It was not long ago

that Aung San Suu Kyi came to the Hague to defend Myanmar to rebuff charges that Myanmar carried out a systematic

campaign of mass murder, rape and terror against the Rohingya.

Here fiery speach where she claimed the Rohingya were in fact the

guilty party which did

little to convince the UN Security Council which referred the matter

to the International Criminal Court, in order to establish an ad-hoc tribunal

on Myanmar or having countries with universal jurisdiction use it to deal with

the plight of the Rohingya Muslims who fled

military crackdowns to Bangladesh.

During a 17 Sept.

news conference in the Palais des Nations a UN panel stated that Myanmar incurs

state responsibility under the prohibition against genocide and crimes against

humanity, as well as for other violations of international human rights law and

international humanitarian law. And that Myanmar’s civilian leader, Daw

Aung San Suu Kyi, could face prosecution for crimes against humanity committed

by the military.

Whereby now Suu

Kyi herself became

the victim of the military she once so violently defended.

Given the current

situation however the U.N. special envoy for Myanmar now warns that the country

faces the possibility of civil war at

an unprecedented scale.

Does Myanmar now face civil war?

On Friday, most

Myanmar citizens woke up to no internet access.

Myanmar's military

junta has cut all

wireless internet services until

further notice, in what appears to be part of a concerted effort to control

communications and messaging in the Southeast Asian country.

Rights group Human

Rights Watch (HRW) said Friday that the junta had also "forcibly

disappeared hundreds of people" -- including politicians, election officials,

journalists, activists and protesters -- since the February 1 coup.

The co-chairs of the

United Nations Group of Friends for the Protection of Journalists on

Thursday issued a

statement voicing

"deep concern over the attacks on the right to freedom of opinion and

expression and the situation of journalists and media workers in Myanmar and

strongly condemn their harassment, arbitrary arrests and detention, as well as

of human rights defenders and other members of civil society."

Myanmar’s rulers this week crossed a threshold few governments

breach anymore: They have killed, by most estimates, more than 500 unarmed citizens of

their own country.

Such massacres by

government forces have, even in a time of rising nationalism and

authoritarianism, been declining worldwide. This is the seventh in the past

decade, compared with 23 in the 1990s, according to data from Uppsala University in Sweden.

And the violence in

Myanmar was carried out by a sort of government that has grown rarer still:

outright military rule.

Myanmar does not

signify a return to an earlier era, experts believe, so much as an echo. Its

violence hints at the ways in which the world has changed, and hasn’t.

Governments are more

oppressive but, with a handful of exceptions like Syria, less likely to kill

their own people at scale. Dictatorships are more common but less overt. And

world powers have come to shun the government crackdowns they once encouraged.

Myanmar is unusual

partly because it is a country out of time, resembling a bygone style of

autocracy, but also for the ways in which it is unique.

And those traits,

experts say, helped enable the February coup led by Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, and the subsequent

crackdown on peaceful protesters. They also point to a long and difficult road

ahead.

No two crackdowns are

alike, each brought about by events and personalities particular to its time

and place. But scholars have identified a set of factors that make a government

likelier to kill large numbers of its own citizens. And virtually all are present

in Myanmar.

Perhaps the most

important warning sign: direct military rule.

Military rulers tend

to be more aggressive in deploying troops to crush dissent. And unlike civilian

autocrats, they have little reason to fear the troops turning on them, as

happened when Romania’s armed forces ousted the communist rulers who’d ordered them

to open fire on protesters in 1989.

Most primes military

rulers get paranoid and don’t have a sense for what levels of dissent are

acceptable in society, so they might be quicker to use force against their

citizens, such rulers usually tend to have a kneejerk reactions to threats.

Myanmar’s generals

are typical in this sense: experienced at fighting, politically powerful, but

unfamiliar with the give-and-take required of even autocratic rule. Force is

the tool they know best.

The country bears

another serious risk factor: its civil war, raging against various ethnic

militias since the 1940s.

Most militaries see

themselves as protectors against foreign threats, with a strong taboo against

committing violence at home.

But civil war can

break that taboo, normalizing the idea that deploying domestically is

legitimate, and making it easier to see fellow citizens as enemies.

And it accustoms

generals to the idea that their proper place is not guarding the borders but imposing

order at home. Myanmar’s military has considered this its role for decades —

even when it allowed elections and limited civilian government in the years

before the coup, it granted itself permanent seats in the legislature.

Few factors predict

future government massacres like past ones. And it has been less than four

years since Myanmar’s conducted one of the bloodiest of the 21st century,

targeting thousands of members of the country’s Rohingya minority in what the

United Nations and human rights groups called a

genocidal campaign.

International

outrage, though severe, did little to the leaders’ calculus. And much of the

domestic response to the Rohingya killings was supportive. Social media filled

with praise for the campaign and the military officers who led it.

The current violence

is not surprising “because of the genocide and the fact that they were able to

get away with it with very little repercussions,” Dr. Frantz said.

Once a military kills

its own with impunity, and even feels it benefited from the bloodshed, there is

very little to stop it from doing so again.

Country missed out on a change how dictatorship works

The era of armed

forces rule peaked between 1960 and 1990, when dozens of countries around the

world came under full or partial military dictatorships, many of them propped

up by the United States or the Soviet Union.

When the Cold War

ended, that number collapsed to just a handful, and has been steadily declining

ever since, according to data maintained by One Earth Future, a research

foundation.

Government-sponsored

massacres became less frequent too. But a wave in the 1990s were mostly in

countries that, like Myanmar, had histories of civil war, weak institutions,

high poverty rates and politically powerful militaries, Sudan, Rwanda, Nigeria,

Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, among others.

Though they largely

failing to stop those killings as they happened, world leaders and institutions

like the United Nations built systems to encourage democracy and avert future

atrocities.

Myanmar, a pariah

state that had sealed itself off from the world until reopening in 2011, didn’t

much benefit from those efforts.

The country also

missed out on a global change in how dictatorship works.

A growing number of

countries have shifted toward systems where a strongman rises democratically but

then consolidates power. These countries still hold elections and call

themselves democracies, but heavily restrict freedoms and political rivals.

Think Russia, Turkey or Venezuela.

Repression in the

last couple of years has actually gotten worse in dictatorships. But

large-scale crackdowns are rarer, in part because today’s dictators are getting

savvier in how they oppress.

Only 20 years ago, 70

percent of protest movements demanding democracy or systemic change succeeded.

But that number has since plummeted to a historic low of 30 percent, according

to a study by Dr. Erica Chenoweth of Harvard University.

Much of the change,

Chenoweth wrote, came through something called “authoritarian learning.”

New-style dictators

were wary of calling in the military, which might turn against them. And mass

violence would shatter their democratic pretensions. So they developed

practices to frustrate or fracture citizen movements: jailing protest leaders,

stirring up nationalism, flooding social media with disinformation.

Some Myanmar

experts argue that the country’s civilian leader, Daw Aung San

Suu Kyi, was pulling the government in this direction before the

generals seized power for themselves.

But there is one way,

experts stress, in which the world has not much changed: its seeming inability

to stop government-sponsored killings once they begin.

Once the military is

involved in politics, it’s hard to get them out if they don’t want to get out.

Most military rulers

do step down after a few years, usually in response to an economic downturn,

protest movement or other headache that they decide they don’t want. And

usually with a promise that they can keep their ranks and salaries.

But there is a big

exception: Rulers who oversee atrocities tend to stay in office more or less

for life.

They usually cling on

until the end because they know there’s a lot of uncertainty should they

leave power. Rather than risk prison time or war crimes charges, they do

whatever it takes to hold power.

As to what next, the

restoration of ‘democracy’ should not be the goal of Western policies

vis-à-vis Myanmar. Instead, the goal should be restoration of some form or

semblance of civilian and constitutional rule.

Conclusion

The military regime’s

brutal killings and extreme violence against peaceful anti-regime protests

since its coup have led Myanmar to the verge of a full-blown civil war and

urban combat.

For weeks following

the coup, the approximately 20 ethnic armed groups that have fought for

autonomy for decades, but which signed ceasefire agreements with previous

governments in recent years, did nothing in regard to the nationwide

anti-regime protests. But more recently, some of them, including the KIA and

the Karen National Union (KNU), based in the eastern part of the country, have

started announcing that they stand with the people against the military

dictatorship.

On March 27, Brigade

5 of the KNU’s military wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), seized

a hilltop outpost held by the military regime in Karen State. The KNLA killed

10 soldiers including an officer and arrested eight soldiers as prisoners of

war.

In retaliation,

within a few hours the regime launched airstrikes against the KNLA using two

fighter jets in Papun District, Karen State. More

than a dozen Karen people were killed and thousands of people fled their

villages in the wake of subsequent airstrikes.

In northern Kachin

State, the KIA launched offensives against a military outpost in the

jade-mining hub of Hpakant and another military outpost in Injangyang

Township on March 15, days after the regime’s troops killed at least three

young protesters in Myitkyina, the state capital. In the following days, the

KIA launched more offensives and clashes continued between the KIA and the

regime’s troops.

The KNU is among 10

ethnic armed groups that signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) with

the previous government, as well as the military itself. But the regime’s

brutal killings have forced it officially to break the agreement. More clashes

between the KIA and the KNU and the military are highly likely in Karen and

Kachin states. And police stations and military outposts in the towns and

cities in those areas are likely to continue to be targeted in the coming days,

weeks and months.

And that’s not all.

In late March, the

Brotherhood Alliance of three armed groups warned the military that it would

collaborate with other ethnic armed organizations and pro-democracy supporters

to defend the people from the regime’s brutal crackdowns if the violence continued.

The Arakan Army (AA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) and

Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) issued their

condemnation of the regime amid daily increases in the civilian death toll.

These armed groups

are active in their territories in western Rakhine State and in northern Shan

State. Unlike the KNU, they have not signed the NCA.

The anti-military

dictatorship movement sees no room for compromise at all. Civil war and urban

conflict, therefore, seem unavoidable. Myanmar has already suffered a more than

70-year-long civil war since independence in 1948, though the fighting has mostly

been confined to remote or border areas. But the war this time will be

different. Not only will the civil war spread inland from the borders, but

urban warfare will erupt from within our cities.

All five of the above

armed organizations have urged the coup leaders to stop their violent

crackdowns, release all civilian leaders and detainees, restore democracy and

accept the results of the 2020 general election, which the NLD won in a

landslide.

More of the 20 armed

organizations are likely to join the fight that erupted in response to the

anti-coup movement in the cities if the military regime keeps killing innocent

people and terrorizing the entire population. If that is their plan, however, they

should act soon, as the military regime pays no heed not only to its own people

but also to the international community. Over the past two months, the world

has repeatedly made the same demands as those listed above. But the coup

leaders have just ignored them, which shows they will not stop killing and

violently oppressing their own people.

And with the

anti-military dictatorship movement sees no room for compromise at all. Civil

war and urban conflict, therefore, seem unavoidable. Myanmar has already

suffered a more than 70-year-long civil war since independence in 1948, though

the fighting has mostly been confined to remote or border areas. But the war

this time will be different. Not only will the civil war spread inland from the

borders, but urban warfare will erupt from within its cities it seems.

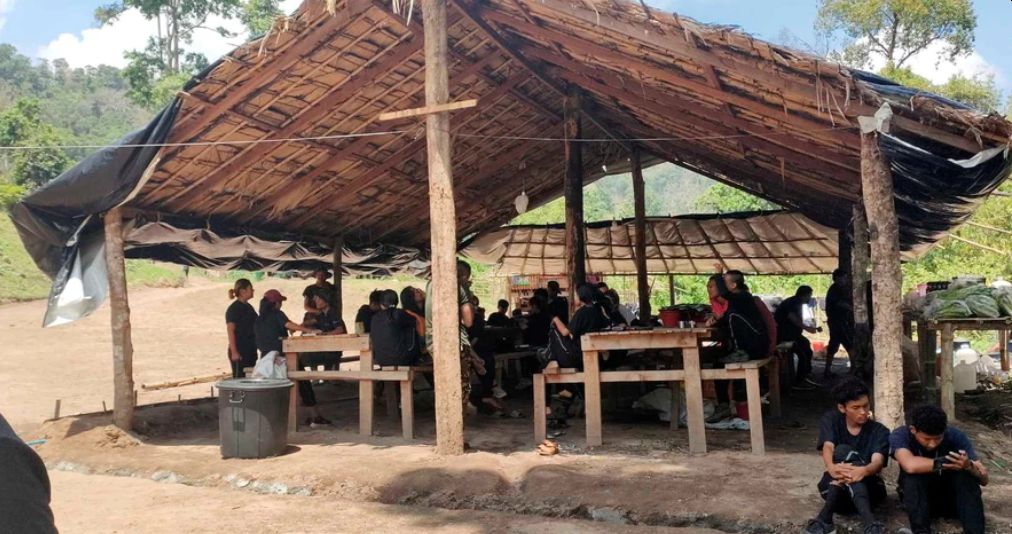

As a recent article

in Australia mentioned Aung Maunge was warned he

faced life imprisonment if he rejoined demonstrations. That has only

strengthened his conviction that peaceful protest alone cannot dislodge the

junta. He is now headed north to Kachin State,

where rebel forces are training young protesters in armed resistance.

“The military will do

anything, kill anyone, to stay in power,” he said. “We

have to combine this social movement with armed struggle. I know a lot of

other people also going to Kachin and Kayin State, because we have no choice.

Also, one of the

oldest and largest ethnic armed groups, the Karen National Union (KNU), said

that protesters coming from the lowlands of central Myanmar have been trekking

to the rebels’ hilly jungle holdouts for training since late March. “We train

people who want to be trained and who want to fight against the military

regime,” said Maj. Gen. Nerdah Bo Mya, chief of staff

of the Karen National Defense Organization, an armed wing of the KNU. “We are

[on] the same boat, helping one another. [We] help each other to survive and

get rid of the military regime and to re-establish what we call the democratic

government,” he said.

The general said

ethnic Karenni, Rakhine, and Shan rebel groups were

doing the same.

For updates click homepage here