By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Taiwan President Tsai

Ing-wen won re-election by a historic landslide on Saturday, a decisive result widely

seen as a rebuke to Beijing’s efforts to gain control over the island

democracy.

Since 2016, Beijing

has stepped up its diplomatic isolation of Taiwan. Since Tsai took office,

Taipei has lost seven (see chart below) diplomatic partners. Only 15 small

countries currently have official diplomatic relations with Taiwan. However,

Taiwan maintains informal relations and bilateral partnerships with countries

around the world. The United States, for example, is Tapei's most important strategic partner.

Remaining vigilant,

in her victory speech, Tsai told China to abandon its threat to take back the

island by force, and that: "Taiwan is showing the world how much we

cherish our free democratic way of life and how much we cherish our

nation."

Beijing instead

considers the Chinese-speaking democracy to be a renegade province of China.

Ever since Taiwan split from the mainland in 1949, Beijing has clamored for

unification with the self-governing island, by force if necessary, and pushed

it to adopt the "one China, two systems" self-rule arrangement it

employs in Hong Kong and. Tsai’s victory highlighted how successfully her

campaign had tapped into an electorate that is increasingly wary of China’s

intentions.

A Chinese Foreign

Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang was quick to reiterate that no matter what

happens in Taiwan, the fact that

there is only one China in the world and Taiwan is part of China will not

change, said the spokesperson. The China Morning Post wrote that Taiwan may

face

retaliation and tactics that could include military intimidation or trying

to convince Taipei’s remaining 17 diplomatic allies to switch their ties to

Beijing.

This whereby

supporters of Tsai 's stance argue that Taiwan can live with losing small

diplomatic allies, many of them dependent on foreign aid and investment, as

long as it strengthens unofficial ties with major democratic powers, like the

U.S. and Japan.

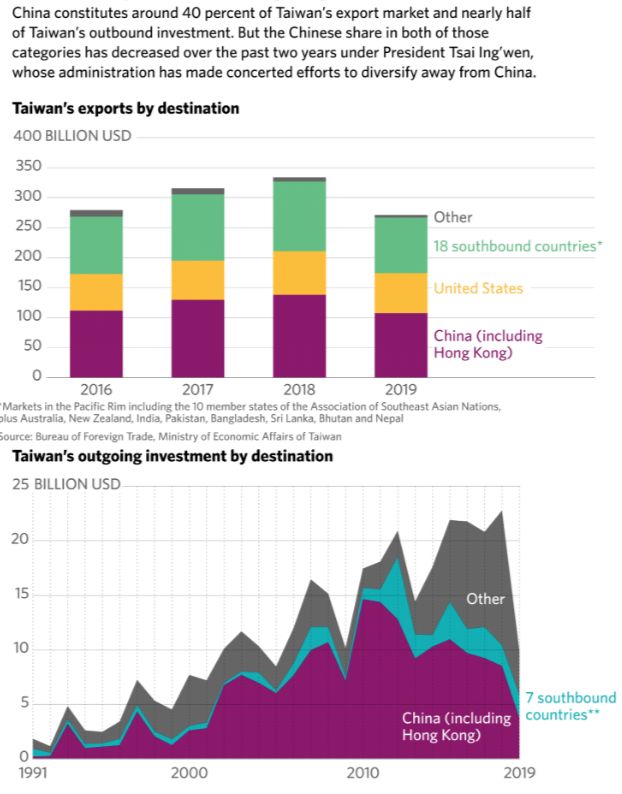

It also should be

noticed that the Taiwanese economy is intertwined with China, hence, contrary

to younger voters, many of the older people who voted for Tsay rather prefer no

major changes to the present status quo.

Jonathan Sullivan, a

Taiwan expert at the University of Nottingham, said that “In general terms,

neither side wants a confrontation over Taiwan, and certainly the US is

thankful that Tsai has not rocked the boat, a careful posture I expect her to

continue,” he said. “The wild card is Beijing, which has painted itself into a

corner with regards to Taiwan. There just isn’t room for them to concede the

bit of space Tsai needs to start talking again.”

Taking a different

approach Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project at the

Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, predicted that

Tsai’s big win could prompt Beijing to change its strategy. “Chinese policies

are not succeeding in promoting closer ties, and Tsai’s landslide victory may

cause China to rethink its approach,” she said.

The consequences

Taiwan’s President

Tsai Ing-wen's last night's landslide victory in elections will extend her term

by four years, setting the island nation on a course for an extended period of

cross-strait tensions with mainland China if, as expected, Beijing maintains

its hardline approach to her administration. Tsai's ruling party also captured

a majority in Taiwan's 113-member parliament. The strength of her victory

raises questions about how China will choose to deal with her administration

while strengthening U.S. options for countering Chinese influence. The Chinese

government could now be forced to rethink its completely restrictive policies

to take into account the rise of more radical pro-independence factions inside

the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and a long-term shift in Taiwan’s

political landscape.

Why it matters

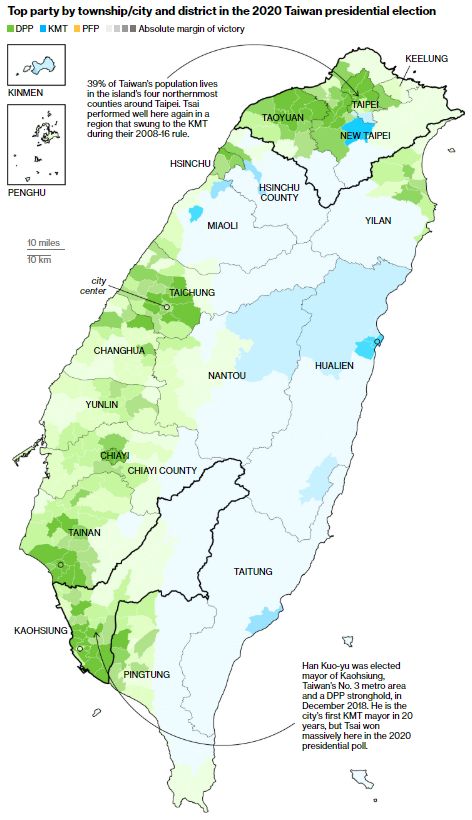

Tsai secured more

than 8 million votes among some 14 million Taiwanese voters, a record margin of

victory since direct presidential elections began in 1996, and outpaced her

main challenger, Han Kuo-yu from Kuomintang, by 2.5

million votes. Concurrently, the DPP is also set to retain its majority in the

113-member Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s parliament, even though it lost control

of seven more seats than it currently has. The opposition Kuomintang gained

three more than its previous total. Minor parties that play a third force in

the island’s traditionally bipartisan political landscape made some limited

strides in these elections. Turnout also reached a record high of 74.9 percent,

reflecting high political awareness among the electorate. In light of her party's

slightly less impressive legislative performance than in past elections, Tsai's

landslide win indicated that her approach to relations with Beijing was popular

enough to overcome discontent among the electorate over some of the DPP’s

domestic policies. Against the backdrop of Hong Kong's pro-democracy protests

and perceived political interference from Beijing, the result reveals growing

resistance among Taiwan's residents to Chinese influence, a feeling only set to

grow stronger as the island's younger generation rises.

The larger context

For one there no

single iteration of the ‘One China Principle’, but a series of different

versions and refinements. In essence, all subsequent versions grew from the

rapprochement between the US and the PRC in the 1970s, and were created from

the need for there to be a policy framework of sorts in a place where America

could develop its new links with Beijing, but maintain what it felt were its

responsibilities to the ROC. An uncharitable interpretation of this would be

that ‘One China’ was the US’s way of trying to salve its conscience and walk

away from an alliance with Taiwan, while still being able to say it had done

the right thing. In many ways, therefore, it was America, rather than the PRC,

that asked for the policy to be stated the way it is, and that to this day

lives with the consequences.

As explained earlier, after the end of WWII, the Communist

Party of China (CPC) under Mao Zedong pursued a fierce battle against his

archrival Chiang Kai-shek, chief of the Kuomintang (KMT) party. Chiang lost and

took refuge on the island of Taiwan. For some time after that, Taiwan was the

center of propaganda from both sides. The CPC wanted to "liberate"

Taiwan, while Kuomintang wanted to "recapture the mainland."

Successive Chinese leaders have made unification a top foreign policy goal.

Starting in the

1990s, Taiwan’s democratization and its growing political and cultural distance

from the mainland made China’s objective harder and harder to achieve.

Beijing’s efforts to pull Taiwan closer into its orbit, including by meddling

in the island’s elections, have met with limited success.

In fact while the

effect of Beijing’s influence operations on the campaign was difficult to

measure, it certainly was there, for example in 2008, the pro-Beijing chairman

of Want Want China Holdings purchased

one of Taiwan’s largest media groups, the China Times Media Group. The group

was Taiwan’s fourth-biggest media conglomerate and consisted of three daily

newspapers, three magazines, three TV channels, and eight news websites. In a

company newsletter, the new owner said he would “use the power of the press to

advance relations between China and Taiwan.” He has also publicly endorsed

Taiwan’s unification with China.

Taiwan’s officials and

media watchdogs were also reporting

a deluge of disinformation on social media apps and websites. Often, as the

analyst J. Michael Cole has observed, the messages seem intended not only to

boost candidates but to amplify social divisions and sow confusion and

doubt about the state of Taiwan’s economy and the performance of its

government including put pressure on smaller nations to cut diplomatic

relations with Taiwan.

This should not

denigrate the immense strategic importance of the Taiwanese islands. They sit

in one of the world’s great seaways, a place

which, as the economies of Japan, South Korea, Malaysia and then China and Hong

Kong have grown around them, has become increasingly important.

The earliest

inhabitants of this space were not Chinese. They originated from elsewhere,

part of the Austronesian group that now has populations in the Philippines,

Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and embraces the Maori

population as far afield as New Zealand.

Until the first

significant settlements in the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1367– 1644) of those from

the Mainland, historic Formosa was dominated by the ancestors from this

Austronesian group. After the migrations from Ming China, the destiny and

identity of the island gradually changed. But that doesn’t alter the fact that

its involvement in the history of the Mainland is a recent phenomenon. There

was no Tang Taiwan in the 7th to the 10th century, or Song or Yuan Taiwan from

the 10th to the 14th, key dynasties on the Mainland. Even for the Ming and

Qing, Taiwan's history is complicated and does not follow a neat linear thread.

In an address marking

the 108th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of China, Taiwan’s

official name, on October 10, Taiwan’s now re-elected President Tsai Ing-wen

denounced China for its efforts to force Taiwan into unification talks under

the “one country, two systems” model. She said the framework is failing Hong

Kong, and that the protection of Taiwan’s sovereignty is not provocation, but

her responsibility. Conspicuously missing from the celebration also was the

history of the Republic of China, a title used by the island’s authorities

since Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist, or Kuomintang, forces retreated to the

island in 1949 and set up an interim government following their defeat in the

civil war. What next with Taiwan.

Child of the

Westphalian Treaty from the European 17th century, while the notion of

statehood has undergone modification under post-modernity, in Asia the idea is

alive and well and sits at the root or the cross-Strait issue. In Chinese

pasts, there were, as alluded to before, very different notions of what it was

to be a political entity, leading to ideas of suzerainty and the notion of ‘all

under heaven’ with its tributary system. These have left a memory trace which

continues to create issues today, in places like Tibet. There was no neat

sovereign entity called China until very recent history. Nor was there a place

with a firm idea of what its international status was, and what its set borders

or rules-based diplomatic relations might be. Under a similarly flexible

system, perhaps the Taiwanese issue would have been long solved.

Going forward

For the Taiwanese, Hong Kong stands as a stark warning that the

vague promises of Beijing and the grand informal structures it might promise to

put in place, should any reunification deal be discussed, are undercut by a

hard political reality which can never be expressed but will always be there.

This is that Beijing always has the final say.

With Tsai's party

having won Beijing may be forced to consider moderating its current hard-line stance in order to insulate the more radical

wings in Taipei. The need for foreign investment, as well as the desire to

maintain Taiwan's economic reliance, may also compel Beijing to create new

incentives to draw in more Taiwanese business to the mainland.

But China will firmly

protect its territorial integrity and opposes any separatist attempts and

Taiwan independence, its Taiwan Affairs Office spokesman said on Saturday,

after the

re-election victory of the self-ruled island's leader Tsai Ing-wen.

And as a commentator

for the Singaporean New Straights Times wrote:

Chinese President Xi Jinping is likely to continue

with his current policy and even tighten it.

Pressuring Tsai also

serves to demonstrate Beijing’s consistency and determination to maintain

political cohesion and ideological resolve, especially in times of external

pressure, much owing

to the paranoia that China could follow in the footsteps of the Soviet

collapse.

Thus Beijing is still

most likely to maintain or even double down on its hardline policies against

Taipei. This, of course, will come at the risk of escalating tensions with the

island and could even create a Hong Kong-like confrontation. Thus future cross-strait

relations will be intertwined closely with the context of China's economic

slowdown and intensifying competition with the United States, as well as the

rise of Taiwan's nationalistic sentiment.

Taiwan’s status thus

seems to offer almost intractable quandaries and problems. ‘One China’ which

has to exist as two remains a conundrum that once anyone attends to it becomes

simply insoluble because it doesn’t make sense.

Taiwanese journalist

Yang Chien-Hao said that in general people in Taiwan are not too worried about

the mainland’s possible military invasion of the island as the cost for Beijing

to do so would be very high if the United States, or even Japan, intervened.

Yang said that since Tsai took office in 2016, a lot of overseas Taiwanese

businessmen had returned to Taiwan as they were not afraid of worsening

cross-strait relations.

Since its transition

to full democracy beginning in the 1980s, Taiwan indeed has increasingly

asserted its independent identity from China even though it is not recognized

by the United Nations and only by a fraction of its members. And while many

cultural traditions of the Chinese mainland are still alive and well preserved,

Taiwanese society has evolved into its own society. Thus there is sufficient

evidence that Taiwan can be considered an independent state.

But not only is

Taiwan a proxy for much of the world’s strategy to deal with the consequences

of an increasingly authoritarian China Taiwan is also trying to manage its

economic relations with China.

The fact that Taiwan

offers an alternative model of Chinese modernity is one that carries deep

challenges, and often real threats to Beijing. That is the trouble with Taiwan.

And, through the immense importance of this region for the rest of the world, that

is why this problem is not just a local, but a global one.

For updates click homepage here