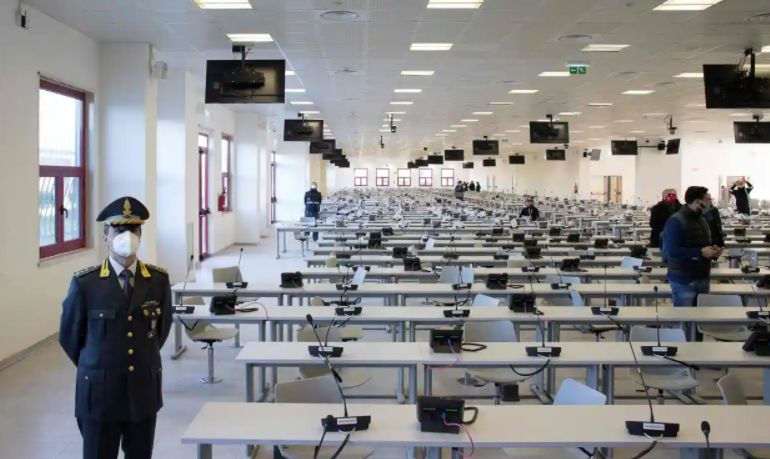

High-security

1,000-capacity courtroom has been built in Calabria, with cages to hold the

defendants

"The law is

equal for all" reads the title in Lamenzia

where Italy's biggest mafia trial in decades will start tomorrow, with

more than 300 defendants linked to the powerful crime group, the 'Ndrangheta,

to appear amid high security.

But there is an odd

aspect to this, Freemasonry. For example, the investigation conducted by

prosecutor Nicola Gratteri revealed a mixture of

'Ndrangheta, politics, and

Freemasonry.

The National

Anti-Mafia and Counter-Terrorism Directorate (DNAA) affirmed the enormous

interest of Cosa Nostra and 'Ndrangheta linked to Freemasonry,

indicating 193 subjects with double membership of which 122

from the Grand Orient of Italy; 58 to the GLRI, 9 to the GLI and 4 to the

Serenissima.

Calabria, the region

in the ‘toe’ of the Italian ‘boot’, is home to the Ndrangheta. Of all

the world’s gangster fraternities, the Ndrangheta has

the best claim to being global: it has colonies in northern Italy, northern

Europe, North America, and Australia. Regional and local government has been

beset for decades by organized criminal influence, and the dilapidated rural

communities of Calabria are home to some of Europe’s biggest drug traffickers.

The Ndrangheta is no mediocre mafia.

In October 2011, in a

farm building in one of those rural communities, police listening devices

recorded the local ’ndrangheta boss, Pantaleone ‘Uncle Luni’ Mancuso: ‘The ’ndrangheta doesn’t

exist anymore! … The ’ndrangheta is part of

Freemasonry … let’s say, it’s under Freemasonry. But they’ve got the same rules

and stuff … Once upon a time the ’ndrangheta belonged

to the rich folk! After, they left it to Giuliano Di Bernardo, the university

professor who, between 1990 and 1993, was the Grand Master of Italy’s biggest

and most prestigious Masonic order, the Grand Orient. In June 2019, speaking

through the beard that makes him resemble an Armani-suited Karl Marx, Di

Bernardo testified before a Calabrian court. He recalled his shock when, as

Grand Master, he looked into the state of Masonry in Calabria: ‘I discovered

that twenty-eight of thirty-two Lodges were governed by the ’ndrangheta.

So at that moment, I decided to leave the Grand Orient.’

Calabria has provided

plenty of fuel for conspiracist newspaper headlines that are as confusing as

they are inflammatory – along the following lines: ‘Mafia boss says,

“Freemasons run the ’ndrangheta!’” ‘Former Grand

Master confesses, “The ’ndrangheta runs the

Freemasons!”’ On 1 March 2017, on the orders of the permanent Parliamentary

Commission of Inquiry into the Mafia, police mounted dawn raids on the offices

of the four biggest Masonic orders, and confiscated membership lists. Their

search concentrated on Freemasonry in Calabria and Sicily, Italy’s most

notorious mafia hotbeds.

The raids by the

Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry brought back Masons’ memories of similar

raids twenty-five years earlier. At that time, a sprawling criminal

investigation had sought to map hundreds of criminal and wheeler-dealer

networks over the impossible tangle of different Masonic orders, Lodges, and

rites – both regular and irregular, open and covert. In 1993, the confiscated

membership lists were leaked, and Italy’s Freemasons were named in many

newspapers. Some Brothers reported receiving anonymous threats in the

aftermath; others said they were cold-shouldered by friends. (Strangely, the

lists in the press excluded all but a tiny number of the women Masons from

mixed orders.) Eventually, in 2000, a court in Rome halted the investigation,

declaring that it owed more to the ‘collective imaginary’ about Freemasonry

than it did to any evidence that Freemasons were infiltrating the public

institutions for illicit ends. Many dismissed this ruling as a cover-up. Masons

were left bitter.

Given this history,

in 2017 there was a complete breakdown in trust between the members of the

Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry and the Masonic leadership. The

Commission’s report accused the chief Masons of being in denial about mafia

infiltration, and of being ‘far from transparent and cooperative’: all four

Grand Masters had refused to hand over their membership lists. Soon afterward,

the Grand Master of the Grand Orient published a pamphlet that compared the

Parliamentary Commission to the Inquisition. (As coincidence would have it, the

Commission’s hearings are held in the same Roman palazzo where Galileo was

forced to recant his scientific findings.)

Yet there is a strong

sense that the Freemasonry’s dispute with the Commission of Inquiry was fueled

by political grandstanding from both sides. It is worth remembering that the

most senior Masons are elected: they are the Prime Ministers and Presidents of

their little democracies. Denouncing anti-Masonic prejudice and evoking the

memory of Masonic martyrs have always been rallying cries among the Brethren,

and thus a useful electoral gambit. On the other side, it would have taken a

strong-willed parliamentarian on the Commission of Inquiry to face up to the

public animosity towards the Craft. In February 2017, for example, Italy’s

leading current affairs magazine carried the front-page headline, ‘Let’s

abolish Freemasonry’. The populist Five-Star Movement, which came to power in

June 2018, has a policy of expelling Freemasons from its ranks, and Masons are

often listed among its ‘establishment’ enemies.

The Ndrangheta is a curious organization, having more than

twice as many members as Sicily’s Cosa Nostra, and a much more complicated

structure: for example, each stage in the career ladder of an Ndrangheta is marked by a new rank with its own

elaborate initiation ritual. The Calabria mafia is an underworld mirror of the

Craft, which blends local autonomy for the Lodges with national and

international ‘brand’ control. What we could call the Ndrangheta brand

or franchise, meaning its rules, ranks, and rituals, are all centrally

controlled by a body called il Crimine (‘the

Crime’). Even when they are based outside Calabria, ’ndranghetisti seek

authorization from the Crime to set up new cells. But the Ndrangheta is also decentralized, in that its

individual clans and cells pursue all kinds of criminal activities at their own

initiative. Nobody is answerable to the Crime when they smuggle in a shipment

of drugs, for example.

Things began to shift

in the 1970s when the Ndrangheta grew

vastly richer on the profits of kidnapping, narcotics, and infiltrating public

works contracts. As the money flowed in, the criminal brotherhood’s structure

evolved: unbeknownst to the mass of the membership, ever more upper ranks were

invented. By creating them, most senior bosses were trying to monopolize access

to the money derived from infiltrating public works, and keep the peace among

themselves while they did so. But they could never settle on a definitive

formula, just as at various times in the history of Freemasonry, there was

runaway inflation in the number of Degrees and rituals, and a fight over who

got to authorize them. Such internal wrangles were one of the reasons behind

savage Ndrangheta civil wars in the 1970s

and 1980s. In the end, around 2001, an alliance of the most powerful bosses

founded an entirely separate and highly secretive group within the Ndrangheta, so investigators believe. The group’s members

include men with the kind of white-collar, political skills needed to get on

with brokering corrupt deals with business and the state, while the crime

bosses were left free to use their own less specialized skills to best effect.

A few bosses who knew about this group have been bugged using various names to

describe it: ‘the invisible ones’, for example. And because, like everyone

else, Calabrian gangsters love to think of the Freemasons as the last word in

occult power, they also refer to the new group, according to one supergrass, as ‘something analogous to Freemasonry’.

That is what

the Ndrangheta boss Pantaleone ‘Uncle Luni’ Mancuso was doing when he was recorded in 2011 saying

that the Freemasons had taken over the Ndrangheta.

He was using a metaphor, as almost no one pointed out when Uncle Luni’s words were splashed over the newspapers.

But now is not the

time for the Freemasons of Italy to shout their outrage at the way their

reputation has been attacked because of a mere metaphor. The Gotha Trial may

yet hold damning surprises in store. It is also crucial to understand that

when Ndrangheta refers to Freemasonry they

are not just speaking in metaphor. Masonic Lodges, real Masonic Lodges, are

part of the Calabrian mafia’s pervasive networking system.

Here is how the

judges think it all works. The Ndrangheta loves

to get its hands on state contracts for collecting and disposing of rubbish,

building and maintaining roads and hospitals, and so on. ’Ndranghetisti use

mediators to wheedle their way into winning these contracts: politicians,

administrators, entrepreneurs, and lawyers. Indeed, mafia organizations are

only as strong as the mediators they can call on; they have a constant hunger

to co-opt new ones, and will use any mix of bribery, blackmail, and

intimidation to do so. This is where Masonic Lodges fit in.

Especially since

the P2 scandal, Freemasonry has attracted unscrupulous men from

the same kind of professional background as the honest Masons. Many of the

unscrupulous new arrivals get bored and go elsewhere when they realize what

honest Masons actually do. But within the confused world of Calabrian

Freemasonry, there are plenty of niches where clusters of them can find a base.

Most of the Lodges cited in the judges’ ruling in the Gotha Trial are the kind

of ‘covert’ or ‘irregular’ Lodges not authorized by the main national orders. They

act like dating agencies, matching ’Ndranghetisti to

mediators from among the professional classes, and can offer a route to the

very top of the grey zone where the criminal underworld meets the upper world

of politics and business. But regular Lodges are at risk too: by accepting a

banal favor from a Brother secretly in league with the ’Ndranghetisti ,

even an honest Mason can be drawn into a web of blackmail.

If the ruling of

the trial that starts tomorrow is right, then there is an obvious way that

the interests of Freemasonry could be harmonized with the fight against the

mafia. The main Masonic orders could seek the help of the law in policing the

boundary between regular and irregular forms of Masonry. Alas, no such approach

will be adopted any time soon. There are too few people on either side who have

an interest in collaboration. Masonry and anti-Masonry seem doomed to carry on

their centuries-old slanging match.

Prosecutor Nicola Gratteri (pictured in the center below) acknowledges

that Wednesday’s trial, which is expected to last a year, will not kill off the

crime empire, but he hopes it will mark an important step towards its demise by

encouraging victims to come forward and denounce the mobsters.

“It will open the

path to yet more trials and allow us to make even deeper inroads into the

group. I want people to believe in us and begin to collaborate and have ever

great trust in us,” he said.

For updates click homepage here