The impeachment of the first

governor-general of Bengal

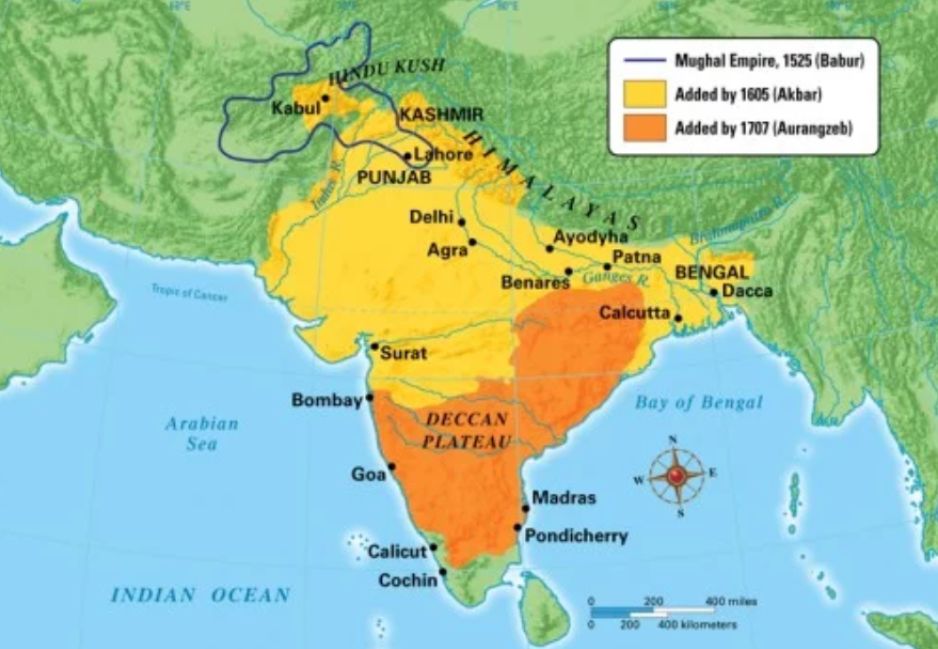

The decay of the

Mughal Empire was bad for business, and as parts of the interior descended into

civil war and chaos, the trading companies dotted around India became concerned

for their profits. At the same time, rapid advances

in Western military tactics and technology began to offer even small

detachments of European soldiers decisive advantages over local troops.

But it was initially

Vasco da Gama who hired an Indian navigator in Kenya that brought them on a

journey from the east coast of Africa to what is now Kozhikode in what is now

the south Indian state of Kerala. This then led six years to the "Portuguese

State of India" with its headquarters in what is now the state of Kerala.

And in the face of encroachments by other European powers was later followed by

the Portuguese East India Company with the purpose of scotching the menace of

French (la Compagnie des Indes) including the relevant Dutch and English

companies.

Not of little

importance was that at the height of the Mughal empire in the seventeenth

century, cash and credit, a wide range of goods, and

even people circulated on a much larger scale than in earlier times.

Of even more

significance was the impact of European firearms.

The rise of Robert Clive

Matters came to a

head in 1744 with the declaration of war in Europe between England and France.

The French, led by the energetic Joseph-François Dupleix, governor-general of

all French possessions in India, seized Madras from the British on October 1746,

only to return it in 1748 under the terms of the Aix-la-Chapelle treaty. One of

the English defenders of Madras who became a prisoner of the French was Robert Clive, a young copywriter in the service of the

British East India Company and who would later become its most successful

defender.

Then when in 1756 the

Seven Years War broke out in Europe, the French renewed their efforts against

the British in India under Thomas-Arthur de Lally, who had been sent to India

in 1758. Unfortunately for the French, Lally’s campaigns were a series of

disasters and blunders. His first mistake was to recall Gen. Charles de usy from Hyderabad just when the general had all but taken

over this powerful kingdom.

While the British

fought the French in southern India, they also carried out a protracted

campaign in Bengal to expand their territories and influence. Thus in the 17th

century, the English East India Company had been given a grant of the town of Calcutta by the Mughal Prince Shah Shuja. At

this time the Company was effectively another tributary power of the Mughal.

Bengal was a province

of the Mughal Empire, and an appointed military governor, or faujdar, oversaw

its administration. After the fall of the Mughal Empire the Nawab of Bengal,

Ali Vardi Khan (who had toppled the Nasiri Dynasty) broke away from Delhi’s weak

control in 1742. He ruled until his death in 1756, after which his son Siraj-ud-Daulah succeeded him. Both father and son maintained

extremely rigid control of the Europeans at the trading posts in Bengal. The

British, who had the largest presence in the region, however, resented this

control and on 1752 Robert Orme, in a letter to Robert Clive, noted that the company would

have to remove Ali Vardi Khan in order to prosper.

Once the Treaty of

Allahabad was signed on 12 August 1765, between the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam

II, son of the late Emperor Alamgir II, and Robert Clive, of the East India

Company, as a result of the Battle of Buxar of 22 October 1764, the East India

Company next started to collect taxes.

Underneath,

the Mughal emperor Shah Alam hands a scroll to Robert Clive, the governor of

Bengal, which transferred tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to

the East India Company. Illustration: Benjamin West (1738–1820)/British Library

When money took over

The collecting of

Mughal taxes was subcontracted to a multinational corporation whose operations

were protected by its own private army. Within a few months, 250 company clerks

backed by a force of 20,000 locally recruited Indian soldiers had become the effective

rulers of the richest Mughal provinces. An international corporation was, for

the first time, transforming itself into an aggressive colonial power.

Before long “the Company” was straddling the globe.

The ferried opium

east to China, and in due course fought the Opium Wars in order to seize an

offshore base at Hong Kong and safeguard its profitable monopoly in narcotics.

To the West it

shipped Chinese tea to Massachusetts, where its dumping in Boston harbor

triggered the American War of Independence.

And while thus the

company under Clive transformed itself from a modest trading venture into a

powerful corporate machine as Philip Francis, one of its leading critics, put

it, instead of seeking “moderate but permanent profit”, the company had

recklessly pursued “immediate and excessive returns”.

During the first

century of the East India Company’s expansion in India, most people in India

lived under regional kings or Nawabs. By the late 18th century many

Moghuls were weak in comparison to the rapidly expanding Company as it took over

cities and land, built railways, roads, and bridges. The first railway of 33.8

km, known as the Great

Indian Peninsula Railway ran between Bombay (Mumbai) and Tannah (Thane) in

1849.

Researching the Bengal famine

While it is true that

famines where common in India already before the British arrived there to

date, there has been an ongoing discussion (where Robert Clive is often

described as a psychopath) about the coming about of the private East India Company on 22

September 1599 whereby then when in the ensuing decades numeral complaints were

logged (many of these also because it was seen as if the "company"

did not enough to prevent the famines) "the Company" then lost all

its administrative powers following the Government of India Act of 1858. Here

the provisions called for the complete liquidation of the British East India

Company and the transference of its functions to the British Crown.

Questions about how,

and why, "the company" turned into an empire have recently become historical

battlefields, with traditionalists insisting that the indigenous Mughal

Empire’s decay forced the company to take up arms to restore order, while those

on the left respond that the company created the chaos that it exploited.

Making war, he argues, was rarely the company’s only option, yet it really did

have violent enemies, and the French really were plotting against it.

Similarly, the company’s men were often wicked and arrogant; they bribed,

robbed and killed those who crossed them, even their Indian opponents could

commit even more appalling acts of violence.

While it was only

later (it took 6 weeks to travel from to India at the time meaning letters took

accordingly) that word would start to spread about Bengal's famine, already on on 22 January 1770 former Prime Minister William Pitt in

his state of the nation at the House of Lords felt compelled to

say that: "The riches of Asia

have been poured in upon us," he declared at the despatch

box, "and have brought with them not only Asiatic luxury, but, I fear,

Asiatic principles of government. Without connections, without any natural

interest in the soil, the importers of foreign gold have forced their way into

Parliament by such a torrent of private corruptions as no private hereditary

fortune could resist."

Pioneering work in

this field has been done by Richard Eaton who, in his study of the Bengal

frontier, argues that the provincial Mughal officials deepened the roots of

their authority in the countryside through encouraging intensive wet rice

cultivation at a time when the Mughal power in Delhi was steadily diminishing.

This patronage system, introduced by the Nawabs, which had played a decisive

role in the steady growth of food grains, ended in 1760 with the paramountcy of

the East India Company in the Bengal region.1

Rajat Datta's,

Society, Economy and the Market: Commercialisation in

Rural Bengal, c1760– 1800 (chapter five, pp. 238– 84) in turn argued that while

military conquests, political dislocations, and Company exactions certainly

contributed to the vulnerability of peasants, there had been a major shift in

agriculture and the economy under the Company which contributed to the

intensity of the famine. Bengal’s prosperity was vulnerable and ecologically it

was undergoing major changes. The flow of the rivers was moving eastward and

cultivation was spreading eastward too. While the west of Bengal was drying

out, which made it desperately vulnerable to famine if the rains failed, the

east was flourishing. It escaped the 1769–70 famine, although as Datta shows,

flooding was to devastate it later. Bengal had witnessed a long intensification

of wet rice cultivation under the Nawabs. This was a long-drawn-out process of

ecological transformation whereby the eastern Bengal delta constituted an

agrarian frontier where provincial Mughal officials had directly encouraged

forest clearing, water control and wet rice cultivation from the later

sixteenth century up to the middle of the eighteenth century.2

Rajat Datta, rejects

the widely quoted figure given by Warren Hastings (who was in London at the

time). He instead has shown that while the famine was at its worst in West

Bengal, and that large parts of Eastern Bengal were unaffected, 76,000 died in

Calcutta between July and September. "The whole province looked like a

charnel house," reported one officer. The total numbers are disputed, but

in all perhaps 1.2 million, one in five Bengalis starved to death in what

became one of the greatest tragedies of the province’s history.

Datta’s account

emphasizes the expansion of the regional market in grains which may have made

peasants more exposed to price shocks. He also makes an important point about

the geographical imbalance of the famine, which he believes was more severe in

western Bengal and Bihar and practically non-existent in eastern Bengal. The

veteran historian Peter

Marshall largely agrees with Datta’s account.

The territory of the

famine included what today would be West Bengal, Bangladesh, and parts of Assam, Odisha, Bihar, and Jharkhand.

Rajat Datta is skeptical

of the decisive influence of the British, let alone of specific individuals, on

the fortunes of the province. There, of course, can be no doubt that Bengal was

potentially a highly fertile and productive province. It had developed a

sophisticated commercialized economy … The British stimulated commercialization

by the growth of their export trades and of the great conurbation at Calcutta.

Did their access to political power have adverse effects? Probably. They may

well have taxed more severely, even if they had no capacity to extract directly

from the mass of peasants. They regulated some trades, such as high-quality

textiles or salt, to their own advantage and to the disadvantage of indigenous

merchants and artisans, but the huge grain trade was surely beyond their

capacity to interfere insignificantly. On the whole, there is serious doubt

whether the British either “caused” the famine or if one could credit

Hastings with the recovery of Bengal since it was neither or any other

British individual’s capacity to bring about such a thing.

These are clearly

complicated matters, involving ecological as well as economic history, and the

jury remains out. However, whether or not the Company was directly responsible

for the famine, or whether ecological factors played a more important role, its

incompetent response made the famine in West Bengal much more deadly, while its

excessive tax collecting hugely exacerbated the sufferings of the Bengalis

under its rule, which was certainly the opinion of many observers, both Indian

and British, who wrote accounts of the disaster at the time.

As W.

W. Hunter mentioned in The Annals of Rural Bengal also some Company

officials did their best to help the starving. In several places, the hoarding

and export of rice were successfully prevented. In Murshidabad, the Resident,

Richard Becher, ‘opened six centers for the free distribution of rice and other

supplies’. He also warned

the Calcutta Council about the dire consequences of failing to provide for the

starving and noted that the normally peaceful highways had become unsafe

and that highway robberies, once unknown, were now occurring every day as the

desperate and needy struggled to find ways to survive. The latter also mentions

that; "The biggest cause of death by famine was not the absence of grain

but inflation, a rapid increase of the price of rice."

The Governor of

Calcutta, John Cartier, also worked hard to alleviate the distress in the

Company’s capital: he maintained ‘a magazine of grain with which they fed

fifteen thousand every day for some months, and yet even this could not prevent

many thousands dying of want. The streets were crowded with the most miserable

objects, and there were 150 dead bodies picked up in a day, and thrown into the

river.

But in many of the

worst affected areas, Company efforts to alleviate the famine were

contemptible. In Rangpur, the senior EIC officer, John Grose, could only bring

himself daily to distribute Rs5 (81 $ today) of rice to the poor, even though

‘half the laboring and working people’ had died by June 1770 and the entire

area as Rajat Datta described was being reduced to graveyard silence.

The famine was a

severe humanitarian catastrophe and an ugly blot on Britain’s colonial record.

Scottish economist Adam Smith, a severe critic of colonial greed and the East

India Company, believed that it would have been no more than a manageable

food-shortage had

the Company pursued a policy of free trade.

Although it has no

exact equivalents, the Company was the ultimate prototype for many of today’s

corporations. The most powerful among them these days do not need their own

armies: They can rely on governments to protect their interests and bail them

out.

As Baron Thurlow

remarked in the late 1700s, when the Company was being criticized for its

misdeeds and its governor-general, Warren

Hastings the head of the Supreme Council of Bengal was on trial, “Corporations

have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned. They therefore

do as they like.”

Edmund Burke, the

English Demosthenes, charged Hastings at the bar of the House of Lords on the

tyranny and misdemeanor and also in the name of humanity, the English nation,

and the Indians and called him an enemy of humanity. He in his inimitable style

and rehetoric said in conclusion of his charge, “Therefore,

hath it with all confidence being ordered, by the Commons of Great Britain,

that I impeach Warren Hastings of high crimes and misdemeanours.

I impeach him in name of the Commons’ House of Parliament whose trust he has

betrayed. I impeach him in the name of the people of India, their right he has

trodden under foot, and whose country he has turned into a desert. Lastly, I

impeach him in the name of human nature itself, in the name of both sexes, in

the name of every age, in the name of every rank. I impeach the common enemy

and oppressor of all.”

As the first

governor-general of Bengal, Hastings was responsible for consolidating British

control over the first major Indian province to be conquered. In his term of

office, he initiated solutions to such problems as how vast Indian populations

were to be administered by a handful of foreigners and how the British, now

themselves a major Indian power, were to fit into the state system of

18th-century India. These solutions were to have a profound influence on

Britain’s future role in India. Hastings’s career is also of importance in

raising for the British public at home other problems created by their new

Indian empire, problems of the degree of control to be exercised over

Englishmen in India and of the standards of integrity and fair dealing to be expected

from them, and the solutions to these problems were also important for the

future.

Warren Hastings

survived his impeachment, but parliament did finally remove the East India

Company from power following the great Indian Uprising of 1857, some 90 years

after the granting of the Diwani and 60 years after Hastings’s own trial. On 10

May 1857, the East India Company’s security forces rose

up against their employer and on successfully crushing the insurgency,

after nine uncertain months, the company distinguished itself for a final time

by hanging and murdering tens of thousands of suspected rebels in the bazaar

towns that lined the Ganges, probably the most bloody

episode in the entire history of British colonialism.

The corporation, the

idea of a single integrated business organization stretching out across the

seas, was a revolutionary European invention contemporaneous with the

beginnings of European colonialism that upended the trading world of Asia and

Europe, and which helped give Europe its competitive edge.

Continued in part

two.

1) See Richard M.

Eaton, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier 1204–1760, Berkeley, 1993, p.

5.

2) On this see also

J. F. Richards, The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early

Modern World, Berkeley, 2003, p. 33.

For updates click homepage here