As we will see in the

example of Pakistan, India and Indonesia Anthropologists Susan Gal and Judith Irvine

during the 1990’s already stated that Nationalist ideologies have the

capability to construct boundaries of languages from what had previously been

fluid interactions. 1

In the case of S.Asia/India, despite being the language of only a very

small percentage of elite educated in colonial institutions, English was the one language that could claim

some kind of pan-Indian cosmopolitan spread. But in the first decades of

India's independence, English, as the language of the colonizer, was perceived

as a foreign imposition, something which could never nourish the national

genius of Indians and which should be expelled as soon as possible. The riddle

then became what the indigenous language could serve as a national, official

language. While census data on Hindi speakers showed it to be the most widely

spoken language in India, it could never claim more than forty percent of the

population, and even this claim might well have been an artifact of the

practice of census-taking and language nominalization-for the process would

collapse speakers of many different speech-forms (dialects or languages) into

the category of Hindi. 2

In addition to Hindi,

twelve other modern languages with extensive literary traditions and millions

of speakers posed something of a hurdle to any presumptive declaration of Hindi

as a national language in the singular. What the constitution-makers chose as a

compromise formulation was a sort of three-tier management: legally,

"Hindi in the Devanagari script" was enshrined as the "official

language," with a safety-valve provisions for the use of English until

Hindi could be properly "developed" to assume all official and link

functions after a period of fifteen years. But this was a decision reached only

after significant debate, and only by the thinnest of margins according to the

testimony of the chairman of the constitution drafting committee, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar:

It may now not be a breach of a secret if I reveal to the public what happened

in the Congress Party meeting when the Draft Constitution of India was being

considered, on the issue of adopting Hindi as the national language. There was

no article that proved more controversial than Article 115 which deals with the

question. No article produced more opposition. No article, more heat. After a

prolonged discussion when the question was put, the vote was 78 against 78. The

tie could not be resolved. After a long time when the question was put to the

Party meeting the result was 77 against 78 for Hindi. Hindi won its place as a

national language by one vote.

By the time the first

fifteen years of constitutionally-permitted English use were about to expire,

an unexpectedly violent protest against Hindi took place. This resistance was

strongest in Madras state, wherein 1964 and 1965 several young men spectacularly

killed themselves (by self-immolation and drinking poison) in protest against

Hindi and in devotion to Tamil. Such objections were not limited to Tamil

speakers alone; Bengal and Mysore states and the then-autonomous Government of

Kashmir had serious reservations about Hindi assuming the sole status of

official language.3

The argument against

Hindi as the sole official language, should English be de-certified as an

acceptable alternative, was that although the Hindi speakers presented the

question as simply a matter of national expediency, in all cases where Hindi

was closely in competition with another language (Urdu and Punjabi, notably),

the Hindi lobby displayed its rampant chauvinism and attempted to impose itself

as if by right. The Hindi language advocates such as the Arya Samaj, Arya

Sanskriti, Arya Bhasha and Arya Upi alienated Muslims

and Sikhs in the North, their co-religionists in the south-by virtue of the

south's own growing Dravidian pride-could hardly be willing supporters either.

So the official

language compromise with English perdured, conceptualized as perennially

supposed-to-be-superseded-by the more "Indian" Hindi, though the

hindsight of more than fifty years suggests that will never come to pass, not

to mention the fact that Indian literature in English and the dramatic rise in

global prominence of Indian science (conducted and published virtually entirely

in English) has very effectively established the language's national bona

fides. At the same time, early planners' concern that Hindi was not yet

suitably "developed" for modem life has surely been answered; the

language has undergone something of a wholesale transformation since

Independence, having been endowed with a highly

Sanskritic vocabulary for the lexicon of modern life. Rather, this

compromise formulation of the official language is "Hindi in the

Devanagari script" supported by English has, over time, proved to be a

solution that appears to least offend-though notably not the unitary national

language that had originally been imagined.

Aside from the matter

of official language was the dilemma of "linguistic provinces." This

was a question of political administration debated long before independence;

the solution would, in fact, replicate the decision the Indian National Congress

had taken to facilitate its anti-colonial struggle. Under Gandhi's leadership,

the Congress had long championed Hindi-Hindustani as the emblematic all-India

language, in both Devanagari and Persian script forms. But the Congress as well

recognized that in terms of organization and political expediency, it could

better function through a regional-language architecture. After Independence,

the Constituent Assembly appointed the Linguistic Provinces Committee to study

the issue. No easy compromise could be found; to be sure, the committee

recognized that there was considerable demand for the redrawing of provincial

boundaries and that administering education, public life, and legislatures

would be expedited if they could be organized into more homogenous linguistic

units. But they were concerned above all about whether the formation of new

boundaries along linguistic lines would bring new sub nationalisms into

existence, and further what the impact might be in terms of creating new

relations of majority-minority dynamics.4

For example, should a

new Kannada-speaking state be carved out of Madras and Mysore states, a

significant minority of Marathi-speakers would find themselves in a new

subordinate position? Within the south, in what was then-Madras state,

agitations emerged for a separate state of Telugu speakers as well as a

partitioning of Marathi and Kannada speakers. Gujarati speakers in Bombay State

argued for a separate Gujarati-speaking state; Marathi-speakers wanted a

Maharashtra. Punjabi-speakers sought to rescue themselves from minority status

in a Punjab that had suddenly become primarily Hindi speaking as a result of

Partition and the exodus of millions of Punjabi-speaking Muslims to Pakistan.

The question of linguistic provinces became a serious matter of public debate,

with the biggest names in Indian political life issuing reports either

recommending a linguistic province's reorganization (Ambedkar, for example) or

against, it, for example, Patel, Sitaramayya, and Nehru. 5

The argument against

however raised the specter of imminent Balkanization, invoking the recent

trauma of Partition and the necessity for the Indian Union to foster great

unity rather than further divisions, exemplified by this sentence from the

Patel, Sitaramayya, and Nehru report: "The context demands, above

everything, the consolidation of India and her freedom...the promotion of unity

in India It demands further stem discouragement of communalism, provincialism,

and all other separatist and disruptive tendencies.6

Despite this, a

massive reorganization of state boundaries did indeed take place, in shifts,

absolutely along linguistic lines, and through a process of combining princely

states and carving up the huge British-organized "presidencies."

First, the 1953 Andhra State Act carved a Telugu-speaking state of Andhra out

of Madras. Chandemagore was folded into West Bengal

in 1954. Then the 1956 states reorganization produced the "new"

states of Andhra Pradesh (by adding more territory to Andhra), Kerala, Madhya

Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu; it also redesigned the borders of Himachal Pradesh,

West Bengal, Assam, Bihar, and the various Union territories. The 1959

Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh Transfer of Territories Act reapportioned land to

each; the 1960 Bombay Reorganization Act created Gujarat and Maharashtra; the

1962 Nagaland Act created Nagaland; the 1966 Punjab Reorganization Act forged a

new Hindi-speaking Haryana and created majority Punjabi-speaking Punjab. The

1968 Andhra Pradesh and Mysore Transfer of Territory act created

Kannada-speaking Karnataka, and finally, the 1971 North-eastern States

Reorganization Act threw up Meghalaya, Mizoram, Tripura, Manipur, and Arunachal

Pradesh. The 1990 language conflict in Bangalore for example, has involved

anti-Tamil demonstrations, and protests against attempts in 1994 to broadcast

Urdu-language news on local (state-operated) television Bangalore, resulting in

protests.7

Nearly fifty years

after the reorganization of the major state of 1956, most contemporary

observers judge the administrative organization to have been a policy success,

for language conflict is now relatively rare (again, Assam the salient

exception) and language riots practically non-existent.so Did the creation of

more homogenous administrative territories produce new sub nationalisms? From

the perspective of the center, the answer appears to be broadly no. Yet if we

ask this same question from another vantage point, that of speakers of a

minority language within the linguistically demarcated states, we do find that

the majoritarian language hegemony Patel, Sitaramaya,

and Nehru worried about has come to pass. Two points should be noted in this

regard. First, for minority language speakers within states-using Dua's example

of Dakkani speakers in Mysore-the required language

repertoire can be as high as five languages (Dakkani,

high Urdu, Kannada, Hindi, English). This is a dramatic load compared to a

Hindi belter's ability to get by studying only Hindi and English.8

Yet this appears not

to be a significant source of conflict, and in any event, high levels of

multilingualism have long characterized the South Asian region. But the second

point, perhaps more apposite, lies in the way that new relationships of

linguistic categories have indeed created new minorities and new majorities

with unequal relations of power. After the reorganization of the major state in

1956, individual states in India passed their own state-level laws to promote

and develop various official languages of the state. The composite Hindustani

effort would end, to be replaced by separate Hindi and Urdu broadcasts.

Regional nodes of AIR (renamed Akashvani, or ''voice

from the sky" in official Hindi), would create programming in regional

languages, following the pattern of the linguistic provinces. Doordarshan, India's state television, follows a similar

structure: national programs are created in Hindi and English, relayed

throughout the country, with additional programs created at the state level in

the various regional languages. India's unique literary heritage was considered

so critical for national development that a government resolution in 1954

created the Sahitya Akademi (India's National Academy

of Letters). It began operation in 1956. The Sahitya Akademi

exists entirely to serve as a sort of national bureau of literary recognition,

with programs to translate work from one Indian language into another, as well

as into English, not to mention the annual bestowing of awards for literary

merit in each of the languages recognized in the Constitution. This is a

self-conscious effort to establish a national sensibility of unity-in-diversity

through literature. Of course, the project is not without its conceptual

dilemmas. As Sheldon Pollock argues, a paradox inheres in the fact that this Akademi had to be created in order to forge awareness of

the national literature it assumes to already exist.9

Jyotirindra Das Gupta in turn

notes, the "Hindi literati" played a significant role in the

creation of modem standard Hindi-picking up from where the Hindi language

movement left off in the late 19th century, coining an extensive array of new terms for modern life from Sanskrit, and promoting

a brand new form of the language that aimed to create a veneer of a different

kind of linguistic genealogy, i.e., the modem inheritor of the great Sanskrit

tradition.10

The post Independence efforts to make a national language in

the singular fell on the sword of its own diversity, producing a multilingual

national policy that effectively mirrors the sort of multilingual existence

deep-rooted in the region. In this sense practices with much longer precedents

rode roughshod over the bureaucratic imagined idea of a national language. The

ideological "content" carried by the national language project and

its proponents, namely organizations seeking to fuse the national language and

thereby the nation with an Aryan overlay, was the most important feature of the

conflict with India's southern states, particularly Tamil Nadu. The Dravidian

anti-Brahmin populism which characterized the state's politics of the 50s and

60s could hardly have welcomed the introduction of a language explicitly

presented as some high-water mark of Aryan cultural achievement. This

demonstrates how the social-ideological context trumped the program for forging

national linguistic unanimity. Secondly, the case of India shows how and why

literature and its histories matter. Long senses of literary traditions

inscribe the history of regions with cultural exemplars, a narrative biography

of a language's past. These ideas are difficult to undo. But because of its

size, the decision to administer a federal system with states drawn along lines

of language communities, and considerable efforts to incorporate the work of

the many language associations as effective arms of language policy, perhaps

India cannot offer the most appropriate comparison for the language policy

decisions taken by Pakistan. The Pakistani nation-state sought to present Urdu

as the natural and exclusive emblem of the Muslim nation of the Indian

subcontinent, investing the idea of the language with a peculiar religious

sacredness, this claim would pragmatically dissociate the literary traditions

central to Pakistan's regional languages from the realm of faith. Partition

ushered in the era of the nation-form along with its essentialist presumptions

of large-scale uniformity, including in the realm of language. This pursuit, in

India as well as in Pakistan, drew upon teleological narratives of the past and

of a religious community that had their roots in a nineteenth-century language

controversy in northern India. Specifically, the presumption that Urdu was the

obvious national language of the region's Muslims was the outcome of two

intertwined phenomena: the geographical base of the Muslim League's primary

support, and the pre-history of what became known as the "Hindi-Urdu

controversy." Up until 1946 the primary support for the Muslim League's

Pakistan demand was located in the North-West Provinces, termed the

"Muslim minority" provinces. This was the very same territory of the contentious

Hindi-Urdu controversy that took place in the second half of the nineteenth

century. This meant that a salient political issue for Muslims in the region

was the "protection" of Urdu, even though Muslims in the vast expanse

of British India and the various princely states obviously spoke a wide variety

of other languages; but with the political core centered on the North-West

Provinces, ideas about who and what constituted Islamic India collapsed the

cultural imagination onto the great historical and cultural traditions of that

particular land to the exclusion of everywhere else. Indeed, the historical

record here underscores the contention of linguistic controversy, which paved

the way for a growing consensus that linked language and religion into the

slogans "Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan" in opposition to "Urdu-Muslim

Pakistan“." The social and literary histories of Hindi, Urdu, and their schismogenesis are now becoming voluminous.11

Given the factual

conundrum that neither Hindi nor Urdu, at least in the forms they would assume

by the twentieth century, had any particular role in sacred religious texts,

their opposition appears all the more perplexing in retrospect. In effect,

these two languages would become the bearers of religion first, then nation by

proxy. In fact, what is called Urdu today could-at any point from perhaps the

late sixteenth through nineteenth centuries-have been called, variously, Hindu,

Hindi, Dihlavī , Gujari, Dakhini or Dakkhani (دکنی), Rekhtah, "Moors" (a British coinage), Hindoostanic, Hindoostanee, and

so on...

The former usage of

"Moors" apparently was synonymous with "the black

language," at least for officers of the Royal army.12

The name

"Urdu" is itself a short form of "Zaban-e-Urdu-e-Mu'alla,"

or "Language of the Exalted (Military) Camp" -attesting to the belief

that the language's origins lie in the interaction of Turkish and

Persian-speaking military troops with indigenous Indian soldiers in the Mughal

employ. This is the standard narrative of Urdu's birth, though even that is

under revision.

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

argued that the name ''Urdu'' did not come into existence until the end of the

eighteenth century, the very tail end of the historical period which supposedly

produced the language. And that the belief that the name "Urdu"

referenced the military camp is incorrect, and that it refers to Shahjahanabad instead, and that the actual birth of Urdu as

a literary language stemmed from the production of works by Sufis in the Deccan

and in Gujarat.13

And like our above

case study suggested, As the nineteenth century continued, advocacy for Hindi

in the Nagari script continued to gain force, and the demands became political.

Hindi advocates petitioned the colonial authorities for the equal privilege to

use Nagari-script Hindi in the courts, and as well for the right to a

Hindi-language primary education. Pamphleteering for Hindi's right to

participate in the official spheres of public life allied the language with the

masses-the Hindu masses-and forged a discourse at once about religion and the

spread democracy, through language. Urdu was figured as a foreign imposition,

an alien script with alien words that came from alien invaders. As Hindi became

a more potent sociopolitical force, Urdu speakers felt themselves under attack.

Urdu then became a language in need of "defending," a language

represented by its partisan proponents as a core aspect of Muslim life itself.

The Hindi-Urdu Controversy in north India, in conjunction with movements for

religious reformation within Hinduism and Islam slightly predating and

continuing during the same period, participated in community schismogenesis, a process which at its endpoints, would

result in the complete association of Urdu with Islam and Hindi with Hinduism.

And while it is generally recognized to have been an important concern for

residents of the North-West Provinces, it rose to a similar level of primacy in

the territories which would eventually form Pakistan. In fact, by the time of

Pakistan's birth, the elision of Urdu-Muslim-Pakistan was complete, and yet

highly controversial. There was a disjuncture between the territorial

imagination of the Urdu Muslim synecdoche and the actual practical situation of

the territory that was Muslim-majority and which would become Pakistan.

In sharp contrast,

Indonesia's national language planners explicitly crafted Bahasa Indonesia as a

unique modem instrument of expression, one without a deep past, literally

"constructed" (Pembangunan) as one might build a gleaming skyscraper

to signal an ascendant national modernization. One was a religion, the other a

science.

Indonesia.

The similarities

between Pakistan and Indonesia are so striking that one wonders why the two

rarely received sustained attention in a comparative fashion. Born within two

years of each other-the two countries share a number of common features. Prior

to 1971, both countries were nearly the same size in population trends:

Pakistan had 75 million people in 1951, compared to Indonesia's 84 million in

the same year.14

Since 1971 and

Pakistan's truncation, Indonesia is much more populous, home to the largest

Muslim population in the world, and Pakistan is now the second; recent

population figures are 206 million for Indonesia (2000 census) and 150 million

for Pakistan (estimate based on 1998 census). Both countries are overwhelmingly

Muslim, approximately 97% for Pakistan and 88% for Indonesia.

Both have been ruled

by authoritarian regimes for the better part of their independent existence,

and have long had highly centralized polities. The military has and continues

to play a disproportionate role in politics, industry, and society in both countries.

Up until the mid-1970s, both countries had similar human development indicators

in terms of literacy and per capita income. Indonesia's economic miracle began

to take off with the discovery of oil in the early 1970s but really took flight

in the 1980s. Indeed it was not until 1986 that President Suharto would make

primary education universal in the country and by now a vast gulf of literacy

and education separates Indonesia from Pakistan. Both countries are home to

bewildering ethnolinguistic diversity, yet within that diverse mosaic, both

have a dominant ethnic group comprising approximately half of the population:

Punjab's 56% of Pakistan, and the Javanese 48% of Indonesia. For example,

illiteracy in Indonesia decreased from 39% (1971) to 10% (1999).

Both chose national

languages which were the first languages of only a tiny percentage of the

population: at independence, native Bahasa -Indonesia speakers comprised only

4.9% of Indonesia's population; native Urdu speakers comprised no more than

three percent of Pakistan (East and West wings; 7% of the West wing alone) at

the same moment. Most importantly for my argument here, Indonesia sought to use

Bahasa Indonesia to create a cohesive Indonesian identity, envisioned as

secular whereas Pakistan sought to use Urdu to forge a cohesive identity

envisioned as Islamic. Indonesia's efforts to propagate its national language

have by all accounts achieved successes that make Pakistan's troubled

experience with Urdu all the more striking, given the two countries' broad

similarities.

Bahasa Indonesia is

the state-developed form of a lingua franca, Malay, which had developed across

the sea trade routes in Southeast Asia. Malay is widely used in southeast Asia,

for in another national version (Bahasa Melayu) it is

the national language of Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, Singapore (where it is

one of the four national languages), and it is in use though without official

patronage in two southern provinces of Thailand. Malay is a member of the

Austronesian language family, as are many of the other major Indonesian

languages, such as Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, Batak. The region was deeply

influenced by contact with Hinduism and Buddhism, reflected in the fact that up

until the fifteenth century, Malay was written with a Sanskrit-derived script.

Malay developed in a context in which Tamil, Arabic, Javanese, Chinese,

Bengali, and Gujarati all interacted. Islam as we have seen elsewhere, came

relatively late to the region, via traders in the fourteenth century, but its

influence was quickly felt on the written language: between the fourteenth and

nineteenth centuries, an Arabic-derived script called "Jawi"

superseded the Sanskritic script.

With colonization by the

Dutch (Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia) as well as the British (British

Malaya, now Malaysia and Singapore), in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

a roman alphabet ("Romi") as well as the first dictionaries were

developed for this lingua franca, a preoccupation in particular of Dutch

philologist-colonizers. The roman script is now the official script in use

today for Malay Indonesian. As a lingua franca, Malay was used by traders and

those who encountered them in the region. Its minimalist grammatical features

(in its lingua franca form) bear witness to this: for example, verbs are not

conjugated for tense, there is no gender nor plural forms of nouns (plurals are

indicated by reduplication), word order is variable, and there are no honorific

forms. This sets Malay apart from Javanese, which has very

highly structured hierarchy embedded in the language itself.15

In Javanese, it is not

simply that one adds honorific titles or particles to words; rather, there are

distinct modes of speaking that depend on the speaker's place in relation to

the addressee. While Malay was a commercial language that spread-again, in a

lingua franca form-due to merchant travels, we should also note that Old Malay

was the language of the state of the Sriwijaya empire, centered in southern

Sumatra. The much more populous island of Java, however, was the site of the

region's literary giant, Javanese. It was an important language of the Majapahit kingdoms, and it includes extensive poetic

traditions, performing arts, and written epics. Javanese managed to survive and

indeed flourish from the impact of Sanskrit and Pali influence (early Hindu and

Buddhist periods) as well as the sacred language of Arabic when Islam gradually

became the dominant religion of the archipelago from the fourteenth century

onwards. The famed Javanese epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, are of course drawn

from the eponymous Indian Sanskrit literary works, the performance of which

comprises the primary form of popular theater in several distinct

puppet-theater forms in Java. Given the rich cultural heritage of Javanese, it

is perhaps surprising that this lingua franca, Malay, would become the national

language. But it was a purposeful choice, one made by those challenging

colonial authority. Nearly all narratives-oral or written-of Indonesia's

independence struggle and the development of Bahasa Indonesia as the national

language invoke the Sumpah Pemuda, or Youth Pledge,

as a moment that crystallized the fusion of the anti-colonial nationalist

movement with a vision of civic national belonging and a singular language.

Firstly: We the sons and daughters of Indonesia declare that we belong to one fatherland,

Indonesia Secondly: We the sons and daughters of Indonesia declare that we

belong to one nation, the Indonesian nation. Thirdly: We the sons and daughters

of Indonesia uphold as the language of unity the Indonesian language.16

This Youth Pledge,

taken by a group of nationalists at the second Youth Congress on October 28,

1928, forms the commemorative basis for the Indonesian nation and is celebrated

annually. This Congress-in the same way that Ekushe

functions for Bangladesh-marks the beginning of the historical narrative of the

Indonesian nation that culminates with its independence. Its significance is

widely accepted, and the story of the Second Youth Congress is told and re-told

today as the national point of origin. The Youth Congress chose a language for

this national exercise that they knew had only shallow, but far more

geographically widespread, roots in the region. It was the language of no one

for all intents and purposes-but the young nationalists felt (with great foresight)

that it offered the best opportunity to unify a disparate region into one with

a larger sense of cohesion. The Indonesian nation and its national language

were literally willed into being.17

Of course, two

moments in the pre-Independence history had lain some of the groundwork for

Indonesian to emerge with the possibility of becoming a national language.

First, the Dutch had patronized Malay and their work in developing dictionaries

and basic readers resulted in the systematization of bazaar Malay, or brabble Maleisch, into "school Malay," which then became

the language of educated Indonesian elite. See Hoffman, "A Foreign

Investment: Indies Malay to 1901." Professor Anton Moeliono,

the former head of Indonesia's Pusat Bahasa (Language Center) and the

intellectual inheritor of Alisjahbana's role in terms

of stewardship of the national language, believes that modern Indonesian grew

out of school Malay, not from bazaar Malay.18

It was, however, only

used by those fortunate enough to attend the limited number of colonial schools

(the number of Indonesians educated in Dutch was fewer still). Balai Pustaka,

the colonial publishing house, offered short literary works in this emergent

school Malay, while also publishing in Javanese and Sundanese. The nationalist

intellectuals, however, sought something different than a school-gibberish and

began to create new reading materials in Indonesian that would "satisfy

the demands for more nationalistic literature. Sutan Takdir

Alisjahbana was the towering figure among these

nationalists. His prolific writings-in English as well as in

Indonesian-exemplify the spirit of modernist enthusiasm for the great project

of new language-making as nation-making. High modernist ideals of systemization

led to spelling reforms, the development of new vocabularies for new fields,

and the emergence of literary magazines written in this new language. A mere

glance at the titles of some of his many English-language writings readily

illustrates his focus on the nexus of language, nation, and becoming modern. In

Indonesian, Alisjahbana would go on to found a new

literary magazine in 1933, Pujangga Baru ("New

Poet"), as well as take part in the writings which became known as the

"cultural polemics," or Polemik Kebudayaan. Secondly, the three years of the Japanese

occupation of Indonesia (1942-45), according to nearly every historian of

language in this period, eliminated what had been the prestige relationship of

Dutch to the archipelago by eliminating its use entirely.

One should

acknowledge however that in the case of all the independence movements

mentioned above (movements that imagined nations that had never before

existed), we're able to convert the masses who did not actually read. This

suggests that national consciousness can indeed coalesce through oral

communication, public addresses, and other forms of non-print communication

that can take place in multiple, even mixed, language forms.

To this one can add

that because language contact and geographical displacement imply various kinds

of social change, it is inferred that the contact between "Indus"

language and the Munda/Para-Munda languages was somewhat intense, implying a fairly

high degree of socioeconomic integration. The same was true later, of the

contact between OIA (presumably both the inner and outer varieties) and the

local languages, which presumably included both "Indus" and

Para-Munda. In both cases, if

"Indus" and Para-Munda were languages of the Indus Valley culture

(respectively a local language and an interregional lingua franca), then it

would not be surprising if such contact occurred; nor would it be surprising if

early speakers of Indo-Persian interacted with the local people in similar

ways, given the need of pastoralists for agricultural produce. Interactions

between Dravidian and Indo-Persian speakers appear to be somewhat later, and

perhaps occurred first in a place called "Sindh" also spelled Sind, which

is furthermore the name of a province of southeastern Pakistan. It is bordered

by the provinces of Balochistān on the west and

north, Punjab on the northeast.

In fact Dravidian

languages were present probably by 1000 BCE if not earlier. And Dravidian place

name suffixes are found in Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Sindh, and Dravidian may

have played a role in the southern cities of the

Indus Valley culture in Sindh and Gujarat. Outer Indo-Persian languages

probably appeared in this area by the mid-second millennium BCE or earlier.

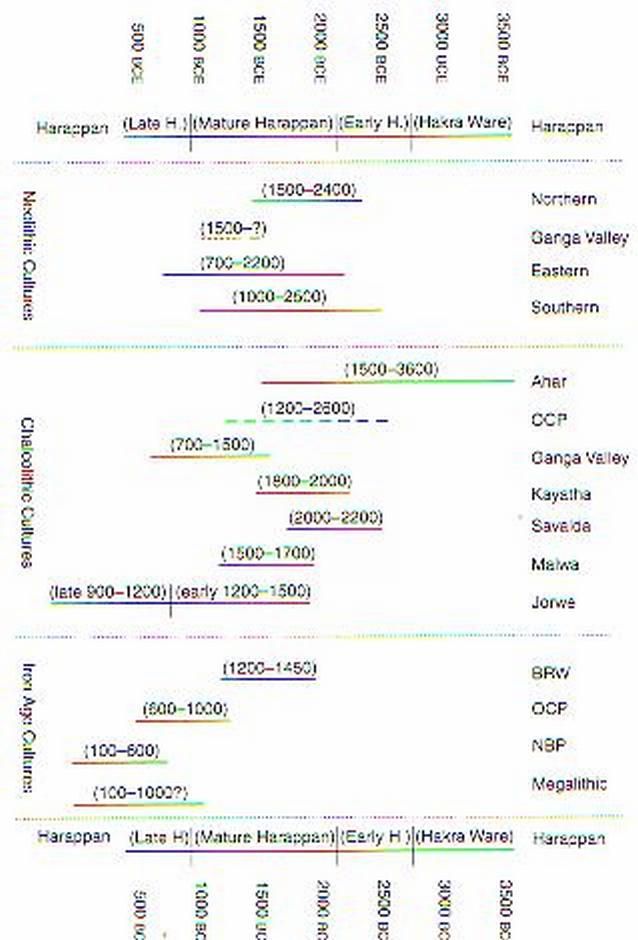

Following are early

languages in contact with each other in various parts of the subcontinent:

The Prakrits provide some suggestions of regional dialect

variation but there is no knowledge of the relationship between the literary

tradition that has been handed, and the actual usage of the majority of

Indo-Persian speakers. Evidence suggests that regional variation was probably

greater, even from the earliest times, than one can infer from any analysis of

the traditional texts. The Nuristani or Kafiri

languages, a separate branch of the Indo-Iranian languages, may have found

their way to their current locations a few centuries earlier. Korku, a North

Munda language listed above, is spoken in Nimar District of Madhya Pradesh. And

Speakers of outer Indo-European may also have

entered the Kosala/Avadh area from the Narmada across the Vindhya complex, via

the valleys of the Son and other rivers.

But for all its ups

and downs Persian is still spoken beyond the borders of Iran (as Dari, (درى). Dari is the variety of Persian spoken in Afghanistan,

where it is one of the two official languages, along with Pashto, and is used

as a lingua franca among the different language communities. Dari is also used

as the medium of instruction in Afghan schools, and beyond that in Tajikistan

(as Tajik), famed for its poetry.

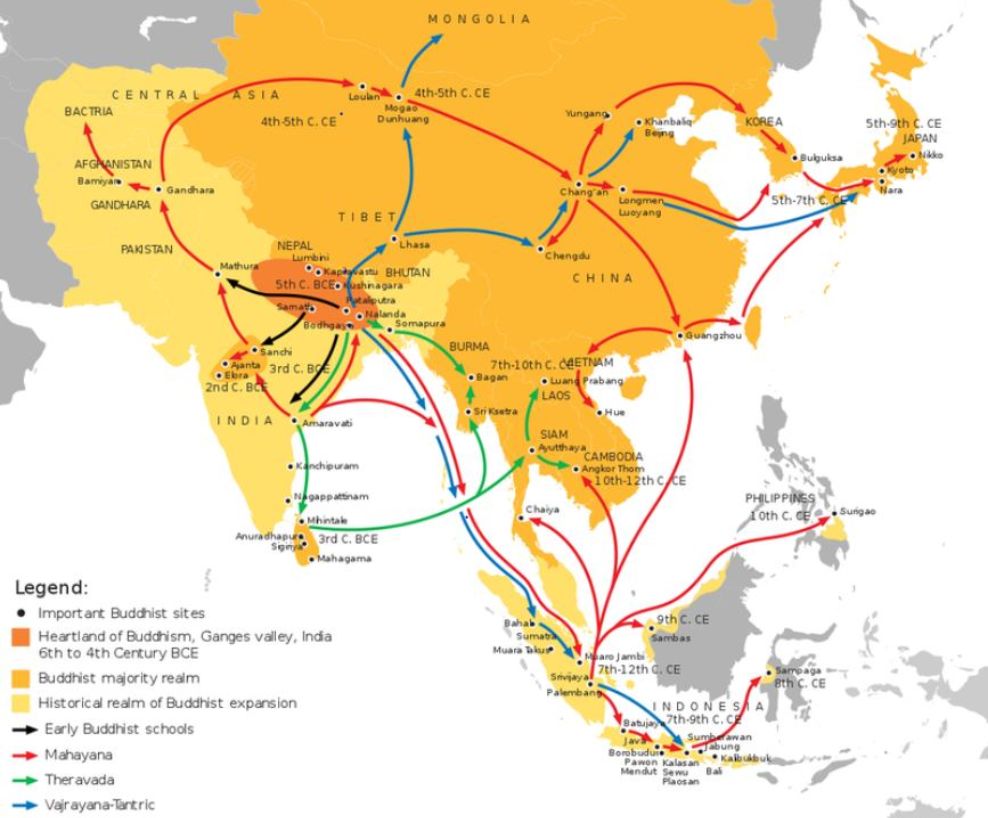

The attractions of

the Buddha's teachings caused the spread

of Sanskrit in its path northward, round

the Himalayas to Tibet, China, Korea and Japan (for all we know, Buddha

lived in the fifth century BC, in the lower valley of the Ganges,

speaking a Prakrit known as Magadhi). The faith he founded spread all over

India and Sri Lanka, as well as into Burma, its scriptures largely written in a

closely related Prakrit, Pali, but also, more and more over time, in classical

Sanskrit. Besides the spread to South-East Asia, the most influential path that

Buddhism took was to Kashmir, and back to the homeland of Sanskrit itself in

Panjab and Swat.

1. See "The

Boundaries of Languages and Disciplines: How Ideologies Construct

Difference." Social Research 62, no. 1, 1995. For an example of this

phenomenon in Africa see Patrick Harries, "Discovering Languages: the

historical origins of standard Tsonga in southern Africa," in Language and

Social History: studies in South African sociolinguistics., ed. Ranjend Mesthie (Cape Town: David

Philip, 1995.

2. See Arjun

Appadurai, "Number in the Colonial Imagination," in Orientalism and

the Postcolonial Predicament, ed. Carol A Breckenridge and Peter van der Veer,

University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.

3. For details see

Ramaswamy, Passions of the Tongue.

4. See Government of

India Constituent Assembly of India, "Report of the Linguistic Provinces

Commission," New Delhi, 1948, p.1.

5.Ambedkar, Thoughts

on linguistic States, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. B. Pattabhi

Sitaramayya. and Jawaharlal Nehru, Report of the Linguistic Provinces Committee

appointed by the Jaipur Congress, Dec. 1948; New Delhi: Indian National

Congress, 1953.

6. Patel,

Sitaramayya, and Nehru, Report of the Linguistic Provinces Committee, 4.

7. See Asghar All

Engineer, "Bangalore Violence: Linguistic or Communal?," Economic and

Political Weekly, October 29, 1994, Janaki Nair, "Kannada and Politics of

State Protection," Economic and Political Weekly, October 29, 1994.

8. For details see

Hans Raj Dua, Language Use, Attitudes and Identity Among linguistic Minorities,

ed. D.P. Pattanayak, vol. 8, CIIL Sociolinguistics

Series (Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages, CIIL, 1986.

9. Pollock.

"Literary Cultures in History,"

10. See

"Official Language: Policy and Implementation" and ''Language

Associations: Organizational Pattern" in Das Gupta. Language Conflict and

National Development, 159-224.

11 .On Hindi before

the nation, see especially Vasudha Dalmia, The Nationalization of Hindu

Traditions: Bharatendu Harischandra

and Nineteenth-century Banaras (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997),

Christopher R. King, One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in

Nineteenth-Century North India (Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1994), Stuart

McGregor, "The Progress of Hindi, Part 1: The Development of a

Transregional Idiom," in Literary Cultures in History, ed. Sheldon Pollock

(Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2003), Pandey,

The Construction of Communalism in Colonial North India, 201-32, Alok Rai,

"Making a Difference: Hindi, 1880-1930," Annual of Urdu Studies 10

(1995), Amrit Rai, A House Divided: The Origin and Development of Hindi/Hindavi

(Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1984). On Urdu before the nation, see Brass,

Language, Religion and Politics in North India, 119-81, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi,

Early Urdu Literary Culture and History (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001),

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, "A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture. Part 1:

Naming and Placing a Literary Culture," in Literary Cultures in History,

ed. Sheldon Pollock (Berkeley, London, New York: University of California

Press, 2003), Ayesha Jalal, Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in

South Asian Islam Since 1850 (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), 102-38.

Francis Robinson. Separatism among Indian Muslims: the politics of the United

Provinces'Muslims, 1860-1923. vol. 16, Cambridge South Asian Series (London:

Cambridge University Press, 1974), 33-132. On Hindi after the nation. see

especially Alok Rai, Hindi Nationalism (New Delhi: Orient Longman. 2000).

Harish Trivedi, "The Progress of Hindi, Part 2: Hindi and the

Nation," in Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia,

ed. Sheldon Pollock (Berkeley, Los Angeles. London: University of California

Press, 2(03). On Urdu after the nation, see Ahmad, "Some Reflections on

Urdu.", Aijaz Ahmed. "In the Mirror of Urdu: Recompositions

of Nation and Community, 1947-65;' in Lineages of the Present: Political Essays

(Delhi: Tulika Press. 1993 [1996]), Philip Oldenburg, "'A Place

Insufficiently Imagined': Language, Belief, and the Pakistan Crisis of

1971," Journal of Asian Studies 44. no. 4 (1985), Tariq Rahman, "The

Urdu-English Controversy in Pakistan," Modern Asian Studies 31, no. I

(1997).

12. See Henry Yule

and A.C. Burnell, Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words

and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographic, and

Discursive, Reprint ed. (London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1996 [1886]),

584.

13. Faruqi, Early

Urdu Literary Culture, and History, 60.62.

14. Central Statistical

Office Government of Pakistan, 25 Years of Pakistan in Statistics, Karachi:

Government of Pakistan, 1972, 4.

15. For details see

among other Joseph Errington, Structure and style in Javanese: a semiotic view

of linguistic etiquette, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988.

16. Quoted in The

Development and Use of A National Language, Yogyakarta, Oadjah

Marla University Press, 1980, 15.

17. See Benedict

Anderson, "Language, Fantasy, Revolution," in Making Indonesia:

Essays on Modern Indonesia, ed. Daniel S. Lev and Ruth McVey, Southeast Asia

Program, Cornell University, 1996.

18. Also see Moeliono, Language Development and Cultivation: Alternative

Approaches in Language Planning, 97-8 n.4.

For updates click homepage here