By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Muslim And Hindu, What's The Problem?

In particular, some videos show young Muslim

men being hit by a Hindu mob. And the cops are asking the fallen and beaten

Muslim men to sing the national anthem as they’re being pounded. That is quite

egregious.

But the more

significant evidence thus far is of the police simply looking away and not

responding to Muslim pleas for help as homes, places of worship, and commercial

enterprises were attacked with impunity.

This included that

one reporter was shot and survived, another had his teeth knocked out, and many

more said Hindus

demanded proof of religion and tried to keep them from documenting

vandalism and violence that included people attacking one another with axes,

swords, metal pipes, and guns.

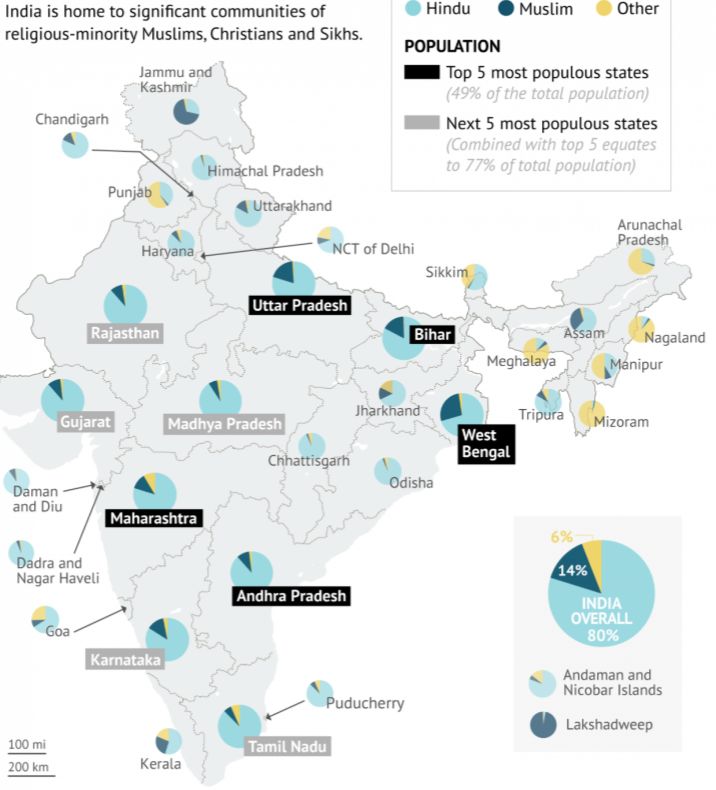

As a result, many of

India’s 200 million Muslims are reckoning with a future as second-class

citizens. In December, the BJP pushed through a new citizenship law that makes

it easier for all of South Asia’s major religions, except Islam, to gain asylum

in India. Shah, Modi’s Home Minster and de-facto deputy, hailed the law as

proof of the BJP’s commitment to helping refugees and said Muslims had nothing

to fear. But taken together with a separate BJP project to combat illegal

immigration, which would require all Indian citizens to prove their residency

with papers many do not have, critics see ominous signs. In Assam, a

northeastern state that has served

as a testing ground for the population register.

“Jai Shri Ram!” Those

were the words 25-year-old Kapil Gujjar shouted as he pointed his

semi-automatic pistol at hundreds of unarmed women and children at Shaheen

Bagh, a predominantly Muslim colony in New Delhi, on Saturday, Feb. 1. It was a

cool, smog-infused afternoon, and Indians from all walks of life had gathered

in a peaceful protest against a controversial new citizenship law that

especially affects the country’s poor, women,

and, perhaps most of all, Muslims.

Gujjar fired three bullets in the air. The crowd scattered. Later, while being

handcuffed by the police, Gujjar explained his motive: “In

our country, only Hindus will prevail.”

Jai Shri Ram

literally translates as “Victory to Lord Ram,” a popular Hindu deity. But while

this seemingly harmless phrase originated as a pious declaration of devotion in

India, it is today increasingly deployed not only as a Hindu chauvinist slogan

but also as a threat to anyone who dares to challenge Hindu supremacy.

Ever since Narendra Modi was reelected India is

changing. An example were the Shaheen

Bagh protests, to which The Guardian added: 'Modi

is afraid'. Similarly, demonstrations

have spread beyond India.

On Tuesday, Prime

Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party

suffered a major defeat in elections for the Delhi state legislature. The

election in Delhi was held while India has been witnessing continuous protests

against a citizenship law passed by Mr. Modi’s government in December that makes

religion the basis for citizenship. The new law discriminates against

Muslims and advances the Hindu nationalist agenda of reshaping India into a

majoritarian Hindu nation.

At a Delhi election

rally, Anurag Thakur, Mr. Shah’s colleague and India’s minister of state for

finance, raised

a sinister slogan: “These traitors of the nation! Shoot them!” A few days

later, two Hindu nationalist activists opened fire on students and protesters

at Jamia Millia Islamia and in Shaheen Bagh.

To interpret defeat

of Modi’s party in Delhi with his project of Hindu majoritarianism would be a

grave misreading of the verdict. In a recent survey,

four-fifths of Delhi’s voters favored Mr. Modi and three-fourths of Delhi’s

voters expressed satisfaction with his federal government.

Since its inception,

the Hindu nationalist movement, of which the B.J.P. is the electoral branch,

had a single goal: Hindu supremacy.

Another aspect in

this context of Modi's ideology that I will not expand on any further here has

to do with his belief and conviction of a 'reverse' Aryan migration theory, as

among others mentioned in Blood

nationalism: Why does Hindutva perceive a mortal danger from the Aryan

Migration Theory? And arguing that the so called Vedic culture was

developed by indigenous people of South Asia I earlier

covered here:

The context of what is happening in India.

While India’s Muslims

following the above mentioned New Delhi rally accuse

the police of targeted killings, if nothing else one can safely say that

the Narendra Modi Government’s anti-Muslim citizenship laws, seek to make life

as uncomfortable as possible for the country’s 200 million adherents of the

Islamic faith.

Also, for decades

India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party and its affiliates have struggled

to control one of India’s most fertile ideological recruiting grounds:

university campuses.

That project erupted

in violence last weekend, as masked men and women stormed

the New Delhi campus of Jawaharlal Nehru University, one of India’s premier

liberal institutions.

Witnesses said police

officers stood by as students were attacked with rods and bricks. Some

assailants shouted slogans associated with Modi’s governing party and its parent organization, the Rashtriya

Swayamsevak Sangh, or R.S.S., which for decades has aspired to turn India

into a Hindu nation.

Students and faculty

at the university said freedoms there had eroded since the election of Modi,

whose government has appointed

R.S.S.-affiliated administrators to the university. In the hours after

Sunday’s attack, staunch supporters of Modi’s party called for the university

to be closed.

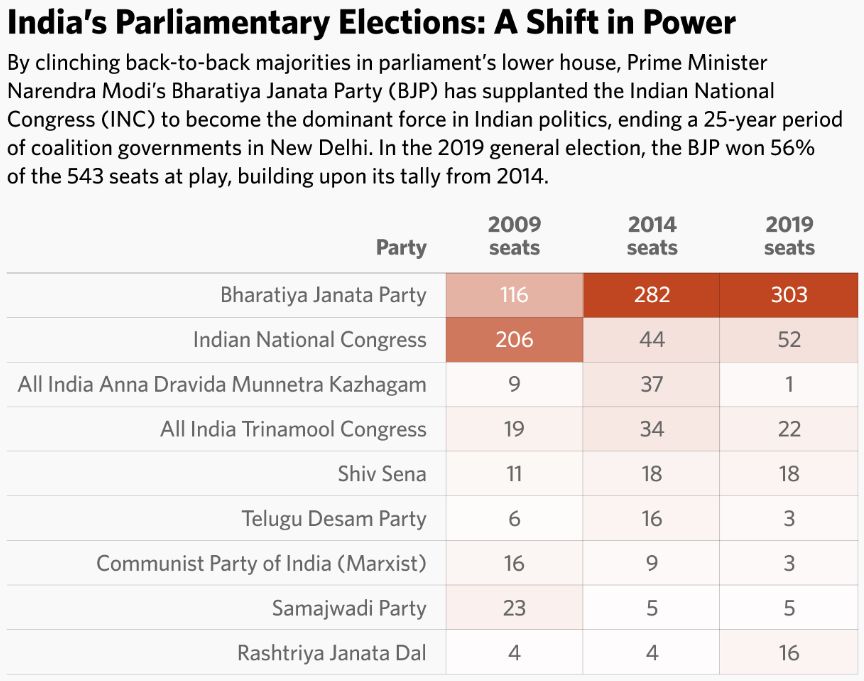

The current

vilification of supposed ‘foreigners’ fits with the nationalist politics of

India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the

subject of the country’s ‘illegals’ played a prominent part in the campaign for

the May 2019 elections, in which the BJP won nearly two-thirds of seats in

parliament. Addressing crowds in West Bengal in April, the home minister, Amit

Shah, pledged that a BJP government would "pick

up infiltrators one by one and throw them into the Bay of Bengal."

Since coming to power in 2014, the party, aided by the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya

Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) volunteer organization, which effectively serves as

a shadow state, has kept communal tensions at a steady simmer. At campaign

rallies and in media appearances it has fed a steady stream of rumor into

mainstream discourse.

With the gradual rise

of the BJP, particularly Muslims

are being marginalized politically and pushed out of public institutions

such as the police and the judiciary. Muslims hold just 4 percent of seats in

the outgoing parliament, down from a peak of 9.6 percent in 1980. During Modi’s

first term, expressions of anti-Muslim hatred have grown more common, and

acceptable, in public life.

One symptom of this

is a growing number of lynchings of Muslims

in relation to cows, animals considered sacred by orthodox Hindus. In

September 2015, a Muslim laborer, Mohammad Akhlaq, was murdered by his

neighbors in a village outside New Delhi on suspicion of eating beef.

Afterward, officials seized meat samples from the victim’s home to determine if

it was beef, which extremists argued would be a mitigating factor in his

killing.

Between May 2015 and

December 2018, at least 44 people, 36 of them Muslims, were killed across 12

Indian states. Over that same period, around

280 people were injured in over 100 different incidents across 20 states.

The attacks have been

led by so-called cow protection groups, many claiming to be affiliated to

militant Hindu groups that often have with ties to the BJP. Many Hindus

consider cows to be sacred and these groups have mushroomed all over the

country. Their victims are largely Muslim or from Dalit (formerly known as

“untouchables”) and Adivasi (indigenous) communities.

According to a survey

by New Delhi Television, there was a nearly 500 percent increase in the use of

communally divisive language in speeches by elected leaders, 90 percent of them

from the BJP, between 2014 and 2018, as compared to the five years before the

BJP came to power. Cow protection formed an important theme in a number of

these speeches.

Belonging to an umbrella led by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) underneath supporters of

the Vishva Hindu Parishad:

The BJP added a caste

approach to its Hindutva politics. In India, there are several parties whose

main support base is in the lower castes who are oppressed by the higher castes

and who demand some equity (such as reserved places in government jobs and educational

institutions). The BJP launched a demagogic attack on these parties on the

grounds that they have caste-biases, but at the same time appealing to those

castes that the caste-based parties have traditionally ignored.

The BJP also gave

political cover and recognition to brazenly communalist candidates associated

with the RSS and its affiliates, including some accused of terrorism. This was

done in order to valorize Hindu chauvinism and to suggest that violence against

non-Hindus is legitimate. They included one, Pratap Sarangi, who is the former

leader of a hardline right-wing group, the Bajrang Dal. Members of the group

were convicted of the brutal

murder of Australian Christian missionary Graham Staines and his two

children in 1999.

The road to a Hindu only nation

In their conception

of the nation, which was enshrined in India’s liberal constitution adopted in

1950 and set the tone of public life for decades after the end of colonial

rule, India should be a secular state that belongs equally to all members of

its complex multifaith society, whether from the large heterogeneous Hindu

majority or smaller communities that follow the Semitic religions of Islam and

Christianity, which have also flourished for centuries in the subcontinent. But

the militant Hindus who tore down the Babri Masjid, and their powerful

political patrons from the Bharatiya Janata Party

(BJP) and its parent organization the Rashtriya

Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), saw things differently.

Influenced by

Hindutva, a word that literally means Hindu-ness but has come to stand for the

Hindu nationalist political ideology, they believe that India belongs first and

foremost to Hindus.

The January 1948

assassination of Mahatma Gandhi by Nathuram Godse, a rightwing Hindu

nationalist who blamed Gandhi for capitulating to Muslim pressure and allowing

the partition of India to create Muslim-majority Pakistan, cast a long shadow

over the RSS, which was briefly banned and struggled for decades to regain

public legitimacy. But today, the debate is once again intensifying, as Prime

Minister Narendra Modi, a dedicated RSS activist

since his youth, won a second five-year mandate from India’s estimated 900

million eligible voters.

And to judge from the

results of the

election, the pluralist idea of India is receding

into the past. At the polls, 44 percent of Hindus, a larger proportion than

ever before, voted for the ruling Bharatiya Janata

Party (BJP), which seeks to transform India into

a Hindu nation. According to public opinion surveys conducted between 2016

and 2018 by researchers at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies and

Azim Premji University, a majority of Hindus, including those who vote for

other parties, now profess support for some of the BJP’s most important Hindu

nationalist positions. This was also the first Indian election in which no

major political party challenged the BJP’s position that India’s Hindu majority

constitutes a single community that can rightfully claim ownership of the

nation. Today, the basic struggle in Indian politics is not over whether Hindus

and Hinduism should enjoy privileged status but over the precise legal and

constitutional forms that privilege will take.

Seeing these developments in the context

In 1997, the

historian Sunil Khilnani described

"the idea of India,” usually attributed to the country’s first prime minister,

Jawaharlal Nehru, as an imagined secular, pluralist, polity that belonged to

all Indians and not to any one group. In particular, India did not belong to

the Hindu majority, which constituted 80 percent of the country’s population

according to the last official census. It was this secular idea that created

India in 1947, not as the Hindu mirror of a Muslim Pakistan, but as the

pluralist opposite of majoritarian nationalism.

Now, things have

changed. With the BJP’s rise to become India’s governing party, the idea of

India is being redefined to mean a Hindu polity. Through acts of violence as

well as words and laws, India is debating not whether the country’s political

system should recognize Hindu identity, but the precise way in which it should

be recognized.

The BJP, which has

for decades called upon the government to recognize the special rights of

Hindus in a Hindu majority country, has been the single most important force in

shifting the terms of the debate.

As a committed RSS man, Modi believes in turning

India into a theocratic Hindu state, where citizenship is defined on the basis

of being a Hindu.

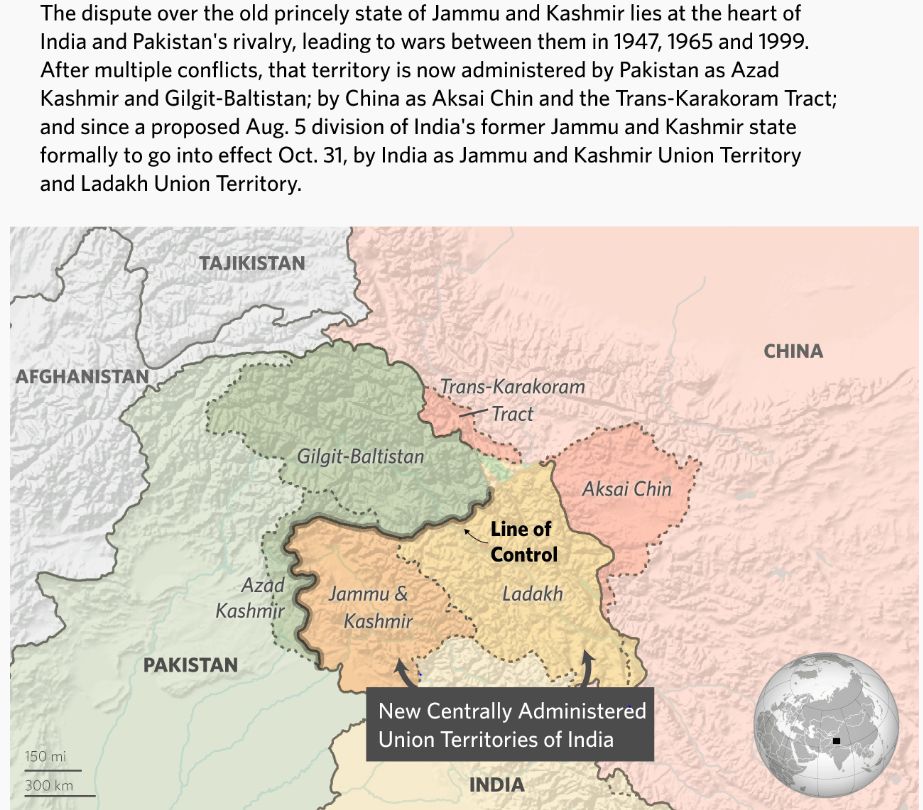

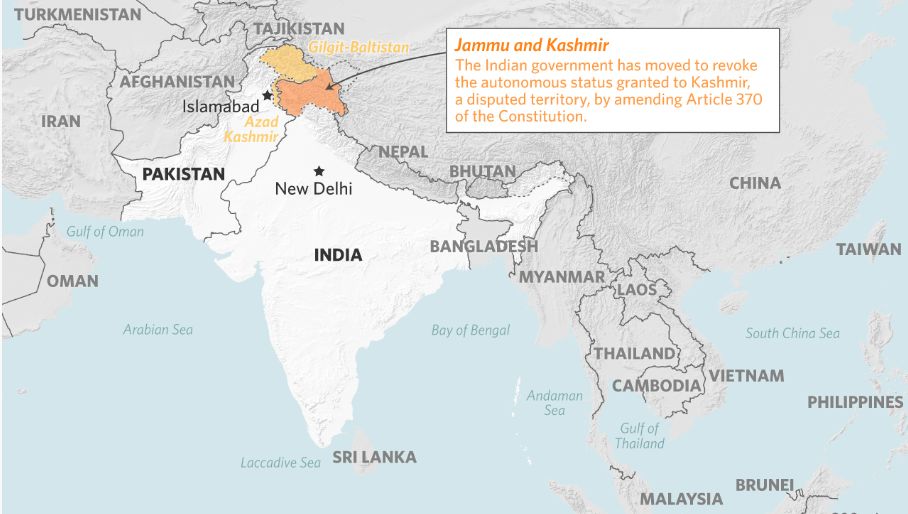

Thus after promises

on the campaign trail, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has come true to his

word, energizing his supporters and exasperating his opponents in equal

measure. On Aug. 5, Modi began a process to revoke

the special autonomous status of the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir,

igniting a political firestorm in New Delhi and, potentially, tensions with

nuclear archrival Pakistan. In line with Modi's directive, Indian President Ram

Nath Kovind issued a presidential decree supplanting the Indian Constitution's

Article 370, which grants Jammu and Kashmir autonomy in managing its internal

affairs with the exception of defense, foreign affairs, and communications.

What's more, the decree will also impact Article 35A, which restricts

non-Kashmiris from buying land in the state, potentially opening the way for

non-Kashmiris and Hindus to migrate to the state and alter its Muslim-majority

demographics.

Reflecting its Hindu

nationalism, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has renamed

Allahabad, a Hindu holy city bearing a distinctly Muslim name, with the

Hindu-inflected "Prayagarj." He has also

renamed the Faizabad district after one of its towns, Ayodhya, a locality in

which Hindu nationalists have demanded to construct a temple to Ram over the

ruins of the 16th-century Babri Mosque.

The idea that some

form of Hinduism should be recognized in some way by the Indian state resonates

among both the cosmopolitans and the dispossessed. What is at issue is how it

should be recognized. The BJP is the main political party addressing this concern.

Prominent leaders in the party and its parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), have offered four

proposals, all of which raise the crucial questions not just of what place

non-Hindus should have in India’s political system, but also of who counts as a

Hindu, and what counts as legitimate Hinduism. The label “Hindu” encompasses a

great range of communities, beliefs, practices, and languages. If Hinduism is

to be recognized by the state, whose Hinduism should it be?

Whose Hinduism?

The first argument on

offer holds that the Indian state should recognize Hinduism as at least

symbolically pre-eminent, while guaranteeing equal rights to all citizens,

including those from the many religious minorities. This first-among-equals

view calls for India to recognize Hindus in a way that is roughly comparable to

the way in which the United States recognizes Christians, for example: by

privileging Christmas as a national and official holiday while not privileging

the rights of Christians as a religious group.

This soft pro-Hindu

view, often found among those who have joined the BJP directly (that is, not by

way of the RSS or its affiliated organizations), challenges the above mentioned

Nehruvian idea of a state equidistant from all religions. That idea is currently

enshrined in law: the Indian state does not privilege Hindu religious holidays.

Government offices closed for the holidays of all major religious groups.

If the

first-among-equals view was to become law, it would not necessarily entail

inequality in legal or material rights and entitlements, but it would leave

non-Hindus lesser owners of their country in a symbolic sense. In addition, it

would place those Hindus who do not follow whichever branch of the religion the

state ended up recognized in the same position. If the state is going to mark

Hindu holidays, for instance, it would have to decide whether to privilege

Diwali (the biggest festival of the year for many north Indian Hindus), Durga

Puja (the major festival of Hindus in West Bengal), Ganesh Chaturthi (for those

in the west of India), or Onam (the major Hindu festival in Kerala). The

pluralist idea of India avoided this problem entirely.

The second argument,

call it majoritarianism, goes further. India, it holds, should adopt laws that

privilege its Hindu majority while giving non-Hindus diminished legal status.

This is the standard position the BJP and many of its leaders have articulated

over the last two decades. If majoritarianism were to prevail, India’s

non-Hindu minorities would become second-class citizens. Many Hindus might

become second-class citizens, as well.

To see this, consider

the BJP’s position that the Indian state should ban the slaughter of cows

because the cow is sacred to Hindus. This idea has assumed a new urgency

following a recent spate of lynchings

of those, as pointed out above mostly often Muslims, accused of killing cows.

Some senior BJP leaders have openly

backed the killings. But as with most beliefs associated with Hinduism,

some Hindus hold cows sacred and others don’t. There are many perfectly

traditional beef-eating Hindus, especially in southern and northeastern India.

It should be no surprise that many of those lynched for cow slaughter have been

Hindus. A rough count conducted by

the Hindustan Times of 50 cases of “cow-terrorism attacks” since 2010 in

which the identity of victims was discernible found that in at least one out of

every four cases, the victim was Hindu, including Dalits (mostly Hindu groups

who were once treated as untouchable). There are also many non-traditional

atheist Hindus who do not hold the cow sacred. A ban on cow slaughter would

discriminate against these Hindus and non-Hindus alike.

According to the

third argument, Hindus constitute not only a religious majority but also a

nation in themselves. This nationalist view has long been the position of the

RSS and of RSS traditionalists within the BJP. It is also the position

reflected in the Citizenship Amendment bill, a proposed law introduced by the

BJP in 2016 and now under consideration by parliament, which seeks to covertly

privilege Hinduism through amendments to India’s citizenship laws. This

position would demand the assimilation of India’s non-Hindu minorities and has

already been by used

by the RSS and its affiliates to justify forcing Muslims to convert to

Hinduism, a process euphemistically termed “ghar

wapsi” or “homecoming.” It would require the assimilation of many

Hindus, too, into whatever interpretation of Hinduism the state espouses.

Hinduism as a nation

The fourth argument

is the most extreme. Its proponents believe that not only should Hinduism form

the basis of the nation but India should be a theocratic state with religious

leadership. The BJP and the RSS are not sympathetic to this view. But in 1964,

as part of an effort to mobilize the Hindu majority, the RSS created the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, or “World Hindu Council,”

whose professed goal is to unite the Hindu clergy on a single ecclesiastical

platform. Although this is not part of the official platform, many in the VHP

espouse a theocratic idea of the Hindu nation and have now developed an

independent popular base. Last year, Modi appointed the religious leader and

VHP member Yogi Adityanath to be the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, India’s

most populous state. The selection demonstrated the degree of pressure that

this theocratic tendency and its constituency exert on the RSS and BJP.

Nationalism ascendant

Viewed along this

spectrum, Vajpayee, an advocate of the majoritarian view, was no moderate. He

sought to privilege Hindus over other religious groups, in a radical departure

from India’s founding ideology. Only the emergence of even more extreme versions

of Hindu nationalism allowed Vajpayee’s position to come across as

middle-of-the-road.

Take Vajpayee’s

reaction in 1992, when a mob aligned with the BJP destroyed

a sixteenth-century mosque in the town of Ayodhya, in North India. The BJP had

previously campaigned to replace it with a Hindu temple. Unlike some BJP

leaders, Vajpayee was not present at the demolition and apologized in the days

that followed. But he apologized only for the spontaneous and uncontrolled

destruction of the mosque, not for the original position that a temple should

replace the mosque. He had always supported that view and made

a speech saying as much just the day before the mosque was demolished.

Vajpayee’s

“moderation,” such as it was, came from his personality and his love of poetry,

which often overcame his ideology. He had a large heart, a poet’s eloquence,

and a poet’s indiscipline in sticking purely to ideological matters. These

traits helped him build and sustain relationships across ideological lines.

They also allowed him to connect instantly with a crowd. For example he told

stories of the Emergency imposed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi between 1975

and 1977, during which many opposition leaders were jailed. Vajpayee had been

one of them, and he spoke of undergoing surgery in prison that had permanently

injured his back. “Now,” he said, “I am incapable of genuflection, even if Mrs.

Gandhi were to order me to bow before her.” The crowd roared with laughter.

They liked and respected him. But eloquence and an affable personal style do

not add up to ideological moderation. Vajpayee’s words and actions often

transcended ideology. But when he did take an ideological position, it was

unswervingly majoritarian.

Vajpayee’s lack of

moderation does not mean that there is no moderate way of responding to the

search for a Hindu identity in the symbols of the state. The pluralist idea of

India that Sunil Khilnani wrote about contains the ingredients for such a

moderate response since it offers equal respect not only to India’s non-Hindu

minorities but also to the many different ways of being Hindu. And that

"Constitutional democracy based on universal suffrage did not emerge from

popular pressures for it within Indian society."

But Nehru’s

successors gave up on that pluralist idea long ago. His daughter, Indira,

stoked the anxieties of the Hindu majority in her election campaigns in the

early 1980s. His grandson Rajiv Gandhi courted the Hindu majority by launching

his 1989 election campaign from the town of Ayodhya and calling for “Ram

Rajya,” the rule of Lord Ram. Now, his great-grandson Rahul Gandhi, the current

leader of the Congress Party, has begun to flash his own pro-Hindu credentials.

During regional elections last year, he made

conspicuous visits to temples. In September, in anticipation of the 2019

parliamentary elections, he set

off on a pilgrimage to Mount Kailash in Tibet, which many Hindus consider

to be the home of the deity Shiva. On the way, he tweeted that “Shiva is the

universe,” and published Fitbit data showing each of his steps along the

pilgrimage route, turning what could have been a private visit into a political

spectacle. Days later, the Congress party put up election-related

posters declaring Gandhi a devotee of Shiva. This half-hearted attempt at

beating the BJP at its own game ensures that some form of Hindu majoritarianism

will win in India’s 2019 parliamentary elections, no matter who loses.

Kashmir and the International aspect

the BJP yoked its

Hindutva agenda to its nationalist (mainly, anti-Pakistan) agenda. The impact

of nationalism and Hindutva peddled separately would be less than when they are

made to work in their mutual interaction. The BJP’s portrayal of Pakistan as the

mortal enemy is related to the perceived loyalty of Indian Muslims to Pakistan:

Pakistan was used as a euphemism for Indian Muslims.

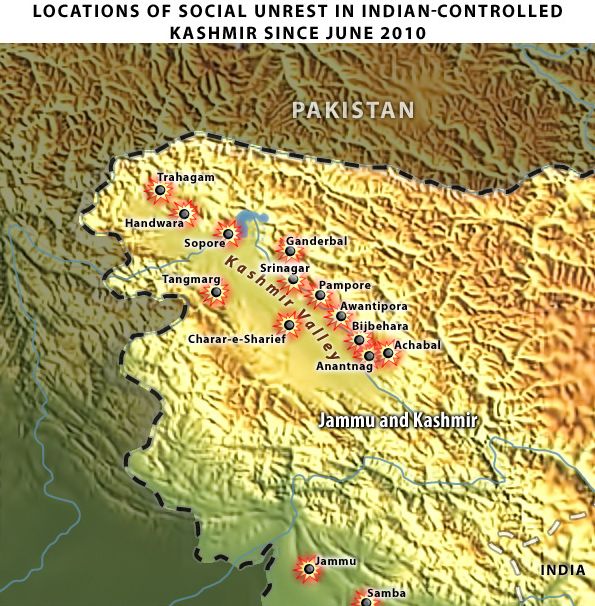

It is also to be

expected that during the rest of 2020,

Narendra Modi will tighten the central government's control over Kashmir by

enforcing a counterinsurgency campaign to keep violence manageable while

encouraging the migration of non-Kashmiri Hindus into the region and drawing

investment from outside the state.

After promises on the

campaign trail, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has come true to his word,

energizing his supporters and exasperating his opponents in equal measure. On

Aug. 5, Modi began a process to revoke the

special autonomous status of the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir,

igniting a political firestorm in New Delhi and, potentially, tensions with

nuclear archrival Pakistan. In line with Modi's directive, Indian President Ram

Nath Kovind issued a presidential decree supplanting the Indian Constitution's

Article 370, which grants Jammu and Kashmir autonomy in managing its internal

affairs with the exception of defense, foreign affairs, and communications.

What's more, the decree will also impact Article 35A, which restricts

non-Kashmiris from buying land in the state, potentially opening the way for

non-Kashmiris and Hindus to migrate to the state and alter its Muslim-majority

demographics.

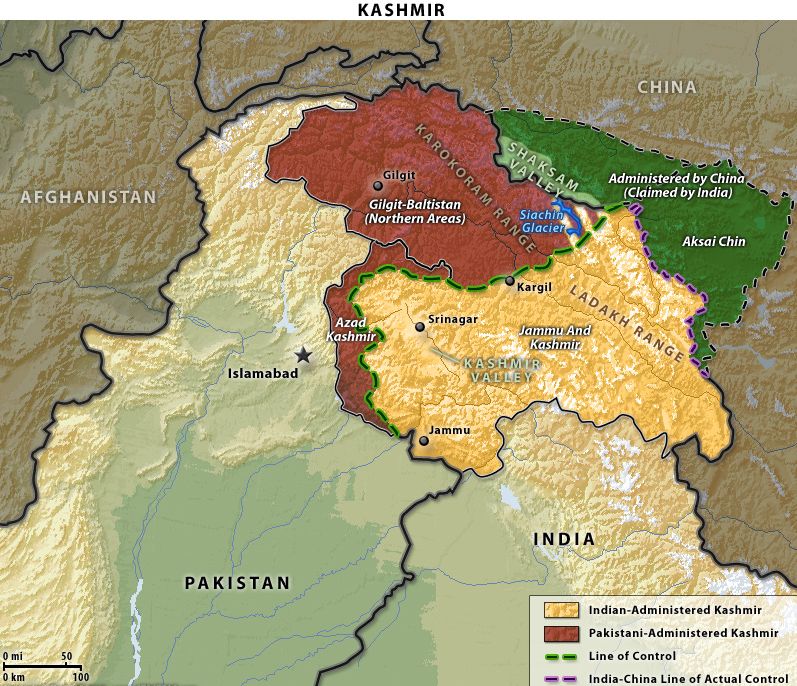

The Kashmir dispute

furthermore contains overlapping domestic and international components.

Domestically, it highlights the tension between the central government in New

Delhi, which is trying to assert its authority over a peripheral state that

harbors a deeply ingrained culture of autonomy that predates independence in

1947. India's only Muslim-majority state, Kashmir's special constitutional

status under Article 370 has always been a point of contention for the BJP,

whose Hindu nationalist base has agitated for the state's greater integration

with the country.

Kashmir thus also

lies at the heart of India and Pakistan's decades-old rivalry. Each country

governs the state in part but claims it in full. Following the independence of

both countries from the United Kingdom in 1947, Kashmir's then-Hindu ruler

ultimately joined India in exchange for military protection against a

Pakistan-backed domestic uprising aimed at wresting control over the state.

What began as a proxy conflict soon morphed into the first of India and

Pakistan's three wars over the territory. Today, Pakistan administers two

regions (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan), India three (Jammu, Ladakh and,

Kashmir) and China two (Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract). Pakistan

claimed Kashmir on the grounds that its Muslim-majority population justified

its inclusion in Pakistan, the homeland for the Muslims of British India.

India, however, argued that a Muslim-majority state was at home in the new

country's secular framework, which sanctioned no official state religion in

spite of the country's Hindu majority. Then there's the strategic aspect of the

countries' conflict over Kashmir, as the territory, which borders China,

Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Punjab provides the Indian Armed Forces with

a critical staging ground in any potential conflict

against China or Pakistan, India's two most serious rivals. At the same

time, Kashmir also has added importance for Pakistan, as the country's key

waterways, run through the state.

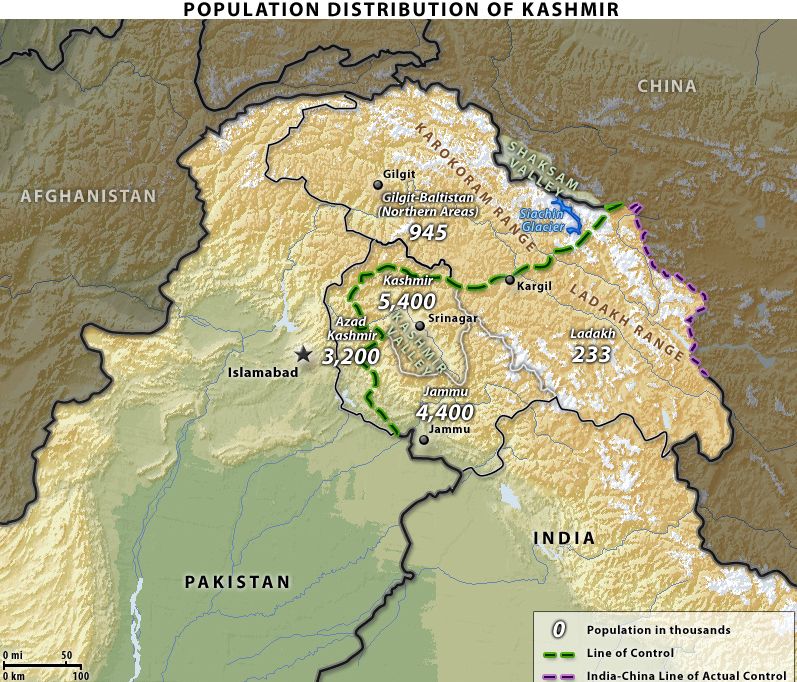

For people today who forget

that ‘map is not the territory’, it is easy to see why Kashmir is typically

understood as a territorial dispute between two belligerent neighbors in South

Asia.

Jammu and Kashmir is

a former princely state partitioned since 1949, yet still regarded as a

homogeneous entity. India and Pakistan control almost half of its territory a

small portion is occupied by China), with both claiming jurisdiction over the

whole. The line of demarcation is called the Line of Control. Nevertheless,

developments in the Pakistani part (made up of Azad Kashmir and the Northern

Areas) simply do not figure in the debates on Kashmir, while stories of

Kashmiris seeking to break away from the part administered by India distort

reality by overlooking the region's complexities. The political construct of a

Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir state pitted against a majoritarian Hindu

India-or of an Islamic bond cementing the relationship between Azad Kashmir and

the Northern Areas with Pakistan-is, at best, misleading.

Since 1989, the state

has witnessed an insurgency tacitly backed by Pakistan that seeks to separate

Kashmir from the union. In February, a militant belonging to one such

Pakistan-based group, Jaish-e-Mohammad, rammed a truck packed with explosives

into an Indian security convoy, killing 44. That attack prompted India to

retaliate against Pakistan by sending warplanes into undisputed Pakistani

territory to hit a militant training camp, a shift in India's military strategy

that involves striking deeper into Pakistan territory, both to exploit gaps in

its air defense and to heighten the costs for Islamabad with the aim of

deterring future cross-border attacks. Pakistan responded with its own

airstrikes the next day. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan's release of a

captured Indian pilot gave both countries an off-ramp, but the BJP used the

incident to prioritize national security in the run-up to the general elections

that began in April. Khan, who chaired a National Security Council meeting over

the weekend prior to the 5 Aug. announcement, has called the Modi government's

decision "illegal," while the Pakistani National Assembly will hold a

joint session of parliament on 6 Aug., though this was a largely symbolic

gesture aimed at drawing attention to the Indian announcement.

Going forward, a

variety of factors are likely to be in play, including possible troop movements

and new cease-fire violations between the Indian and Pakistani militaries along

the Line of Control, the de facto border separating the region. The great powers,

too, might take an interest in the issue. U.S. President Trump has already

offered twice to mediate on Kashmir while China could also become involved

given that it is Pakistan's strongest ally, but also a country that wants to

maintain calm relations with India. Of perhaps greatest concern, however, is

the question of how Kashmir's militants will respond to the decision. If New

Delhi experiences another attack that it blames on militants from over the

border, has recently accused Islamabad of disrupting the peace by laying

landmines to target Hindu pilgrims, it could call for an even more forceful

response against Pakistan. That, naturally, would bring the subcontinent's

nuclear-armed rivals closer to the edge of a conflict that would reverberate

far beyond disputed Kashmir.

The BJP-led

government's attempt to bring Kashmir closer into the fold ultimately fits into

its broader project to solidify the political and economic unity of India, a

country of 1.3 billion people whose immense linguistic, cultural and

demographic diversity has meant its states resemble countries in their own

right. Nevertheless, legal challenges, possibly involving the Supreme Court,

could yet hamper the government's efforts in Kashmir, while opposition

politicians will seize on the opportunity to chastise the government on

amending the constitution without encouraging a democratic debate.

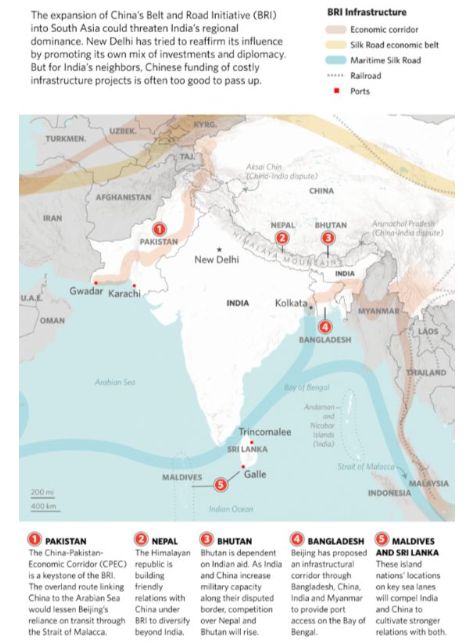

Foreign policy going forward

Finally India's fears

of Chinese strategic encirclement will accelerate its investment and defense

overtures to neighboring countries in South Asia, marking a central plank of

Modi's foreign policy in 2020. However, Beijing's funding advantages over New Delhi

and its willingness to renegotiate debt with Sri Lanka and the Maldives explain

why its political and economic relationships with these countries, as well as

with Nepal and Bangladesh , will only grow, particularly as the countries wish

to diversify their foreign relations beyond India, the regional hegemon.

For updates click homepage here