The View from

Germany

"We

began the war, not the Germans and still less the Entente – that I know."

With this admission, Baron Leopold von Andrian-Werburg, a member of the

tight-knit group of young diplomats influential in shaping Austria-Hungary’s

foreign policy in the last years of peace, began his memoir of July 1914.

However, as we have seen, in Berlin the possibility of a Balkan crisis was

greeted favorably by military and political decision-makers, for it was

felt that such a crisis would ensure that Austria would be involved in a

resulting conflict (unlike during the earlier Moroccan

crises, for example). When

Hoyos arrived in Berlin to ascertain the powerful ally’s position in case

Austria made demands of Serbia, he was assured that Germany would support

Austria unconditionally, even if it chose to go to war over the assassination,

and even if such a war were to turn into a European war. This was Germany’s

so-called “blank cheque” to Vienna.

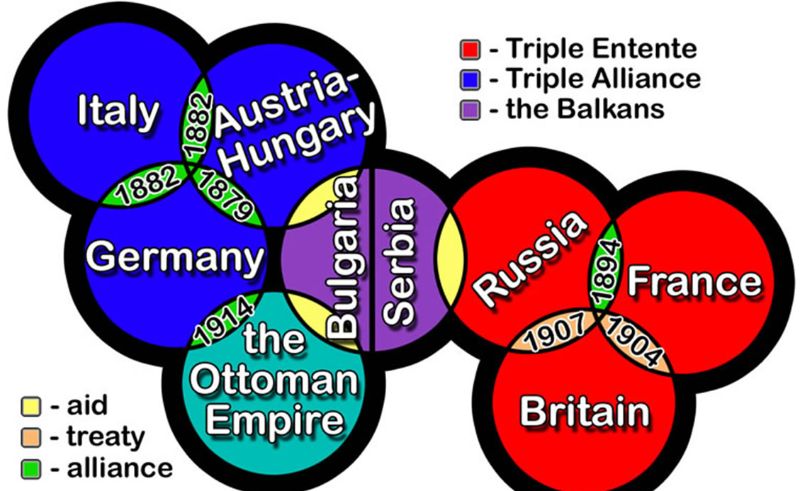

Historians have debated why Germany’s decision-makers decided to support

their ally come what may, and most historians today consider the “blank cheque”

a crucial step that led Europe into war. For the single most decisive moment in

Europe’s descent into war. In the calculations of Germany’s leaders, the crisis

was a golden opportunity to test the Entente which they perceived as encircling

Germany and its weakening ally Austria-Hungary. They were still confident that

war, should it break out, could be won by the Triple Alliance partners

(Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy), while in the long run, the Entente

Powers (Russia, France, and Great Britain) would become invincible. The worry

was in particular that Russia would increase its army and improve its railway

infrastructure to such an extent that shortly it would become impossible for

Germany to fight a successful war against Russia.

On the road to war which followed the assassination, the Hoyos Mission

was a crucial juncture at which the basic idea that only a war could bring

Austria's salvation became accepted in Vienna.

Armed with such reassurances from Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Joint

Ministerial Council decided on 7 July to issue an

ultimatum to Serbia.

When Alexander, Count of Hoyos chef de cabinet of the Foreign Minister

and László Szőgyény-Marich the Austro-Hungarian

Ambassador in Berlin arrived in Potsdam on 5 and 6 July 1914 bearing Emperor

Franz Joseph’s plea for support, Bethmann Hollweg, and the Kaiser had no

hesitation in assenting. The Chancellor is often characterized as being fatalistic

and resigned at this time due to the death of his wife two months earlier, but

this hardly fits with the purposefulness that he displayed. He and Wilhelm II

had met after news of the Sarajevo assassination reached Berlin. His admonition

to the Habsburg emissaries on 6 July that any action should be executed quickly

betrays a strategy already conceived. Bethmann’s plan was to exploit the crisis

to strengthen the Central Powers’ alliance and break the coalition surrounding

Germany. As he explained a few days later to his assistant, what was needed was

"a rapid fait accompli and afterward friendliness towards the

Entente." Bethmann recognized that due to Germany's only war plan which

included an immediate invasion of Belgium "an attack on Serbia can lead to

world war." Indeed, the British had warned the Germans of this explicitly

in December 1912 including Moltke in his famous 1913 memorandum.1 The Chancellor’s

complete surrender of the decision on how to proceed against the Balkan state

to Austria-Hungary was perhaps a subconscious attempt to avoid responsibility

for so monstrous an outcome, which he rightly foresaw would be cataclysmic. By

contrast, Bethmann was prepared to accept a continental conflict against Russia

and France. Moltke was confident that the army could win such a struggle, and

if Russia did intervene on Serbia’s behalf, German leaders considered that

would be better to act "better now than later."2

As pointed out before until the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was delivered

on 23 July, most European statesmen had been deliberately kept in the dark

about the nature of their plan by the decision-makers in Vienna and Berlin.

France, Russia, Britain, and Italy entered the stage late in July 1914, when most

decisions had already been taken.

The last Austro-Hungarian Common Ministerial Council of peace met

discreetly at Berchtold's home on 19 July. The ministers came in unmarked

vehicles, just one of many precautions they had taken to preserve secrecy.

Already five days earlier, Conrad and War Minister Krobatin

had ostentatiously taken leave to present the impression that no military

action was planned. The Viennese and Budapest press, whose sharp exchanges with

Serbian papers gloating over the royal murders had increased tension, had been

asked to avoid discussion of Serbia. The ministers wanted to take Europe by

surprise and forestall any attempt at mediation or deterrence.3

Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, while anxious to secure a peaceful

outcome of the Anstro-Serbian crisis, initially had a

"misplaced confidence in Berlin," believing that Germany would

moderate the Austro-Hungarian position. Thus not yet knowing what was brewing

as he put it on 20 July to the German Ambassador Prince Lichnowsky,

the whole idea that Serbia could drag any of the Great Powers into a war was

"detestable".4

From Balkan to World War

On 23 July Mateja Boskovic, the Serbian Minister in London, saw Arthur

Nicolson, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, telling him that

the Serbian Government was "most anxious and disquieted." Nicolson,

as yet unacquainted with the contents of the Austro Hungarian ultimatum, said

that it was "quite impossible to form an opinion," and so Boskovic

reported to Belgrade on 24 July that he had not been able to obtain any precise

indication of the position of the British Governrnent.5

That would start to change when on 27 July he read the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum "the most

formidable document I had ever seen addressed by one State to another".6

That day, Grey is known for his evenhandedness, Grey informed Crackanthorpe in Belgrade that Boskovic had

"implored" him (presumably through Nicolson) for a clarification of

the British attitude, but not wishing to "undertake responsibility",

he could only advise the Serbian Government to give a favourable

reply "on as many points as possible within the limit of time and not to

meet Austrian demand with a blank negative". This, he believed, was

"the only chance" of averting Austrian military action.7 Pasic, of

course, had already reached practically the same judgment.

Many of those who had been absent from the scene during the first days

of the crisis on 27 July were now returning to their duties at home or at their

post. The British ambassador to Germany, Sir Edward Goschen,

arrived in Berlin on Monday morning and immediately arranged to meet with the

secretary of state. That evening the French ambassador to Britain, Paul Cambon,

returned to London after a brief trip to Paris. San Giuliano returned to Rome

from Fiuggi Fonte. The French government announced that the president and the

premier had canceled the rest of their voyage and would arrive in Paris on

Wednesday.

Kaiser Wilhelm, against the advice of his chancellor, arrived at Kiel on

Monday morning. He then set out for the 200-mile railway journey to Berlin in

his private carriage, when he was intercepted by Bethmann Hollweg at Wildpark station in Potsdam. There, in the Kaiserbahnhof, the chancellor pleaded with him not to

proceed into Berlin: his sudden appearance there would make the situation seem

more ominous. The German government wished to maintain the impression that the

dispute concerned only Austria and Serbia and that Germany did not expect to

become involved. The Kaiser agreed and called for a meeting at the Neues Palais in Potsdam for 3 p.m.

As for Grey, not knowing about the blank Cheque, he believed that Berlin

could not afford to see its ally crushed, but warned that other Powers might

become involved for similar reasons if Germany entered the conflict, "and

the war would be the biggest ever known." For as long as German diplomacy

worked towards a peaceful settlement of the Balkan crisis, Berlin could count

on Britain's willingness to cooperate.8

When Prince Lichnowsky the German Ambassador

in London met with Grey that morning, he found him irritated for the first time

during the crisis. It was the German government, Grey complained, that had

requested he exert his influence to induce Russia to proceed with moderation.

This he had done and done so successfully. Now it was Germany's turn to exert

its influence at Vienna and get the Austrians either to accept the Serb reply

as satisfactory or at least as the basis for a conference. The resolution of the

crisis now lay in Germany's hands. He would be making a statement to this

effect in the House of Commons later in the day. Lichnowsky

now warned the Wilhelmstrasse that if it came to war Germany would no longer be

able to count on British sympathy or support. In London, they believed the key

to the situation was to be found in Berlin, where they had the power to

restrain Austria from proceeding with its foolhardy policy.9

Unfortunately, just the opposite happened. Germany's Secretary of State

Gottlieb von Jagow alerted Vienna to Grey’s suggestions. He made it however

clear that the German government did not identify themselves with the proposals

but merely passed them on. The wire to

London was not to be severed. Germany's Ambassador in Vienna H.L. Tschirschky thus had been informed of Grey’s initiative but

had not been instructed to submit the proposal to Berchtold.10

Jagow’s intimation to Szögyény, thus, amounted

to a second "blank cheque," this time to Tschirschky:

Vienna was to accept proposals of mediation only if encouraged to do so by the

German ambassador. Jagow’s intrigue, however, could only work with Tschirschky’s cooperation. The ambassador’s steps the next

day are certainly suggestive of some understanding between him and the state

secretary. For at that time, Tschirschky informed

Berchtold of the British mediation proposal and had not urged him to accept it.

Meanwhile, all Russian attempts to get Germany to intervene to slow the

Austrian plunge into war were met with claims that the conflict must be

localized, in other words, Russia had to leave Serbia to its fate.

Assurances that Vienna’s occupation of Serbian territory would only be

temporary were of no comfort; as Baron M.F. Schilling, Director of the Russian

Foreign Chancellery, commented, the Austrians had occupied Bosnia for thirty

years before annexing it. An additional worry was that a victorious Austria

could easily decide to bribe Bulgaria with Serbian territory, thereby winning

over Sofia for the Central Powers. Austrian treatment of Serbia would be a

strong warning to Romania that irredentist agitation had its risks and Russian

protection was a chimera. Meanwhile, the Young Turk leaders in Constantinople

would be confirmed in their existing view that Germany and its allies were the

most powerful force in Europe and that Turkey must seek their protection. Russian

diplomats in the Balkans and Constantinople made all these points. Faced with

this threat, the Russian government, not surprisingly, responded to Austria’s

declaration of war on Serbia with an order to mobilize the four military

districts facing the Habsburg monarchy. In this era of armed diplomacy, what

other means did Russia have to show serious intent to Germany and Austria? In

so doing, however, the Russians moved much further down the slippery slope that

led from rival military preparations to actual war.

Whitewashing the White Book

On 30 July it appears that Bethmann Hollweg's now was already planning

for when the German people would be given documented evidence on Russian

aggression. It is no coincidence that the German White Book - entitled

Germany's Reasons for War with Russia - was published just three days later on

August 2, and then presented to the Reichstag on August 3 (before Germany was

to invade Belgium and hostilities with France began).

The White Book contained excerpts from diplomatic correspondence to

demonstrate that Germany had behaved honorably throughout the crisis, that the

Kaiser and his government had done their best to mediate the dispute but that

Russian military preparations left them no choice but to act.

On this day Bethmann Hollweg begged the Kaiser to draft a reply to a

previous telegram from the tsar. If Russia now mobilized against Austria -who

had mobilized against Serbia- then the Kaiser's role of mediator "will be

endangered, if not made impossible." Bethmann Hollweg pleaded with the

Kaiser to recognize that, as this telegram would be a particularly important

document "historically," he ought not to express in it the fact that

his own role as mediator had now ended.

The Kaiser accepted the chancellor's advice. That afternoon he replied

to the Tsar in a telegram that Wilhelm drafted himself- in English. It closely

followed Bethmann Hollweg's suggestions. The essential point was that if Russia

mobilized against Austria, the Kaiser's role as a mediator would be

"endangered if not ruined." His final words, however, were starker

and more dramatic: "The whole weight of the decision lies solely on you[r]

shoulders now, who have to bear the responsibility for peace or war."12

Considering simple publishing logistics, the book must have been in

preparation throughout the previous week, when Berlin was supposedly seeking a

mediated solution. It is also not by accident that Exhibit 23 of the White Book

is Wilhelm's very telegram to the tsar that Bethmann-Hollweg notes will be a

"particularly important document historically."13

Also, in the White Book, the Telegram's time of sending is given as 1.00

am, July 30. However, it was actually sent at 3.30 pm Berlin time that day and

arrived in St. Petersburg only at 5.30 pm. The final version of the telegram

and the one appearing in the White Book ends: "the whole weight of the

decision lies solely on your [the Tsar's] shoulders now, who have to bear the

responsibility for peace or war." Given that Russian general mobilization

was not ordered until 5.00 pm, an earlier dispatch time had to be put on the

published document to make it appear that the Russians, despite being given

plenty of forewarning, had still aggressively moved to mobilization against

Germany. A "particularly important document historically" indeed.

Thus it is clear that in the case of Germany a preventive war was very

much contemplated. Their own contribution to the unfolding of the crisis,

according to Clark, was "their blithe confidence in the feasibility of

localization." It may reasonably be argued, however, that even such a

"localization," i.e., a war limited to the Balkans, was entirely

within Germany's power to prevent - what was the point of the Hoyos mission if

not to get permission from Berlin to start a local war? The smoking gun, denied

by Clark, in the story of July 1914 is to be found

in Bethmann Hollweg's refusal even to consider the scenario put to him by Count

Hoyos that Austria-Hungary would desist from attacking Serbia if Germany

considered the moment to be unfavorable. Or as Kurt Riezler

the top-level cabinet adviser who became the closest confidant and advisor to

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg wrote that; “At least people

must concede that he ‘staged’ it [the war] very well. Besides, the war, though

not actually willed, was

precisely calculated and broke out at the most favorable moment.”

Only by taking into consideration whether a government ‘pulls the

trigger’ - that is, whether it launches into full-scale combat with or without

a declaration of war - can it be established that a nation is bent on going to

war. And, the states that pulled the trigger in late July and early August 1914

were the Austro-Hungarian and German empires.

The fatalistic crossing of

international borders

As for Russia, in hindsight, we could say that the Tsar (who was very

hesitant) should have refused to listen to his generals, and not sign a general

mobilization order. However, in the case of Russia one also should acknowledge

that (in contrast to Germany) mobilization did not have to mean war, and Russia

continued to place its hope on mediation.

Alternatively, as the Tsar wrote to the Kaiser on 31 July as a response

to the above-mentioned telegram from 30 July: "We are far from wishing

war. So long as the negotiations with Austria on Serbia's account are taking

place, my troops shall not take any provocative action. I give you my solemn

word for this. I put all my trust in God's mercy and hope in your successful

mediation in Vienna for the welfare of our countries and the peace of

Europe."

On 1 Aug the Tsar send another telegram to his cousin in Berlin, which

he hoped might still avert war. In it Nicholas accepted that the Kaiser was now

compelled to mobilize, but requested from him the same guarantee that he had

given him - that mobilization did not mean war and that talks would continue

irrespective of the ongoing mobilization measures on both sides: "Our long

proved friendship must succeed, with God's help, in avoiding bloodshed."14

Again his telegram clarified that Russian general mobilization did not

need to mean war.

It was Austria-Hungary which was the first to declare war on another

country, namely Serbia. Mobilizations did not necessarily have to lead to war,

as Russia's statesmen were keen to highlight on many occasions (although this

did not apply to Germany, where in fact due to the constraints of the so-called

Schlieffen Plan it necessarily did), but declarations of war did lead to war -

and while some aspects of the July Crisis are a matter of interpretation, the

timing of the declarations of war is one of those rare 'facts' in history that

cannot be disputed.

In German propaganda like in the White Book and also often in the works

of historians like recently Christopher Clark's "The Sleepwalkers"

and Sean McMeekin's books, the fact that Russia was first to authorize general

mobilization is used as an argument for pinning responsibility on Petersburg

for the outbreak of war. At the time, this was an important means for the

German government to disclaim responsibility before its people and particularly

before German socialists. In so doing, it could play on the revulsion of

left-wing elements in the country for the tsarist regime and an older and

deeper current of fear in German culture about the threat of Russia’s barbarian

hordes. Subsequently, blaming Russia was a useful element in German rejection

of the war-guilt clauses of the Treaty of Versailles.

Yet there is a little truth in this accusation. By July 30 and 31, the

only way to avoid war would have been for Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to force

the Austrians to accept the British proposal for mediation. Given the mood in

Vienna, this could have been achieved only by a direct, sustained, and credible

threat by the chancellor to abandon Austria should it ignore German advice. In

reality, German pressure on Austria during these two days never amounted to

this. The impact of Bethmann Hollweg’s advice to the Austrians was also being

undermined both by the German ambassador to Vienna, Tschirschky

and by Moltke’s plea to the Austrian leadership to ignore the Chancellor and

plunge ahead into war. Had Bethmann Hollweg committed himself to threatening

the Austrians directly, it is by no means certain that the mercurial William II

would have supported him throughout the resultant furor. The Austrians would

have been justifiably outraged by what would have been a betrayal of the German

promise of unlimited support on which their whole strategy in July 1914 had

been based. If Wilhelm II had supported Bethmann Hollweg, then both men would

have been execrated for their weakness by most of the civilian and military

leadership in Berlin, not to mention by much of German public opinion. The

Russian general mobilization actually got Bethmann Hollweg off the hook and

allowed him to present the conflict to the German public as a war of defense

against aggressive tsarism. Inevitably, Russia’s mobilization was quickly met by

a German ultimatum, followed on August 1 by a declaration of war against

Russia.

However, if one concentrates on the July crisis, the responsibility for

the outbreak of war rests overwhelmingly on the shoulders of Berlin and Vienna.

German policy accepted enormous risks and made fundamental miscalculations, and

nevertheless, as these risks and miscalculations became clear between July 29

and July 31, it chose to plunge forward into war. It is true that even by July

29 diplomacy was becoming increasingly entangled by military preparations for

war. Even in this respect, Germany was most at fault. Only there did

mobilization require immediate declarations of war and the crossing of

international borders.

Bethmann Hollweg and the head of the German General Staff Moltke

believed that the First World War was above all a preventive war, designed to

forestall an inevitable future conflict against Russia in which Germany’s

chances would be much slimmer than at present.

However, this German paranoia was to a significant extent generated from

within, and it is not enough to explain this simply by Germany’s central

position in Europe and exposure to possible foes to east and west. Germany was

an extremely successful and powerful First World nation-state. Its elites ought

to act in many ways to have been less paranoid about the future than their

Austrian, Russian, and even British peers who were forced to grapple with the

truly awful challenges of ruling vast and multinational countries in the modern

era.

Nor was the international context by any means as irredeemably black as

German pessimists believed. If Russia was likely to grow in relative power,

France was certain to decline. Quite apart from long-term demographic and

economic trends, unless Berlin did something stupid, it was most unlikely that

the nationalist wave that had brought Raymond Poincaré

to power would retain its strength for long. Above all, there were the growing

strains in the Anglo-Russian relationship, which Berlin had noted in 1912–14 and

which were likely to worsen unless Germany did something rash to reunite London

and Petersburg. Policy makers in Berlin, for the most part, had accepted the

reality that they could not compete with Britain as regards naval power and

that colonial expansion was better managed in collaboration with London than

against it. The British and German economies were growing and integrating, to

their mutual benefit. Increasing Russian power was more likely to sway British

public opinion against Petersburg than toward it. Within even the Foreign

Office, those who inclined toward Russia because of fear of its threat to

British interests in Asia were likely to lose ground in the next decade to

advocates of a more “balanced” approach. It was inconceivable that Britain

would support any Russian aggression against Turkey, let alone against Austria

or Germany. Berlin’s decision to risk so much in 1914 made little sense unless

the German leaders were actually seeking to carve out a European empire as a

basis for future equality with the United States.

German War Aims

Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg spoke for broad sections of the military and

civilian elites (whose annexationism he later blamed for restricting his policy

options) when he repeatedly identified Germany's interest as "the free

development of our energies" so as "to extend the greatness of our

empire." (Bethmann mentioned "development" five times in his

actual Reichstag speech explaining why Germany was at war, Aug. 4, 1914.) On

the Continent, Germany's development could occur only at the expense of other

peoples.

Thus right from the beginning, General Molke

issued a draft permitting seizure of state property in Belgium, and four

categories of private property (means of transport, communication, arms, and

munitions). Moltke's draft aimed unabashedly at treating Belgium as a

"base of operations" to be exploited for the German army and, among

other things, called for deporting large numbers of the Belgian working class.

15

In fact, nearly 1.5 million Belgians were displaced by the German

occupation of their land, with impoverished refugees fleeing in every

direction. Some 200,000 ended up in Britain and another 300,000 in France. The

most, by far - nearly a million - fled to the Netherlands, but did not always

have an easy time in doing so. The German army constructed a 200km-long

electrified fence that claimed the lives of around 3,000 attempted escapees

during the war.

At the war's end, as Germany prepared to negotiate with the Allies, the

head of the legal division of the foreign office (AA), Johannes Kriege, advised

against offering to submit to a neutral investigation of the "Belgian

atrocities," because "then we will get the entire war reparations

dumped on us"- a view he would hardly have held had Germany had good

evidence of its claim.16

The lacking of moderation was in part because the Germans had persuaded themselves

that (example the White Book) they were victims of Allied aggression, and

consequently would gain generous compensation for having been forced to fight,

and in part, because they needed to secure their empire’s future military

position. With their armies advancing on Paris in the second half of August,

and the capitulation of France seemingly only weeks away, key sections of the

German economic, political, and military establishment saw the alleged

injustice done to the German nation as a license to rob and plunder. As the

Reichstag deputy of the Catholic Centre Party, Matthias Erzberger,

put it in a three-point program to the German chancellor on 2 September: The

slaughterous struggle … makes it an obligatory duty to take advantage of

victory … Germany’s military supremacy on the [European] continent has to be

secured for all time, so the German people are able for at least the next 100

years to enjoy unmolested peaceful development … the second goal is the removal

of Germany’s unbearable subordination to England’s perpetual domination in all

matters of world policy, the third the break-up of the Russian colossus. It is

for this price that the German people went into the war.17

In this spirit, the leading Rhenish-Westphalian industrialist August

Thyssen developed his plan for the future shape of Europe in late August 1914.

In the west, Germany would incorporate Belgium and the French departments of

Nord, Pas-de-Calais (including Dunkirk and Boulogne), Meurthe-et-Moselle with

its belt of fortresses, and, in the south, Vosges and Haute-Saône.

France would have lost virtually all of her iron-ore regions. In the east,

Russia would have had to cede her possessions in Poland, all the Baltic

provinces, the Don region with its capital, Odessa, the Crimea, and a large

part of the Caucasus, which would enable Germany to spread her sphere of

influence into Asia Minor and Persia. The realization of these aims would lift

Germany to the rank of a world power equal to the British empire.

The instant Imperial German breaches of treaty, convention, and

customary law during WWI signaled, first, a strong challenge to the existence

of this system and, second, Germany's estrangement from it. The uniquely strong

concept of military "necessity" held by military and civilian

leaders, suspended the laws of war upon the subjective judgment of military

officers.

It also was not just its trek across Belgium, but also its submarine and

automatic contact mine "blockade," its surprise use of poison gas,

its exemplarily rough treatment of civilians, the sinking of passenger ships

like the British liner Arabic killing forty-seven civilians or the French

passenger ship Sussex and so on, were all shortcuts designed to vault into a

position of world power without the breadth or depth of diplomatic power to do

so.

However, when it came to discussing German war crimes in the context of

Versailles, it is as if Germany suddenly could not speak the same legal

language as the rest of Europe. That loss of language measures the

distance the Kaiserreich had drifted away from the

community and its estrangement from the consensus that the community had

reached the limits placed on war by law.

1. A. Mombauer, The Origins of the First World

War: Diplomatic and Military Documents, 2013, p.92

2.This is among others,

the underlying theses of Gerd Krumeich's 2014 study about the July

Crisis:"In Wirklichkeit aber, so meine These, war

gerade der Anspruch der deutschen Regierung, class

der Konflikt unter allen Umstanden "lokalisiert" bleiben musse, eine grosse

Herausforderung aller internatonalen Gepflogenheiten

jener Zeit. Dahinter stand das Kalkul, herausfinden

zu wollen, wie weit Russland kriegswillig und kriegsbereit sei. Sollte Russland

fur Serbien eintreten -, dann gelte es fur Deutschend, "lieber

jetzt als spater" den ohnehin unvermeidlichen

Krieg mit Russland zu beginnen." Krumeich, July Crisis,2014, p.12 ff.

3. S. R. Williamson, Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World

War, 1991, pp. 200- 202.

4. British Documents, vol.II, no.68, Grey to

Rumbold, 20 July 1914

5. Vladimir Dedijer et all., vol.7/2, no.536,

telegram Boskovic, 24 July 1914.

6. British Documents, vol.II, no.68, Grey to

Rumbold, 20 July 1914-

7. British Documents, vol.II, no.102, telegram

Grey to Crackanthorpe, 24 July 1914

8. Tel. Grey to Goschen (no. 208), 27 July

1914, British Documents, XI, no. 176; see also Buchanan aide mémoire, 15/ 28 July 1914, Die Internationalen Beziehungen im Zeitalter des Imperialismus, ed.

Otto Hoetzsch (Berlin, 1931), V, no. 161; and tel. Fleuriau

to Bienvenu-Martin (no. 149, secret), 27 July 1914, Documents Diplomatiques

Française (3) XI, no. 156.

9. Lichnowsky to Foreign Office, telegram, 1.31 p.m., 27 July, Die

Deutsche Dokumente Zum Kriegsausbruch 1914, I, nr

258.)

10. Tel. Szögyény to Berchtold (no. 307, strictly secret), 27 July 1914,

Österreich-Ungarns Aussenpolitik von der Bosnischen

Krise 1908 bis zum Kriegsausbruch 1914 (ÖUA), ed. L.

Bittner, A. F. Pribram, H. Srbik

and H. Uebersberger, VIII, no.

10793.

11. Bethmann Hollweg to Kaiser Wilhelm, 11.15 a.m., 30 July,

Die Deutsche Dokumente, II, nr 408.

12. Kaiser Wilhelm to Tsar Nicholas, telegram, 3.30 p.m ., 30 July, Die Deutsche Dokumente, II, nr

420.

13. "White Book" on the outbreak of the German-Russian-French

War." The subtitle given in the English translation was: "How Russia

and her Ruler betrayed Germany's confidence and thereby made the European

War."

14. Tsar Nicholas to Kaiser Wilhelm, telegram, 2.06 p.m., 1 August;

received at Palace 2.05 p.m. [Central European time], Die Deutsche Dokumente, III, nr 546.

15. Helmuth von Moltke,

"Grundzüge über die militärische und wirtschaftliche Ausnutzung des

Königreichs Belgien," cited in Jens Thiel,

"Menschenbassin Belgien": Anwerbung, Deportation und Zwangsarbeit im

Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen, 2007, 37.

16. Cited

in Prince Max von Baden, Erinnerungen und Dokumente, Stuttgart, 1927, 458.

17. Cited in Fritz Fischer, War of illusions: German policies from 1911

to 1914, 1975, p. 518.

For updates click homepage

here