By Eric Vandebroeck

and co-workers

A review

in the NYT today about How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation by the

longtime Africa specialist Michela Wrong similar to our

2003 article about the subject describes how a cycle of the tragedy began

under European rule when first Germans and then Belgians began formalizing

ethnicity in what is now Rwanda and Burundi. And proceeds with what led to the

April violence between the two groups escalated monstrously in 1972, with a

coup attempt in Burundi, whose ethnic composition mirrors that of Rwanda.

Little heed was paid to it at the time, and Wrong mentions it only in passing,

but the coup turned into one of the worst ethnic killing sprees of the 20th

century. Hundreds of thousands of Hutu were slaughtered by a Tutsi army, and

thousands of others streamed into Rwanda, where tales of their persecution

further radicalized the Hutu majority. Twenty-two years later, the much larger

genocide against Rwandan Tutsi took the world by surprise, but the Burundi coup

had set the stage.

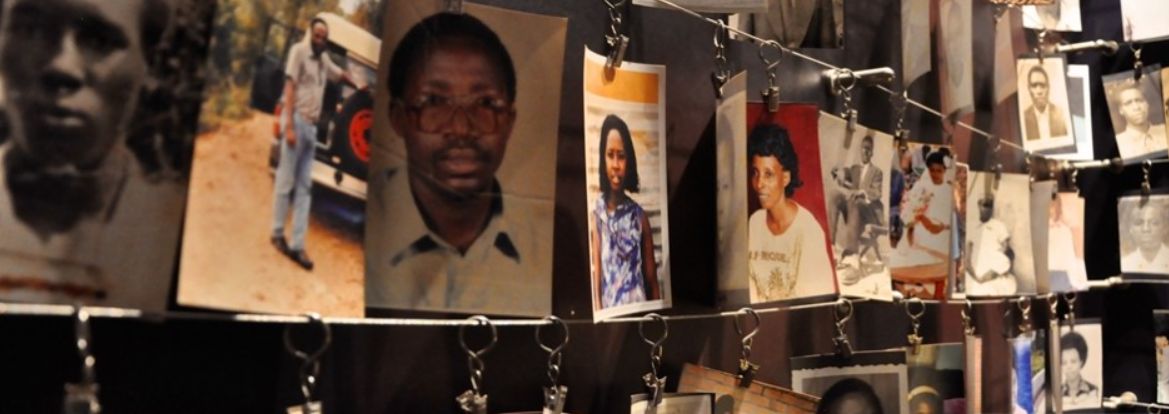

On 7 April, exactly

27 years after the Rwandan genocide against the Tutsis began, Rwanda's permanent representative

to the UN said that a rise in denial of the Genocide against the Tutsi in

academia, media, and even some circles in government institutions, has been

observed.

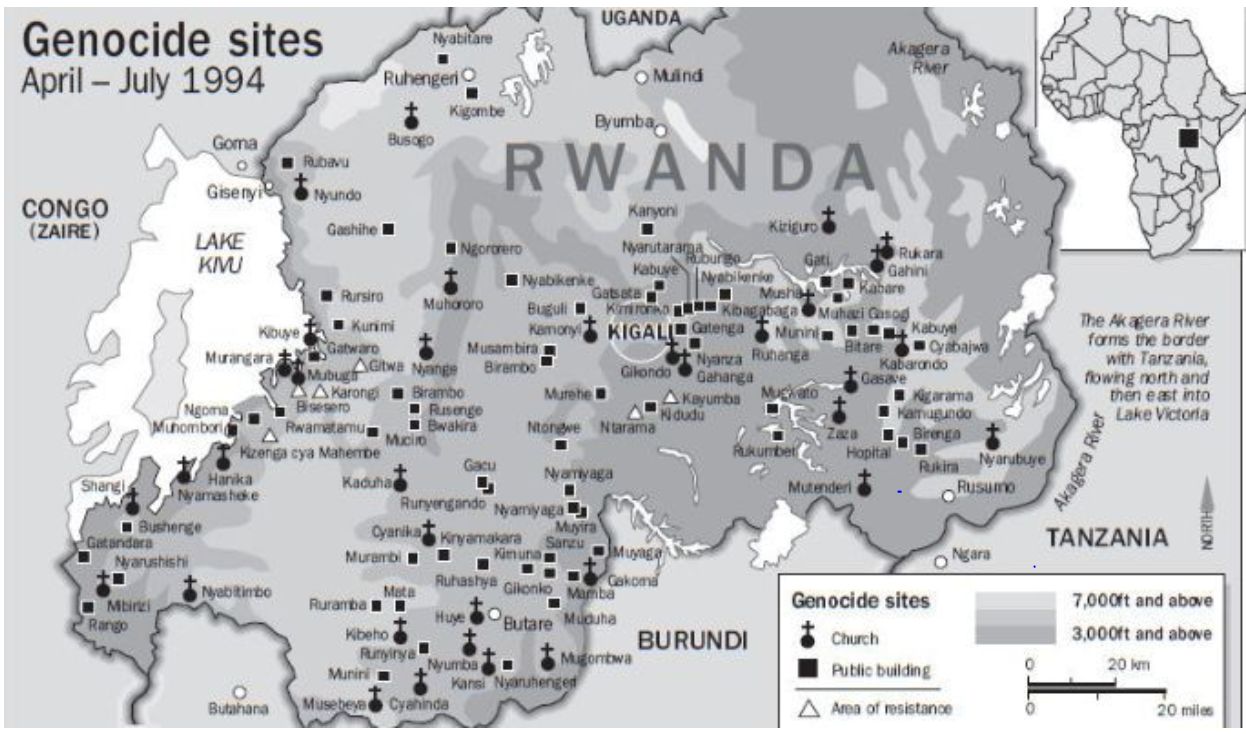

The Rwandan genocide

erupted following the plane crash of then-President Juvenal Habyarimana. For

the next 100 days, armed militias engaged in a killing spree against the ethnic

minority Tutsis and moderate Hutus. In total, some 800,000 people died. The French,

who were allies of the Hutu government under Habyarimana, had sent a special

force to evacuate their citizens and set up safe zones. Although they witnessed

the horror all around them, to this day, they are accused

of having done very little to stop the killing.

As we will see, part of

that might be because some of the perpetrators still have their abode in

France.

Having covered the

subject and from a different perspective in 2003, particularly the French side (which contradicts a disputed article

in the Larousse Junior edition 2020), it is time to revisit this subject.

In fact, since 2003,

there has been a fair share of misleading information, so for example, in The

Politics of Genocide (2010), writers Edward S. Herman and David Peterson, while

not denying the scale of the killing during the period of the extreme violence

of April–July 1994, questioned the distribution of the victims for those

months, arguing among others that Hutus comprised the majority of the dead, not

Tutsis.

Africa

specialist Gerald Caplan rightfully criticized Herman and

Peterson's account, charging that "why the Hutu members of the government

'couldn't possibly have planned genocide against the Tutsi' is never remotely

explained." Herman and Peterson's position on the genocide was found

"deplorable" by James Wizeye, first secretary at the Rwandan High

Commission in London. Adam Jones has compared Herman and Peterson's approach to

Holocaust denial, a term rejected by said authors.

This while U.S.

officials in Rwanda had been warned more than a year before the 1994 slaughter

began that Hutu extremists were contemplating the extermination of ethnic

Tutsis, according to a review panel’s released transcript and declassified

State Department documents obtained by Foreign Policy from the United States

Holocaust Memorial Museum.

An August 1992

diplomatic cable to Washington, written by Joyce Leader, the U.S. Embassy’s

deputy chief of mission in Kigali, cited warnings that Hutu extremists linked

to Rwanda’s ruling party were believed to be advocating the extermination of

ethnic Tutsis. On the morning the killing began in April 1994, there was little

doubt about Rwanda's happening.

A good example of the

denial campaign could be seen when a few weeks before the tenth anniversary of

the 1994 genocide of the Tutsi, in March 2004, a news story on the front page

of Le Monde caused a sensation. It claimed to have untied a Gordian knot and

offered new information about who assassinated President Habyarimana on

Wednesday, 6 April 1994. After six years of investigation, the paper announced

that a French judge determined that the responsibility belonged to the Rwanda

Patriotic Front (RPF) and that the current president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame,

gave the order.1

The story was timed

to perfection, dominating the anniversary coverage and continuing into the

following weeks. The information had come from the office of a French

investigating magistrate, Judge Jean-Louis Bruguière, who, in March

1998, began an inquiry on behalf of the families of the three French aircrews

whose salaries were paid by the French state and who had died in the missile

attack on the Falcon jet. Le Monde claimed the judge had ‘hundreds of

witnesses’ including dissidents, who had spoken of a ‘network commando,’ a hit

squad under the orders of Kagame and responsible for the attack.

The newspaper quoted

a key witness, Abdul Ruzibiza, who explained, ‘Paul Kagame did

not care about the Tutsi living in Rwanda, and they had to be

eliminated.’ Ruzibiza revealed how he had helped to stake out the

assassins' location at a farm in Masaka some four kilometers from the

airport. He saw them arrive in a Toyota, the missiles hidden in the back under

rubbish and empty cardboard boxes. Ruzibiza eventually wrote a book

published in 2005 at over 400 pages, provided a litany of alleged

RPF human rights violations.2

When Le Monde

published its scoop, the trial of Bagosora had

been underway for two years at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

(ICTR). This new element was quickly introduced into the courtrooms and used to

support the idea that Hutu Power was the victim of a monster plot and that a

French judge had proved it. The story in Le Monde supported the claims already

suggested in the trial that the killing was an angry reaction to the death of

the president.3

After the publication

of his report two years later, on 17 November 2006, Bruguière wrote to Kofi

Annan, UN secretary-general, to ask the then prosecutor of the ICTR, Carla Del

Ponte, to take action. He lobbied Del Ponte to put Kagame and the RPF in the dock.

The reaction at the ICTR came from spokesperson Everard O’Donnell, who told

excited reporters the court thought that the assassination did not cause the

genocide.4 In response to the publication of the full report, the Rwandan

government, severed diplomatic relations with France.

Later in November,

Judge Bruguière issued international arrest warrants for nine members of the

RPF he deemed responsible for the assassination. As a classified cable from the

US embassy in Paris informed the state department in Washington, the judge could

simply have gone to Rwanda and asked to interview the nine rather than make

them the objects of international arrest warrants.5 All nine were currently

serving in senior government positions in the government. Kagame himself was

immune from prosecution under French law as a head of state.

In early 2007, Judge

Bruguière met the US ambassador, Craig Roberts Stapleton, in Paris. The judge

admitted to Stapleton that he consulted President Jacques Chirac before issuing

the warrants to ensure the French government was prepared for a backlash from

Rwanda. Bruguière explained that the ‘international community had a moral

responsibility to pursue justice. Stapleton reported how Bruguière did not hide

his personal desire to see Paul Kagame's government isolated and had warned him

that closer US ties with Rwanda would be a mistake. Bruguière casually

mentioned that he was standing for a parliamentary seat later in the year and

that a cabinet post as minister of justice would be his first choice.6

In the years to come,

the story of the guilt of Kagame and the RPF filled books, newspaper articles,

and academic research. Not everyone was fooled.7 Colette Braeckman, a member of the editorial board and African

editor of the Belgian newspaper Le Soir, said she had heard the story

before in an ‘investigation’ produced by an investigator at the ICTR, Michael

Hourigan, an Australian prosecutor researching evidence against Bagosora. Witnesses had come forward just as Colonel Théoneste Bagosora made

his first appearance in court in February 1997. They approached investigators

in a Kigali bar to say they knew all about the assassination and were part of a

secret ‘network’ that Paul Kagame created. They were implicated in the

assassination, they said.

Strangely, however,

none was subject to arrest, and Hourigan told superiors he could not ‘provide

any advice as to the reliability of these informers.8 Hourigan explained how

his team members began to meet former members of the defeated Rwandan army in Kenya

and Europe, who urged them to investigate another ‘possibility’ and the

secretive Paul Kagame. He seemed to believe without question what he was told.

For Braeckman, the only new element in the Le Monde article in

March 2004 was testimony provided by Ruzibiza, the star witness. Braeckman met him a year earlier in May 2003 in

Kampala, Uganda, when he was peddling information about the

assassination. Braeckman had spent the

evening with him when he suggested they write a book together and look for

finance. Braeckman asked about the

topography of the places he mentioned; where had the team of assassins waited?

How did they get

there? How long had they waited? Who told them the plane’s arrival was

imminent? Ruzibiza was confused, said Braeckman,

and unsure of details. She never saw him again and was told later he had gone

to Paris. Braeckman thought the French

intelligence service Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) picked him up and until the story

broke in Le Monde, she had no news of him.9 Braeckman may

not have known that a year earlier, Ruzibiza had been in touch with

investigators from the ICTR, and had given a statement in Kampala in May

2002.10

One claim in the

Bruguière report cast doubt on all the others, calling into question the

thoroughness of his ongoing investigation. In his report, Judge Bruguière

accused the RPF of the earlier assassination in February 1994, only weeks

before the genocide of the Tutsi began, of the popular, moderate, and

conciliatory politician Félicien Gatabazi. Gatabazi was shot three times in the back as he ran

from his vehicle to escape his killers. Bruguière claimed he had information

from witnesses and took this information at face value. As a result, he failed

to acknowledge an investigation carried out by three members of an

international unit of sixty civilian police officers from the UN Civilian

Police (CIVPOL), a UN Assistance Mission component in Rwanda (UNAMIR). Their

inquiries had shown Hutu Power operatives killed Gatabazi, and

the assassination was the subject of a high-level cover-up in an attempt to

blame the RPF. Two vital witnesses, a female taxi driver and a driver for the

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) who saw the killers make a

getaway, died soon afterward, one in a grenade attack the following day and the

other in a supposed suicide.

The CIVPOL officers

had cooperated with the public prosecutor, François-Xavier Nsanzuwera, who conducted his own inquiries into the murder

of Gatabazi immediately after the event. On

28 March, two CIVPOL officers witnessed his arrest of Faustin Rwagatera, the Las Vegas bar manager in Kigali who operated

his own gang of Interahamwe, was a brothel-keeper, and allegedly accompanied

the assassins. He was spotted with four suspects, three of the Presidential

Guards.

When Rwagatera refused to provide information about the

murder, Nsanzuwera charged him with

obstruction of justice and sent him in handcuffs to the 1930 prison.

Immediately afterward, Nsanzuwera received a death

threat and wrote the next day to General Augustin Ndindiliyimana,

the gendarmerie's head, for immediate protection.11 At the same time, the

minister of defense, Major-General Augustin Bizimana, warned the CIVPOL

officers to find a ‘new orientation’ in their work.

Despite these

attempts at the highest level to prevent their investigation, the CIVPOL police

inspectors continued to make headway. They obtained access to the white

Mitsubishi that Gatabazi had abandoned that

night, fleeing a hail of bullets. The police officers retrieved four cartridges

from the vehicle from R-4 rifles used by both Rwandan gendarmes and the army.

The CIVPOL

investigation was further hampered by the Centre de Recherche Criminelle et de Documentation (CRCD), a corrupt

criminal investigation branch of the national gendarmerie, a largely

incompetent force. An officer of the CRCD refused to hand over an AK-47,

complete with a shoulder strap, found hidden near the crime scene. The CIVPOL

officers made sure their superior officers were aware of their difficulties and

sent regular reports on the Gatabazi inquiry

to the head of CIVPOL, Colonel Manfred Bliem, an

Austrian police commissioner.12 They copied their information to the UN special

representative, the Cameroonian diplomat Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh.

Their superiors were informed that they needed to interview senior politicians,

army officers, and Presidential Guards and that there was interference with

their investigation at the highest possible levels in the course of their

inquiries. No one seemed interested.13

Eventually, the

CIVPOL police acquired the names of the alleged organizers of the assassination

and the identities of four suspects who fired the shots. Nsanzuwera believed that if events in April had not

intervened, the case could have gone to trial. Instead, as the genocide of the

Tutsi began, the gates of Kigali’s prisons were opened, and Rwagatera was among the hundreds of prisoners

released. He went looking for Nsanzuwera,

breaking into his house in Rugenge, a

residential district in the capital, on Tuesday, 12 April, along with a gang of

Interahamwe, and found and killed a student, Médard Twahirwa,

Nsanzuwera’s brother-in-law. Nsanzuwera also

discovered that gendarmes and Interahamwe had broken into his office and taken

away his safe.14 Inside were the files on the murder of Félicien Gatabazi that were now lost forever.15

If Judge Bruguière

had wanted to interview Nsanzuwera on what

he knew of the assassination of Gatabazi, again,

he would have been able to do so. After the genocide, Nsanzuwera went

to work in Arusha for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

Here he wrote a landmark report on the Interahamwe for the prosecutors. It

provided a valuable list of the terrorist crimes of this militia between 1992

and 1994.16 From its early beginnings as the youth wing of the presidential

party, Mouvement Révolutionnaire National

pour le Développement (MRND), it had been

transformed into a killing machine. Unlike the other political parties' youth

groups, this was a criminal organization, he wrote, with an effective command

structure, comprising a national committee divided into six commissions. It had

support at the highest level, from the ruling Hutu elite, the gendarmerie's

senior ranks, and the Presidential Guard.

There was no doubt

that the Bruguière report was flawed. Another failure of his argument was the

lack of forensic work, ballistics, or on-the-ground investigation of the crash

site. A credibility gap existed in the report’s material evidence that only included

five photographs showing parts of missile launchers and some serial numbers.

These photographs had already been dismissed in a 1998 French National Assembly

report and could have come from anywhere.17

The story of missile

launchers and serial numbers originated with Colonel Théoneste Bagosora.18

The numbers were on missile launchers apparently discovered by chance on 25

April 1994 on Masaka Hill by an anonymous peasant. The missile parts

were then taken to an army camp where a Rwandan soldier, Lieutenant Augustin Munyaneza, had examined them and written a report. Colonel Bagosora gave the information on the launchers to a

Belgian academic, Filip Reyntjens, who wrote a

book about the assassination. By this time, inconveniently, the launchers had

apparently been taken abroad and given to a Zairean general, where they had

disappeared. According to the Bruguière report, the numbers on these missiles

corresponded with missiles that could be traced and ‘sold by Russia to Uganda

and then given to the RPF.’

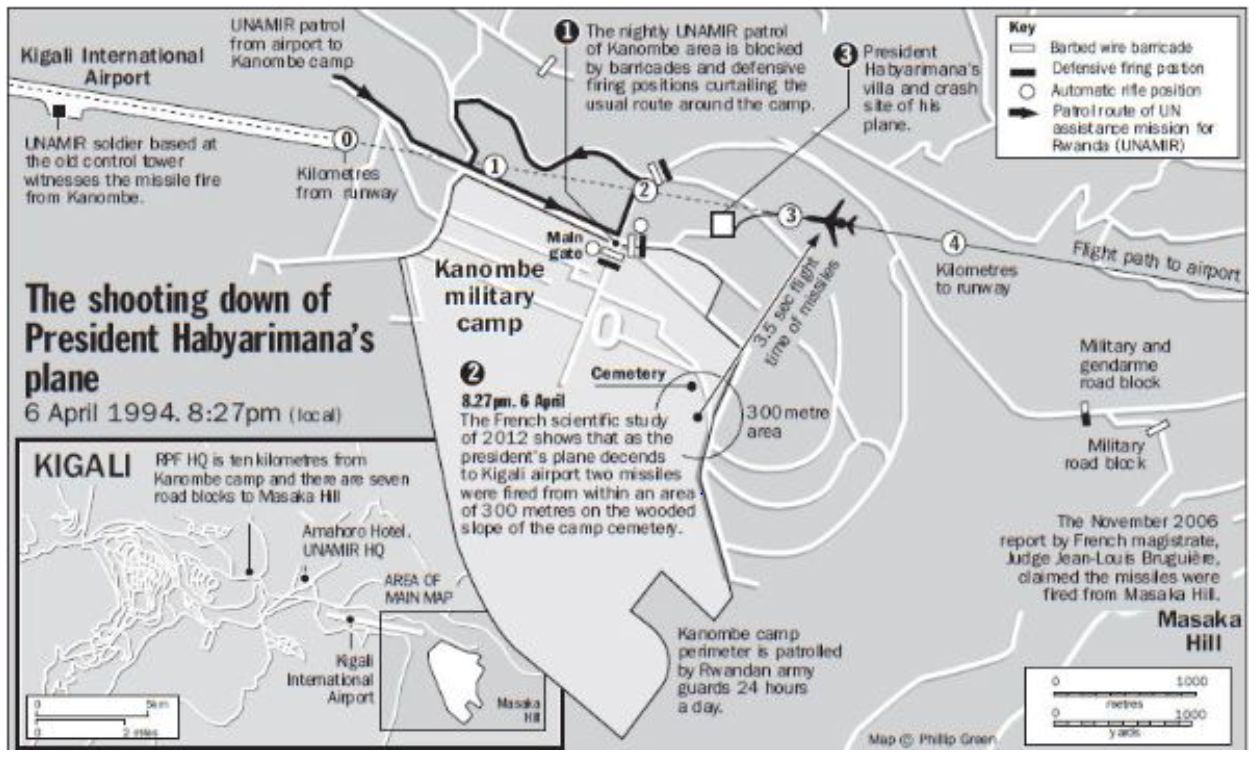

The Bruguière

investigators appeared not to have interviewed any of the direct witnesses to

the event. Within minutes of the assassination, Colonel Luc Marchal,

commander of the Kigali sector of UNAMIR, was aware of two eyewitnesses close

enough to see where the missiles came from, both agreeing it was the military

camp at Kanombe. Another witness, Dr.

Massimo Pasuch, a Belgian military doctor, was

at his home in the heavily fortified Rwandan camp with all windows and doors

open and so close that he distinctly heard the ‘whoosh’ as each missile left

its casing. Pasuch described traces in the night sky as they went towards the

plane. Lieutenant Colonel Walter Balis, the liaison officer between

UNAMIR and the RPF, saw the missiles depart and believed it impossible for the

RPF to infiltrate Kanombe camp. A Belgian

corporal, Mathieu Gerlache, Gerlache, on the viewing platform of a

disused air control tower, had a perfect view as the missiles left from the

direction of Kanombe, the second scoring a

direct hit when the aircraft exploded.

As a result of these

failings, Bruguière received wide criticism for his partial text. He seemed

determined to accuse the president of Rwanda rather than seek the truth.19 This

did not prevent journalists from happily quoting him while not apparently having

read his report. For example, in 2007, the BBC’s Stephen Sackur on HARDtalk accused

President Kagame directly:

You know that Judge

Jean-Louis Bruguière has been working on that case for many, many years. You

also know that he is one of the most respected judges in all of France. He has

a track record of tracking down terrorists, bringing them to justice. He has been

working on your case, and he has, I have it here, about seventy pages of

documentary evidence …

Judge Bruguière comes

up with this conclusion: ‘the final order to attack the presidential plane was

given by Paul Kagame himself during a meeting held in Mulindi on

31 March 1994’. In a major development, the investigating magistrate

Marc Trévidic and his colleague Nathalie Poux assumed

responsibility for the outstanding Judge Bruguière dossiers in Paris. Bruguière

had left the service, having been told that his political activity was

incompatible with judicial duties.20 Trévidic was to become one of

the best-known investigating magistrates in France. In interviews, he made a

point of saying that being a nuisance to governments was exactly what an

investigating magistrate was meant to do. Old investigations never died, he

said. It was often the case that with unsolved crimes, the information could

surface many years later. The dossier he inherited on the assassination of the

presidents of Rwanda and Burundi proved his point.21

Trévidic suspended

the arrest warrants for the nine Rwandan officials, and, with a team of six

French scientists and his colleague Nathalie Poux, he visited the crash

site. The team included experts in missile technology and aviation, air accident

investigators, a geometrician, and an explosives expert. They carried out a

series of tests on the Falcon 50 jet wreckage that remained where it had fallen

sixteen years earlier.

The investigation

broadened in other ways. In the course of the visit, they interviewed

previously ignored Rwandan witnesses who had seen the missile fire in the sky

and took them back to where they had been standing that night. They included

the president’s bodyguards and soldiers from Kanombe camp

who had given evidence to Rwanda’s own commission of experts established in

2008 to investigate the assassination. The commission, named after its chair,

Justice Jean Mutsinzi, a former president of the

Supreme Court, brought in experts from the United Kingdom’s National Defence Academy for scientific advice and analysis.22

In a detailed report in January 2010, it had concluded that Hutu extremists

brought the plane down to destroy the Arusha Accords, and the missiles came

from an area controlled by the Presidential Guard.23

The French judges'

keen interest in the Mutsinzi report was

matched only by a concern to properly understand events in the immediate

aftermath, including the targeted killings of pro-democracy politicians, among

them the prime minister and the president of the Constitutional Court. They

asked for information on the circumstances of the murder of the ten Belgian

peacekeepers. They asked for copies of Hutu extremist newspapers and magazines

and the transcripts of recordings of the hate radio station, RTLM, all of which

predicted that the president would die for having agreed to share power with

‘Tutsi rebels.

An initial 400-page

report published by the French investigating magistrates in January 2012

explained how the first missile missed the plane, but the second ignited 3,000

liters of kerosene in the fuel tank.24 The plane, traveling at 222 kilometers

an hour and an altitude of 1,646 meters, became a ball of fire in

the night sky and, traveling onwards for some seven seconds, eventually hit the

ground, disintegrating as it did so. The plane fell into the presidential

villa's garden, where the president’s wife was preparing a barbecue for her

husband. The mangled bodies of the twelve victims were in the wreckage.

The missile fire

came, in all probability, from a 300-meter radius within the confines of the

most secure army camp in the country at Kanombe,

adjacent to the airport. This domain of some thirty hectares was under

twenty-four-hour surveillance by platoons of soldiers operating a shift system

and linked to the presidential villa by a private track. The missile fire could

only have come from within the camp perimeter, mostly the scrubland to the

south.

The new report

effectively destroyed the Bruguière conclusions that the missiles had been

fired from Masaka, a hill four kilometers east of the airport. The judge

had relied solely on witness testimony, and all of them, including several

convicted génocidaires, convinced him that the

missiles came from Masaka, where a peasant found the launchers. Bruguière

apparently fell for an elaborately staged deception. It was fake news from the

start, intended to cause a diversion, propped up with false statements, manufactured

evidence, manipulated witnesses, and forged testimony.

Jean-François Dupaquier, author and expert on these matters, described it

as having been responsible for malevolent people who had taken part in the

corruption of the judicial process. They aimed to ‘lend support to their

extremist Rwandan friends who launched genocide’.25

On the day of the

report's release, a series of filmed interviews became available, including one

with survivor Esther Mujawayo, author,

sociologist, psychotherapist, and trauma specialist, who lived in Germany and

worked for the Psychosocial Centre for Refugees (PSZ) in Düsseldorf.26 Mujawayo wondered why so many people were taken in:

At last. How could he

[Bruguière] possibly have advanced such a thesis? How could anyone have

believed this for an instant? The intellectuals, people in universities who

were taken in like this? Even if the RPF had magic powers … how

could they have got into the camp? With this lie, a million people died. They

killed my husband. They killed my mother, my parents in law … they killed

everyone … killed the Tutsi because of a fable invented for the purpose that

said ‘their’ president was killed by us [the Tutsi], and they wanted revenge.

She had always known

who was responsible: ‘It was so obvious.’

But the suspicions

persisted.

A panel discussion on

the English-language channel on France 24 included the journalist Stephen

Smith, who broke the story in Le Monde in 2004. A visiting professor of African

& American Studies at Duke University, Smith said that Trévidic provided

a new thrust to the investigation. Still, one should not dismiss the serial

number evidence that traced missiles to Uganda. Smith argued that

the Trévidic report was only part of an ‘ongoing discussion’ and was

‘another element’ to take into account. Smith also maintained his position that

there was no master plan to commit genocide. ‘The special court … charged with

trying genocidal planners and killers has found no one guilty of conspiracy to

commit genocide,’ he claimed in the London Review of Books a year earlier.27

On 22 September 2010,

the key witness for Bruguière, Abdul Ruzibiza, died in Norway, where he

been granted asylum. He turned out to have been a nurse in the RPF and had

pretended to have an inside track, claimed to have known all about the

assassination but at the time was miles away in the north, in Ruhengeri. He

eventually retracted his testimony, like some of the other witnesses involved

with the Bruguière inquiry.28

In October 2006,

another key witness, Emmanuel Ruzigana, had

written to Bruguière to deny he ever belonged to a ‘network commando’ and say

he was ignorant about the plane. He did not speak or understand the French

language and had been interviewed without an interpreter.29 In an interview on

2 December, on Radio Rwanda, Ruzigana said

he had wanted to go to Europe, and a friend at the embassy of France in Dar es

Salaam had helped him out. As soon as he arrived at the airport in Paris, there

had been men who worked in the office of Judge Bruguière waiting for him.

Only later would it

emerge that a Kinyarwanda interpreter used in interviews by Judge Bruguière, a

man at the heart of his investigation, was Fabien Singaye.

This man had operated a European spy ring for President Habyarimana and had

occupied the post of the first secretary at the Rwandan embassy in Bern,

Switzerland. Some of his secret reports were discovered in the abandoned

presidential villa.30 His father-in-law was Félicien Kabuga, the

businessman who provided large sums to finance the genocide and who remains a

fugitive to this day. Singaye was thrown

out of Switzerland in August 1994 and found a haven living comfortably in

France.

Central to the

Bruguière report, however, was testimony from Colonel Théoneste Bagosora. On 18 May 2000, Judge Bruguière spent a day

with Bagosora in the UN Detention Facility

outside Arusha, the first of two visits.31 A transcript produced of the

encounter showed the lack of precise questions that the French judge asked

about the assassination. Furthermore, the transcript left a gaping hole in the

story of the whereabouts of Bagosora on the

evening of 6 April. Bagosora claimed that

between 6:30 p.m. and 8:20 p.m., he had been at Amahoro Stadium

with the Bangladeshi contingent at a reception. A Bangladeshi officer could not

recall this event. Bagosora says he then

returned home at 8:20, where he found his wife in tears on the

doorstep, and she told him the news.

The sound of the

destruction of the president’s plane echoed all over Kigali, but Bagosora appeared to be the only person not to hear

it.32 Bagosora had even been unaware that

the president was going to Dar es Salaam that day. However, in his testimony at

his trial, he said he was already at home when his wife received a call from

the army's general staff informing her that the president’s plane had been shot

down.33

Bagosora told the judge the missile attack on the

aircraft was an international plot abetted by UNAMIR. He suspected the ten UN

peacekeepers, Lieutenant Thierry Lotin and

his men, murdered on 7 April, had a role in this plot. On the day before the

assassination, they had escorted RPF personnel, taking the road that

bypassed Masaka Hill, where the missiles were supposedly

launched. Lotin and his men were seen at

the airport at 8:30 p.m., only minutes after the missile fire. They should not

have been there at all. They had stayed there until 3:00 p.m. when ordered to

go into town to form an escort for the prime minister.

The RPF could not

have accessed Masaka without a convincing escort, said Bagosora, and the most convincing escort was UNAMIR. The UN

peacekeepers had freedom of movement. Therefore, UNAMIR escorted the RPF to the

place from where the missiles were fired. ‘There was a coup d’état by the RPF

with UNAMIR as an accomplice, and with a part of the political opposition,

which was pro-RPF, I tell you,’ Bagosora said.

The most senior

French officer in Camp Kanombe, Major Grégoire de

Saint-Quentin, was an adviser to Major Aloys Ntabakuze,

head of the para-commando battalion at Kanombe.

The French officer was a tall and imposing figure who eventually commanded a

brigade with the French army in Senegal and later in 2013, commander of French

forces in Mali. He is today head of special operations. In April 1994, he was

at his home in the Kanombe military camp

when the missiles were fired at the presidential jet. His garden backed onto

that of the camp commander, Félicien Muberuka,

and he could see the comings and goings on the commander’s driveway.34 The

three large windows in his living room overlooked the flight path, while the

presidential villa was a little more than 350 meters away. Saint-Quentin

recalled that the two missiles' launch seemed so close to him he thought the

camp was under attack.

In a house nearby, a

young girl thought the missile fire sounded like an American movie. She was

sixteen and spent the rest of that night awake, sheltering with her mother and

brothers in the front room, just twelve meters from the road. She, too, thought

the missile fire signified the camp was under attack, but, strangely, there was

no further activity. Normally there were tall and effective streetlights left

on all night, and twenty-four-hour patrols, soldiers on foot and in vehicles,

each group assigned individual zones to patrol. This evening, there was no

activity, no trucks, no patrols, and no sounds of soldiers. At dawn, they crept

out and were told that all the families were leaving the camp, and the

transport was already arranged.

Saint-Quentin had

wanted to retrieve the jet’s black box and remembered two French officers in

helmets who carried torches and searched the smoldering wreckage. The bodies of

the casualties were laid out in a reception room in the presidential villa. Still,

they were removed the next morning in an army truck to a cold store at Kanombe Hospital, where other bodies were piling up in

the morgue.35

Saint-Quentin, in his

interview with the judge, told Bruguière that the Rwandan forces did not have

surface-to-air missiles.36 Perhaps he was unaware of them. Human Rights Watch

believed that when the Rwandan army retreated, it took fifty SA-7 missiles and

fifteen Mistral missiles into exile.37 An army would not keep such an arsenal

if it did not know how to use it. While France officially denied giving

French-made Mistral missiles to Rwanda, this did not mean the Rwandan army did

not have any.

A document found in

UNAMIR archives and prepared by senior officers contained a list of the

military hardware in possession of the Rwandan government army, compiled by the

peace agreement, a list dated 6 April 1994.38 The list included fifteen

French-made Mistral missiles and an ‘unknown quantity of SA-7 missiles. The

force commander of UNAMIR, Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire,

confirmed the list as genuine and compiled with the greatest difficulty from

sources within the military. This information gathered by his mandate. The

missiles, fired at the Kanombe military camp plane,

had effectively destroyed any hope of his resupply by air during the genocide.

‘They had shot down one plane and could shoot down

another,’ Dallaire said. The peacekeepers were unable to guarantee

Kigali Airport's safety, and no company was found willing to insure an aircraft

that the UN had on standby.

In a declassified CIA

report called ‘Rwanda: Security Conditions at Kigali Airport – Capabilities and

Intentions,’ dated 13 July 1994, there is information that Kigali’s

international airport was less dangerous once the RPF had driven out the troops

of the Interim Government. ‘Hutu regime troops, most likely including elements

of the Presidential Guard, were almost certainly responsible for

downing the airplane of the late President Habyarimana as it was landing at

Kigali.’ When the fighting broke out, the Hutu regime had some thirty-five

pieces of air defense artillery, reported a classified informant, as well as

the fifteen Mistral missiles.

Whole sections of

this fascinating eleven-page CIA cable remain classified, and the US was

clearly well informed.39 The carefully planned operation to escort all the US

citizens from the country on 9 April ensured they went by road. From Paris,

information continued to arrive from the ambassador, Pamela Harriman, who told

Washington at the end of April 1994 that her informant said the accusations of

RPF involvement in the assassination were not credible since the site from

which the attack took place was near the president’s residence and was secured

by forces loyal to Habyarimana.

The death of the

president was a signal for a preplanned ethnic massacre to begin. The RPF

offensive towards Kigali began only after the massacres of Tutsi had started.

The signals

intelligence acquired by the US in the crucial first days was said to have

included intercepted telephone calls from extremist officers in Kigali to

counterparts in Gisenyi in the north, as well as communications captured

between politicians and militia and captured information about the downing of

the presidential jet. Likely, the tracking and recording of the entirety of the

local and regional radio traffic were conducted by the National Security Agency

(NSA). In the Maryland headquarters, people fluent in Kinyarwanda were known to

have worked.

The information

gathered contained invaluable evidence of the activities of the génocidaires as they seized power. The US satellite

imagery was such that burning tires and bodies were visible at the roadblocks.

Despite the wealth of

material that undermined the Bruguière conclusion, some people remained

unconvinced and paid no heed to the retraction of the testimony of the

witnesses upon whom the judge had relied. Ignoring the scientific evidence, a

school of thought persisted that pronounced the RPF guilty of the president's

assassination. As a result, there had been no coup d’état.

In a book published

in 2010 that bolstered the earlier Bruguière conclusion of RPF guilt, a

Parisian academic, André Guichaoua of the

Pantheon-Sorbonne University, dismissed the murder of the political opposition

on Thursday, 7 April, as evidence of a coup and called it a ‘recalibrated

political transition,’ simply part of ‘political infighting.’ In this theory,

the RPF downed the jet and deliberately sacrificed the Tutsi

population. No plan had existed to exterminate Tutsi. Not until 12 April, and

the new Interim Government had been installed, was a genocide policy adopted

and a genocide begun. His theory took no account of the targeted killing of

Tutsi at the roadblocks that began on Thursday, 7 April, nor the first

large-scale massacres of Tutsi in Kigali – one in the church grounds in Gikondo in the morning on Saturday, 9 April, to which

UN military observers were eyewitnesses. Another massacre of Tutsi families who

had sheltered at the École Technique Officielle (ETO)

on Monday, 11 April, saw an estimated 2,000 people killed.

These were early

examples of the massacre of large numbers of people that would now recur in a

pattern; Rwandan soldiers and gendarmes sealed exits where Tutsi people sought

shelter and then ushered in the Interahamwe to carry out the killing, thereby

economizing on bullets. It was in Gikondo, on

the afternoon of Saturday, 9 April, the chief delegate of the ICRC, Philippe

Gaillard, recognized that genocide of the Tutsi was by now underway.

In his book published

four years after the Bruguière report, Guichaoua expressed

his belief that the genocide had been a desperate reaction by the most

extremist faction in the face of a military advance by the RPF. Guichaoua categorized the killings as a crime against

humanity committed by a government against a part of its population. Guichaoua wrote the preface for the book by

Abdul Ruzibiza, the star witness used by Judge Bruguière, who had first

introduced the witness to the judge and had persuaded Ruzibiza to

write a book.40

Another member of

this school of thought is the acknowledged expert René Lemarchand, a

French-American political scientist known for his work on Rwanda and Burundi

and professor emeritus at the University of

Florida. Lemarchand insisted the RPF downed the plane. He disparaged

the Mutsinzi report and noted in 2018 that

‘all facts pointing to Kagame’s responsibility were conveniently ignored.’ He

failed to specify which particular facts he meant. ‘The scantiness of the

evidence notwithstanding, the notion of a criminal plot concocted by Hutu

extremists is still the standard explanation advanced,’ he

wrote. Lemarchand believed it a subject fit for debate as people took

up several ‘contradictory positions’.41

Reyntjens, emeritus professor of law and politics at the

University of Antwerp, remained an advocate for the Bruguière report and wrote

about the existence of a ‘whole heap of indications’ that showed the RPF was

responsible for the assassination. In an account of events published in

2017, Reyntjens omitted any mention of

scientific reports about how missiles came from the Kanombe military

camp, which was inaccessible to the RPF. Reyntjens seemed

unaware of the existence of witnesses in Kanombe camp

that night. Reyntjens did not believe in

genocide planning and said the killing happened because of the aggression of

the regime's enemies that set off a chain reaction that led to it. The RPF had

a historical and political responsibility in the extermination of the Tutsi.42

The story

about Masaka Hill lingered on, the scientific and direct eyewitness

testimony continually ignored. In 2017, in a book by Helen C. Epstein, Another

Fine Mess: America, Uganda, and the War on Terror, the author accused President

Paul Kagame of the assassination, repeating the claim in an extract from the

book in the Guardian.43 The missiles came from Masaka Hill, she

wrote, and the weapons used were Russian-made SAM-16s because ‘two SA-16

single-use launchers’ were found near the launch site. She relied on the report

by French investigating magistrate Jean-Louis Bruguière. She pointed out that

the serial numbers on the Masaka launchers came from a consignment

shipped from Russia to Uganda. Her source was Filip Reyntjens, who

told Epstein the weapons were Russian-made SAM-16s. He said that ‘two SA-16

single-use launchers’ were found near Masaka Hill, a place more

‘accessible’ to the rebel fighters of Kagame’s RPF than the Kanombe military camp. What Reyntjens may

not have told her was that the information about launchers

at Masaka Hill and their serial numbers originated with the prime

suspect, Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, a convicted génocidaire.

With little fanfare,

on 24 December 2018, French magistrates in Paris dropped the case brought

against the nine senior RPF leaders suspected of the assassination of President

Habyarimana and for whom there had been international arrest warrants issued. The

twenty-year investigation had ensured the real culprits escaped scrutiny.

The 11 January 1994 cable

An 11 January 1994

cable was difficult to ignore. As a piece of material evidence in court, it

caused severe problems for defense lawyers. It was, perhaps, the most famous

fax in UN history. Sent from Kigali to the UN Secretariat in New York by Lieutenant-General Roméo

Dallaire, it gave details of preparations then underway to register all

Tutsi families in Kigali with a view to their extermination.

The information it

contained came from an informer, a coordinator with the Interahamwe militia,

who claimed intimate knowledge of the Hutu Power movement's activities. He said

lists of Tutsi were being compiled in each sector (termed "secteur" administrative subdivision), going from house

to house, noting every family member. Following this intelligence gathering,

every secteur was provided with a militia of forty

operatives trained to kill at speed. Each group had been secretly trained in

weapons, explosives, close combat, and tactics. Within twenty minutes of

receiving the order to kill, the militia in each secteur

could immediately murder 1,000 people. There were hidden stockpiles of weapons

all over the city.

The informer warned

that President Juvénal Habyarimana had lost control over his old party, the Mouvement Révolutionnaire

National pour le Développement (MRND). Furthermore,

the informer told of plans to goad the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) to scupper

the peace agreement and restart the civil war. In violent, coordinated, and

preplanned demonstrations, the Interahamwe would provoke Belgian peacekeepers

and kill some of them to guarantee the contingent's withdrawal, the backbone of

the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR).

The full text of the

famous two-page 11 January fax to UN headquarters emerged in its entirety a few

weeks later and received international press coverage to prove the

extent of the failure over Rwanda. In later years the fax was part of the

prosecution in the trials of the génocidaires at the

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), disproving the many claims

from defense lawyers that the slaughter had been spontaneous.

For this reason, the

defense lawyers tried to turn the court's attention away from the information

contained in the fax to the informer himself. They launched a sustained attack

on his reputation, and one of the defense lawyers at the ICTR was the Canadian

Christopher Black. In 2002, he had defended the former commander of the

national gendarmerie, Major-General Augustin Ndindiliyimana,

who in April 1994 was in charge of maintaining public order and who was accused

of genocide in the trial known as Military Two. In the courtroom, Black was

determined to nullify the fax and told the trial chamber that Jean-Pierre was a

double agent who worked for the RPF and had set out to smear President Juvénal

Habyarimana.

As New Yorker

reporter Philip Gourevitch dubbed it in 1998, the

Dallaire genocide fax was probably doctored a year after Rwanda's mass killings

ended. In a chapter devoted to the fax in Enduring Lies: The Rwandan Genocide in the Propaganda

System, 20 Years Later, Edward S. Herman and David Peterson argue two

paragraphs were added to a cable Dallaire sent to Canadian General Maurice

Baril at the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations in New York about a

weapons cache and protecting an informant (Dallaire never personally met the

informant). The added paragraphs said the informant was asked to compile a

Tutsi list for possible extermination in Kigali and mentioned a plan to

assassinate select political leaders and Belgian peacekeepers.

At the ICTR, former Cameroon

foreign minister and overall head of the UN mission in Rwanda, Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh, denied seeing

this information. There’s no evidence Dallaire warned the Belgians of a plan to

attack them, which later transpired. Finally, a response to the cable from UN

headquarters the next day ignores the (probably) added paragraphs. Herman and

Peterson make a compelling case that a doctored version of the initial cable

was placed in the UN file on November 27, 1995, by British Colonel Richard M.

Connaughton as part of a Kigali-London-Washington effort to prove the existence

of a plan by the Hutu government to exterminate Tutsi.

Even if the final two

paragraphs were in the original version, the information's credibility would be

suspect. Informant “Jean-Pierre” was not a highly placed official in the

defeated Hutu government, reports Robin Philpott in Rwanda and the New Scramble for Africa: From Tragedy to Useful

Imperial Fiction. Instead, “Jean-Pierre” was a driver for the MRDN political

party who later died fighting with the Rwandan Patriotic Front.

Incredibly, the

“genocide fax” is the primary source of any documentary record demonstrating

the UN foreknowledge of a Hutu “conspiracy” to exterminate Tutsi, a charge even

the victor’s justice at the ICTR failed to convict anyone of. According to

Herman and Peterson, “when finding all four defendants not guilty of the

‘conspiracy to commit genocide’ charge, the [ICTR] trial chamber also dismissed

the evidence provided by ‘informant Jean-Pierre’ due to ‘lingering questions

concerning [his] reliability.’”

Tellingly, Dallaire

didn’t even initially adhere to the “conspiracy to commit genocide” version of

the Rwandan tragedy. Just after leaving his post as UNAMIR force commander,

Dallaire replied to September 14, 1994, Radio Canada Le Point question, saying,

“the plan was more political. The aim was to eliminate

the coalition of moderates. … I think that the excesses that we saw were beyond

people’s ability to plan and organize. There was a process to destroy the

political elements in the moderate camp. There were a breakdown and hysteria

absolutely. … But nobody could have foreseen or planned the magnitude of the

destruction we saw.”

Doctoring fax to make

it appear the UN had foreknowledge of a plot to exterminate Tutsi may sound

outlandish. Still, it’s more believable than many other elements of the

dominant narrative of the Rwandan genocide. For instance, the day after their

editorial, the Star published a story titled “25 years after the genocide,

Rwanda rebuilds,” which included a photo of President Paul Kagame leading a

walk to commemorate the mass killings. But, Kagame is the individual most

responsible for unleashing the hundred days of genocidal violence by downing a

plane carrying two Hutu presidents and much of the Rwandan military high

command.

The Toronto Star

published a story titled “Did Rwanda’s Paul Kagame trigger the genocide of his

own people?” For its part, the Globe and Mail have published a series of

front-page reports in recent years confirming Kagame’s responsibility for

blowing up the plane carrying Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana, which

triggered mass killings in April 1994. In an October story titled “New information supports claims, Kagame forces were

involved in an assassination that sparked Rwandan genocide,” the Globe all but

confirmed that the surface-to-air missiles used to assassinate the Rwandan and

Burundian Hutu presidents on April 6, 1994, came from Uganda, which backed the

RPF’s bid to conquer its smaller neighbor. (A few thousand exiled Tutsi Ugandan

troops, including the deputy minister of defense, “deserted” to invade

Rwanda in 1990.) These revelations strengthen the case of those who argue that

responsibility for the mass killings in spring 1994 largely rests with the

Ugandan/RPF aggressors and their US/British/Canadian backers.

By presenting the individual

most culpable for the mass killings at the head of the commemoration for said

violence, the Star is flipping the facts on their head. The same might be said

for their depiction of the Canadian general. At the end of their chapter

tracing the history of the “genocide fax,” Herman and Peterson write, “if all

of this is true,” then “we would suggest that Dallaire should be regarded as a

war criminal for positively facilitating the actual mass killings of

April-July, rather than taken as a hero for giving allegedly disregarded

warnings that might have stopped them.”

Also, in US documents

that have been declassified, there are numerous redactions. A scandal exists in

France where successive governments have prevented access for historians and

journalists to crucial military and political archives, including those of President

François Mitterrand and the officials who worked in his unaccountable Africa

Unit in the Élysée Palace.

As we detailed in our initial 2003-4 case study,

France has long faced charges that supported the Hutu leadership before and

even during the massacres. President Paul Kagame of Rwanda has called French soldiers “actors” in the genocide, a charge

denied by the former French prime minister, Édouard Balladur, as “a

self-interested lie.” But on Friday, President Emmanuel Macron of France ordered

a two-year government study of France’s role in the Rwandan genocide.

French judges have

heard from a new witness who claims to have seen missiles allegedly used to

kill former Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana, whose death sparked genocide

in 1994, a source close to the case told AFP on Monday.

The witness says he

saw two surface-to-air missiles at the headquarters of the Tutsi militia headed

by current

Rwandan President Paul Kagame, which were later used to take down

Habyarimana's plane.

A consequence of excessive

government secrecy is the opportunity it afforded the génocidaires.

An information vacuum gave them free rein to spread lies and disinformation to

deny their crime. They deceived the Western press, promoting lies faster than

the facts could debunk them.

Thus, in September

2016, the chief propagandist of Hutu Power, Ferdinand Nahimana, walked free

from prison, having served twenty years and six months in international

custody.44 It was thirteen years since his conviction to a life term imposed in

a courtroom at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), where he

was found guilty of genocide, direct and public incitement to commit genocide,

conspiracy to commit genocide, crimes against humanity (persecution) and crimes

against humanity (extermination).45

For the survivors of

the genocide of the Tutsi, his release was a devastating development. The

decision betrayed a lack of understanding of the crime of genocide and failed

to acknowledge its magnitude. Nahimana continued to claim his innocence. Given

the Hutu Power propaganda produced by Nahimana and his fellow génocidaires, these prisoners continued to promote the same

poisonous and racist ideology that motivated their criminal acts in 1994. To

have released Nahimana at a time when genocide denial was more entrenched than

ever was irresponsible. The decision showed contempt for the survivors and

their continued suffering.

The Rwandan minister

of justice, Johnston Busingye, called for the removal of the US judge

responsible, Theodor Meron. In coming to his decision, Meron had held no

hearings, took no account of the survivors' views, and had given no say to the

government of Rwanda. His decision was secret and unaccountable. No appeal was

possible. A brief official explanation came in the form of a short, redacted

report that provided necessary background information.46 It included glowing

testimonials from prison wardens who described Nahimana’s impeccable conduct.

In his prison career, Nahimana had lived ‘in perfect harmony with fellow

inmates and the prison administration. He was polite, disciplined, and would

quickly reintegrate into society as someone ‘humble and courteous.

Nahimana served his

sentence in a community with his colleagues, a group of Rwandan génocidaires who lived together in a purpose-built compound

within the high-security Koulikoro prison, some thirty-five miles (fifty-seven

kilometers) from Bamako, the capital of Mali.47 The special compound,

constructed at United Nations expense, was segregated from the misery found in

the rest of the prison. Within yards of this ‘international wing,’ there were

unsanitary conditions, overcrowding, a lack of medical care, and not all the

prisoners had access to potable water. The génocidaires,

on the other hand, had separate cells, showers, a gym, a well-stocked library,

a dining room, and a church.

The UN, an

organization, intended by its founders to uphold human rights, required that

the Rwandan génocidaires live in conditions that met

the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (SMRs). Initially

adopted by the UN Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of

Offenders in 1955, they were given final approval by the UN Economic and Social

Council in 1957.48 Conditions had to comply with the Body of Principles for the

Protection of all Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment, approved

by UN General Assembly resolution 43/173 of 9 December 1988, as well as the

Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners, affirmed by UN General

Assembly resolution 45/111 of 14 December 1990. These requirements are

non-binding on UN member states. To ensure the proper application of these

international standards, the particular compound in the Koulikoro prison

received visits from global humanitarian groups, including the International

Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

In this special

community, according to the wardens, Nahimana had a crucial role. ‘It was quite

an achievement among a group of intellectuals in which each member is intent on

promoting his ideas.’ They praised his character and personality. A former warden

noted the contribution of Nahimana to the smooth running of the unit: he helped

to ‘restrain and keep his compatriots in check.’ Even the Ministry of Justice

in Mali weighed in with a letter to support his early release, telling Judge

Meron that between 2009 and 2013, Nahimana was the ‘Rwandan group’

representative, helping his fellow inmates ‘resolve many issues.’

A psychosocial report

described his behavior as exemplary. He was ‘always willing to listen to his

co-detainees.’49 Furthermore, Nahimana submitted his petition for release,

written by three lawyers. They stressed his family ties, which he managed to

maintain, and that he hoped to ‘work for peace and reconciliation in Rwanda.

However, it was not explained by the lawyers how this might be achieved.50

Meron wrote in his report that the prisoner showed ‘some signs of

rehabilitation.’ The judge seemed not to care that Nahimana continued to deny

his responsibility in ‘these crimes.’ While his lawyers maintained that their

client did not question or minimize ‘the genocide,’ or his ‘profound regret’

for the ‘crimes committed in Rwanda,’ what he did not accept was a role in the

broadcasts' criminal nature RTLM. Nahimana had not once offered to help the

office of the ICTR prosecutor. This was something Meron regarded as a ‘neutral

factor.’

It remains unclear

whether the judge critically assessed the information he received about

Nahimana. His short report contained no detail at all about how the prisoner

was ‘rehabilitated.’ Afterward, there were doubts expressed about the capacity

of the prison authorities in Mali to develop rehabilitation programs for these

Rwandan prisoners, particularly given the language and cultural differences.51

In their special

compound, the génocidaires kept in touch with world

events, received frequent visitors, and were interviewed by journalists and

academics. They received $2 a day to buy newspapers, and payment was

provided for telephone calls. They posed no problems for the prison authorities.

They spent their time working on their campaign of denial, and the facilities

provided for them helped them write books and communicate with publishers who

were willing to produce their work. The prison warders noted how educated these

prisoners were and how they kept to themselves and worked on their ‘political

activities’. A member of the Koulikoro prison management gave a radio interview

in which he explained that these prisoners demanded ‘justice for all victims without

exception,’ whether Tutsi or Hutu.52

From the special

compound in Mali and another prison in Benin, the génocidaires

continued to protest their innocence, influence newcomers to the subject, find

new and receptive audiences, and seek out conspiracy theorists and gullible

journalists and academics. Their written work repeated the familiar stories of

genocide denial. How more Hutu people died than Tutsi, how the killing was

self-defense, the deaths not intentional, there was no planning and no central

direction, and the Hutu were the real victims. From this particular compound,

the chief propagandist, Ferdinand Nahimana, had two books on sale on Amazon (in

France), and the author described himself as a political prisoner.53 In their

community, the génocidaires spent time analyzing

numerous ICTR and UN documents and wrote appeals to the authorities. Only the

truth could save the people of Rwanda, wrote Nahimana.54

The supporters of

their campaign of denial praised the Mali prison authorities for not succumbing

to ‘the demonization of Rwandan Hutus’ that had turned them into monsters in

Western public opinion. These men deserved our pity. They had been uprooted from

the lush green lands of home to a hot, dry, and dusty Mali. Furthermore, Rwanda

was a Christian and Mali Muslim. The Montreal journalist and publisher Robin

Philpot wrote: ‘For prisoners convinced of their innocence, the worse problem

is the distance from their families.’ Philpot wrote about ‘the colonial nature

of these new forms of UN-sanctioned penal colonies.’ How could they make their

cases known and hope to reopen them? This was nothing less than banishment, and

these prisoners were condemned to a long slow death. Philpot reported

complaints from the génocidaires that they ‘had been

made to disappear from the news.’55

This was not strictly

true. An invaluable glimpse inside Mali's special compound, where the génocidaires lived, came in filmed footage broadcast on ITV

news in the UK on 21 July 2015. It was billed as a world scoop and was an

interview with Jean Kambanda, the world’s first head of government to plead

guilty to the crime of genocide. The Africa correspondent for ITV, John Ray,

had gained access to a top security prison, he said, that housed the men behind

Africa’s ‘final solution.’

The on-camera

interview with Kambanda, economist and banker, the prime minister of the

Interim Government that oversaw the extermination program of the Tutsi, took

place in the library. Kambanda was the world’s highest-ranking political leader

held to account for the crime of genocide, and he was serving a life term, but

he had later retracted his plea. In the television footage, Kambanda walked

through gardens with a briefcase and talked and laughed with the British

journalist. He appeared portly, having gained weight since the last day of the

trial in September 1998. He began the interview in faltering English, ‘I cannot

express any regrets for something I have not done. Someone else did it.’ The

truth was still in dispute, the journalist said at the end. Kambanda admitted

to Ray that he had distributed weapons, but only so people could protect

themselves. His conscience was clear. He had been a ‘puppet’ and felt no sense

of guilt. ‘We are fighting to be free,’ Kambanda told Ray.

After the

announcement of the release of Ferdinand Nahimana, Justice Navi Pillay, the

South African judge who presided in the media trial at the ICTR, said no one

had consulted her about the early release of Nahimana, and, as the presiding

judge in the trial, she thought this would have been appropriate. Pillay

expressed concern at the lack of any post-release conditions imposed on

Nahimana and wondered why no realistic possibility existed to monitor him,

supervise his activities, or determine whether his racist propagandizing

continued. Meron had simply granted ‘an irreversible and unconditional form of

release, an unconditional reduction in the sentence’ that had resulted in

complete freedom. The decision threatened the credibility of international

justice, Pillay believed.

That Meron had

decided the fate of Nahimana after having earlier played a role in reducing his

sentence on appeal was of concern. On 28 November 2007, the Appeals Chamber had

reduced Nahimana’s life sentence to thirty years. Meron had written a dissenting

view in the appeal judgment, wanting to reduce further the thirty-year sentence

agreed upon by the two other appeal judges. He thought the punishment of thirty

years too harsh. In his dissenting view, Meron was scathing the media trial and

pointed to the ‘sheer number of errors’ in the trial judgment. He called for a

new trial because ‘mere hate speech was not the basis for a criminal

conviction.56 Meron believed that the liability connected to hate speech was

illegitimate in light of freedom of expression, and this was explicitly

grounded in the free speech guarantee of the US First Amendment.57

I believe that the

only conviction against him that can stand is for direct and public incitement

to commit genocide under Article 6(3) and based on specific post-6 April

broadcasts. Despite the severity of this crime, Nahimana did not personally

kill anyone and did not personally make statements that constituted incitement.

In light of these facts, I believe that the sentence imposed is too harsh, both

about Nahimana’s culpability and the sentences meted out by the Appeals Chamber

to Barayagwiza Ngeze (co-accused),

who committed graver crimes. Therefore, I dissent from Nahimana’s sentence.

Fellow ICTR judges

were not alone in their concerns at these developments. Professor Gregory S.

Gordon, professor of law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) Faculty

of Law, worked on the media trial from its beginnings and was an expert on atrocity

speech in the circumstances of the 1994 genocide of the Tutsi. Gordon, who had

helped gather prosecution evidence, believed that the media trial was so

significant that it had helped define the distinction between hate speech and

speech used to incite genocide from a historical perspective.

Gordon published

Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition in 2017. In an

interview in London that year, he explained the crucial role of Ferdinand

Nahimana and claimed that, without him, the hate radio RTLM would not have

existed. The connection between hate speech and atrocity in Rwanda was so

secure that the media trial ‘served as a virtual laboratory for the development

of atrocity speech law.’58 Ideology and propaganda were integral to the crime

of genocide, and the 1994 genocide of the Tutsi of Rwanda showed how mass media

was a causal factor in mass atrocities.

A direct challenge to

the views of Meron on free speech came in a foreword to Gordon’s book, written

by a Nuremberg prosecutor, Benjamin B. Ferencz. Ferencz believed a failure to

criminalize hate speech served only to encourage fanatics, for example, those

responsible for the genocide of the Tutsi. He added: ‘The first amendment to

the US Constitution that guarantees freedom of speech was never intended to

justify the violation of fundamental human rights designed to protect

everyone.’ Hatred generated by vicious propagandists such as Julius Streicher

was one of the main reasons the Nazi crimes could be committed.

Curbing hate speech

was a way to prevent genocide, for it was the case that arousing public fears

could incite it. ‘We have still not recognized that you cannot kill an

ingrained ideology with a gun,’ wrote Ferencz. Gordon recalled a dearth of

jurisprudence to guide them from the start of the media trial. As the tribunal

geared up in 1996, on one set of shelves in an almost empty library was a

complete set of the transcripts of the trials at Nuremberg.59

Judge Theodor Meron

had never sat through a genocide trial. He served only on the Appeals Chamber

and so did not experience the agonizing testimony in the trials. He did not

participate in the debates among the judges about the appropriate length of

sentences imposed on the génocidaires for their

unspeakable crimes. In her interview, Judge Navi Pillay carefully explained why

the judges had decided to impose life sentences in the courtrooms of the ICTR,

something the trial judges had discussed at length and taken seriously. The

scale and magnitude of the crime were never in doubt from the very first trial,

Pillay explained, nor its brutality.

Pillay was one of

three judges in the world’s first genocide trial held at the ICTR to hear the

case of Jean-Paul Akayesu, a middle-ranking official

in local government, a bourgmestre (mayor), a

teacher, and schools inspector. Found guilty of nine counts of genocide, direct

and public incitement to commit genocide, and crimes against humanity – these

included extermination, murder, torture, rape, and other inhumane acts – his

life term was confirmed on appeal.

The trial of Akayesu made legal history in another way. The crime of

rape was not initially in the indictment. Still, in the course of the trial,

and after questioning from Pillay, the testimony from prosecution witnesses

revealed the level of sexual crimes in the genocide. Without Pillay, the courts

might never have addressed this aspect of the genocide, and she went on to

ensure groundbreaking jurisprudence on rape as a crime of genocide. It was a

significant milestone and determined that sexual violence was an integral part

of the process of destruction: the Akayesu judgment

noted, ‘Rapes resulted in physical and psychological destruction of Tutsi

women, their families, and their communities.’60

The collection of

data to determine instances of rape and sexual violence had been fraught with

problems. Today, an accurate number cannot be set. Most experts believe it to

be in the region of 250,000 rapes and sexual assaults.61 The sexual violence in

Rwanda included sexual slavery, forced incest, deliberate HIV transmission,

forced impregnation, and genital mutilation.62 The sexual attacks intended to

humiliate, demoralize, and enslave. The evidence in the Akayesu

trial had shown Tutsi women targeted for sexual violence, which had contributed

to the destruction of the Tutsi group as a whole. In the media trial in 2003

over which Navi Pillay presided, there was expert and witness testimony that

confirmed Hutu Power propagandists had targeted Tutsi women, the targeting

woven into the planning of the genocide in 1994.

In the light of all

this evidence and the magnitude of the crimes, the imposition of life sentences

was appropriate, said Pillay. This was widely accepted by ICTR judges who

expected the génocidaires to serve their sentences in

full. Only those who confessed and cooperated with the prosecutor were eligible

for early release. The tribunal attached significant value to ‘voluntary,

substantial, and long-term cooperation with the prosecutor.’

When appointed

president of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (MICT)

in 2012, known as the Mechanism, Meron had assumed responsibility for all

international prisoners' supervision. Meron was now in charge of making new

rules and judgments upon these cases. A Polish-born US citizen and an

international lawyer with a stellar career, Meron was a French Légion d’Honneur and a Shakespeare scholar. The first president of

the Mechanism, Meron, served from its creation in 2012 until January 2019.

The Security Council

established the Mechanism to complete two international criminal tribunals'

work when they closed – the ICTR and its forerunner, the International Criminal

Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).63 A part of the Mechanism mandate was

to supervise those convicted of grave violations of international humanitarian

law in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia.

Meron had served on

the Appeals Chamber used by both the ICTY and the ICTR. He was widely

considered one of the world’s most distinguished specialists in international

human rights law and international penal law; his numerous books and articles

contributing to the advance and development of the discipline, and he advised

the US government and State Department. In his job as president of the

Mechanism, Meron maintained high-level contacts with the governments of UN

member states to facilitate and improve cooperation with the Mechanism: he was

required to make annual reports to the General Assembly and biannual reports to

the Security Council.64

With Meron as

president of the Mechanism, the prospects of the imprisoned Rwandan génocidaires improved considerably. Meron took advantage of

his powers as president to alter the internal procedures already in place. He

used a device known as ‘practice directions’ to adopt new rules for the method

for determining applications for pardon, commutation of sentence, and early

release of persons convicted by the ICTR, the ICTY, or the Mechanism (PDER).

Meron, the only full-time judge on the Mechanism, ensured his new rules by a

plenary of judges via remote communication in June 2012.

His changes had

significant results.65 Meron was no longer required to make public his

decisions on early release and now consider humanitarian and health issues. He

was no longer needed to consult survivors nor to ask the original trial judges

for an opinion. However, when the Security Council created the ICTR, the

enabling resolution mandated that there must be consultation with trial judges

in early-release cases.66 This was also a requirement written into the statute

of the ICTR.67 Although the enactment of the Mechanism did not refer to

consultation with trial judges, its rules and practice specified that the

president should consult with any judges of the sentencing chamber, but only

those who continued to serve as judges on the Mechanism.68 This provision

disappeared, and by 2016, when the time came to release Ferdinand Nahimana,

Judge Meron was no longer required to consult any judges at all. One legal

scholar noted drily, ‘Perhaps release is considered to be an administrative or

executive task at the MICT (Mechanism), but this should not preclude judicial

review of decisions.’69 Another factor that significantly improved the

prospects of the génocidaires was the decision made

by Judge Meron to apply the same rules to the Rwandan prisoners as those that

governed the imprisonment of those responsible for war crimes in the former

Yugoslavia. There was a need for ‘equality among international prisoners, irrespective

of the court that sentenced them.’70 At the ICTY, convicted prisoners, were

eligible for release after they had served two-thirds of their sentences.

Henceforth, the two-thirds eligibility rule applied to the entire prisoner

population over which he, as president of the Mechanism, supervised. While

conceding, this could ‘constitute a benefit for the Rwandan prisoners,’ he

wrote, ‘this alone could not justify discrimination between the groups of

convicted persons under the jurisdiction of the Mechanism.’

When in October 1994,

informal negotiations had taken place in the Security Council to discuss the

establishment of a criminal tribunal, the Rwandan ambassador who was

representing the new government established in Kigali wanted those convicted by

the tribunal to serve their sentences in Rwanda. He sought a voice for the

Rwandan government on any pardon or commutation of sentence and warned that the

members of the former Hutu Power government might ‘be sent to serve their time

in France and would be able to wangle their way out of jail early.’71

It did not turn out

this way. Only in June 2018, and facing criticism for the first time in his six

years as president of the Mechanism, did Judge Theodor Meron consult the

Rwandan government about the next three proposed early releases. Rwanda’s

justice minister, Johnston Busingye, wrote directly to Meron to object in the

strongest terms to any further statements. The severity and gravity of the

crimes should be sufficient to deny the prisoners’ applications.72 ‘Nothing

about these people has changed,’ he said. ‘They have shown no remorse, not even

acknowledgment of their crimes.’ There were objections elsewhere, and Toby

Cadman, the co-founder of a human rights organization in London, Guernica 37

International Justice Chambers, thought that early release of anyone convicted

of genocide served only to undermine the process of international law.73

One of the three

prisoners under consideration was journalist Hassan Ngeze,

the editor of Kangura, convicted in the media trial

at the ICTR of genocide and public incitement to commit genocide. Like

Ferdinand Nahimana in the same trial, the Appeals Chamber had reduced Ngeze’s life sentence to thirty years. One of the media

trial lawyers, the prosecutor Simone Monasebian, on

hearing of the possibility of Ngeze’s release, wrote

to Meron. She explained that Kangura and radio RTLM

had fuelled the genocide, and both had been more

potent and dangerous than bullets or machetes. The génocidaires

were unrepentant violent extremists, she told him.

The survivors’

organization Ibuka announced that Meron was the ‘epitome of all things wrong

following the aftermath of the 1994 genocide’. The organization had repeatedly

called for an investigation of every controversial decision taken by Meron,

either reduction in sentence or early release. Any decision that served to

benefit genocide perpetrators also helped their campaign of denial. Every

decision that diminished the status of the crime of genocide needed

investigation.74

There were several

cases worth consideration. Meron was the presiding judge of five justices on

the appeal that reduced the life sentences of Colonel Théoneste

Bagosora and Colonel Anatole Nsengiyumva, both