By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

The Wilsonian Moment

In part one, we gave a general

overview of the 1919 or "Wilsonian moment,” a notion that extends before

and after that calendar year, in part two,

issues like the Asian Monroe Doctrine, how relations between China and Japan

from the 1890s onward transformed the region from the hierarchy of time to the

hierarchy of space, Leninist and Wilsonian Internationalism, western and

Eastern Sovereignty, and the crucial March First and May Fourth movements, in part three the important Chinese factions beyond

1919 and the need for China to create a new Nation-State and how Japan, in

turn, sought to expand into Asia through liberal imperialism and then sought to

consolidate its empire through liberal internationalism. And in part four the various

arrangements between the US and Japan including The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact

in 1928 and The Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament of

1930. Whereby next we will analyze the actual path to war starting with the

American China policy the Manchurian Incident and why this led to an

ideological clash with Japanese Asianism.

The standard

"road to war” narratives explain that Japan's invasion of Manchuria in

1931 strained relations with the United States, a situation severely

aggravated by the empire’s invasion of China proper in 1937, and then brought

to a breaking point in 1941 by Japan's advance into southern Indochina In

response, the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt froze Japan’s

assets in the United States and placed a full embargo on oil. Japan’s leaders,

unable to find common ground with the United States, launched a surprise attack

oil Pearl Harbor. But if Japanese expansion into southern Indochina and the

subsequent oil ban provided the initial ‘'spark" of the Pacific War. then

what was the "gunpowder' that lay behind the belligerency? What explains

the underlying growing hostility between Japan and America in the 1930s? The

answer is crucial to understanding why the United States ultimately concluded

it had no option but to resort to freezing

assets and embargoing oil, and why Japan chose to abandon diplomacy and resort to war.

A prominent postwar

thesis stresses Japan’s "search for economic security" in Asia and

the construction of ail autarkic “yen bloc.” This “realist” perspective argues

that Japan's expansionism in the 1930s stemmed primarily from rational calculations

aimed at enhancing national security, in particular, the demand to secure

external markets and access to natural resources in an increasingly

protectionist world. Indeed, there was much talk in Japan at the time about the

nation’s alleged “have-not” status and unquestionable right to vital

"lifelines.” Explaining the Asia-Pacific War as a result of Japan’s drive

for autarky, and America's efforts to contain it, is an important part of the

story But it also tends to construct an image of a Japanese regime single-mindedly

focused on cold calculations of economic security. Underappreciated is how

these strategic pursuits were undergirded by an ideology profoundly at odds

with America’s core convictions about world order.

At the heart of the

conflict between the United States and Japan during the 1930s was the

importance of two competing ideologies of world order, liberal internationalism

and Pan-Asianist regionalism. From the Manchurian crisis of 1931 up through

fruitless negotiations in the fall of 1941 discord consistently turned on basic

principles about world governance, tied to rising geopolitical stakes. This

also includes the American reception of the Japanese government's efforts to

shape American public opinion in the 1930s through a vigorous program of

cultural diplomacy. By tapping the empire’s cultural riches or “soft power.”

Japan’s leaders hoped to combat negative perceptions in the United States and

legitimize their regionalist aspirations on the continent.

The American made China policy

The American mission to China in 1843-44, and the treaty of Wangxia that resulted from it was the reflection of a

strong and autonomous China policy; a policy that found another voice in the

Open Door notes a statement of principles initiated by the United States in

1899 and 1900 for the protection of equal privileges among countries trading

with China and in support of Chinese territorial and administrative integrity.

The statement was issued in the form of circular notes dispatched by U.S.

Secretary of State John Hay to Great Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Japan,

and Russia.

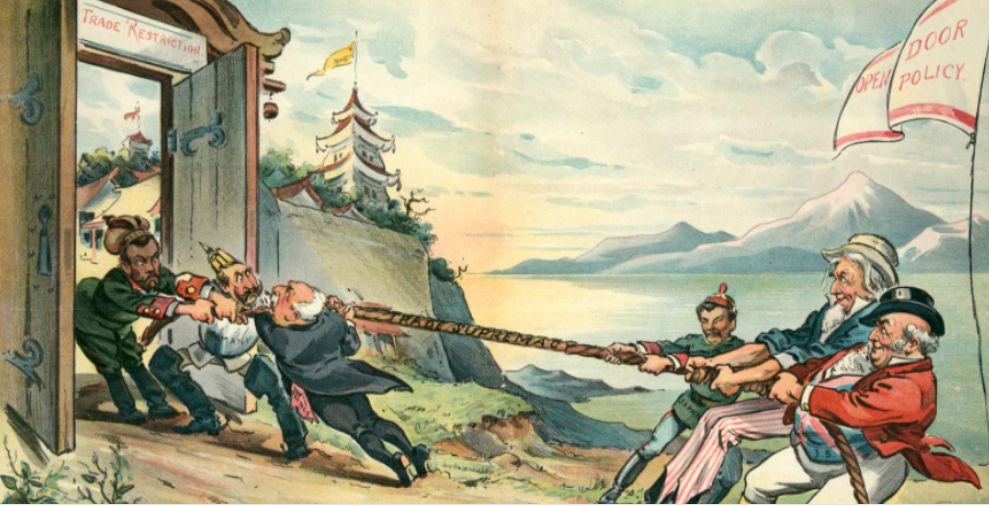

Underneath drawing

depicting the proponents of the Open Door policy (the United States, Great

Britain, and Japan) pitted against those opposed to it (Russia, Germany, and

France), 1898:

The 1899 Open Door

notes provided that each great power should maintain free access to a treaty

port or to any other vested interest within its sphere, only the Chinese

government should collect taxes on trade, and no great power having a sphere

should be granted exemptions from paying harbor dues or railroad charges.

Historian Yamamuro

Shin’ichi has drawn attention to the fact that it

was under the influence of World War I that two other streams of debate became

popular: one that ascribed to Japan a special role as mediator between the West

(“Euro-America”) and the East (“Asia”) in order to “harmonize” or “blend” the

two civilizations, and another that viewed a future clash between the East and

West as inevitable and demanded that Japan lead Asia in this anti-Western

enterprise. No matter which of the two streams one sided with, neither position

questioned the relevance or validity of the geographically, culturally, and

ethnically defined oppositional units, one of which was “Asia.” From the

mid-1910s onwards, such affirmative views of “Asia” began to displace

previously dominant attitudes among East Asians toward “Asia” as an

insignificant or derogatory category.

Since a larger

Asianist vision of the new world order was only realistic if China and Japan

agreed to cooperate, naturally, a key component within this debate was the

relations between China and Japan. But how could Japanese-Chinese cooperation

or, preferably, even friendship be achieved, given the strained bilateral

relations in the diplomatic arena, the fields of business and commerce, as well

as the growing antagonisms in everyday interactions between ordinary Japanese

and ordinary Chinese?

Ideology is an

elusive and expansive term. On one hand, the word is often used to describe a

particularly rigorous, comprehensive, and dogmatic set of integrated values,

based on a systematic philosophy, which claims to provide coherent and

unchallengeable answers to all the problems of mankind. Thomist Christianity,

Marxism-Leninism, and Nazism, one could suggest, all fall under this cloistered

meaning of ideology. Whereby in contrast to this one could also argue that

ideology is a set of closely related beliefs or ideas, or even attitudes,

characteristic of a group or community which comes closer to expressing a worldview

or mentally especially when as is the case here one is concerned with core

political beliefs and values related to a crucial normative question: how

should the international system be structured and managed? In the 1930s,

following a decade of general agreement. Japanese and American leaders held

distinctly antagonistic positions on tins question of world order. Simply

stated, the United States promoted a universalistic framework based on an

ideology of liberal internationalism, while Japan pursued an exclusive

regionalist arrangement with an emphasis on being the stabilizing force in

Asia.

The Sino-Japanese and

Russo-Japanese wars were important milestones in Japan's quest for world power.

With its victories over China and Russia, Japan proved itself as the most

formidable power in Asia. This was credited as the success of the Meiji Westernization

and reorientation of Japanese civilizational identity. Yet Japan could not

obtain recognition of its status from the West as an equal power in the

imperialist club. It became increasingly clear to the Japanese that race was

the major factor for its failure to, obtain such recognition. Despite Japan's

claim of carrying the flag of Western civilization in Asia, its expansion over

Asia caused a conflict of interests with Western colonialism.

Japanese Pan-Asianism

As we have seen, the mission to China in 1843-44, and the treaty of Wangxia that resulted from it was the reflection of a

strong and autonomous China policy; a policy that found another voice in the

Open Door notes a statement of principles initiated by the United States in

1899 and 1900 for the protection of equal privileges among countries trading

with China and in support of Chinese territorial and administrative integrity.

The statement was issued in the form of circular notes dispatched by U.S.

Secretary of State John Hay to Great Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Japan,

and Russia.

Then in 1936, Amau Eiji of the Japanese Foreign Ministry issued the Amau Doctrine, proclaiming Japan as the "guardian of

peace, and order in East Asia." In this role, Japan claimed the right to

oppose Western support to China and asserted that China did not have the right

to "avail herself of the influence of any other country to resist

Japan."1

This was a direct

challenge to the Open Door Policy declared by the U.S. Secretary of State John

Hay in 1899. Basically, the goal was to prevent any single power, most

particularly Japan, from gaining exclusive colonial control over China.

According. to this doctrine, all nations would have equal trading rights in

China and Western spheres of interest in China would not become colonial

possessions. In 1922, the Nine-Power treaty signed at the Washington Naval

Conference endorsed the open door policy and pledged mutual respect for Chinese

territorial integrity and independence. Hay stated in 1900 that "the

policy of the United States is to seek a solution which may bring about

permanent safety and peace to China, preserve Chinese territorial integrity and

administrative entity, protect all rights guaranteed to friendly powers by

treaty and international law and safeguard trade with all parts of

China."2 However, as other parts of Asia were already colonized by the

Western powers, Japan came to increasingly dislike the Open Door Policy as an

exclusive denial of its colonial expansion. In this context, ideas of an

anti-Western, Japan-centric Asian order gained currency among members of the

Japanese political and intellectual elite. The civilizational discourse of the

Meiji era was replaced by the racial discourse in the period of the war and

became hegemonic by the 1930s. The idea of a 'dobun doshu' ("same Chinese characters, same race") was

the basis of this version of Asianism. Yet common

culture and same race did not mean in the perception of Japanese Pan-Asianists

perfect equality of Japan and China. For them, "Japanese must assume the

dominant position in order to 'educate' and 'lead' the Chinese in the right

direction.3 Tokutomi Soho, once a quintessential liberal who converted to the

nationalist cause later, expressed these feelings: The countries of the white

men are already extending into the forefront of Japan. They have already

encroached on China, India, and Persia. Japan is not so far from Europe. Most of

the countries in the east from Suez, excluding Japan, have been dominated by

them. Coping with such a situation, can we have a hope of equal treatment

between the white man and the yellow man? No ... Although the Chinese, like us,

also belong to the world of the yellow man, they always humble themselves

before the white man and indulge themselves by leading a comfortable life. We,

Japanese, should take care of the yellow man in general, Chinese in particular.

We should claim that the mission of the Japanese Empire is to fully implement

an Asian Monroe Doctrine. „Although we say that Asians should handle their own

affairs by themselves, there are no other Asian people than the Japanese who

are entitled to perform this mission. Therefore, an

Asian Monroe Doctrine means in reality a Monroe Doctrine led by the

Japanese...We should end the dominance of the white man in Asia.”4

Leading thinkers from

a different political spectrum in China also showed concern about the new

discourse on “Japanese-Chinese friendship.” Chen Duxiu (1879–1942), together

with Li Dazhao (1889–1927), a co-founder of the

Chinese Communist Party (CCP), had studied in Japan in 1901 and was a leader of

the revolutionary New Cultural Movement.

Although both were highly critical of China’s traditionalism and, therefore, at

least potentially, shared some views held by Japanese debaters critical of

China, they rejected Japanese pressure on China to form an alliance in the

spirit of “Japanese-Chinese friendship” on Japanese terms. In March 1919, Chen

published a short essay in which he sharply rejected the demands from Japan to

receive special concessions in Shandong as a reward for its participation in

World War I on the victors’ side. “The countries that have fought together

heroically against Germany in the European War [World War I],” Chen wrote, “do

not demand Zambia or Poland as rewards. And yet, Japan, which frequently

advances ‘Chinese-Japanese friendship’ demands concessions for mining and

railways in Shandong province as a condition in exchange for the return of

Qingdao.

Japan's assistance to

the Chinese revolutionary movement led by Sun Yat-sen (1866 – 1925 who became

first president of the Republic of China and the first leader of the

Kuomintang-Nationalist Party of China) to overthrow the

Qing monarchy was a part of Japan's Asianist strategy. In a speech at a

girls’ school in Kobe on 28 November, he invoked the

vision of Pan-Asianism first raised by the exiles in Japan twenty years

earlier: the call for solidarity between peoples suffering the same sickness of

imperial domination.

Historian Yamamuro Shin’ichi has drawn

attention to the fact that it was also under the influence of World War I that

two other streams of debate became popular: one that ascribed to Japan a

special role as mediator between the West (“Euro-America”) and the East

(“Asia”) in order to “harmonize” or “blend” the two civilizations, and another

that viewed a future clash between the East and West as inevitable and demanded

that Japan lead Asia in this anti-Western enterprise. No matter which of the

two streams one sided with, neither position questioned the relevance or

validity of the geographically, culturally, and ethnically defined oppositional

units, one of which was “Asia.” From the mid-1910s onwards,

such affirmative views of “Asia” began to displace previously dominant

attitudes among East Asians toward “Asia” as an insignificant or derogatory

category.

Since a larger

Asianist vision of a new world order was only realistic if China and Japan

agreed to cooperate, naturally, a key component within this debate was the

relations between China and Japan. But how could Japanese-Chinese cooperation

or, preferably, even friendship be achieved, given the strained bilateral

relations in the diplomatic arena, the fields of business and commerce, as well

as the growing antagonisms in everyday interactions between ordinary Japanese

and ordinary Chinese? After Japan had issued the infamous

Twenty-One Demands to China, followed by boycotts and anti-Japanese protest

there, in 1915 and 1916 a first peak in Japanese proposals for friendship

between Japan and China could be observed. It was mainly driven by Sinophile

Japanese, such as Yoshino Sakuzō, Ukita

Kazutami, and Terao Tōru, but it also involved

Japanese critical of China and some Chinese who followed the debate closely.

Against the background of the ever worsening tensions between the two countries

in 1919, the “China problem” turned into a veritable “China crisis” following

the disputes between the Japanese and Chinese delegations at the Paris Peace

Conference over “Japanese special interests” in Shandong and the return of

formerly German possessions there to China. Interestingly, this crisis, which

again triggered massive anti-Japanese protests and boycotts in China, was also

the origin of the revival of calls for “Japanese-Chinese friendship.” While all

participants in this debate agreed on the importance of friendship between the

two countries and peoples, the measures to be taken to achieve this end were

contested and varied widely. Ultimately, the year 1919 represented a chance for

friendship and peace between China and Japan that was missed.

There also was a

Japanese proposal to deal with China and the conflict of interests in East Asia

which can be loosely termed an Asian Monroe Doctrine

which was a proposal by Ukita Kazutami,

a Kumamoto-born and Western-trained liberal thinker and professor of history

and politics at Waseda University. Ukita’s proposal had originally been published in September

1918 in the widely read Japanese journal Taiyō, of

which he had been a chief editorial writer. In his essay, Ukita

argued that Japan’s regional approach should be neither seclusion (such as

during the Tokugawa period) nor exclusionist (as some anti-Western proposals

for a Japan-controlled Asia by Tokutomi Sohō and others suggested), but inclusive and aiming for

gradual change. In what was one of the most original contributions to the

public debate on Japan’s Asia policy in the Taishō

period, Ukita advanced a voluntaristic and nonracial

conception of “Asians,” whom he defined as everyone who resided in Asia,

regardless of nationality or race. Based on this assumption, he argued for a

conservative interpretation of an Asian Monroe Doctrine that included the

advice to preserve or moderately revise the current status quo, but not to

radically change it. In other words, as opposed to Tokutomi

Sohō’s “old Asianism” and

other Japan-centered, imperialist conceptions of Asian Monroeism

that aimed at a “Japan-controlled Asia,” Ukita

rejected radical claims for a proactive Japanese regionalist engagement that

demanded the expulsion of Western powers in order to “regain as Asians control

of Asia.” Also in contrast to more Japan-centered conceptions, Ukita rejected a special role for Japan as Asia’s “leader”

(meishu), but instead argued that Japan must be “the

protector of the East” (Tōyō no hogosha).

This difference in terminology was quite important to Ukita

and went beyond the merely rhetorical level. Rather, it formed the basis for

his criticism of Japan’s own approach toward Asia and in particular toward

China. Ukita openly criticized “Japan’s aggressive

tacticians,” who were stuck in nineteenth-century attitudes of only talking

about “Japanese-Chinese friendship,” but who in reality kept on exploiting

China for Japan’s sole benefit. In the twentieth century, however, Japan needed

to revise its attitude toward China: “Rather than speaking ill of the

incompetence or stupidity of the Chinese, the Japanese themselves must first

reconsider their own psychological attitude towards China,” Ukita

wrote, and he recommended that Japan aim at forming an alliance with China

(Ni-Shi kyōdō). Ukita had

held Sinophile convictions for some time and never forgot also to hold Japan

responsible for the shaky state of Sino-Japanese relations. One year after the

outbreak of World War I and half a year after Japan had issued the Twenty-One

Demands to China, Ukita had already argued that the

main responsibility for solving the problems between the two countries lay on

the Japanese side, although he added that Japan “like an elder brother needed

to guide China just as in the past Japan learnt from its elder brother

China."5

Japanese activists

such as Miyazaki Toten assisted the efforts of helping Chinese revolutionaries

in the name of fighting the common enemy of the West.7 In Japanese

understanding of this new Asian order, there was no return to the

China-centered old Asian order. Japan had to be the center of Asia. Hence, the

Meiji perception of Asia in the Japanese imagination did not change in this new

period; Asianism refused to recognize Asia as the

equal of Japan. Japanese Asianists subscribed to a new Asian civilizational

order in which Japan as the central power was waging a war of independence on

behalf of all Asia. It should be noted, however, that Asianist ideology did not

exist in sharp contrast to the liberal ideology, particularly to the degree of

Japan's centrality. Or why the discourse of Japanese imperialism has changed

from the view that Japan had the right

to expand into Asia as a member of the "civilized" world so that it

was Japan's obligation to liberate Asia from Western imperialism by means of

invading it. There were times when the most Western-oriented and liberal

philosophers expressed Asianist ideas, while the most Asianist thinkers

expressed anti-Asian opinions. However, these two views did not stand in

complete opposition of each other in the mentality of many Japanese. For

instance, Fukuzawa Yukichi, the ideologue of Westernization who famously

advocated Japan's de Asianization, argued for

Japanese leadership (meishu) in Asia in the 1880s.

Regardless of their ideological orientation, Meiji intellectuals and

policymakers always agreed that Japan was superior to other Asian nations. In

this sense, the degree of Asianism was determined by

the degree of identification with the West. Japan's disillusionment with China

as a result of China's perceived inferiority against the West convinced

Fukuzawa Yukichi and many others to completely give up any perception of

civilizational common identification with the Chinese and Koreans. Japan

represented the contemporary civilization and was thus entitled to bring it to

Asians, if necessary by force. The model for this liberal imperialism was

provided by the West, who justified colonial expansionism under the pretext of

"civilizing mission." On the other hand, Asianists thought that Asia

could be united only under Japan's leadership. Hence they supported Japan's

expansion into Asia in order to unite, Asians against Western aggression. They

believed that Japanese aggression to achieve this goal did not mean the same as

the Western aggression was imperialism, while Japan represented Asian

civilization and it was its defender. It was in this context of the shift of

imperialist discourse that Asianist philosophy became highly popular. While

Fukuzawa was the architect of the transformation of the Meiji civilizational

identity, Okakura became the prime ideologue of Asian unity and sought a

civilizational authenticity in Japanese identity. The gist of Okakura's

indirectly political writings was the idea of a common Asian civilization. He

believed that Asian civilization was one single unit of which Japan was an

integral part. Although Okakura's views did not immediately become popular when

he published his books, they gained traction, as Japan and the Japanese psyche

slowly drifted away from the West under the influence of many factors explained

above. Okakura came from a highly surprising background to be the ideologue of Asianism. He grew up among English-speaking missionaries in

Yokohama and had a far better command of English than Japanese. He maintained

very strong links with the United States throughout his life, spending a

significant portion of his life in the United States and accepted positions in

elite institutions such as the Boston Museum of Art in 1904 and received an

honorary MA degree from Harvard in 1911. Perhaps it is also true that this

background saved him from a sense of inferiority against the West and allowed

him to confront the West with a stronger sense of self-confidence.8

The Manchurian Incident and Ishiwara's Pan-Asianism

Kanji Ishiwara (石原 莞爾, 1889 –1949) was the

mastermind of the Manchurian also called Mukden Incident when around 10:20

p.m. on September 18, 1931, Japanese troops based in southern Manchuria

dynamited a small section of a Japanese-owned railway outside of Shenyang

(Mukden) and blamed it on Chinese saboteurs The railway was part of the

1,400-square-mile Kwantung Leased Territory, which Japan administered through

the semi-governmental South Manchurian Railway Company, and which the Japanese

troops, known as the Kwantung Army, were there to protect. Although a southbound

train passed over the area without incident moments later, the alarm went out

according to plan. The Kwantung Army subsequently used the manufactured

incident as a pretext to launch attacks against Chinese troops with die intent

to extend Japanese influence in Manchuria.

Starting from the

Mukden Incident as a pretext Japan occupied Chinese territories and established

puppet governments.

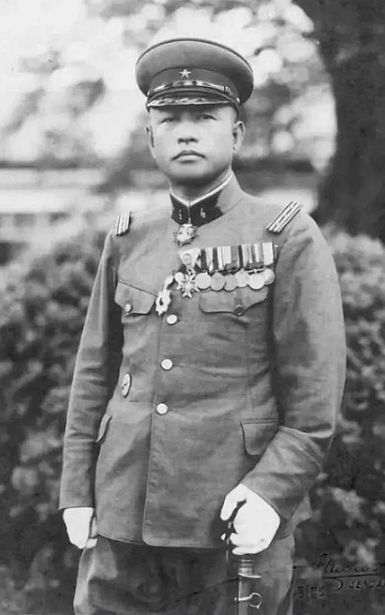

Ishiwara, Chief of

the Operations Division of the Japanese Army (as pictured below), argued that

Japan must avoid a war with China at all costs. Although he eventually yielded

to the opinion of the majority and authorized mobilization for the battle near

Beijing, Ishiwara continued to advocate a policy of cooperation with China,

for, in his mind, the Soviet Union was a greater menace than the strident

nationalism of Chiang Kai-shek's Nanjing government. Furthermore, he regarded

the development of Manchukuo and a cooperative relationship among Japan,

Manchukuo, and China as a precondition for the successful prosecution of an

eventual war with the United States, which

he held was unavoidable.

It was with this

vision of Pan-Asianism, a strategic alliance of Japan, Manchukuo, and China,

that Ishiwara initiated the foundation of Manchukuo’s leading institution of

higher education in the fall of 1936.

Ishiwara developed

his Pan-Asianism in the early twentieth century. During this period, following

Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5), Pan-Asianism especially the

idea that Japan must lead an Asian crusade against the West, gained popularity

not only in Japan but also in Asia when the ‘New Asia’ had

the imperial palace in Tokyo as its perpetual political and spiritual nucleus.

Pan-Asianism and Nichiren

Buddhism

This articulation of

Pan-Asianism arose from growing confidence in Japan as a model for indigenous

modernization that had rapidly advanced since the Meiji Restoration. In

contrast, Ishiwara’s perception of Pan-Asianism was rooted in a sober

conviction that militarism was essential to the future of Japan. He developed

this idea through his critical evaluation of Japan's victory over Russia. In

his judgment, Japan won the war out of luck; he believed that Russia would have

prevailed if the war was protracted because Japan had no clear plan for a

prolonged war.

Both Ishiwara’s 1919

discovery of Nichiren Buddhism and his observations

of China were of seminal importance for his thinking: he saw the disorder,

warlordism, and crime in China, causing him, like many other Army officers to

doubt China’s capacity to modernize on its own. But he was also critical of the

arrogant attitude of many fellow Japanese toward the Chinese people. At a time

when he also realized that Japan’s influence in China was opposed by the United

States, he also learned of Nichiren’s prediction of

an ultimate war followed by world peace. Soon he would put the two pieces

together, predicting that this ultimate war would be one between Japan and the

United States and that it would happen soon. In 1922, Ishiwara met the

religious philosopher and Nichirenist Satomi Kishio

(1897–1974), and after learning of the latter’s intention to visit Europe in

order to spread Nichiren Buddhism, Ishiwara decided

to take up earlier offers from the Army to go and study in Germany. Ishiwara

stayed in Germany from 1923 to 1925. He visited the battlefields and destroyed

towns of Northern France, and was shocked to see the morally devastated state

of Germany.

Ishiwara did not

simply use Nichiren’s words as an example to confirm

his theories of warfare. His belief in Nichiren and

the outcome of a new world Buddhist civilization and world peace was sincere

and anteceded his theory of war. The dynamic of world conflict followed by

world unity and peace followed the same pattern as the experience of World War

I followed by the creation of the League of Nations and a new ideal of

pacifism. Satō Kōjirō, it should be recalled,

predicted a similar trajectory of war followed by world peace.

Ishiwara’s next

concern thus was the rising US power in Asia, which he thought would eventually

clash with Japan. This apprehension led him to develop a theory of Final War.

According to this theory, the Japan-US confrontation was to be the final world

war that would divide the globe into two: the East led by Japan and the West

led by the United States. Ishiwara’s study of the Russo-Japanese War taught him

that Japan must prepare for this coming conflict, which he predicted would be a

prolonged war. How should Japan prepare? For Ishiwara, Pan-Asian unity was the

answer. He argued that Japan must expand its control over Manchuria and China

proper to strengthen its position geopolitically and to power its economic

expansion.

By the time of the

Manchurian Incident, thus, a more chauvinistic brand of Pan-Asianism permeated

Japan’s ruling class, one that combined resentment against the West with

condescension toward the East. Leading Japanese intellectuals, officials, and

opinion leaders self-consciously cultivated the "self-evident truth"

that Japan’s emperor-based polity was miparalleled,

that Japan was an exceptional nation, destined to lead and oversee Asia. In

some ways, this paternalistic strain of Pan-Asianism revived the underlying

rationale of imperialism’s “civilizing mission," in which an

''enlightened" power had a moral duty to elevate allegedly benighted

peoples. Ideologically loaded stock phrases subsequently carried the decade, in

particular, that Japan was “the stabilizing force” or “influence” in Asia. As

historian Eri Hotta has made clear, this ethnocentric strand of Asianism was not a mere “‘assertion.’ 'opinion.' or even

‘belief,’” but rather a "potent" and “pervasive” force among Japan’s

leaders By the 1930s the fundamental

premises of radical Pan-Asianism had come to be accepted by the mainstream of

Japanese society.

As competing

ideologies of world order in the 1930s. the differences between liberal

internationalism and Japan's more radical iteration of Asianism

were critical, and ultimately, irreconcilable. Although some scholarship has

pointed to areas of convergence between the two worldviews, for instance,

shared ideals of self-determination and autonomy, such congruency is compelling

mainly in comparisons between liberalism and the nondominating

strand of Asianism. The latter, however, was most

prominent among Japanese political elites around the turn of the century, not

the 1930s.8 What stands out are the fundamental differences. Again, central to

the premises of liberal internationalism was a reliance on so-called orderly

processes, with states pledging to abide by self-denying strictures, the most

hallowed of which was the repudiation of force in the pursuit of national

interest. In the event of conflict, nations were to settle their differences

within a cooperative framework, through frank discussion and arbitration,

either through the League of Nations or with signatories to multilateral

treaties.

When the US-Japanese war started

The Manchurian

Incident turned into an ideological crisis and a turning point in world affairs

and US-Japan relations. As the first real test ease for liberal

internationalism, the Manchurian crisis became the focal point of a tempestuous

ideological drama, in which Japan, the United States, and the League of Nations

debated the meaning and merits of the new diplomacy. Toward this end, we

discuss the Japanese government's guiding rationale for its seizure of

Manchuria, which includes the evolving premises of a more radical Pan-Asianism.

Japan's initial

endeavor hereby was to avoid isolation and win recognition of a new regionalist

framework justified by historical rights, strategic interests, and.

increasingly, an ideology of Pan-Asianism. Strategies by Japan’s Ministry of

Foreign Affairs included both official demarches as well as seemingly

“unofficial” diplomacy. including goodwill trips by eminent Japanese and an

emergent soft power campaign involving cultural propaganda. Despite a somewhat

scattershot approach, evidence suggests the Japanese government’s “charm offensive"

further propagated a “dualism" in American perceptions of Japan among the

press and Ambassador Grew', one that created an unrealistic turnaround in

Japan’s foreign policies.

After hostilities

erupted in North China in July 1937, Japan’s leaders issued strongly worded

Pan-Asianist statements and set out to realize an autarkic order on the

continent. The Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, meanwhile,

persisted in extolling the empire through cultural activities, including the

establishment of a cultural institute in New York. In Washington. President

Roosevelt, facing an isolationist Congress committed to neutrality, sought to

awaken Americans to the perceived threat of global war.

By 1939, Japan's

leadership focused on consolidating power on mainland China while

contemplating a closer relationship with Germany. In the United States.

President Roosevelt became vigilant in what became a kind of personal mission

to alert Americans to the perceived ideological convergence among revisionist

powers and the grave strategic threat they posed to the liberal democracies.

Confident of public backing, the administration notified Japan in July 1939

that it intended to terminate the US-Japan commercial treaty of 1911.

This then led to the

slippery slope to transpacific war. As would be the case through the attack on

Pearl Harbor, Germany's stunning victories emboldened Japanese expansionism,

which, in turn, stiffened American resistance. In September 1940. Japanese leaders

signed the Tripartite Pact, which foresaw “new orders" in Europe and

Asia. Tire pact’s stated intention of carving the world into hegemonic blocs

only confirmed the Roosevelt administration's global assumptions about the

existential threat resulting from the interconnectedness between ideology and

geopolitical ambitious among the Axis powers, hi 1941. protracted negotiations

between Japan and the United States revealed a yawning ideological gulf.

Although a number of Japanese leaders began to harbor doubts about going to war

against the United States, it was not because these men had abandoned their

dreams of a Japanese-guided regional order; rather, they believed that war

would undermine such aspirations. Regrettably, eleventh-hour negotiations could

do little to erase the fundamental ideological divide that separated the two

nations on the eve of Japan's surprise attack or alter the historical context

of the previous ten years.

After World War II,

the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers called upon Ishiwara as a witness

for the defense in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. No

charges were ever brought against Ishiwara himself, possibly due to his public

opposition to Tōjō, the war in China, and the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Concentrating on the

years of the Pacific War (1941-45), John W. Dower (1986) investigated the role

of race in Japan's wartime policy. In his thesis on the prominent role played

by race in igniting and intensifying war hatred on both sides, Japan and the

Anglo-American allies, one finds the author’s discussion of Japan’s race-based

Pan-Asianism. In analyzing the wartime reports written by governmental

bureaucrats, Dower identified the concept of the "proper place" as

the key to the Japanese racial view of the world. Based on the idea of the

racial purity of the Japanese, whose emperor supposedly descended from the Sun

Goddess, the Japanese official ideology held that the Japanese were destined to

dominate other peoples in Asia who belonged to lower places within a new

Pan-Asianist order. Gerald Horne (2004) similarly highlighted the vital role

that race-based Pan-Asianism played in Japan's initial military success in the

war against the allies. He has shown how Japanese propaganda efforts utilized

the local reality, Southeast Asian people’s strong resentment at white

supremacist racism under Western colonial rule, to

construct a Pan-Asianist message that Japan was a liberator of Asians. This

strategy proved effective, as Japanese troops were able to gain support from

the nationalists of each country. Such race-based collaborations against white

colonial regimes occurred throughout Southeast Asia, in Indochina (under French

rule), Singapore, Malaya, and Burma (under British rule), Indonesia (under

Dutch rule), New Guinea (under Australian rule), and the Philippines (under

American rule). Thus, Horne demonstrated how Japanese policymakers were keenly

aware of Western racism and used racialized Pan-Asianist propaganda to tap into

the anti-Western nationalist sentiments of peoples in the region.

American policy

toward Japan until shortly before the Pearl Harbor attack was not the

product of a rational, value-maximizing decisional process. Rather, it

constituted the cumulative, aggregate outcome of several bargaining games

which would enable them to carry out their preferred Pacific strategy.

Thus earlier we have

seen how Roosevelt's idea of a financial siege

of Japan in fact backfired by exacerbating

rather than defusing Japan's aggression. And for sure the attack on Pearl

Harbor was not the result of a deliberate Roosevelt strategy but a Roosevelt

miscalculation. Where by our taks in the following

part will be about a potential attack of China to take Taiwan in order to

expand its influence in the Pacific which China calls the

South China Sea.

Continued in part six

of; Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 1: Overview of

the discussions following the 1919 or "Wilsonian moment,” a notion that

extends before and after that calendar year: Part

One Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 2: Issues like

the Asian Monroe Doctrine, how relations between China and Japan from the 1890s

onward transformed the region from the hierarchy of time to the hierarchy of

space, Leninist and Wilsonian Internationalism, western and Eastern Sovereignty,

and the crucial March First and May Fourth movements were covered in: Part Two Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 3: The important

Chinese factions beyond 1919 and the need for China to create a new

Nation-State and how Japan, in turn, sought to expand into Asia through liberal

imperialism and then sought to consolidate its empire through liberal

internationalism were covered in: Part Three Can a

potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 4: The various

arrangements between the US and Japan, including The Kellogg–Briand Pact or

Pact in 1928 and The Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament

of 1930. Including that American policy toward Japan until shortly before the Pearl

Harbor attack was not the product of a rational, value-maximizing decisional

process. Rather, it constituted the cumulative, aggregate outcome of several

bargaining games which would enable them to carry out their preferred Pacific

strategy was covered in: Part Four Can a

potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 6:The war itself

quickly unfolded in favor of Japan’s regionalist ambitions, a subject we

carried through to the post-world war situation. Whereby we also discussed when

Japan saw itself in a special role as mediator between the West (“Euro-America”)

and the East (“Asia”) to “harmonize” or “blend” the two civilizations and

demanded that Japan lead Asia in this anti-Western enterprise there are

parallels with what Asim Doğan in his extensive new book describes how the

ambiguous and assertive Belt and Road Initiative is a matter of special concern

in this aspect. The Tributary System, which provides concrete evidence of how

Chinese dynasties handled with foreign relations, is a useful reference point

in understanding its twenty-first-century developments. This is particularly

true because, after the turbulence of the "Century of Humiliation"

and the Maoist Era, China seems to be explicitly re-embracing its history and

its pre-revolutionary identity in: Part

Six Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 7: Part Seven Can a potential future

Pacific War be avoided?

Part 8: While

initially both the nationalist Chiang Kai-shek (anti-Mao Guomindang/KMT),

including Mao's Communist Party (CCP), had long supported

independence for Taiwan rather than reincorporation into China, this started to

change following the publication of the New Atlas of China's Construction

created by cartographer Bai Meichu in 1936. A turning

point for Bai and others who saw China's need to create a new Nation-State was

the Versailles peace conference's outcome in 1919 mentioned

in part one. Yet that from today's point of view, the fall of Taiwan

to China would be seen around Asia as the end of American predominance and even

as “America’s Suez,” hence demolishing the myth that Taiwan has no hope is

critical. And that while the United States has managed to deter Beijing

from taking destructive military action against Taiwan over the last four

decades because the latter has been relatively weak, the risks of this approach

inches dangerously close to outweighing its benefits. Conclusion and outlook.

1. Dorothy J.

Perkins, Japan Goes to War: A Chronology of Japanese Military Expansion from

the Meiji Era to The Attack on Pearl Harbor (1868-1941) (Darby: Diane

Publishing,1997), 117.

2. Robyn Lim, The

Geopolitics of East Asia: The Search for Equilibrium (London: Routledge, 2003),

34.

3. Kazuki Sato,

"'Same Language, Same Race': The Dilemma of Kanbun

in Modem Japan," in The Construction of Racial Identities in China and

Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Frank Dikotter

(Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997), 131.

4. Susumu Takahashi,

"The Global Meaning of Japan: The State's Persistently Precarious Position

in the World Order," in The Political Economy of Japanese Globalization,

ed. Glenn D. Hook and Harukiyo Hasegawa (London:

Routledge, 2001), 24 On Tokutomi, see John D. Pierson, Tokutomi

SoM, 1863-1957, a Journalist for Modern Japan '

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980)

5. Toten Miyazaki, My

Thirty-Three Years' Dream: The Autobiography of Miyazaki Toten (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1982);

6. On this see Dick Stegewerns, Adjusting to the New World: Japanese Opinion

Leaders of the Taisho Generation and the Outside World, 1918-1932, 2007.

7. See Notehelfer, "On Idealism and Realism in the Thought of

Okakura Tenshin."

8. Hallet Abend

"Japanese Admit Ann to Hold Manchuria” New York Times, January 1 1932, 19,

Ki Tnukai. World's 1932 Hopes Voiced by Leaders/ New

York Times, January 3, 1932. 2 On emperor's reaction, see Bix. Hirohito,

246.

For updates

click homepage here