By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Japan And China

Contemporary Japan

faces a thorny series of difficulties, most of which are disturbingly similar to

(the by us earlier described) Japan’s late-nineteenth-century concerns. What

Japan cares about are in two regions the Western Hemisphere and Southeast Asia,

with only one itty-bitty problem: Japans dealing with

China.

It has become

conventional to study Japanese modernization starting with the Meiji period.

The Meiji reforms are often considered as the watershed in Japanese history, a

period of transition from feudal and traditional society to a modern

nation-state. In contrast, the Tokugawa era is often described as premodern,

feudal, and stagnant. Unlike the conventional approach that sees this period as

premodern ''tom by revolts, factionalism, and civil war," there is now a

growing tendency to consider the Tokugawa regime a modern sovereign state even

if it did not strictly coincide with characteristics of the Eurocentric notion

of modernity.

The Tokugawa period

is generally credited that it brought, to Japan social stability, economic

growth, urban culture, and a remarkable rise in literacy.s

However, the system came to the end of its glory after two and a half centuries

partly because of the changing nature of the Japanese economy and the

demographic pressures on the hierarchical social system. As a result of the

deteriorating financial situation, the samurai became poorer, the merchants (shonin) increasingly became richer arid more powerful, and

the peasant class had to carry the entire burden of the deteriorating financial

situation.

The Japanese emperor

was little more than a figurehead with a dusting of religious connotations.

Real authority rested with his military commander: the shogun. Unfortunately

for the shogun and the emperor, “imperial” power rarely reached much beyond the

tips of their troops’ weapons. Rather than think of the shogun as all-powerful,

it is more accurate to consider him the most powerful daimyo.

The Daimyo and the

samurai, however, came to be in deep debt to increasingly powerful merchant

families like the Mitsui family in Osaka, who played an important role in the

overthrow of the Tokugawa regime. Under

these circumstances, the regime had to confront increasingly serious rural and

urban revolts. Amidst these economic and social problems, Western cultural,

economic, and military pressures to infiltrate Japan became increasingly

intense.

Contact with Europe

came quite late and initially was limited to a single port, Nagasaki, and a

single external partner, the Netherlands.

The Tokugawa however

perceived such attempts by the Westerners as a serious national security threat

and responded to them harshly. From the very beginning, the Tokugawa regime had

followed a closed country (sakoku) policy. They

expelled the Spanish in 1624 and the Portuguese in 1638. In 1637, the Japanese

were forbidden to leave their country without permission from the central

government.

In 1640, an edict was

issued to expel all foreigners from Japan except for a small trading station in

Nagasaki where the Dutch and Chinese were allowed to have limited residency and

trading rights. Many contemporary Japanese scholars believe that this policy of

seclusion created an isolationist mentality combined with a strong sense of

exclusionism and parochialism that continue to influence present-day Japanese

foreign policy.

But politically, this

enabled the Japanese to focus their efforts on unification, bit by bit at their

own pace. Strategically, the inward-focused obsession made the Japanese

maritime people without a navy.

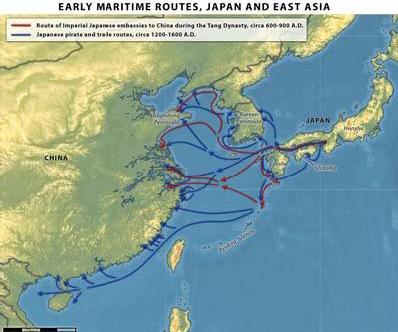

The subsequent

Japanese “navy” reflected the disunity, and sea-facing daimyos each fielded

their own forces of militarized junks. No individual daimyo could boast a large

enough naval force to sustain a trade route (much less a mainland Asian colony)

while still defending his territory back home, so Japanese interaction with the

wider world was far more adversarial and far less disciplined than that of

other naval powers. Not so many fleets, as mobs on water. Less imperialism,

more piracy. And yet Japan as a nation was forged in and by this naval chaos.

In 1800, roughly a

millennium after the Japanese cultural emergence, all of coastal Japan finally

was at least nominally under a single government, the Tokugawa Shogunate. But

before the Japanese could explore what that meant, the world rudely intruded into

their affairs. Thus Whether the Japanese liked it or not, modernity had

arrived, at gunpoint, no less.

With his black ships

behind him, when Commodore Matthew Perry of the

United States came to Japan in 1853, he was able to force the regime to

abandon its seclusion policy. The Tokugawa officials Were shocked by the power

of Perry's fleet and seriously discussed ways to tackle this challenge. Japan

was divided into opposing views about ways to confront the foreigners: some

advocated the continuation of the policy of sakoku

(national seclusion), which found its expression in the famous slogan, jo-i (expel the barbarians), whereas others supported the

policy of kaikoku (national opening). For instance,

Sakuma Shoza (1811-1864), a nationalist samurai from

central Japan trained in the Dutch School tradition, understood that China was

defeated because of its inflated feeling of superiority to other civilizations

that led to their neglect of Western science and mathematics. As he noted, in

order not to repeat the Chinese mistake, Japan had to open itself and learn

from the West.

Not to mention that

shortly after Perry’s visit, the British, French, Dutch, and Russians demanded

similar concessions. In a mere fifteen years, the sudden introduction of the

outside trade and the industrial technologies that went with them shredded Japanese

social, political, and economic norms, which had yet to fully absorb the

consequences of Japan’s own unification.

It was a race for the

control of East Asia and the dominance of the region through treaties,

influence, coaling stations, and steam. A race against Britain and Russia. For

Americans, the race was on. In the late 1 840s, American newspapers, magazines,

and journals began a systematic campaign reflective of the American sentiment

to throw open Japan to the commerce of the world. A debate about the US

relationship to Japan arose in all comers of the nation and was taken up again

and again in the country's largest papers. And once the US government had sent

a squadron to the Japan seas to request and negotiate a treaty, the domestic

press followed events closely. The Farmers' Cabinet journal put it in a

front-page article in 1849 entitled "Japan":

"Public attention is now turned towards the empire

of Japan, which has so long remained a sealed book in the history of the world."

The result was a fundamentally different kind of empire. In part, the

difference was because the rationale was different.

As recently as 1800,

Japan was the only local power that had any semblance of unity, and after

Japan’s forced opening to the world, it was the only local power with

steamships and firearms. Unity enabled the country to take full advantage of

the new industrial technologies, and Japan instantly became the dominant

regional power. In part, the difference was about imperial competition, or the

lack thereof.

Once the Japanese

mastered the making of cannons, the Europeans simply could not compete

effectively so far from home. Even the Americans left. Not long after Perry

invited himself into Japan with all the subtlety of a mafia protection

salesman, the Confederate Army was bombarding Fort Sumter and Yankee's

attention turned elsewhere. In part, the difference was about the speed of

Japan’s naval rise.

Less than twenty

years after the Perry expedition, Japan had upgraded from junks to

steam-powered destroyers. In 1894–95, Japan easily trounced the Chinese up and

down the East Asian coast in the Sino-Japanese War. In 1904–5, Japan conquered

all of Korea while also sinking the entirety of both Russian fleets in the

Russo-Japanese War.

But It wasn’t enough

for the country to import and use the new technologies; its cities were too

crammed to be competitive with the lower Age. Japan had to not only master the

technologies but also advance them. Politically and culturally, the general population

got swept up in the same modernizing, industrializing, nationalistic mindset

that had overtaken Japan’s new, modernizing elite and their corporate

expressions, the new zaibatsu (“money-cliques”). Strategically and militarily,

Japan’s newfound and rapidly advancing technical prowess combined with its

appreciation for the geography of long-range naval warfare pushed Japanese

engineers to construct the world’s longest-range, hardest-hitting ships. Japan

floated its first fully indigenous steel battleships in the mid-1890s and its

first aircraft carrier in 1922.

But No matter how a country industrializes,

there’s a list of non-negotiable inputs: labor for the factories, iron ore for

steel smelting, and coal and oil to power the process. Of that list, Japan had

only labor. Applying outside technology required that Japan venture out to

secure industrial inputs. Modernizing and industrializing in an era without

free trade demanded Japan become an empire. From the day Perry arrived, Japan

was condemned to transition

Japan’s first stop

was the island of Formosa, a largeish island just to the south of the Japanese

archipelago and home to contemporary Taiwan. Though it was nominally under

Chinese rule, the Japanese had little difficulty dispatching its defending

forces in 1895. Japanese imperial forces now controlled the northern half of

the First Island Chain as well as a military platform nearly within sight of

the Chinese coast. Unlike the occasional raiding and pirating by Japanese naval

forces during medieval times, now the Japanese could make their visits to the

Chinese mainland last. Next up: the Korean Peninsula in 1905. Korea’s rugged

internal geography mirrored Japan’s and produced an early Shogunate-like

political structure as well. Industrialized Japan faced few issues subjugating

the politically fractured, preindustrial Koreans. Attention turned to Manchuria

in 1931, a Chinese region replete with fertile farmland, coal, and minerals,

nearly everything Japan lacked. With these new resources and their preexisting

military presence in Formosa, the Japanese could easily project power up and

down the entire Chinese coast.

In World War II’s

early days, imperial armies surged from Manchuria to every part of the northern

Chinese core, reaching all the way to the Yangtze itself. Often launching from Taiwan, marine landings

secured control of Shanghai, Wenzhou, Fuzhou, Xiamen, the Pearl River Delta,

and Hainan Island. All the former European treaty ports in coastal China

concessions, except Macao and Hong Kong, were now Japanese imperial

territories. Less than two months after the fall of Paris to German forces, the

Japanese seized total control over French Indochina because,

There was but one fly

in the emperor’s ointment. The Americans occupied a choice piece of territory

smack in the middle of it all: the Philippines. From that position in the

middle of the First Island Chain, Americans could theoretically threaten

everything the Japanese had and wanted. It didn’t help that prewar American

policy was something Washington called Open Door. Officially, the policy was

designed to limit European predation of China, at that point a thriving

industry over a century old. Unofficially, the goal was to muscle the US of A

in on the action. Unofficially and very quietly, the intent was to box Japan

out of the region completely. Japan is best known in the American mind for the

attack on Pearl Harbor, but ultimately the Battle of Pearl Harbor occurred only

because the Japanese needed the Americans ejected from their Philippine

foothold in the East Asian Rim.

In under six months,

Japan had conquered nearly all European holdings in Southeast Asia, most

notably the territories that today comprise Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia,

Papua New Guinea, and Myanmar. Collectively these lands provided the Japanese

with everything they could need, from sugar to metals to oil. The empire may

have been a bit gangly, but if there was one thing the Japanese knew how to do,

it was how to manage an archipelago. Less than a century after Commodore Perry’s threatening of a “backward” nation,

Japanese forces in World War II stretched from the Aleutians to the edge of

India. Its navy vied with the Americans for control of the Pacific Ocean. It

all occurred against the cultural backdrop that allowed for events as horrific

as the Rape of Nanking, the impressment of Korean “comfort” women, and the

Bataan Death March. It was a pattern that did far more than give the Americans

pause. Assessing Japan’s rapid technological improvements, lightning military

advances, apparent lack of moral center, and the logistical restraints of

maritime warfare the Pacific Ocean away from home ports, the Americans chose

not to do battle with Japan’s armies at all. Rather than duke it out island by

island, the Americans seized only sufficient islands so that their naval and

air power could wreck the shipping routes upon which Imperial Japan depended.

Then, with the Japanese economy and military

complex on its knees, the Americans declined ground combat one last time,

opting instead for nuclear obliteration.

The Japanese knew

full well that military defeat meant the end of Japan as a country. There could

be no middle ground between a Greater Japan that was industrialized and the

fractured nonentity of the Shogunates.

But the Americans

surprised them, in large part because the Americans needed their defeated

Pacific foe. The Order’s core rationale was for

America’s new allies to stand between the Soviet Union and the United States,

and to do so willingly. The United States achieved this by imposing security

globally, crafting an international economic system, and granting unilateral

access to the American market. In one fell swoop, the Americans provided the

Japanese with everything Japan had fought for and ultimately lost, between 1870

and 1945. A position under the American nuclear umbrella was tossed in as a

cringe-inducing bonus.

Japan wasn’t so much

dismantled and rebuilt as upgraded. Japanese factories that had made weapons

were reconfigured to make sewing machines and household goods. Optical device

companies began making cameras instead of gunsights. Heavy industries switched

from tanks and planes to automobiles. Aside from a pair of newcomers, Honda and

Sony, the whos-who on the list of most powerful

Japanese firms, Hitachi, Toshiba, Mitsui, Mitsubishi, were the same names that

had dominated the Japanese system before the war.

The term “miracle”

to describe Japan’s postwar boom is a misnomer. It was as highly planned,

tightly regulated, and deliberate as every step of Japan’s evolution since

1852, and the hoped-for outcome was the fruition of Japan’s considerable

domestic ambitions backed by the full force of the American economic,

political, and military system. In a single generation, Japan recovered from

the destruction and despair of its World War II defeat to become the

second-largest economy in the world.

That achievement was

notable from any angle: the unexpected preservation of the Japanese way of

life, the ongoing success of the Japanese technocratic experience, the

anchoring of Japan in the American

alliance structure, and the prevention of a large-scale Soviet expansion in the

Pacific theater. But in becoming so big so fast, Japan may well have been the

first country to make the Americans second-guess the Order’s very existence.

One of the Japanese

leaders’ favorite Order-era tools to maximize their economic strength was

currency manipulation. The central bank would print lots of yen and use them to

buy dollars on international markets, driving the yen down in value versus the

dollar, making Japanese goods relatively cheaper, and thus encouraging

Americans to purchase them.

Contemporary Japan

Contemporary Japan

faces a thorny series of difficulties, most of which are disturbingly similar

to Japan’s late-nineteenth-century concerns. Luckily (for Japan), just as the

Japanese were able to massage several of their preindustrial problems into strengths,

the same logic holds true for the Japan of today. The first issue is the

looming iceberg of Japan’s demographic implosion. The niggardly amount of

flatland in Japan that has so shaped the country’s political, agricultural,

industrial, and technological history has similarly shaped Japan’s demographic

structure.

Once one filters out

countries that aren’t really countries (think Monaco) and takes into account

the fact that over 80 percent of Japan’s land is uninhabitable, Japan is the

world’s most densely populated and fifth-most-urbanized country. Cramming everyone

into tiny urban condos generates some amazing economies of scale and

wonderfully efficient city services, but it makes it damnably difficult to

raise children.

Japan’s ruggedness

prevents the formation of something commonplace in America: suburbs. If you

want kids, you cannot move outside the city and commute in; you must squeeze

them into your postage-stamp-size apartment. (The average Tokyo apartment comes

out to less than 275 square feet per occupant.) In such circumstances, there

are a lot of only children, a fair number of childless couples, and a far from

an insignificant number of folks who never marry because they don’t want to

share their space.

The demographic

degradation has been going on since the majority of Japanese relocated to the

cities just before World War II, and passed the point of no return shortly

after the turn of the millennium. Japan can now look forward to an ever-rising

bill for pensions and health care, an ever-shrinking tax base, and a deepening

shortage of workers in every field.

There are a few

bright spots. Japan has the indubitable advantage of having gotten (very) rich

before becoming old. As the country with the highest proportion of retirees in

its population, Japan has the incentive for finding better and more

cost-effective methods of caring for the elderly, but it also has the financial

muscle and high-tech economy to do so. Japan isn’t simply land with higher

sales of diapers for adults than diapers for infants; it is a land where

elder-care facilities are partially automated.

Japan is approaching

the worker shortage of the twenty-first century in the same way it approached

its higher cost structures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth—by being

more advanced. Japan is the most technologically advanced, and Japan literally

has a

national robot strategy. In fact, I recently

mentioned the new robotic form of Buddhism...

None of which is meant

to take away from the seriousness of the threat. Japan isn’t just a rapidly aging nation as is the case with China. It

is already the world’s most aged nation, leading humanity’s charge into

demographic oblivion.

Strength from weakness, again

In these interlocking

problems, there lies s interlocking solutions the Japanese are already

implementing. First up, the Japanese are fairly nondenominational when it comes

to where they get their electricity. They have to be. The enclaved nature of

Japan’s cities means there cannot be a meaningful national grid, only the

Greater Tokyo region has any meaningful large-scale interconnections. Each

urban center must maintain its own electricity system, and so each city has

found itself forced to overbuild generation capacity and diversify it among

several different fuel inputs so that, should one system fail due to lack of

imported inputs, the others can take up the slack. Nuclear, coal, oil, natural

gas. Each major city independently has them all.

The 2011 Tohoku

earthquake and the subsequent Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant meltdown

put the system’s pros and cons on global display. The cons were obvious, as the

Fukushima region, as one of the least densely populated parts of Japan, also

had the least-redundant power system and so suffered blackouts and brownouts

for months. However, it was the only region to do so. The self-sufficient

nature of each city’s power systems prevented cascading failures; Tokyo largely

recovered within a month. Since then the Japanese have steadily expanded

interconnections to prevent something like the Fukushima brownouts from

occurring again. Because every region has such vast amounts of surplus

generation capacity, the only way to generate even a regional blackout in the

future would be a major war that puts foreign boots in Japan or shuts down all

trade lanes for several weeks. The disruption would have to interrupt oil and

natural gas and coal and uranium shipments. Taking out one or two wouldn’t do

much. Preserving this overlapping energy security is so important to the

Japanese that they’ve been bringing their entire nuclear system back online

even as other countries were so spooked by the Fukushima disaster that they’re

going nuclear-free. Next up is the labor and materials problem. Demographic

aging means Japanese labor is expensive (and getting more so). Japanese

industrial inputs are huge and varied (and getting more so). Japan’s position

at the far edge of Asia gives it some of the longest, most vulnerable supply

lines in the world. Importing ever-larger volumes of ever-more diverse

materials from ever-longer distances for processing and manufacturing by an

ever-shrinking and -aging workforce is a recipe for failure. So Japan is

changing its industrial model. Most are familiar with terms like outsourcing

(shifting production overseas but shipping the product back to the home market)

or resourcing (returning production home). Japan has become the master of

resourcing: shifting production to another country to serve that specific

market (aka “build where you sell”). Doing so does far more than place Japanese

products on the right side of currency, military, political, and tariff

barriers.

It pre-positions the

Japanese industry within the handful of countries with stable-to-growing

demographics (and thus stable-to-growing markets). It gives the host country a

vested interest in protecting industrial and energy input supply chains that

indirectly benefit Japan. It generates scads of hard currency that can come

back home to mitigate the loss of income tax from a shrinking worker base. And

in the long run, it buys the goodwill of the host country, which Tokyo hopes to

cash in on other issues. The resourcing trend has already become so deeply

enmeshed in the Japanese industrial system that Japan itself no longer produces

a large percentage of its products for export. In the auto industry, for

instance, only a fifth of Japan’s internal manufacturing is meant for markets

outside of Japan. Japan is now one of the world’s least trade-dependent

countries. It keeps much of the high-brainpower work, especially design, at

home. If a supply-chain system needs to be broken up, the higher-end and

final-assembly work often go to the United States, Texas, Kentucky, Alabama,

and South Carolina being favorite spots. It has been a long time since 1980

when Japan was a global export leader. Resourcing doesn’t solve everything.

Even with mounting technological advances that squeeze lower-skilled labor into

a smaller and smaller piece of the process,

The next part of the

solution is firming up relationships with countries that co-locate both industrial

inputs and those initial processing steps that are low-skilled-labor intensive.

For the most part, the countries that check those boxes in the industries and

markets Japan cares about are in two regions. The first is the Western

Hemisphere, where a combination of American action and sheer distance is likely

to keep the chaos of the Eastern Hemisphere at bay. Because there are no

competitors, no powers whatsoever, between Japan and the Americas, Japan should

be able to retain access. The second is Southeast Asia. Except for Thailand and

Singapore, all are resource-rich and boast young, growing populations. For

their part, Thailand and Singapore are far more technologically advanced and

are already heavily integrated into Japanese manufacturing systems. That

Southeast Asia and the Western Hemisphere have the two greatest concentrations

of the foodstuffs the Japanese prefer is a bonus. Raw materials and processing

in South America and Southeast Asia. End markets in Southeast Asia and

throughout the Western Hemisphere, with an emphasis on the United States. It’s

a neat fix with only one itty-bitty problem.

Dealing with China

Today, of course, China

has the problems related to the Coronavirus which also already erodes

its influence in Southeast Asia, but even without that few in the Chinese

bureaucracy have any experience, or even memory, of dealing with a real

economic slowdown, much less an existential crisis as is happening now. The

Chinese have known nothing but increasing stability and wealth since the

post-Mao consolidation of the late 1970s. A late-stage, lifelong bureaucrat in

2020 would have been no older than twenty-six the last time the Chinese knew

civic breakdown, political chaos, and famine. There’s no institutional memory

of or skill in dealing with the political and cultural fallout that recessions

bring, much less something more typical of Chinese history. Balls will be

dropped. Minds will be lost. Chinese history provides literally dozens of ways

China can fall apart, most involving the Chinese system seizing up from top to

bottom and then breaking into factions:

Along economic lines:

the north, center, south, and interior don’t cohere well unless forced./ Along

class lines: the urban rich of the coast have far more in common with outside

powers than one another, much less with the seething interior populations./

Within the Communist elite: the culture of bottomless financial resources has

generated a mass of corruption that if

vomited forth would either break China into mutually antagonist pieces or

devolve it into a kleptocracy, and it isn’t clear which would be worse for the

citizenry.

In these scenarios,

China doesn’t so much stew in its own juices as boil in its own blood, and that

is before the Communist Party has to make any decisions about how violent it

might be in its efforts to preserve a unified China. The last thing on the Chinese

mind will be venturing out into the wider, more dangerous world.

On the off-chance,

Beijing can keep it together in an environment of epic disruption and civil

breakdown, the idea that the central government might consider a Blammo! approach to East Asia cannot be entirely

discounted. Let us be clear. Such an effort will absolutely fail. China is

utterly incapable of shooting its way to resource security or export markets or

a diversified domestic economy. Just as important, the country on the receiving

end would not be the United States. The Americans are out of reach, and even a

mild American counteraction against Chinese interests would utterly wreck

everything that makes contemporary China functional.

Instead, a failing,

belligerent China would be Japan’s to deal with. Gun-for-gun and ship-for-ship

the Chinese should be able to overwhelm Japan, but a sane Chinese leader can

read a map and knows full well that any conflict with Japan is not about equivalency;

it’s about range and position, both of which Japan has but China lacks.

In an environment in

which global energy shipments become compromised because of destabilization

elsewhere in Eurasia, there would not be enough industrial inputs, first and

foremost oil, available for everyone. Southeast

Asia consumes about as much as it produces, so it is out of the game.

The Europeans retain a relevant mix of both naval reach and political links to

their former colonies in Africa to secure those supplies, supplies that will no

longer be available for China. That leaves the Persian Gulf, five thousand

miles distant from Shanghai, as the only significant remaining source.

Even China’s limited

expeditionary capacity is not as good as it sounds. Nameplate operational

vessels very roughly suited to the task that could even theoretically make the

trip in the first place. Along the entire route, they will be operating in or

near potentially hostile powers, such as Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia,

Indonesia, and India, and doing so without a smidgeon of air support. Defending

a string of, at a bare minimum, eighty-four slow, fat, supertankers sailing

through moderately to extremely dangerous waters at any given time is simply

impossible with the navy China has.

Japan, in contrast,

has four aircraft carrier battle groups that can make it that far. The point is

less than the Japanese would use carriers for convoy duty, and more than the

Japanese could scrub Chinese naval power out of existence from Hormuz to Malacca

with a minimum of fuss. In a shooting war, the only tankers that reach East

Asia are the ones the Japanese let through. Even worse (for the Chinese),

the Japanese only have one-third of

China’s oil import requirements, and Japan will have the option of sourcing

fuels from the Western Hemisphere to boot. China would find itself outreached

and outmaneuvered and out of options, and ultimately out of fuel. And because

the Chinese cannot compete with the Japanese in the Persian Gulf or the Indian

Ocean, the only option left would be to strike at Japan directly.

In any real shooting

war, the Chinese can do a lot of damage. China’s air force and missiles could

probably sink everything floating within several hundred miles of its shores,

which takes out pretty much everything within the northern three-quarters of the

First Island Chain. Longer-range missiles could rain down on Japan to great

effect: Japan is heavily urbanized, and Japan’s cities often do quadruple duty

as population centers, seaports, naval bases,

and air force bases. Even with American assistance, most would suffer

significant damage. Without American anti-ballistic-missile defense, it would

be much worse. Civilian casualties would easily reach the hundreds of

thousands.

For a mentally

untethered Chinese bureaucrat with no sense of history or context or

consequences and facing massive stress throughout the entire Chinese system,

the war might seem the perfect release of cathartic nationalism. But that’s all

it would be China lacks the naval wherewithal to follow up such an assault with

a First Island Chain breakthrough, much less an amphibious assault on the Home

Islands. Aside from killing (a lot of) Japanese citizens, it would achieve

nothing, well, nothing that would work out well for China.

First, China is a

trading country that imports nearly all its energy and most of its raw

materials. Sinking the ships near China’s shores means no ships will sail near

China’s shores for a good long while. The Chinese will have then caused their

own economic collapse, social breakdown, and famine.

Second, Japan is no

nobody. Japan may have surrendered unconditionally at the end of World War II,

but that doesn’t mean it disarmed. The Americans needed the Japanese equipped

and standing upright to help face down the Soviets. Consequently, military production

in Japan never went away, and it is doing more than making machine guns. The

stealth F-35 jet will form the backbone of American airpower for the next two

generations? Mitsubishi Heavy Industries runs licensed

production of it in Japan.

Japan doesn’t only

build but also designs its own naval vessels and has since the 1880s. Japan’s navy

is easily the second-most powerful expeditionary force in the world. China’s

first designs date and the Kaga, will soon be carrying the aforementioned F-35s

and so will pack more punch than nearly any ship in history save the American

supercarriers. These mobile airbases enable the Japanese to engage in offense

or defense wherever they want and, for the most part, out of range of Chinese

anti-ship defenses.

Japan’s air force has

sufficient reach to strike the Chinese mainland in any war scenario, and would

eagerly prioritize any targets that might grant the Chinese future military

options. At this point, the Chinese will have lost their entire navy, the dry

docks that would enable them to float more ships in the future, and the energy

pipelines from Russia, which provide China with the bulk of its imported energy

that doesn’t come in via ship. Those fat container ports that crowd the Chinese

coast would certainly be reduced to TV- and shoe-strewn craters.

Third, China’s

situation vis-à-vis Japan is more than a bit like Japan’s position vis-à-vis

the United States at the dawn of World War II. The Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor in 1941 failed to sink the most powerful units of the American navy, its

carriers, which were out to sea. Japan’s navy is fully blue-water and doesn’t

spend a lot of time in port, a habit likely to intensify if geopolitical

tensions are running high. Hitting Japan not only wouldn’t remove Japan’s navy

from the board, but it would also give the Japanese full justification to treat

all Chinese merchant shipping anywhere in the Pacific and Indian Oceans as

prey. In less than a month, China’s entire global position would dissolve into

dust. That time frame assumes that the Chinese do not fall prey to a Japanese

first strike and that the Indians, Koreans, Vietnamese, Americans, and others

remain neutral.

One way or another,

this will all end excruciatingly badly for China, and even if the Chinese land

a series of sucker punches on the Home Islands by launching the largest

assaults on civilian targets since World War II, it is Japan, not China, that

will be the last man standing.

Asia after China

The countries most

concerned about Chinese power are the countries best positioned to do something

about it, and to do so by allying with the Japanese.

Luckily for Tokyo, Japanese

relations with India are as good as China’s relations with India are bad,

and that difference alone might prove enough to cause China’s defeat in a war

with Japan.

Next up are the

littoral states of Southeast Asia. China has done pretty much everything

possible to aggravate all of them. Economically, the Chinese have attempted to lock them all into dependency relationships via the One

Belt, One Road system (especially the Philippines and Malaysia).

Politically, the Chinese don’t hesitate to inflame internal tensions,

especially when there’s a bit of historical umbrage in play (especially in

Vietnam), or a Chinese population that can be riled up (especially in Malaysia

and Indonesia). Strategically, the Chinese have

attempted to seize the entirety of the South China Sea, expanding atolls

and emplacing significant military assets throughout the area (which bothers

pretty much everyone).

At a glance, it is

easy to see why Beijing feels it can get away with being bossy. The Southeast

Asian navies are piecemeal at best. But this isn’t about confrontation. It’s

about access.

Indonesia and

Malaysia are well beyond the reach of the bulk of China’s navy, but together

they control the all-important Strait of Malacca, the gateway to Persian Gulf

oil and the European consumer market. Closer in, Vietnam and the Philippines

flank the west and east sides of the South China Sea, the first leg of the long

journey from the Chinese mainland to those same destinations. China must have

at least passive acquiescence from all of them to maintain its import and

export shipping. All it would take to transform the South China Sea and Malacca

into no-go zones for Chinese shipping would be a few dollops of military

assistance from an eager Japan.

Taiwan is an even

more obvious recruit. For China, the “wayward province” propaganda line is from

the heart. Moving against Taiwan just might provide the Chinese people with a

patriotic victory. All those shiny new ships the Chinese have that cannot penetrate

the First Island Chain or attain global reach are more than enough to

broach Taiwanese defenses. The more

economic, cultural, financial, diplomatic, and military pressure China finds

itself under, the more economic, cultural, financial, diplomatic, and military

pressure China will put on Taiwan.

But the Japanese can

read maps as well; Taiwan’s physical position is critical. It serves as an unsinkable

aircraft carrier that could end Chinese internal coastal shipping between

northern and southern China, and as

Taiwan is littered with anti-air defenses, nothing less than a full

amphibious assault can take it out of the equation. Even worse (for the

Chinese), it really wouldn’t matter how an assault on Taiwan would end, because

even an outright Chinese occupation of Taiwan doesn’t solve China’s problem of

being far from its resource needs and end markets. It all still ends with

Japanese regional primacy: a war-wracked Taiwan would be formally folded into

Japan’s military sphere of influence, while an intact Taiwan would be formally

folded into Japan’s economic sphere of influence.

The shifts in

circumstance will be most extreme for the two Koreas. Both Seoul and Pyongyang

spent the past seven decades attempting to play Washington, Moscow, Beijing,

and Tokyo (and each other) off one another in attempts to carve out a bit of

geopolitical space. With Russia’s decline (more on that in later chapters), the

United States’ disengagement, and China’s choice of collapse or retreat, most

options have vanished.

The smart play would

be to seek de facto economic fusion with reemergent Japan. Japan will control

the regional security alignments that are absolutely required if the South

Koreans want to continue with their import-driven/export-led economic system,

and the Japanese–Southeast Asian axis will prove just as central to ongoing

Korean economic development as it will for Japan’s own. In a China-less Asia,

North Korea will have lost its primary sponsor and source of both raw materials

and consumer goods. Economically, it is a clean, easy decision.

Politically, it is

anything but. Korean history on both sides of the DMZ is replete with examples

of defeat and humiliation at Japan’s hands. The most pressing Asian issue of

2030 onward will be how the two Koreas relate, or fail to relate, with Tokyo. It

is far from a minor issue. North Korea

is already a nuclear power, South Korea could become one nearly as quickly as

Japan, and both Koreas are armed to the teeth.

There might be room

for some version of China in a Japanese Asia, regardless of whether the Chinese

opt for a war of national destruction or a less-explosive national

disintegration. The question controls. Japan will undoubtedly be willing to

fold bits of China into its new system of resource supply and market access,

but only if those bits accede to Japanese security primacy. Southern coastal

portions of China will find that just peachy. Areas farther north will prefer

the word “traitorous.” The age-old internal Chinese wheel of imperial center

versus rebellious periphery will spin once more. Most likely a host of southern

Chinese coastal cities will again be folded into economic networks that have

nothing to do with their countrymen.

No matter who emerges

most intact from the region’s inevitable convulsions, most players in most

sectors will lose their biggest markets, their biggest suppliers, or both.

Adjusting to the new reality will generate literally thousands of follow-on

complications and competitions, which will reverberate for decades.

Few countries on

Earth have as positive a relationship with all sides of the Persian Gulf as

Japan does. Japan’s status as one of the very few countries of the world that

can bring naval power to bear in the Persian Gulf will induce the region’s

quarreling countries to take any requests from Tokyo very seriously. It is less

gunboat diplomacy and more a client who leads a coalition who pays in cash and

guards their own deliveries.

But the Persian Gulf

is still the Persian Gulf. Regardless of how China’s fall and Japan’s rise

manifests, the Japanese still must ensure the sanctity of supply, both for

themselves as well as for anyone they wish to be in their orbit. For the states

of the Persian Gulf, their end markets will be wholly at the discretion of the

only naval power that can reach the Gulf, ensure product delivery, and care

enough to do so regularly. That will no longer be the United States. It will be

Japan. One way or another, the politics of the Persian Gulf are about to be a

Japanese problem.

Conflict’s end in

Asia heralds the dawn of a fundamentally new age of Japanese primacy, not just

in Northeast Asia, but in Southeast Asia as well, with tendrils of economic and

military influence reaching to the Persian Gulf. At some point, the Americans

will behold what Japan hath wrought and have some very serious second thoughts.

Considering the time it will take the Japanese to consolidate their gains in

the face of their demographic decline and the time it will take the Americans

to shake themselves out of their internal political narcissism.

For updates click homepage here