By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Ourselves having

extensively covered the making of the Middle East

recently expert

historian James Barr commented that there are odd similarities with the

situation exactly a century ago. "Iraq was under British military

occupation, but the British government, just like the Americans more recently,

wanted to withdraw its troops. An outside force, then it was Arab nationalists

based in Syria, was plotting violence that it hoped might quicken Britain’s

exit."

The revolt that

convulsed Iraq in 1920 was a taster of the consequences of three irreconcilable

promises the British had made during the First World War, which became apparent

over the next ten years. Under pressure in 1915, they had sent Mecca’s ruler Sharif

Hussein a weasel-worded letter that recognized his

claim to an empire encompassing Iraq and Syria if he rose up against the Turks.

In 1916, in the Sykes-Picot agreement, they then secretly pledged a northerly

wedge of this same territory to the French, to patch up the entente cordiale.

However, the fall of

the Ottoman Empire, which ended at a stroke thirteen hundred years of

imperialism in the Middle East, was not a necessity, let alone an inevitable,

consequence of World War I. It was a self-inflicted disaster by a shortsighted

leadership blinded by imperialist ambitions. Had the Ottomans heeded the

Entente's repeated pleas for neutrality, their empire would most likely have

weathered the storm. However, they did not, and this blunder led to the

destruction of the Ottoman Empire by the British army and the creation of the

new Middle Eastern state system on its ruins. Even this momentous development

was not inevitable, and its main impetus came not from the great powers but a

local imperial aspirant: Sherif Hussein ibn Ali of the Hashemite family.

The Sherif

exemplified the complexity among Arabs. Before the war, Hussein had been

detained in Istanbul under the caliph, Sultan Abdul Hamid II hastily conferred

to him the title of the emir of Mecca and Medina in the Hejaz in order to

prevent the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) from appointing its own

crony. In 1909 the sultan was overthrown, and Istanbul’s relationship with the

Sherif deteriorated. The revolutionary triumvirate was eager to assert

political control over the Hejaz and extend the rail links into the Emirate,

largely to be able to deploy troops more rapidly there if required. The Sherif

opposed the changes, ostensible to protect the incomes of camel rovers who

carried the pilgrims to the holy places, but his motives were revealed in a

secret meeting in the spring of 1914 between his son, Abdullah, and the British

Consul General of Egypt, Lord Kitchener and his secretary, Ronald Storrs. The

sheriff and his sons, while eager to resist Istanbul, by force if necessary,

needed British intervention in an internal matter of the Ottoman Empire,

although Abdullah knew the British had arranged to become a protector of the

Emirate of Kuwait in 1899, had asserted their influence over the Gulf States in

1903 with a series of high-profile diplomatic overtures, and, ultimately, had

made the military intervention against Egypt in 1882 which had led to the

long-term occupation of what was still, ostensible, an Ottoman domain.

When the war with the

Ottomans was imminent that autumn in 1914, Storrs and Kitchener advocated

restarting the negotiations, asking the sheriff to declare any Ottoman fatwa of

jihad against the Entente to be illegitimate. At the same time, the Ottomans sought

the sheriff's endorsement for their declaration of holy war. Sherif Hussein

hesitated: he gave his personal endorsement for their declaration of holy war

but avoided public declaration on the grounds that it would invite aggression

by the Entente powers against Muslims. The disappointing response prompted the

government in Istanbul to claim the sheriff had approved of the call to jihad

anyway, but they also sought ways to neutralize the sheriff and his Hashemite

family.

Meanwhile, Storrs

offered an alliance with the sheriff if he would promise to support the British

war effort. In return Kitchener, as newly appointed Secretary of State for War,

was prepared to offer ‘independence’ to the Arabs in the Hejaz. While ensuring

their safety and freedom from the Ottomans, what Kitchener had in mind was a

caliphate that was spiritual in nature, not political.

Hussein delayed,

knowing that he could not yet guarantee that many would follow him and also

that the Ottoman forces in the region would follow him and also that the

Ottoman forces in the region were strong enough to crush any premature revolt.

Moreover, his ambitions were initially unclear. It was only later, once the

British had begun to secure their position in Palestine, that Hussein began to

consider a role as a leader.

Far from being a

proto-nationalist struggle for the sake of Arabism, this was a bid for dynastic

security and an opportunity to replace the secularists in Istanbul with a

caliphate of his own.

Concurrently with

Sherif Hussein’s planning was the conspiracy of Al Fatat a Syrian secret

society which had been founded one year before the war. Al-Fatat was the

civilian equivalent of the militarydominated al-Ahd

(the Covenant). This group's membership was limited largely to army officers.

It advocated the establishment of autonomous entities for all ethnic groups

within the empire; each group was to be permitted to use its native language,

although Turkish would remain as a lingua franca. AI-Ahd maintained a central

office in Damascus. After the outbreak of war, the two movements would merge.

Al-Fatat approached

Hussein to enquire whether he would lead the movement against the CUP

government in Istanbul. Hussein again hesitated, but the discovery in February

1915 of Ottoman plans to have him arrested and executed compelled the sheriff

to act. He sent his son Faisal to gather intelligence about the groups in

question.

Meeting the

conspirators, Faisal discovered that the nationalists were concerned that, if

the Ottomans were defeated, the French would make a bid to take over Syria, yet

they were reassured by news of secret talks between Faisal’s brother, Abdullah,

and Kitchener.

Al-Fatat thus drew up

their own plans, defined in the Damascus Protocol. Thy desired an alliance with

Great Britain, to provide military and naval protection, and accepted the

principle of economic preference for the British Empire. In June 1915, these plans

and the Ottoman demands were considered by Hussein and his sons, before being

presented as terms for cooperation with the British at Cairo. In exchange of

letters, the Hashemites claimed to represent the ‘Arab nation’.

The British reaction

was to dismiss this extensive claim to represent the Arab ’nation’, but there

was some sympathy of a Sherifian revolt that might

potentially tie-down thousands of Ottoman troops.

The Sykes-Picot agreement

Sykes-Picot are often accused of having divided up the Arab world,

but as we have seen elsewhere Mark Sykes may have actually believed that his

actions had the best interests of the Arabs at heart. He believed that, if

properly encouraged, it would be possible to reawaken among the Arabs memories

of a vanished greatness and bring them closer to the community of nations.

While the carnage at

Gallipoli mounted day by day, Sir Mark Sykes was

dispatched by the War Office to visit British commanders, diplomats, and

imperial officials throughout the eastern theatre of war.

In a telegram to Sir

Percy Cox in which Sykes claimed that the king "and his son are really

very moderate in their views", and suggested that ‘if Ibn Saud could by

some means convey to Sherif that he regards him as the titular leader of Arab

cause without in any way committing his own local position I believe much good

would result’. Cox, however, declined to approach Ibn Sa’ud

on the subject. He telegraphed to the India Office that he did not see his way

to comply with Sykes’s re-quest without Ibn Sa’ud questioning

his ‘bona fides’. On 26 December 1915, Cox had concluded the Treaty of Darin

with Ibn Sa’ud. In this treaty, Great Britain

recognized the Najd’s independence, promised assistance in case it was attacked

by a foreign power, and granted Ibn Sa’ud a subsidy

for his military campaign against Ibn Rashid, the Emir of Ha’il,

who was loyal to the Turks. On the day of the signing of the treaty, Ibn Sa’ud had characterized Hussein to Cox as ‘essentially

unstable, trivial, undependable’.

David George Hogarth

(Member of Arab Bureau) and Harry St John Bridger Philby (British Arabist and

colonial office intelligence officer) in turn reported on Hussein’s attitude

towards Ibn Sa’ud. Hogarth did not deny that to

Hussein ‘Arab unity’ meant ‘very little […] except as a means to his personal

aggrandizement’, but saw some merit in Hussein’s point of view in the question

of his title. The king was moreover too weak to risk an armed conflict with Ibn

Sa’ud:

He both fears Ibn Sa’ud as a center of a religious movement, dangerous to the

HEJAZ, and hates him as irreconcilable to his own pretensions to be ‘King of

the Arabs’. This latter title is the King’s dearest ambition, partly no doubt,

in the interest of Arab unity, which he constantly says, with some reason, can

never be realized until focused on a central personality. He opposes to our

argument that he cannot be ‘King of the Arabs’ till the Arabs, in general,

desire him to be so, the counter-argument that they will never so desire till

he is so-called […] The resultant situation, however, is that the King is very

unlikely to provoke a conflict with Ibn Sa’ud while

the European War lasts. He is not easy in his mind either about Central Arabia

or about the loyalty of his own Hejaz people […] He is quite firm in his

friendship to us, but none too firm on his throne.

The most immediate

problem, however, arose from the clash between the promises to Hussein and the

French.

Enter the French

On 1 September 1916,

a French mission arrived at Alexandria on its way to the Hijaz. It was headed

by Colonel Edouard Brémond who earlier had been a success

in French Africa. However, it was not as a soldier that Brémond

would establish a reputation in the Hijaz. He did not conceal from his British

interlocutors that Hussein’s revolt should not grow into something bigger than

the local affair that it was.

The Foreign Office

refused to take the matter very seriously. Although Charles Hardinge, 1st Baron

Hardinge of Penshurst who served as Viceroy and

Governor-General of India was now prepared to admit that Brémond

had shown himself to be ‘unreliable and untrustful’, the forthcoming mission by

Sykes and Georges-Picot would soon set matters right, the more so as Picot had

told Sir Ronald Graham that he intended to assume control of affairs in the

Hijaz. The instructions of Sykes and Georges-Picot constituted a faithful

reflection of the Foreign Office’s policy towards the Middle East, with which

Sir Mark completely identified. Everything turned on cordial relations between

France and Britain. British diplomacy should spare no effort to accommodate

French susceptibilities, whether these were justified or not. This was the

reasoning behind McMahon’s convoluted formulations in his letters to Hussein in

the autumn of 1915. This also explained the procedure of first coming to an

agreement with France before the negotiations with Hussein could be finalized.

This did not mean that Grey, Sykes, and Foreign Office officials were blind to

the problems that this policy entailed, but these counted for little compared

to the all-important objective of good relations with France. Foreign Secretary

Arthur James Balfour'sBalfour’s minute on Wingate’s

dispatch on Brémond’s machinations, however,

indicated that he was less attached to this orthodoxy: ‘I think if the French

intrigues go on in the Hedjaz we shall have to take a strong line. They may

find us interfering in Syria if they insist on interfering in Arabia.’

Balfour’s minute

constituted a first indication that British Middle East policy would change

after Grey had left the Foreign Office. This was for the greater part due to

the increasing meddling in foreign affairs by members of the War Cabinet, Prime

Minister Lloyd George in particular, as well as the establishment of the

interdepartmental Middle East Committee, subsequently the Eastern Committee,

chaired by Curzon. Balfour dominated British foreign policy-making to a far

lesser extent than foreign secretary Edward Grey had done in his days. In the

early spring of 1917, matters still hung in the balance. For the time being Brémond could continue to make a nuisance of himself in the

Hijaz. The Failure of the ‘Projet d’Arrangement’ Sykes’s

arrival in Egypt heralded the reversal of the Foreign Office’s attitude towards

the complaints from Cairo about the French mission. From that moment on these

were no longer treated as utterances by biased men on the spot who tried to

blow up incidents to further their own Syrian ambitions. On 8 May 1917, Sykes –

who at the beginning of March had already written to Wingate that he had ‘seen

the George Lloyd correspondence and George Lloyd, truly Bremond’s performances

have been disgusting’– telegraphed to Graham that after a careful investigation

he had reached the conclusion that ‘the sooner French Military Mission is

removed from Hedjaz the better’. The ‘deliberately perverse attitude and

policy’ on the part of Brémond and his staff

constituted the main obstacle in the way of Sir Mark’s attempts to improve

relations between the French and the Arabs.

If the French

position was not challenged, then the door was wide open to, as Ronald William

Graham (worked at the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office, before moving

to Cairo as a Counsellor) had formulated it in November 1916, ‘the reversal of

our policy of the last 100 years which has aimed at the exclusion of foreign

influence on the shores of the Red Sea’. According to Sir Ronald: We can admit that no European Power should

exercise a predominant influence in the holy places. But the French note goes

much further than this in laying down that no Power is to obtain new territory

or political prestige in Arabia and in limiting French recognition of our

special position there to commercial interests. Hitherto the French have always

recognized our special political position […] I fear we must conclude that the

French desire to go back on this attitude and to claim equality of political

position with us in Arabia – when they had no position at all and owe any

improvement that they have latterly achieved in this respect entirely to our

help and influence. Such a submission, which is a poor return for our rapport,

must be strongly resisted.

Fear of French

dominance and the need to establish an alliance that would support his

political ambitions led Faisal to initiate the United States’ Middle East

initiative. The inquiry was, in part, a result of the Hashemite prince’s choice

not to reject the fresh mandates system outright while in Paris—a decision that

immediately generated much controversy within nascent nationalist circles

across bilad al-sham, or Greater Syria.

Lloyd George and the

British believed that, in Faisal and his Arab irregulars, they had an ace in

the hole, a façade to rule behind.

Anticipating this

very track, the French press sought to undermine Faisal’s Arabs by playing up

Lawrence’s role in leading them. Astonishingly, in light of his later rise to

world fame, Lawrence was entirely unknown to the Western public before the end

of the war, largely by design. Both Allenby and his chief political officer,

Gilbert Clayton, had concealed Lawrence’s role in public communiqués so as not

to compromise Faisal’s political prospects. As late as December 30, 1918,

Lawrence was unmentioned in the account of the fall of Damascus published in

the London Gazette. It was actually a French newspaper that first broke

Lawrence’s 'cover,' expressly to belittle Faisal’s Arabs. Colonel Lawrence, the

Echo de Paris reported in late September 1918, riding at the head of a cavalry

force of "Bedouins and Druze," had "sever [ed] enemy

communications between Damascus and Haifa by cutting the Hejaz railway near

Deraa," thereby playing "a part of the greatest importance in the

Palestine victory."

By introducing T. E.

Lawrence to the world, the French scored an own goal of the most

self-destructive kind. Seeking to undermine Faisal, the Echo de Paris had

instead glorified Faisal’s greatest champion, a man born for the role of

mythmaker. Rather than deny his role in the Arab revolt, Lawrence shrewdly

manipulated his newfound fame, presenting himself not as an effective liaison

officer who had helped Arab guerrillas blow up some railway junctions but as a

witness to an Arab national awakening.

But the French were

in no position to oust Feisal, the British tried not to take sides, and

Anglo-French relations deteriorated. By January 1920, however, the British had

begun to wonder if continuing to sit on the fence was wise.

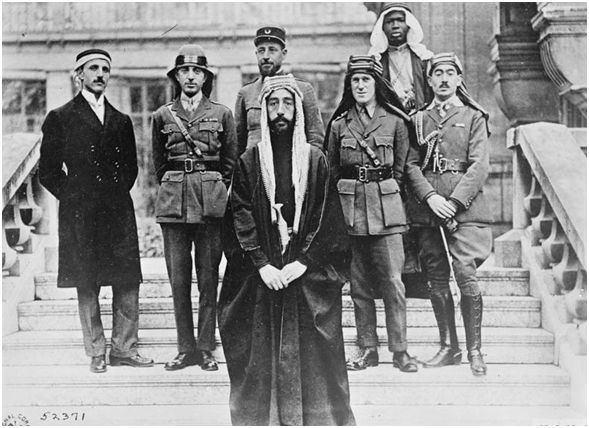

Below Faisal's (also

called the Arabian Commission) delegation at Versailles, during the Paris Peace

Conference of 1919. Left to right: Rustum Haidar, Nuri as-Said, Prince Faisal,

Captain Pisani (behind Faisal), T. E. Lawrence, an unknown member of his delegation,

Captain Tahsin Kadry:

Following the 1918 Paris Peace Conference

As the talks were

underway in Paris, Ibn Saud took the opportunity to attack his Hashemite rivals

and make a bid for control of the Hejaz. Saud was angered by the pretensions of

Hussein, not least the claim to be ‘King of Arabia’, and irritated by the Hashemite

edicts in Mecca. There had already been skirmishing between the Saudis and the

Hashemites, but, in May 1919, Ibn Saud despatched

10,000 cavalry and 4,000 well-armed dismounted men to inflict a decisive defeat

on Hussein. The situation revealed the difficulty for Britain in arming and

financing two rival factions over the war years. The Foreign Office had backed

the Hashemites, while the Government of India had funded the Saudis. Without a

common enemy, the conflict between the Arabs had increased in likelihood, and

the negotiations in Paris were not keeping pace with events on the ground.

Faisal's ( brother

Abdullah tried to halt the Saudi offensive but was defeated and his army

routed. As they streamed westwards, the Foreign Office was forced to issue an

ultimatum to Ibn Saud. If he did not withdraw, the Royal Air Force would be

sent to interdict his army. The India Office too urged Ibn Saud to withdraw.

Lawrence was nevertheless perplexed. He had assured the Foreign Office that if

Saud threatened the Hejaz, the Hashemites would be able to deal with it.1 The

fact that the Hashemites had suffered such a comprehensive defeat undermined

not only his own credibility but his claims about the Hashemite capability to

govern Syria.

It was the Americans

who provided a new opportunity for the Hashemites to achieve their objectives,

when, thanks to President Woodrow Wilson’s insistence, there was to be a

commission of inquiry into local allegiances that would help fulfill the

principle of self-determination. The British offered Sir Henry McMahon and

David Hogarth to accompany the American officials, Dr. Henry King, and Mr.

Charles R. Crane, to the region, but the French refused to send any delegates.

After two months of delay, imposed deliberately by the Quai D’Orsay, the

British gave up. The Americans went ahead on their own and returned with the

recommendation that there should be mandates, care-taker administrations, for a

limited period, for Syria, Palestine, and Iraq. King and Crane recommended an

American mandate for Syria, Britain in Iraq, but none for the French. They also

recommended that the Zionists should abandon any idea of a ‘commonwealth’

within Palestine, as the British had suggested in 1917.2 All sides, including

the American administration, ignored these findings and continued to negotiate

on their own terms.

The hard fact was

that Britain now in 1919 wanted a firm alliance with France for future European

security arrangements, and that meant cooperation with them over their stated

interests in the Middle East. France was determined to govern Syria, regarding

it as an essential base to balance Britain’s dominance in the Eastern

Mediterranean. They regarded it as the only suitable compensation for

long-standing humiliations over Suez, Egypt, and the Sudan, where Britain had

thwarted French interests for 40 years. The problem for Britain was that its

model of governance was so different from that of France. While the British

sought local intermediaries to govern, under British protection, for some

mutual economic advantage, the French insisted on a political, linguistic and

military subordination. Lawrence urged the British model, claiming: ‘If the

French is wise and neglect the Arabs for about twelve months, they will then be

implored by them to help them.’ He continued: ‘If they are impatient now, they

will only unite the Arabs against them.’3

Feisal had already

resolved not to accept any French proposal, from the British or directly from

the French, about the future of Syria. Faisal left

Paris to consult the Syrians.

Leading up to the famous San Remo Conference

In February,

discussions at the London Conference had virtually awarded the Syrian mandate

to France. His hand was forced by Syria’s March 8 Declaration. It broadcast to

the world that a majority of Syrians favored national independence, a fact that

the British had tried to cover up by suppressing the King-Crane report.

Curzon’s aide, Hubert

Young, favored a compromise: Britain could insist on the Supreme Council’s

sovereignty over the future of Syria and at the same time signal respect for

consent of the governed by promising Faisal’s rule under the mandate. A

thirty-five-year-old former soldier, Young had witnessed Faisal’s entry into

Damascus in October 1918 and remained one of his strongest supporters at the

Foreign Office.1

Young later published

an account of the crisis that Curzon faced in his negotiations with the French:

When the news reached

London the French Ambassador immediately asked for an interview with Lord

Curzon. There was a meeting of the Conference of Ambassadors in Lord Curzon’s

room that afternoon, and he said he would see the French Ambassador immediately

after it. I was in attendance at the meeting, and when tea was brought in after

the discussion I reminded Lord Curzon of his promise.

“But I don’t know

what to say to him,” Curzon replied.

Curzon and Cambon

subsequently agreed to send the joint message to Faisal refusing to recognize

his status as king or the legality of the Syrian Congress. The March 15 note,

conveyed by Gouraud, invited Faisal to Europe to

settle Syria’s future status, an act that would force him to recognize the

Supreme Council’s sovereignty over Syria.

Ultimately, Curzon

won support for his policy because of Syrians’ inclusion of Palestine in their

declaration, and the simultaneous declaration by Iraqis in Damascus of

independence in Mesopotamia. Zionists saw peril in ceding authority to the

Damascus government, and hard-liners in the India Office opposed any form of

Arab self-rule in Mesopotamia. All feared a slippery slope, if one occupied

people were granted sovereignty, then others would demand the same. As Young

later disclosed to the British parliament, the Foreign Office was forced to

accept a “parallélisme exacte”:

if Britain wanted a free hand in Mesopotamia, it had to accord France such

license in Syria.2

The Syrians might have

stood a chance of winning British and French support had they chosen to declare

only partial independence, of the East Zone in the Syrian hinterland. British

imperialists were angered that the March 8 declaration not only included

southern Syria, British-occupied Palestine, but also was accompanied by a

separate Iraqi declaration of independence. And French liberals could never

have prevailed against the colonial lobby to cede Lebanon. A partial call was

never a political option, however. Only half of the deputies who convened on

March 8 were from the East Zone. The other half came from Lebanon and

Palestine.3 Because the Syrian Declaration was an assertion of right and

principle, it would have been difficult to exclude some Syrians in favor of

others.

The announcement of

the establishment of mandates, ratified at the San Remo Conference in April

1920, caused widespread local anger. Small groups of Syrians started attacking

symbols of French authority, and violence escalated. The French Army used the opportunity

to issue an ultimatum against the Arab leaders in Damascus and marched on the

city. Lord Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, urged Faisal to accept the French

demands to avoid a conflict, and he did, but the Syrian nationalists did not. A

small detachment at Maysalun mustered to take on the

French Army but was defeated. Faisal was unceremoniously deported.

During the

negotiations in Paris, T. E. Lawrence came to believe the center of gravity in

Middle Eastern affairs was shifting towards Mesopotamia.4 In a period before

the discovery of oil reserves in Saudi Arabia, he assessed that Iraq would be

the most dynamic of the Arab regions. Syria, by contrast, he thought too

agrarian. That said, he did not think Basra would be as important as the

Government of India thought it might, and, perhaps in an effort to persuade

Europeans about the greater relative importance of the Levant, he emphasized

the ‘Mediterranean’ focus of all the Semite peoples. He hoped particularly for

Arab and Zionist cooperation, not least because he believed that Jewish energy,

industry, and finance would fuel the economic ‘take-off’ of the Near East and

thus the entire region. The survival of the British Empire, he reasoned, needed

the cooperation of local people for its governance and security. Like most of

his generation, he imagined dominion status, and equality within the empire, of

all the colonies.5

The military

occupation of Mesopotamia had continued after the war, and it was administered

as an enemy territory until the establishment of the British civil government

under Sir Arnold Wilson, with the close support of Gertrude Bell.6 The

arrangement frustrated those Arabs who had hoped for independence, and the

announcement of the conclusions of the San Remo Conference, which made the new

state of Iraq one of the mandate territories, sparked mass demonstrations. Many

Iraqis feared that, despite wartime assurances of liberation, the British

intended to turn the country into a colony. Protests were led by prominent

religious figures and often orchestrated by tribal elders or former Ottoman

Army officers. Their protests were emboldened when it became evident that

British troops were being withdrawn and demobilized. The proportion of British

officers in the Iraq garrison was also lower than usual since many were tasked

with assisting in the civil administration. Although under the direction of the

Indian Civil Service (ICS), there were too few to run a normal bureaucracy, so

there was a dependence on individual political officers, either ICS men or army

officers, to act as governors, protected by small contingents of British and

Indian troops. Naturally, this penny-packeting of military power, while

offering a physical presence, was unsound if there was any significant unrest.

There had already been trouble. The Kurds had resisted British administration

in 1919, while concerns that the Turks

might try to retake Mosul meant that garrisons in the north were ordered

not to relinquish territory and had to remain spread out. The result was that

Lieutenant General Aylmer Haldane, who took command in March 1920, inherited a

force that was largely ‘fixed’ and that would find abandoning any part of the

country difficult, lest it is interpreted as weakness.7

1. Timothy J. Paris,

Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule 1920–1925 (London: Frank Cass, 2003),

70–71.

2. Timothy J. Paris,

Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule: The Sherifian

Solution, 2003, 72.

3. No documentation

of the roster of those present at the critical vote of March 7 survives. This

estimate is based on analysis of the photos of deputies assembled at the moment

of independence and published in the official commemoration of Independence Day:

Sa’id Tali’, ed., Dhikra Istiqlal Suriya (Cairo: Matba’at

Ibrahim wa Yusuf Berladi,

1920).

4. Phillip Knightley,

The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia, 1969, p. 124.

5. The full archive

of the King-Crane Commission can be found at

http://www2.oberlin.edu/library/digital/king-crane/ ; Andrew Patrick, America’s

Forgotten Middle East Initiative: The King-Crane Commission of 1919 (London: I.

B. Tauris, 2015).

6. Ed. David Garnett,

The Letters of T. E. Lawrence, 1939, Letters, no. 115, Memorandum to the

Foreign Office, 15 September 1919, p. 289.

7. Garnett, Letters,

pp. 285–8; Knightly and Simpson, The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia, p.

129.

For updates click homepage here