By Eric Vandenbroeck

Researchers including

sociologists, historians and of course chronologists care about the Julian calendar

because it was used worldwide for over 16 centuries. Some, for example, the

Christian Eastern Orthodox Church, still use the Julian calendar to this day.

Also, equinoxes and solstices and

any lunar and

solar eclipses happening before October 15, 1582, are still dated by the

Julian calendar.

Not everyone

converted to the new calendar at the same time. England, for example, with its

large empire and separate

church kept its separate calendar, too, the Julian calendar, for another

two centuries.

The year 46 B.C., a

year before Julius Caesar implemented his namesake the Julian Calendar system,

lasted 445 days and later became known as the "final

year of confusion."

In other words, the

systems used by mankind to track, organize and manipulate time have often been

arbitrary, uneven and disruptive, especially when designed poorly or foisted

upon an unwilling society. The history of calendrical reform has been shaped by

the egos of emperors, disputes among churches, the insights of astronomers and

mathematicians, and immutable geopolitical realities. Attempts at improvements

have sparked political turmoil and commercial chaos, and seemingly rational

changes have consistently failed to take root.

So what is the matter with the Gregorian calendar?

The original goal of

the Gregorian calendar was to change the date of Easter. The Gregorian as a

reform of the Julian calendar was instituted by papal bull Inter gravissimas dated 24 February 1582 by Pope Gregory

XIII, after whom the calendar is named. The motivation for the adjustment was

to bring the date for the celebration of Easter to the time of year in which it

was celebrated when it was introduced by the early Church. The error in the

Julian calendar (its assumption that there are exactly 365.25 days in a year)

had led to the date of the equinox according to the calendar drifting from the

observed reality, and thus an error had been introduced into the calculation of the date of Easter.

Although a recommendation of the First Council of

Nicaea in 325 specified that all Christians should celebrate Easter on the

same day, it took almost five centuries before virtually all Christians

achieved that objective by adopting the rules of the Church of Alexandria.

The Julian calendar

included an extra day in February every four years. But Aloysius Lilius, the

Italian scientist who developed the system Pope Gregory would unveil in 1582,

realized that the addition of so many days made the calendar slightly too long.

He devised a variation that adds leap days in years divisible by four unless

the year is also divisible by 100. If the year is also divisible by 400, a leap

day is added regardless. While this formula may sound confusing, it did resolve

the lag created by Caesar’s earlier scheme, almost.

One can also say that

at its core, the modern calendar was an attempt to track and predict the

relationship between the sun and various regions of the earth. Historically,

agricultural cycles, local climates, latitudes, tidal ebbs and flows and

imperatives such as the need to anticipate seasonal change have shaped

calendars. The

Egyptian calendar, for example, was established in part to predict the

annual rising of the Nile River, which was critical to Egyptian agriculture.

This motivation is also why lunar calendars similar to the ones still used by

Muslims fell out of favor somewhat, with 12 lunar cycles adding up to roughly

354 days, such systems quickly drift out of alignment with the seasons.

Though it deviates

from the time it takes the earth to revolve around the sun by just 11 minutes

(a remarkable astronomical feat for the time), the Julian system overly

adjusted for the fractional difference in year length, slowly leading

to a misalignment in the astronomical and calendar years.

This whereby many say

the current system unnecessarily subjects businesses to numerous

calendar-generated financial complications like the scheduling of the days for

holidays, sporting events, and school schedules, to name but a few must

be redone each year.

The system resets

every leap year, slipping a little bit backward until a non-leap century year

leap nudges the equinoxes forward in time once again. The next leap day will be

added to the calendar on February 29, 2020.

Though Pope Gregory’s

papal bull reforming the calendar had no power beyond the Catholic Church,

Catholic countries, including Spain, Portugal, and Italy, swiftly adopted the

new system for their civil affairs. European Protestants, however, largely rejected

the change because of its ties to the papacy, fearing it was an attempt to

silence their movement. It wasn’t until 1700 that Protestant Germany switched

over, and England held out until 1752. Orthodox countries clung to the Julian

calendar until even later, and their national churches have never embraced

Gregory’s reforms.

A calendar as the onset of a globalized era

Thus what was perhaps

most significant about Pope Gregory's system was not its changes, but rather

its role in the onset of the globalized era. In centuries prior, countries

around the world had used a disjointed array of uncoordinated calendars, each

adopted for local purposes and based primarily on local geographical factors.

The Mayan calendar would not be easily aligned with the Egyptian, Greek,

Chinese or Julian calendars, and so forth. In addition to the pope's

far-reaching influence, the adoption of the Gregorian system was facilitated by

the emergence

of a globalized system marked by exploration and the development of

long-distance trade networks and interconnectors between regions beginning in

the late 1400s. The pope's calendar was essentially the imposition of a truly

global interactive system and the acknowledgment of a new global reality.

From the start,

however, the Gregorian calendar faced resistance from several corners, and

implementation was slow and uneven. The edict issued by Pope Gregory XIII

carried no legal weight beyond the Papal States, so the adoption of his

calendar for civil purposes necessitated implementation by individual

governments.

Though Catholic

countries like Spain and Portugal adopted the new system quickly, many

Protestant and Eastern Orthodox countries saw the Gregorian calendar as an

attempt to bring them under the Catholic sphere of influence. These states,

including Germany and England, refused to adopt the new calendar for a number

of years, though most eventually warmed to it for purposes of convenience in

international trade. Russia only adopted it in 1918 after the Russian

Revolution in 1917 (the Russian Orthodox Church still uses the Julian

calendar), and Greece, the last European nation to adopt the Gregorian calendar

for civil purposes, did not do so until 1923.

In 1793, following

the French Revolution, the new republic replaced the Gregorian calendar with

the French Republican calendar, commonly called the French Revolutionary

calendar, as part of an attempt to purge the country of any remnants of regime

(and by association, Catholic) influence. Due to a number of issues, including

the calendar's inconsistent starting date each year, 10-day workweeks and

incompatibility with secularly based trade events, the new calendar lasted only

around 12 years before France reverted to the Gregorian version.

Iran changing its calendar twice in a three year

period

The Shah of Iran

attempted an experiment amid competition with the country's religious leaders

for political influence. As part of a larger bid to shift power away from the

clergy, the shah in

1976 replaced the country's Islamic calendar with the secular Imperial calendar,

a move viewed by many as anti-Islamic, spurring opposition to the shah and his

policies. After the shah was overthrown in 1979, his successor restored

the Islamic calendar to placate protesters and to reach a compromise with

Iran's religious leadership.

Several countries,

Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia and Iran among them, still have not officially adopted

the Gregorian calendar. India, Bangladesh, Israel, Myanmar, and a few other

countries use various calendars alongside the Gregorian system, and still,

others use a modified version of the Gregorian calendar, including Sri Lanka,

Cambodia, Thailand, Japan, North Korea, and China. For agricultural reasons, it

is still practical in many places to maintain a parallel local calendar based

on agricultural seasons rather than relying solely on a universal system based

on arbitrary demarcations or seasons and features elsewhere on the planet. In

most such countries, however, the use of the Gregorian calendar among

businesses and others engaged in the international system is widespread.

Attempts to change the Gregorian calendar

Dozens of attempts

have been made over the years to improve the remaining inefficiencies in Pope

Gregory's calendar, all boasting different benefits.

In 1928, Eastman

Kodak founder George Eastman introduced a more business-friendly calendar (the

International Fixed calendar) within his company that was the same from year

to year and allowed numerical days of each month to fall on the same weekday,

for example, the 15th of each month was always a Sunday. This setup had the

advantage of facilitating business activities such as scheduling regular

meetings and more accurately comparing monthly statistics.

Reform attempts have

not been confined to hobbyists, advocates and academics. In 1954, the U.N. took

up the question of calendar reform at the request of India, which argued

that the Gregorian calendar creates an inadequate system for economic and

business-related activities.

In 2012, Richard Conn

Henry, a former NASA astrophysicist, teamed up with his colleague, an applied

economist named Steve H. Hanke, to introduce perhaps the most workable attempt

at calendrical reform to date. The

Hanke–Henry Permanent Calendar (itself an adaptation of a calendar

introduced in 1996 by Bob McClenon) is, as the pair wrote for the Cato

Institute in 2012, "religiously unobjectionable, business-friendly and

identical year-to-year."

The Hanke–Henry

Permanent Calendar would provide a fixed 364-day year with business quarters of

equal length, eliminating many of the financial problems posed by its Gregorian

counterpart. Calculations of interest, for example, often rely on estimates that

use a 30-day month (or a 360-day year) for the sake of convenience, rather than

the actual number of days, resulting in inaccuracies that, if fixed by the

Hanke-Henry calendar, its creators say, would save up to an estimated $130

billion per year worldwide. (Similar problems would still arise for the years

given an extra week in the Hanke-Henry system.)

Meanwhile, it would

preserve the seven-day week cycle and in turn, the religious tradition of

observing the Sabbath, the obstacle blocking many previous proposals' path to

success. As many as eight federal holidays would also consistently fall on

weekends; while this probably would not be popular with employees, the

calendar's authors argue that it could save the United States as much as $150

billion per year (though it is difficult to anticipate how companies and

workers would respond to the elimination of so many holidays, casting doubt

upon such figures).

Other proposals have

been the Holocene

calendar, the International

Fixed Calendar (also called the International Perpetual calendar), the World Calendar, the World Season

Calendar, the Leap

week calendars, the Pax

Calendar, the Symmetry454

calender.

Most reform proposals

have failed to supplant the Gregorian system not because they failed to improve

upon the status quo altogether, but because they either do not preserve the

Sabbath, they disrupt the seven-day week (only a five-day week would fit neatly

into a 365-day calendar without necessitating leap weeks or years) or they

stray from the seasonal cycle. And the possibilities of calendrical reform

highlight the difficulty of worldwide cooperation in the modern international

system. Global collaboration would indeed be critical since reform in certain

places but not in others would cause more chaos and inefficiency than already

exist in the current system. A tightly coordinated, carefully managed

transition period would be critical to avoid many of the issues that occurred

when the Gregorian calendar was adopted.

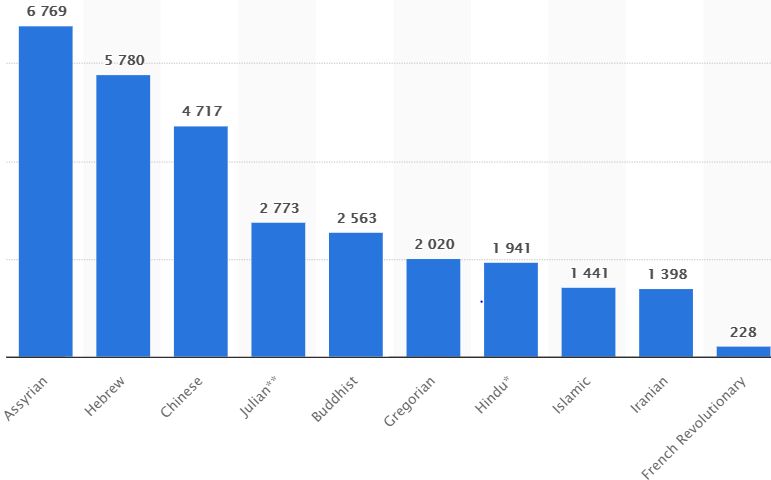

The current year

according to various historical and world calendars, as of January 01, 2020:

Today, in a more

deeply interconnected, state-dominated system that lacks the singularly

powerful voices of emperors or ecclesiastical authorities, who or what could

compel such cooperation? Financial statistics and abstract notions of global

efficiency are not nearly as unifying or animating as religious edicts, moral

outrage or perceived threats. Theoretically, the benefits of a more rational

calendar could lead to the emergence of a robust coalition of multinational

interests advocating for a more efficient alternative, and successes such as

the steady and continuous adoption of the metric system across the world

highlight how efficiency-improving ideas can gain widespread adoption.

But international

cooperation and coordination have remained elusive in far more pressing and

less potentially disruptive issues. Absent more urgent and mutually beneficial

incentives to change the system and a solution that appeals to a vast majority

of people, global leaders will likely not be compelled to undertake the

challenge of navigating what would inevitably be a disruptive and risky

transition to an ostensibly more efficient alternative.

Any number of factors

could generate resistance to change. If the benefits of a new calendar were

unevenly distributed across countries, or if key powers would in any way be

harmed by the change, any hope for a comprehensive global agreement would

quickly collapse. Societies have long adjusted to the inefficiencies of the

Gregorian system, and it would be reasonable to expect some level of resistance

to attempts to disrupt a convention woven so deeply into the fabric of everyday

life, especially if, say, the change disrupted cherished traditions or

eliminated certain birthdays or holidays. Particularly in societies already

suspicious of Western influence and power, attempts to implement something like

the Hanke–Henry

Permanent Calendar may once again spark considerable political opposition.

Even if a consensus

among world leaders emerged in favor of reform, the details of the new system

likely would still be vulnerable to the various interests, constraints and

political whims of individual states. In the United States, for example, candy

makers hoping to extend daylight trick-or-treating hours on Halloween lobbied

extensively for the move of daylight saving time to November. According to

legend, in the Julian calendar, February was given just 28 days in order to

lengthen August and satisfy Augustus Caesar's vanity by making his namesake

month as long as Julius Caesar's July. The real story likely has more to do

with issues related to numerology, ancient traditions or the haphazard

evolution of an earlier Roman lunar calendar that only covered from around

March to December. Regardless of what exactly led to February's curious

composition, its diminutive design reinforces the complicated nature of

calendar adoption.

Such interference

would not necessarily happen today, but it matters that it could. The policy is

not made in a vacuum, and even the carefully calibrated Hanke-Henry calendar

would not be immune to politics, narrow interests or caprice. Given the opportunity

to bend such reform to a state's or leader's needs, even if only to prolong a

term in office, manipulate a statistic or prevent one's birthday from always

falling on a Tuesday, certain leaders could very well take it.

Calendrical change is

possible, it just tends to happen in fits and starts, lurching unevenly through

history as each era refines, tinkers and adds its own contributions to make a

better system. And if a global heavyweight with worldwide influence and leadership

capabilities adopts the change, others may follow, even if not immediately.

Nonetheless, a

fundamental, worldwide change to something as long-established as the calendar

is not unthinkable, primarily because it has happened several times before. In

other words, calendrical change is possible, it just tends to happen in fits

and starts, lurching unevenly through history as each era refines, tinkers and

adds its own contributions to make a better system. And if a global heavyweight

with worldwide influence and leadership capabilities adopts the change, others

may follow, even if not immediately.

For updates click homepage here