By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

From the standpoint

of thirty- five years of Sino-Iranian cooperation, the specific strategic content

of that cooperation in specific periods is secondary. During the 1970s

Sino-Iranian cooperation was directed primarily toward containing Soviet

Indian- Iraqi "expansionism." During the 1980s its primary content

focused on the conduct and international politics of the Iran-Iraq war. During

the 1990s the substance of Sino-Iranian cooperation shifted to an oil

for-capital-goods swap and countering u. s. "unipolarity" in an

"unbalanced" post -Soviet world. Taking an even longer view, in

ancient times Sino-Persian cooperation was directed against the Xiongnu. During the early medieval period it was directed

against the Arabs. In the future it may well be directed against some other

power. The specific opponent and content are transitory. It is the element of

cooperation between China and Persia that endures and is fundamental. To say it

another way, the Sino-Iranian relation is essentially about power and influence.The Sino-Iranian relation partners two proud

peoples who see in the other an affirmation of their own self-identity. They

respect the history of the other and are aware of the long chronicle of

mutually beneficial contact and, sometimes, cooperation between the two

nations. They see that historic cooperation as an important element of the

world order prior to the European eruption and their consequent humiliation,

and are determined to cooperate in putting the world once again to right. They

share a large set of values about the unjust condition of the modern world.

Each respects the power, strong national consciousness, and national

accomplishments of the other and sees in it an influential partner well worth

cultivating. The ways in which China and Iran cooperate will vary depending on

mutual interests, but the impulse toward cooperation will remain constant.

In the event of a

U.S.-PRC military confrontation that became protracted and in which the United

States used its naval supremacy to blockade China 's coast, China 's ability to

continue prosecution of the war would be influenced by its ability to import

vital materials overland. In such a situation it would be extremely useful to

have robust and redundant transport links via Pakistan and Iran and to have

long-standing, cooperative ties "tested by adversity" with both of

those countries.

Iran, along with

Pakistan, plays an increasingly important role in providing western China

access to the oceanic highway of the global economy. Economic and strategic

factors converge here. The striking success of China 's post -1978 development

drive was predicated on integrating eastern China into the global economy, and

that, in turn, was predicated on the many fine ports on China 's east coast.

Those ports offered access to the oceanic highways that carried

China-manufactured goods to distant markets. Western China, locked deep in the

interior of Eurasia , suffered a distinct disadvantage in this regard. Western,

interior provinces, with strong support from Beijing, attempted to mitigate

this disadvantage by opening transport links with their neighbors. Yunnan

province in China 's southwest achieved considerable success in opening or

improving road, riverine, and rail links with and through Myanmar to ports

(including several that were China built) on the Bay of Bengal. Myanmar 's

location in the southeastern foothills of the Tibetan plateau had for many

centuries made it a natural transit route between southwestern China and the

Bay of Bengal . Xinjiang was not so fortunate. Its traditional international

trade routes were the long and tenuous lines of the various "silk

roads" across Central Asia . Beijing attempted to strengthen Xinjiang's

transport links with Central Asia.

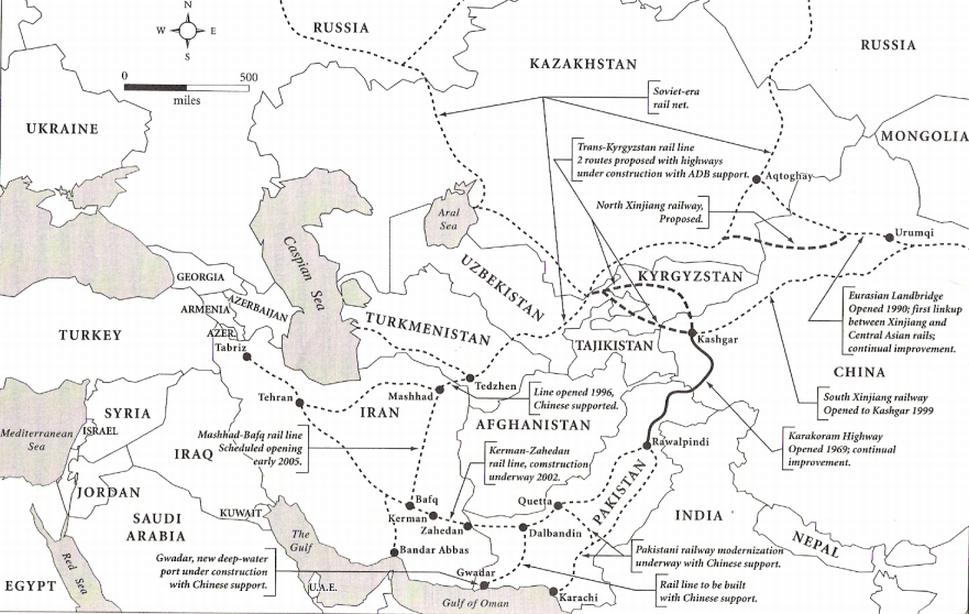

In 1990 the Soviet

Central Asia railway grid was finally linked to that of Xinjiang when a line

was opened between Urumqi and Aqtoghay, Kazakhstan.

Then in the late 1990s a rail line was pushed south along the western rim of

the Tarim Basin, reaching Kashgar

by 1999. As of 2005, construction of two trans- Kyrgyzstan highways running

westward from Kashgar is under way, with the

intention of eventually transforming one of those routes into a rail line The

China-supported construction of the rail line from Mashhad to Tedzhen, Turkmenistan, opened in 1996, as noted earlier,

was also part of this effort to link Xinjiang to Iranian ports. The map (drawing)

below shows these various transport routes.

China 's adoption in

2000 of a program to accelerate development of its western regions made

development of transportation lines to the southwest even more important.

Pakistan was China 's major partner in this regard. In August 2001 Premier Zhu Rongji committed China to provide $198 million to support

the first phase of construction of a new seaport at Gwadar in Pakistan 's

Baluchistan.(" China Assisted Gwadar Port to Be Completed in Three

Years," Karachi Business Recorder, September 16, 2002 ).

Zhu also promised

unspecified support for two subsequent phases of the project. When complete,

the new Gwadar port was to have a cargo throughput capacity equivalent to

Karachi , thereby nearly doubling Pakistan 's maritime capacity and allowing

cargoes to circumvent Karachi 's extremely crowded facilities. Also in 2001,

China committed $250 million to assist Pakistan in modernizing its railway

system.(Nadeem Malik, " China Pledges US$1 Bn Honeypot for Pakistan ,"

Asia Times, May 15,2001)

In March 2003 Beijing

committed an additional $500 million to Pakistan 's railway modernization,

including construction of new tracks. ("Finance Advisor Speaks on Jamali's

China Visit," Nation, Islamabad, March 24, 2003).

China also agreed to

provide financial support for construction of a new rail line northward from

Gwadar and linking up at Dalbandin with the existing east-west rail line. China

also agreed to finance construction of a highway east from Gwadar along the Makran coast. Simultaneously measures were taken to

expedite the flow of truck traffic along the Karakoram Highway running from Kashgar to Rawalpindi in northern Pakistan.

While China 's major

transportation investments in southwest Asia have been in Pakistan , Iran has

played a role via several railway projects that dovetailed with China 's

efforts in Pakistan . The first of these Iranian projects was construction of a

rail line between Kerman in southeast Iran and Zahedan on the Iran- Pakistan

border. Work on this line was under way in 2002.When complete, this rail line

will link the Iranian and Pakistani rail systems for the first time. Work was

also under way on a new rail line extending southwest from Mashhad directly

across northeastern Iran to Bafq. This line was to be

operational by early 2005. The completion of these new lines will mean that

Chinese cargo moving via the Tedzhen-Mashhad link can

proceed directly to seaports without having to take the long, circuitous, and

crowded but previously required detour via Tehran . Once these new lines are

open, Chinese cargo will also be able to move between Pakistan and Iran and via

ports in either of those two countries. These new lines will add considerable

redundancy to China 's southwest Asia transportation system. ("Finance

Advisor Speaks on Jamali's China Visit," Nation (Islamabad ), March 24,

2003).

There also have

been elements of conflict as well as cooperation in the Sino- Iranian

relationship. Throughout the history of post-1971 Sino-Iranian relations there

has typically existed an asymmetry in interest in a closer partnership to

counter one or another superpower. During the pre-1979 era, it was China that

was the more ardent suitor in the SinoIranian

relationship, with Beijing pressing Tehran to playa

greater role in what Beijing saw as the emerging global united front against

Soviet social imperialist expansionism. The shah was reluctant to go down that

path. His aim in cooperating with China was deterring and moderating Soviet

behavior, not provoking the Soviet Union . China , however, felt a dire threat

of encirclement or even direct attack by the Soviet Union, and urgently wanted

a global anti-Soviet coalition that would lessen Soviet pressure on China .

During the post-1979 period, the situation was reversed. Tehran became the more

ardent suitor and Beijing the more hesitant party. Confronted with the

deterioration of relations with the United States , the European countries, and

its Arab neighbors, Iran needed friends. The end of the Iraq- Iran war freed

Moscow from its alliance obligations to Iraq and opened the door to

Soviet-Iranian cooperation, but the dissolution of the Soviet state greatly

reduced the willingness and ability of Russia to support Iran against the West.

In its search for international partners during the 1990S, Tehran propounded

joint Iranian-Chinese confrontation of the United States and various sorts of

anti-u. S. hegemony blocs to include China, Iran, India, Pakistan, Russia , and

even Japan. Beijing was not interested. Tehran responded by criticizing China's

close relations with the United States in 1979, during Reagan's 1984 visit, and

again when Beijing capitulated to U. S. pressure over nuclear and missile

cooperation in 1997. Beijing moved to mollify Iranian criticism but did not

alter the course of its underlying U. S. policy.

Beijing has been wary

of overly close association with the I R I. The potential financial costs of

close association with Iran may have been one Chinese consideration here. A

major element of antihegemony, Third World solidarity was to be, Tehran

insisted, robust Chinese financial support for development projects in Iran. A

key theme of China 's post-1978 foreign policy line was to avoid, with rare

exceptions (one of which was the Tehran metro), such costly overseas projects

that, Deng Xiaoping felt, had helped impoverish China under Mao Zedong's rule.

Iran 's very size meant that as an ally its demand on Chinese resources could

be quite heavy.

Political factors

were probably more important in explaining the distance Beijing maintained in

ties with the IRI. Overly close association with the IRI could hurt China 's

international reputation. Deng Xiaoping strove quite effectively to shed China

's revolutionary image acquired during Mao's rule. Close association with

revolutionary Iran ran counter to Deng's effort to normalize China 's

reputation and diplomacy. After 1978 and with increasing clarity into the

1990s, China desired to be accepted as a responsible power qualified to be

admitted by the international community into the ranks of the leading nations

of the world. Achievement of this respectability was not facilitated by close

association with Islamic revolutionary IRI or by implication in possible IRI

nuclear weapons efforts. Close alignment with the IRI could also injure China

's ties both with the Arab countries and with Israel.

There were also

numerous smaller frictions in the Sino-Iranian relationship. The propensity of

some Iranian foundations, and perhaps even the IRI government, to foster radical

Islamic thought in China's Muslim communities and in Central Asian countries

contiguous to China generated conflict in the P RC- IRI relation. This conflict

led not to estrangement but, paradoxically, to greater emphasis on

"friendship." Beijing sought to demonstrate to Tehran that

cooperation with China was valuable, but that such cooperation would be

impossible ifIranian "interference" in the

affairs of China 's Muslim communities continued. In effect, Beijing made

cessation of Iranian subversion the price of Chinese friendship and

cooperation. Conflict thus led to engagement and friendship, rather than to

sanctions and hostility.

Tehran sometimes

defaulted on payment of its bills to Beijing . Difficulties of doing business

in Iran certainly tested the patience of Chinese businesspeople no less than

German, South Korean, Canadian, or Norwegian. Arbitrary and unilateral Iranian

changes in agreements sometimes led to Chinese protests. So to

did Iranian "discrimination" against Chinese goods in favor of

Western technology. Negotiations over business deals were often long and hard,

with Iranian calls for Third World solidarity being met with Chinese insistence

on mutual benefit.

The U.S. invasion of

Iraq was not, on the face of it, an overtly "colonial" venture.

Judging by the Bush administration's own objectives, the invasion of Iraq in

fact was a colossal blunder, and although not geared towards imperialist

objectives in the Middle East, it was indeed relying on military force. Yet the

United States did not become the dominant power by military means. Victory in

the Second World War was followed by the establishment of the United Nations

and the Bretton Woods institutions and the Marshall Plan.

Nevertheless the

behavior of the United States was not always exemplary-the CIA was busy

hatching plots, planning assassinations, and arranging coups d'etat ; but most of these activities were clandestine, and

when they were revealed, the CIA was reined in. The Vietnam War ended in defeat

and broke the can-do spirit that had characterized America until then. The

United States continued to fight proxy wars and to sustain authoritarian

regimes. But these were aberrations.

The world order is

based on the sovereignty of states. An anachronistic concept at the time, it

first entered the vocabulary of modernity with the Treaty of Westphalia in

1648. After thirty years of religious wars, it was agreed that the ruler had

the right to determine the religion of his subjects. Next the French Revolution

overthrew King Louis XVI and the people seized sovereignty. Since then, the two

instances of partial sovereignty, have gradually transformed into the

democratic principle as recognized by the United Nations, following the end of

WWII. There has never been a world order capable of preventing war, but the

idea that there is no world order other than the use of force is a fallacy-a

companion piece to the misinterpretation of the nature of power.

After the collapse of

the Soviet empire, America under George W. Bush, used its dominant position to

promote its national self-interest. The United States , as the dominant power,

however could have chosen instead to concern itself with the well-being of

humanity in addition to pursuing its self-interest. There has been a profound

shift in American attitudes since the Marshall Plan was implemented. When the

Soviet Union collapsed, the idea of a Marshall Plan for the former Soviet

empire could not even be discussed. The emergence of a different attitude from

the one that gave birth to the Marshall Plan can best be identified as ‘market

fundamentalism’-a belief that the common interest is best served by people

pursuing their self-interest.

Furthermore,

facilitating the international movement of capital has made it difficult for

individual countries to tax or regulate capital. Since capital is an essential

factor of production, governments have to pay more attention to the

requirements of international capital than to their own citizens. Thus the

development of international institutions has not kept pace with the growth of

global financial markets. Private capital movements far outweigh the facilities

of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Developing countries are

vying to attract capital, yet the world's savings are being sucked up to

finance over consumption in the United States, and now also Europe as ‘feel

good’ countries today.

But not only has

American power and influence suffered a serious setback by now, the world order

is in disarray. One could even argue that in a world of sovereign states, the

lack of a dominant power that has the common interests of humanity at heart

leads to instability and conflict.

But today it is not

enough to reestablish the status quo that prevailed prior to 9/11, and

especially, no overhaul is possible without the participation, of the United

States. Tough we do not necessarily advocate the solution presented in the just

released “Terrorism, Human Rights, and the Case for World Government” by Louis P.Pojman, there is obviously a need for greater

international cooperation based on enforceable internationally. What we see

as more important however is a change of attitude from the single-minded

pursuit of national self-interest to showing some concern for the common

interests of humanity.

But how can we foster

democracy and deal with the likes of Saddam Hussein? How can we address nuclear

proliferation and global warming? How can we deal with the resource curse? How

can we keep the global economy on an even keel and reduce its iniquities?

Let’s start with the

first; In his second inaugural address, President Bush made the promotion of

democracy throughout the world the centerpiece of his program. Yet The Bush

administration's policies where full of contradictions. President Bush argued

against "nation building" in the television debate of the 2000

elections, and nation building was furthest from his mind when he ordered the

invasion of Afghanistan. Yet advocating democratization in other countries, it

failed democratic development in Afghanistan .

Or consider another

case, Pakistan . President Pervez Musharraf is a very uncertain and unreliable

ally: The top leadership of al Qaeda is hiding in Pakistan , and the resurgence

of the Taliban is supported by elements within Pakistan . President Musharraf

tells us that the choice is between him and the Islamic fundamentalists; with

Pakistan in possession of nuclear weapons, that makes the choice obvious. But

Musharraf is in alliance with the religious parties; that makes it difficult

for him to exert pressure on them. Little effort has been made to reform the

madrassahs, and the state spends less than two percent of its budget on

education. Even so, the religious parties would probably get only a minority of

the votes in free elections. The two moderate parties that alternated in power

when the military allowed elections have deep roots in society in spite of all

the efforts of the military dictatorship to destroy them. Musharraf dismisses

them as corrupt; but the military are no better. Musharraf himself is not as

popular as his supporters have us believe; that is why he refuses to carry out

his promise to stand for elections; that is why he has to rely on the religious

parties. This is a case where free elections could resolve what is presented as

an intractable problem. The real problem is how to persuade the military to

hold free elections. Egypt has some similarities with Pakistan , the major

difference being that in free elections the Moslem Brotherhood would gain a

majority.

Another issue is

nuclear proliferation, for example the lack of international resolve to move

quickly to stop proliferation activities, such as those of A.Q. Khan (a worse

case from that of Iran ), also cripples the international non-proliferation

regime. In these circumstances, the incentives tend to outweigh the

constraints. The more countries acquire nuclear weapons, the greater the

pressure on others to do likewise. Regional tensions and nuclear armament in

South and East Asia make nuclear weapons appealing for neighbors. Nuclear

modernization efforts by the world's two largest nuclear powers heighten the

perceived importance of nuclear weapons for national security. The inducements

may not be strong enough to push countries to actually violate the

non-proliferation treaty, but they have every reason to line up at the starting

line. That is where a number of countries are heading. In addition to North

Korea and Iran , countries such as Argentina , Brazil , and Japan are now

believed to have the capacity to use their peaceful nuclear technology to

produce weapons grade material if they chose to do so. Estimates are that,

outside the nine countries that have produced nuclear weapons, up to 40

countries could produce nuclear weapons if they were willing to devote the

necessary resources. Only the ever thinning taboo against nuclear weapons

possession remains between these nuclear-capable states and nuclear weapons.

Although the spread

of nuclear weapons constitutes a threat to humanity, the arguments for

non-proliferation are undermined by the fact that the nuclear weapon states

have not fulfilled their obligations under the non-proliferation pact: they

have made only very limited moves toward complete disarmament, as required by

Article VI of the NPT. Thus the situation is much more dangerous than at any

time in the Cold War, yet much less thought is given to the subject than during

the Cold War. The best brains are not engaged. Insofar as there is public

discussion, it is focused on weapons of mass destruction falling into the hands

of terrorists. This is obfuscation. The very term "Weapons of Mass

Destruction" is misleading, because it lumps together weapons with very

different characteristics. The most potent threat, in my opinion, is the

proliferation of nuclear weapons in the hands of states. That threat is not

receiving the attention it deserves.

There is little hope

for a solution while the United States is modernizing its strategic arsenal and

continuing to have plans to use nuclear weapons. A solution could only exist if

a new non-proliferation agreement was negotiated-a new non-proliferation treaty

that would put all nuclear programs under international supervision. It would

not deprive the United States and other states of their weapons, but it would

place them under international monitoring to ensure immediate detection if a

country decided to initiate the use of nuclear weapons. But since there are

plentiful amounts of highly enriched uranium already in existence, it is

possible for nations to acquire fissile materials without producing their own.

The other necessary treaty component must therefore implement international

control of the production and disposal of the fissile materials necessary to

build nuclear weapons. Such an arrangement would run counter to the prevailing view

that American sovereignty is sacrosanct but it could make the world, a safer

place.

The United States is

right to believe that Iran is hell-bent on acquiring nuclear weapons in

fact Iran has done nothing to discredit this notion. The world is heading

toward a confrontation. Only the timing is uncertain. As I mentioned in the

previous chapter, I believe it may be possible to reach an accommodation with

Iran but it ought not to permit Iran to become a nuclear power. Iran has been

the main beneficiary of the invasion of Iraq but if it overplays its hand it

may lose all the benefits. If Iraq deteriorates into a regional Shia-Sunni

confrontation, Iran is liable to be drawn into it. A commitment by the United

States to withdraw its troops could serve both as a threat (because it would

leave the United States free to bomb Iran 's nuclear installations) and as an

inducement to cooperate in a political settlement (because it would consolidate

the gains Iran has already made without risking them in a war.) Iran has

suffered greatly during eight years of fighting with Saddam Hussein and another

war may not appeal to at least some segments of the power structure. Giving up

the nuclear program may not be much of a sacrifice especially if the

international community were willing to enter into a new nonproliferation

agreement that would put all existing nuclear weapons under an international

regime and impose a freeze on all further development of nuclear capabilities.

If most of the world were lined up behind such a treaty, Iran would find it

difficult to resist, and if it did, preemptive action by the United States

would encounter fewer adverse consequences than at present.

As for world economy,

the financial authorities are reinforced in their belief that with proper

supervision financial markets can take care of themselves. However the global

economy has been sustained by a housing boom, that notably in the United

Kingdom and Australia , has subsided, with a soft landing. But there are

reasons to believe that the slowdown in housing prices in the United States

will see repercussions.

Combined factors

there are likely to ensure that housing prices, once they subside, will not

rise again soon. And if an initial soft landing turns into a hard one when the

slowdown does not end. A slowdown in the United States could be transmitted to

the rest of the world via a weaker dollar. This, as an illustration of the kind

of dislocation that are bound to occur, because the global economy is prone to

periodic dislocations and it will require international cooperation to keep

them within bounds.

Even in the absence

of a crisis there is something perverse in the current constellation: The

savings of the world are sucked up to the center to finance over consumption by

the richest and largest country, the United States . This cannot continue

indefinitely, and when it stops the global economy will suffer from a

deficiency of demand.

Furthermore a

community of democracies that would exercise the responsibility to protect is

an attractive idea in theory, but it has been disappointing in practice. The

idea was launched in the waning days of the Clinton administration, in the

summer of 2000, at a conference held in Warsaw . From the outset, the

initiative suffered because it was a product of the foreign ministries and

lacked support from the ministries of finance. As a result, the Warsaw

Declaration has remained an empty gesture; it would not even have made it into

the newspapers if France had not refused to sign it because it had been sponsored

by the United States . And during its recent meeting, in Chile in April 2005,

the community of democracies could not agree about endorsing the proposed Human

Rights Council. Many developing democracies were suspicious that the United

States would use the Human Rights Council to further its’ imperial goals’….

Finally in regards to

the resource question, developing countries that are rich in natural resources

tend to be just as poor as countries that are less well-endowed; what

distinguishes them is that they usually have more repressive and corrupt

governments and they are often wracked by armed conflicts. This has come to be

known as the resource curse.

It started with a

campaign launched in early 2002 called Publish What You Pay. It was supported

by a number of international NGOs, including Global Witness, which is grounded

in the environmental movement. The aim of the campaign was to persuade

oil and mining companies to disclose all the payments they make to individual

countries. The amounts could then be added together to establish how much each

country receives. This would allow the citizens of those countries to hold

their governments accountable for where the money goes.

The line of reasoning

that led to the campaign, however, did not survive closer examination. (That is

why I call it a fertile fallacy). Companies listed on the major stock exchanges

could not be legally compelled to publish country-by-country accounts. British

Petroleum had to back down, but along with Shell, has announced that it will

publish its payments in countries where the government allows it. Nigeria has

waived the confidentiality clause and asked companies to report their payments

individually. Other EITI adherents, including Azerbaijan , do not allow

individual reporting, but ask all operating companies to pool their payment

data for public reporting purposes. Azerbaijan , where British Petroleum is the

lead operator, has established an oil fund on the Norwegian model and adopted

EITI principles. Kazakhstan has also set up an oil fund and has signed on to

EITI. Advances were especially made in Nigeria , when after the reelection in

2003, of President Olusegun Obasanjo he embarked on far-reaching fiscal,

monetary, and banking reforms.

One obstacle to

further progress on the resource curse is China , and, to a lesser extent,

India . In its quest for energy and other raw material supplies, China is fast

becoming the sponsor of rogue regimes. It is the main trading partner and

protector of the military dictatorship in Myanmar . It feted President Islam

Karimov of Uzbekistan immediately after the massacre at Andijan, and it

conferred an honorary degree on President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe . It is the

main buyer of Sudan 's oil, and it hindered the work of the United Nations in

dealing with ethnic cleansing in Darfur . It extended a large credit to Angola

when Angola failed to meet the conditions imposed by the International Monetary

Fund.

No single measure is

sufficient to ease the crisis. Many different actions will have to be taken at

the same time, in addition to carbon-free coal, nuclear energy, wind, biomass,

and, of course, demand reduction. That is where the price mechanism can be

useful: A carbon tax combined with carbon credits would provide the economic

incentives to introduce the appropriate adjustments both on the demand side and

on the supply side. The Kyoto Protocol set targets for carbon emissions and

facilitated the trading of carbon credits. It was a step in the right

direction, but it did not go far enough.

The global energy

crisis is more complex than any other crisis. It is not a single crisis but a

confluence of disparate developments that have reinforced each other and

reached crisis point more or less at the same time. They endanger our

civilization in various ways. Global warming and nuclear proliferation are only

aspects of a more complex situation that threatens to deteriorate into global

disintegration. Although the core of the crisis is the tight supply situation

for oil, the developments that may bring about disintegration are mainly

political.

See our earlier

in-depth comment about what next with the tight supply situation for

oil:

Financial markets

often go to the brink and then recoil. Our political system is less

well-equipped to avoid disaster however. We have experienced two world wars and

wars have a tendency to become increasingly devastating. The threat of nuclear

war should not be minimized. Our current civilization is fuelled

by energy; the global energy crisis could create immense havoc.

The present

phase of the crisis is the outgrowth of misconceptions, including those related

to 9/11. Although we cannot rid ourselves of misconceptions, we can correct

them when we become aware of them. Perhaps the biggest mistake is for the

United States to think that it is powerful enough to deal with these problems

on its own. The competitive position of one state vis-a-vis the others is not

what matters when the viability and sustainability of the world order is at

stake. The prevailing view that the world order, like a market, will take care

of itself if left alone, is plain wrong. Global warming, energy dependency, the

resource curse, and the nuclear nonproliferation regime require international

cooperation.

Although the global

energy crisis demands international cooperation, we must be wary of going to

the opposite extreme and disregarding the national interests of sovereign

states. No matter what systemic changes are introduced, they need to take these

interests into account. Consider China . Until 1993, it was self-sufficient in

oil; now it imports almost half its consumption. Its share of the world oil

market is only 8 percent, but it accounts for 30 percent of incremental demand.

China has a genuine interest in harmonious development, although we are next

also exploring the alternative viewpoint meaning if, the current situation is

not properly handled the next WW might be between China and the US .

Today however, since

China has a serious energy-dependence problem as well as serious pollution

problems, it is a natural partner for developing alternative clean fuels,

particularly from coal, which is plentiful in China . But China is not a natural

partner in curing the resource curse. On the contrary, in its search for

alternative energy sources it has become a customer of rogue states in Africa

and Central Asia, a situation that is contrary to China 's interest in

harmonious development; but its leadership sees no alternative, particularly

after its bid for Unocal was rebuffed. It would behoove the United States

government to allow China to acquire stakes in legitimate energy companies, but

only if it cooperated in dealing with the resource curse.

Europe could lead the

way in energy cooperation. It is heavily dependent on natural gas and Russia is

its main supplier. The European Union imports 50 percent of its energy needs

and imports are projected to rise to 70 percent by 2020. Russia is by far the

biggest supplier of its imported oil (20 percent) and natural gas (40 percent).

And as we have seen before (the indicated presentation/link above), many EU

countries depend heavily on gas from Russia, which supplies 40 percent of

Germany's total demand, 65-80 percent of Poland's, Hungary's, and the Czech

Republic's demand, and almost 100 percent of the gas needs of Austria,

Slovakia, and the Baltic states. This makes Europe particularly vulnerable

because Russia has begun to use its control over gas supplies as a political

weapon. The story is a complicated one and I can give only a brief outline

here. When the Soviet system disintegrated, the energy sector was privatized in

a chaotic fashion. Devious transactions were perpetrated, like the loan for shares

scheme, and enormous fortunes were made. When Vladimir Putin became president,

he used the power of the state to regain control of the energy industry. He put

the president of Yukos, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, in jail and bankrupted the

company. He put his own man, Alexey Miller, in charge of Gazprom and pushed out

the previous management that had built a private fiefdom out of Gazprom's

properties. But he did not dissolve the fiefdom but used it to assert control

over the production and transportation of gas in the neighboring countries.

This led to the formation of a network of shady companies that served the dual

purpose of extending Russian influence and creating private wealth. Billions of

dollars were siphoned off over the years. The most valuable asset was the gas

of Turkmenistan which was resold by a company registered in Hungary at a

multiple of the price at which it was bought. While the ownership of Eural Trans Gas was never disclosed, the decisions to give

it contracts were made jointly by President Putin and the then-president of

Ukraine, Leonid Kuchma. I believe that was one of the reasons why Putin exposed

himself so publicly in backing Kuchma's nominee, Viktor Yanukovich,

for president of Ukraine in 2004. After the Orange Revolution, the contract with

Turkmenistan passed into the hands of Ros Ukr Energo, a company with shady ownership set up by Raiffeisenbank of Austria. At the beginning of 2006, Russia

cut off the gas supply to Ukraine. Ukraine , in turn, tapped into the gas that

was passing through Ukraine on its way to Europe. This forced Russia to restore

supplies to Ukraine; but in the subsequent settlement, Russia gained the upper

hand: It promised gas supplies at reduced prices through RosUkrEnergo for six

months, but Ukraine committed itself to fixing the transit fees for five years.

Mter six months, Russia will be able to exert

political pressure on Ukraine by threatening to raise gas prices. Russia

already exercises control over Belarus.

A more recent

example, since a few days ago, the Russian environmental agency, Rosprirodnadzor, is suing Royal Dutch/Shell, alleging that

the oil supermajor has violated environmental regulations and failed to submit

timely reports…

The net result is

that Europe is relying for a large portion of its energy supplies on a country

that does not hesitate to use its monopoly power in arbitrary ways. Until now,

European countries have been competing with each other to obtain supplies from

Russia . This has put them at Russia 's mercy. Energy dependence is having a

major influence on the attitude and policies of the European Union towards

Russia and its neighbors. It will serve the national interests of the member

states to develop a European energy policy. Acting together, they can improve

the balance of power. In the short run, Russia is in the driver's seat; an

interruption of gas supplies disrupts European economies immediately while an

interruption of gas revenues would affect Russia only with a delay. In the long

run, the situation is reversed. Russia needs a market for its gas and few

alternatives exist as long as Europe sticks together. Europe could use its

bargaining the opposite extreme and disregarding the national interests of

sovereign states. No matter what systemic changes are introduced, they need to take

these interests into account.

Consider China .

Until 1993, it was self-sufficient in oil; now it imports almost half its

consumption. Its share of the world oil market is only 8 percent, but it

accounts for 30 percent of incremental demand. China has a genuine interest in

harmonious development. It also has a serious energy-dependence problem as well

as serious pollution problems. Therefore, it is a natural partner for

developing alternative clean fuels, particularly from coal, which is plentiful

in China. But China is not a natural partner in curing the resource curse. On

the contrary, in its search for alternative energy sources it has become a

customer of rogue states in Africa and Central Asia, a situation that is

contrary to China 's interest in harmonious development; but its leadership

sees no alternative, particularly after its bid for Unocal was rebuffed. It

would behoove the United States government to allow China to acquire stakes in

legitimate energy companies, but only if it cooperated in dealing with the

resource curse.

Meanwhile, encouraged

by the energy shortage and America 's weakness, Russia is assuming an

increasingly assertive posture that goes well beyond energy policy. Russia has

sold Iran (through Belarus ) S300 anti-aircraft missiles and has refused to

rescind the sale in spite of strong U.S. pressure. The missiles will be

installed by the fall of 2006 and after that time it will be more difficult for

Israel to deliver a preemptive strike against the Iranian nuclear installations.

Russia has also granted Hamas a $10 million-a month subsidy to replace the

subsidy withdrawn by the European Union and is reported to be selling arms to

Syria . (See Sergei Ivanov, " Russia Must be Strong," The TVall Street Journal, January 11, 2006; and Sergei Lavrov,

" Russia in Global Affairs," Moscow News, March 10, 2006. "

Russia Helps Israel Keep an Eye on Iran," The New York Times, April 25,

2006 - Associated Press).

Russia seems to be

counting on the disunity and inertia of the West. Unfortunately, its

calculation may prove to be correct. Both the United States and Europe are

internally divided and far apart from each other; the European Union is held

together by bureaucratic inertia. The business community is also inclined to

seek individual deals with Russia rather than to demand certain standards of

behavior. There is an urgent need for the West to pull together. International

cooperation ought to extend beyond the immediate emergency. Global warming

requires a global solution, but the attitude of the Bush administration stands

in the way. On this issue, the American public is ahead of the administration,

and it ought to impose its views on the government.

The most pressing

task today therefore, is to agree upon a new non-proliferation treaty. The

present treaty is breaking down. Iran is determined to develop its nuclear

capabilities and if it is not stopped, nothing can stop a number of other

countries from doing the same thing.

A missile attack on

Iran in the current circumstances on the other hand, would be

counter-productive. It would consolidate public support for the current regime

and reinforce the determination of the regime to develop nuclear bombs. It

would unite the Moslem and much of the developing world against the United

States . It would render the position of the occupying forces in Iraq untenable

and it would disrupt the world economy without stopping Iran from eventually

having nuclear bombs. Both scenarios lead to disaster. The only way out is to

agree upon a more equitable non-proliferation regime that would have near

universal support. Iran would either agree to join such a regime or it could be

forced to do so without incurring the disastrous consequences that a missile

attack under the current circumstances would entail.

For updates

click homepage here