By Eric Vandebroeck

and co-workers

As reported on 9 May, the UN's special rapporteur on

human rights in Myanmar has warned of "mass deaths" from starvation and

disease in the wake of fighting between rebel groups and junta forces in the

east of the coup-stricken country.

AFP images from Kayah

state have shown villagers

manufacturing guns in makeshift factories as local defense groups go up

against Myanmar's battle-hardened military.

The independent

rights expert, who reports to the Human Rights Council, emphasized

that the lives of many thousands of men, women, and children were under threat

from indiscriminate attacks, on a scale not seen since the 1 February coup,

“that likely amount to mass atrocity crimes.”

Back in December

2012 and then again in 2015, during my personal

visit, I already reported about the problems in Kayah (earlier

called Kachin) state and its relationship with important energy

projects.

As was reported

recently that there is fierce fighting in Demoso,

Loikaw, and Hpruso townships. The regime has carried

out airstrikes on civilian resistance fighters and used artillery on civilian

areas. It has also brought

hundreds of reinforcements into Kayah State.

About 10 junta

soldiers were reportedly killed and 10 wounded during a shootout with civilian

resistance fighters in Kani Township, Sagaing Region,

on Wednesday afternoon. The Kani’s People Defense Force ambushed five military vehicles

carrying around 70 troops on the Monywa-Kalewa

highway, according to residents.

When (posted

on 5 April 2021) we asked does

Myanmar now face civil war, it looks now that Myanmar is at a point of

no return. The army’s February coup, meant to shift power within the existing

constitutional framework surgically, has instead unleashed revolutionary energy

that will be nearly impossible to contain.

Over the past four

months, protests and strikes have continued despite the reported

killing of more than 800 people and the arrest of nearly 5,000 more. On April

1, elected members of parliament from Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for

Democracy (NLD), together with leaders from other political parties and

organizations, declared a “national

unity government” to challenge the authority of the recently established

military junta. And through April and May, as fighting flared between the

junta and ethnic minority armies, a new generation of pro-democracy fighters

attacked military positions and administrative offices across the country.

However, the Rakhine

communities say that Myanmar’s National Unity Government’s (NUG)

policy on Rohingya does not represent the Rakhine people.

The NUG, formed by

elected lawmakers in mid-April to rival the military regime, on June 3 said it

would replace the 1982 Citizenship Law with legislation offering the Muslim

community citizenship and scrap the National Verification Cards that identify

the Rohingya as foreigners. The Muslims in Rakhine State identify as

Rohingya but are labeled ‘Bengali’ by many to imply they are illegal immigrants

from neighboring Bangladesh. They are denied citizenship and freedom of

movement by the authorities.

The All Arakanese

Solidarity Committee (AASC), a Rakhine State-based network of civil society

organizations, community leaders and politicians, and the Arakan Liberation

Party (ALP), has released statements in opposition NUG’s Rohingya policy.

The junta could

partially consolidate its rule over the coming year, but that would not lead to

stability. Myanmar’s pressing economic and social challenges are too complex,

and the depth of animosity toward the military too great for an isolated and

anachronistic institution to manage. At the same time, the revolutionaries will

not be able to deal a knockout blow anytime soon.

As the stalemate

continues, the economy will crumble, extreme poverty will skyrocket, the

healthcare system will collapse, and armed violence will intensify, sending

waves of refugees into neighboring China, India, and Thailand. Myanmar will

become a failed state, and new forces will appear to take advantage of that

failure: to grow the country’s multi-billion-dollar-a-year methamphetamine

business, to cut down the forests that are home to some of the world’s most

precious zones of biodiversity, and to expand wildlife-trafficking networks,

including the very ones possibly responsible for the start of the COVID-19

pandemic in neighboring China. The pandemic itself will fester unabated.

The task now is to

shorten this period of state failure, protect the poorest and most vulnerable,

and begin building a new state and a freer, fairer, and more prosperous

society. A future peaceful Myanmar can only be based on both an entirely

different conception of its national identity, free of the ethnonationalist narratives of the past, and a transformed

political economy. The weight of history makes this the only acceptable outcome

but also a herculean task to achieve. The alternative, however, is not a

dictatorship, which can no longer achieve stability but rather an

ever-deepening state failure and the prospect of a violent, anarchic Myanmar at

the heart of Asia for decades to come.

Myanmar is a colonial creation

Myanmar is a colonial

creation. Over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the

United Kingdom conquered the coastline from Bengal to

the Malay Peninsula, the valley of the Irrawaddy

River, and then the surrounding uplands. Myanmar, then called Burma, was

forged through military occupation and governed as a racial hierarchy that is

partly carried over to the present.

Modern Burmese

politics emerged a century ago, and at its core was an ethnonationalism rooted

in the notion of a Burmese-speaking Buddhist

racial identity. After winning independence in 1948, the new Burmese state

tried to incorporate those non-Burmese peoples of the country also deemed

indigenous, such as the Karens and the Shans, but

within a Burmese racial and cultural supremacy

framework. Those peoples categorized as “aliens,” such as the more than

700,000 people from the Rohingya Muslim community

viciously expelled to Bangladesh in 2016 and 2017, have fared worse.

Myanmar’s nation-building project has failed for decades, leaving behind a

landscape of endemic armed conflict and a country that has never truly been

whole.

For example as

tensions peaked between Karen and Bamar in early 1949, Burmese

irregular forces committed a series of mass killings on the outskirts of

the then-capital that have never been officially acknowledged.

The Burmese army has

been the self-appointed guardian of this ethnonationalism. It is the only army

in the world that has been fighting nonstop

since World War II: against the British and then the Japanese, and, after

independence, against an extraordinary array of opponents, including

Washington-backed Chinese nationalist armies in the 1950s, Beijing-backed

communist forces in the 1960s, drug lords, and ethnic armed forces struggling

for self-determination, all the while taking as well as inflicting enormous

casualties. Since the 1970s, most of the fighting has been confined to the

uplands, where the army became an occupation force imposing a central rule on

ethnic minority populations. But now and then, the army would descend into the

cities of the Irrawaddy River valley to crush dissent. The ranks of the armed

forces have grown to over 300,000 personnel. In recent years, the military has acquired

new Chinese and Russian combat aircraft, drones, and rocket artillery. It

is led by an officer corps that cannot imagine a Myanmar where the military is

not ultimately in control.

For four decades

after independence, successive civilian and military governments embraced

socialism in response to colonial-era economic inequalities. The main

opposition to ruling governments was communists. During the 1960s, the military

junta combined the nationalization of major businesses with extreme isolation

from the rest of the world. But that orientation shifted in 1988, when a new

army junta seized power, rejected socialism, and began encouraging private

business, foreign trade, and foreign investment. Over the following years,

however, Western countries began to impose sanctions in solidarity with a

nascent democracy movement. At the same time, the army’s principal battlefield

enemy, the Beijing-backed communist insurgency in the northeast, collapsed,

making a trade with China possible for the first time in decades. The net

result was Burmese capitalism intimately tied to China’s giant industrial

revolution next door.

Illicit narcotics syndicates

The political economy

that emerged during the 1990s and early years of this century were the most

unequal since colonial times. Illicit narcotics syndicates

flourished, especially in areas where the junta had reached cease-fires

with local militias. Timber and mining (especially of jade) enriched a cohort

of generals, militia leaders, and business partners, who invested these profits

in real estate in the country’s biggest city, Yangon, sending housing prices

millions of dollars. By 2008, newly discovered offshore gas fields provided the

junta with over $3 billion a year, money that those with the right

connections could access at ludicrously low exchange rates. Not all army

officers accumulated much wealth, but all enjoyed access to patronage networks

to transform power into wealth.

No one paid taxes,

and the state provided next to no social services, with the World Health

Organization listing Myanmar’s health system at the absolute bottom of its

table of national health systems in 2000. The army confiscated land on an

enormous scale from ordinary people. Then, in 2008, a cyclone killed

140,000 people. Landlessness, the cyclone, and other environmental threats

relating to climate change fueled an epic migration from west to east, from

lowland ethnic Burmese areas to Yangon and upland minority areas, and from

everywhere around the country to Thailand, where three million to four million

unskilled laborers from Myanmar work today. Myanmar’s ethnic demographics

became further jumbled, separating identity from a place.

Ethnonationalism had

no ideological rivals. In 1989, the generals changed the name of Burma, a

geographic term used by Europeans since the sixteenth century to mean the area

around the Irrawaddy valley, to Myanmar, an ethnonym for the Burmese-speaking

majority. Socialism and communism had been discredited. In their place came a

nationalist narrative rooted in a country's conception as a union of indigenous

“national races,” with the Burmese-speaking Buddhist people, the Myanmar

people, and their culture at the unquestioned center.

A decade ago, reforms

came about not because of sanctions or diplomatic engagement but because the

country’s aging autocrat, General Than Shwe, believed that a new constitutional

setup would help ensure him a safe and comfortable retirement. He didn’t want

to hand power to a new military dictator, who might one day turn against him,

and he believed the more prudent option was to split power between an army

under a younger cohort of generals and a government led by the pro-army party

he had created, the Union Solidarity and Development Party. But in 2011, the

reformist ex-generals leading the USDP went off script,

releasing political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi, ending media

censorship, freeing the Internet, and ushering in a level of political freedom

unknown for half a century. Western governments, hoping democracy might be just

around the corner, rolled back sanctions, and the country’s economy

boomed. The opening of the telecommunications sector sparked a revolution in

connectivity: in 2011, almost no one in Myanmar had a phone; by 2016, most

people had smartphones and were on Facebook.

The army, however,

was left in its own universe. When Than Shwe retired, he promoted a relatively

junior officer, Min Aung Hlaing, to be the new commander in chief, with the

explicit task of safeguarding the army’s preeminence. But Min Aung Hlaing and

the new crop of generals below him were decades younger than the men of the old

junta, and they had little access to the moneymaking networks of prior decades.

At the same time, the reforms begun in 2011 shrank the army’s role in the

economy considerably. It lost its privileged access to foreign currency and

corporate monopolies. Its share of the national budget was reduced. Moreover,

the army no longer had a say in economic policy. Some of its former business

partners lost out to newly arrived foreign competition; others thrived in the

open environment. But few companies were any longer dependent on the military’s

largess.

The generals wanted to upgrade their weaponry

In the 2010s, the

army placed less emphasis on moneymaking and more on the exercise of violence.

The generals wanted to upgrade their weaponry and become, in their own words, a

“standard modern army.” They dreamed of ending the country’s endless internal

armed conflicts on their own terms, using a mix of pressure and persuasion to

disarm and demobilize the many and varied forces fighting on behalf of ethnic

minority communities. Over the past ten years, their focus has been campaigning

against new ethnic minority forces, particularly the Arakan, Kokang, and Ta’ang armies, all linked to China and the ethnic cleansing

of the Rohingya. To some extent, their uncompromising stance found support

among the public, as Burmese ethnonationalism flourished on social media and

among Buddhist organizations that saw Islam and all things foreign as threats

to the conservative order they espoused.

From 2011 to 2015,

the army shared power with the reformist ex-generals of the USDP in what was

more or less an amicable relationship. But in 2016, after Aung San Suu Kyi’s

NLD won a landslide election victory, they found themselves in government with

their longtime political foes. Under the constitution, the army held three

ministries, Defense, Home Affairs (which controlled the police), and Border

Affairs, and a quarter of the seats in parliament. But Aung San Suu Kyi enjoyed

real power. Her supermajority meant she could pass any law she wished and

control the country’s budget and the entire range of government policy apart

from the security issues directly under the military’s purview.

Aung San Suu Kyi’ and the generals shared

conservative values

She and the generals

shared conservative values, including respect for age, self-discipline, and the

Buddhist establishment, and had a similar ethnonationalism worldview. They were

united in believing that the Western reaction to the Rohingya expulsions was

unfair. In 2019, Aung San Suu Kyi acted out of conviction, not expediency, when

she went to The Hague to defend the army before the International Court of

Justice. But her relationship with the generals was testy at best. The NLD

feared a coup. The army feared a conspiracy between Aung San Suu Kyi and the

West to remove it from the government altogether. Min Aung Hlaing worried that

Aung San Suu Kyi might one day throw him under the bus to placate her erstwhile

international supporters, many of whom had disavowed

her after the violent displacement of the Rohingya.

The tipping point

As political tensions

grew, the country’s economy reached a tipping point. In 2016, the central bank,

following advice from the International Monetary Fund, introduced new

prudential regulations for Myanmar’s private banks at a time when as many as

half of all loans in the country were nonperforming, and the once white-hot

real estate market had just nose-dived. Aung San Suu Kyi suddenly found that

she had leverage over a business class that many of her supporters loathed. The

cronies who had become rich under the old junta now vied for her attention. Her

technocrats pushed for further liberalization. At the same time, Beijing, which

had nurtured close ties with Aung San Suu Kyi, proposed multibillion-dollar

infrastructure projects through its Belt and Road Initiative, including the

China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, which would stretch from China’s southwestern

province of Yunnan to the Bay of Bengal.

The COVID-19 pandemic

Then came the

COVID-19 pandemic. Its impact on public health was minimal, but lockdowns and

disruptions to foreign trade sent the economy into a tailspin. The government’s

response was anemic at best, offering virtually no cash support to those

hardest hit. According to one survey conducted in October 2020, the proportion

of the population living in poverty (those making less than $1.90 a day) had

risen from 16 percent to 63 percent over the previous eight months, with a

third of people polled reporting no income since August 2020. However, public

trust in Aung San Suu Kyi only grew as she appeared on Facebook for the first

time, live-streaming conversations with healthcare workers and others. Millions

didn’t blame her for the economy’s ills and instead felt that they finally had

a leader looking out for them.

But alarm bells were

already ringing, especially outside the Burmese-majority heartland. After the

ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya Muslims, an entirely new dynamic emerged in

Rakhine State, in the west of the country: the rise of the Arakan Army, set on

achieving self-determination for the state’s Rakhine-speaking Buddhist

community. In 2018, the Arakan Army began large-scale attacks on government

positions. It was the most significant armed insurrection in Myanmar in a

generation. By late 2020, it had pinned down several army divisions and had

gained de facto authority over vast swaths of the Rakhine countryside.

At the other end of

the country, the methamphetamine industry, which supplied markets as far afield

as Japan and New Zealand, was thriving as never before. The drugs were produced

in areas controlled by militias near the Chinese border, with the bulk of profits

going not to anyone in Myanmar but too powerful transnational syndicates, such

as the one headed by the Chinese Canadian Tse Chi Lop, who was arrested in

January in Amsterdam and is purported to have made as much as $17

billion in revenue annually. Drugs encouraged a growing ecosystem of money

laundering and other illicit industries, with over a hundred casinos in the

northeast, near the Chinese province of Yunnan, and plans for a giant gambling

and cryptocurrency hub on the border with Thailand.

National elections

took place last November in the feverish context of rising conflict and

economic woes. But people still voted overwhelmingly for Aung San Suu Kyi. The

army leadership was shocked, having believed that the NLD would fare poorly,

given the state of the economy, and that the military top brass would have at

least a say in choosing the next president. Instead, Aung San Suu Kyi, thanks

to the scale of her win, seemed set to be more powerful still. Efforts by Aung

San Suu Kyi and Min Aung Hlaing to reach an understanding went nowhere. He

fixated on allegations of electoral fraud and demanded an investigation into

the election. She refused to consider this. The army felt humiliated. But

ordinary people, thrilled by her victory, could only imagine better times

ahead.

The army seized power

On February 1, the

army seized power, arresting Aung San Suu Kyi and other NLD leaders. It was billed

not as a coup d’état but as a state of emergency under the constitution. The

new junta is composed of several political parties (other than the NLD) and top

generals. Min Aung Hlaing stacked his cabinet with senior technocrats and, in

his first public appearances, promised to prioritize the post-pandemic economic

recovery and even suggested a multibillion-dollar stimulus package. He seems to

have thought that he could take over without much of a fuss, sideline the NLD,

focus on fixing the economy, and then hold fresh elections skewed to his

advantage. If so, he completely misread the public mood.

The reaction to the

coup was spontaneous and visceral. Within days, hundreds of thousands of people

poured onto the streets demanding an end to military rule, the release of Aung

San Suu Kyi and other civilian leaders, and the restoration of the elected government.

At the same time, a civil disobedience movement began, with medics leaving

government hospitals and quickly spread across the public sector, from

ministerial departments down to local administrative bodies. On February 22, a

general strike shut down businesses, including banks, all around the country.

And a campaign on Facebook meted out “social punishment” in the form of

orchestrated public attacks on any person or business thought to have links to

the army or the junta.

The army cracked down

mercilessly. It had held back at first, perhaps in the hope that the protests

would melt away on their own. But over the last week of February,

battle-hardened troops of the army’s elite light infantry divisions, including

the units responsible for the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, began moving

into Yangon and other cities. A campaign of terror accompanied the lethal use

of force: as night fell, the Internet went dark, and soldiers began firing

indiscriminately in residential neighborhoods, setting off sound grenades,

breaking down doors, and hauling people away. The large crowds dissipated, but

smaller and even more determined protests persisted. Young men and women

erected makeshift barricades and wielded shields and occasionally improvised

weapons to defend themselves against the soldiers’ automatic fire. On March 14

alone, dozens were killed in Yangon’s industrial suburb of Hlaingthaya.

On March 27, over a hundred died as the army opened fire on crowds across

Myanmar.

The carnage

radicalized the resistance. With videos of the beating and killing of civilians

shared over the Internet, the popular desire to reverse the coup transformed

into a determination in some quarters to see an end to the army altogether.

Protesters raised signs calling for “R2P,” referring to the principle of “the

responsibility to protect,” which obliges the international community to

intervene in a country to defend its people from crimes against humanity, even

if such action violates that country’s national sovereignty. For a while, many

in Myanmar genuinely expected that the world would save them from a new

dictatorship. But by late March, with no armed international intervention in

sight, many young protesters turned to armed insurrection. In Kalay, near

India, residents resolved to fight back as the “Kalay Civil Army,” arming

themselves with homemade hunting rifles, killing several soldiers, and

holding out for ten days before the army overran their positions. Dozens of new

groups, locally organized and lightly armed, began appearing in different parts

of the country over the following months. In May, another militia called the Chinland Defense Force held the town of Mindat,

in the rugged western uplands, for three weeks before the army, using artillery

and helicopter gunships, forced them to withdraw. All the while, hundreds of

young men and women made their way to territories controlled by ethnic minority

armies to receive training, including in explosives. By late May, there had

been dozens of arson and other attacks on police and administrative offices and

nearly a hundred small bombings against junta-linked targets, including in

Yangon.

These new guerilla

movements can certainly keep the junta off balance. But the insurrectionists

will not build a new army to challenge the existing one without significant

help from a neighboring country, which seems next to impossible. And nothing in

the history of Myanmar’s army suggests that a sizable chunk of its forces

would break away and join a rebellion. That leaves the ethnic minority armies

as the only other possible agents of a broader uprising. The Kachin Independence Army and the Karen National Liberation Army have already mounted

new army positions in the far north and southeast of the country. Other groups,

too, may move from statements of political support to armed action. But even

the combined might of the ethnic armed organizations, numbering perhaps 75,000

fighters in total, would be no match for military with far superior artillery

and a monopoly on airpower. Moreover, the most powerful ethnic armed

organization, the United

Wa State Army, with 30,000 troops, has deep links

to China, having emerged from the old communist insurgency. It will heed the

advice of Beijing, which has no love for the Myanmar army but does not want to

see an all-out civil war.

The United Wa State Army (UWSA) is a non-state armed group that

administers an autonomous zone in the difficult-to-reach Wa

Hills of eastern Myanmar. As China expands its geopolitical interests across

Asia through the Belt and Road Initiative, the Wa has

come to play a pivotal role in Beijing's efforts to extend its influence in

Myanmar:

More than anything

that happens on the battlefield, it is the ongoing implosion of the economy

that will turn Myanmar into a failed state. Industries on which ordinary

households rely, such as tourism, have collapsed, as have other sources of

income, such as remittances from overseas, which totaled as much as $2.4

billion in 2019, a result of income lost by migrant workers abroad during

the global pandemic. The garment industry employed over a million people, many

young women, and was a success story during the past decade. Still, it has been

devastated as orders from Europe have dried up. The future of the agricultural

sector, the biggest employer in the country, remains uncertain, with logistics

disrupted by strikes and China now closing border crossings out of fear of

COVID-19. The most critical is that the financial sector has been paralyzed by

a mix of strikes, the unwillingness or inability of the central bank to provide

added liquidity, and a general collapse in confidence. Closed banks mean no cash

at ATMs and thousands of businesses unable to make payroll, taking trillions of

kyats (equal to billions of dollars) each month out of circulation. The

knock-on effect across all sectors has been catastrophic.

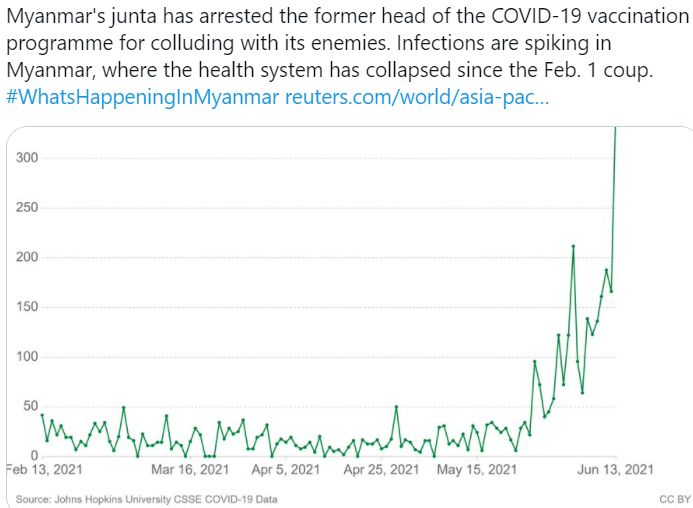

As for the current

state of Covid, Local media reports Myanmar military gov has been preparing a

quarantine center in Yangon as the COVID-19 outbreak hits the country, see

picture. The regime forcibly shut down Q centers with full medical facilities

by the civilian gov right after the coup.

The economy may be on

its knees, but the junta will likely not suffer. Revenues from natural gas and

mining will continue to flow into its coffers. The army-owned conglomerates

provide at most a fraction of the $2.5 billion, or so the military receives annually

from the regular budget. So foreign sanctions on those firms won’t have much

effect. In any case, the junta now controls the country’s entire $25

billion budget: the first cuts won’t be to defense in any fiscal squeeze.

But the people of

Myanmar will suffer enormously. The UN Development Program expects half of

Myanmar’s population of 55 million to fall into poverty over the coming six

months. The World Food Program worries that 3.5 million more people will face

hunger. Lifesaving medicines and treatments are in extremely short supply. Over

the course of 2021, 950,000 infants will not receive the vaccines that they

would normally get for diseases such as tuberculosis and polio. Those who

suffer most will include those who have always been the most vulnerable,

including landless villagers, upland farmers, migrant workers, the Rohingya,

people of South Asian descent, and the internally displaced. The economy will

collapse not with a bang but with a whimper as a new generation grows up

severely malnourished and uneducated.

Myanmar as a failed

state may look something like this: The army holds the cities and the Irrawaddy

valley, but urban guerilla attacks and a spreading insurrection prevent any

firm consolidation of junta rule. The strike's end, but millions remain unemployed,

and the vast majority of people have little or no access to basic services.

Some ethnic armed groups can carve out additional territory, while others come

under withering air and land assault. In Rakhine State, the Arakan Army expands

its de facto administration, and in the eastern uplands, old and new militia

groups strengthen their ties to transnational organized crime networks.

Extractive and illicit industries become a bigger piece of Myanmar’s economic

pie. As armed fighting intensifies, Beijing, fearing instability above all,

feels compelled to increase its sway over all territories east of the Salween

River. Myanmar becomes a center for the spread of disease, criminality, and

environmental destruction, with human rights atrocities continuing unchecked.

Successful change must come from within

Myanmar’s future need

not be totally bleak, however. Successful change must come from within, and

there is absolutely no doubt, given what has happened since February, that

Myanmar’s young people are determined to alter the course of their country’s

history. It is they who must chart a path forward. But global action now could

alleviate some of the sufferings in the country and help it more swiftly escape

impending disaster.

First, the

international community needs to agree to a resolution in the UN Security

Council that clearly demands a quick and peaceful transition back to an elected

civilian government. China must be on board; there is simply no substitute for

China’s involvement because of its economic clout in Myanmar and its deep ties

to many of its ethnic armed organizations. International sanctions that do not

involve China may be symbolically important, but they will be just that:

symbolic. The junta can survive with just China’s tacit support. But Beijing

can play a constructive role. It has always had difficult relations with the

generals, is wary of instability, would prefer a return to civilian government,

and remains uncertain of its next moves. Diplomacy between Beijing and

Washington will be essential in achieving a Security Council resolution and

thereby providing the needed framework for international cooperation on

Myanmar. Several countries in the region are important, especially India and

Thailand, Myanmar’s other key neighbors, and Japan, whose aid and investments

have been a big part of the country’s economic growth over the past decade. The

Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the regional body, is far less

significant; it initiated dialogue with the junta in April that has yet to bear

fruit.

Second, outside

powers must support and encourage all those working not only for democracy in

Myanmar but also for the broad transformation of Myanmar politics and society.

That includes serious efforts, possibly through an expanded UN civilian

presence in Myanmar, to monitor human rights abuses and negotiate the release

of political prisoners. However, it is critical not to raise false hopes by

offering people in Myanmar the chimera of international salvation; that would

only steer energy away from building the necessary and broadest possible

coalitions at home.

Third, outside help

needs to be based on an appreciation of Myanmar’s unique history, one in which

past army regimes have withstood the strictest international isolation and the

unique psychology of the generals themselves, molded by decades of unrelenting

violence. The international community’s usual carrots and sticks won’t work.

Fourth, foreign

governments should assist poor and vulnerable populations as much as possible,

perhaps focusing initially on providing COVID-19 vaccinations. But such

assistance must be handled with tremendous political skill and designed in

collaboration with healthcare workers themselves, not inadvertently to entrench

the junta's grip. Many of the junta’s opponents have wanted to crash the

economy to help trigger revolution. Still, as weeks stretch into months and

years, it will be necessary to protect the civilian economy as much as

possible, to prevent a worsening humanitarian disaster. Responsible global

firms that do not do business with the army should be encouraged to stay in the

country. A healthy and well-fed population will be better able to push for

political change.

Governments must try

different initiatives with as much flexibility and international coordination

as possible. There is no magic bullet, no single set of policies that will

solve the crisis in Myanmar. That’s because the crisis isn’t just the result of

the February coup; it is the outcome of decades of failed state-building and

nation-building and an economy and a society that has been so unjust for so

long to so many. The outside world has long tended to see Myanmar as a fairy

tale, shorn of its complexities, in which an agreeable ending is just around

the corner. The fairy tale must now end and be replaced with serious diplomacy

and well-informed, practical strategies.

Conclusion

The Tatmadaw is far

from being defeated. Even if its opponents band together, as the shadow

government hopes, its 350,000-odd soldiers would still dwarf the rebels’

combined forces of around 80,000. Over the past decade, it has built up an

arsenal of sophisticated weaponry, enabling it to mount combined land and air

offensives. A resolution passed on June 18th by the UN General Assembly,

calling for an end to arms sales to Myanmar and an end to violence and the

release of detainees will make little difference. The Tatmadaw’s two

biggest suppliers, China and Russia, abstained.

There have been hundreds

of defections from the army since the coup, but it is doubtful that enough

would abandon the force to influence the conflict’s outcome. Plus, their

fortunes may change with the weather. Hostilities with ethnic rebels, who live

in the country’s uplands, are usually suspended when the monsoon arrives. If

that annual pattern holds this year, the Tatmadaw may redeploy troops to the

heartland.

The shadow

administration, known as the National Unity Government (NUG), is trying to knit

the disparate anti-regime forces into a standing army. But different ethnic

rebels are wary of one another, past efforts at co-operation have failed, and

of the NUG, which a Bamar political party formed criticized before the coup for

ignoring the grievances of ethnic minorities. Even the Chin National Front, the

only ethnic militia formally allied with the NUG is worried that Bamars will dominate their coalition, says Salai Lian Hmung

Sakhong, the front’s vice-chairman and the NUG’s

minister of federal affairs. Some rebel groups have no interest in taking on

the Tatmadaw. They include the biggest, the United Wa

State Army, with 30,000 troops. Others, such as the Arakan Army, which had

engaged the Tatmadaw in fierce fighting until last November, saw an opportunity

to extract concessions from the army while under pressure.

But the fragmented

nature of the resistance also makes it more difficult for the Tatmadaw to root

out insurgents. The Tatmadaw’s brutality has turned the entire country against

it. For the first time since some students took up arms after the bloody suppression

of an uprising in 1988, Bamars joined ethnic rebels

in their war against the army.

For updates click homepage here