By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

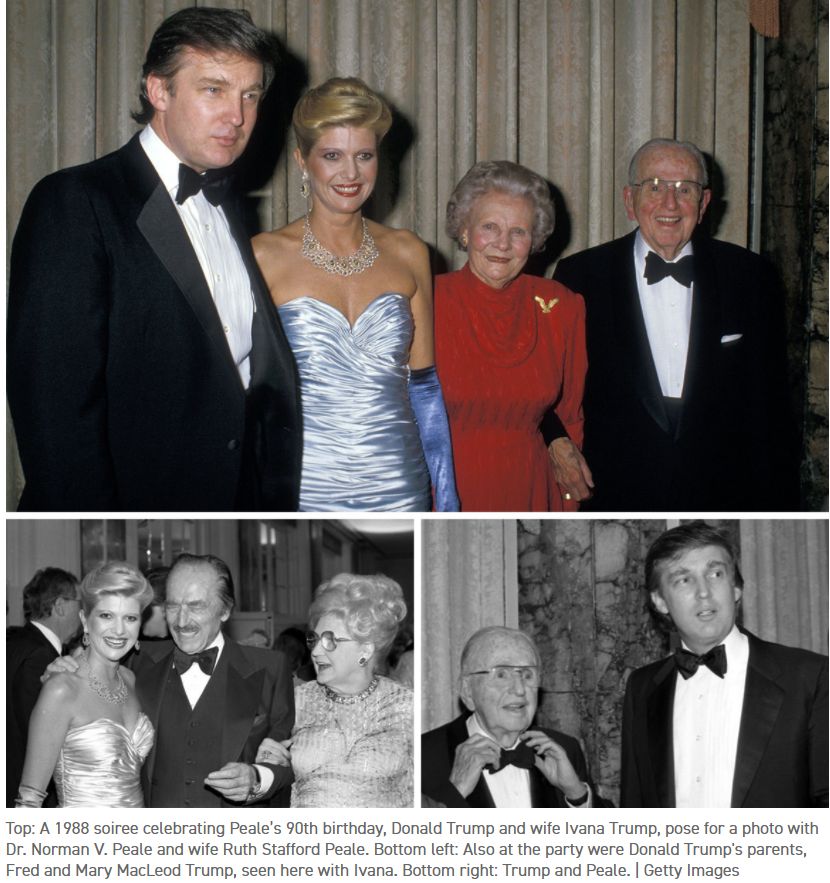

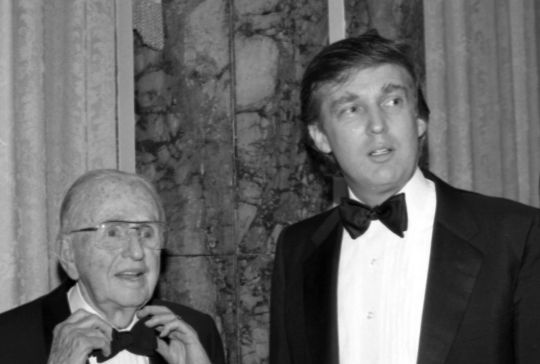

President Trump And The US Positive Thinking Movement

Throughout the late

19th and early 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of Americans scooped up

dozens of titles promoting the New Thought ethos: If you feel it, it will come

true. There was Charles Benjamin Newcomb’s 1897 “All’s Right With the World,” which

instructed readers not to wish for betterment but to summon it through force of

will. (“I am well.” “I am opulent.” “I have everything.” I do right.” “I

know.”) There was William Walter Atkinson’s 1901 “Thought-Force in Business and

Everyday Life.” (“Anything is yours, if you only want it hard enough. Just

think of it. ANYTHING. Try it. Try it in earnest and you will succeed. It is

the operation of a mighty Law.”) Capitalists like Napoleon Hill advised readers

to “Think and Grow Rich” (1937). And Christians, including Quimby’s onetime

patient Mary Baker Eddy, sought to blend that faith with New Thought practice,

as Eddy did in establishing Christian Science.

Similar with Vincent

Peale. Positive thinking, he argued, didn’t need to be constrained by reality.

Rather, Peale told

his readers to “make a true estimate of your own ability, then raise it 10 percent.”

But since few are familiar with the history of Vincent Peale's new thought we

went about to trace it to its beginnings.

"Confident

living rights every wrong; / Dynamic power helps me be strong. / Confident

living comforts my heart; / From such a blessing I can't depart."

"Confident living fulfills my way, / Opens my channels without

delay." So runs the refrain and part of one verse of a favorite hymn in

Unity churches. Others like groups-Divine Science, Religious Science, and

Unity-all thrived through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first,

bringing their versions of "It is done unto you as you

believe"-confident living, to pragmatically tuned metaphysical believers

and practitioners.

A strong example of

the facile networking that characterized New Thought from its beginnings,

Divine Science could boast a series of founders-the three Coloradobased

Brooks sisters, Alethea Brooks Small, Fannie Brooks James, and, foremost, Nona

Lovell Brooks (1862-1945), as well as Malinda Cramer (1844-1906), who gave the

movement its name. In 1885 in San Francisco, Cramer, who had been an invalid

for twenty-five years, gave up on doctors and determined to get well on her

own. After that, according to her own report, she had a felt experience of the

omnipresence of God and experienced, too, a sense that she herself was in God.

She got well and by 1887 began teaching and also attended a class offered by

Emma Curtis Hopkins in the Bay City. Cramer had likewise formed an association

with a former Mary Baker Eddy student named Miranda Rice, so she must have been

aware of Eddy's teaching.

The same year that

Cramer took the Hopkins class, in Pueblo, Colorado, two of the Brooks

sisters-Nona and Alethea-became students of Kate Bingham, a teacher who had

returned from Chicago, where, she claimed, she had been healed by Hopkins.

Bingham's classes, too (and not surprisingly in light of the Hopkins

connection), stressed the omnipresence of God. Nona Brooks, who had a troubling

throat condition unresponsive to medical treatment, took the Bingham classes

and in the course of one of them claimed an experience of white light and sheer

presence that left her instantly and completely healed. Meanwhile, the third

sister, Fannie Brooks James, studied under Mabel MacCoy, a former Chicago

Hopkins student who had first sent Bingham to her teacher there. Immersed in

Hopkins teaching and teachers, the three at the same time moved away from the

denials of the reality of the material order characteristic of Christian

Science and Hopkins-style New Thought, affirming the creation as an expression

of God that shared in the divine substance. When Cramer traveled to Denver to

teach New Thought classes, Nona Brooks attended, and the two women felt a

connection. The name Divine Science came from Cramer, and the Brooks sisters

received permission to use it for their teaching. The two streams converged. To

the Statement of Being found in one form or another in both Christian Science

and New Thought groups (there is no reality but God), Divine Science added the

Law of Expression - an agency-oriented formula that stressed the act of the

creator as manifested in creation. The shift was subtle, but it suggests once

again the preoccupation with energy that Trine had signaled and that marked the

twentieth-century-and-continuing version of metaphysics so strongly.

In 1892, Nona Brooks

formed the International Divine Science Federation, and in 1898 the Divine

Science College was incorporated in Denver. With networking intrinsic to its

style and with Brooks a prominent speaker at New Thought conventions, by 1922

Divine Science had become part of the International New Thought Alliance. By

then, too, its churches were flourishing in West Coast cities and also in

midwestern locations like Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, and Ohio, while, in the

East, Boston, New York, and Washington, D.G, all became sites for Divine

Science churches. The relatively independent congregations in the movement

became more formally organized in 1957 with the creation of the Divine Science

Federation International. Meanwhile, Divine Science publications kept coming.

In former Irish Catholic and Jesuit-trained Emmet Fox (1886-1951), with his

metaphysical readings of the Bible and his "Golden Key" of reflecting

on God instead of present difficulty, the movement produced one of the most well-known

New Thought authors of the Depression years.

By contrast to Divine

Science, the roots of Religious Science lay in the experience and teaching of

one man. Ernest Holmes (1887-1960), however, in his combinativeness

thoroughly reflected the New Thought desire for synthesis that Divine Science

also hinted. Holmes, like a series of metaphysical religious leaders before

him, did not come to his task equipped with professional training. He never

went to college, although his brother Fenwicke Holmes graduated from Colby

College in Maine, went on to Hartford Theological Seminary, and became a

Congregationalist minister on the West Coast. Fenwicke Holmes, however, would

eventually leave the ministry to work with his brother, and it was Ernest

Holmes who took the lead in the movement that became Religious Science.

Important here, from early on he was apparently an insatiable reader. J.

Stillson Judah detailed a series of authors whom Holmes knew, including Emerson

and especially his classic essay "Self-Reliance." The future

Religious Science founder was familiar with Eddy's Science and Health, had read

New Thought authors like the affective Hopkins and Cady and the more noetic

Christopher D. Larson and Orison Swett Marden, and was drawn as well to the

"Hindu" mysticism of Swami Ramacharaka. By 1915, he had turned his attention to

Hermetic materials, the Bhagavad Gita, and even the Persian Zend-Avesta. He was

also seeking to synthesize these widely different materials with an AngloAmerican literary tradition of reflection that

included Emerson, Walt Whitman, William Wordsworth, and Robert Browning. Most

of all, he found himself attracted to the English metaphysical writer Thomas Troward (1847-1916), with his triadic understanding of body

conscious mind, and spirit as the stuff of human existence. For Troward and for Holmes, spirit represented both the

Universal Mind (God) and the subjective, or unconscious, the mind of humans.

This subjective mind mediated God's creative power, and it responded to

suggestions from the conscious mind to manifest health or illness. Indeed,

there was a mechanical quality to the divine operation in this activity, since

Universal Mind produced a form in the objective world to match each idea - in Troward's conscious application of what he saw as the

Swedenborgian law of correspondences.1

A concise history of origin and development of the New

Thought movement

The coming of Norman Vincent Peale and Trump

Around the same

time American Spiritualism was born,

Mary Baker Glover's crisply titled Science and Health appeared in print.2 A

work of over 450 pages, it was the culmination of a decade of metaphysical

reflection and writing by a woman in her mid-fifties who counted herself

thoroughly Christian. Indeed, she wrote it after she claimed a spiritual

discovery that would radically reorient religion and spiritual practice for the

Christian churches. Known more familiarly as Mary Baker Eddy (1821-191O)-the

name she assumed after her marriage to Asa Gilbert Eddy in 1877-the author

brought far less cosmopolitanism than did Olcott to a work that would go

through a plethora of editions until the familiar 1906 version became the

standard text.3 Science and Health stood beside the Bible for Christian Scientists,

and it became the scripture that was canonically read in Christian Science

services everywhere. Eddy herself would look back on the work in her later

years in ways that hinted of the kind of "channeled" text that

numerous spiritualists, as well as Helena P. Blavatsky, claimed to produce.

When Eddy wrote it, she declared, she had "consulted no other authors and

read no other book but the Bible for three years." Still more, as she

said, "it was not myself, but the power of Truth and love, infinitely

above me, which dictated 'Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.”4

lf

Eddy had begun Christian Science in mid-life, she continued to preside over the

fortunes of her religious foundation with a success that could be estimated by

the imposing Boston Mother Church dedicated at the end of 1894. These times of

abundance and fulfillment, however, had been preceded by a personal life more

bleak and compromised. Born in Bow, New Hampshire, Mary Morse Baker had grown

up in the shadow of the Congregational church with its Puritan past and was

formally admitted to membership at twelve, even though she could not affirm her

pastor's old-school doctrine of predestination. She would continue to affirm

her connection to this Congregational world, and, in fact, the language of sin

was woven in and out of her writings throughout her life. Arguably, she never

gave up Calvinism when she embraced metaphysics. As earlier proto-metaphysical

and metaphysical practice already demonstrates, commitments to mind and

correspondence could encompass Christian categories. Now, in what would become

Baker Eddy's Christian Science, we test the limits of such combinativeness.

A youthful Baker

married Colonel George Washington Glover of Charleston, South Carolina, in

1843, lived with him in the South for a year, and then, when he succumbed to

yellow fever, returned to New England and gave birth to a son. Glover was

chronically ill, and her family was, for various reasons, unsupportive in

helping to care for the boisterous child. When he was five-after her recently

widowed father remarried-the little boy, George Jr., was sent away to live with

a now-married former family servant with whom Glover herself had a warm

relationship. She apparently agreed to the plan reluctantly. Her second

marriage, with the philandering dentist Daniel Patterson, ended in divorce in

1873, but she had gone back to the surname Glover well before that.5

Hard times dogged

Eddy (to use the familiar surname) as she moved from one shabby boardinghouse

to the next, living with people below her social station because of the paucity

of her means. Here she experienced the spiritual seeker culture of her age in a

readily available world of mesmerism and spiritualism. Meanwhile, she continued

to be plagued with ill health-probably mostly what George Beard would by the

1880s label "American nervousness," or neurasthenia.6 Eddy's physical

complaints brought her to homeopathy, hydropathy (water cure), and mesmerism

and eventually to the reformed magnetic medicine of Phineas Parkhurst Quimby

(1802-1866), a well-known mental healer practicing in Portland, Maine. The

teaching and practice of Quimby, placed beside the authoritative message of Congregatjonal Calvinism, became a major influence that

helped to catalyze Eddy's own combinative system in Christian Science after his

death in 1866.

One of the marquis de

Puysegur's pupils, Charles Poyen, established an

itinerant mesmerist practice in New England. Poyen remained in North America

until 1840, and taught literally hundreds of people the techniques of

mesmerism. Some American mesmerists followed paths reminiscent of the German

proto-spiritualists. Thus, among the starting points of spiritualism sensu

stricto were the Swedenborgian spirit messages received in the 1840s by the

American cobbler Andrew Jackson Davies when under mesmeric trance. Others

developed mesmerism into a uniquely American family of religious traditions.

Quimby one of Poyen's many apprentices eschewed the ballast of metaphysical and

cosmological speculation that had been part and parcel of much European

mesmerism. He expressed his theories in a vague theistic language, religious

enough to be acceptable to a churched country such as the USA, yet not specific

enough in doctrinal contents to offend the members of any particular creed.

Quimby took a practice that reeked of mysticism and transformed it into an

eminently practical recipe for health, happiness and prosperity. The reason for

such a radical change in mesmerism could be sought in the particular

individualism of early nineteenth century American society, a mode of thinking

and living that not only reworked an esoteric praxis into a recipe for living,

but also remolded Old World Protestantism into prosperity thinking and Oriental

philosophies into transcendentalism.

A number of Quimby's

former patients founded their own religious movements, collectively known as harmonial religions. They fall into two broad categories,

Christian Science on the one hand and the various New Thought denominations on

the other. If Quimby was only vaguely theistic, the harmonial

religions were all the more inspired by Scripture. In several harmonial religions, and especially in Christian Science,

the roots in American mesmerism are all but hidden under a christianized

theology, based on scriptural interpretation. Harmonial

religions, although of great intrinsic interest, fall outside the scope of the

present study, except in one important respect. Throughout the development of

post-theosophical esotericism, rituals and doctrines with roots in American harmonial religion have been reincorporated into a more

explicitly Esoteric framework. Books by late twentieth-century writers such as

Wayne Dyer, Deepak Chopra and Shakti Gawain as well as the channeled A Course

in Miracles are among the true bestsellers of the New Age movement. They employ

discursive strategies foreign to most harmonial

religions which, generally speaking, attempted to find a scriptural rationale

for their doctrines. Nevertheless, the doctrines themselves all lean heavily on

elements borrowed from the harmonial religions.

Eddy worked with

Quimby not merely as a patient-for whom the "medicine" was in large

part effective - but also as a student transcribing notes of conversations with

him, reading his own notes and sometimes "correcting" them, and acting

increasingly as an intellectual colleague to her mentor. Moreover, as a Quimby

patient-student, Eddy was hardly alone. Among the others who participated in

the loose Quimby community were major early leaders in the New Thought

movement. Remembering the well-known mental healer's relationship with the

others, his son George Quimby recalled that his father would "talk hours

and hours, week in and week out ... listening and asking questions. After these

talks he would put on paper in the shape of an essay or conversation what

subject his talk had covered." Eddy, as George Quimby wrote, actively

participated, even as she pursued a one-on-one intellectual relationship with

the doctor, and her own thinking apparently intermingled with his.7

Who was this Portland

healer whose thriving practice had attracted Eddy, the ailing neurasthenic

patient, and who became a major intellectual and spiritual influence on her

life? An autodidact like Eddy herself, Quimby was making clocks in Belfast,

Maine, when he attended the above mentioned, Charles Poyen's lectures in 1838.

Attracted to the

medical applications of animal magnetism, he partnered with the youthful Lucius

Burkmar in an itinerating stage demonstration of

clairvoyance in healing. In performances that took place as the pair traveled

the lyceum circuit, Quimby mesmerized Burkmar, Burkmar "read" the disease that afflicted an

inquiring audience member, and then Burkmar

prescribed the remedy that would heal the illness. As the process worked - even

on Quimby himself-he raised critical questions about it and eventually became

convinced that the true agent of healing success was the power of suggestion

and the belief it fostered within each subject. Quimby had arrived, in an

incipient way, at the notion of the power of mind. In the process, he also

became confident that he, too, possessed clairvoyant powers. Subsequently

parting ways with Burkmar, he began a practice that

increasingly departed from its magnetic beginnings with compelling religious

and theological questions Robert Peel noted that he attended Unitarian and Universalist

churches.8

And Quimby surely

knew the Bible, as his writings reveal. Meanwhile, his religious liberalism

links him to the harmonial philosophy of Andrew

Jackson Davis and other spiritualists, and some of his ideas can also be linked

to those of Emanuel Swedenborg and of the American Transcendentalists. In the

American culture of Quimby's era, as we have already seen, mesmerism blended

with spiritualism into a viable way to think and act, to make sense of basic

problems of human life in a kind of armchair philosophy that was also a

pragmatic set of principles for action. Quimby's writings, rough and opaque

though they often are, record his perceptions of this nineteenth-century

thought world as he constructed his own. Whatever his knowledge of Davis (and

there is no evidence, of which I am aware, that he ever directly read the

well-known spiritualist), Quimby was intimately acquainted with spiritualism in

its phenomenal form. Ervin Seale's complete edition of Quimby's writings,

published only as recently as 1988, makes Quimby's familiarity with a

spiritualist discourse community abundantly clear. (Seale's work overturned the

partial, sanitized 1921 edition by Horatio Dresser-son of New Thought leaders

Julius and Annetta Dresserwhich left out Quimby's

spiritualism and idealized his materialism.)9

The man who emerges

from the Seale edition attended seances frequently and could influence the

phenomena that occurred in the circles. "I profess to be a medium myself

and am admitted to be so by the spiritualists themselves," he owned in one

essay and, in another, related an account of a seance at which he proved

himself to be a "healing medium." He had become a medium, he claimed,

but-like the Blavatsky of a decade or more later-he enjoyed a freedom not

experienced by others. "I retained my own consciousness and at the same

time took the feelings of my patient," he declared.62 Yet this Quimby-on

such close terms with spiritualists and their seances and so thoroughly

familiar, too, with the details of mesmeric practice-admitted the phenomena

but, again like Blavatsky, thoroughly disputed their cause and conditions. For

him, however, what generated mesmeric success and spiritualist manifestation

were not "elementals" or "elementaries" but simple human

belief and opinion.

Mesmerism and

spiritualism were "phenomena without any wisdom," and a spirit was

"the shadow of a person's belief or imagination." A person could not

"give a fair account of the phenomena of Spiritualism" because the

"experiments" were "governed by ... belief and must be so."

Quimby wasted no words in pronouncing "ghosts and spirits" to be

"the invention of man's superstition." "So long as people think

about the dead," he stated flatly, "so long there will be spirits,

for thought is spirit, and that is all the spirits there are." How did the

production of spirits work, and what was the mechanism of spiritualist

activity? Quimby's answer lay in the generic "power of creating ideas and

making them so dense that they could be seen by a subject that was

mesmerized." This was the state that; in his single-source explanation,

embraced "all the phenomena of spiritualism, disease, religion and

everything that affect [ ed] the mind." Nor did mesmerism and spiritualism

essentially differ. "The word 'mesmerism,'" Quimby wrote,

"embraces all the phenomena that ever were claimed by any intelligent

spiritualists." Clearly, the "other world" was "in the

mind." "The idea that any physical demonstration" came

"from the dead" was to him "totally absurd." 10

Still, Quimby had

bought into the spiritualist universe enough to reiterate the materialist

explanation for mesmeric and similar phenomena that had been popularized by

Davis and others. "Spirit" was "only matter in a rarefied form,

and thought, reason and knowledge" were "the same."

"Mind" was "the name of a spiritual substance that can be

changed" and was, in fact, "spiritual matter."

"Thought" was "also matter, but not the same matter;' just as

the earth was not "the same matter as the seed which is put into it."

Moreover, Quimby echoed the spiritualist seer in further ways. J. Stillson

Judah decades ago pointed to parallels between Davis's and Quimby's etiology of

disease in the discords of the human spirit and their perception of an

"atmosphere" surrounding a human subject that could be affected, for

good or ill, by another. He noticed, too, their mutual identification of God

with Wisdom and a series of other similar (often Swedenborgian and Hermetic)

beliefs regarding divine and human nature and human destiny.11

Regarding

"spiritual matter;' so pervasive was Quimby's identification between

cognitive phenomena and the material realm that it is easy to read him as a

thoroughgoing materialist, given his immersion in the language world of

mesmerism and spiritualism. Yet this conclusion fails to notice the rather bold

departure that Quimby made from mesmeric-spiritualist canons and ideas-a

departure that his patient-student Mary Baker Eddy was to take and transform in

terms of Calvinist Christianity to create Christian Science. In Quimby's

reconstruction of the received cosmology, he combined the materialism of his

sources with an idealism that at least one mid-twentieth-century scholar linked

to Transcendentalism. Quimby's knowledge of the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson and

other Transcendentalists was no doubt tenuous and secondhand at best, but major

newspapers habitually summarized Emerson's lyceum lectures, and idealist views

were clearly there for the taking.65 Beyond that, a generalized Swedenborgianism could be argued in tandem with these

ideas. Judah, for example, pointed to the essentially Swedenborgian views that

Quimby held regarding what he termed the "natural" and the

"spiritual man," and his preference for an analogical, or

allegorical, reading of scripture in the tradition of Swedenborg.12

Whatever Quimby's

sources, his writings demonstrate though going preoccupation with a wisdom that

transcended the material world of mind and mesmeric play. Alternately cast,

this wisdom operated as a metaphysical "solid" that suffused the

world, like a ghost of the mesmeric fluidic ether but always elusively

nonmaterial. Set in this cosmological situation, two kinds of humans inhabited

the earth-the "natural man," caught in the error of a materialist

mind and its attendant phenomena, and the "scientific man," who saw

past the performance into the space of wisdom. Quimby argued for the wisdom

world: Calling the power that governed the material mind "spirit,"

the Portland physician yet recognized "a Wisdom superior to the word mind,

for I always apply the word mind to matter but never apply it to the First

Cause."13

Still more, although

Quimby was thoroughly anticlerical and opposed to orthodox Christianity, his

familiarity with Christian scripture meant that his writings were filled with metaphysicalized biblical references to contend for his

view. Indeed, in his private papers, he betrayed a kind of messianism in which

he identified himself with the biblical Christ, at the same time typically

separating Christ, as identical to Science, from sole attachment to the

historical Jesus. "Jesus never tried to teach anything different from what

I am teaching and doing every day," he testified. His statement of his own

case is crucial for understanding the new production that became Eddy's

Christian Science: "Now I stand as one that has risen from the dead or

error into the light of truth, not that the dead or my error has risen with me,

but I have shaken off the old man or my religious garment and put on the new

man that is Christ or Science, and I fight these errors and show that they are

all the makings of our own mind. As I stand outside of all religious belief,

how do I stand alongside of my followers? I know that I, this wisdom, can go

and impress a person at a distance. The world may not believe it, but to the

world it is just such a belief as the belief in spirits; but to me it is a fact

and this is what I shall show."14

Nor were Quimby's

allusions to the higher wisdom, as Robert Peel argued problematically,

"recurrent elements of spiritual idealism which contradict the author's

basic position." 15 A clear hierarchy of error and truth, in fact, ran

through all of Quimby's writings. Mind, with its beliefs and opinions, existed

as part of a material order of error; wisdom rose above it; somehow

Quimby-despite the morass in which all other mortals seemingly found

themselves-lived as a "scientific man" in a realm beyond. Quimby,

like Jesus, inhabited the wisdom world, and Eddy had discovered the connection.

This was so much so that in late 1862 her enthusiasm for her new healer-teacher

embarrassed him publicly, when letters that she wrote to the Portland Courier

in the first blush of her healing experience appeared in print. Quimby stood

"upon the plane of wisdom with his truth," she proclaimed in the

second of these, and he healed "as never man healed since Christ."

"P. P. Quimby," she exulted, "rolls away the stone from the

sepulchre of error, and health is the

resurrection."16

Mary Baker Eddy's

relationship with Quimby ended abruptly in January 1866 when the doctor died.

Bereft of both doctor and mentor (her father Mark Baker had also died three

months before), she poured out her feelings in "Lines on the Death of Dr.

P. P. Quimby, who healed with the truth that Christ taught, in

contradistinction to all isms." The poem was published in the Lynn

(Massachusetts) Weekly Reporter almost a month later. Meanwhile, less than two

weeks after Quimby's death, Eddy fell on ice on her way to a meeting,

experienced injuries that caused severe head and neck pain with possible spinal

dislocation, and three days later, in the midst of pain that her homeopathic

physician could not assuage, read a New Testament passage. An account of one of

the healing miracles of Jesus, the narrative, she later claimed, triggered an

intense experiential state of awareness. Eddy, according to her own report and

denominational tradition, had "discovered" Christian Science.17

If so, what she took

away cognitively from the experience, at least as she later constructed it,

linked the wisdom discourse of Quimby to the orthodoxy of her Congregational

Christian past. Now, though, instead of immersion in the world of error that

pervaded most of Quimby's writings, a felt sense of God as the only reality

became the key to her healing and all healing. Even as Eddy brought the

unorthodox Quimby to the orthodoxy of her past, the Calvinism of her religious

construction was noticeable. At least part of the attraction of the Quimby

theology for Eddy was its predication of wisdom as an unchanging and

transcendent reality. Whatever Eddy's connections to spiritualism-and, as we

shall see, they were many-the theological immanence that spiritualism

proclaimed was for her in the end untenable.

Eddy did, to be sure,

teach what might be called a Christian version of final union with an Oversoul

become God. In the first edition of her textbook Science and Health, for

example, she wrote that "we are never Spirit until we are God; there are

no individual 'spirits.''' She went on to exhort that "until we find Life

Soul, and not sense, we are not sinless, harmonious, or undying. We become

Spirit only as we reach being in God; not through death or any change of

matter, but mind, do we reach Spirit, lose sin and death, and gain man's

immortality." But the journey was decidedly one to a transcendental state

and order. The published 1876 edition of Eddy's teaching pamphlet Science of

Man, for example, declared that "Intelligence" was "circumference

and not centre" and that "Soul and

Spirit" were "neither in man nor matter." Similarly, the

standard edition of Science and Health from 1906 affirmed "God as not in

man but as reflected by man" and warned against "false estimates of

soul as dwelling in sense and of mind as dwelling in matter." In her

"new departure of metaphysics," Eddy elsewhere told followers,

God was "regarded more as absolute, supreme;' while "God's

fatherliness as Life, Truth, and Love" made "His sovereignty

glorious." In practical terms, testimonies of healing the sick through

Christian Science treatment would be the means to glorify God and scale

"the pinnacle of praise."18 Thus the Eddy who rejected the

predestinarian views of her childhood church still exalted the supreme majesty

of God in ways that proclaimed the underlying Calvinism of her past.

Christian Science

scholar Stephen Gottschalk notes these connections in his theological study of

Eddy's place in American religious culture, and he notices as well the

essential Calvinism of the metaphysical dualism she propounded. "In

Christian Science as in Calvinism," Gottschalk observes, "one is

clearly confronted with the Pauline antithesis of the Spirit and the

flesh." It is arguable, too, that the warfare model that permeates so much

of Eddy's writing reinscribes Calvinism with its traditional narratives of the

battle between good and evil, between God and the devil, in the life of the

soul. In fact, any sustained contact with the corpus of Eddy's writings reveals

the periodic invocation of "sin" as a habitual way to distinguish

reprehensible states of mind and life. We have already seen her identifying the

loss of "sin" in "Life Soul" in the first edition of

Science and Health. Later, both in the Manual of the Mother Church (1895) and

in the standard (1906) edition of Science and Health, Scientists and seekers

could find among the six "Tenets" of the Mother Church one that

acknowledged "God's forgiveness of sin in the destruction of sin and the

spiritual understanding that casts out evil as unreal." "Rule out of

me all sin;' the Church Manual asked Scientists to pray daily.18

Ostensibly committed

to the unreality of sin and evil, Eddy's writings-with their warfare mentality

that equaled or amplified Quimby's polemical stancehid

a Calvinist devil lurking beneath the metaphysical surface, an evil that

displayed a very tangible presence. Toward the end of Eddy's life, that

presence took the form of a heightened personal fear of "malicious animal

magnetism" ("M.A.M."), as prayer workers stationed outside her

door through the night contended against claimed magnetic onslaughts. But much

earlier, it is hard not to detect a palpable sense of evil that preoccupied

her. Her contentious relationships with students and former students were cast

by Eddy in terms that invited, for her, a felt sense of sin (of others toward

her) and the presence of Satan, even if the name itself was banished to the

outer darkness of theological incorrectness. On paper, sin was "the lying

supposition that life, substance, and intelligence are both material and

spiritual, and yet are separate from God." But Eddy herself allowed that

sin was "concrete" as well as "abstract," and in many life

situations the concreteness was manifest. Sin was a "delusion" and a

"lie," but even if she told her followers not to fear it, she acted

as though she feared it herself.19

More than that, in

the consistent Christian Science language of "mortal mind" that Eddy

created it is hard not to read a transliterated script for sin and, indeed, for

the old Calvinist theology of the total depravity of humankind. Eddy herself

was uneasy about the term, calling it a "solecism in language" that

involved "an improper use of the word mind." However, she was willing

to live with the "old and imperfect" in her "new tongue."

In this context, mortal mind meant "the flesh opposed to Spirit, the human

mind and evil in contradistinction to the divine Mind, or Truth and good."

Still further, her "Scientific Translation of Mortal Mind" announced

its "first degree" to be "depravity," identifying depravity

with the physical realm of "evil beliefs, passions and appetites, fear,

depraved will, self-justification, pride, envy, deceit, hatred, revenge, sin,

sickness, disease, death." Eddy was adamant in her insistence that, seen

from and in the divine Mind, evil itself was unreal and that, therefore, mortal

mind was mind existing in a state of error. Still for all that, the language of

recrimination that she cast upon it, with its emotional tone of repugnance and

rebuke, suggests that she was making something out of this nothing in her act

of warfare against it. As Ann Braude has stated, Eddy "had no doubt that

the mortal, human aspects of each person reflected the total depravity of

Adam's legacy;' and she was "preoccupied with fighting the dangerous

temporal effect of the belief in evil."20

Eddy also feared a

lifestyle that emphasized ease, relaxation, and pleasure, this expressed in

tones that suggest the Calvinist ethos that shaped her. In the spring of 1906,

for example, she wrote to the young John Lathrop, who formerly served as

household staff, telling him of her sorrow "over the ease of Christian

Scientists." She lamented that they were habituated in the

"pleasures" of "sense." "Which drives out quickest the

tenant you wish to get out of your house, the pleasant hours he enjoys in it or

its unpleasantness?" she asked rhetorically. A few years later, toward the

very end of her life, her household staff, who had typically observed a Puritan

rigor, began to relax in ways that distressed her. Staff Scientists were less

vigilant in protecting her against M.A.M., and they read the Boston newspapers,

played golf, went for auto rides, and stopped sometimes at libraries in the

neighborhood. On one late-summer occasion, recounts Stephen Gottschalk, Eddy

looked out of her window as two staff members threw a ball back and forth and

another attempted to walk on his hands. She endured, as Gottschalk quotes from

Calvin Frye's diary, "a very disturbed night and a fear she could not live

!"21

The perils of flesh

and spirit, however, deferred to the presence of spirits when Mary Glover's

first edition of Science and Health appeared in print in 1875. Published nine

years after Quimby's death, the work displayed a woman who now spoke with an

authority of her own and a sense of knowledge gained through hard-won

experience. The text likewise displayed a woman at pains to separate herself

from mesmeric and mediumistic phenomena, so that the new warfare of the spirit

that Eddy waged was clearly directed against spiritualism and its magnetic

culture. Like her former mentor Phineas Quimby and like the founders of

Theosophy, she saw in mesmerism "unmitigated humbug," and her

estimate of spiritualism was equally denunciatory. In the three-page preface to

her ambitious first edition, Eddy (then Glover) singled out mesmerism for

direct rebuke. "Some shockingly false claims" had already been made

regarding the work in which she was engaged. "Mesmerism" was one, she

stated flatly, and her denial was total. "Hitherto we have never in a

single instance of our discovery or practice found the slightest resemblance

between mesmerism and the science of Life."22

If Eddy seemed

defensive, she had reason to be. In her Quimby years, she had surely traveled

in mesmeric and spiritualist circles, and even as she took her first steps in

Lynn as a practitioner of what became Christian Science many who were close to

her thought of her as a medium. Her early advertisement of her new system of

healing through "Moral Science" in the spiritualist Banner of Light

in 1868 no doubt helped to fuel the assumption, and so, no doubt, did her

outsider stance toward conventional medical methods.23 That acknowledged, the

vehemence of her condemnation of mesmerism and spiritualism was still

startling. Eddy, by virtue of her emotional engagement, ended up affirming what

she denied. Matter became real and so did mesmeric influence and spirit contact

with it when she fought them so strenuously. From another point of view, Beryl

Satter has suggested that Eddy's "healing process bore a family

resemblance to mesmeric or hypnotic healing," 24 and although the divine

Mind that healed and mortal minds caught in the morass of error were profoundly

different in her system (and so not exactly comparable), still the ghost of

resemblance was there.

"Mesmerism,"

she told students, was "a belief constituting mortal mind," and

"error" was "all there is to it, which is the very antipode of

science, the immortal mind." "Mesmerism" was "a direct appeal

to personal sense ... predicated on the supposition that Life is in matter, and

a nervo-vital fluid at that." It was "error

and belief in conflict" and "one error at war with another"; it

was "personal sense giving the lie to its own statements, denying the

pains but admitting the pleasures of sense." Why was it so dangerous? The

answer lay in its proximity to Spirit, its ability to function as a lying proxy

for the truth. "Electricity," she wrote, "is the last boundary

between personal sense and Soul, and although it stands at the threshold of

Spirit it cannot enter into it, but the nearer matter approaches mind the more

potent it becomes, to produce supposed good or evil; the lightning is fierce,

and the electric telegram swift." Eddy's argument, in fact, replicated the

theoretical model of homeopathy in which infinitesimal doses were more potent

than gross ones. Homeopaths believed that the same substance that caused the

symptoms of a given disease in a well person would cure the disease in a

patient who was suffering from it. The key, however, was the "potentization"

of remedies by increasingly radical dilutions to the point that, physically

speaking, not even a trace of the original substance remained. Now, in Eddy's

warning model, not only homeopathy but also the assorted healing modalities

that kept it company achieved heightened power with the increased dilution of

their physicality. "The more ethereal matter becomes according to accepted

theories, the more powerful it is; e.g., the homoeopathic drugs, steam, and

electricity, until possessing less and less materiality, it passes into

essence, and is admitted mortal mind; not Intelligence, but belief, not Truth,

but error."25

Siding with the

mentalists and not the fluidic theorists regarding mesmeric and related

electrical phenomena, she declared electricity to be "not a vital fluid;

but an element of mind, the higher link between the grosser strata of mind,

named matter, and the more rarified called mind." Rarefied or gross, the

danger in the magnetic world and its environs was ubiquitous. Thus phrenology

fared no better in Eddy's estimate, making an individual "a thief or

Christian, according to the development of bumps on the cranium." "To

measure our capacities by the size or weight of our brains, and limit our

strength to the use of a muscle;' she admonished, "holds Life at the mercy

of organization, and makes matter the status of man." Taking aim at the

health reform movement of the era, which bowed "to flesh-brush, flannel,

bath, diet, exercise, air, etc.;' she declared "physiology" to be

"anti-Christian." Meanwhile, not only magnetism but also

"mediumship" and "galvanism" were "the right hands of

humbug;' and mediumship by itself was an "imposition" and a

"catch-penny fraud."26

In Eddy's reading,

mesmerism and mediumship were clearly intertwined, lumped together as, for

practical purposes, they had functioned in the spiritualist community in which

she had sometimes, if warily, participated. Moreover, she had been called a

spirit medium, not a mesmerist, and so she experienced mediumship as an

especially potent enemy against which she needed to contend. "We have

investigated the phenomenon called mediumship both to convince yourself of its

nature and cause, and to be able to explain it;' she told the student readers

of Science and Health, although she expressed some reservations about her

ability to do the second. Her critique, though, was undeterred, and it was

trenchant. The Rochester rapping’s "inaugurated a mockery destructive to

order and good morals." Likewise, the "mischievous link between mind

and matter, called planchette, uttering its many falsehoods," was "a

prototype of the poor work some people make of the passage from their old

natures up to a better man." Eddy did not deny the sincerity of many

involved in the seances, enjoining readers to "make due distinction

between mediums hip and the individual" and affirming that there were

"undoubtedly noble purposes in the hearts of noble women and men who believe

themselves mediums." But like the (later co-founders of the Theosophical

Society in New York), Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott at the (ironically

named) Eddy farm, she pointed to the loss of mastery that accompanied

mediumistic work. Mediumship, she warned, was a "belief of individualized

'spirits,' also that they do much for you, the result of which is you are

capable of doing less for yourself."27

Eddy bristled angrily

at mediumistic claims. Mediumship presupposed that "one man" was

"Spirit," and that he controlled "another man" that was

"matter." It taught that "bodies which return to dust or new

bodies called 'spirits'" were "experiencing the old sensations, and

desires material, and mesmerizing earthly mortals." It taught, too, that

"shadow" was "tangible to touch" and that it produced

"electricity" and similar phenomena. She found these conclusions to

be "ridiculous." The spirit manifestations were the "result of

tricks or belief, proceeding from the so-called mind of man, and not the mind

of God." Mediumship itself overlooked "the impossibility for a

sensual mind to become spirit, or to possess a spiritual body after what we

term death," something that science revealed as "more inconsistent

than for stygian darkness to emit a sun-beam." "To admit the

so-called dead and living commune together," Eddy asserted categorically,

was "to decide the unfitness of both for their separate positions."

"Mediumship assigns to their dead a condition worse than blighted buds or

mortal mildew, even a poor purgatory where one's chances for something narrow

into nothing, or they must return to the old stand-points of matter." Its

foundations lay in "secretiveness, jugglery, credulity, superstition and

belief." Because of its mystical ambience, it could "do more harm

than drugs."28

As warrior of the

spirit, Eddy with her pungency equaled or exceeded the contentiousness of

Quimby, making a similar case but making it now out of a heterodox Calvinism

instead of her mentor's heterodox liberal Christianity. And like the

unsystematic short pieces left by Quimby, her more systematic work pointed

beyond the language of argument to a lived engagement with powerful ideas. The

center of Eddy's work was practice, and the center of her healing practice was

argument. In the language game that was her metaphysical system, the

practitioner argued against the error that was matter, against the mortal mind

of the patient-client in its mesmerized "Adam-dream" - until the

healer broke through to Truth and Principle. The absolutism of Eddy's stance

was uncompromising. The false belief in matter condemned people to the

scenarios of illness and pain that they experienced. The healing role of the

Christian Science practitioner was meant not so much to provide compassionate

care as to demonstrate Truth in an ideal order that reduced the physical to the

nothing that it was, an order that, in short, proved the claims of the

Christian gospel as Eddy herself understood them. Like the utterly sovereign,

utterly transcendent God of Calvinism, like the God out of the whirlwind in the

book of Job, Truth brooked no compromise and demonstrated its reality by

vanquishing the appearance of disease and disorder. Christian Science healing

existed not to enhance matter and materially based humanity. It existed only to

advance the Truth, the Principle, of God.

There was, of course,

a cutting irony in Eddy's adamant antimaterialism-an antimaterialism that Stephen Gottschalk in recent work has

noticed so clearly when juxtaposed to the early wealth of the Christian Science

Mother Church and the rising status of its mostly female practitioners.29 But a

facile coupling of the material success of the movement to the basic Eddy

theology does not stand up to scrutiny when the founder's essentially Calvinist

heterodoxy is understood. Still more, the easy identification of Christian

Science as a species of what Sydney Ahlstrom called "harmonial

religion" is problematic. Although the term has obscured more than it

reveals even for New Thought, in the case of Christian Science it misreads the

evidence on almost all counts. For Ahlstrom, "harmonial"

religion signified "those forms of piety and belief in which spiritual

composure, physical health, and even economic well-being" were

"understood to flow from a person's rapport with the cosmos." But

with human lives mired in sickness, sin, and death-the triadic legacy of mortal

mind-Eddy's system taught no harmony at all for the material realm but instead

total and uncompromising war. Moreover, when a "saved" Christian

Scientist lived out of Truth and Principle, seeing evil for the nothing that it

was, there was quite literally nothing with which to harmonize. One lived in

Truth, or one did not. One could simply not harmonize nonexistence with

Principle. Eddy's antimaterialist "scientific

statement of being;' in the familiar 1906 edition, brought home the point:

"There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is

infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation, for God is All-in-all. Spirit is

immortal Truth; matter is mortal error. Spirit is the real and eternal; matter

is the unreal and temporal. Spirit is God, and man is His image and likeness.

Therefore, man is not material; he is spiritual."30

Christian Scientists

did, of course, at times speak colloquially, as other Christians did, about

getting into harmony with God. Eddy herself had taught that sickness, sin, and

death were "inharmonies" and had pronounced

all past, present, and future existence to be "God, and the idea of God,

harmonious and eternal." "Harmonious action," she wrote,

"proceeds from Principle; that is, from Soul; in harmony has no Principle."

She had suggested in Science and Health, too, that the discovery of "Life

Soul" would make one harmonious. Moreover, at the very core of a formulaic

healing event lay an intense realization on the part of a Science practitioner

of the unreality of the patient's particular plight or illness and the divine

perfection that instead was and had been ever present. Such realizations could

be couched in the language of harmony. But perusal of Christian Science

literature reveals no preference for the term or the discourse of harmony, and,

still more, Christian Science healers were accustomed to describing their

healing work not only as "treatment" but also, and quite typically,

as "argument." When they healed, they spoke of "demonstrating

over" illness in a metaphor that evokes science and contest at once. As

Stephen Gottschalk notes, "the aims and theological standpoint of

Christian Science and of harmonialism differ so

markedly that the two cannot be assumed to represent the same tendency."

Pointing as well to the pain and suffering that characterized Eddy's personal

life, he found the harmonial ascription especially

inappropriate. Eddy needed to be saved, to be born again; and she felt in her

"discovery" of Christian Science that her new birth in the spirit had

happened.31

Yet if Eddy was a

decided antimaterialist, and if she fought fiercely

against the lingering shadows of mesmerism and spiritualism, the connections

between her new "Truth" and these former partners would not go away.

In the case of mesmerism, we know that early Christian Science practice

included some rubbing or touching of the afflicted area of a patient's body in

the style of mesmerists (and, imitating them, spiritualist healers). This

essentially followed Quimby's practice growing out of his earlier healing

technique in animal magnetism, and he had typically employed water as a medium

for the work. Eddy herself acknowledged that when she started teaching she had

"permitted students to manipulate the head, ignorant that it could do

harm, or hinder the power of mind." According to report, she at first

actively instructed students to rub and touch-not for the patent efficacy of

these gestures but, as Quimby did, because of the belief that they fostered in

the patient: ''As we believe and others believe we get nearer to them by

contact and now you would rub out a belief, and this belief is located in the

brain." Like a doctor's poultice applied for pain, so the healer should

place her "hands where the belief is to rub it out forever."32 Added

to this, we have already seen Eddy's demonstrated fear, stronger as she aged,

of malicious animal magnetism.

In the case of

spiritualism, Ann Braude has pointedly noticed the overlap between Eddy's

theologically driven healing method and the discursive world of the

spiritualist community. Aside from the shared social context in which both

flourished and the similarity of the needs that drew converts to both

spiritualism and Science, the denial of evil in Christian Science from one

perspective made the movement look like spiritualism because of its overt

rejection of this major Calvinist category. Likewise, both spiritualism and

Christian Science exalted science to deific proportions; both opposed

orthodoxies in medicine as well as religion; and both encouraged egalitarianism

by promoting women as leaders and by supporting lay ability to function as

healers. In other words, in both systems the patient could easily take charge,

and each system thus operated on a more or less level playing field. Moreover,

as Braude argues, the "most significant" agreement came with the

belief that there was "no change at death." True the lack of change

existed, for spiritualists, as a function of the continuing material existence

of spirit bodies after the change called death and, for Scientists, in the fact

that there were never any real material bodies anyway. Even so, an underlying

model of permanence and denial of death's edge characterized both movements.33

The language of the

"Father-Mother God," the "Christ Principle," and God as

Principle was, as we have already seen, part of the rhetorical world of

spiritualism. Beyond that, Eddy's early Christian Science followers seemed to

move easily in and out of the spiritualist community. Were the new

practitioners mostly women (in the ranks as well as leaders, as we will see) -

former spirit mediums? Did they transpose their performances from spirits to

Spirit in the same manner that the women whom Ann Braude has studied left

trance mediumship on public stages for feminist speeches in their own names?

Except for a few cases, no clear answers can be given. But the questions hang

there for the asking. Braude has, for example, identified the combinative

thrust of the Boston periodical The Soul in the 1880s, a periodical at home in

both spiritualist and Christian Science circles. At least one medium and her

husband-the later well-known Swartses-attended a

Christian Science course taught by Eddy, even as the husband tried to teach

what he learned from Eddy in spiritualist contexts. Beyond this, there was the

over-protest of Eddy's relentless attack on spiritualism- "mesmerism,

manipulation, or mediumship" as "the right hand of humbug, either a

delusion or a fraud." As Braude observes, Eddy's preoccupation with

separating Science from spiritualism suggests "that she viewed

Spiritualism as the religion with which her own faith could be most easily

confused."34

Still, like Blavatsky

and Olcott-from whom she strenuously separated herself as well- Eddy recognized

clairvoyance as fact and thought that spiritual manifestations involved mind

reading on the medium's part. However, unlike Theosophists, who looked to elementals

for the production of phenomena, she thought that materializations were the

products of the mediumistic mind. Yet she did not think that, in theory, spirit

communication was impossible. Rather, the reality of spirit communication

needed to be demonstrated outside of matter since, by definition, matter was

irrevocably yoked to appearance and unreality. Spirits, in the plural,

were "supposed mixtures of Intelligence and matter" that,

"science" revealed, could not "affinitive or dwell

together." But Spirit itself, in the singular, was a thoroughly different

case: there was "no Intelligence, no Life, no Substance, no Truth, no Love

but the Spiritual." Eddy recognized, too, the existence of trance states and

the power they gave to otherwise reticent speakers.35 Finally, like the

spiritualists, in her own way she supported and promoted feminism even if she

had difficulties yielding authority to talented individual women who came to

her.

Given all of this,

the Christian Science that Eddy shaped in her mature years reconstituted

spiritualism, turning it inside out to craft a monistic system based on

nonmaterial spirit and inverting its liberalism in her lingering Calvinism. Her

reconstitution achieved manifest success, shaping its metaphysics to a new and

Christian organization that demonstrates the extent to which metaphysical combinativeness could reach. The formerly self-effacing

Eddy spoke and acted with decisive authority as a new religious leader, and she

made and unmade institutions in the service of her cause. The roster of her

doings and undoings quickly tells the story. She

established the Christian Scientists' Association in 1876 and restructured it

into the Church of Christ, Scientist in 1879. By 1882, she founded the

state-chartered Massachusetts Medical College in Boston and, by 1886, the National

Christian Science Association. In these years of rapid growth and development,

she encouraged graduates of the college to create regional institutes that

would spread Christian Science throughout the nation. In the states of Iowa and

Illinois alone, according to Rennie Schoepflin, sixteen institutes arose on the

Eddy model in the 1880s and the 189os. But in 1889, with divisiveness in church

governance and increasing independence among former students, she dissolved the

Christian Science Association, closed her college, and disbanded the Church of

Christ, Scientist, all in moves to centralize and to regain control. Several

months later, in 1890, she requested that the National Christian Scientist

Association adjourn for a three-year period. Then, in 1892, she reorganized the

Boston church, founding the "Mother Church" so that Scientists from

all across the country would need to apply for membership therein to remain

within the institution.36

Organization

proceeded apace with Eddy's publication, in 1895, of the Manual of the Mother

Church, legislating governance matters in detail, and with the creation, in

1898, of the main administrative units that would promote her teaching. So

tightly did she organize governance that Stephen Gottschalk could remark,

"Perhaps the most amazing thing about Mrs. Eddy's death was the fact that

it had so little apparent effect on the movement."37 At the same time,

Eddy had committed her faith to the printed word as a major means to

disseminate her new reading of the Christian gospels. From early on,

practitioners and patients alike were urged to read Science and Health. Less

than a decade later (in 1884), the first number of the Journal of Christian

Science appeared (called the Christian Science Journal from 1885), with Eddy

herself as editor until she turned the journal over to other promising women,

like Emma Curtis Hopkins, who was soon fired and went on to become a prominent

New Thought leader. In addition, Eddy created, in 1898, the Christian Science

Weekly, subsequently renamed the Christian Science Sentinel, and the same year,

too, established the Christian Science Publishing Society. When the well-known

Christian Science Monitor was founded in 1908 to provide a Christian Science

perspective on national and international news, it came under the aegis of the

publishing society, as did numerous other promotional materials for the church

and for Christian Science theology.

Eddy left Boston,

where she had lived at the center of her movement for seven years, and in 1882

took up residence more reclusively near Concord, New Hampshire. Later, in 1908,

she moved to Chestnut Hill, not far from Boston, where she ended her days. During

her senior years, she oversaw a thriving movement that attracted increasing

numbers of followers and received considerable notice in the press and public

mind, some favorable and some decidedly less so. In Lynn, where Eddy had

gathered her earliest class of students, they came mostly from the working

class. But as the movement took off, this profile began to change. Stephen

Gottschalk, who has pointed to occupation as an indicator of class status,

notes-summarizing a Harvard doctoral dissertation-that by the year of Eddy's

death Christian Scientists largely came from the middle class, a situation that

Gottschalk sees as mostly "consistent" from 1900 to 1950.38 Most had

come, too, as believing Protestant Christians, although they had their quarrels

with orthodoxy. Meanwhile, as the prominence of female leadership already

suggests, many more women than men joined the movement. By the last decade of

the nineteenth century, five times as many woman practitioners could be counted

as men. By the next decade, in 1906, Christian Science membership was 72-4

percent female, at a time when all denominations together averaged 56,9 percent

women in their ranks. The pattern apparently continued through the twentieth

century, since in the 1970s the ratio of women to men within the denomination

was eight to one.39 Arguably, a new form of mediumship had arisen in their

midst, as women mediated no longer the spirits from the second or further

spheres but instead what Scientists claimed was Spirit itself-Principle, Truth,

God, and (when gender references were made) Eddy's Father-Mother God. Without

their "realization" as practitioners of each patient's

"true" state, the Truth-and healing-would not be manifested in

particular human lives. So the women put up shingles, placed advertisements,

and collected set fees-professionalizing their healing work as the seance

mediums had earlier professionalized their services.40

Nor did the women

shun the mission field. They roamed widely as itinerant teachers, bridging the

gap between domestic and public spaces and garnering a swiftly building

membership for Christian Science. Rennie Schoepflin has cited statistics, for

example, showing a net gain of an astounding 2,50 percent in Christian Science

membership between 1890 and 1906, when 40,011 Scientists were claimed. Although

Eddy banned the publication of membership figures after 1908, the number of

practitioners continued to grow in the early twentieth century, with 5,394

globally in 1913 and 10,775 in 1934.41 Like the earlier mediums who spoke in

public when the spirits prompted, Christian Science women apparently felt

compelled by their sense of Truth to spread a public gospel. The complex

motivations of their missionary impulse point, once again, to the combinative

milieu in which American metaphysical religion arose and flourished. In that

milieu, too, despite all of Eddy's efforts to build an ecclesial edifice

unmoved by religious change and reconstruction, the religious work that was

Christian Science repeatedly exhibited the combinations and recombination’s

that were continually remaking metaphysics.

To some extent,

Eddy's very claims to uniqueness (even if partially correct), and to permanence

and impermeability, brought change to her door. As the standard narrative of

the discovery of Christian Science took shape in her remembered past and its

public reconstruction, the gradualism of her early healing practice gave way

before Eddy's testimony to a startling single moment of Truth. The mentorship

of Quimby dissolved before the direct visitation of Spirit. Others, however,

did not forget. Quimby's former patient-students Warren Felt Evans, Julius

Dresser, and Annetia Seabury Dresser either

indirectly (Evans) or directly (the Dressers) challenged Eddy's erasure of the

Quimby legacy, even as the legacy continued to function in a rising

"mind-cure" movement. At the same time, disenchanted Christian

Scientists left Eddy when their views conflicted with her vision or their

persons with her personality. They believed that they found in the growing

mental healing movement a kinder, gentler, and more expansive version of what

they had learned in Eddy's world. Healers shared their skills and news with

clients who, in turn, became other healers, other sharers. The term

"Christian Science" was invoked freely, used in a generic sense as a

description of the new vision and healing practice. Numerous periodicals showed

what was happening (Gary Ward Materra discovered some

117 in existence by 1905), and so did popular books and monographs (Materra found 744 booklength

works for the same period). A networking movement had begun and was spreading

fast.42

It was not until the

1890S that a clear New Thought identity would be posited, and that would occur

in the context of Eddy's copyright on the term "Christian Science" in

the early part of the decade and at least partially because of it,98 But the

rift between Eddy's Christian Science and this developing "mental

science" or generic Christian Science movement existed already in the

tensile structure of Quimby's thought, held together, as it was, by his ability

to contain paradox and anomaly in a persuasive metaphorical quasi system.

Certainly his "wisdom" transcending the error-ridden minds of his

patients and their sickness affirmed the ideal order that Eddy later promoted

as Spirit, Substance, Intelligence, Truth, and the like. But, as we have also

seen, Quimby saw wisdom not only as transcendent but also as a solid or even

fluidic substance pervading all reality, much in the manner of the old magnetic

fluid. He was facile enough mostly to avoid the terms fluid and ether, but

nonetheless their presence remained in the characteristics that he attributed

to wisdom.43 Even as Eddy became an absolutist of the ideal, Quimby straddled

both worlds-affirming a wisdom beyond sense and matter and yet introducing

sensate concepts as palpable, lived metaphors for the experience of wisdom.

Nowhere can this be seen more than in Quimby's homegrown speculations on smell

and its relationship to a wisdom transcending the senses yet within them.

Quimby smelled wisdom, and he smelled sickness. He thought of the odors that he

absorbed as so many particles of the divine in a kind of etheric atmosphere

surrounding a subject,lOo And he linked their

diffusion as mediumistic bearers of knowledge, or wisdom, to words and

language, which also functioned as mediumistic bearers of the same.

In so doing, Quimby

hinted once more of his debt to spiritualism and, especially, to Andrew Jackson

Davis. In his speculations on magnetism, Davis had taught that each human soul

was encircled by an "atmosphere" that was "an emanation from the

individual, just as flowers exhale their fragrance." Moreover, he had

posited, because of the emanation, "a favorable or unfavorable

influence" that one person could have over another (this last a source,

perhaps, of Eddy's later notion of M.A.M.). In his turn, Quimby pushed the

metaphor and materialized it further. He likened the "brain or

intellect" to a rose, and he thought that intelligence came through its

smells as they emanated. Again, each belief, for Quimby, contained "matter

or ideas which throw off an odor like a rose." In fact, humans typically

threw off "two odors: one matter and the other wisdom." Matter,

identified with the human mind (not wisdom), produced an odor that was like a

"polished mirror," with fear reflected in it as "the image of

the belief." Wisdom was wise because it could "see the image in the

mirror, held there by its fear." Quimby was the case in point, for it was

his "wisdom" that disturbed his patient's reflected

"opinion," deadening the mirror "till the image or disease"

had disappeared. Mostly, in the terms of the analogy, Quimby focused on the

smell of matter and its manifestation as illness in the life of a patient.

"The mind is under the direction of a power independent of itself,"

he explained, "and when the mind or thought is formed into an idea, the

idea throws off an odor that contains the cause and effect." The odor was

"the trouble called disease," and-unlike the doctors who knew nothing

about it-Quimby himself smelled the "spiritual life of the idea" that

was error. From there he could launch his healing work to banish it.44

This was because

Quimby could also smell wisdom - a different odor - which his ailing patients

were unable to detect, even though the smell of wisdom could, at least

theoretically, come to them. "As a rose imparts to every living creature

its odor, so man become impregnated with wisdom, assumes an identity and sets

up for himself;' he argued. This wisdom might be called the "first

cause" and might be construed, too, to exude an "essence" that

pervaded "all space." Yet, in a distinction that was crucial for Quimby,

the sense of smell and the other senses belonged not to the "natural

man" but to his "scientific" counterpart. Such a

"scientific man" - Quimby himself-knew odor to be the most potent of

the senses, conveying knowledge of good (as in savory food) and of danger, for

smell was an "atmosphere" that surrounded an object or subject.

Thus-and this was where he was headed-the common atmosphere of humans in

similar states of fear (in the presence of danger) led to "a sort oflanguage, so that language was invented for the safety of

the race." Quimby, in short, had arrived at the idea that "the sense

of smell was the foundation of language" and at the overarching conviction

that from the material process came the higher wisdom. "Forming thought

into things or ideas became a sense;' and the process was

"spiritual."45

Moreover, if the

sense of smell was, indeed, the "foundation of language;' it was also

itself a language. Humans, like roses, threw off odors; odors enabled Quimby to

diagnose erroneous states of mind being manifested as diseases; odors also

conveyed character. Still further, distance was no factor in intuiting smells

and odors. Situated in wisdom, he claimed, "my senses could be affected

... when my body was at a distance of many miles from the patient. This led me

to a new discovery, and I found my senses were not in my body but that my body

was in my senses, and my knowledge located my senses just according to my

wisdom."46 Quimby's thinking on these matters was often circular, muddled,

and less than clear. But through his sometimes strained efforts to explain he

was laying the groundwork for later New Thought theologies of immanence and

panentheism. Profoundly different from the hauntingly Calvinist transcendent

God of Eddy, with an ultimate divine alterity, the New Thought deity would

beckon as the God within and the God who, like a superconscious etheric fluid,

permeated all things.

It was Warren Felt

Evans (1817-1889), Quimby's other major theological student alongside Eddy, who

would articulate - much further and more clearly than Quimby-the possibilities

and powers of the resident God. At the same time, like his doctor-teacher, Evans

protected the twofold nature of divinity, Mind transcendent and Mind within.

Son of a Vermont farming family, Evans attended Chester Academy, spent a year

at Middlebury College, and then transferred, in 1838, to Dartmouth in New

Hampshire. He never graduated, since midway through his junior year he felt a

calling to the Methodist ministry. According to Charles Braden, he held, at

various times, eleven different positions for the denomination. Then, in 1864,

he joined the Swedenborgian Church of the New Jerusalem, and the profound and

abiding influence of Swedenborg became apparent in his subsequent writings. The

break from his Methodist past and his move in an unorthodox spiritual direction

were probably at some level stressful, for he experienced both serious and

chronic "nervous" disease. Close to the time he officially became a

Swedenborgian, his physical condition brought him to Quimby's Portland door.

Like Eddy, Evans was healed, became a Quimby student, and also felt a calling

to be a healer himself. He began a mental healing practice in Claremont, New

Hampshire, but by 1867 had moved to the Boston area, where, with his wife M.

Charlotte Tinker, he spent over twenty years practicing and teaching. Unlike

Eddy and other mental healing professionals, he charged no fees and accepted

only free will offerings. He also apparently read copiously and wrote a series

of widely influential books on mental healing in a religious context.47 If we

track the changes from the earliest to the latest of these works, we gain a

sense of the shifting discourse community of American metaphysics as it

transitioned from high-century phrenomagnetic and Swedenborgian seance

spiritualism to the theosophizing world of the late

1870s and 1880s.

The earliest of

Evans's six mental healing books (he had previously written four short works on

aspects of Swedenborgian theology) appeared in 1869 and the latest in 1886,

together revealing a disciplined, ordering mind and a facility in argument and

exposition. Evans was bibliographically responsible in ways that signal a

professionalism and attention to detail not found in earlier, and especially

vernacular, authors. Often, but not always, he parenthetically cited sources of

quotations, giving an author's surname, a short title, and the page or pages.

Aside from the general sophistication of these works and their at-homeness in

both religious and scientific worlds of contemporary discourse, they were cast

in a decidedly different tone from the work of either Quimby or Eddy. Instead

of polemicism and battle, in Evans readers could find

affirmation and a kind of irenic catholicity that consciously combined sources

in an almost theosophical style.

The first of the

mental healing books, The Mental-Cure, disclosed an Evans who was a thorough

Swedenborgian and also comfortable in a spiritualist milieu that resonated with

the harmonial theology of Davis. Mind was an

"immaterial substance," but matter was also a substance, one

associated with the sense experience of resistance and force. All humans were

"incarnations of the Divinity," love was supreme, and the good lay

within, with "great futurities ... hidden in the mysterious depths of our

inner being."48 A combined Swedenborgian-spiritualist millennialism

pervaded the text with its noticeable allusions to a coming (uppercase)

"New Age" (of the Holy Spirit), which was "now in the order of

Providence dawning upon the world." Meanwhile, its easy assumptions

regarding the real existence of spirits, its familiar references to the "Seeress of Prevorst"

its citation of the ubiquitous spiritualist Samuel B. Brittan, and its doctrine

of spiritual spheres pointed in the same Swedenborgian-spiritualist direction.

So did its understanding of death as a "transition to a higher life"

and "normal process in development." References to Gall and to

phrenology as well as magnetic allusions indicated Evans's familiarity with

spiritualist discourse, and there was the by now well-recognized caveat

regarding magnetic power and peril ("a power that can be turned to good account,

or perverted to evil"). Still more, in the Swedenborgian reading that

Evans gave to "modern spiritualism," we can see the easy conflation

that he and so many others were making between the sources out of which they

built their world. Expounding on the "Swedish philosopher" and his

doctrine of spiritual influx, Evans saw inspiration and "the commerce of

our spirits with the heavens above" as "the normal state of the human

mind." In that context, what was "called modern spiritualism"

was "only an instinctive reaction of the general mind against the

unnatural condition it has been in for centuries."49