By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

The French Revolution And Napoleon

The Knights of Malta were

initially formed during the Crusades to aid Christian pilgrims visiting the

Holy Land. Named after St. John the Baptist, the ‘warrior monks’ took vows of

poverty, chastity, and obedience. Driven out of the Holy Land in the 1290s, the

Knights regrouped on Cyprus and then Rhodes before finally relocating to Malta,

where their headquarters dominated Malta’s famed port city of Valetta.

When the French Revolution broke out in

July 1789, it was immediately apparent that the Order of Malta would be one of

its victims. In August, the National Assembly abolished the tithes and feudal

rights that formed a significant part of the Order's income. In June 1791,

Louis XVI attempted (with the aid of a large loan made to him by the Order's

Receiver in Paris) to escape from France. When this resulted in his capture at

Varennes and return to Paris in the hands of a revolutionary mob, it was the

end of effective monarchism in France; and the sixty-six-year-old Grand Master

Rohan, on hearing the news, suffered a stroke that left him an invalid for the

rest of his life. In October 1792, the government of France, by now declared a

republic, confiscated the Order's entire property in the country. As the

revolutionary armies swept over Europe, the same confiscation was imposed in

the Austrian Netherlands, Germany west of the Rhine, and northern and central

Italy.

By late 1796 these seizures had deprived Malta of half

the income it drew from its European properties, and the knights in the lands

affected were left penniless. But suddenly, a savior appeared in an unexpected

quarter. On the death of Catherine the Great, the Russian throne was inherited

by Paul I, a ruler whose strange enthusiasms included a passionate admiration

for the Order of Malta. He summoned the dashing Giulio Litta to his side, who

had distinguished himself in the Russian Navy six years before and began

to show lavish tokens of his favor. The recently founded Grand Priory of Poland

had passed under Russian sovereignty with the Second Partition of Poland, and

Paul proceeded to pay off its significant arrears at a stroke and to increase

its responsions to 53,000 florins, thus making it a sizable contributor to the

Order's desperately reduced revenues.

Giulio Litta

Besides striking a worse material blow

at the Order than it had suffered even at the Reformation, the losses inflicted

by the French limited the candidates for the succession to the Grand Magistry, which was imminent. It would have been difficult

to elect a head from the parts of Europe where the Order's institutional

existence had been destroyed. Moreover, the new ruler needed to bring some

political protection against the ever-widening conquests of revolutionary

France. The Order could hardly elect a Grand Master from Spain, whose king had

allied with the nation that had murdered the head of his family. The patron

choices were narrowed down to Naples and the German Empire, and the protection

of Naples was more to be feared than welcomed. That is why by 1797, it was

considered certain that a German Grand Master would succeed Rohan.

This implied a very limited choice indeed. Owing

partly to the small size of the Langue, no German had ever been elected Grand

Master of the Order. From 1791, when Rohan suffered his stroke, an observer in

Malta would have seen a choice of just two German Grand Crosses resident on the

island:

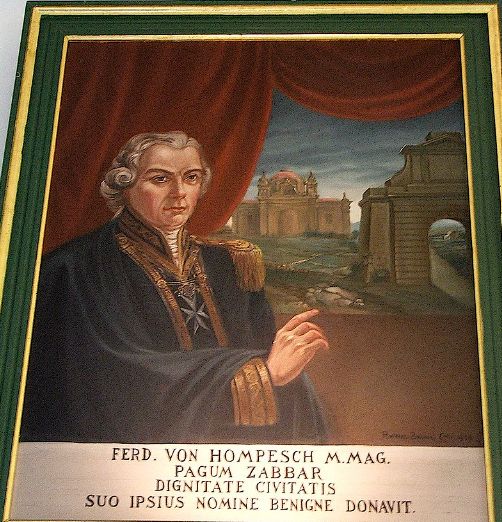

Franz von Schönau,

the Pilier of the Langue, and Ferdinand

von Hompesch, the imperial ambassador. Then,

seven months before Rohan's death, Schönau left

for his own country, and Hompesch succeeded

him as Pilier, becoming the only candidate

available. This was a fatal predicament. Hompesch was

simply a minor diplomat, weak in character, and a man whose career had shown a

consistent subservience to his sovereign to the detriment of the interests of

the Order. When Rohan died in July 1797, the Order thus found its choice

restricted to the worst superior it could have elected.

Von Hompesch

The conquests of the French revolutionaries made their

annexationist aims very obvious. Just before the election of Hompesch, France had conquered the Republic of Venice and

its possessions of the Ionian Islands, thus placing itself within striking

distance of Malta. Yet in the eleven months of his reign, Hompesch devoted himself to cultivating his popularity

at home without attempting to prepare his island against attack. Schönau, representative of the Order at the Congress

of Rastadt in 1798, warned him unequivocally

that the French intended to seize Malta and urged him to take precautions, but

the Grand Master preferred to pay no heed. This inactivity, coming after the

six years of enfeebled government during Rohan's illness, was fatal to the

morale of the island. The Directory had commissioned General Bonaparte to lead

an expedition to Egypt and seize Malta to give France a naval base in the

central Mediterranean. Nelson was cruising off Toulon to stop any such

departure, but Bonaparte gave him the slip, and on 6 June 1798, he appeared off

Malta with a fleet of between 500 and 600 vessels carrying an army of 29,000

men. When he demanded the right to enter the Grand Harbour to

take on water, the Order's Council applied the long-standing rule designed to

protect Malta's neutrality: only four ships should be admitted at a time.

Bonaparte rejected the condition and began his attack on 10 June.

The Fall of Malta

Two often-repeated mistakes about the

fall of Malta should be corrected. The first is that the knights could not

resist the French because their vocation forbade war against Christian nations.

That plea was only advanced by the French knight Bosredon-Ransijat,

who was openly a partisan of the republican regime, and he was promptly clapped

in prison for it. Apart from the consideration that the Republic's

anti-religious frenzy put it in a different category even from the Protestant

countries, whom the Order had always respected, the duty of neutrality towards

Christians had never been thought to exclude the right of self-defense.

The second mistake is that the defense

of Malta was undermined by the secret leaning of the French knights to their

own country. Again, this explanation is given color only by the defection

of Bosredon. In the previous months, an agent of

the Republic, Etienne Poussielgue, had been busy

in Malta, and he arrived at a very exact estimate of the number of French

knights who had any sympathy with the Revolution: fifteen, of whom only three

had what he called the energy to work actively for France. His estimate was

confirmed when Bonaparte, after conquering Malta, ordered all the knights out

of the island, including his compatriots, exempting only three on the grounds

of their assistance to the French cause. The remainder of the 200 French

knights who had taken refuge in Malta were identified by Poussielgue as irreconcilable royalists and as the

most resolute element in the defense. His judgment, which is obvious enough, is

confirmed by the details of the siege when nearly all the chief commands were

held by French knights, the only exception being the future Grand

Master Tommasi. The accusation against the French has obscured the real

complicity of the Spanish in the defeat of Malta. Their country was in alliance

with France, and their ambassadors ordered the Spanish knights to remain in

their Auberges and take no part in the fighting. Nevertheless, as there were

only twenty-five Spanish knights in Malta, this abstention had little influence

on the outcome.

The loss of Malta was one of the most

ignominious military surrenders in history and one of the most unnecessary. It

required no heroic feat of arms 1798 to defend Malta against the French; the

most cautious and defensive strategy would have done it. Against such an

overwhelming enemy, it was hopeless to resist a general landing; yet Valletta

itself was impregnable. The French would have faced a siege of many months, and

such a course was not open to them. Nelson alerted to Bonaparte's escape from

Toulon, was in hot pursuit and arrived off Syracuse on 22 June, only twelve

days after the attack on Malta began. The general had orders to abandon Malta

if its resistance threatened the Egyptian expedition. But a strategy of sitting

tight behind the walls of Valletta required a minimum of military sense and

steady nerves. Hompesch possessed neither, and

the fall of Malta became history.

Hompesch, seeking the protection of his Emperor, landed on 25

July at Trieste, where he set up the Order's Convent with the seventeen

professed brethren who remained faithful to him. But among the knights, the

news of his incredible betrayal was greeted with fury. One should bear in mind

that the statutes of the Order decreed the automatic loss of the habit for any

knight who surrendered a stronghold to the enemy.

The Russian coup d'état

On 26 August (Russian calendar) and 6

September (Westen calendar), the members of the Grand Priory of Russia

published a manifesto declaring that they regarded Hompesch as

deposed and invoking the protection of Czar Paul I proclaimed that he

took the Order under his "supreme direction," and the Grand Priory of

Germany adhered to these decisions; Hompesch's compatriots

wanted to lose no time in disavowing him.

These moves were the product of the

eccentric zeal of Czar Paul, exploited by the Order's envoy. Giulio Litta,

after his naval service in the Russo-Swedish War, returned to Russia in 1794

and acquired a favorite status with the new ruler. His doing was transforming

the Priory of Poland into the richly endowed Russian Priory. When in

recognition, Hompesch declared the Czar

Protector of the Order in August 1797, Litta was appointed ambassador

extraordinary to invest him with the title. It was obvious policy to make the

most of this welcome accession to the Order's support, and the character of the

new Grand Master showed how much the Order needed a strong prop in Europe.

Still, Litta used personal ambition to take his favor in a dangerous

direction. In November 1797, he made a speech declaring that the Order of Malta

wished the Czar to put himself at its head. In the months before the fall of

Malta, he was assiduously pressing Hompesch to

send the Emperor the most precious relics and to invest the largest possible

number of Russian noblemen with the cross of the Order. He encouraged Paul in

his plan to supplement the enlarged Russian Priory with a new one designed to

receive the Orthodox nobility of the empire, a body difficult to include in a

religious order of the Catholic Church. The nominal re-admission of the Grand

Bailiwick of Brandenburg a generation earlier provided a precedent for this

oddity. Hompesch approved the foundation on

the eve of Bonaparte's appearance off Malta, although the French attack prevented

the bull from being despatched to Russia.

In these irregularities,

Giulio Litta was seconded by his brother, Archbishop

Lorenzo Litta, who was in Russia as a papal nuncio. In that capacity,

Monsignor Litta represented a power as much in jeopardy from the

Revolution as the Order of Malta. The French armies had entered Rome, and by

1798 the aged Pius VI was an exile, first at the Charterhouse of Florence and

then in France, where he died. The nuncio, looking at potential saviors with

not too critical an eye, gave his full support to the abuses that followed.

The finishing touch to the Czar's assumption of power

was given when on 27 October (Russia) and 7 November (Western), he arranged

what he called his election as Grand Master. This was an acclamation made in St

Petersburg by a few knights (thought to have been between seventeen and

twenty-six), most of whom were Russian subjects, including

Giulio Litta and two French emigres. There is no need to labor the

illegality of the act. A single Grand Priory, even with three supernumeraries

from outside, had no power to elect a Grand Master, and, as all writers have

pointed out, the Czar was triply disqualified from the office as being not

professed, not celibate, and not a Catholic. But on 29 November / 10 December,

he was enthroned as Grand Master by the papal nuncio himself.

Giulio Litta, renouncing his vows with indecent haste, had already been

rewarded with the hand of a rich Russian princess, a niece of Potemkin, and he

was appointed Lieutenant of the Order, while his brother was made Grand

Almoner.

It remained to secure European

recognition. Louis XVIII of France (he had assumed the title on the death of

the child Louis XVII in the Temple) was an exile in Russia, and in January 1799

he authorized the French knights to recognize Paul. The Prince de Conde, head

of a cadet line of the Bourbons, was commander of the French emigre army, which

was now in the Russian service; he had been made Grand Prior of the Russian

Catholic Priory in November 1797 and was in no position to oppose his patron.

Louis' nephew, the Due d' Angouleme, who as a boy had held the Grand Priory of

France, tried to evade the question when it was put to him, and replied that

his forthcoming marriage excluded him from the Order, but he did not avoid

enraging the Czar, who had to be appeased by the Bourbon king with the grant of

the Saint-Esprit.

The Elector Charles Theodore of Bavaria,

whose Priory was his own foundation, was reluctant to recognize Paul, but he

died in February 1799, and Bavaria was inherited by a distant line of the

family hostile to every aspect of his rule. The new Elector determined to

abolish the Bavarian Priory, but a threat of Russian military invasion called

him to heel. The Kings of Naples and Portugal also gave their consent. The

German Emperor, as the ally of Russia, had little option but to follow suit,

and put pressure on Hompesch to abdicate

from the shadowy rule he maintained in Trieste. The great exception was Spain,

which was still in alliance with France, but here the question was whether the

Priories were to remain attached to the Order at all. After the fall of Malta,

King Charles IV had wasted little time in beginning the process of assimilating

the Order of Malta to those of Spain as a national order under royal rule. On 4

September 1798, he published a decree forbidding his subjects to have dealings

with the exiled Convent in Trieste, and there was no chance of his recognizing

the self-appointed one in Russia. The Spanish ambassador absented himself from

Czar Paul's coronation as Grand Master - and was promptly ordered out of the

country.

The ruler whose view was of most legal

relevance was the Pope. Despite the dire captivity to which he was reduced,

Pius VI could not bring himself to recognize a schismatic as head of a Catholic

religious order. He temporized, and when he finally wrote to

Monsignor Litta on 11 March 1799 disapproving of the election, he

authorized him to delay communicating the decision to the Czar. But an

indiscretion brought the letter to Paul's ears, and his response was immediate.

The Bali Litta was dismissed as Lieutenant (his place in the imperial

favor had already raised against him a cabal of Russian magnates, led by

Count Fedor Rostopchin) and his brother the

nuncio was told to leave St Petersburg.

By this time the Czar had founded the

projected Orthodox Priory of Russia, with ninety-eight commanderies and a

revenue of 216,000 roubles, and with his eldest

son, the Czarevich Alexander, as its Grand

Prior. Paul entrusted special squadrons of the Baltic and the Black Sea fleets

to the Knights of Malta. He also added ten commanderies to the Catholic Priory,

which by 1799 included a hundred French emigres among its knights.

Next to Litta,

the guiding hand in these developments was Joseph de Maisonneuve, an ambitious

knight who had been active since the 1780s in the plans for the Grand Priory of

Poland. Appointed the Order's Master of Ceremonies in Russia, he quickly published

an outspoken account of the recent events, reflecting the bitter anger of the

French knights at the way the Order's honor had been betrayed by Hompesch, and their hopes of vindication under the Czar.1

Outside Russia, a

leading figure in the Order's affairs was Johann Baptist von Flachslanden.2

Originally a member of the Priory of Germany, he had played an important role

in the foundation of the Bavarian Priory and the Anglo-Bavarian Langue, to

which he transferred his membership, and he was rewarded with the Bailiwick

of Neuburg and the office of Turcopolier. As an Alsatian, and

therefore a French subject, he was elected to the Estates General (a general

assembly representing the French estates of the realm) of 1789. In July 1799 he

represented the usurping Grand Master in the agreement made with the Elector

Maximilian Joseph of Bavaria, and in November he headed a Bavarian deputation

to Russia which presented the homage of its Grand Priory. As Turcopolier in

1799, he was one of the only two legitimate Piliers of

the Order who remained in office under Paul I. The other was the Bailli

de Ferrette (Baron von Pfordt-Blumberg),

who was also Alsatian. He had succeeded Hompesch in

1797 as Pilier of the German Langue, and

was to be important in the Order's affairs as a diplomat until his death in

1831. He continued under Paull as Grand Bailiff, while all the other great

offices were assigned to Russian subjects appointed by Paul. However, by 1801

both Flachslanden and Ferrette had

been dropped, and the Russian governing council did not contain a single

professed Knight of Malta.

But while Tsar Paul I’s appointment was to be

contested by Pope Pius VII and numerous Priories of the Order, as has been

seen, recognition or non-recognition of the Czar was a decision of the various

rulers; most of the knights could do little but obey their sovereigns' wishes.

In Italy, the Bali Trotti refused to accept Paul l and was

immediately deprived of his commandery 3, but there were not many who saw their

duty so clearly. If we ask why professed Knights of St John should have been

prepared to accept Czar Paul as their head, we should seek the reason in the

prompt remedy it offered for the loss of Malta. Within seven weeks of the

island's surrender, Nelson had destroyed Bonaparte's Egyptian expedition at the

Battle of the Nile. In September the Maltese rose against the French occupying

forces, whom they held besieged for two years in Valletta, with rather feeble

support from the British Navy, until their final capitulation in September

1800. The official British policy during this period was to give back Malta to

the Czar, as Grand Master of the Order. Such an outcome offered a means - and

the only means - whereby the Order could have quickly wiped out the stain

of Hompesch's surrender, and it is

understandable if the knights thought that accepting a schismatic as Grand

Master was not too high a price to pay for it. That must have been the feeling

of the many French knights who placed themselves under the rule of Paul I. In

December 1798 the Czar ordered a Russian fleet through the Dardanelles, and

during the next twenty months it would have been possible for this force to

sail to Malta, clinch the siege and claim the island for the Czar. It is one of

the oddities of Paul's policy that it never did so. The fleet's first

objective, sensibly enough, was the Ionian Islands, which were recaptured from

the French. By September 1799 the fleet had arrived in Sicily, and Nelson even

offered to transport its sailors and marines to Malta, after its ships were

pronounced unseaworthy for the journey. The Neapolitan government, however,

contrived to keep it in Palermo. In January 1800 it returned to Corfu, as the

Czar's policy changed towards a rapprochement with republican France, and it

withdrew from the Mediterranean later in the year.

For several months after the Russian

coup d'etat, the Grand Master Hompesch refused

to accept his demotion. He had formally reconstituted the Convent in Trieste on

27 September 1798, and he appointed a Sacred Council, which issued instructions

to the few who were willing to receive them. However, with his own sovereign

supporting the usurpation, his position became untenable. At the Emperor's

insistence, he signed an act of abdication on 6 July 1799; a few days later he

left Trieste, abandoned by all, and took up residence in the chateau of Portschach in Carniola, a property of the Bishop

of Laibach. The Convent of the The Knights

of Malta Order was dissolved, not to be reconstituted till four years later in

Messina. To be canonically valid, the Grand Master's abdication needed papal

acceptance, but Pius VI, in captivity in France, died the following month, and

the papacy remained vacant until the election of Pius VII in March 1800. Thus

even the knights of the Grand Priory of Rome, with no direction of their own

ruler to guide them, had no government to look to but that of Paul I.

During all this time, the long siege of

the French garrison in Valletta was continuing.

Many of the Maltese would have welcomed

the return of Hompesch, whose popularity in the

island was the only achievement of his Grand Magistry.

If he had had a spark of enterprise, he might have trumped Paul I's card at any

time from September 1798 by returning to Malta and putting himself at the head

of the national revolt, with as many of the knights as were prepared to support

him. But he proved himself as spineless in recovering his throne as he had in

preserving it. He sent an emissary to Malta in June 1799, not to range himself

with the resistance but to parley for retrocession with the French garrison,

whose position by then was doomed. When Valletta finally fell in September

1800, the Czar claimed Malta from the British; but his flirtation with Bonaparte,

who had seized power in France as First Consul, was beginning to sow seeds of

suspicion in the mind of the government of London, and it made no reply. Paul

responded by forming the League of Armed Neutrality and planning to recover

Malta through alliance with the French.

The Czar's eccentricities were raising

alarm among his closest servants. His infatuation with the Order of Malta led

him to shower its cross on all who took his fancy, including his mistress,

Madame Lapoukhine. When she fell from favour, the Czar used to call nightly on her successor,

Madame Chevalier, attired in the Grand Master's habit which he had designed for

himself. By the early months of 1801 Paul was leading a life of fearful

isolation in his moated palace of Mikhailow,

while his ministers plotted to assassinate him, in collusion, it was thought,

with the Czarevich himself. His Prime

Minister, Count Peter von der Pahlen, who had

been made Grand Chancellor of the Order of Malta, was at the head of the

conspirators. On 12 / 23 March 1801 the Czar was strangled by a group of his

courtiers, among whom were four of his own Knights of Malta.

The young Alexander I, as he took the

throne in these macabre circumstances, had no part in his father's mania for

the Order of Malta, and he resolved to divest himself of its government. The

distinguished soldier Marshal Soltykoff had

been appointed Lieutenant by Paul on the dismissal of Litta, and he was

continued in office for the moment, but the new Czar's policy was to restore

the Order to its constitutional norms. In its shattered state, it would be

impossible to elect a Grand Master in a statutory way; so Alexander proposed,

with notable disinterest, that the Pope should appoint one from candidates

nominated by the Priories of the Order that still remained. This remedy,

however, was delayed by the continuing war in Europe and in particular by

uncertainty over the fate of Malta, now in British hands. In March 1802 peace

was restored by the Treaty of Amiens, which provided for the return of Malta to

the Order of St. John. So as to avoid control by either of the main

belligerents, the treaty stipulated that French and British subjects should be

excluded from the Order. As a result, the Anglo-Bavarian Langue was renamed the

Bavaro-Russian, although in practice the only knights of British blood in the

Order were a few individuals who had joined the French Lanques.

The three French Langues were, to be deemed

abolished. As the Order of Malta was not a signatory to the Treaty of Amiens

(which in any case never took effect), it was not bound by a clause that

changed its constitution, and the exclusion of the French Langues was to be recognised as

obsolete even before the Treaty of Paris in 1814, which superseded that of

Amiens.

In any case, the provisions for the election

of a Grand Master were sabotaged by the two rulers with the most influence in

the matter. In January 1802, even before the Treaty of Amiens was Signed, the

King of Spain made definitive the separation of his four Priories and declared

them a national Spanish order. Thus, with the exclusion of the French, only

eleven Priories were left to give their votes for a Grand Master: Venice, Rome,

Capua, Barletta, Messina, Germany, Bohemia, Bavaria, the two Russias, and Portugal. Next, Bonaparte intervened in the

choice: the Bailli Flachslanden, who had been

nominated by Bavaria and the two Russian Priories, was vetoed outright, as an

active Royalist. Having described the plans for Malta as "a romance that

could not be executed", Bonaparte urged Bavaria to a second attempt at

abolishing its Grand Priory, though Russian protection proved strong enough to

save it for the moment. In August Bonaparte sought to limit the Pope further by

excluding a Neapolitan subject and urging the choice of a Roman, a northern Italian

or the innocuous Bavarian knight Tauffkirchen.

In the meantime, Hompesch had been aroused from the state of apathy

into which he had fallen after his abdication. In late 1800 he moved from

Austria to the Papal States, where he lived for the next four years. The death

of Paul I encouraged him to revive his claims; he asserted that his abdication

had been dictated to him by Austria and that it had merely been a proposal of

abdication. Britain, however, was not prepared to give Malta back to the

knights under Hompesch, and Bonaparte also

rejected him so as not to imperil the session.

The new Pope, Pius VII, although he had

been elected in Venice during the French occupation of Rome, was now back in

his capital and trying to reach a modus vivendi with the post-revolutionary

system of Europe. His choices with regard to the Order of Malta were limited.

He could have declared that Hompesch's abdication

had never been accepted and that he was therefore still Grand Master, but in

the circumstances, that option was not considered. The Pope tried to recover

the Order provisionally for Catholic control by naming a Lieutenant in the

person of the Bali Giuseppe Caracciolo, who by Paul I's appointment was

serving as the Order's ambassador to the Court of Naples; but as Soltykoff refused to hand over authority to him the

nomination remained without effect. The Priory of Rome had so far abstained

from electing a candidate for the Grand Magistry so

as to leave the Pope's choice untrammeled. Finally, in August 1802, the Pope

resolved to appoint Prince Bartolomeo Ruspoli (1754-1836),

a member of a great Roman family, who for form's sake was declared the

candidate of his Priory. He was chosen as being likely to secure Bonaparte's

approval, which was duly given. Pius VII, therefore, offered him the

Grand Magistry in a brief of 16 September,

which by alluding to Hompesch's abdication

constituted the first, though tacit, papal recognition of that act.

Ruspoli was a devout and cultivated but eccentric man,

who indulged a taste for incessant travel, He was currently thought to be in

London, whither the papal offer was sent; in fact, he proved to be making a

tour of Scotland and was not to be found; in mid-November Ruspoli had still not returned to the capital. By

early December he was considering the proposal without enthusiasm. His

response, setting difficult conditions, may have been aimed at securing the

explicit support of the Spanish Crown. He demanded that British and Sicilian

troops be withdrawn from Malta before his arrival as Grand Master, that the

Spanish Priories be reunited to the Order, and that Spain should pay its

arrears from the four years of separation. By 28 December the British government

had rejected Ruspoli's conditions with

regard to Malta, and he sent a reply to the Pope with his refusal to serve.

Not until February 1803 was the vacancy

in the Grand Magistry filled when the

Bali Tommasi accepted the office from the Pope, and Marshal Soltykoff, on hearing the news, finally handed over his

powers. He sent from St Petersburg the magistral regalia which had been created

by Paul I (they are now in the Magistral Palace in Rome, forming a memento of a

bizarre interlude in the Order's past).

The close of the Russian interlude

prompts an estimate of its significance in the history of the Order of St John.

One may begin with the legal aspect, which is not a matter of dispute. Paul I

was inherently incapable of being the superior of a religious order of the

Catholic Church, and his "election" in November 1798 was invalid in

itself. The legitimate head of the Order continued to be Hompesch until his abdication in July 1799, and

theoretically until the implicit papal acceptance of that act in September

1802. But in practice, there was no legitimate government of the Order from

July 1799 until February 1803, when Tommasi took charge. There was

also no legitimate Convent of the Order during that period, for the officials

appointed by Paul I were non-professed and nearly all non-Catholics.

We ought, however, to consider what

Paull's seizure of power meant in practical terms, and from that point of view,

we may judge that he saved the Order in the hardest predicament of its history.

One need only consider what would have happened if Hompesch had

continued as Grand Master. The Order would probably have fallen apart, with

many knights and whole Priories calling for his deposition. Certainly, there

would have been little chance of the British government, or anyone else,

wishing to see Malta returned to the knights under Hompesch's rule.

Paull's de facto Grand Mastership restored political credit to the Order at a

time of unprecedented disgrace; it is unlikely that Britain would have agreed

to restore Malta to the knights in 1802 but for the fact that it had previously

been envisaging returning it to Paul I; and the Czar's rule, illegitimate

though it was, effectively marshalled the whole Order under one government,

with the single exception of Spain, so that when Tommasi became Grand

Master in 1803 he took over a united Order, and not the chaos of conflicting

factions into which it would have descended if Hompesch had

not been promptly disposed of.

Nevertheless, after Paul I the position

of the Order in Russia is worth noting.

Its status as Paul I had left it was

undone by Alexander I in 1810 when he confiscated the general possessions of

the Catholic and Orthodox Priories, but the Order continued after a fashion. It

received a further blow from the death in 1816 of Marshal Soltykoff, who had been the only member of the Russian

nobility who retained a real interest in it. In 1817 Alexander decreed that the

family commanderies should become extinct on the deaths of their current

holders, and forbade the wearing of the Order's cross without imperial

permission. Thus the Priory indeed may be said to have become extinct at this

time, or at least at the death of its surviving commanders.

Yet the Bali Litta continued

to call himself President of the Catholic Priory and remained a well-known

figure at the Russian Court until his death in 1839. In 1820 he reported to the

Bali Miari that commanders' revenues were still being paid by the

State, the Order's churches were maintained, and the government held a capital

of more than 2 million roubles, which legally

belonged to the Order. Even more interesting are the documents which he sent

to Miari in 1818 relating to the unrealized plans to restore the

former Grand Priory of Poland, a dossier that reveals the Czar's active

interest in preserving the Knights of St John in his dominions.4 These letters

show that Russia was one of the countries where the Order would have had a good

chance of restoration if its leaders had been able to raise it from impotence

and obscurity.

1. Joseph de Maisonneuve, Annales

Historiques de l'Ordre Souverain de Saint Jean de Jerusalem (1799).

2. On Flachslanden see

Thomas Freller, The Anglo-Bavarian Langue of the Order of Malta (Malta,

2001). The author corrects Flachslanden's date

of death, which was previously given generally as 1822.

3. Archives of the Order of Malta in the

Magistral Palace in Rome, GM 108, Trotti to Busca,

19 December 1829.

4. Archives of the Order of Malta, GM

92, Litta to Miari, 31 January 1820, and GM 93, dossier of 27

March 1818 etc., accompanying Litta's letter to Miari, 7/19 May

1818.

For updates click homepage here