich promise of social reform. It is

too precious to waste.

The focus is rightly

on America. The protests there, in big cities and tiny towns far from the

coasts, maybe the most widespread in the country’s long history of marching.

After an outburst of rage following Floyd’s death, the demonstrations have, as

we hoped last week, been overwhelmingly peaceful. They have drawn in ordinary

Americans of all races. That has confounded those who, like President Donald

Trump, though they could be exploited to forge an electoral strategy based on

the threat of anarchy. What began as a protest against police violence against

African-Americans has led to an examination of racism in all its forms.

The marches outside

America are harder to define. In Mexico and South Africa, the target is mainly

police violence. In Brazil, where three-quarters of the 6,220 people killed by

police in 2018 were black, the race is a factor too. Australians are talking

about the treatment of aboriginals. Some Europeans, used to condemning America

over race, are realizing that they have a problem closer to home.

It is hard to know

why the spark caught today and not before. Nobody marched in Paris in 2014

after Eric

Garner was filmed being choked to death by officers on Staten Island—then

again, hardly anyone marched in New York, either. Perhaps the sheer ubiquity of

social media means that enough people have this time been confronted with the

evidence of their own eyes. The pandemic has surely played a part, by cooping

people up and creating a shared experience, even as it has nonetheless singled

out racial minorities for infection and hardship.

The scale of the

protests has something to do with Trump, too. When Garner was killed, America

had a president who could bring together the nation at moments of racial

tension, and a Justice Department that baby-sat recalcitrant police

departments. Today they have a man who sets out to sow division.

But most

fundamentally the protest reflects a rising rejection of racism itself. Most

people in the US say police

more likely to use excessive force on black individuals. Inspired by German

legislation that came into force in 2018, Laetitia Avia, a black French MP

hopes the new law will form the foundation of a wider European

push to tackle racism, anti-Semitism, sexism, and homophobia peddled by

usually anonymous users of social media. The vast majority of Britons

agree that racism remains a problem in the UK.

America is both a

country and an idea. When the two do not match, non-Americans notice more than

when an injustice is perpetrated in, say, Mexico or Russia. And wrapped up in

that idea of America is a conviction that progress is possible.

It is already

happening, in three ways. It starts with policing, where some states and cities

have already banned chokeholds and where Democratic politicians seem ready to

take on the police unions. On June 8th Democrats in the House of

Representatives put forward a bill that would, among other things, make it

easier to prosecute police and limit the transfer of armor and weapons from the

Pentagon to police departments. Congressional Republicans, who might have been

expected to back the police, are working on a reform of their own. Although the

general call for “defunding” risks a backlash, the details of redirecting part

of the police budget to arms of local government, such as housing or mental

health, may make sense.

There is also a

recognition that broader change is needed from the local and federal

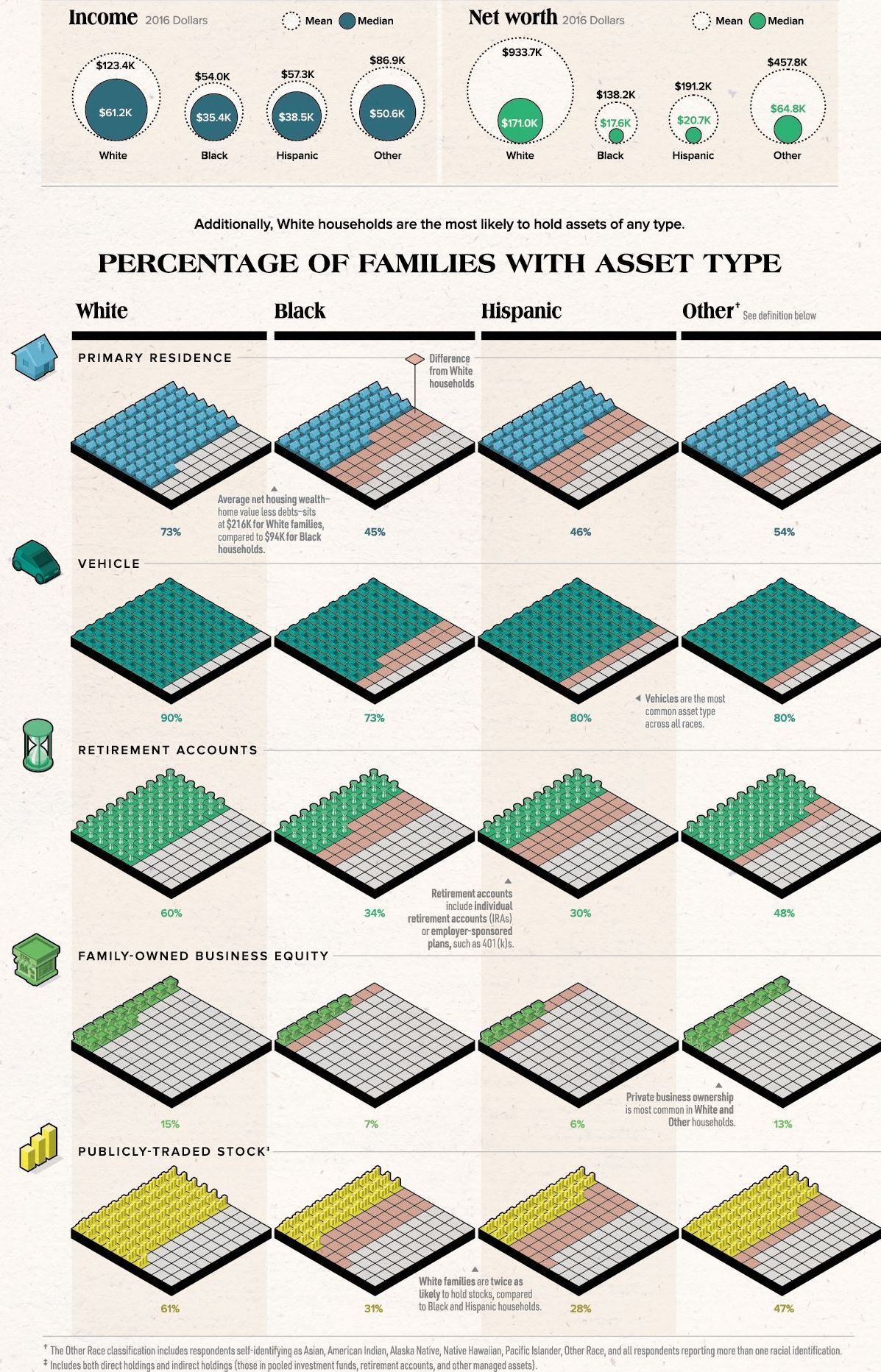

governments. The median household net wealth of African-Americans is $18,000, a

tenth of the wealth of white Americans. The ratio has not changed since 1990.

An important cause of this is that many African-Americans are stuck in the

racially monolithic neighborhoods where their grandparents were allowed to

settle at a safe distance from whites. Houses in these places are very cheap.

This separation helps

explain why inequality endures in schooling, policing, and health. The

government has a role in reducing it. Federal spending worth $22.6bn already

goes on housing vouchers. Schemes to give poor Americans a choice over where

they live have Republican and Democratic backing in Congress. With better

schools and less crime, segregated districts become gentrified, leaving them

more racially mixed.

Business is waking up

to the fact that it has a part, too, and not just in America. The place where

people mix most is at work. However, just four Fortune 500 firms have black

chief executives and only 3% of senior American managers are black. No wonder anxious

ceos have been queuing up to pledge that they will do

better.

Firms have an

incentive to change. Research suggests that racial diversity is linked to

higher profit margins and that the effect is growing, though it is hard to be

certain which comes first, diversity or performance. It has also become clear

that a vocal share of employees and customers will shun companies that do not

deal with racism. Platitudinous mission statements are unlikely to provide much

protection. A first step is to monitor diversity at all levels of recruitment

and promotion, as did Goldman Sachs and Intel, hardly known for being

sentimental.

Large-scale social

change is hard. Protest movements have a habit of antagonizing the moderate

supporters they need to succeed. Countries, where the impulse for change is not

harnessed to specific reforms, will find that it dissipates. Yet anyone who thinks

racism is too difficult to tackle might recall that just six years before

George Floyd was born, interracial marriage was still illegal in 16 American

states. Today about 90% of Americans support it. When enough citizens march

against injustice, they can prevail. That is the power of protest.

For updates click homepage here