By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

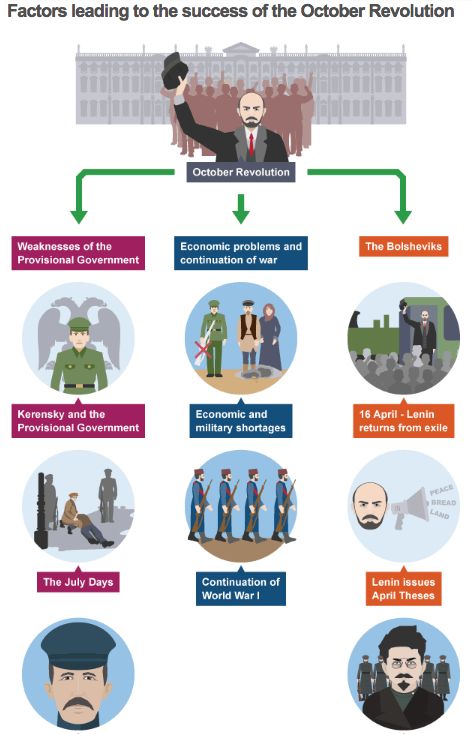

The Russian Empire collapsed with the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II,

and the old regime was replaced by a provisional government during the first

revolution of February 1917 (as pointed out the

older Julian calendar was in use in Russia at the time). In the second

revolution, also termed an "insurrection" that October, the

Provisional Government was removed and replaced. The Bolsheviks promised their supporters 'Peace, Bread, and Power to the

Soviets'. Peace turned out to mean abject capitulation. But was especially

when Kerensky the head of the Provisional Government called for yet another

coalition, that his days were numbered, and the Bolsheviks, who had been

calling for a Soviet Government since February, were the inevitable

beneficiaries. On his return to Russia, Lenin had told his comrades that the

time would come when the Bolsheviks had a majority in the Soviet. Immediately

after the failure of Kornilov’s military coup, the Bolsheviks won that majority.

But the once mighty Russian Empire now also stood at Germany’s mercy.

From the Baltic to the Black Sea, the Russian line had all but disappeared. The

general demobilization Trotsky had announced was not only for rhetorical show.

The Bolsheviks had no money to pay regular soldiers even in Petrograd, where

the garrison still numbered 200,000 men on paper, although few of them were

pretending to be active-duty soldiers. Lenin was struggling to pay Red Guards,

too, for whom the going rate was 20 to 30 kerenki (Kerensky

rubles) per day.

A crude budget report obtained by German intelligence in early February

1918 noted that government expenses for the year were pegged at 28 billion sovznaki, against 5 billion in expected “income.” Simple

math suggested that, whatever currency was used to pay its armed defenders, so

long as the bank strike continued, the days of the Bolshevik regime were

numbered. 1

Its enemies were predictably multiplying in consequence. In the Don

region, Generals Alekseev and Kornilov were assembling a “Volunteer Army” to

fight for the cause of the deposed Constituent Assembly, under the protection

of “Ataman” Kaledin’s Don Cossacks, although Kaledin was unsure of their loyalties. After some friction

over the chain of command, Alekseev agreed to give Kornilov command of the

troops, while handling political, financial, and diplomatic matters himself. By

February 1918, the Volunteers had four thousand men under arms, a force large

enough to focus the Bolsheviks’ attention. The few reliable troops the regime

controlled, a force of some six to seven thousand men under the command of

Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, were sent south to crush

the Volunteers before it was too late. They reached Rostov on February 23, and

Novocherkassk, the Cossack capital, on February 25. Abandoned by the Don

Cossacks, who refused to fight, the outnumbered Volunteer Army fled south in a

soon-legendary “Ice March.” Kaledin, ashamed that his

Cossacks had failed him, committed suicide. The Don Cossacks would elect a new

ataman, General P. N. Krasnov, in May. 2

It was a Pyrrhic victory for the Reds. By sending their best troops

south against the Volunteers, the Bolsheviks had left Russia’s northern and

western flanks unguarded, while forfeiting any real chance of subduing

rebellious Ukraine. In Finland, although a few Red Guards, mostly radical sailors from the Baltic

Fleet, were holding out in Helsinki, an

anti-Bolshevik army commanded by a former tsarist general, Carl Gustav Mannerheim,

already controlled the rest of the country and was threatening Helsinki. In

Ukraine, Kiev had already turned into a multinational battleground, with

French, English, and tsarist Russian officers fighting on behalf of the Rada.

The Bolsheviks, according to a German agent in Stockholm who had spoken to the

senior Bolshevik Lev Kamenev, now “seriously reckoned on a war between Russia

and Ukraine.” In the Arctic port of Archangel, the British Royal Navy had a

squadron offshore, with marines on board, ready to land to protect military

stores sent to Russia before the October Revolution. 3

In Siberia, the strategic picture for Moscow was still bleaker.

Vladivostok, like Archangel, housed huge volumes of imported war matériel,

which had been shipped across the Pacific from the United States. On January

18, 1918, two Japanese warships arrived in Vladivostok to prevent these stores

from falling into hostile hands, whether Bolshevik or German. Quietly, the

Japanese were already shipping weapons and ammunition to the head of the

“Transbaikal Cossack Host,” Grigory Semenov, who

controlled much of northern Manchuria. After hearing an alarming report

that French and British merchants in Irkutsk were being “exterminated” by armed

Bolsheviks and “their property destroyed,” the French government mooted a

proposal for a multinational force (French, British, American, Japanese, and

Chinese) to “proceed from Manchuria to cut the Trans-Siberian Railway.” So far

had Russia fallen that lowly China was now among her oppressors, in a neat

reversal of the humiliating “Eight-Power Expedition” of 1900: China had already

sent more than a thousand troops into Siberia. 4

Would the Germans take the plunge, too? At a crown council on February

13, 1918, Ludendorff proposed a bold offensive into Russia, threatening to

occupy Petrograd if the Bolsheviks refused to sign the draft treaty of

Brest-Litovsk. Paradoxically, he argued that this was the only way to end

things quickly enough in the East to make possible his great spring offensive

on the Western front. Speaking for the Foreign Office, which still retained a

soft spot for the regime it had helped spawn, Richard von Kühlmann

(Appointed foreign secretary in August 1917, he led the delegation that

negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) cautioned against being drawn into the

“center of revolutionary contagion,” and proposed that the Germans revert to

their policy of 1917, standing down on the eastern front so as not to provoke a

patriotic Russian counterrevolution against Lenin. Kühlmann

had a good case, but Kaiser Wilhelm II, incensed that the Bolsheviks had

incited his soldiers to mutiny, sided with Ludendorff.5

Wilhelm II had also been impressed by intelligence reports speaking of

the “madness reigning in Petrograd,” which had become a real concern for the

German high command now that Hoffmann was contemplating occupying the city.

German agents in Petrograd (in particular a reactionary naval officer, Walther

von Kaiserlingk) were telling alarming tales of

assaults on private property across the entire Baltic region. Estonia was of

particular concern because of its huge population of prosperous Baltic Germans,

many of whom were being targeted for “expropriations.” It is notable that two

reports warning of “accelerating terror” were filed by German agents on

February 6, the very day on which Lenin, in a celebrated editorial in Pravda

outlining the Marxist imperative of “expropriating the expropriators,”

encouraged Russian proletarians to rob their better-off neighbors. “The

bourgeoisie,” Lenin wrote, “is concealing its plunder in its coffers … The

masses must seize these plunderers and force them to return the loot [i.e.,

capital accrued through exploiting proletarian labor]. You must carry this

through in all locations. Do not allow [the bourgeoisie] to escape, or the

whole thing will fail… When the Cossack asked if it was true that Bolsheviks

were looters, the old man replied: ‘Yes, we loot the looters.’” 6

In the face of such frightening reports, Kaiser Wilhelm decided that he

had endured enough prevarication. “The Bolsheviks are tigers,” he remarked,

“and must be exterminated in every way.” Although the question of a German

occupation of Petrograd was left unresolved for now, the kaiser made it clear

that he wished to secure at least the “Germanic” Baltic region, to prevent

further Bolshevik horrors there. Ludendorff, for his part, emphasized the need

to seize Ukraine before it was destroyed by Bolshevism. Hoffmann was authorized

to resume the offensive on the eastern front, an offensive unsubtly code-named Faustschlag (literally “fist-punch”) on February 17. The

news was celebrated across Germany, according to a correspondent of Vossische Zeitung, “with school holidays, street

rejoicings, and in some towns with the ringing of bells.” 7

After a cursory aerial reconnaissance of all-but-nonexistent enemy

formations, at dawn on February 18 the German armies marched forward and seized

Dvinsk, which had recently housed Russian Fifth Army

headquarters, and pushed northward into Estonia. In Galicia, the Germans seized

Lutsk the first day and rapidly descended into southwestern Ukraine, en route to the Crimean Peninsula. A Russian-language

proclamation gave a political rationale to the German occupation, denouncing

the Bolshevik dictatorship that “has raised its bloody hand against your best

people, as well as against the Poles, Latvians, and Estonians.” 8

There was little resistance. In the first five days, along a line from

the Baltic to the Carpathians, the Germans advanced 150 miles. At one railway

station, seven German soldiers received the surrender of six hundred Cossacks.

Russia’s commander in chief, the overmatched Ensign Krylenko, observed sadly,

“we have no army. Our demoralized soldiers fly panic-stricken before the German

bayonets, leaving behind them artillery, transport, and ammunition. The

divisions of the Red Guard are swept away like flies.” General Hoffmann wrote

in his diary, with a healthy dose of schadenfreude: “It is the most comical war

I have ever witnessed. We put a handful of infantry men with machine-guns and

one gun on a train and push them off to the next station; they take it, make

prisoners of the Bolsheviks, pick up a few more troops, and go on. This

proceeding has, at any rate, the charm of novelty.” 9

Trotsky had outsmarted himself. To stage his “pedagogical

demonstration,” the Bolsheviks had invited Russia’s enemies to destroy her.

When Krylenko, in a wire to Brest-Litovsk, begged Hoffmann to stop, the German

refused. “The old armistice,” Hoffmann replied, “is dead and cannot be

revived,” although he allowed that the Russians were perfectly free to petition

for a new one. In the meantime, “the war is to go on… for the protection of

Finland, Estonia, Livonia, and the Ukraine.” The Germans promptly captured

Tartu (Dorpat), Reval (Tallinn), Narva, and Lake Peipus. Only after the Germans

had secured Estonia did Hoffmann, on February 23, send revised (much harsher)

peace terms and invite the Bolsheviks to return to Brest-Litovsk to sign them.

10

Lenin summoned the Bolshevik Central Committee on the night of February

23– 24 to discuss Hoffmann’s terms, and his own proposal to accept them.

Trotsky, losing heart, softened his opposition, but could not quite bring

himself to vote for peace. Bukharin, holding firm to his policy of partizanstvo, voted no, along with three other “left

Communist” dissenters. With Trotsky and three others abstaining, Lenin’s

proposal to accept German peace terms needed five votes to pass: he got seven.

He then proceeded to Taurida Palace to put the matter before the Congress of

Soviets, whose approbation on foreign treaties was required according to the

RSFSR statutes written up in January. Against stout opposition, Lenin argued

that Russia had no choice but to “sign this shameful peace in order to save the

world Revolution.” By majority vote (116 to 85, with 26 abstentions), his

motion passed. At 4: 30 a.m. on February 24, 1918, a wire was dispatched to

Berlin explaining that Sovnarkom “finds itself forced to sign the treaty and to

accept the conditions of the Four-Power Delegation at Brest-Litovsk.” The only

remaining problem was who would agree to go to Brest-Litovsk and sign the

humiliating treaty. This dubious honor fell to Grigori Sokolnikov,

People's Commissar of Finance. 11

Still, the Germans marched on, seizing Minsk and Pskov and rolling up

White Russia. On March 1, German troops marched into Kiev, which enabled

Hoffmann to draw up terms with the Rada, arranging for the transfer of

desperately needed Ukrainian grain to Berlin, Vienna, and Constantinople. On

March 2, German warplanes even dropped bombs on Petrograd. Getting the point,

which was hard to miss, on March 3 Sokolnikov signed

the diktat peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk.12

The terms were draconian. In addition to the “full demobilization of the

Russian army,” the Germans insisted that Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland,

the Åland islands in the Baltic, and Ukraine “must

immediately be cleared of Russian troops and Red Guards,” along with, at

Turkish insistence, “the districts of Ardahan, Kars,

and Batum in the Caucasus.” Stripped of sovereign control over these provinces,

Russia lost 1.3 million square miles, one-fourth of the territory of the old

tsarist empire, on which lived 62 million people, or 44 percent of her

population. Estimated economic losses amounted to a third of agricultural

capacity, three quarters of Russian iron and coal production, 9,000 out of

16,000 “industrial undertakings,” and 80 percent of sugar production. Although

Article 9 stated that “no indemnities” would be levied, reparations were hinted

at in Article 8, which spoke of “reimbursement” for the cost of interning

prisoners of war (in that millions more Russians had been captured by Germany

than vice versa). German nationals were granted extraterritorial status inside

Russia, exemption from property nationalizations, and sweeping economic

concessions. In a special insult, the Bolsheviks were required to recognize the

Kiev Rada. Russia’s Black Sea Fleet was ordered to return to its Ukrainian

ports and “be interned there until the conclusion of a general peace or be

disarmed.” 13

Although Sokolnikov had signed the humiliating

Treaty, in political terms Lenin owned it. When Lenin arrived in Taurida Palace

on the night of February 23– 24, Left SR delegates had greeted him with shouts

of “Down with the traitor!” “Judas!” Lenin, unperturbed, had asked his critics

whether they believed that “the path of the proletarian revolution was strewn

with roses.” In the pages of Pravda on March 6, Lenin took a similarly

condescending tone, admonishing Bukharin and the other “Left Communists” to study

military history to learn the value of tactical truces, such as the “Tilsit

Peace” signed by Tsar Alexander I with Napoleon in 1807, which had bought time

for Russia’s ultimate victory. “Let’s cease the blowing of trumpets,” Lenin

concluded, “and get down to serious work.” 14

Earlier in 1917, the Russian Socialist-Revolutionary Party split between

those who supported the Provisional Government, established after the February

Revolution that in the end was led by Kerenski, and those who supported the

Bolsheviks, who favored a communist insurrection. The majority stayed within

the mainstream party but a minority who supported the Bolshevik path became

known as Left Socialist Revolutionaries.

But while the first months of 1918 may be seen in retrospect as an

interlude of relative calm and pluralism in Soviet Russia, contemporaries

understood that civil was upon them. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk caused a

breach between the Bolsheviks and the Left Socialist Revolutionaries (Left SR),

who thereupon left the coalition. In the next months there was a marked drawing

together of two main groups of Russian opponents of Lenin: the non-Bolshevik left like the Mensheviks

and the Right SRs, who had been finally alienated from Lenin by his dissolution

of the Constituent Assembly and the rightist whites.

On March 7, Lenin ordered the evacuation of the government from

Petrograd to the Moscow Kremlin, out of range of German warplanes, where it has

remained to this day. Significantly, Lenin asked the French military mission

for help in arranging logistics. With the Germans bludgeoning Russia into

submission, it made sense to leverage the Entente powers against Germany,

while, that is, Russia still had any leverage. As a show of good faith, on

March 1 Trotsky authorized the landing of Allied troops at Archangel and

Murmansk: five days later, 130 British Royal Marines landed. On March 5,

Trotsky handed a note to Colonel Raymond Robins, the US liaison officer to the

Bolsheviks, asking whether the “Soviet government” could “rely on the support

of the United States of North America … in its struggle against Germany.”

Trotsky also courted Bruce Lockhart, a young Scottish “Russia hand” sent to

Russia as a private envoy by the British cabinet. Although Trotsky was unable

to obtain any concrete promises of military aid (or an Allied pledge to

restrain the Japanese in Siberia), by the time the Brest-Litovsk treaty was

formally ratified on March 14, he had done a great deal to improve relations

with London and Washington. Paris would be a tougher nut to crack because of Lenin’s

decision to announce the repudiation of all Russian state debts on February 10,

1918. In France, owing to massive prewar investments in the tsarist regime,

there were more than a million infuriated Russian bond-holders. Nonetheless,

their very desperation to recover these losses gave the Bolsheviks a certain

back-handed leverage against France. 15

With a wary eye on both the Entente and the Central Powers, Lenin and

Trotsky were quietly rebuilding Russia’s armed forces, jettisoning the

socialist dream of partisan militias for a proper professional army. On January

28, Sovnarkom had created the Red Army of Workers and Peasants (RKKA,

henceforth Red Army) to take the place of the now-demobilized Imperial Army,

with an initial outlay of 20 million rubles. On March 13, Trotsky resigned the

Foreign Ministry and took over as commissar of war. (His successor as foreign

minister, the former Menshevik Georgy Chicherin, came

from an old noble family of diplomats, in another sign of the regime’s grudging

shift toward professionalism.) Significantly, Lenin and Trotsky agreed, against

stout opposition from Krylenko and the Central Committee, to hire ex-tsarist

officers as voenspetsy (military specialists) to

train recruits, a policy formally authorized by Sovnarkom on March 31. In the

course of his negotiations with Lockhart and Robins in March 1918, Trotsky even

requested that British and American officers help train the Red Army, a request

London and Washington approved on April 3, on condition that the Bolsheviks

consent to a Japanese landing in Vladivostok (this condition was enough to kill

the proposal). A new Commissar Bureau was established on April 18, which

instituted the practice, maintained throughout the entire Soviet era, of

assigning political commissars to keep watch over military officers. On May 8,

Lenin and Trotsky even brought back Stavka, now styled the “All-Russian Main

Staff.” In all but its name and the assignment of political commissars, Lenin

and Trotsky had re-created the Russian Imperial Army. 16

Far-sighted though these reforms were, they did little to meet the

immediate threats the regime faced on the Russian periphery. By legally

cordoning off Russia from her former provinces in Finland, Ukraine, and the Transcaucasus, Brest-Litovsk was less “breathing spell”

than incitement to invasion. The Germans landed troops in southern Finland in

early April. Teaming up (during what is dubbed "the Finnish Civil

War") with Carl Mannerheim’s force of “White Finns” advancing from the

north, the Germans conquered Helsinki on April 13, eliminating the last

Bolshevik stronghold in Finland. On the White Russian front, the Germans seized

Mogilev, which had been Russian military headquarters. On the western

borderland of Ukraine, the Romanian speakers of Bessarabia, who had already

declared an independent Moldavian People’s Republic, pledged loyalty to Romania

in April 1918. Although this union would not become official until the postwar

treaties were ratified, Bessarabia was lost to Russia. All the Bolsheviks could

do in retaliation was to seize Romania’s gold reserves, which had foolishly

been shipped to Petrograd in 1916 for safekeeping.

Ukraine was the great prize. By mid-March 1918, even the hapless

Austro-Hungarians had gotten in on the game, seizing Berdichev

in northern Ukraine and then wheeling south to take Odessa with German help. A

southern German army group, led by the formidable General August von Mackensen

(architect of the German breakthrough at Gorlice-Tarnow

in 1915), conquered Nikolaev, home to Russia’s Black Sea dockyards, and

Kherson, before invading the Crimean Peninsula. Rubbing Lenin’s nose in defeat,

Mackensen marched into the great naval base of Sevastopol on May Day 1918. In

eastern Ukraine, a German advance guard, under General Wilhelm Gröner, marched into Kharkov on April 8 and quickly overran

the strategic Donets (Donbass) region, with its abundant coal mines and

factories. By May 8, the Germans had troops as far east as Rostovon-Don

(where they initiated contact with the Don Cossacks and Volunteers) and

Taganrog, with scouting teams sent east to Tsaritsyn (later Stalingrad), on the

Volga. In ten weeks, the German armies had conquered Russian territory larger

than Germany. Twisting the knife, Hoffmann wrote in his diary that “Trotsky’s

theories could not resist facts.” 17

The Germans were not the only ones taking advantage of Russian weakness.

In an astonishing turnabout, considering how close Russia had come to crushing

her ancient Turkish enemy in 1916– 1917, the Ottoman armies thrust forward,

encountering little resistance as they reconquered Trabzon, Erzincan, and then

fortress Erzurum by March 12, obliterating Russia’s hard-won gains from her

1916 victories in a matter of days. By month’s end, the 1914 borders were

restored. On April 4, the Turks marched into Sarıkamış,

erasing the memory of a memorable Ottoman defeat during the first winter of the

war. After rolling up Ardahan province, the Ottoman

commander, Vehip Pasha, took the surrender of Batum

on April 12. On April 25, the First Ottoman Caucasian Army marched unopposed

into Kars. In two months, the Ottoman Empire had turned the clock back

forty-one years in her eternal war with Russia, restoring the 1877 borders. 18

Under cover of the German and Ottoman advances, meanwhile, the Volunteer

Army began to regroup in the north Caucasus. Although, in a blow to the cause,

General Kornilov was killed by a shell on April 13 while bending over a map in

a farmhouse outside Ekaterinodar, the Volunteers

found another commander in General Anton Denikin, another low-born career

soldier in Kornilov’s mold. In early May 1918, just as the Germans were

entering the Don region, the Volunteers returned to Novocherkassk in triumph

and promptly made contact with General Gröner.

Bolshevik-controlled Russia was now pinched between the Ural mountains and the

German armies north, west, and southwest of Moscow and Petrograd, and cut off

by the Volunteers from the coal-producing and industrial areas of Ukraine and

from Baku and the oil-producing Caspian basin.

To counter the invading Central Powers, the Bolsheviks were forced to

swallow their pride and request help from Russia’s “capitalist” wartime allies.

Begging London and Washington to hold off the Japanese at Vladivostok, Trotsky

and Lenin won an early trick: Red Guards duly seized control of the city on

March 24. But the victory was short-lived. On April 4, armed bandits (who may

not have had any connection to the Bolshevik Red Guards) held up a

Japanese-owned shop in the city. Next day, in retaliation, 500 Japanese marines

landed and promptly spread out across the city. The Japanese now had a foothold

in Asiatic Russia, which they would not easily surrender.

Making the situation in Vladivostok more explosive, the Allied consuls

there were eagerly awaiting the arrival of an improvised

legion of nearly fifty thousand Czechoslovak soldiers, most of them former

Habsburg subjects taken prisoner by the Russians on the eastern front. The idea

was that the Czechs would embark at Vladivostok on a roundabout sea journey to

France, where they would reinforce the Allies on the western front. In a gesture

to show good faith with Paris, London, and Washington at a time when the

Central Powers were hammering him hard, Lenin had signed the Czech

laissez-passer on March 15. In retaliation for the Japanese landing at

Vladivostok on April 5, the Bolsheviks ordered the legion, then proceeding

eastward from Penza across the Trans-Siberian, to halt. Under ferocious

pressure from the Allies (especially the French, who had the most to gain if

the Czechs made it to France), the Japanese agreed to withdraw their Marines

from Vladivostok on April 25. For a moment in early May 1918, it seemed that

the Bolsheviks and the Entente might come to terms out of shared antipathy to

the rapacious Central Powers: the Germans were just then carving up the Don

region. 19

Fate then intervened along the Trans-Siberian. On May 14, an episode

occurred at once utterly accidental yet emblematic of the chaos engulfing

Bolshevized Russia in 1918. Even while the Czechoslovak Legion, keen to fight

for the Entente to make a claim for postwar independence, was heading east on

the Trans-Siberian, a detachment of pro-German freed Hungarian prisoners of war

were heading home in the other direction. At a railway siding in Chelyabinsk,

the two trains carrying antagonistic former Habsburg subjects pulled alongside

each other. A quarrel broke out, and a Hungarian hurled a huge piece of scrap

iron (or possibly a crowbar) at a Czechoslovak soldier, hitting him on the head

and killing him. The victim’s Czech comrades lynched the Hungarian and used the

incident as a pretext to take over the railway station, and then, after the

local Soviet protested, the arsenal, and finally the entire town of

Chelyabinsk. 20

Lenin now had reason to regret his decision to allow the Czechoslovaks

to leave Russia with their arms. He had inherited this problem, like so many

others, from Kerensky, who had originally authorized the creation of the legion

to buttress his Galician offensive of June– July 1917 (two divisions had

actually seen action then). At the time Lenin made his decision in mid-March

1918, the interests of the Bolsheviks, Allies, and Czechoslovaks had aligned.

The legion’s troops had been stationed in western Ukraine, in the face of the

Austro-German advance; in a few areas they actually fought the invaders in late

February. In a painful illustration of the state to which Russia had been

reduced, Lenin had agreed to let a heavily armed legion of fifty thousand foreigners

cross Ukraine and south Russia en route for Penza,

just a few steps ahead of the invading armies of the Central Powers. The

Bolsheviks had added the condition, signed by nationalities commissar Stalin on

March 26, that the legion be partially disarmed in Penza, being allowed to

proceed onto the Trans-Siberian with only 168 rifles and a single machine gun

on each train, traveling “not as fighting units but as a group of free

citizens, taking with them a certain quantity of arms for self-defense.” But this

condition proved difficult to enforce, and the Czechoslovaks had predictably

kept most of their weapons. 21

It was the Bolsheviks’ bad luck that, at the time of the Hungarian

provocation in Chelyabinsk, the men of the Czechoslovak Legion were strung out

along the Trans-Siberian railway from Penza to Vladivostok, constituting

everywhere they stood the strongest armed force for miles around. On May 18,

the Legion convened a “Congress of the Czechoslovak Revolutionary Army” in

Cheliabinsk. On May 21, Trotsky ordered the legion disarmed, and had the

members of the Czechoslovak National Council in Moscow, a sort of political

liaison to the legion, arrested. On May 23, the Chelyabinsk Congress, defying

Trotsky, resolved not to disarm. On May 25, Trotsky issued a follow-up order

that amounted to a virtual declaration of war: “All Soviets are hereby

instructed to disarm the Czechoslovaks immediately. Every armed Czechoslovak

found on the railway is to be shot on the spot; every troop train in which even

one armed man is found shall be unloaded, and its soldiers shall be interned in

a war prisoners’ camp.”

If war is what Trotsky wanted, war is what he got. But the order of

battle did not favor him. By May 25, the Legion, under the command of a

self-styled “general” named Rudolf Gajda, had already seized control of the

railway and telegraph stations at Mariinsky and Novonikolaevsk

(Novosibirsk), severing Moscow’s connections with eastern Siberia. On May 28,

the Czechs took Penza. Tomsk fell on June 4, and Omsk on June 7. On June 8,

eight thousand Czechoslovak soldiers captured the regional capital of Samara, as

one of them later recalled, “in the same way that one grabs hay with a

pitchfork.” In early July, Ufa fell. On July 11, the Czechs wrenched control of

Irkutsk from Austro-German prisoners of war who made up the local Red Guard.

With an advance guard having already seized Vladivostok, the Trans-Siberian

Railway, from Penza to the Pacific, was now in Czechoslovak hands. 22

Under cover of the Czech advance, Russia’s

beleaguered liberals and non-Bolshevik socialists mounted a comeback. In

Omsk, a committee proclaimed the “Government of Western Siberia” on June 1. In

Samara, deputies who had fled Petrograd after the Bolsheviks dissolved

parliament in January formed a “Committee of the Constituent Assembly” (Komuch) devoted to restoring its authority. To cultivate

Entente support, Komuch abrogated the Brest-Litovsk

treaty and promised to honor the Russian state debts Lenin had annulled. While

its authority did not yet extend beyond Samara, Komuch

had laid down an important marker, as the cause of the deposed Constituent

Assembly was one that millions of Russians, including the men of Denikin’s

Volunteer Army, could rally around. 23

Komuch's People's Army grew from a

dense web of underground officer groups that had existed since early 1918 in

the Volga Military District, as the new and febrile Soviet authorities

struggled to assert control of these peripheral (and, in terms of the Constituent

Assembly elections in 1917, solidly SR) provinces. With the revolt of the

Czechoslovak Legion, these anti-Bolshevik cells emerged, in early June 1918,

under the command of Colonel N.A. Galkin (supported by a staff led by the SR

Colonel VI. Lebedev and Komuch member B.B. Fortunarov). Following negotiations with Major Stanislav Cecek, commander of the Legion's 1st Division, a joint

Czech-Komuch Volga Front was soon established,

centered on Samara, which, in a series of lightening

operations, succeeded in driving Red forces from the important regional centers.

By July 1918, Russia had been reduced to a shadow of its former self.

Siberia’s cities were ruled by Czechs and Slovaks, its hinterland by Siberian

Cossacks. Semenov’s Trans alone. The Don region was controlled by Don Cossacks,

the North Caucasus by Kuban Cossacks and Volunteers, while the Transcaucasus was being carved up by Turks. A German

expeditionary force was in Georgia. Far from escaping the world war, Lenin’s

peace policy had turned Russia into the playground of outside powers (which as

we shall see next acted almost as chaotic as the Russian Civil War

participants).

The Triple Entente, which, with the United States, won the Great War,

did not act as an ideal coalition. As a result, the Allies never developed a

single concerted policy on Russia. This led to there being no common goal or

‘mission’ for Russia that was accepted by all participants, which left

individual commanders to develop strategies to fit local conditions. In some

regions, this led to an unintended expansion of the operation and in others no

set goal to work towards. No one member of the alliance had such overwhelming

power in 1919 that it could dominate the relationship. Nor was it the norm to

have an alliance of such strong equals that no single nation could control the

policies and overall operation of the War.

Rapidly changing events in highly fluid situations plagued all players.

Even if all the leading actors in the intervention had been equally prescient,

they were all cursed by poor, wrong or non-existent information, often filtered

through particular personalities, individual self-interests and transmitted by

feeble and slow communication systems. Unified strategic decisions were nearly

impossible. Political and military leaders of all the Great Powers were forced

to deal with constant turmoil. Most dealt with it reactively, scrambling to

find answers and take actions to slow or stem its effects. All tried to use it

or to shape matters to their own ends. In turn, such political leaders'

decisions shaped their nations' strategic perceptions and aims.

Nations working together have their own national interests. Each has its

own strategic goals and, when there is resistance from allies, each goes its

own way, usually secretly. Equally, each country may endeavor to change or

pressure other allies to go along with them. Moreover, when individual national

interests clash with the collective alliance goals, some will try to promote

what they consider to be the only correct solution. Self-perceptions of power

also play a role. Senior and junior allies may operate differently and for

different reasons. The Great Powers, in trying to re-establish the Eastern

Front in Russia in 1918, illustrated many of these things. A case-in-point was

the United States, which first tried to prevent any Allied military intervention,

and then, when that became inevitable, refused to cooperate with its Allies in

Siberia and attempted to restrict US troop employment in North Russia. At a

more strategic level, the US administration agreed to have Japan in overall

command in Siberia but then neglected to direct its commander to submit to

Japanese leadership.

Other Allies fared no better. Japan looked at intervention as a means to

control Siberia for its own national purposes. It agreed to intervention

originally and ostensibly to assist the Czech Legion to escape Siberia but

refused to send troops west of Lake Baikal to fight the Bolsheviks who were

trying to prevent the Legion's exit. Also, the Japanese actively supported

rebels against the established anti-Bolshevik government of Admiral Kolchak,

rendering impossible the avowed purpose of the operation. Japan consented to

limit its troop strength to that of the US contingent but immediately sent

double that number to dominate the Russian Maritime Provinces. This action

alone spawned a heightened US distrust of its Asian Ally's intentions. Japan

wished to control Siberia to counter the historical and ongoing US economic

incursions into China. America's support of the ‘open door’ trade policy in

China directly conflicted with Japan's wish to monopolize trade in its sphere

of influence. This rivalry prevented the two nations from working together to

establish a stable anti-Bolshevik government in Siberia, something Japan could

not permit if it were to obtain the dominance it desired. But Japan was not the

unified nation it appeared to be. The governing elite was divided over its

approach to both Russia and the United States. Although the Army appeared to be

in charge in Siberian operations, Prime Minister Terauchi and others were at

odds with the General Staff and were able to resist enlarging Japanese military

forces in Siberia late in 1919. There were conflicts in the Japanese government

on how to work with the United States, but there was no consensus other than to

allow the military to continue its operations in Russia. This was only one part

of the chaotic nature of the Allied intervention.

Because of their ignorance of Bolshevik methods and goals, the United

States saw the two Russian factions as equals in the struggle, but they viewed

the anti-Bolsheviks as reactionaries ready to return to the tyrannical

government of the Tsars. For this reason, the United States would not support

Kolchak against the rebels in Siberia. National interests submerged the

collective Allied goal. In Britain's case, it not only worked for its own

interests, but it also clashed with the interests of parts of its own Empire.

In its turn, France undermined the White Russian General Denikin in

favor of the Ukrainian rebels, despite the agreed Allied aim. In addition,

France assiduously worked at advancing any scheme that would ensure Russian

payment of the enormous pre-war loans and massive war debts. This blinkered

view of pursuing compensation by any means to the detriment of common goals

steadily undermined collective Allied efforts to assist the Whites. These

illustrate how national self-interest trumped many of the collective goals.

But the Alliance's strategic aims in Russia were also fluid. The Great

War was the driving force until November 1918. Up to then, the Allies'

intentions in Russia were to re-establish the Eastern Front to alleviate German

pressure on the Western Front. The United States, however, did not accept this

goal as achievable or necessary. But with the Armistice, even this goal was no

longer relevant and the war on Bolshevism became one of many other reasons for

intervention. Yet the Allies could not agree on one policy as it applied to

Russia. Moreover, with the end of fighting in Europe, Russia lost strategic

importance to the need to produce a peace treaty in Paris.

Significantly, Russia was intimately tied to the laborious and often

bitter negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference. Even well after the

Armistice, Allied soldiers were part of the continued fighting and turmoil

across Russia. At Paris and in Allied capitals, there was fear that Russia

could fall under the influence of Germany, despite the latter's defeat in

Western Europe. Russia could not be separated from the larger subject of

Germany and its place in Europe. Revolution and tumult were spreading in Middle

and Eastern Europe and in Germany. So, while the negotiating Great Powers did

not want Russia present at the Paris Conference, that nation could not be

separated from their talks and decisions. Here was a major weakness of the

Allied interventionist effort: without Russia in Paris, the Allied intervention

was likely doomed to be piecemeal, and driven by individual self-interest. And

Russia also had an impact on nations far from its shores.

There were smaller actions and other motives at play in these events,

and mistrust often spread. In Canada, Sir Robert Borden at first urged his

government to establish economic missions to accompany the Canadian contingent

destined for Siberia, hoping to reap economic rewards. Based on the way Britain

had acted during the Great War with respect to munitions orders, directing them

to the United States and ignoring Canada's factories, he did not trust the

British economic delegation to look after Canadian interests. For some

Canadians in 1919, Russia offered an opportunity to help recoup the financial

cost of the Great War and also keep the newfound Canadian industrial success

going well into the 1920s. So Canada, like other nations, mixed too many

expectations on a policy that should have been kept as simple as possible,

given war's natural characteristic to be chaotic and uncontrollable.

Personalities had a major influence on the courses that nations

followed. Individuals can often drive action or cause inaction. Politics and

personalities cannot be ignored. Decisions, in turn, determine what will not be

done as well as what is done. And people made these decisions. Strong-willed

people are very important in a functioning alliance. In the Allied intervention

in Russia, there were influential people at every level of decision-making. The

strongest examples both in the actual events and in historical interpretation

were David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, and Woodrow Wilson.

Although some American historians point their finger at Wilson for

singlehandedly causing the failure of the Allied Intervention, more honestly it

has to be laid at the feet of more than him. There were many others who had

various shares in the cause of this failure, but besides Woodrow Wilson,

another major contributor was British Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

George Kennan's conclusion - blaming Wilson for the outcome - is based

more on American national centrism rather than detailed analysis: that is,

Wilson was against both Russian factions equally because neither lived up to

his idealistic version of the American dream. Initially, Wilson had fought

against sending Allied troops into Russia from a sense of superiority combined

with naïveté. He firmly believed that the Russian Revolution was based on a

desire of a people to rid themselves of a tyrannical government and to

establish democracy. Convinced to the point of unreason, he considered it

immoral to interfere in the internal political struggles of the Russian people.

The United States had to set an example to other nations, and therefore should

not actively interfere on one side or the other of an internal political fight.

Yet Wilson's view was, ironically, also anti-Bolshevik, although not to the

point that he would allow the US military to assist either faction in Russia.

He also deeply abhorred imperialism, and therefore he was suspicious and

reluctant to act with an entity he naturally recoiled from, such as the British

Empire or a reconstituted Russian one. He hoped to use the United States'

strength to create a new international order free of war or revolution. It was

one in which the United States would be the pre-eminent political and economic

power.

Having the United States participate in what the president saw as an

immoral undertaking would undermine that nation's image as a ‘shining city on a

hill’. Wilson firmly believed that the United States was divinely destined to

lead the world to an orderly, liberal and capitalist international society.

Wilson's self-assurance in his own intellect, coupled with a belief in his own

moral superiority, made him impervious to differing rational argument. Wilson

didn't recognize his own intellectual limits or corrected his mistakes in

Siberia. In one author's view, he had the mind of a country schoolmaster and

the soul of an army mule. Wilson interpreted the First World War as a crusade

to make the world safe for democracy but first viewed that conflict as caused

by trade rivalries, which the United States was supposedly above. Yet the US

president was averse to intervening in Siberia because of trade disagreements

with Japan. Moreover, his antipathy towards the military intervention ensured

that US troops involved would be inadequate for the purpose.

He was not alone. While Wilson was central to slowing down US

participation in the intervention, Lloyd George almost single-handedly

prevented the British from supporting the Whites effectively. Unlike Wilson,

the British prime minister was the consummate politician who understood the

need to keep his electorate happy while maintaining British prestige and

pre-eminence internationally. Like Wilson, Lloyd George was a bit naive about

Bolshevism, seeing it solely as a Russian problem. He did not understand Lenin's

avowed goal of worldwide revolution. However, he did understand the danger to

domestic peace and the desire of Great Britain's war-weary populace to return

quickly to a normal, peaceful regime. British Labour's

opposition to military intervention could have, in Lloyd George's mind,

endangering the whole domestic political system and Britain's domestic

tranquility. Lloyd George knew that Britain could not afford nor would

undertake another major war, especially in Russia where the Bolshevik

revolution at first seemed to dispose of a dictator and replace him with a

popular government.

But early in the intervention debate, the British prime minister was supportive

of military involvement when it appeared to be a way of easing pressure on the

Western Front by re-establishing an Eastern Front. His acceptance increased

dramatically in the spring of 1918 when it looked like the Germans' Michael

Offensive would crush the Allies. And so Lloyd George accepted sending Allied

troops to guard military stores at both Archangel and Vladivostok to prevent

their capture by Germany. However, he became skeptical of intervention once the

Armistice was achieved in November 1918. From then, he actively opposed the

scheme in both the British Cabinet and at the Paris Peace Conference. Lloyd

George remained fully sensitive to the manpower limitations of the British Army

as well as the unaffordable costs any intervention would entail. As the head of

a coalition government dominated by Conservatives, but with strong willed

Liberals as well, Lloyd George could not afford a single political failure that

could be laid at his feet personally. Fully aware of this, he governed accordingly.

Ever the pragmatist, Lloyd George's greatest fear was unrest among the

British population. Military intervention in Russia, in the view of the Labour Party and articulated by the Trades Union Congress,

was cause for a General Strike. For this reason, Lloyd George could not risk

openly supporting a full-scale intervention against the Bolsheviks. He

maintained this stance despite overt pressure from Winston Churchill, the one

man who consistently pushed for a military solution to the Russian problem. To

add to the chaotic nature of British politics was the problem that Lloyd George

never quite said "no" and never quite said "yes" perhaps to

cause a delay in making any decision, thereby gaining time. But whatever the

case, such overt inaction meant that ‘others’ like Churchill took action and

were difficult to control. Nonetheless, it was British Prime Minister Lloyd

George's actions and inactions that prevented adequate British support for the

anti-Bolsheviks and together with President Wilson ensured the failure of the

intervention.

Failure, of course, was also due to purely Russian issues and the Allied

leader's ignorance of Bolshevik goals. Lenin was a master at chaotic diplomacy.

For instance, he kept the American Red Cross representative Robins and the

United States convinced curing the Brest-Litovsk negotiations that he would

accept Allied help against the Central Powers. This allowed the Bolsheviks to

retain power in Moscow. He employed similar methods against Trotsky and other

Bolshevik leaders to bolster his personal power. He used diplomatic confusion

to gain time against German negotiations to delay or stop them from a

resumption of fighting. And he was willing to cede Russian territory to ensure

the Bolsheviks retained power in Russia, convinced that world revolution would eventually

return all that was lost.

Even before Lenin attained power, other Russians made decisions that

ensured the Bolshevik triumph. Without the lies and machinations of Vladimir N.

Lvov, it is possible that Kerensky and General Kornilov would not have had

their violent falling-out. If Kerensky and Kornilov had not become open rivals,

it is possible that the Bolshevik revolution would have failed. And it was

personal distrust, inflated egos and lies that caused the Kornilov-Kerensky

schism.

Other White leaders also shared similar failings given their widely

divergent political views and egocentric personalities. When coupled with their

personal ambition and frequent infighting, it also led to turmoil and the final

Red success. Denikin, a believer in a Great Imperial Russia, refused to ally

with the Ukraine Nationalist Petlyura to fight the

Bolsheviks in South Russia. In the Baltic, Yudenitch

was an arrogant reactionary who alienated regional allies vital to his access.

Consequently, they denied him support necessary for victory. In North Russia, Chaikovsky feared his own military leaders, continuously

quarreled with Allied military commanders over political power and failed to

persuade the people in North Russia to support him. Finally, Admiral Kolchak

could not control his own forces and lost the confidence of the Czech Legion,

the one capable military force on his side in Siberia. He also alienated the

local population whose support he needed. Also, the Japanese-backed his Cossack

opponents ensuring the White forces were divided.

Coupled with the incompetence of the White Russian leadership was the

individual actions of Allied personnel on the spot in Russia. Whether it was

L-S General Graves in Siberia refusing to cooperate with the Japanese Allied

Commander-in-Chief Otani or British diplomatic representative Bruce Lockhart in

Moscow striving to prevent Japanese intervention against the wishes of his own

government, individuals enhanced the diplomatic uncertainty by their actions.

Ironside and Maynard in North Russia worked from a necessity to maintain a

strong force and defeat the Reds, and in the case of Ironside link the North

Russia army with Kolchak's Siberian army while being bombarded with

contradictory orders from Churchill and Lloyd George over the Allied

withdrawal. Both strove for offensive victory while trying to plan the

evacuation of all Allies from North Russia. General Sir W. R. Marshall, in

Mesopotamia, interfered with General Dunsterville's

Caucasus intervention by first trying to divert Dunsterforce

to face the Turks in Mesopotamia and then delaying the necessary support for Dunsterville in Baku until it was too late. General Gough

over-stepped his authority by bullying Yudenitch into

creating another White Russian Government for North Western Russia and

recognizing Estonian independence, which added to the diplomatic chaos in

London and Paris. And General Knox wholeheartedly supported Admiral Kolchak up

to the latter's ignominious rout from Omsk despite the blatant incompetence of

the Russian military in the fight against the Reds and the complete inability

of the White administration to govern the Siberian region. These individuals,

while not the cause of the chaos, helped perpetuate and enhance it.

Complicating this were the vast distances between combat areas in

Russia.

This mixture of internal divisions and space prevented concentrated

Allied military aid. Providing needed materiel to these diverse and distant

areas was exacerbated by the Allies' chronic logistics and communications

problem -lack of sufficient shipping, a single railway and the impediments of

troops and politicians who had no desire to fight so far from home.

The revolutions in Russia caused international turmoil. No one knew

where events were leading or what would occur next. Utter confusion reigned.

From the end of 1917, events often forced governments and leaders to react even

though they lacked both the time and the information to develop a comprehensive

strategy. The various events in Russia stretched the already inadequate Allied

resources beyond effective utility and created the illusion that they were

separate and independent. In reality, they all impacted politically and

militarily on each other.

1. German military intelligence report filed in Berlin, January 9/ 22,

1918, in Bundesarchiv Militärabteilung

(German Military Archives). Freiburg, Germany (henceforth BA/MA), RM 5/ 4065;

and Lindley report to Arthur Balfour, sent from Petrograd, February 8, 1918, in

National Archives of the United Kingdom. Kew Gardens, London, UK, Public Record

Office (henceforth PRO), FO 371/ 3294.

2. Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, 1919-24,1994, 15–

23.

3. German military intelligence reports filed in Berlin, January 22,

February 2, and February 12, 1918, in BA/ MA, RM 5/ 4065. Kamenev: German

agent’s report from Stockholm, February 18, 1918, in BA/ MA, RM 5/ 4065.

4.H. Ullman, The Anglo-Soviet Accord, vol. 1, 89– 92.

5. Citations

in Winfried Baumgart, Deutsche Ostpolitik, 1966, 23– 25.

6. V. I. Lenin's

Sochineniia,1958, vol. 22, 231. German intelligence reports: agent report from

Petrograd, February 1, 1918, and two from February 6, 1918, in BA/ MA, RM 5/

4065.

7. Cited in John W. Wheeler-Bennett, Brest-Litovsk the Forgotten Peace,

March 1918, 232. “Bolsheviks are tigers”: cited in Richard Pipes, Russian

Revolution,1991, 586.

8. Cited in Bunyan and Fisher, The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917-1918;

Documents and Materials, by James Bunyan and H. H. Fisher,1961, 512.

9. Citations in Wheeler-Bennett, Forgotten Peace, 245, 258– 259.

10. Cited in ibid., 246.

11. Ibid., 258– 259; Bunyan and Fisher, Bolshevik Revolution 1917– 1918,

519– 520. Voting with Lenin were Stalin, Zinoviev, Sokolnikov,

I. T. Smilga, Y. M. Sverdlov, and Elena Stasov, with

Bukharin, A. S. Bubnov, A. Lomov, and Moisei Uritsky against. Abstaining were

Trotsky, Joffe, Felix Dzerzhinsky and Nikolai Krestinsky.

Kamenev was in Stockholm, en route to London on a

diplomatic mission.

12. Baumgart, Deutsche Ostpolitik, 119– 127.

13. The text of the treaty is reproduced, in English translation, in

Wheeler-Bennett, Forgotten Peace, 403– 408. For more on economic concessions,

see Pipes, Russian Revolution, 595.

14. Citations in Wheeler-Bennett, Forgotten Peace, 260, 279.

15. Citations in Ullman, Anglo-Soviet Accord, vol. 1, 124– 125; and (for

Robins) Pipes, Russian Revolution, 597– 598. The decree of “Annulment of

Russian State Loans,” February 10, 1918, is reproduced in Bunyan and Fisher,

Bolshevik Revolution 1917– 1918, 602.

16. The founding decree of the Red Army, and the appropriation of 20

million paper rubles, is preserved in Rossiiskii

Gosudarstvennyi Voennyi Arkhiv (Russian Government

Military Archive). Moscow, Russia (henceforth RGVA), fond 1, opis 1 (“Kantselariya”). For

other key dates, see Jacob W. Kipp, “Lenin and Clausewitz: The Militarization

of Marxism, 1914– 21,” Military Affairs 49, no. 4 (October 1985): 188.

17. Baumgart, Deutsche Ostpolitik, 119– 127. On Romania, see Mugur

Isarescu, Cristian Paunescu, and Marian Stefan, Tezaurul

Bancii Nationale a Romaniei la Moscova—

Documente. 18.

“Augenblicklichen Lage im Kaukasus,” April 6, 1918, in BA/ MA, RM 40/ 215; and

Joseph Pomiankowski, Zusammenbruch des Ottomanischen

Reiches Erinnerungen an die Türkei aus derZeit des

Weltkrieges.1969, 335.

19. Ullman, Anglo-Soviet Accord, vol. 1, 146– 151.

20. Serge P. Petroff, Remembering a Forgotten War, 1– 2.

21. Stalin to Czechoslovak National Council, March 26, 1918; reproduced

in Bunyan, Intervention, 81 and passim.

22. Pipes, Russian Revolution, 631– 632; Petroff, Remembering a

Forgotten War, 2000, 9.

23. On the formation of Komuch, see Scott B.

Smith, Captives of Revolution (2013).

For

update click homepage here