By Eric Vandenbroeck

Having covered this

subject here and here, it is interesting to note that French

police have ended a decades-long hunt for a fugitive accused of playing a key

role in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, arresting

84-year-old Félicien Kabuga during a dawn raid near Paris.

Kabuga, who is

accused of financing the killings and frequently listed as one

of the world’s most wanted men, was living under a false identity in the

French capital’s suburbs, local police, and prosecutors said in a statement on

Saturday.

French officials said

Kabuga had been hiding

in an apartment in Asnières-Sur-Seine, north-west of Paris, aided by his

children who had set up an effective system to conceal him.

Kabuga also paid

large sums to

establish the hate radio RTLM. His indictment at the ICTR described a

‘strategy devised by fellow extremists, which included several components,

carefully worked out by the various prominent figures who shared the Hutu Power ideology. Kabuga had a

catalytic role in political violence. The experts found the invoices for arms

expenditures and found evidence of payments for ammunition, grenades, and

landmines. There was a high number of low-intensity weapons, cheap to buy, and

easier to stockpile. The main arms suppliers during the 1990–1994 period were

France, Belgium, South Africa, Egypt, and the People’s Republic of China. These

weapons contributed to the huge numbers of victims in the genocide, and to the

speed of the killing.

Midway through their

work, Pierre Galand and Michel Chossudovsky (in La responsabilité des bailleurs de

fonds, Brussels and Ottawa,1996) put important documents on one side in a vault

locked for safekeeping. These included documents they believed useful for

future prosecutions; they then left Rwanda to fulfill professional commitments

in Brussels. But when they returned to the bank some weeks later, they found

the vault empty, their collection missing. They tried to replace the missing

documents by looking for carbon copies in the Ministry of Defence

and Ministry of Finance.

This was not the only

time evidence disappeared. Sometimes the files they needed went missing or

files were spirited away from them so quickly that those seizing them left a

literal trail of paper on the floor, or they would arrive at the right place

and the documents had vanished days before. They soon worked out that the

disappearances were systematic. Galand believed Hutu

Power moles were all over the new administration.1 He suspected there were

people working at the BNR whose intention was to prevent full discovery.

The Rwandans who had

fled abroad and were implicated in the genocide were trying to protect

themselves and were paying bank staff to get rid of certain records. Both Galand and Chossudovsky urgently appealed to senior

officials in the UN Development Programme to help the

new Rwandan government to protect the archives, but they did not receive an

adequate response.

In the three-year

period studied by these experts, one of the poorest countries in the world

became the third-largest importer of weapons on the African continent. The army

increased from 5,000 to 40,000 across all ranks.

Clear warnings to the

World Bank were found in the documents of the BNR. Rwanda was the subject of a

Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) under an

agreement signed in October 1990. In their eventual report in November 1996, Galand and Chossudovsky pointed out that the austerity

measures imposed on the country had no effect on military spending, but

education, health, and infrastructure were all subject to funding cuts. There

were famine and a dramatic increase in unemployment. The incidence of severe

child malnutrition increased dramatically, as did the number of recorded cases

of malaria.2 In a damning conclusion, the experts showed how money to pay for

the genocide preparations came from quick disbursing loans from Western donors

who entered into agreements with the regime stipulating that funds must be used

not for military or paramilitary purposes but for necessary goods such as food

and equipment.

The experts concluded

that the money to pay for the genocide came from loans granted to the regime in

June 1991, from the International Development Association (IDA), the African

Development Fund (AFD), the European Development Fund, and bilateral donors

including Austria, Switzerland, Germany, the United States, Belgium, and

Canada.

The World Bank

president, Lewis Preston, wrote a letter in April 1992 and raised his

objections with Habyarimana about the militarisation

of Rwanda. It came one month after the Rwandan Ministry of Defence

concluded a further US$6 million deal with Egypt that benefited from a

guarantee from French bank Crédit Lyonnais. The first deal in October 1990 for

US$5.889 million was followed by another in December for US$3.511 million. By

April 1991, the Rwandan government had spent US$10.861 million on Egyptian weapons.

In June 1992, a further US$1.3 million was given to Egypt. A November deal

included 25,000 rounds of ammunition, and in February 1993, 3,000 automatic

rifles, AKM guns and 100,000 rounds of ammunition, and thousands of landmines

and grenades. The largest arms deal in March 1992 was for US$6 million for

light weapons and small arms and included 450 Kalashnikov rifles, 2,000

rocket-propelled grenades, 16,000 mortar shells, and more than 3 million rounds

of small-arms ammunition.

Galand

believed that the international financial institutions owed reparations to the

people of Rwanda as a result of their negligence. Five missions were sent by

the World Bank to follow and supervise the Structural Adjustment Programme between June 1991 and October 1993. Only in

December 1993 did the World Bank suspend the payment of a tranche of money

because certain objectives were not met.

The arrest will raise

questions about how he was able to evade

justice for so long and live so close to Paris, at least in recent years.

Kabuga was indicted

by the UN international criminal tribunal for Rwanda in 1997 on seven counts,

including genocide. Following the victory of the Rwandan

Patriotic Front under Paul Kagame, he fled first to Switzerland but was

expelled. It is thought he then travelled to Kinshasa, the capital of the

Democratic Republic of the Congo. He narrowly avoided arrest in Nairobi, Kenya,

in 1996.

The Rwanda tribunal

formally closed in 2015 and its duties were taken over by the International

Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT), which also deals with cases

left over from the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

The arrest of

Félicien Kabuga today is a reminder that those responsible for genocide can be

brought to account, even 26 years after their crimes.

Following the

completion of appropriate procedures under French law, Kabuga is expected to be transferred to the

custody of the IRMCT, where he will stand trial.

Two others who remain

at large are Protais

Mpiranya and Augustin Bizimana.

On 6 April 1994, a

plane carrying then-President Juvenal Habyarimana , a Hutu, was shot down,

killing all on board. Hutu extremists blamed the Tutsi rebel group, the Rwandan

Patriotic Front (RPF) an accusation it denied.

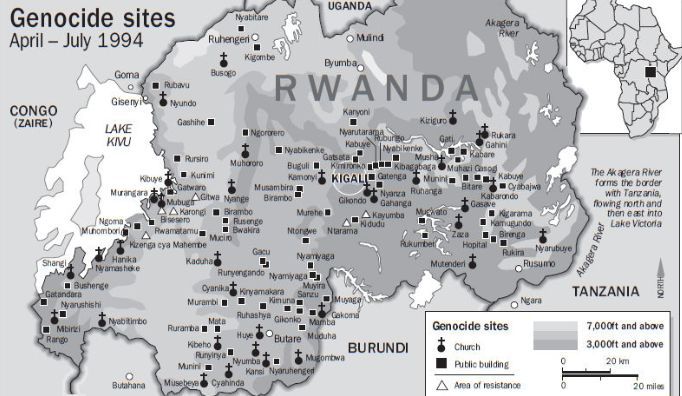

In a well-organized campaign

of slaughter, militias were given hit lists of Tutsi victims. Many were killed

with machetes in acts of appalling brutality.

One of the militias

was the ruling party's youth wing, the Interahamwe, which set up road blocks to

find Tutsis, incited hatred via radio broadcasts and carried out house-to-house

searches.

Little was done

internationally to stop the killings. The UN had forces in Rwanda but the

mission was not given the mandate to act, and so most peacekeepers pulled out.

The RPF, backed by

Uganda, started gaining ground and marched on Kigali. Some two million Hutus

fled, mainly to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The RPF was accused

of killing thousands of Hutus as it took power, although

it denied that.

Dozens of Hutus were

convicted for their role in the killings by the International Criminal Tribunal

for Rwanda, and hundreds of thousands more faced trial in community courts in

Rwanda.

1. L’horreur

qui nous prend au visage, Testimony Pierre Galand, 186.

2. L’horreur qui nous

prend au visage, Testimony Eric Gillet, 228.

3. Rapport sur les

financements du génocide au Rwanda: première expérience d’audit. Interview de Pierre Galand

par Renaud Duterme, 29 Novembre 2016. For the

interview and full report: www.cadtm.org/ Le Génocide.

For updates click homepage here