So why is Turkey so quiet in spite of

Gul's ascent?

On August 24, 2007, Newservices announced that; The Turkish military will

safeguard a secular and democratic Turkey against the "evil" Islamic forces

in the upcoming presidential election, military chief Gen. Yasar Buyukanit said on the military's Web site Aug. 27. The

military has seized power from civilian governments three times in the past and

has threatened to do so again if presidential candidate Foreign Minister

Abdullah Gul wins the election.

Throughout this five

part article/study we tried to understand the reasons that made political Islam

in Turkey such a formidable force against the established order. This rise of

political Islam was inexorably connected to the great transformations that occurred

in the nature of global social relations of production. The agents of this new

hegemonic drive of global capitalism and its ideology of transnational

liberalism, the multinational corporations, Western financial circles, members

of the World Economic Forum, etc, had established

politically and economically convenient alliances with the Islamist movement

whenever they saw fit. But the real unification of these sides happened after

the profitability crises struck international capitalism and the Fordist style

of accumulation just after 1973.

Historically, the

significance of my explanation is, due to the fact that at around the same time

frame, Turkish capitalism entered its own crisis of accumulation largely

stemming from the foreign currency shortage that was created by the Turkish

import substitution policies. With the coincidence of geopolitical and economic

interests of both the USA as the superpower of capitalism, and the Saudi family

in their aspiration for hegemony in the Arab world, against the Iranian

revolution and the Soviet threat, the late 1970s and 1980s witnessed a surge in

Islamic financial markets in the international arena whose resources were

mainly diverted to supply the rebels of Afghanistan or the madrasas (religious

schools) of Middle eastern countries, including Turkey.

Within that context,

the Turkish business who wanted to transform the import substitution model into

an export-oriented model launched its structural adjustment project at the

beginning of 1980, which was not implemented due to growing militancy of the working

class. But the Turkish army for the third time in the last three decades,

intervened to stop so-called anarchy and terror in the country in September

1980.

However, the army’s

political repression, new labor, education, privatization, and liberalization

reforms precisely served the interests of the big busines,

and its 1980 structural adjustment program. With the new ideological consensus

around neo-liberalism in economics and the Turkish-Islam synthesis in politics,

and the heavy political repression against the left, coupled with one of the

most restrictive labor and union laws, Turkish governments actively promoted

the Islamic movement.

Islamists not only

used this new ideological means of a Turkish-Islam synthesis but they also

organized around trade unions where the left was crippled, opened new

educational facilities, especially more Imam Hatip High schools and religious

courses, established Islamic financial houses and replaced the state in

providing basic welfare services, penetrating almost every walk of Turkish

social life in an unprecedented way.

The strange

intertwining of the interest of neoliberals and Islamists in Turkey after 1980

can best be explained by the political and sociological effects that

globalization of capitalism has had over the societies. On the economic front

the IMF’s structural adjustment policies which require financial

liberalization, transparency in balance sheets and trade, less government

bureaucracy in transactions, all perfectly fit into the Islamic economics’

agenda. The main Islamic finance agencies saw that nonconventional interest

free banking and trading necessitated costlier supervision and closer

cooperation for the lenders and borrowers in Islamic trade. The transparency

demand of international institutions was a godsend for them in that context.

Secondly, the

deregulatory environment that forced nation states to lessen their financial

controls, as a result of widespread currency markets’ surpassing of time/space

conceptions of nationalism, provided opportunities to Islamic movements to

shift their resources conveniently without strict scrutiny. Thirdly, on the

political and ideological front the fixity of Fordism’s and import

substitution’s modern day production and social relations that promote nuclear

family, mass consumption, mass unionization and partial participation of the

popular classes into the governance structures of national economies, suffered

massive setbacks with the neoliberal political and economic assault. That

assault which crippled unions, and previous gains of working classes brought

forth pre-industrial production relationships, mainly patriarchal and kinship

based ones. These relations were the by products of

new globalized production lines that returned to piece by piece wages, small

businesses, nonunionized independent and skilled workforces. The hierarchies of

those new relationships deepened the ideological vacuum of the post-fordist era, as the abstract individualism of free markets

left people completely helpless in the face of relentless changes within

time/space conceptualizations of nation states and previous industrial era. The

kinship, ethnicity, religious and tribal affiliations gradually resonated more

in the “commonsense” of people as the transnational bourgeoisies effort to

create a world in its own image shook all solid understandings and ossified

relationships. That resurgence of pre-industrial era allegiances was

complemented by the ideologically pragmatic but reactionary alliances of

neoliberals with religious fanatics in the Middle East, and ethnic nationalist

in Eastern Europe. Turkey was even influenced by the culturally sustained

assault of postmodernism on enlightenment ideals which strengthened the doubts

of Turks regarding whether or not there was a secular sustainable human

alternative to all that was happening.

In the Turkish case

the reactionary Turkish-Islamic synthesis was accommodated to big bourgeoisies’

ideological framework in the aftermath of 1980 coup that shifted country’s

direction from import substitution to the export oriented model. The process not

only created a neoliberal Islamist nuevo rich elite that can get along well

with capitalism, but also that pragmatic alliance, in the absence of sound wide

based support to the neoliberal project, engendered new dangerous cracks within

Turkish political scene.

After the 1991 Gulf

War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, through their experiences of the last

decade in education, public administration and export oriented industries, the

Islamic bourgeoisie increasingly contested the dominance of the metropolitan

based big businesses. Meanwhile lower class people flocked to Islam to oppose

strict secularism and the unjust system. In Islam’s oppositional rhetoric,

Kemalist’s top-down style imposition of secularism on population, which equated

western style dressing and behaviors with upwards mobility and respect, were

perceived by Welfare Party activists and supporters as the real basis of class

divisions in Turkish society. One other factor enmeshed Islam into the

political culture that broadly is the Turkish nationalism. Since the foundation

of the republic, the government promoted Muslim identity as a cement that unify

Kurds and Turks against Armenians, Greeks and other minorities. That kind of

manipulation of religion by the state inevitably reawakened old ties to Islamic

identity when the conditions were ripe for the resonation of residual

ideologies. The 1980s and 1990s were those years. Just as the Ottoman elite

emphasized the rule of the just sultan and Islamic just order, a weak

bourgeoisies’ failure to create a completely secular civicnationalist

identity for the population facilitated the Welfare Party’s propaganda efforts

when it referred to Islam as a supra-political feature of Turkish social

formation.

But the generals and

their bourgeois supporters in the 12 September coup as well as in their attempt

to transform society along neoliberal lines through a conservative hegemony

were short sighted. They tried to produce a conservative hegemony by promoting

emergence of Islam. Their neoliberal conservative project did not have any

encompassing solution to the problems of broad layers of the population, who in

the absence of the left alternative channeled their support to Islamists. The

last decade’s disputes between the Welfare Party and its successors and the

civilian military bureaucracy of the state, from the tensions in the defense

budget to the 28 February 1997s “post-modern” coup, lucidly taught us that in

the near future those cracks in the neoliberal project would continue as the

latest successor of Welfare Party, the AKP, has constantly confronted the

military and nationalist elite on the subject of Turkey’s accession to EU and

how to negotiate Copenhagen criteria.

In order to

understand the rise of Islamists clearly one should also look at the historical

mutation of the nature of the Turkish state. First, in Ottoman times, the

concept of a just ruler in people’s commonsense in an Islamic framework crafted

a space for Islamic politics. And during the republican times the initial

decision of the Kemalist elite to use Muslim brotherhood as a concept that

unites Kurds and Turks which at the same time excludes non-Muslim minorities,

inevitably created a dual role for religion both as a spiritual guidance and

the symbol of Turkish identity. Then references to Turkish people’s religious

identities resonated more widely than the intended purposes when the

politicians began to use it as a political tool to enlarge the legitimacy of

their dominant projects.

However, Turkey’s

Islamic movement, which grew as a subordinate to the neoliberal project of the

Turkish dominant classes, gained its political independence after the collapse

of the Soviet Union and the erosion of the ideological influence of socialdemocracy among masses. In the mid-90s ideological

attraction of Islam took a role of class critique when it organized around

shantytowns of urban areas by promising a just order against inequalities and

corruption, which they predominantly associated with Western-style capitalism.

At the same time Islam provided a useful network to the emerging exporters of

the conservative Anatolian bourgeoisie in their quest to enlarge their share

from the economic pie vis-à-vis the big bourgeoisie. Those opportunity structures

made the Islamic Welfare Party of Necmettin Erbakan a leading faction in the

parliament in the 1995 elections.

The Welfare Party’s

official performance in government and its non-reconciled critique of Western

cultural influences and the immorality of seculars in Turkey, and its

redistributive policies, which largely diverted resources to the emerging small

and middle-size businessmen in Anatolia within the general framework of

neo-liberalism created tension with the civil and military bureaucracy and

Istanbul-based big capital.

Even the largely

symbolic gestures of Erbakan to its conservative base became a sensational

media story that depicted those as potential threats to the secular republic.

However, under all these political tensions lay the class interests of the big

bourgeoisie and military, which in crisis times undertook the role of the

unified party of the bourgeoisie to smash the opposition.

As a result of

civilian and uniformed reactions against the Welfare Party government, Erbakan

resigned in June 1997 after the military forced him to strictly implement its

largely anti-Islamist 28 February ultimatum. That secular offensive both

broadened the base of the official Kemalist ideology among the public and

eroded the financial and economic power of the Islamist businesses. As the

Constitutional Court prosecuted the Welfare Party and its successor Virtue

Party on the grounds that they had become the focal points of anti-secular

activities, the young generation of reformists in the Islamic movement, led by

Abdullah Gul and Tayyip Erdogan, planned a break with the old guard of the

Islamist movement. The new AKP (Justice and Development Party) not only

pragmatically refuse to be categorized as a religious party but it also dropped

the decades-long Islamist references to social equality, anti-Westernism and

slogans like just order.

When AKP won the 2002

(and now again in 2007) elections with 34 percent of the vote they resembled a

conservative democratic party whose primary emphasis was human rights,

democracy, rule of law and Turkey’s quick integration with the Western

capitalism under IMF supervision. This new face of Turkey’s Islamist movement

can be interpreted as a pragmatic reconciliation with the old establishment in

order to create a breathing space for the weakened Islamic political and

economic forces. As their new pro-establishment line contradicted their

previous references to social equality, their class-based supporters in the

shantytowns became disillusioned with AKP’s economic performance. The question

remained: was their new rhetoric of democracy and decreasing the role of the

military within politics, this time with the backing of TUSIAD (big business),

sincere?

From past experiences

and how the Islamists interpreted democracy and the anti

establishment struggles of the left and the Kurds, we have great doubts

that we can rely on AKP to further the democratization of Turkey. Their

perennial emphasis on a morally higher way of life, an Islamic society, greatly

falls short of the demands of freedom of humanity from exploitation by its own

kind. A movement that sanctifies the basic tenets of capitalism today, getting

support from the emerging exporter businessmen of Anatolia, would hardly be a

panacea to the mountainous social and economic inequalities that the Turkish

people have to struggle with everyday.

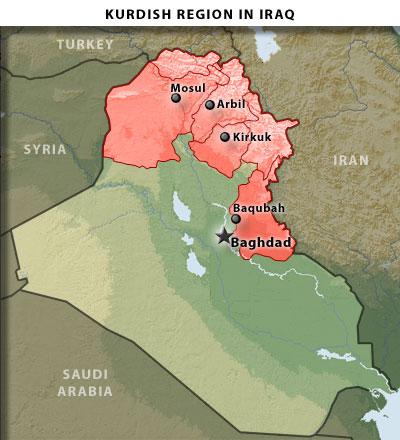

The reelection of

Erdogan in July 2007, however will also mean that a new offensive might be

launched to invade N.Iraq or so called Kurdistan.

The reelection of

Erdogan in July 2007, however will also mean that a new offensive might be

launched to invade N.Iraq or so called Kurdistan. Introduction:

Will Iran and Turkey soon invade N.Iraq? The initial

reason for such planning is because as we pointed out before

'Kurdistan' lowered the Iraqi flag on Sept. 2, 2006. However what may hasten up this development is an occurrence on Sept. 28, 2006. Thus where in the previous link we presented an in

depth report about the situation in Iraq as a whole, we now proceede

with a background-report about on ‘the other side’ of the border:

Kurds repeatedly

staged uprisings in Iraq and in adjacent regions of Iran. Typically they

launched rebellions when central government authorities appeared weak. Thus there

is a long history of Kurdish uprising during or immediately after wars. The

early uprisings were regional and tribal, but Kurdish revolutionary movements

became increasingly nationalist during the twentieth century. Mullah Mustafa

Barzani of the Barzani tribe of northeastern Iraq was the most famous of all

Kurdish revolutionaries. With his elder brother Sheikh Ahmad, he fought the

government of Iraq in an uprising in 1931 and 1932 that was suppressed with the

help of the Royal Air Force. In 1945 Barzani declared revolution but retreated

under Iraqi pressure to the town of Mahabad in northern Iran. Mahabad

flourished as a center of Kurdish nationalism during World War II after the

Soviet Union took control of northern Iran in 1941. The Republic of Mahabad

declared its independence in January 1946 but soon fell to Iranian forces, and

in 1947 Barzani retreated to the USSR. He returned to Iraq from exile in 1958

after a revolution that briefly led to improved relations between the central

government and Iraq's Kurds, but renewed fighting broke out in 1961. (Jonathan

C. Randal. After Such Knowledge, What Forgiveness? My Encounters with Kurdistan

(Boulder, Colo., 1999), pp. 112-131.)

Kurdish nationalism

developed a new intensity after the Baath party took control of Iraq in 1968.

At first the new regime in Baghdad, uncertain of its power, offered Kurds in

the north elements of self-rule, but the status of the city of Kirkuk and its oil

fields proved a major problem. Saddam Hussein's regime and Kurdish leaders

disputed whether Kirkuk would lie within the borders of a Kurdish region. In

1974 Baghdad unilaterally announced an autonomy measure that maintained central

control over Kirkuk. Barzani refused to accept these terms and launched his

last uprising. He depended on Iran for support, but Iraq concluded an agreement

with Iran in 1975 and defeated Barzani. (Human Rights Watch, Iraq's Crime of

Genocide: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds, 1995, pp. 4,19-20).

This was Mullah

Mustafa Barzani's final defeat-he died in 1979 in the United States. But in

1980 Iraq's invasion of Iran weakened the Iraqi military presence in Kurdish

areas and sparked renewed Kurdish revolution by two competing Kurdish parties,

the Kurdistan Democratic party (KDP) led by Mullah Mustafa's son Massoud

Barzani, and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan party (PUK) led by Jalal

Talabani.

The governments of Iraq

and Iran both employed selected deportations as a tool to suppress Kurdish

uprisings, but in Iraq deportation gradually developed into ethnic cleansing.

After suppressing Mullah Mustafa Barzani's final uprising, Iraq embarked on a

campaign to remake the population of parts of northern Iraq. The government

destroyed numerous Kurdish villages and provided incentives to Arabs to replace

Kurds. Sunni Arabs from the desert south of Mosul, for example, moved north

into Kurdish lands. As one Arab explained of his move into a Kurdish village in

1975, "We were very happy to go to the north because we had no irrigated

lands in the south." Meanwhile tens of thousands of Kurds were deported

south. In 1978 and 1979 Iraq cleared a zone of close to twenty miles along

areas of its northern border, and destroyed hundreds more Kurdish villages. All

told, Iraq pushed about a quarter of a million nonArabs,

including Kurds, out of their lands. (Human Rights Watch, Claims in Conflict:

Reversing Ethnic Cleansing in Northern Iraq, August 2004, vol. 16, no. 4 E, pp.

2, 8, 10; and Samantha Power, "A Problem from Hell": America and the

Age of Genocide, 2002, p. 175.)

Between 1987 and 1989

Iraq carried out an even more violent campaign against the country's Kurds. In

1987 Saddam placed his cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid in charge of retaking control

over Iraq's north, and in April Iraqi forces first used the weapon that would

give al-Majid the name that made him internationally notorious:

"Chemical

Ali." Iraqi forces released chemical weapons over Kurdish villages in the

valley of Balisan. They also destroyed hundreds of

villages. Peter Galbraith, a staff member for the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations

Committee, saw some of the destruction in September 1987. The Iraqi ambassador

to the United States offered to let Galbraith visit, and Iraqi forces

surprisingly allowed Galbraith and an American diplomat to continue on their

way into the Kurdish region where they found that most of the Kurdish towns and

villages along the road had been destroyed. (Human Rights Watch, Iraq's Crime

of Genocide, pp. 40-47, 49-51; Power, "A Problem from Hell," p. 183.)

The war against

Iraq's Kurds culminated in 1989 with the Anfal Operation in which Iraqi forces

burned villages, launched chemical attacks, and relocated Kurds. This was an

ambitious program of ethnic cleansing. AI-Majid described his goals in a tape

of an April 1988 meeting. "By next summer," he said, "there will

be no more villages remaining that are spread out here and there throughout the

region, but only camps." He spoke of prohibiting settlements in large

areas ana of mass evacuations: "No human beings except on the main

roads." The most infamous Iraqi gas attack of the Anfal Operation took

place on March 16 at the town of Halabja; many other towns and villages

suffered a similar fate. On the afternoon of May 3, 1988, Kurds at the village

of Goktapa, for example, heard the sound of Iraqi

jets. Goktapa had been bombed many times before, but

this time was different. As one witness recounted, "When the bombing

started, the sound was different from previous times. I saw smoke rising, first

white, then turning to gray. The smoke smelled like a matchstick when you burn

it. I passed out.” (Quoted in Human Rights Watch, Iraq's Crime of Genocide, pp.

255, 118; Power, "A Problem from Hell," pp. 188-189).

In all, Iraqi forces

killed about 100,000 Kurds during the Anfal Operation and forced hundreds of

thousands out of their homes. The final Iraqi campaign to remake the ethnic map

of the country's north followed immediately after the Gulf War of 1991. With

the Allied victory, Kurds staged a nationalist revolution and took over

virtually all of the Kurdish areas of northern Iraq. After reaching a

cease-fire, Saddam Hussein struck back against the Kurds. The fall of Kirkuk in

late March to Iraqi forces unleashed a wave of flight. More than a million

Kurds fled north. They crossed by the thousands over mountains to the border of

Turkey. The Turkish government did not welcome the refugees, though local Kurds

did what they could to provide food. One Kurdish baker in southeastern Turkey

increased his bread production more than threefold. "I don't know if it's

enough," he told a reporter. "But everyone from this area is

helping." (New York Times, April 7, 1991.)

This crisis so soon

after the Allied victory in the Gulf War gained international attention. Acting

on humanitarian grounds, the United States, Britain, and France created a

"safe haven" close to Iraq's northern border with Turkey and

established a "no-fly zone" for the Iraqi air force north of the

thirty-sixth parallel. By October 1991 Iraqi forces and authorities withdrew

from most Kurdish regions of Iraq's north with the exception of Kirkuk. The

effective division of northern Iraq into Kurdish and Iraqi zones simultaneously

advanced Kurdish interests and the Iraqi regime's campaign to Arabize the

north. Kurds gained autonomy, but the Iraqi government accelerated its campaign

to remake Kirkuk into an Arab city and region. Iraqi authorities deported 100,000

people from Kirkuk and other communities and encouraged Arabs to move north to

replace them.

Since then, the

Kurds, have been playing their cards carefully to ensure the advances they have

made since the 1991 Persian Gulf War were not lost in the web of negotiations

with the Shia and Sunnis after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. The Kurds opted

for a more gradual approach in securing their autonomy in northern Iraq,

realizing that an aggressive push for independence in the post-Saddam Hussein

era would only have invited a messy reprisal from Turkey.

Thus, even though it

was a priority for the Kurdish delegation to keep Kirkuk under the control of

the Kurdish regional government, the Kurds were willing to offer the concession

of allowing current oil revenues to filter through the central government in

Baghdad. Displaced Kurds who were driven out of Kirkuk by Hussein's forces in

his bid to "Arabize" the city are now returning; the Kurdish

leadership hopes they will constitute a majority in the December 2007 census,

so that a proposed referendum in the city will allow them to keep Kirkuk part

of the Kurdistan Autonomous Region legitimately. And Kurdish leaders do not

plan on disbanding the peshmerga, but will gradually integrate its guerrilla

forces into the state security apparatus.

Washington likely

will not endorse the Kurdish strategy fully. Kurdistan faces the dilemma of

having its territory spread across four countries -- Iran, Iraq, Syria and

Turkey -- each of which has a core interest in repressing its Kurdish minority

to dampen any separatist tendencies. For its part, the United States has

complex relations with each of these countries, and so cannot afford to promote

the existence of an independent Kurdistan in the region.

Washington's main

goal in the negotiations for the formation of Iraq's full-term government was

to bring the Sunnis into the political fold. This is aimed at quelling the

Sunni nationalist insurgency and bringing pressure to bear on the Sunni

jihadists.

For the Kurds, this

means a considerable number of obstacles lie in their path to regional

autonomy. Earlier, Abdel Aziz al-Hakim -- who leads the main Iraqi Shiite

political party, the United Iraqi Alliance, as well as the Supreme Council for

the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) -- loosely supported the Kurds in the

idea of regional federalism during the referendum negotiations. At that time,

the prospect of securing a Shiite enclave in the south looked promising.

While SCIRI, an

Iranian creation formed in Tehran in 1982, saw federalism as being in its

interest, Jaafari's Hizb al-Dawah and the movements

of al-Sadr and Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani are much more centered on a strong

central government. Thanks to the Shiite failure to achieve a consensus on the

notion of federalism, the Sunnis won a chunk of the government in the December

2005 elections. When Sunni participation in the election decreased their

influence, Shiite leaders joined al-Sadr's call for a strong central

government. They also openly opposed the Kurdish preference for a regional

federal structure, which essentially provides for an autonomous Kurdish region

in the north that would include all the provinces with sizable Kurdish

populations.

Given the complexity

of the negotiations, the most the Kurds can hope for at this juncture is a

political framework containing as many loopholes as possible to allow for their

continued evolution into a sovereign entity. Moreover, for Kurdish aspirations

to be met, the United States must maintain its military presence in Iraq to

keep regional forces in check. What is becoming increasingly clear, however, is

that Washington's interests in Iraq do not clearly align with Kurdish

interests.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(The books we used and often refer to in

the text):

Aglietta, Michael.1987.A Theory of Capitalist Regulation:

The U.S. Experience. London: Verso.

Ahmad, Feroz. 1969. The

Young Turks; the Committee of Union and Progress in Turkish Politics,

1908-1914. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

-------------1981.Turkey:

The Generals Take Over. Middle East Report. No 93, Jan 1981, 5-24.

Akcam,

Taner.2004. From Empire to Republic: Turkish Nationalism and the Armenian

Genocide. New York: Zed Books.

Akin, Erhan and Omer

Karasapan.1988. The Rabita Affair. Middle East Report, Issue No 153,

July 1988, 15-18.

Alymer,

Gerald.1975.The Levelers in the English Revolution. Ithaca: Cornell

University Press.

Anderson, Benedict.

1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of

Nationalism. London: Verso.

Aras, Bulent and Omer

Caha. Fettulah Gulen and His Liberal" Turkish

Islam" Movement, in Barry Rubin(ed).2003. Revolutionaries and

Reformers: Contemporary Islamist Movements in the Middle East. Albany:

State University of New York Press.

Arrighi

Giovanni.2003.The Belle Époques of British and U.S Hegemony Compared.

Politics and Society, Vol 31, No 2, 325-355.

Avcioglu, Dogan. 1981. Milli Kurtulus Tarihi

1838’den 1995’e. Vol 1 of 4 Volumes.Istanbul:

Tekin Yayinevi.

Ayata,

Ayse. Ideology, Social Bases, and Organizational Structure of the Post-1980

Political Parties, in Atilla Eralp, Muhharem Tunay, Birol Yesilada

(eds).1993. The Political and Socioeconomic Transformation of Turkey.

New York: Praeger

Ayata,

Sencer. The Rise of Islamic Fundamentalism and its Institutional Framework, in

Atilla Eralp, Muhharem

Tunay, Birol Yesilada (eds).1993. The Political

and Socioeconomic Transformation of Turkey. New York: Praeger.

Aydin, Zulkuf. The World Bank and the Transformation of Turkish

Agriculture in Atilla Eralp, Muhharem

Tunay, Birol Yesilada (eds).1993. The Political

and Socioeconomic Transformation of Turkey. New York: Praeger.

Balkan, Erol and

Erdinc Yeldan. Peripheral Development Under Financial

Liberalization:

The Turkish

Experience, in Sungur Savran and Nesecan Balkan

(eds). 2002. The Ravages of Neo-Liberalism: Economy, Society and Gender in

Turkey. New York: Nova

Barkey, Karen and

Ronan Van Rossem. 1997. Networks of Contention: Villages and Regional

Structure in the Seventeenth Century Ottoman Empire. American Journal of

Sociology. Vol 102, No5:1345-1382

Baskan,

Filiz. The Political Economy of Islamic Finance in Turkey: the Role of Fettulah Gulen and Asya Finans in Henry Clement and Rodney

Wilson (eds). 2004. The Politics of Islamic finance. Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press.

Bauman, Zygmunt.

1992. Intimations of Postmodernity. London, New York: Routledge

Beinin, Joel. 2001. Workers

and Peasants in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Berkes, Niyazi. 1975.

Turk Dusununde Bati Sorunu.

Ankara:

Bilgi Yayinevi.

Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal

Nationalism. London: Sage Publications.

Birtek,

Faruk, Caglar, Keyder. 1975. Agriculture and the

State: An Inquiry into Agricultural Differentiation and Political Alliances:

The Case of Turkey. Journal of Peasant Studies. Vol 2, No 1: 18

Birge, John. 1965. The

Bektashi Order of Dervishes. London: Luzac

Braudel, Fernand.

1972. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II.

New York: Harper& Row.

Brenner, Robert.1998.

The Economics of Global Turbulence. New Left Review, Issue No I/ 229,

1-265

Brewer, Anthony.1980.

Marxist Theories of Imperialism: a critical survey. London: Routledge.

Brockett, Gavin. 1998.

Towards a Framework of Social History of Ataturk Era. Middle Eastern

Studies. Vol 34, No4 (October): 44

Brown, John P. 1927. The

Dervishes or Oriental Spiritualism. London: Oxford University Press.

Bugra, Ayse.

Political Islam in Turkey in Historical Context: Strengths and Weaknesses, in

Sungur Savran and Nesecan Balkan (eds). 2002. The

Politics of Permanent Crisis: Class, Ideology and State in Turkey. New

York: Nova

--------------. 2002.

Labor, Capital and Religion: Harmony and Conflict among the Constituency of

Political Islam in Turkey. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol38, No2, 187-204.

Bulut, Faik. 1999. Tarikat Sermayesi 2:

Yesil Sermaye Nereye? Istanbul: Su Yayinlari.

Cakir, Rusen. 2002. Ayet ve Slogan: Turkiye’de Islami Olusumlar. Istanbul: Metis Yayinlari

Cinar, Menderes.

1997. Yukselen Degerler’in

Isadami Cephesi: MUSIAD.

Birikim, No 95, Mart 1997, 3-11.

Clay, Christopher. Economic

Expansion and Social Change: England 1500-1700.Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Clement, M.Henry, Rodney Wilson, (eds).2004. The Politics of

Islamic Finance. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Cohn, Theodore.2000. Global

Political Economy: Theory and Practice. Massachusetts: Longman.

Coskun, Bezen, 2003. The Triumph of an Islamic Party in Turkey.The Interdiciplinary Journal of International Studies. Vol 1,

No 1: 59-73

Cox, Robert. Gramsci,

Hegemony and International relations: An Essay in method in Stephen Gill (ed).

1993. Gramsci, Historical Materialism and International Relations.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

---------.1987. Production

Power and the World Order: Social Forces in the Making of History. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Cudsi,

Alexander S. 1981. Islam and Power. Maryland: The Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Culhaoglu, Metin. The History of the Socialist-Communist

Movement in Turkey by Four Major Indicators, in Sungur Savran and Nesecan Balkan (eds). 2002. The Politics of Permanent

Crisis: Class, Ideology and State in Turkey. New York: Nova

Dagi, Ihsan. Islamic

Political Identity in Turkey: Rethinking the West and Westernization. 2002.

Center for Policy Studies, Open Society Institute.

http://pdc.ceu.hu/archive/00001804/01/Dagi.pdf . Retrieved on July 2006.

------------.1998. Kimlik, Soylem ve Siyaset: Dogu-Bati

Ayriminda Refah Partisi Gelenegi.Ankara:

Imge Yayinevi Daldal, Asli. 2004. The New Middle Class as a

Progressive Urban Coalition: 1960 Coup d’etat in Turkey. Journal of Turkish

Studies. Vol5, No3 (Autumn): 75-102

Darling, Linda T.

1996. Revenue Raising and Legitimacy: Tax Collection and Finance

Administration in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Brill Academic Publishers.

Davison, Roderick H.

1963. Reform in the Ottoman Empire,1856-1876. Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

Dawn, Ernest.1991.

The Origins of Arab Nationalism, in Rashid Khalidi. 1991. Origins of Arab

Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deringil, Selim.1999. The Well Protected Domains: Ideology

and Legitimation of Power in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1909. New York: I.B.Tauris.

Eichengreen, Barry.1996. Globalizing Capital: A History of

International Monetary System. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Eley, Geoff. 1991. Reshaping

the German Right: Radical Nationalism and Political Change after Bismarck.

Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Emrence, Cem. 2003. Turkey in Economic Crisis1927-1930: A

Panoramic Vision. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol 39, No 4 (October): 67

Eralp,

Atilla. Introduction, in Atilla Eralp, Muhharem Tunay, Birol Yesilada

(eds).1993. The Political and Socioeconomic Transformation of Turkey.

New York: Praeger.

Ercan, Fuat. The

Contradictory Continuity of the Turkish Capital Accumulation Process: A

Critical Perspective on the Internalization of the Turkish Economy, in Sungur

Savran and Nesecan Balkan (eds). 2002. The Ravages

of Neo-Liberalism: Economy, Society and Gender in Turkey. New York: Nova.

Ergil,

Dogu.1975.Class Conflict and Turkish Transformation (1950-1975). Studia Islamica, No 39, 77-94.

---------.2000. Identity

Crisis and Political Instability in Turkey. Columbia Journal of

International Affairs. Vol 54, No1, 43-63.

Erturk, Husamettin.

1964. Iki Devrin Perde Arkasi.

Istanbul: Pinar Yayinevi

Fanon Frantz.1961. The

Wretched of the Earth. (www.marxists.org/fanon.)

Faroghi Suraiya. 1999. Approaching Ottoman History: An Introduction

to the Sources. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Findley, Carter V.

1980. Bureaucratic Reform in the Ottoman Empire: The Sublime Porte

1789-1922. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Friedman,

Thomas.1999. The Lexus and the Olive Tree. New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giraux.

--------. 12/1/1999.

His column in New York Times

Furet, Francois. 1981.

Interpreting the French Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gause, Gregory.1994. Oil

Monarchies: Domestic and Security Challenges in the Arab Gulf States.

Washington D.C: Council on Foreign Relations Press.

Gellner, Ernest.

1992. Postmodernism and Religion. London: Routledge.

Gibb, Hamilton and

Harold Bowen. 1957. Islamic Society and the West: A Study of the Impact of

the Western Civilization on Muslim Culture in the Near East. London: Oxford

University Press.

Gill, Stephen. Global

Hegemony and the Structural Power of Capital in Stephen Gill (ed) 1993. Gramsci,

Historical Materialism and International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

----------.1988. The

Global Political Economy: perspectives, problems and policies. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press.

-----------.1990. American

Hegemony and the Trilateral Commission. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Gilpin, Robert.2001. Global

Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gok, Fatma. The

Privatization of Education in Turkey, in Sungur Savran and Nesecan

Balkan (eds). 2002. The Ravages of Neo-Liberalism: Economy, Society and

Gender in Turkey. New York: Nova.

Gole, Nilufer.

Authoritarian Secularism and Islamist Politics: The Case of Turkey, in Augustus

Norton and E.J Brill (eds). 1996.Civil Society in the Middle East Vol2.London:

Leiden.

-------------.1996. Forbidden

Modern: Civilization and Veiling. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Gramsci, Antonio.

1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks, Trns

by Quintin Hoare. New York: International Publishers.

Gulalp,

Haldun. 2003. Whatever Happened to Secularization: Multiple Islams in Turkey.

Southern Quarterly, Vol 102 No 3, 381-395.

Haddad, Mahmoud.1991.

Iraq before the World War I: A Case of Anti-European Arab Ottomanism,

in, Rashid Khalidi. 1991. Origins of Arab Nationalism. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Halliday, Fred. 1996.

Islam and the Myth of Confrontation. Religion and Politics in the Middle

East. London: I.B. Tauris

------------.2002. Two

Hours That Shook the World: September 11, 2001: Causes and Consequences.London: Saqi Books.

Halman, Talat.2002.

Pir Sultan Abdal. His web page,

http://www.byegm.gov.tr/YAYINLARIMIZ/newspot/2002/sept-oct/n17.htm, Retrieved

on 15 May2005.

Hanioglu, M.Sukru.1995. The Young Turks in Opposition.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, David.1990.The

Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change.

London: Blackwell.

Helleiner, Eric. 1994. States and the Reemergence of Global

Finance: from Bretton Woods to the 1990s. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Heper,

Metin. 2000. The Legacy of the Ottoman Empire. Columbia University

Journal of International Affairs. Vol 54, No 1 ( Fall): 63-87.

Hill, Christopher.

1940. The English Revolution 1640. London: Lawrence& Wishart.

Hobsbawm, Eric.1992. Nations

and Nationalism since 1780: Program, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Howe, Marwine.2000.Turkey

Today: A Nation Divided over Islam’s Revival. Colorado: Westview Press.

Hunt, Lynn.2004. Politics,

Culture, and Class in the French Revolution. California: University of

California Press.

Huntington,

Samuel.1997. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order.

New York: Touchstone.

Ikenberry,

G.John.2001.After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and Rebuilding

of Order After Major Wars. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inalcik, Halil.1969. Capital Formation in the Ottoman

Empire. Journal of Economic History. Vol29, No1 (March):97-140

Inalcik Halil and Donald Quataert

(eds).1994. An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1914.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ipsirli, Mehmet.2004. Ottoman Ulema (Scholars).Foundation

for Science Technology and Civilization. p7 website

http://www.muslimheritage.com/uploads/OttomanUlema.pdf

Jameson,

Frederic.1991. Postmodernism or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.

North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Jessop, Bob. 2002. The

Future of Capitalist State. Cambridge: Polity Press

Joseph,

Jonathan.2002. Hegemony: A Realist Analysis. London: Routledge.

Kadioglu, Ayse. 1998. The Paradox of Turkish Nationalism

and the Construction of National Identity. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol 32,

No2 (April): 32

Kamel, S, Abu

Jaber.1967. Arab Bath Socialist Party: History, Ideology and Organization. The

Review of Politics, Vol 29, No4, 557-560.

Karaosmanoglu, Yakup Kadri. 1932. Yaban.

Ankara: MEB Yayinlari

Karpat, Kemal. 1968. Political and Social Thought in the

Contemporary Middle East. New York: Praeger.

Kasaba Resat. 1988. Ottoman Empire and the World Economy:

Nineteenth Century. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Kasaba Resat and Sibel Bozdogan. 2000. Modern

Turkish Identity. Columbia Journal of International Affairs. Vol 54,

No1,1-21.

Keyman, Fuat.

Globalization, Civil Society and Islam: The Question of Democracy in Turkey, in

J. Jenson and B.De Sousa Santos (eds).2000.Globalizing

Institutions. Ashgate: Aldershot.

Keynes, John M.1936.General

Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Mcmillian.

Khadduri, Majid.

1984. The Islamic Conception of Justice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Khalidi, Rashid.

1991. Origins of Arab Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kramer, Heinz. 2000. A

Changing Turkey: The Challenge to Europe and the United States. Washington

D.C: Brookings Institution Press

Krasner, Stephen.

2001. Problematic Sovereignty: Contested Rules and Political Possibilities.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Laciner, Omer. 1995. Postmodern Bir Dini Hareket: Fettulah Hoca Cemaati.Birikim.No 76, August 1995, 1-20.

Landau, Jacob.1982. The

Nationalist Action Party in Turkey. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol

17, No4, 587-606

Lewis, Bernard.2003. What

Went Wrong? The Clash between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East. New

York: Perrenial.

-----------------.1993.

Islam and the West. New York: Oxford University Press.

Maddison, Angus.1997.

Monitoring World Economy, 1820-1992.Review of International economics,

Vol 5, Issue4, 516-546

Mahirogullari, Adnan.1998. Turkiyede

Sendikalasma Evreleri ve Sendikalasmayi Etkileyen Unsurlar. C. U. Iktisadi Idari Bilimler Dergisi Cilt 2 Sayi 1, 161-191

Mardin, Serif. 1969. Power,

Civil Society and Culture in the Ottoman Empire. Comparative Studies in

Society and History. Vol11, No 3 (June): 258-281.

--------------.1962. Genesis

of Young Ottoman Thought: A Study in the Modernization of Turkish Political

Ideas. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Markoff, John.1996. Abolition

of Feudalism: Peasants, Lords, and Legislators in the French Revolution.

Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Marx, Karl. 1967. Capital;

A Critique of Political Economy. New York: International Publishers.

---------.1993. Grundrisse:

Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. London:Penguin.

Moore,

Barrington.1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and

Peasant in the Making of Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press.

Mortimer,

Edward.1982. Faith and Power: The Politics of Islam. New York: Vintage

Books.

Morton, Adam David,

Andreas Bieler (eds). 2001. Social Forces in the Making of New Europe: The

Restructuring of European Social Relations in the Global Political Economy.

New York: Palgrave.

Mumcuoglu, Maksut.1979. Sendikacilik

Siyasal Iktidar Iliskileri. Ankara: Doruk Yayinlari.

Narli,

Nilufer. The Rise of Islamist Movement in Turkey, in Barry Rubin(ed).2003. Revolutionaries

and Reformers: Contemporary Islamist Movements in the Middle East. Albany:

State University of New York Press.

O’Brien, Patrick

Karl. Britain 1864-1914 and the United States 1941-2001. Aldershot:

Ashgate.

Ohmae Kenichi.1990.

Borderless World. New York: Harper& Row

Onis, Ziya. 1997. The

Political Economy of Islamic Resurgence in Turkey: the Rise of the Welfare

Party in Perspective. Third World Quarterly. Vol, 18, October 1997, 740-758

-------------.2004.Turgut

Ozal and His Economic Legacy: Turkish Neoliberalism

in Critical Perspective. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol 40, No 4, 1-36.

Oran, Baskin.2001.Kemalism,

Islamism and Globalization: A Study on the Focus of Supreme Loyalty in

Globalizing Turkey. Northeastern and Black Sea Studies. Vol 1, No 3, 20-50

Othman, Ali. 1997. Kurds

and Lausanne Peace Negotiations, 1922-23. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol 33,

No 3 (July): 521

Owen Roger, 1981. Middle

East in the World Economy 1800-1914.London: Methuen

Owen, Roger and

Sevket Pamuk. 1999. A History of the Middle East Economies in the Twentieth

Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Oyan,

Oguz. From Agricultural Policies to an Agriculture without Policies in Sungur

Savran and Nesecan Balkan (eds). 2002. The Ravages

of Neo-Liberalism: Economy, Society and Gender in Turkey. New York: Nova.

Ozbudun, Ergun. Islam and Politics in Modern Turkey: the Case

of Salvation Party, in B.F, Stowasser (ed).1987. The Islamic Impulse.

Washington: Croom Helm.

Ozyuksel, Murat. 1993. Osmanlida

Feodalite. Bursa:

Bursa Uludag Universitesi Yayinlari

Palmer, Alan. 1992. Decline and Fall of the Ottoman Empire. New York: M.Evans and Co.

Panitch, Leo.1980. Recent

Theorizations of Corporatism: Reflections on a Growth Industry. The British

Journal of Sociology, Vol 31, No 2, 159-187.

Pamuk Sevket. 1994.

Money in the Ottoman Empire 1326-1914 in Inalcik

Halil and Donald Quataert (eds).1994. An Economic

and Social History of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

------- .1987. Ottoman

Empire and European Capitalism 1820-1913: Trade, Investment and Production. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

-----------. 1981. Political

Economy of Industrialization in Turkey. Middle East Report, No 93, Jan

1981, 26-32.

Pastor, Robert. 1980.

Congress and the Politics of U.S Foreign Economic Policy 1929-1976. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Patomaki, Heikki. 2001. After International Relations:

Critical Realism and the Reconstruction of World Politics. London:

Routledge.

Pijl,

Kees Van Der. 1984. Making of Transatlantic Ruling Class. London: Verso

Poulantzas, Nicos.1973. Political Power and Social Classes,

Trans, Timothy O’Hogan.London: NLB Sheed and Ward.

Prebisch, Raul. 1971. Change and Development—Latin

America’s Great Task, Report Submitted to Inter-American Development Bank.

New York: Praeger.

Redfield, Robert.

1956. Peasant Society and Culture: An Anthropological Approach to

Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Richards, Alan and

John Waterbury. 1996. A Political Economy of the Middle East. Colorado:

Westview Press.

Robinson, Richard.

1963. The First Turkish Republic; a Case Study in National Development. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press.

Robinson,

William.2001. Transnational conflicts: Central America, Social Change and

Globalization. London: Verso.

---------.2005. Gramsci

and Globalization: From Nation-State to Transnational Hegemony. Critical

Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, Vol 8, No4, 559-574.

Roshwald, Aviel. 2001. Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of

Empires: Central Europe, Russia and the Middle East, 1914-1923. London:

Routledge.

Ruggie,

John Gerrard.1996.Winning the Peace: America and World Order in the New Era.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Rupert, Mark. 2000. Ideologies

of Globalization. London: Routledge.

Quataert, Donald. 1979. The Economic Climate of the Young

Turk Revolution in 1908. Journal of Modern History. Vol 51, No 3

(September): 1147-1161. Sakallioglu, Umit Cizre.1996.Parameters

and Strategies of Islam-State Interaction in Republican Turkey. Journal of

Middle East Studies. Vol28, No2, 231-251.

Saribay, Ali Yasar.1985. Turkiyede

Siyasal Modernlesme ve Islam. Toplum ve Bilim No 29/30. 8-22

Schulze, Hagen. 1991.

The Course of German Nationalism from Frederick the Great to Bismarck

1763-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Savran, Sungur. The

Legacy of the 20th Century in Sungur Savran and Nesecan

Balkan (eds). 2002. The Politics of Permanent Crisis: Class, Ideology and

State in Turkey. New York: Nova.

Senesen, Gulay. Turkey’s

Globalization in Arms: The Economic Impact in Sungur Savran and Nesecan Balkan (eds). 2002. The Ravages of

Neo-Liberalism: Economy, Society and Gender in Turkey. New York: Nova.

Senses, Fikret.

Turkey’s Labor Market Policies in the 1980s against the Background of Its

Stabilization Program in Atilla Eralp, Muhharem Tunay, Birol Yesilada(eds).1993.

The Political and Socioeconomic Transformation of Turkey. New York:

Praeger.

Sluglett, Peter.1992. Tuttle Guide to the Middle East.

Boston: C.E Tuttle Co

Snyder, Louis Leo.

1978. Roots of German Nationalism. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press.

Stalin, Joseph. 1912.

Marxism and the National Question. (www.marxists.org/Stalin)

Taspinar, Omer. 2004.

Kurdish Nationalism and Political Islam in Turkey: Kemalist Identity in

Transition. London: Routledge

Tibi, Bassam. 1981. Arab

Nationalism: A Critical Enquiry. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Temin, Peter.1989. Lessons

from the Great Depression. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Thompson, Edward P.

1963. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books.

Toprak, Zafer. 1985. II.

Mesrutiyet Doneminde Paramiliter Genclik Orgutleri. Tanzimat’tan Cumhuriyet’e Turkiye Ansiklopedisi. Vol 1:

531-537

Tunay, Muharrem. The

Turkish New Right’s Attempt at Hegemony in Atilla Eralp,

Muhharem Tunay, Birol Yesilada

(eds).1993. The Political and Socioeconomic Transformation of Turkey. New

York: Praeger.

Turel, Oktar. The Development of Turkish Manufacturing Industry

during 1976-1987: An Overview, in Atilla Eralp, Muhharem Tunay, Birol Yesilada

(eds).1993. The Political and Socioeconomic Transformation of Turkey. New

York: Praeger.

Turgut, Hulusi. Fettulah Gulen ve Okullari. Yeni Yuzyil.31October 1998.

Tutengil, Cavit Orhan. 1964. Ziya Gokalp

Uzerine Notlar.

Istanbul: Varlik Yayinevi.

Uygur, Kemal. The

Meaning of May 27, in Kemal Karpat.1968. Political and Social Thought in the

Contemporary Middle East. New York: Praeger.

Van Dormael, Armand. 1978. Bretton Woods: Birth of a

Monetary System. London: Mcmillian.

Wallerstein,

Immanuel.1999. Historical Capitalism with Capitalist Civilization.

London: Verso.

Waltz, Kenneth.1999. Globalization

and Governance. PS Online, December 1999

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/walglob.htm.

Warde, Ibrahim.

Global Politics, Islamic Finance and Islamist Politics Before and After

september11, in Henry Clement and Rodney Wilson (eds). 2004. The Politics of

Islamic Finance. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Webb, Michael. 1999. The

Political Economy of Policy Coordination: International Adjustment since 1945.

Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

White, George E.

1918. Alevi Turks of Asia Minor. Moslem World. Vol 8, No 3: 242-248.

Wolf, Martin. Why

this Hatred of the Market? In Lecher and Boli (eds). 2000. The Globalization

Reader. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Vergin, Nur. 1985. Toplumsal Degisme ve Dinsellikte Artis. Toplum ve Bilim,

No 29/30. 31-55.

Yalman, GalipL. The Turkish State and Bourgeoisie in Historical

Perspective: A Relativist Paradigm or Panoply of Hegemonic Strategies? in

Sungur Savran and Nesecan Balkan (eds). 2002. The

Politics of Permanent Crisis: Class, Ideology and State in Turkey. New

York: Nova.

Yavuz, M.Hakan. 2000. Cleansing of Islam from Public Sphere.

Columbia Journal of International Affairs. Vol 54, No1, 21-43.

Yegen,

Mesut. 1999. Devlet Soyleminde Kurt Sorunu. Istanbul: Iletisim Yayinlari

Yeldan,

Erdinc. The IMF-Directed Disinflation Program in Turkey: A Program for

Stabilization and Austerity or a Recipe for Impoverishment and Financial Chaos?

In Sungur Savran and Nesecan Balkan (eds). 2002. The

Ravages of Neo-Liberalism: Economy, Society and Gender in Turkey. New York:

Nova.

Yenigun, Halil Ibrahim. 2003. Islamism and Nationalism in

Turkey: An Uneasy Relationship. www.virginia.edu/politics/grad_program/print/wwdop-2006-paperyenigun.pdf

. Retrieved on May 2005.

Yildizoglu, Ergin. 1988. The Political Uses of Islam in

Turkey. Middle East Report, Issue No 153, July 1988, 12-17.

Zubaida, Sami. 1993. Islam

The People &The State: Political Ideas and Movements in the Middle East. London:

I.B. Tauris&Co.Ltd.

Zurcher, Eric Jan.

2004. Turkey: A Modern History. New York: I. B. Tauris.

------. 2000. Ataturk

(Review Essay). Middle Eastern Studies. Vol 36 No 3(July): 253

For updates

click homepage here