By Eric Vandenbroeck

Pacific Rising

In an article titled Beating

the ‘drums of war’ Australian defense minister Peter Dutton is quoted

as; “I don’t think it should be discounted” when asked about prospects of

Australia being drawn into a war with China over Taiwan. “People need to be

realistic,” he told the ABC.

Whereby it is not

only hardliners in Australia also Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand is becoming

more critical as she called on China “to act in the world in ways that are

consistent with

its responsibilities as a growing power.”

Fact is, the

prospects for war are actually higher in the next five years than the period

thereafter because of how successfully China has closed the military capability

gap with the US. Every day President Xi Jinping delays, his potential

adversaries in a battle over Taiwan (which would undoubtedly include the US,

Japan, Australia, and the UK) are investing enormous effort to prepare for war

and once again expand the capability gap.

Continuing with our

question can a potential future Pacific War be avoided as we have seen, China has become increasingly

frustrated with what it has considered a renegade province since the ruling

Democratic Progressive Party was formed in 1986 as a center-left, nationalist

organization. That frustration has grown sharply since 2016 with the (including

the later re-)election of President Tsai Ing-wen.

Nonetheless, the two

governments existed in an uneasy if prickly peace until US President Biden

in mid-April reassured Taipei by sending his first delegation led

by former Senator and personal friend of Biden Chris

Dodd to Taipei. A meeting between Biden and Japan's prime minister,

Suga Yoshihide, on April 17 then marked the first time since 1969 that the US

and Japan had issued a

joint statement mentioning Taiwan. This when Senator Chris Dodd

completed his three-day visit to Taiwan it was done with a

show of support from the Biden administration.

The Biden

administration entered office at a critical inflection point for the United

States. President Joe Biden inherited a world order and, an Indo-Pacific region

that is undergoing profound change with China’s rise and an ongoing

geopolitical shift toward Asia. The new administration has begun laying out its

agenda to address U.S. vital interests in this critical part of the world.

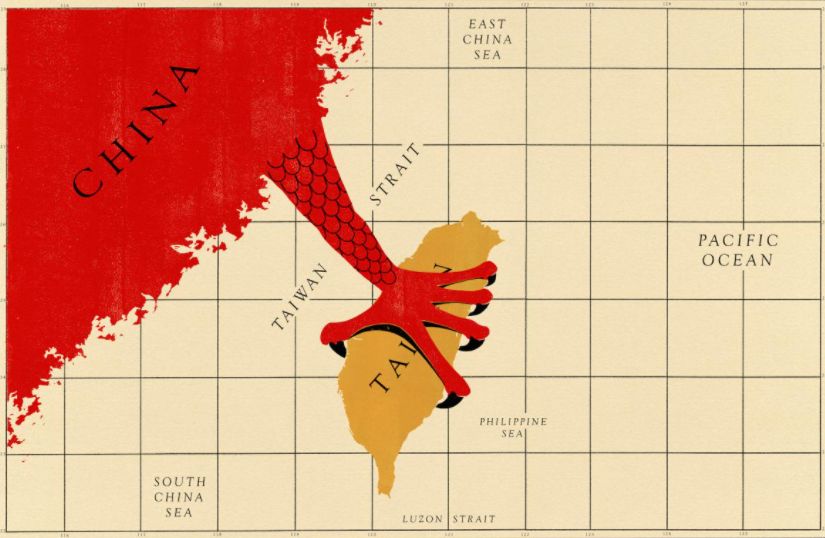

Within this broad

expanse, the Taiwan Strait is increasingly a critical military flashpoint.

Tensions are mounting as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) ramps up its

political, economic, and military pressure on Taiwan and its other neighbors.

There are warning signs that Beijing may be accelerating its plan to seize

Taiwan by force if necessary.

Biden’s strong start

regarding the Taiwan issue comes against the backdrop of China dramatically

increasing military activity in the waters and air space near the island. Data

released by Taiwan’s defense ministry shows that since the beginning of 2020, more

than 650 PLA warplanes have entered Taiwan’s southwest air defense

identification zone on their way to the Bashi Channel, the gateway to the

western Pacific and the disputed South China Sea.

All the while,

Taiwanese Foreign Minister Joseph Wu said that the island would defend

itself "to the very

last day" if attacked by

China. “We are willing to defend ourselves; that’s without any question,” Wu told

reporters. Adding that Taiwan-US relations undergoing major

adjustments.

Reiterated by Japan that seeks to

counter Beijing’s growing assertiveness in the East and South China seas.

Taiwan and a surprising Chinese history

Building on earlier

research like Lee Ji-Young's China’s Hegemony: Four Hundred Years of East Asian

Domination (2016) Tom Miller's China’s Asian Dream (2017)

in "Hegemony with Chinese Characteristics: From the Tributary System

to the Belt and Road Initiative" (April 2021) Asim Doğan explains

how China appears to be moving from a period of being content with the

status quo to a period in which they are more impatient and more prepared to

test the limits and flirt with the idea of unification also with Taiwan.

Having earlier

referred to the cartographic making of a Chinese Pacific, it is worth

asking what accounted for Taiwan to have become Chinese in the first

place?

Taiwan was never

involved with the Chinese tributary system; neither was the Chinese to any

large degree living on Taiwan until the Dutch importer them as laborers. On the

contrary, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) wrote:

"Overseas foreign countries… are separated from us by mountains and seas

and far away in a corner. Their lands would not produce enough for us to

maintain them; their people would not usefully serve us if

incorporated."1 As a result, he said, China would observe a strict Maritime

Prohibition (Haijin 海禁)2, a policy stipulating that all contact between

China and overseas foreigners must occur in official embassies, known as

tribute missions.3 No unofficial visits were to be tolerated. Nor were

Chinese allowed to sail abroad except, again, on tribute missions.

The Ming reluctance

to support overseas adventurers was not the result of an anti-imperialist

stance, for the Ming had had an active imperialist history. Still, although

China could have launched maritime enterprises that would have dwarfed European

attempts, Ming rulers generally did not consider maritime activity to be in

their interest, especially when it came to the support of private trade. The

Qing Dynasty, too, restricted foreign trade until the late seventeenth

century.4

Rather,

the Dutch, who in the 1630s realized that their port’s

hinterlands could produce rice and sugar for export. Still, they were unable to

persuade Taiwan’s aborigines to raise crops for sale, most were content to

plant just enough for themselves and their families.5 The colonists

considered importing European settlers, but their superiors in the Netherlands

rejected the idea. So they settled instead on a more unusual plan: encourage

Chinese immigration. The Dutch offered tax breaks and free land to Chinese

colonists, using their powerful military to protect pioneers from aboriginal

assault. They also outlawed guns; prohibited gambling (which they believed led

to piracy); controlled drinking; prosecuted smugglers, pirates, and

counterfeiters; regulated weights, measures, and exchange rates; enforced

contracts; adjudicated disputes; built hospitals, churches, and orphanages; and

provided policing and civil governance.6 In this way, the company, created

a calculable economic and social environment, making Taiwan a safe place for

the Chinese to move to and invest in, whether they were poor peasants or rich

entrepreneurs.7 People from the province of Fujian, just across the Taiwan

Strait, began pouring into the colony, which grew and prospered, becoming, in

essence, a Chinese settlement under Dutch rule. The colony's revenues were

drawn almost entirely from Chinese settlers through taxes, tolls, and licenses.

As one Dutch governor put it, "The Chinese are the only bees on Formosa

that give honey."8

Taiwan’s relative

standing reflected that knowledge within the Qing government of Taiwan’s

geography was so limited that it was not until the 1870s that serious efforts

began to govern most of the terrain. Similarly, an official handbook for Fujian

Province from 1871 presented a vague description for the location of Diaoyutai

– today a hotly contested site that also often gets the label of “an integral part of Chinese territory since

ancient times” and described it as a place where “over a thousand large ships”

could berth.

These opinions and

depictions do not suggest that Taiwan and its environs rose to the level of integral

territory for Qing-era Chinese. On the contrary, historians have shown that

popular and official discussion of Taiwan as a part of China, and formal

efforts to gain control of Taiwan by the government of the Republic of China

(ROC) and its ruling Nationalist Party, originated in the 1930s and 1940s, within the context of anti-Japanese sentiment and war.

After being chastened

by the Ming, the Dutch settled into a more docile role and were rewarded by the

Chinese trade, which flowed to their Asian outposts.9 When the Ming dynasty was

replaced by the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the Dutch were the first Westerners

to have an embassy in the imperial court. The Dutch ambassador raised no

objections to kowtowing. The Dutch even allied with the Qing, briefly, against

the remnants of the Ming dynasty, a mutual enemy. Hence two more Dutch

embassies were received in the court before 1700, each engaging in the standard

rituals.10

At the same time, the

Dutch ran an Asian court of their own in their colonial capital of Batavia

(present-day Jakarta, Indonesia). They received delegates from throughout Asia

and as far away as Africa, adopting the practices and trappings of Southeast and

East Asian diplomacy, such as parasols and parades of elephants. As historian

Leonard Blussé has noted, “the Batavian government

found its place among Asian rulers and learned to play by the rules of

what it then observed to be prevailing Asian diplomatic etiquette and protocol.

The Dutch colonizers literally had to invent ‘oriental’ ritual to stay in tune

with existing conventions for carrying out foreign intercourse at a diplomatic

level.”11

Thus were before the

1600s, Taiwan was self-governing, although there was no central ruling

authority. It was a colony of the Netherlands for about 40 years in the early

to the mid-17th century and was subsequently independent again for about two

decades. After which not Han Chinese but the Manchu-led Qing sent an army

led by general Shi Lang and annexed Taiwan in 1683. Qing rule over Taiwan then

ended abruptly when Taiwan was ceded to Japan by the Treaty of Shimonoseki in

1895. There were more than a hundred rebellions during the Qing period. The

frequency of rebellions, riots, and civil strife in Qing Taiwan led to this

period being referred to by historians as “Every three years an uprising, every

five years a rebellion.”

Previously China had

sat comfortably at the center of a ring of tributary relationships with its

neighboring countries. Its rulers had limited familiarity with any civilization

outside of Asia. In their few contacts with Westerners, they had made clear that

they expected the same deference from far-away leaders as they did from those

on their periphery. In this context see also: Imagining the concept of Han in the context of the civilized center and the

uncivilized lands on the periphery. Posted more than four years ago that

time we concluded that as for the People's Republic of China today, though

centered on Han Chinese, it is a multinational state modeled more closely on

the Manchu empire than on the Song or the Ming. Like the Manchu empire, its

territory includes Manchuria, part of Mongolia, Eastern Turkestan, Tibet,

Yunnan, as well as China Proper. Nevertheless, elements of the earlier Song

vision of the Chinese nation persist to the present day. First and foremost, as

mentioned, is the belief in the objective reality of a homogeneous Han people.

The sense that Chinese civilization is fundamentally Han at its core has fueled

the awkward relationship that continues to exist between the Chinese state and

its fifty-five non-Han minority nationalities. One also recognizes in the

twentieth century an enduring expectation of Han ethnic solidarity, whereby

both early twentieth-century nationalists and the People's Republic of China

have expected Han Chinese abroad (but not necessarily Uighurs or other minority

nationalities) to exhibit loyalty to their

motherland.

Whereby most

recently, in the space of a little over a century, China suffered a long list of

political, military, and cultural indignities.

Throughout the 19th

century, China was riven by massive rebellions in which tens of millions of

people died; these uprisings were frequently fanned by popular opposition to

the growing foreign presence and by the imperial government’s acquiescence to

foreign demands.

Independence

movements in Tibet, Mongolia, and Xinjiang in the 1910s, 20s, and 30s further

reduced China’s territory.

The millennia-old

imperial system collapsed forever in 1911, leading to an extended period of

further chaos in which the new, nominally republican government was unable to

control large swaths of China’s remaining territory.

The eight-year-long

war against Japan (World War II) and the multi-decade Chinese civil war between

the Chinese Communist (CCP) and Nationalist (KMT) Parties devastated the

Chinese landscape and tore its people apart.

Meanwhile within

Taiwan itself, officials and elites expressed strong opposition to the act of

incorporation into Japan’s empire and launched a number of rhetorical,

diplomatic, and military endeavors to prevent this colonial occupation.

However, some attempted to avoid colonization only by Japan and were amenable

to annexation by Britain or France instead. More significantly, at the end of a

two-year period in which, as stipulated by the Treaty of Shimonoseki that ended

the war, all Qing subjects residing in Taiwan had the opportunity to decide if

they would stay there or live in China, less than 10,000 out of roughly 2.5

million inhabitants had crossed over the Taiwan Strait. Thereafter, although

both violent and non-violent resistance to the Japanese colonial regime

remained a recurring feature of Taiwan’s history, it was couched in terms of

preventing either encroachment into indigenous lands or the eradication of

social and religious practices, and rarely if ever in the language of

reunification with China. Taiwanese remained interested in China, of course,

but as a source of inspiration for local cultural and political movements, an

ancestral homeland to be visited, or a site for lucrative business activities.

However, as the Taiwanese author, Wu Zhuoliu,

highlighted with the main character in his novel, “Orphan of Asia,”

many of the Taiwanese who went to China felt unwelcome there and disconnected

from it.

Several scholars,

including myself, have demonstrated the creation of distinctive Taiwanese

identities during the years of Japanese rule. Far from following the intentions

of Japanese assimilation policies, residents of Taiwan drew upon their cultural

heritage, new professional and labor associations, globally circulating ideas

of self-determination and participatory politics, and modern cosmopolitanism to

forge new identities. They displayed their new consciousness in calls for

independence from Japan, drives for voting rights and an autonomous legislature

for Taiwan within the Japanese Empire, and a wide range of social and cultural

behaviors, from local politics to social work to religious festivals. Some

inhabitants focused on nationalism and political independence, whereas others

concentrated on ethnic communities within a pluralistic political entity. These

behaviors clearly distinguished them from the Japanese settlers and the

colonial government that attempted to transform them into loyal Japanese subjects.

Instead, most of the population became Taiwanese, albeit in ways that excluded

Taiwan’s indigenous peoples.

They had not remained

Chinese, at least not as people and the government in China defined that term

during the early 20th century. became very clear to everyone on the scene soon

after the end of World War II. Although the rhetoric of the ROC government stressed

reunion and recovery and used the term “retrocession” (guangfu)

to describe Taiwan’s incorporation into its territory, government officials

looked upon the Taiwanese as people who had been tainted by Japanese influence

needed to be remade as Chinese citizens.

Those Taiwanese

themselves displayed genuine enthusiasm for the end of Japanese rule and the

arrival of Chinese civilian and military representatives in October 1945 but

quickly realized the vast distance between how they saw themselves and how the

new governing regime perceived them. They had forged their identities in

burgeoning modern metropolises and relation to modern capitalist industries,

and yet the Chinese government described them as backward. Those with roots in

China had centered religious practices in their new identities to resist

Japanese assimilation, and now the ROC government targeted those practices for

suppression as pernicious traditions. Even though many Taiwanese learned the

new national language of Chinese, as they had Japanese before, they felt no

connection to the national struggles and heroes that they were now told to

embrace.

These markers of

separation were evident before 1947 when the divergence between Taiwanese and

Chinese came into high relief during the 2-28 Uprising and its brutal

suppression by Nationalist Chinese military forces and the White Terror that

began soon thereafter. Political opposition to the Nationalist Party and

pro-independence sentiment went underground or overseas, but Taiwanese

identities intensified. However, sharp divisions continued to exist between

indigenous and non-indigenous populations; by the 1990s, many defined

“Taiwanese” to include both groups. Decades of single-party rule under martial

law by Chiang Kai-shek’s regime did not effectively instill most of Taiwan’s

residents with a new sense of Chinese national identity. Indeed, most of the roughly

1 million people who left China for Taiwan, and their descendants, came to

identify themselves with Taiwan, not China.

The “Century of Humiliation” and China’s National

Narratives

To be clear both the

Communists under Mao and the Nationalists used the

same Century of Humiliation narrative.

For the Nationalists

it served to delegitimize the Qing Dynasty, by

demonstrating its failure to ‘defend the country and thereby legitimize the

revolution.

Mao Zedong in his

famous proclamation speech announced that: Chinese have always been a

great, courageous, and industrious nation; they have fallen behind only in

modem times. And that was entirely due to oppression and exploitation by

foreign imperialism and domestic reactionary governments., Ours will no longer

be a nation subject to insult and humiliation. We have stood up.12

Whereby Deng

Xiaoping made the “one-hundred-year history of

humiliation”

post Tiananmen square central to the new source of legitimacy of the

CCP’s rule and the unity of the 'Chinese' people and CCP society and its yearly

National Humiliation Day.

Thus the intellectual

debates about the nature of international relations that took place during the

century of Humiliation underpin similar elite debates that are taking place in

China today. Concerns with the nature of interstate competition, with the possibility

for equality among nation-states, and with the question of whether the

international system might evolve into something more peaceable in the future,

remain salient topics of discussion and debate in China today.

Although the PRC

government maintains that the Century of Humiliation ended when the Maost CCP won the Chinese civil war and established itself

as the ruling regime; there remain several vestiges of that period that, in the

minds of many Chinese, must be rectified before China’s recovery will be

considered complete. The most important of these, and perhaps the only one that

is non-negotiable, is now the

return of Taiwan to the mainland.

Yet as we have seen

after ceding it to Japan, neither the Qing,

the Nationalists, or the Communists showed any interest in Taiwan. The Qing

court, the revolutionaries, and the reformists all took the same view: Taiwan

had been ceded by treaty and lost to China.

Surprisingly,

perhaps, the same insouciance about Taiwan’s fate also characterized the

revolutionary movement. Sun Yat-sen and his comrades made no demands for the return

of the island to Qing control. At no point, so far as we know, did Sun concern himself

with the resistance to Japanese rule, even though it continued to smolder. For

Sun, Japanese-controlled Taiwan was more important as a base from which to

overthrow the Qing Dynasty than as a future part of the Republic.

Also Chiang Kai-shek

(anti-Mao Guomindang/KMT) in his speech on ‘The Anti-Japanese Resistance

War and the Future of Our Party,’ Chiang Kai-shek argued that, ‘We

must enable Korea and Taiwan to restore their independence and freedom. Even more

so, Mao's Communist Party had long supported independence for Taiwan rather

than reincorporation into China. At its sixth congress in 1928,

the Guomindang party had recognized the

Taiwanese as a separate nationality.

Even more so, Mao's

Communist Party had long supported independence for Taiwan rather than

reincorporation into China.

This would change

shortly before the publication of the New Atlas of China's

Construction created by cartographer Bai Meichu in 1936 who later advised the Republic of

China government on which territories to claim after the Second World War.

A turning point for

Bai and others who saw China's need to create a new Nation-State was the Versailles peace

conference's outcome in 1919.

In an article

in the June 2013

issue of China National Geography, Shan Zhiqiang, the magazine's executive chief

editor, added: The nine-dashed line has been painted in the hearts and

minds of the Chinese for a long time. It has been 77 years since Bai Meichu put in his 1936 map. It is now deeply engraved in

the hearts and minds of the Chinese people. I do not believe there will be any

time when China will be without the nine-dashed line.

Bai and other

Chinese geographers took the nationalist idea of ‘territory’, lingtu( 領土 lǐng tǔ), and projected it back to the time of ‘domain’, jiangyu (降雨 jiàng yǔ) , when there were few fixed borders. A map of national

humiliation in Ge Suicheng’s 1933 textbook

showed vast areas of central Asia, Siberia, and the island of Sakhalin as

territory ‘lost’ to Russia. The map may have displayed different areas as

‘territory,’ ‘tribute states,’ or ‘vassal states’ but all were categorized as

inherently ‘Chinese,’ nonetheless. The idea that at the time they were ‘lost,’

these territories might have been contested areas with no clear allegiance to

any particular empire was not part of the lesson. They were presented simply as

‘Chinese’ lands that had been stolen. With a clear political purpose

behind the making of these maps Ge Suicheng called

on the young citizens reading his textbook to do what they could to recover all

this lost territory.

And while China has gained

an irreversible advantage in the South China Sea, at the end of the day,

the onus is ultimately on China to furnish an international law-compliant basis

for the alignment of its nine-dash line. Oblique references to history in its

1998 EEZ Act and 2011 Note Verbale to the United Nations, without

clarification of basis or scope, do not suffice. Rather they stoke justified

apprehensions that the line is instead an expedient tool that is wielded

opportunistically, and at times illegally, to punish other claimants’ presumed

non-neighborly activities in these contested waters.

At the end of the

day, the onus is ultimately on China to furnish an international law-compliant

basis for the alignment of its nine-dash line. Oblique references to history in

its 1998 EEZ Act and 2011 Note Verbale to the United Nations, without

clarification of basis or scope, do not suffice. Rather they stoke justified

apprehensions that the line is instead an expedient tool that is wielded

opportunistically, and at times illegally, to punish other claimants’ presumed

non-neighborly activities in these contested waters.

Conclusion and outlook

While early on, we argued that as Japan felt due to

earlier agreements with China, it felt justified to take Manchuria, not unlike

China perceives Taiwan and a large part of the Pacific (the South China Sea) as

their own. Similarly, when Japan saw itself in a special role as mediator

between the West (“Euro-America”) and the East (“Asia”) to “harmonize” or

“blend” the two civilizations and demanded that Japan lead Asia in this

anti-Western enterprise, there are parallels with our article posted on 14 April (most of which was written on

8 April) we exemplified that countless wars have revealed some historical

pattern: once a country’s territorial sovereignty conflicts with the hegemonic

system, it is only a matter of time before war breaks out. This is because both

parties are locked in an irreconcilable zero-sum relationship.

Whereby only a few

months before, America’s secretary of state, Dean Acheson, had declared that

“The Asian peoples are on their own, and know it.” But on 25 June, Stalinist North Korea launched an invasion of its southern neighbor,

and a country confronting communism could no longer leave Asia alone. America

would fight with South Korea. It was to join in that defense that

the Valley Forge was steaming north from Subic Bay.

Her route had added

purpose. Containing Asian communism meant more than fighting North Korea. It

also required making sure that Mao Zedong, mainland China’s ruler since the

previous year, did not take the island of Taiwan from the Nationalist regime

led by Chiang Kai-shek, who had been forced to retreat there. On June 27th

President Harry Truman announced a new Taiwan policy: America would defend the

island from attack; the Nationalists must, for their part, cease air and sea

operations against the mainland. “The Seventh Fleet will see that this is

done,” the president declared, with nicely laconic menace. Hence

the Valley Forge’s show of strength.

From that week on to

the relief of some and the frustration of others, Asian peoples were no longer

on their own. The Korean war transformed the region into a theatre of

ideological struggle just as fraught as divided cold-war Europe. For nearly

three decades, the Taiwan Strait saw ships of the Seventh Fleet acting as a

tripwire between the two Chinas. There were early battles over outlying

islands, including a crisis in 1958 in which Mao’s brinkmanship nearly started

a nuclear war. But over time, the rivals to the west and east of the strait

settled into an uneasy half-peace, both adamant that they were the one true

China, neither able to act on the conviction.

Over time Taiwan

became the prosperous, pro-Western democracy of 24m people, which it is today.

While the mainland saw traditions and social codes destroyed by Maoist

fanaticism, Taiwan has a rich religious and cultural life. It has come to enjoy

raucous free speech and a marked liberal streak: it was the first Asian country

to legalize gay marriage.

A generation ago, it

could matter greatly whether someone’s grandparents had arrived from the

mainland in 1949 or had deeper roots on the island. That has now changed,

especially among the young. In 2020 a poll by the Pew Research Centre, a

Washington-based research outfit, found that about two-thirds of adults on the

island now identified

as purely Taiwanese. About three in ten called themselves both Taiwanese

and Chinese. Just 4% called themselves simply Chinese.

Leaders in Beijing

differ; they consider them all Chinese. They tell their own people that most

citizens of Taiwan agree and that secessionist troublemakers egged on by

America are thwarting the historical necessity of national unification.

Once, Taiwan was a

point of compromise between the two powers. On January 1st, 1979, the day that

America recognized the People’s Republic of China, the economic reformers

running the mainland changed their Taiwan policy from armed liberation to

“peaceful reunification,” soon afterward adding a promise of considerable

autonomy: “one country, two systems.” But for the past 25 years, that

conciliatory offer has been accompanied by an unprecedented military build-up.

In recent years

China’s rhetoric towards Taiwan has sounded new notes of impatience. And the

crushing abnegation of its promise to observe “one country, two systems” in

Hong Kong has deepened Taiwanese distrust over the past two years. Last year

the issue helped Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (dpp) be re-elected president.

In principle,

the dpp favors the creation of a Taiwan

that is formally its own nation; but to declare independence in that way would

trigger massive Chinese reprisals. To keep that crisis at bay, Tsai, a

moderate, cat-loving academic, relies on an artful diplomatic dodge: that she

governs a country which, while proudly Taiwanese, uses the legal name of the

Republic of China which it inherited from the Nationalists who arrived in 1949.

China’s leaders detest her.

The passage of time

poses a dilemma for China. Every year, China’s ability to coerce Taiwan

economically and militarily grows greater. And every year, it loses more hearts

and minds in Taiwan. Should rulers in Beijing ever conclude that peaceful

unification is a hopeless cause, Chinese law instructs them to use force.

This dynamic alarms

the heirs of Dean

Gooderham Acheson. Though the accord of 1979 cast Taiwan into non-state

limbo, the island’s security remained,as a matter of American

law, a question of “grave concern.” When in 1996 China sought to intimidate the

Taiwanese, about to vote in their first free presidential election, using

missile tests, President Bill Clinton ordered the uss Nimitz,

a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, and her attendant battle group to pass through the strait. The

missile tests stopped.

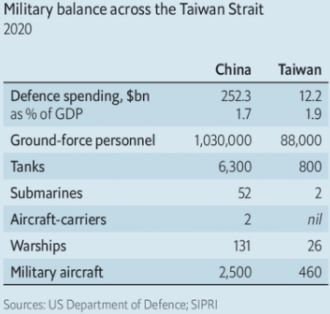

American military

commanders are increasingly open about their concerns that, in the context of

Taiwan, the balance of military power between China and America has swung in

China’s direction. A 25-year campaign of shipbuilding and weapons procurement,

begun in direct response to the humiliation of 1996, has provided the People’s

Liberation Army Navy (plan) a fleet of 360 ships, according to American naval

intelligence, compared with America’s 297. On 23 April, state media hailed the

symbolism of a ceremony in which China’s supreme leader, President Xi Jinping,

commissioned three large warships on the same day: a destroyer, a

helicopter carrier, and a ballistic missile submarine. The second is ideal for

airlifting troops to a mountainous island, the media noted with glee. The third

is a way of deterring superpowers.

America still boasts

more, better carriers and nuclear submarines. It has much more experience of

far-flung operations, and it has allies, too. But America’s forces have global

duties. China would be fighting close to home and enjoying the benefit of the pla’s land-based aircraft and missiles. Lonnie Henley, who

was until 2019 the chief Pentagon intelligence analyst for East Asia, sees the

radars and missiles of the integrated air-defense system along China’s coast as

the “center of gravity” of any war over Taiwan. Unless those defenses are

destroyed, American forces would be limited to long-range weapons or attacks by

the stealthiest warplanes, Henley told a congressional panel in February.

But destroying those defenses would mean one nuclear power launching direct

attacks on the territory of another.

And the Chinese

build-up continues apace. History is an imperfect guide, but offers precedents

to ponder, says a senior American defense official. “The world has never seen a

military expansion of this scale not associated with conflict.”

It is not just a

matter of numbers. China has carefully focused its efforts on the ability to

defeat American forces that might trouble it. It has missiles designed

expressly for killing carriers and others that would allow precision strikes on

the American base on Guam. The defense official lists other fields in which

China has worked to neutralize areas of American strength, whether that means

investment in anti-submarine weapons and sensors or systems to jam or destroy

the satellites on which American forces rely. Copying an American method, China

has set up a training center with a professional opposing force that mimics

enemy (in this case, American) doctrines and tactics.

The head of

Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Phil Davidson, told a Senate hearing in March

that China’s fielding of new warships, planes, and rockets, when considered

alongside the regime’s unblushing readiness to crush dissent from Hong Kong to

Tibet, makes him worry that China is accelerating its apparent ambitions to

supplant America and its allies from their position atop what he called the

rules-based international order, a phrase that China sees as code for Western

hegemony. Pondering the specific risks of a Chinese attack on Taiwan, the

admiral told senators that “the threat is manifest during this decade, in fact

in the next six years.”

Admiral John

Aquilino, nominated to be Admiral Davidson’s successor as head of Indo-Pacific

Command, told a confirmation hearing in March that work to shore up America’s

ability to deter a Chinese attack on Taiwan is urgent. While he stopped short

of endorsing his predecessor’s timeline of six years, he called the prospect of

Chinese use of force “much closer to us than most think.” Anxiety has been

raised further by war games involving Taiwan scenarios, both secret and

unclassified, that were won by officers, spooks, or scholars playing China's

role.

The admirals’ worries

mix judgments about China’s capabilities with hunches about its intent. Bonnie

Glaser of the German Marshall Fund, a public-policy outfit, notes that their

mission is to make plans, in this case, to win a war over Taiwan. Once they realize

that victory may elude them or may only be possible at great cost, panic is

understandable. That does not mean they are correctly assessing China’s

incentives to act soon. Strikingly, some of the intelligence officers paid to

analyze the world for admirals and generals are noticeably calmer. “The trends

are not ideal from a Chinese perspective,” says Mr. Henley. “But are they

intolerable? I don’t see them being in that grim a mindset.”

Broader American

angst is driven by the knowledge of what defeat would mean. Niall Ferguson, a

historian, recently wrote that the fall of Taiwan to China would be seen around

Asia as the end of American predominance and even as “America’s

Suez,” a reference to the humbling of Britain when it overreached during

the Suez crisis of 1956. But when Britain stumbled at Suez, America had already

taken its place as the Western world leader, Matt Pottinger told a

Hoover Institution podcast, “There's

not another United States waiting in the wings.”

For all its newfound

strength, China faces daunting odds. A full-scale amphibious invasion of

Taiwan, a mountainous island that lies across 130km of water, would be the most

ambitious such venture since the second world war. America has spent years

nagging its Taiwanese allies to capitalize on their natural insular advantages,

for instance, by buying lots of naval mines, drones, and coastal-defense cruise

missiles on mobile launchers to sink Chinese troopships, rather than continuing

to splurge on tanks and f-16 fighters. Randall Schriver, the

assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs in 2018-19,

promoted efforts to help Taiwan disable Chinese radar and other sensors: “If we

can just blind the pla, that would be a huge

contribution to the fight.”

If a Chinese

amphibious invasion of Taiwan were to fail, or military conflict to reach a

stalemate, would it fight on? Outsiders offer no consensus. Henley

suggests that a failed invasion might evolve into a long-term blockade, a

strategy to which Western defense planners pay increasing attention. There is a

much-heard view that once China starts fighting, anything short of victory

would mean regime-toppling humiliation.

The risks and costs

of war, even a successful one, bring home the point that capabilities in

themselves are never the determining factor. Intentions matter too and are far

more opaque, especially when, as in China, they reside largely in the mind of

one man. It is common to hear Western analysts state that Xi has staked

his legacy and legitimacy on Taiwan’s return. Hard evidence for this alarming

belief is in short supply. In a new-year speech in 2019, the most cited is that

he linked union with Taiwan to the ambition that he has placed at the core of

his leadership, namely the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” He also

repeated what he had said to a Taiwanese envoy in 2013: that cross-strait

differences should not be passed from generation to generation.

Having abolished the

term limit on his role as president in 2018, 67-year-old Xi can hardly expect

to be succeeded by another member of his generation. Following his own logic,

it falls to him to make sure that the task is not passed on. In an October 2019

meeting in Beijing, Chinese scholars and military experts shared with Oriana

Skylar Mastro of Stanford University their understanding that Taiwan must be

recovered during Xi’s time as leader.

Though some

semi-official Chinese commentators already say that they see no hope for

unification without some use of violence, there is no agreement among foreign

governments as to whether that is the settled view of China’s rulers. China

continues to try to shape Taiwanese opinion with a mix of sticks and carrots,

suggesting that negotiation has not been abandoned. The biggest carrot, access

to its vast markets, continues to be dangled in front of Taiwanese business

interests. Ms. Glaser notes that Mr. Xi sounded a patient note in March when he

visited Fujian, the coastal province nearest to Taiwan, urging officials to

explore new cross-strait integration and economic development paths.

But China’s carrots

and sticks can clash. To punish the Taiwanese for electing a dpp government, China has reduced official and

semi-official cross-strait contacts to “nearly zero,” says Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang, a former Taiwanese deputy defense minister, now

at the Chinese Council of Advanced Policy Studies, a think-tank in Taipei. That

raises the danger of misunderstandings.

So does China’s

increased military activity around the island. Psychological operations and

“grey-zone” warfare have been intensifying. In 2020, according to Taiwan’s

government, Chinese warplanes made 380 sorties into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone ((ADIZ)), a buffer zone of

international airspace where foreign planes face questioning controllers and

potential interception by Taiwanese fighters. Such a tempo of operations has

not been seen since 1996. On 5 April, the Chinese navy promised patrols by its

aircraft carriers around

Taiwan regularly. On 12 April, 25

Chinese planes entered the ADIZ, a record for a single day.

This may be a test of

the new Biden administration, says a senior Taiwanese diplomat, or a bid to

create a “new normal” in which Chinese forces are routinely present in a zone

formerly controlled by Taiwan. China knows that Taiwan will not fire first, so

“the Chinese will continue to push,” the diplomat says. The constant incursions

wear down Taiwanese defenses, raise the chances of accidental collisions, and

would make it harder to spot a rush to real war. Beyond the constant drumbeat

of military pressure, China is “trying to divide society, trying to sow the

seeds of chaos,” says the diplomat. “They also conduct cyber-activities and

disinformation campaigns.”

Wang Zaixi, a former deputy head of the Association for

Relations Across the Taiwan Straits, a semi-official Chinese body, advocates a

“third way” between all-out war and political negotiations massive display of

firepower cows Taiwan into submission. In Chinese media interviews, he has

cited the (not wholly reassuring) precedent of Red Army troops surrounding

Beijing in 1949 in such intimidating numbers that the city fell with rather few

casualties, an approach he calls “using

war to force peace.”

Meanwhile American

allies in the region emphasize how grim and frightening the Asia-Pacific would

feel if America ever broke its commitments and ducked a fight with China.

Japan’s prime minister, Suga Yoshihide, recently went further than any recent

predecessor when he mentioned the importance of stability

in the Taiwan Strait in a joint statement with Biden. Japan fears Taiwan

becoming a Chinese bastion just to its south.

Some in the US want

to make clear that maintaining its Asian role is central to America’s

interests, too. Senator Chris Coons of Delaware, a Democrat close to

Biden, is co-sponsor of the Strategic Competition Act, a bill with strong

bipartisan support that would

deepen ties with Taiwan, whether by offering the island trade deals,

weapons sales, expanded contacts with American officials or support in its

attempts to take part in international forums, as one of several measures to

push back against what he calls China’s growing global aggression.

It may sound a bit

narcissistic for Americans to assume that China’s plans for Taiwan turn on how

strong America looks to China. But Chinese experts and officials are sincerely

convinced that America is delighted to be Taiwan’s security guarantor and thus

gain a chance to meddle in China’s internal affairs. Without America to help,

Taiwan will surrender in an instant, they argue.

There is much to be

said for America’s decades-long policy of strategic ambiguity. Though some

American scholars believe it would usefully deter China to hear the Biden

administration say it would join any war over Taiwan, it could also provoke

China to rash acts or embolden some future leader on Taiwan to declare

independence. Logic also supports the Pentagon’s desire to spend the next ten

years arming Taiwan, buying new weapons, and increasing the uncertainty of

Chinese commanders and their political masters.

The challenge of such

an approach is to generate enough anxiety to stay China’s hand, but not so much

that Xi sees Taiwan slipping permanently from his grasp. For all the alarm in

Washington, China does not feel like a country on a war footing or particularly

close to one. Several sources briefed on a recent meeting in Alaska between

China’s top foreign-policy officials, Yang Jiechi and

Wang Yi, and the secretary of state, Antony Blinken, and national security

adviser, Jake Sullivan, report that the Chinese delivered shrill

and inflexible talking points on Taiwan, but used no new language that

showed unprecedented urgency.

A consideration in

the case of the US and also Australia of course is that the Chinese People’s

Liberation Army Rocket Force operates a host of ballistic missiles capable of

striking stationary targets across the Korean Peninsula and Japanese

archipelago. Its new DF-26 ballistic missile is assessed to have an operational

range of up to 2,500 miles, capable in theory of striking a moving aircraft

carrier and nicknamed by Chinese sources as “the

Guam killer” (Guam of course is where many US soldiers are stationed

including where the US weapons stockpile for the whole pacific including for a

possible defense of South Korea is located). The rest of Asia and northern

approaches to Australia are also covered by these same missiles.

China’s public stance

involves much saber-rattling, to be sure. Viewers of state television are never

far from their next sight of an aircraft carrier or gleaming jets screaming

through azure skies. But calls for sacrifice to prepare the public for full-on

hostilities are missing. The party’s claims to legitimacy in this, its

centenary year, are overwhelmingly domestic and based on order and material

prosperity: they are buttressed by images of gorge-spanning bridges and

high-speed trains, villagers raised from poverty, and heroic doctors beating

back covid-19 even as it rages around the outside world.

Nevertheless, China’s

visible capabilities and veiled intent are grounds for alarm. Its scorn for

Western opinion, as over Hong Kong, is a bad sign. The war over Taiwan may not

appear imminent in Beijing. But nor, shockingly, is it unthinkable.

How a potential future war about Taiwan can be

avoided

Since China considers

its over 2,000

missiles aimed at Taiwan

insufficient for deterring independence, and its huge market has not made

unification a more favorable prospect for the Taiwanese, China and the United

States are now locked in a security dilemma where China will increase military

coercion against Taiwan regardless of the nature of the support the U.S.

provides to Taiwan.

Xi however, should

soberly contemplate the downside of any adventurism now or in the future.

China’s economy slumped badly during the latest global downturn. Despite the

shrill propaganda, many citizens of China know the leadership in Beijing is

much to blame for this state of affairs. Enough of them have traveled to Taiwan

to understand the dramatic difference between them and presumably harbor some

sympathy for the free and democratic society across the strait.

Reflecting growing

bilateral ties, the United States and Taiwan should take further steps to

enhance “extensive, close, and friendly commercial, cultural, and other

relations.” This would be consistent with the language of the Taiwan Relations

Act and the Taiwan Travel Act, The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act (ARIA), and

the TAIPEI Act.

At that same time,

Taiwan must ensure its ability to integrate security efforts, including “hard

power” deterrence, across all threatened elements of national life and strength

to better respond to Chinese “sharp power” and protect Taiwan’s liberal values

and democratic institutions.

A strengthened

National Security Council operational role in integrating all elements of

national power and a fundamental armed forces redesign to meet today’s

challenge are also necessary. This demands a redesign of Taiwan’s national

security structure, a revised force structure, new automated training, and

professional military education systems, and new ways to ensure effective

deterrence.

Taiwan’s ground

forces must be integrated into the fight for air and sea supremacy. That

conclusion leads to what kind of weapons may be needed. A jointly developed

powerful simulation system is needed to test force structure options,

operational concepts, and doctrine to ensure effective deterrence and to

support improved training at all levels.

Cooperation with the

United States and other nations in the region that face the same threat is

essential. An Alliance of Democracies in the region and beyond must be

energized to support democratic ideals and demonstrate the appeal of

representative government to all captive populations in China and the region.

Demolishing the myth

that Taiwan has no hope is critical. The United States, along with its allies,

especially Japan, in close consultation with Taiwan, should develop a

coordinated messaging campaign to counter that narrative, resist coercion, and

strengthen deterrence.

While the United

States has managed to deter Beijing from taking destructive military action

against Taiwan over the last four decades because the latter has been

relatively weak, the risks of this approach inches dangerously close to

outweighing its benefits. Greater clarity and assurance of U.S. commitments to

defend Taiwan are critical for purposes of deterrence and stability.

Beijing as one

Chinese commentator wrote; craves too much respect. It wants to be feared and

loved. It may end up achieving neither.

Part 1: Overview of

the discussions following the 1919 or "Wilsonian moment,” a notion that

extends before and after that calendar year: Part

One Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 2: Issues like

the Asian Monroe Doctrine, how relations between China and Japan from the 1890s

onward transformed the region from the hierarchy of time to the hierarchy of

space, Leninist and Wilsonian Internationalism, western and Eastern Sovereignty,

and the crucial March First and May Fourth movements were covered in: Part Two Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 3: The important

Chinese factions beyond 1919 and the need for China to create a new

Nation-State and how Japan, in turn, sought to expand into Asia through liberal

imperialism and then sought to consolidate its empire through liberal

internationalism were covered in: Part Three Can a

potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 4: The various

arrangements between the US and Japan, including The Kellogg–Briand Pact or

Pact in 1928 and The Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament

of 1930. Including that American policy toward Japan until shortly before the Pearl

Harbor attack was not the product of a rational, value-maximizing decisional

process. Rather, it constituted the cumulative, aggregate outcome of several

bargaining games which would enable them to carry out their preferred Pacific

strategy was covered in: Part Four Can a

potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 5: The

Manchurian crisis and its connection to the winding road to World War II are

covered in: Part Five Can a potential future

Pacific War be avoided?

Part 6:The war itself

quickly unfolded in favor of Japan’s regionalist ambitions, a subject we

carried through to the post-world war situation. Whereby we also discussed when

Japan saw itself in a special role as mediator between the West (“Euro-America”)

and the East (“Asia”) to “harmonize” or “blend” the two civilizations and

demanded that Japan lead Asia in this anti-Western enterprise there are

parallels with what Asim Doğan in his extensive new book describes how the

ambiguous and assertive Belt and Road Initiative is a matter of special concern

in this aspect. The Tributary System, which provides concrete evidence of how

Chinese dynasties handled with foreign relations, is a useful reference point

in understanding its twenty-first-century developments. This is particularly

true because, after the turbulence of the "Century of Humiliation"

and the Maoist Era, China seems to be explicitly re-embracing its history and

its pre-revolutionary identity in: Part

Six Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 7: Part

Seven Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

1. Quoted in Chang

Pin-tsun, "Chinese Maritime Trade: The Case of

Sixteenth-Century Fu-chien" (Ph.D. diss.,

Princeton University, 1983), 14.

2. For a detailed

look at the intention of the

maritime prohibition and its

rules, see Bodo Wiethoff,

Die chinesische Seeverbotspolitik und der private Überseehandel von 1368 bis

1567 (Hamburg: Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens, 1963), esp. 27–50.

3. Much ink has been

spilled on the question of the Ming tribute system. A good early work is Wang

Gung-wu's "Early Ming Relations with Southeast

Asia: A Background Essay," in The Chinese World Order, ed. John K.

Fairbank (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968), 34–62. See also the

essays in The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1, ed. Frederick W. Mote and Denis Twitchett, vol. 7 of The Cambridge History of China, ed.

Denis Twitchett and John K. Fairbank (New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1988); and William Atwell, "Ming China and the

Emerging World Economy, c. 1470–1650," in The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644,

Part 2, ed. Frederick W. Mote and Denis Twitchett,

vol. 8 of The Cambridge History of China, 376–416. I have found especially

useful Chang Pin-tsun, "Chinese Maritime Trade:

The Case of Sixteenth-Century Fu-chien"; and

Bodo Wiethoff, Die chinesische Seeverbotspolitik.

J. K. Fairbank and S. Y. Teng's classic work on the Qing tribute system also

contains important information about the Ming system: J. K. Fairbank and S.Y.

Teng, "On the Ch'ing Tributary System," Harvard Journal of Asiatic

Studies 6, no. 2 (1941): 135–246. An interesting article about overseas Chinese

who accompanied tribute missions to China is Chan Hok-Lam, "The ‘Chinese

Barbarian Officials' in the Foreign Tributary Missions to China during the Ming

Dynasty," Journal of the American Oriental Society 88, no. 3 (1968):

411–18. For an argument about the effects of these prohibitions on southeastern

China's economy, see William G. Skinner, "Presidential Address: The

Structure of Chinese History," The Journal of Asian Studies 44, no. 2

(1985): 271–92. Skinner perhaps overemphasizes the role of Portuguese traders

in reinvigorating the region's trade.

4. The Qing decision

to open the seas came in 1683, after the capture of Taiwan from the Zheng

regime. It was a momentous policy, causing changes throughout East and

Southeast Asia.

5. This appears to

have been less true of cultures in the far south of Taiwan and in the

northeast, around today's Yilan (宜蘭), where sizeable rice surpluses were produced.

6. An overview of the

legal and administrative structure of the Dutch colony can be found in a

brilliant article by a young Taiwanese scholar: Cheng Wei-chung

鄭維中. “Lüe lun

Helan shidai Taiwan fazhi shi yu shehui

zhixu” 略論荷蘭時代台灣法制史與社會秩序, Taiwan Fengwu 臺灣風物, 52(1) [2002]: 11–40. See also C. C. de Reus,

"Geschichtlicher Überblick der rechtlichen Entwicklung der Niederl. Ostind. Compagnie," in Verhandelingen

van het Bataviaasch Genootschap der Kunsten en Wetenschappen (Batavia: Egbert Heemen,

1894).

7. The concept

"calculability" is at the heart of Max Weber's important work General

Economic History, trans. Frank H. Knight (New York: Greenberg, 1927). The

much-discussed Protestant Ethic is only a minor part of Weber's general theory

of capitalism, which focuses on institutions and practices that impede or

foster calculability.

8. Governor Nicolaes Verburch to Batavia, letter, VOC 1172: 466–91, quote at

472; cited in De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia, Taiwan,

1629–1662 [The journals of Zeelandia Castle,

Taiwan, 1629–1662], ed. Leonard Blussé, Nathalie

Everts, W. E. Milde, and Ts'ao Yung-ho, 4 vols. (The

Hague: Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis,

1986–2001), 3:96–97.

9. Leonard Blussé, “No Boats to China. The Dutch East India Company

and the Changing Pattern of the China Sea Trade, 1635–1690,” Modern Asian

Studies 30 (1) (1996): 51–76; Leonard Blussé,

“Chinese Trade to Batavia during the days of the V.O.C,” Archipel

18 (1979): 195–213.

10. Young-tsu Wong, China's Conquest of Taiwan in the

Seventeenth Century: Victory at Full Moon, 2017, pp. 111–113.

11. Leonard Blussé, “Queen among Kings: Diplomatic Ritual at Batavia,”

in K. Grijns and P.J.M. Nas, eds., Jakarta-Batavia:

Socio-Cultural Essays (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2000), 25–41, p. 27.

12. Steven Mosher,

Hegemon: China s Plan to Dominate Asia and the World, 2002, 37.

For updates click homepage here