The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its

consequences in Russia Part Seven

Description of

persons involved.

As we have seen, the

British government formulated its Russian policy in the Cabinet’s discussions

in early December 1917. It was decided to support ‘any responsible body in

Russia willing to oppose the Maximalist movement (i.e. the Bolsheviks)’, and

‘within reason to give money freely to such bodies as were prepared to help the

Allied cause’.

In the meantime, the

French government had started its own operations in Russia mainly to support

the Romanian Army that was being pushed towards Ukraine by the German and

Austrian armies. To coordinate the present Allied policy a secret Anglo-French

conference was called in Paris. The Conference was concluded with the

‘Anglo-French Convention’(Convention entre la France et l’Angleterre

au sujet de Faction dans la Russie méridionale) on 23 December 1917, in which southern Russia was divided into ‘spheres of

activity’ between the British and the French. London and the French really

operated on their zone according to this ‘international’ agreement and British

intelligence officers, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Keyes, began to execute the

War Cabinet’s instructions in Petrograd. They worked out, in co-operation with

the Russian banker Karol Yaroshinsky, an elaborate

scheme to finance the anti-Bolshevik forces

within the British ‘sphere of activity’. It was designed to counteract the

influence of German finance within Russia by bringing Russian banks under

British control. Under the scheme, the British government was to give Yaroshinsky a loan of six million pounds (200 million roubles) to purchase a majority of securities in five

Russian banks. Yaroshinsky was also supposed to set

up ‘a Cossack Bank’ in South Russia, which could issue banknotes, and thus

provides funding to the Don Cossacks and the Volunteer Army. The wild plan

proceeded, after the approval of the Cabinet’s Russian Committee, and

initially, 185,000 pounds were credited to the bank account of British agent

Hugh Leech, from where the sum was drafted by Yaroshinsky’s

agents.

Keyes was certainly

thinking on a grand scale when he wrote:

We have the right to

nominate our own directors and these banks with their 300 odd branches and

their interests in numerous commercial and industrial! concerns offer us an unrivaled commercial intelligence system for

investigating old and new undertakings. They offer us the means of setting on

their feet such as our concerns as having suffered during the disorders, and of

handing out loans and other financial interests.

When Wilson, on

December 26, agreed to secretly advance the French and British whatever funds

might be “necessary” to finance the Cossack coup against Lenin. The Allied PMs

in Paris then sent French and British military scouts to the Don to see what

the Cossack program looked like.

In this context,

Paris had approved a credit of 100 million rubles to restore order in Russia

and get the country back in the war against the Central Powers, that is, to

mount a coup against the Bolsheviks.

America’s spymaster

DeWitt Clinton Poole, as was reported to the Secretary of State, wrote that

“clandestine preparations” were being made for “counter-Bolshevik outbreaks” in

Moscow and other cities, confirming that a Plot was afoot in December 1917. And

on 18 January 1918 wrote to the Department of State on18 January 1918, that

there was an “urgent” need for cash “at once,”

200 million rubles.

Described in part one, two,

three, and four, five,

and six, it remains the most audacious spy

plot in British and American history, a bold and extremely dangerous operation

to invade Russia, defeat the Red Army, and mount a coup in Moscow against

Soviet dictator Vladimir Ilich Lenin. After that, leaders in Washington, Paris,

and London aimed to install their own Allied-friendly dictator in Moscow as a

means to get Russia back into the war effort against Germany. Along with the

British and the French, the plot we now know had the “entire approval” of

President Woodrow Wilson. As he ordered a military invasion of Russia, he gave

the American ambassador, the U.S. Consul General in Moscow, and other State

Department operatives a free hand to pursue their covert action against Lenin.

The result was thousands of deaths, both military and civilian, on both sides.

On Wednesday, 28

August, Eduard Berzin (captain in the

Latvian Rifle Brigade) took the train to Petrograd, as we have seen. Sidney

Reilly followed the next night. On Friday, the 30th, Reilly had the meetings (in the street and

his flat) with Berzin, whom perhaps he no longer trusted. According to his best

biographer, he met sometime that day with Captain Cromie as well. So may have

Berzin, separately.1

What we know is that

head of the Cheka Felix Dzerzhinsky had chosen Alexander Engel’gardt

(descended from a prominent Latvian family)

to lead the three-man team of Chekists sent to penetrate Cromie’s

organization in Petrograd. Engel’gardt took the alias

“Shtegel’man.” The latter together with Jan Sprogis posing as “Shmidken,”

along with Buikis (“Bredis”)

took part in the Cheka operation directed by Dzerzhinsky and Dzerzhinsky’s

second-in-command Jacov Peters the latter who took

over briefly when Dzerzhinsky stepped back in the summer of 1918 and hence

Peters took a primary role in designing the counter-plot to defeat Lockhart and

some of the co-conspirators.

Buikis

(“Bredis”) and Engel’gardt

(“Shtegel’man”) penetrated Captain Cromie’s

counter-revolutionary organization in Petrograd. He and Captain Eduard Berzin

then approached Lockhart in Moscow and encouraged him to believe they could

deliver the Latvians to his plot. Buikis (“Bredis”) and Engel’gardt (“Shtegel’man”) and a fellow Cheka agent, Lieutenant Sabir,

were present at the British embassy building in Petrograd when Cromie met his

death there.

It was, in fact,

Cromie who had triggered the Plot about three weeks earlier when he sent Engel’gardt/Shtegel’man and Sprogis/Shmidkhen with a note for

the British agent in Moscow. Dzerzhinsky and Peters, however, needed Engel’gardt and Alexander Shtegel’man

in the former capital, where he could take advantage of his connection with

Cromie to further penetrate the counter-revolutionary movement there. They sent

him back and chose A century later, it is impossible to say what were the

details of the Petrograd conspiracy whose principals meant to keep it secret,

except that Cromie’s “plans may have included the destruction of certain

bridges,”2 that he was “interested in several [Petrograd counter-revolutionary]

organizations,” “that considerable sums of money were being spent,”3 and that

some of the money probably supported counter-revolutionary agitation in the

First Division of the Red Army stationed in the former capital.4 Cromie, who

had been funneling Whites to Archangel to assist General Poole’s march south, also promised

to supply him with armored craft for rivers and lakes.

From now on, the

plotters would find themselves in increasingly dire straits. Much of that came

from their own faulty security measures:

—Captain Cromie did

not properly vet Jan Shmidkhen before sending him on

to recruit Latvian Colonel Berzin for the Allied coup. Berzin reported the

approach to the Cheka.

—Reilly wrote the

address of his Moscow safe house on that card that Berzin found in Sidney’s

Petrograd safe house. Berzin gave the address to the Cheka.

—Lockhart wrote and

signed a pass for a Latvian courier who was going to meet with Allied forces at

Archangel. The message didn’t go north. It ended up with the Cheka.

—Reilly gave cash to

Berzin, not knowing he was an agent provocateur sent by the Cheka. Berzin

turned the money into the Cheka.

—The Allies failed to

check Marchand’s bona fides, allowing him to witness the secret meeting in

Poole’s office and write an account for Dzerzhinsky and Lenin. With all that

evidence in hand, Dzerzhinsky and Jacob Peters soon would ensue with Western

agents' roll-up in Russia.

Jacob Peters

considered the Americans the “worst compromised” in the Lenin Plot, and if

DeWitt Poole could be captured, that would cement the Cheka’s case against the

Yanks.5

Poole knew he had to

get out fast. He sent a message to Chicherin’s

assistant, Karakhan, asking for a pass to leave

Russia. He promised to return the favor someday.

Karakhan responded quickly with travel papers. Evidently, the

Soviet foreign commissariat didn’t want complications like American diplomats

getting shot by the Cheka. Better to help Poole get out of the country as

quietly as possible.

Sidney Reilly got out

of Russia using a passport in the name of Georg Bergmann, a fictitious merchant

in Riga. One of the boots (forgeries) the British embassy kept on hand for

smuggling people out. George Hill gave it to him. Hill got out, too, but lost

fourteen of his agents in the process.

Peters told Lockhart

when he was in jail that the Americans were the worst compromised in the Allied

plot against Lenin. It was a reference, of course, to Kalamatiano

and Poole. But Peters said that for “political reasons,” the Soviets were not

implicating the Americans as much as the French and British.6 Those “political

reasons” apparently were the Soviets’ desperate need for U.S. foreign aid.

It must have seemed like

a good idea at the time: Overthrow Lenin and the Soviet government on

humanitarian, military, and economic grounds and install a benevolent dictator

in Moscow until a democratic government could be elected. But it failed. It

failed because it was a tragedy in the classical sense—flawed from the very

beginning. And those tragic flaws brought on the Lenin Plot’s own destruction.

After it was over, not much had changed in Russia except that many people were

dead and a lot of money had been wasted. Lenin was still in power, and Soviet

methods would only get more extreme in the decades to come.

The main flaw on the

political side of the Lenin Plot appears to have been slipshod security on the

conspirators' part. Agents were not properly vetted. Some seemed to have been

accepted solely because they were fast talkers. That laid the plot open to infiltration

by the Cheka.

But even if the

Allied coup in Moscow had succeeded, how long could the Western powers have

held Russia? The country might have risen in a new revolution against the

Western occupiers. Russia is a big place. Nailing down power, there would have

required an Allied force as big as the one on the western front in France.

Whereby given the many players that by now became involved in the allied

intervention (including nations that did not know the secretive (because it

involved individual agents), American and British plot can be said to have

become rather complex.

The Triple Entente,

which, with the United States, won the First World War, did not act as an ideal

coalition. As a result, the Allies never developed a single concerted policy on

Russia. This led to no common goal or ‘mission’ for Russia that was accepted by

all participants, which left individual commanders to develop strategies to fit

local conditions. In some regions, this led to an unintended expansion of the

operation and, in others, no set goal to work towards. No one member of the

alliance had such overwhelming power in 1919 that it could dominate the

relationship. Nor was it the norm to have an alliance of such strong equals

that no single nation could control the War's policies and overall operation.

Rapidly changing

events in highly fluid situations plagued all players. Even if all the leading

actors in the intervention had been equally prescient, they were all cursed by

poor, wrong, or non-existent information, often filtered through particular personalities,

individual self-interests, and transmitted by feeble and slow communication

systems. Unified strategic decisions were nearly impossible. Political and

military leaders of all the Great Powers were forced to deal with constant

turmoil. Most dealt with it reactively, scrambling to find answers and take

actions to slow or stem its effects. All tried to use it or to shape matters to

their own ends. In turn, such political leaders' decisions shaped their

nations' strategic perceptions and aims.

Nations working

together have their own national interests. Each has its own strategic goals

and, when there is resistance from allies, each goes its own way, usually

secretly. Equally, each country may endeavor to change or pressure other allies

to go along with them. Moreover, when individual national interests clash with

the collective alliance goals, some will promote what they consider to be the

only correct solution. Self-perceptions of power also play a role. Senior and

junior allies may operate differently and for different reasons. In trying to

re-establish the Eastern Front in Russia in 1918, the Great Powers illustrated

many of these things. A case-in-point was the United States, which first tried

to prevent any Allied military intervention. When that became inevitable, it

refused to cooperate with its Allies in Siberia and attempted to restrict US

troop employment in North Russia. At a more strategic level, the US

administration agreed to have Japan in overall command in Siberia but then

neglected to direct its commander to submit to Japanese leadership.

Other Allies fared no

better. Japan looked at intervention as a means to control Siberia for its own

national purposes. It agreed to intervention originally and ostensibly to

assist the Czech Legion to escape Siberia. Still, it refused to send troops west

of Lake Baikal to fight the Bolsheviks, trying to prevent the Legion's exit.

The Japanese also actively supported rebels against the established

anti-Bolshevik government of Admiral Kolchak, rendering impossible the avowed

purpose of the operation. Japan consented to limit its troop strength to that

of the US contingent but immediately sent double that number to dominate the

Russian Maritime Provinces. This action alone spawned a heightened US distrust

of its Asian Ally's intentions. Japan wished to control Siberia to counter the

historical and ongoing US economic incursions into China. America's support of

the ‘open door’ trade policy in China directly conflicted with Japan's wish to

monopolize trade in its sphere of influence. This rivalry prevented the two

nations from working together to establish a stable anti-Bolshevik government

in Siberia, something Japan could not permit if it were to obtain the dominance

it desired. But Japan was not the unified nation it appeared to be. The

governing elite was divided over its approach to both Russia and the United

States. Although the Army appeared to be in charge of Siberian operations,

Prime Minister Terauchi and others were at odds with the General Staff. They

were able to resist enlarging Japanese military forces in Siberia late in 1919.

There were conflicts in the Japanese government on how to work with the United

States. Still, there was no consensus other than to allow the military to

continue its operations in Russia. This was only one part of the chaotic nature

of the Allied intervention.

Because of their

ignorance of Bolshevik methods and goals, the United States saw the two Russian

factions as equals in the struggle. Still, they viewed the anti-Bolsheviks as

reactionaries ready to return to the tyrannical government of the Tsars. For this

reason, the United States would not support Kolchak against the rebels in

Siberia. National interests submerged the collective Allied goal. In Britain's

case, it not only worked for its own interests, but it also clashed with the

interests of parts of its own Empire.

In its turn, France

undermined the White Russian General Denikin in favor of the Ukrainian rebels,

despite the agreed Allied aim. France assiduously worked at advancing any

scheme that would ensure Russian payment of the enormous pre-war loans and

massive war debts. This blinkered view of pursuing compensation by any means to

the detriment of common goals steadily undermined collective Allied efforts to

assist the Whites. These illustrate how national self-interest trumped many of

the collective goals.

But the Alliance's

strategic aims in Russia were also fluid. The First World War was the driving

force until November 1918. The Allies' intentions in Russia were to

re-establish the Eastern Front to alleviate German pressure on the Western

Front. The United States, however, did not accept this goal as achievable or

necessary. But with the Armistice, even this goal was no longer relevant, and

the war on Bolshevism became one of many other reasons for intervention. Yet

the Allies could not agree on one policy as it applied to Russia. Moreover,

with the end of fighting in Europe, Russia lost strategic importance in

producing a peace treaty in Paris.

Significantly, Russia

was intimately tied to the laborious and often bitter negotiations at the Paris

Peace Conference. Even well after the Armistice, Allied soldiers were part of

the continued fighting and turmoil across Russia. At Paris and in Allied capitals,

there was fear that Russia could fall under Germany's influence, despite the

latter's defeat in Western Europe. Russia could not be separated from the

larger subject of Germany and its place in Europe. Revolution and tumult were

spreading in Middle and Eastern Europe and Germany. So, while the negotiating

Great Powers did not want Russia present at the Paris Conference, that nation

could not be separated from their talks and decisions. Here was a major

weakness of the Allied interventionist effort: without Russia in Paris, the

Allied intervention was likely doomed to be piecemeal and driven by individual

self-interest. And Russia also had an impact on nations far from its shores.

There were smaller

actions and other motives at play in these events, and mistrust often spread.

In Canada, Sir Robert Borden first urged his government to establish economic

missions to accompany the Canadian contingent destined for Siberia, hoping to reap

economic rewards. Based on the way Britain had acted during the Great War

concerning munitions orders, directing them to the United States and ignoring

Canada's factories, he did not trust the British economic delegation to look

after Canadian interests. For some Canadians in 1919, Russia offered an

opportunity to help recoup the financial cost of the First World War and also

keep the newfound Canadian industrial success going well into the 1920s. So

Canada, like other nations, mixed too many expectations on a policy that should

have been kept as simple as possible, given war's natural characteristic to be

chaotic and uncontrollable.

Personalities had a

major influence on the courses that nations followed. Individuals can often

drive action or cause inaction. Politics and personalities cannot be ignored.

Decisions, in turn, determine what will not be done as well as what is done.

And people made these decisions. Strong-willed people are very important in a

functioning alliance. In the Allied intervention in Russia, there were

influential people at every level of decision-making. The strongest examples in

the actual events and historical interpretation were David Lloyd George,

Winston Churchill, and Woodrow Wilson.

Although some

American historians point their finger at Wilson for singlehandedly causing the

failure of the Allied Intervention, more honestly, it has to be laid at the

feet of more than him. Many others had various shares in this failure, but

besides Woodrow Wilson, another major contributor was British Prime Minister

David Lloyd, George.

George Kennan's

conclusion - blaming Wilson for the outcome - is based more on American

national centrism rather than detailed analysis: that is, Wilson was against

both Russian factions equally because neither lived up to his idealistic

version of the American dream. Initially, Wilson had fought against sending

Allied troops into Russia from a sense of superiority combined with naïveté. He

firmly believed that the Russian Revolution was based on people's desire to rid

themselves of a tyrannical government and establish democracy. Convinced to the

point of unreason, he considered it immoral to interfere in the Russian

people's internal political struggles. The United States had to set an example

to other nations and should not actively interfere on one side or the other of

an internal political fight. Yet as we have seen, Wilson's view was,

ironically, also anti-Bolshevik, although not to the point that he would allow

the US military to assist either faction in Russia. He also deeply abhorred

imperialism. Therefore, he was suspicious and reluctant to act with an entity

he naturally recoiled from, such as the British Empire or a reconstituted

Russian one. He hoped to use the United States' strength to create a new

international order free of war or revolution. It was one in which the United

States would be the pre-eminent political and economic power.

Having the United

States participate in what the president saw as an immoral undertaking would

undermine that nation's image as a ‘shining city on a hill.’ Wilson firmly

believed that the United States was divinely destined to lead the world to an

orderly, liberal, and capitalist international society. Wilson's self-assurance

in his own intellect, coupled with a belief in his own moral superiority, made

him impervious to differing rational argument. Wilson didn't recognize his own

intellectual limits or corrected his mistakes in Siberia. In one author's view,

he had the mind of a country schoolmaster and the soul of an army mule. Wilson

interpreted the First World War as a crusade to make the world safe for

democracy but first viewed that conflict as caused by trade rivalries, which

the United States was supposedly above. Yet the US president was averse to

intervening in Siberia because of trade disagreements with Japan. Moreover, his

antipathy towards the military intervention ensured that US troops involved

would be inadequate for the purpose.

He was not alone.

While Wilson was central to slowing down US participation in the intervention,

Lloyd George almost single-handedly prevented the British from effectively

supporting the Whites. Unlike Wilson, the British prime minister was the

consummate politician who understood the need to keep his electorate happy

while maintaining British prestige and pre-eminence internationally. Like

Wilson, Lloyd George was naive about Bolshevism, seeing it solely as a Russian

problem. He did not understand Lenin's avowed goal of worldwide revolution.

However, he did understand the danger to domestic peace and the desire of Great

Britain's war-weary populace to return quickly to a normal, peaceful regime. In

Lloyd George's mind, British Labour's opposition to

military intervention could have to endanger the whole domestic political

system and Britain's domestic tranquility. Lloyd George knew that Britain could

not afford nor would undertake another major war, especially in Russia, where

the Bolshevik revolution at first seemed to dispose of a dictator and replace

him with a popular government.

But early in the

intervention debate, the British prime minister was supportive of military

involvement when it appeared to be a way of easing pressure on the Western

Front by re-establishing an Eastern Front. His acceptance increased

dramatically in the spring of 1918 when it looked like the Germans' Michael

Offensive would crush the Allies. And so Lloyd George accepted sending Allied

troops to guard military stores at both Archangel and Vladivostok to prevent

their capture by Germany. However, he became skeptical of intervention once the

Armistice was achieved in November 1918. He actively opposed the scheme in both

the British Cabinet and at the Paris Peace Conference. Lloyd George remained

fully sensitive to the manpower limitations of the British Army and the

unaffordable costs any intervention would entail. As the head of a coalition

government dominated by Conservatives, but with strong-willed Liberals as well,

Lloyd George could not afford a single political failure that could be laid at

his feet personally. Fully aware of this, he governed accordingly.

Ever the pragmatist,

Lloyd George's greatest fear was unrest among the British population. In

Russia's view of the Labour Party and articulated by

the Trades Union Congress, military intervention was cause for a General

Strike. For this reason, Lloyd George could not risk openly supporting a

full-scale intervention against the Bolsheviks. He maintained this stance

despite overt pressure from Winston Churchill, the one man who consistently

pushed for a military solution to the Russian problem. To add to the chaotic

nature of British politics was the problem that Lloyd George never quite said

"no" and never quite said "yes" perhaps to cause a delay in

making any decision, thereby gaining time. But whatever the case, such overt

inaction meant that ‘others’ like Churchill took action and were difficult to

control. Nonetheless, it was British Prime Minister Lloyd George's actions and

inactions that prevented adequate British support for the anti-Bolsheviks and,

together with President Wilson, ensured the intervention's failure.

Of course, failure

was also due to purely Russian issues and the Allied leader's ignorance of

Bolshevik's goals. Lenin was a master at chaotic diplomacy. For instance, he

kept the American Red Cross representative Robins and the United States

convinced curing the Brest-Litovsk negotiations to accept Allied help against

the Central Powers. This allowed the Bolsheviks to retain power in Moscow. He

employed similar methods against Trotsky and other Bolshevik leaders to bolster

his personal power. He used diplomatic confusion to gain time against German

negotiations to delay or stop them from a resumption of fighting. And he was

willing to cede Russian territory to ensure the Bolsheviks retained power in

Russia, convinced that world revolution would eventually return all that was

lost.

Even before Lenin

attained power, other Russians made decisions that ensured the Bolshevik

triumph. Without the lies and machinations of Vladimir N. Lvov, it is possible

that Kerensky and General Kornilov would not have had their violent

falling-out. If Kerensky and Kornilov had not become open rivals, it is

possible that the Bolshevik revolution would have failed. And it was personal

distrust, inflated egos, and lies that caused the Kornilov-Kerensky schism.

Other White leaders

also shared similar failings, given their widely divergent political views and

egocentric personalities. Coupled with their personal ambition and frequent

infighting, it also led to turmoil and the final Red success. Denikin, a believer

in a Great Imperial Russia, refused to ally with the Ukraine Nationalist Petlyura to fight the Bolsheviks in South Russia. In the

Baltic, Yudenitch was an arrogant reactionary who

alienated regional allies vital to his access. Consequently, they denied him

the support necessary for victory. In North Russia, Chaikovsky

feared his own military leaders, continuously quarreled with Allied military

commanders over political power and failed to persuade North Russia to support

him. Finally, Admiral Kolchak could not control his own forces and lost the

Czech Legion's confidence, the one capable military force on his side in

Siberia. He also alienated the local population whose support he needed. Also,

the Japanese-backed his Cossack opponents ensuring the White forces were

divided.

Coupled with the

White Russian leadership's incompetence was the individual actions of Allied

personnel on the spot in Russia. Whether it was L-S General Graves in Siberia

refusing to cooperate with the Japanese Allied Commander-in-Chief Otani or

British diplomatic representative Bruce Lockhart in Moscow striving to prevent

Japanese intervention against his own wishes government, individuals enhanced

the diplomatic uncertainty by their actions. Ironside and Maynard in North

Russia worked from a necessity to maintain a strong force and defeat the Reds.

In the case of Ironside, it links the North Russian army with Kolchak's

Siberian army while being bombarded with contradictory orders from Churchill

and Lloyd George over the Allied withdrawal. Both strove for offensive victory

while trying to plan the evacuation of all Allies from North Russia. In

Mesopotamia, General Sir W. R. Marshall interfered with General Dunsterville's Caucasus intervention by first trying to

divert Dunsterforce to face the Turks in Mesopotamia

and then delaying the necessary support for Dunsterville

in Baku until it was too late. General Gough overstepped his authority by

bullying Yudenitch into creating another White

Russian Government for North-Western Russia and recognizing Estonian

independence, which added to London and Paris's diplomatic chaos. And General

Knox wholeheartedly supported Admiral Kolchak up to the latter's ignominious rout

from Omsk despite the blatant incompetence of the Russian military in the fight

against the Reds and the complete inability of the White administration to

govern the Siberian region. These individuals, while not the cause of the

chaos, helped perpetuate and enhance it.

Complicating this was

the vast distance between combat areas in Russia.

This mixture of

internal divisions and space prevented concentrated Allied military aid.

Providing needed material to these diverse and distant areas was exacerbated by

the Allies' chronic logistics and communications problem -lack of sufficient

shipping, a single railway, and the impediments of troops and politicians who

had no desire to fight so far from home.

The revolutions in

Russia caused international turmoil. No one knew where events were leading or

what would occur next. Utter confusion reigned. From the end of 1917, events

often forced governments and leaders to react even though they lacked both the

time and the information to develop a comprehensive strategy. The various

events in Russia stretched the already inadequate Allied resources beyond

effective utility and created the illusion that they were separate and

independent. In reality, they all impacted politically and militarily on each

other.

The British part of

the armed intervention has been among others detailed in books like Churchill's secret war with

Lenin, and more recently also in Churchill’s

Abandoned Prisoners.

Not to mention that

the American military phase carried its own fatal flaws. The first of those was

the inadequate size of the invasion army. The Allies might have been able to

take Petrograd and Moscow with a couple of hundred thousand troops, as Ambassador

Francis suggested, but not with the puny forces they landed at Archangel and

Murmansk. The invasion force at Siberia was larger but still inadequate for a

major offensive.

A second flaw was

animosity between French and American troops and their British commanders. The

inevitable result was a compromise in battlefield cooperation. In his analysis

of the Archangel campaign, U.S. Army historian Peter Sittenauer

wrote that the Western invaders lost the “tempo” of the war as early as October

1918. (He defined “tempo” as the “speed and rhythm of military operations.”) Sittenauer said forces should never operate under foreign

command. They should remain “homogeneous,” with their own officers.7 Blackjack

Pershing had found that out on the western front. It’s a mystery why President

Wilson didn’t learn it from Pershing.

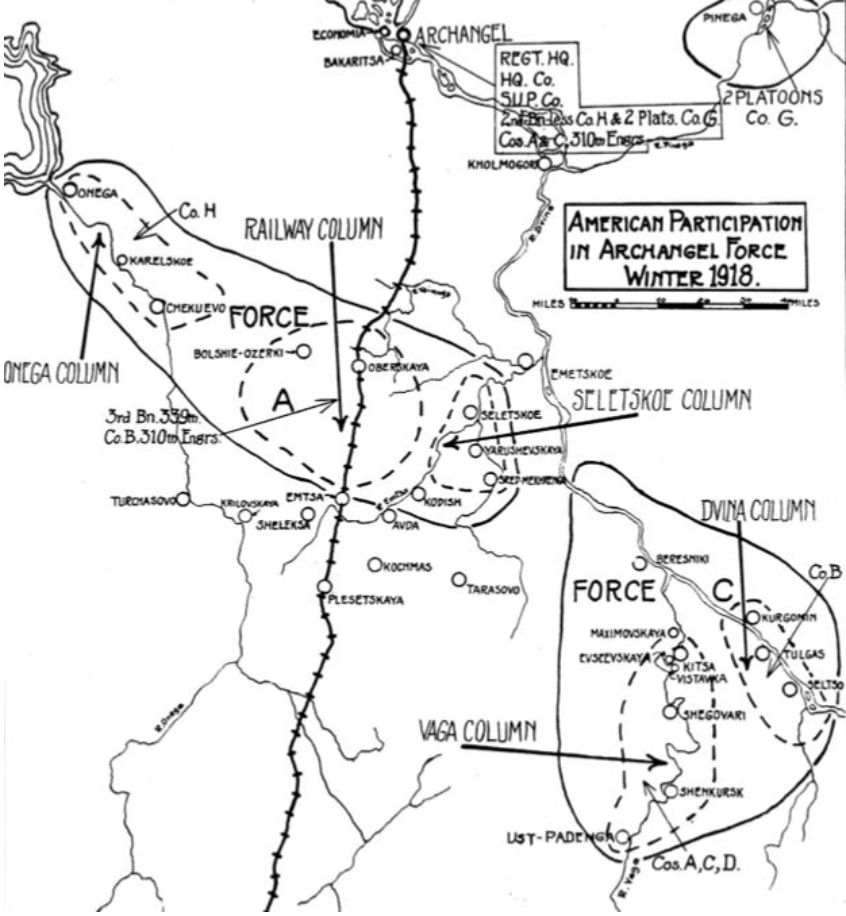

Shenkursk

A third flaw was

underestimating the Red Army. Too many British officers were convinced that

Trotsky’s ragtag force was hopelessly incompetent, no matter how large it got.

However, the most damaging flaw was undoubtedly the tactic of sending

inadequate Allied forces too far into hostile territory without adequate

supplies and reserves. And when General Ironside ordered the Allied columns to

stop advancing and dig in until a new Russian army could be raised, his orders

were ignored by some of his own field commanders. The result was the defeat at Shenkursk.

The fight at Shenkursk began after local British commanders ordered the

Americans to go out and “stir up the enemy” above Shenkursk.

That violated General Ironside’s orders to cease offensive action.

Nevertheless, two patrols of Americans and SBAL Russians went out “seeking

contact.” They were ambushed, and only one man came back.8

On the night of the Shenkursk disaster DeWitt Poole wired the dire news to

Washington:

“We are more and more

put on the defensive, subjected to more and more frequent attacks and

bombardment, suffering many casualties. We have no reserves. Our men are often

called upon to remain on duty for long periods without relief.”9

There was also the

folly of trying to defeat Russians in a Russian winter in the first place.

Russians were accustomed to fighting in a deep freeze. They knew how to

acclimate themselves and turn the weather against their enemies. Napoléon had

learned that. Why didn’t America and the Allies profit from the lessons of

history?

After all the bodies

were counted, the Russians saw the Plot as proof that the West was out to

destroy the Soviet state. Russia was a former ally in the war. She had never

invaded America, France, Italy, or Britain. Russia had not plotted to

assassinate Wilson, Clemenceau, Victor Emmanuel, or George V.

The American

prisoners that were taken in the end were freed by future President Herbert

Clark Hoover, who graduated as an engineer and married his Stanford sweetheart,

Lou Henry, whom he had met, over rocks, in the geology club.

For a few years after

graduation, Hoover worked around the world as a mining engineer. He and his

wife achieved a measure of fame after they helped 120,000 U.S. citizens return

to America from Europe when war broke out in 1914. President Wilson named Hoover

head of the U.S. Food Administration during the war. Then after the peace

treaty was signed, Hoover managed the American Relief Administration in Europe.

He was given almost dictatorial powers to run railroads, docks, and telegraph

systems as he delivered millions of tons of relief supplies to war refugees.

Fridtjof Nansen, a

Norwegian explorer who was also involved in relief work for European refugees,

had warned Wilson in 1919 that “hundreds of thousands of Russians were dying

monthly from sheer starvation disease” and that a Western relief operation should

be organized on humanitarian, not political, grounds.9 In Paris, the Big Four

agreed that supplies could be found, but the main problem would be

transportation and distribution inside Russia. Until all fighting in Russia

ended, a relief operation would be “futile” and “impossible to consider.”10

But by summer 1921,

those hundreds of thousands dying had become millions. One estimate put it at

27 million from starvation alone, including some 9 million children.11

Photographs show butchers selling human arms and legs for food. As before,

Lenin and his government seemed incapable of dealing with it. In Moscow,

Patriarch Tikhon of the Russian Orthodox Church and a fervent anti-Soviet sent

an appeal to the Archbishop of Canterbury in England and the Archbishop of New

York of the famine. “Great part of her population doomed to hunger death,” he

said. Aid needed immediately. “The people are dying, the future is dying.”

Maxim Gorky, a

Russian writer and independent Marxist who had been exiled by Lenin for

opposing the Soviet dictatorship, sent his own appeal: “Gloomy days have come

for the country of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Mendeleyev, Pavlov, Mussorgsky,

Glinka, and other world-prized men,” he wrote. Russia’s misfortune offered a

“splendid opportunity to demonstrate vitality for humanitarianism,” he added.12

Ten days later,

Hoover replied to Gorky, saying certain conditions would have to be met before

U.S. aid could be sent: All Americans had to be freed. American relief workers

had to have complete freedom to do their jobs. Distribution would be on a

non-political basis. The relief workers would need free transportation,

storage, and offices.

Lenin stalled. He was

convinced the aid workers, would-be spies.

Hoover then ignored

Lenin and sent Walter L. Brown to represent the ARA in talks with MaximLitvinov, who

was appointed Soviet plenipotentiary (a diplomat who could act with the full

authority government behind him).

They met at the

Latvian Foreign Department in Riga, and after tedious negotiations, struck a

deal on August 20, 1921. The agreement had twenty-seven sections, all dictated

by Brown. Litvinov signed it, and a hundred American prisoners were on their

way home. “The number was a surprise, as our government knew the names of less

than twenty,” Hoover wrote later. “We served the first meals from imported food

in Kazan on September 21—just one month later.”13

Hoover’s relief

workers issued fifty pounds of corn per month to each person in Russia, along

with bread (real bread) and cans of milk and stew. The children got extra

meals. The cost was one dollar per person per month. The ARA also issued wheat

seeds to farmers. That helped end the famine since many starving Russian

farmers had eaten their seeds. But the 200 American relief officers in Russia

stayed into 1923 to be sure the Soviets didn’t steal food from the children.

Lev Kamenev, chairman of the Moscow Soviet, sent Hoover an elaborate scroll of

thanks, saying the USSR would “never forget the aid rendered to them by the

American people…”14 Hoover’s successful management of post-war American aid to

Europe, including Russia, made his reputation as a major U.S. political and

humanitarian figure.

But Lenin was

determined to have the last word. After the ARA completed its mission and the

Americans went home, many Russians who had worked in the relief operation were

arrested and thrown in prison. Hoover said they were never heard from again.

As for the Plot, this was forgotten or covered up in

America for many years; it was studied and analyzed in the Russian spy school.

And by many seen as the origin of the cold war, succeeding generations of

Soviet bosses have used it to justify stealing thousands of Western military

secrets.

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences in

Russia Part One

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Two

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Three

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Four

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Five

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences in Russia Part Six

1. Petrogradskaia Pravda, September 5, 1918.

2. The National

Archives, London (TNA), FO 371/3326, Lindley to Foreign Office, September 6,

1918.

3. TNA, FO 371/3348,

Bruce Lockhart, “Secret and Confidential Memorandum on the Alleged ‘Allied

Conspiracy’ in Russia,” November 5, 1918.

4. TNA, ADM 137/1731,

Cromie to Admiralty, August 5, 1918.

5. Lockhart, Diaries,

44–45.

6. Lockhart, Diaries,

44–45.

7. Sittenauer, “Lessons in Operational Art,” 43–48.

8. The Chargé in

Russia (Poole) to the Acting Secretary of State, January 23, 1919, 861.00/3713,

FRUS, 1919, Russia.

9. Dr. Fridtjof

Nansen to President Wilson, April 3, 1919, 861.5018/9, FRUS, 1919, Russia.

Nansen was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1922 for his relief work.

10. Messrs. Wilson,

Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Orlando to Dr. Fridtjof Nansen, April 17, 1919,

861.48/15, FRUS, 1919, Russia.

11. Paxton Hibben,

“Propaganda Against Relief,” Soviet Russia, vols. 5–6 (1921): 112.

12. The Minister in

Norway (Schmedeman) to the Secretary of State, July

15, 1921, 861.48/1501, Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic

Papers, The Soviet Union, 1933–1939, 711.61/287a (FRUS), 1921, Russia, Volume

II.

13. Herbert Hoover,

The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover (London: Hollis and Carter, 1952–1953), 23.

14. Hoover, 25–26.

For updates

click homepage here