This three-part study

will concern Roman von Ungern-Sternberg who

represents a revealing illustration of what was at stake in the re‑conquest and

stabilization of Central Eurasia. Whereby we also will see that what challenged

the rule of the Bolsheviks most vehemently was not the credo of the state

nationalists under the Russian White generals, who aspired to nothing other

than the immediate restoration of the “one and indivisible Russia”, but rather

the plans of a warlord, which in regard to the prevailing realities were

equally as daring as their own. The difference was not about megalomaniac

delusions of grandeur but lay rather in the totally different political goal

envisioned. Ungern‘s obsession, namely to be able to

establish a Greater Mongolian Empire, entailed turning away from the center; it

meant drawing the borders entirely anew in the East.

But first, a few

oddities I came across in the course of researching Unger who among his

present-day admirers is dubbed the Got of War which

in its initial historical context, of course, was a reference to Genghis Khan.

The myth and reality of Roman von Ungern-Sternberg

Eurasianism, a nearly century-old ideology, has taken hold in the

region following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, with Putin a strong

proponent. Originally formulated as a counter to Communism, Eurasianism

posits a Russian national identity based not on politics but on geography and

ethnicity, and it portends a stark and troubling future reality for Eastern

Europe. Alexander Dugin’s Eurasianism,

in turn, is best understood as an offshoot of the European Far Right, and not a

product of Russia’s distinctive cultural heritage.

Published in December 2007 “The Last Wargod”

(Der letzte Kriegsgott) the

nouvelle droite publication in question contains among others a

leading article, by Eurasianist Alexander Dugin, which titles Ungern von

Sternberg "the Got

of War" (Der Gott Des Krieges).

Alexander Dugin

even went as far as to claim that there existed a secret order named “Agharta” among the Russian Military Intelligence Glavnoje Razvedyvatel’noje Upravlenije -GRU. (For this reference see:

http://www.harrimaninstitute.org/MEDIA/00747.pdf)

Connecting Robert von

Ungern-Sternberg born in Austria,to

some form of Agartha myth—was initially invented by Ossendowski

in Beasts, Men and Gods (1922).

This wasn’t Ossendowski’s first literary fraud, as historian Gearge F. Kennan has pointed out he was also co- creator of

the so called “Sisson documents”.

Here Ossendowski wrote, that he convinced Ungern

of his story and that subsequently, Ungern sent

missions to seek Agharta. Selling three hundred

thousand copies within a year of its initial publication, Sven Hedin however,

discovered that the source of three of Ossendowski’s

chapters could be found within the pages of the occultist Saint Yves d’Alveydre, Mission de l’Inde en Europe. (Sven Hedin, Ossendowski and the Truth,1925).

Sable, further

contends that Ungern designed his war plans,

based on astrological charts that local Buddhist monks made for him. When Ungern realized however that the charts in question showed

a heaven as seen from Tibet yet did not depict the physical stars as seen

from Mongolia-- Unger started to experience doubt. Whereby in Mongolia itself,

some people are said to be still looking for the “ treasure” Ungern is believed to have stolen--and secretly buried.

Ossendowski wrote in, Beasts, Men and Gods, that he had heard

tell in Mongolia of a subterranean realm of 800 million inhabitants called

"Agharti"; of its triple spiritual

authority "Brahytma the King of the World,"

"Mahytma," and "Mahynga,"

its sacred language "Vattanan," and many

other things that seemed to corroborate Saint-Yves. The book ended on a somber

note of prophecy from one of Os send ow ski's

informants; that one day (the year 2029, to be exact) the people of Aghardi [sic] would issue forth from their caverns and

appear on the surface of the earth. (Ossendowski,

1922, p.314).

Although Buddhist’s

texts never described Shambhala as an underground kingdom, the portrayal by

Saint-Yves and Ossendowski, clearly parallel the

Kalachakra account of the Kalki ruler of Shambhala

coming to the aid of the world to end an apocalyptic war.

In 1927 French traditionalist Rene Guonon published a

description of “Agarttha” in Le Roi du Monde (The King of the World). In

1929 the Russian Nicholas Roerich published an account of Agharti

in the book, Altai Himalaya: A Travel Diary.

Note that Although Buddhist’s

texts never described Shambhala as an underground kingdom, the portrayal by

Saint-Yves and Ossendowski, clearly parallel the

Kalachakra account of the Kalki ruler of Shambhala

coming to the aid of the world to end an apocalyptic war.

Ungern

occupies the central section of Ossendowki’s book-one

of the "men" described after the "beasts" (the Reds from

whom Ossendowski had escaped), who come before the

"gods" (otherwise the Mongolian lamas with their peculiar variant of Budhism--see below). It also remains probable that Ossendowski indeed, met Ungern-Sternberg.

Ossendowski writes that it is a hidden land somewhere in the

East, below the surface of the earth, where a population of millions is ruled

by a "Sovereign Pontiff" of Ethiopian race, styled the Brahmatma. This almost superhuman figure is assisted by two

colleagues, the "Mahatma" and the "Mahanga".

His realm, Saint-Yves had explained, was transferred underground and concealed

from the surface-dwellers at the start of the Kali- Yuga, which he dates around

3200 BCE. Agartha has long enjoyed the benefits of a technology advanced far

beyond our own: gas lighting, railways, air travel, and the like. Its

government is the ideal one of "Synarchy"

(sometimes erroneously confused with Fascism) which the surface races have lost since the schism

that broke the Universal Empire in the fourth millenium

BCE, and which Moses, Jesus, and Saint-Yves strove to reinstate. Now and then

Agartha sends emissaries to the upper world, of which it has perfect knowledge.

Not only the latest discoveries of modern man, but the whole wisdom of the ages

is enshrined in its libraries, engraved on stone in Vattanian

characters. Among its secrets are those of the relationship of soul to body,

and of the means to keep departed souls in communication with incarnate ones.

When our world adopts Synarchical government, the

time will be ripe for Agartha to reveal itself and to shower its spiritual and

temporal benefits on us. To further this, Saint-Yves includes in the book open

letters to the Queen of England, the Emperor of Russia, and the Pope, inviting

them to use their power to hasten the event.

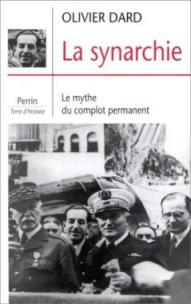

It was however Olivier Dard,

who pointed out the term synarchy was actually borrowed from J. A. Vaillant's:

work The Magic Key of Fiction and Fact (Clef magique

de la fiction du fait), Vaillant, just like Saint-Yves would later do, defined synarchie in opposition to anarchy, arguing that the principles

of synarchie must shape the social," which in

turn would shape the “religion of the future.” Another favored term of

Saint-Yves, Agharta, he borrowed from the fantasist

writings by Louis Jacolliot.

Any unprejudiced

reader, finding in three chapters of Ossendowski's

book a virtual precis of the "Agarttha"

described in Mission de l'Inde-not omitting the most

improbable details-would conclude that he simple capped an already good story

by altering the spellings-- so as to make his version, if challenged-- seem

informed by an independent source. But Ossendowski

denied this indignantly, asserting in the presence of Rene Guenon that he had

never even heard of Saint-Yves d'Aiveydre before

1924. Guenon's interest was kindled, and in 1925 he wrote that he had no reason

to doubt Ossendowski's sincerity. (Guenon, Le Roi du Monde. Les Cahiers du Mois 9/10:

Les Appels de I'Orient, Paris: Emile Paul Freres, 1925,p. 210).

More than that,

Guenon was moved to write his own book on the subject and its ramifications,

which appeared in 192 7 as Le Roi du Monde (The king of the world). He began by

saying that "independently of Ossendowski's

testimony, we know from quite different sources that tales of this kind are

current in Mongolia and all of Central Asia." (Guenon, Symbolism of the

Cross. Trans. Angus Macnab. London: Luzac, 1958,p.9).

Thus in 1927, Guenon

lend his support to a the so called “Polaires” They

had a so called ‘oracle’ (meaning a spiritualist medium) and in Bulletin des Polaires, 9 June 1930, they explained:

The Polaires take this name because from all time the Sacred

Mountain, that is, the symbolic location of the Initiatic

Centers, has always been qualified by different traditions as

"polar." And it may very well be that this Mountain was once really

polar, in the geographical sense of the word, since it is stated everywhere

that the Boreal Tradition (or the Primordial Tradition, source of all

Traditions) originally had its seat in the Hyperborean regions. (Jean Parvulesco, Les mysteres de la villa

"Atlantis." Paris: Guy Tredaniel, 1989, p.83).

For a mouthpiece of

the spiritual center of the whole earth, associated if not identified with

Agartha, the Oracle fell sadly short of expectations. Its answers were

elaborate, but not always conclusive. For example:

Q. Do the Three

Supreme Sages and Agarttha exist?

A. The Three Sages

exist and are the Guardians of the Mysteries of Life and Death. After forty

winters passed in penitence for sinful humanity and in sacrifices for suffering

humanity, one may have special missions which permit one to enter into the

Garden, in preparation for the final selection which opens the Gate of Agarttha. (Zam Bhotiva

[Cesare Accomani] “Asia Mysteriosa” Paris: Dorbon Aine, 1929, p.86).

Guenon wrote that he

had been interested, because he had tested the medium in question, by posing certain

doctrinal questions. (Guenon in Le Voile d'Isis,

February 1931).

Others who accepted

the oracle's authenticity are Arturo Reghini and

Julius Evola. In fact the December 2007 “The

Last Wargod” mentioned at the start, also contains a

(re-published) article by Julius Evola.

Oliver Dard also

aptly points out that the term Agharta it self might go back to the inspirations Ernest Renan

caused, when he wrote about “Asgaard” in central

Asia.

Ernest Renan, whose

book Life of Jesus 1863 (said to have inspired Notovich’s Eurasian version) wrote elsewhere:

A factory of Ases [Scandinavian heroes], an Asgaard,

might be reconstituted in the center of Asia. If one dislikes such myths, one

should consider how bees and ants breed individuals for certain functions, or

how botanists make hybrids. One could concentrate all the nervous energy in the

brain. It seems that if such a solution should be at all realizable on the

planet Earth, it is through Germany that it will come." (Renan, Dialogues

et fragments philosophiques. Paris: Calmann-Levy, 1876, P.117,120).

If this is the

independent source Guenon and Ossendowski might have

discussed together is an open question, however it would not impossible to have

impressed Julius Evola when he gave Ossendowski and Ungern-Sternberg

a second look (published in the above mentioned Dec.2007 “Junges

Forum”).

Evola

in fact took Geunon's "King of the

World" thesis one step further by producing his own "Revolt Against

The Modern World"(1934). Evola ellaborated on the same topic in an article that was

translated in German and published there in 1934/35 titled" The Swastika

as a Polar Symbol" (Evola, Das Hakenkreuz als polares Symbol, in

"Hochschule und Ausland" 1934/35).

Repeating what he explained in Revolt Against The

Modern, now in German

translation, that the polar star ("Polarstern")

is the Budhist Chakravartin (meaning

"King of the World").

Incidently Evola who proposed an

Italian SS based on "The Legion of

the Archangel Michael "

(Iron Guard) in Rumania which Evola admired, briefly drew the attention of Heinrich Himmler.

But what else do we know about Unger himself?

His relative-bymarriage Hermann Keyserling, later to become an important

figure in European occultism, observed that even as a young man Ungern was interested in 'Tibetan and Hindu philosophy' and

spoke of 'geometrical symbols'.Keyserling thought him

'one of the most metaphysically and occultly gifted men I have met'. (Hermann

Keyserling, Reise durch die

Zeit [A Journey through Time], vol. II ,Vaduz, I948, p. 53).

During the time Ungern lived in St Petersburg, there were thirty-five

officially registered occult groups in this one city alone. Then, as now,

alternative medicine was a mainstay of such movements, including a school of

'Tibetan medicine', frequented by the rich and gullible. And St Petersburg

bookstores (displaying windows, at the train stations) at the time,

contained books about spiritualism, chiromancy, and occultism. Also The

Theosophical Society after H.P.Blavatsky was in Adyar

is claimed to have had many thousands of followers in Russia that time--

mostly from the upper classes. In fact where an interest in both Eastern

religion and the occult tends today to be associated with a broad range of

'alternative' thought, and in general with radical, or at least mildly

left-wing, politics. This was not the case in Ungern's

time.

Among the Russian and

German aristocracy, belief in clairvoyance, poltergeists, telepathy,

spiritualism, astrology and the like were as common as belief in homeopathy

among the English middle classes today. Come the revolution, interest had

reached such a level among the White diaspora that priests in the

Russian-Chinese city of Harbin complained of being overwhelmed by Theosophists.

Blavatsky's books

occasionally leap into vivid, poetic passages, but exhibit for the most part a

tedious, prolix quality, replete with a high degree of pseudo-scholarship. A

touch of irony may be found where she writes of one of her invented verses of

the 'Secret Doctrine' that 'this is, perhaps, the most difficult of the stanzas

to explain. Its language is comprehensible only to him who is well versed in

Eastern allegory and purportedly obscure phraseology'.

But Theosophy was

normally presented in Russia as a form of Buddhism - Theosophical circles

frequently opened 'Buddhist temples' - and Ungern

certainly perceived it as such. His term for his own faith, 'esoteric

Buddhism', echoed a phrase which recurs throughout Blavatsky's writings, and

was a standard description for Theosophy in Russia. The influence of

Theosophical language and ideas is evident whenever Ungern

discusses religion. Of particular importance to Theosophists was a belief in

the 'Hidden Masters of the World' - great spiritual figures who influenced the

world through their mystical powers, and whose benevolent teachings and

guidance could aid the West. They communicated through Madame Blavatsky,

apparently by dropping envelopes in the corners of rooms while nobody was

looking through a sort of mystical postal service.

Tied into the notion

of the positive conspiracy of the Hidden Masters was its inverse; the negative,

manipulating, corrupting influence of evil forces. The notion of a

conspiratorial elite could be traced back, in part, to a confused

misinterpretation of the Jewish belief in thirty-six 'righteous men', living

and suffering saints for whom God continued to spare the universe from

destruction. Unsurprisingly, this rapidly became tied in with the

conspiratorial anti-Semitism of Jewish well-poisoners, bankers and

revolutionary masterminds. Western occultism had often exhibited a

traditionally philo semitic

streak, but now it was almost as though the Wisdom of the East had come to

replace the Wisdom of the Jews, the Kabbalah swapped for Tibetan magic.

Although mainstream

Theosophy was not obsessed by conspiratorial anti-Semitism, Blavatsky was never

averse to taking occasional sideswipes at Judaism. She wrote of it as

'theologically a religion of hate and malice towards everyone and everything

about it'. In contrast to Aryan religion, 'the Semite interpretations emanated

from, and were pre-eminently those of a small tribe, thus marking [ ... ] the

idiosyncratic defects that characterise many of the

Jews to this day - gross realism, selfishness, and sensuality'. Not to mention

that 'while the Egyptian emblem was spiritual, that of the Jews was purely

materialistic'.

Theosophical ideas of

the rise and fall of races and peoples meshed well with another popular Russian

mystic and philosopher, Konstantin Leontiev, known as

the 'Russian Nietzsche'. Although he died when Ungern

was five, his books, particularly Russia and Europe, were still popular. They

were exaltations of Russian character and will, in contrast to the weakness and

softness of the West. Cultures began in simplicity and purity, became more

intricate and entangled, and finally, burdened by their own complexities,

decayed and died. Western society, with its unnatural commitment to

egalitarianism rather than natural, healthy difference, was doomed. Leontiev praised the East, particularly its nomadic

peoples, and felt that Russia's destiny lay with expansion into Asia. For now,

Russia could be preserved by keeping everything exactly as it was - 'frozen so

it doesn't stink' - and by the vigorous power of the tsar's will.

Monarchy-dictatorship was the way forward. Ungern

absorbed his ideas, and would regurgitate some of them later, along with those

of other mystical and reactionary thinkers.

Combined with this

was a sense of the slow sinking of the 'Evening Land' of the West. This would be put most powerfully by thinkers such

as Oswald Spengler in The Decline of the West (1917) and the Prussian

philosopher Moeller van den Bruck, a Russian-speaker obsessed with the coming

rise of the East. Both called for Germany to join the 'young nations' of Asia -

through the adoption of such supposedly Asiatic practices as collectivism,

'inner barbarism' and despotic leadership. The identification of Russia with

Asia would eventually overwhelm any such sympathies, instead leading to a

more-or-less straightforward association of Germany with the values of 'the

West', against the 'Asiatic barbarism' of Russia. This was most obvious during

the Nazi era, when virtually every piece of anti-Russian propaganda talked of

the 'Asiatic millions' or 'Mongolian hordes' which threatened to overrun

Europe, but identification of the Russians as Asian - and especially as

Mongolian - continued well into the Cold War era.

It was not an

identity that most Russians shared. The East was the other, the opposite of civilised, Westernised Russia,

and the Mongols the epitome of the Asian bogeyman. Nikolas II was just as

concerned about the threat of the 'yellow' peoples as his cousin, and it had

shaped Russia's actions during the war with the Japanese. Nevertheless, some Russians,

particularly artists, were becoming increasingly interested in the Mongolian

heritage of the country. Russian intellectual identity was continually torn

between Asia and Europe, both wanting to be part of European, 'civilised' culture and feeling the call of 'wild Asian

blood'. Most of the time the first view prevailed, and the whole history of

Russian-Mongol relations was rewritten into a myth of heroic resistance, the

extensive collaboration between Russian kingdoms and the Mongols forgotten. The

Mongols became the enemy - but at the same time they represented something

heroic and wild, a romantic part of the Russians' self-image and yearning.

As a result, in the

nineteenth century there was an increasing trend in Russia towards

'pan-Mongolism', a search for the origins of Russian customs and folk beliefs

in Asiatic legend. This rested mainly upon a nebulous and romanticised

image of Mongolia in which Mongols, Tatars and Scythians were bundled together

into a vision of untamed and savage natural life. Serious interest in the

cultures and religions of the Far East was limited to a tiny minority of

ethnologists, linguists and hobbyists. There were also those who needed

practical knowledge, the soldiers and bureaucrats who protected and governed

Russia's far-flung eastern provinces, although they often arrived with a

pre-forged image of the peoples and territories they were about to encounter. Ungern was soon to be numbered among them.

His was a romantic

version of what was, in fact, an entirely pragmatic approach towards the

Russian borderlands. Like most imperial peoples, the Russians soon realised that it was easier to co-opt than coerce. They

lacked the numbers to try the Chinese or American approach to dealing with

areas dominated by minority ethnic groups; open up the borders, encourage (or

coerce) hundreds of thousands of your own people to settle the region and

outnumber the locals within a generation or two. With the borderlands so

strategically crucial, they had to be secured another way. Membership in the

Russian Empire had to be made attractive, particularly to the local elites. Old

tribal structures and religious hierarchies were maintained, but were

incorporated into the imperial bureaucracy. As a result Russian officials found

themselves deciding obscure questions of tribal inheritance, or determining

whether a new visionary religion among the Oirat

Mongols threatened imperial stability, or funding the construction of Buddhist

temples. Local leaders or priests were paid off with lucrative government jobs

or posts in the army. If these tactics failed, though, imperial policy could

demonstrate a Roman ruthlessness, crushing rebellious tribes and salting their

fields.

The Buriat provide a good example of the ambiguous attitude of

the Russian Empire towards its ethnic minorities. On the one hand, it had

conquered and (theoretically) subjugated them, and the majority of ethnic

Russians maintained profoundly racist attitudes towards the various Asian

peoples. Russian settlement had driven some, particularly the various Siberian

tribes, away from their traditional territories, brought disease and stripped

them of their traditional independence. On the other hand, the empire had a

vested interest in keeping the Buriat and other large

groups happy. In many ways they had more rights than the average Russian - they

paid less tax, they were exempt from conscription, IS they were able to keep

their traditional leadership. Many of the Asiatic minorities were actually more

privileged than the Ukrainians and Poles, who were forbidden even from using

their own languages. The Asiatic minorities benefited from their very

foreignness. The Western minorities were seen as a plausible target for JZussification, but the Mongol-descended peoples, far more

ethnically and religiously distant, were left to their own devices.

The empire remained

focused around its Great Russian and religiously Orthodox core, but at the same

time was able to embrace numerous diverse groups at its edges. Sometimes

members of these groups could be the most ardent proponents of imperial

expansion. For instance, the Buriats' place within

the empire was made even more secure by the rise to power and influence of one

of their compatriots, Piotr Badmaev. A convert to

Orthodoxy and practitioner of Tibetan medicine, he had the ear of both Alexandr III and Nikolas II, and considered himself the

protector of the Buriats. He also pushed for plans,

never realised, to expand the empire yet further,

annexing Tibet and parts of western China.

With the exception of

his time in St Petersburg, Ungern's whole life was

spent on the fringes of the empire. They would come to define the Russian

Empire for him, even when its core was abandoned, but his idealistic vision of

it didn't make the mundane work of guarding its frontiers any less boring.

He had chosen to join

a cavalry division not onJy for its glamour but also

because he loved horses. The Buriat, like their

Mongolian cousins, were excellent riders and good judges of horseflesh. Ungern was already a talented rider, but under the tutelage

of more experienced officers his skills improved further. He soon mastered the

art of mounted combat and became respected in the regiment for his riding

skills. Warfare on horseback has a romanticism which has not quite disappeared

from the Western consciousness, and Ungern would

remain enthusiastic, to his later tactical disadvantage, about the

possibilities of the cavalry charge and the lightning raid. He had other

diversions too; one report mentions his interest in 'general' as well as

'military' literature and European philosophy.

Again it was Hermann

Keyserling, a fellow Baltic noble, who wrote that he had a strong impression of

Ungern:

certainly the most remarkable person I have ever had the good fortune to meet.

One day I said to his grandmother, Baroness Wimpfen,

'He is a creature whom one might call suspended between Heaven and Hell,

without the least understanding of the laws of this world.' He presented a

really extraordinary mixture of the most profound aptitude for metaphysics and

of cruelty. So he was positively predestined for Mongolia (where such discord

in a man is the rule), and there, in fact, his fate led him. [ ... ] He was not

of this world, and I cannot help thinking that on this earth he was only a passing

guest.1

As Ungern passed into Mongolia he was riding through an

otherworldly environment. Sometimes on the grasslands he could look in any

direction and see no human sign all the way to the horizon, the blue of the sky

like a vast ocean above him, broken only by the flicker of a bird of prey.

Unless he ran across herders, or saw a marmot scurrying briefly above ground,

the world would seem entirely devoid of life. The empty landscape was similar

to that of Siberia. Perhaps he even found comfort in being only a speck on a

vast expanse of nothingness - he never had great need of any company other than

his own.

Not all of Mongolia is

flat, particularly in the north-east, and much of the time he would have been

travelling through long stretches of hills, rising sometimes into mountains,

across swamps, or between thick forests where humans rarely intruded. Small

clusters of rocky hills broke up the open countryside, as though the earth had

been punched from beneath. Ungern regarded the

landscape with a tactician's trained eye, looking for routes that a cavalry

army could take; he could still remember them a decade later. Such terrain was

also attractive to the builders of monasteries, the only permanent structures

in most parts of Mongolia, the steep slopes and commanding views being

excellent defensive features. Here travellers could

find rest and safety; the monks were often trained fighters and the monastery

walls thickly reinforced. Ungern would have been made

welcome, for the monks paid little heed to race or religion and usually

accepted Chinese, Russian and Mongolian visitors alike - a laudable generosity

given the fact that the preceding few hundred years had seen several Chinese

invasions of Mongolia, and many monastery-fortresses, which had been centres of resistance, had been either burnt down or

stuffed with gunpowder and blown up. Destroyed monasteries were not the only

ruins Ungern would have encountered; he might have

stumbled upon remnants of pre-Mongol civilisations,

perhaps the Ozymandian palace of a long-forgotten

Turkic king. In the summer heat herds of horses pressed themselves against the

old walls, or gathered under the rare bridges, desperate for shade.

Ungern

could not have carried enough food and water to survive the entire journey

self-sufficiently, so must have relied upon the everyday hospitality of the

Mongolians. Mongolia's harsh terrain and climate, particularly in the winter,

meant that feeding and housing travellers was

considered a duty by every household. Even a foreigner would be given shelter

for the night unquestioningly, and food for the next day. Ungern

must have spent many nights in the cramped and dark interior of a Mongolian

tent, with a barrel of fermented mare's milk by the door and the family

sleeping on cushions inside. He must also have seen the regular devotions of

the Mongols, sprinkling offerings to the spirits and praying to the gods and Buddhas.

As a foreigner

travelling alone he would have drawn special attention from the locals. Many

European visitors to Asia liked to wear traditional dress, often writing

self-flatteringly that they were indistinguishable from the locals. This seems

hard to believe. Even today, any European male in rural China, regardless of

dress, draws a crowd of openmouthed children, middle-aged women cheerfully

assessing his looks and young men shouting 'Hello!' There were only a few

hundred Europeans in the whole country at the time, among perhaps a million

Mongolians; apart from the small Russian settlement around the consulate in Urga, which was the sole foreign enclave, they were

guaranteed to attract attention from the locals, curious as to what exotic

items or powerful magic they might possess. (Europeans were seen by many

Mongols as being potentially powerful sorcerers. The explorer Henning Haslund described how a young woman had come to him and

begged him to symbolically 'adopt' her sick baby, since his powerful 'white

man's magic' would be able to drive away the spirits that plagued the child. He

went through the ritual, and the child promptly recovered.) A traveller would never be without company, however

unwelcome.

Ungem

would certainly have stood out among the Mongolians, with his bullet-shaped

head, stage-villain moustache and tufts of reddishblond

hair. He was in first-rate physical condition, lean and hard, but when he spoke

his voice varied wildly in pitch, like that of a teenager, although he was

almost thirty. Aleksei Burdukov,

a Russian merchant, fell in with Ungem for a while.

He left an unforgettable picture of him: 'a scrawny, ragged, droopy man; on his

face had grown a wispy blond beard, he had faded, blank blue eyes, and he

looked about thirty years old. His military uniform was in abnormally poor

condition, the trousers being considerably worn and torn at the knees. He

carried a sword by his hip and a gun at his belt.'2 Ungern

rode alongside Burdukov's coaches, a skilled,

tireless horseman, shouting at the coachmen when he felt they were slacking and

striking them with his whip. When the group stumbled into a swamp, Ungern 'laid on the ground and refused to move, listening'.

Then, going forward and ordering the others to follow, he led them from patch

to patch through the bog, 'finding the most convenient solid places with

surprising dexterity and often getting into knee-deep water'. Eventually he

sniffed at the air, 'seeking the smell of smoke to find nearby settlements. At

last he told us one was nearby. We followed him, and he was right - in the

distance we heard the bark of dogs. This unusual persistence, cruelty,

instinctive feelings amazed me.' Burdukov despaired

of the quality of young Russian officers in the country, if Ungern's

bad manners and cruelty were typical of the breed.

The first thing Ungern possibly would have noticed about Urga, Mongolia's most populous settlement, was the smell.

Sewers were as unheard of as electricity, and human waste was simply thrown

into the streets to be devoured by the packs of scavenging dogs that roamed the

city. Anybody venturing outdoors at night took a stick to beat off the animals,

but their main enemies were the hordes of beggars, mostly old women no longer

able to bear the rigours of steppe life, driven to

the town to live a few last miserable years fighting with the dogs for scraps.

To add to the stench, the Mongolians were a notoriously unwashed people,

believing the rare springs and streams in the country were home to territorial

spirits who would inflict dreadful illness on trespassers.

Ungern

arrived there in the autumn of 1913, but it was a strangely timeless city;

apart from the rifles sometimes carried by hunters and soldiers, and the very

occasional European motor car, it would have been hard to tell whether it was

1913 or 1193. Merchants rode in on camel or horse from China, bearing silks,

drugs and teas; trappers hawked furs that would eventually be sold for a

thousand times their initial price when they reached Moscow or London;

fortune-tellers cast oracle bones on the street to determine the fates of young

nobles.

It was a trading

city, where Mongols, Chinese and Russians met to exchange goods worth over a

million dollars a year. Its Chinese and Russian enclaves were well established,

almost entirely separate from the Mongolian one. Urga

lay at the centre of the Tea Road, the overland route

to Russia, and originally the local currency had been bricks of tea, but now

most traders preferred the brass cash of the Chinese, or even Mexican dollars

(a common trading currency at the time). The markets were full of livestock,

enlivened by the occasional Western wonder such as a gramophone or a camera,

normally brought for the amusement of the ]ebtsundamba

Khutuktu, also known as the Bogd

Gegen, Holy Shining One, Holy King or Living Buddha:

the ever-reincarnating head of the Mongolian Buddhist orders and one of the

very few Mongols who could afford such toys) It was the closest that Mongolia

had to a capital, being the nominal centre of the

most dominant Mongolian group, the Khalkha,4 but the real power lay in foreign

hands. Mongolia had been under Chinese control for three centuries, and the

Chinese administration, including a small garrison, was based in Urga.

Primarily, it was a

city of religion. Out of the roughly twenty-five thousand permanent Mongolian

residents, an estimated ten thousand were either monks or had some sort of

affiliation with the monasteries. There were a hundred and three reincarnated

lamas in Mongolia, returning life after life, and many of them lived there. Urga had been founded in the seventeenth century as the Ikh Khuree, or 'great monastery',

to serve as the residence of the Bogd Gegen, and that remained its Mongolian name; 'Urga' was used only by Russians and other foreigners.

Temples were everywhere, dark and smoky, statues of their gods concealed in

numerous alcoves. The gods were usually depicted in a warlike stance,

brandishing weapons and trampling on corpses, but some were joined together in

elaborate and implausibly athletic couplings, no doubt to the ribald amusement

of the more elderly and worldly-wise female pilgrims) The statues were dressed

by the temple's monks, some of whom would climb, agile as monkeys, over the

larger examples, sometimes twenty metres tall, in

order to change a goddess's scarf or repaint a cracked face. Most of the monks

wore the conventional saffron robes of Buddhism, but some wore heavy wooden

masks depicting the angry or ecstatic faces of the gods, dancing and singing in

their honour. Yellow silk banners fluttered in the

breeze outside the temples, emblazoned with the swastika, an ancient symbol of

Buddhism and one particularly venerated by the Mongolians.

Being a monk was a

relatively good life, compared with that of herder, scratching out a bare

subsistence and ever fearful of a bad zud, a peculiar

local combination of hard winter and quick-melting frost that could kill a

quarter of the country's livestock. The vast majority of Mongolians lived as

nomads, moving between camps according to the seasons and relying on their

animals to survive. Monks were certain of a full bowl and a comfortable place

to sleep, if nothing else, and the temples were major money makers, storing

most of what wealth there was in Mongolia. The temples were visible for miles,

since they were the only large buildings in Urga;

most of the population lived in gers (felt tents).

Important gers were surrounded by walled compounds,

marking an uneasy compromise between settled and nomadic life. Only in the

Russian compound and the Chinese trading town of Maimaichen,

a few miles from the main city, were permanent buildings common.

Throughout the year

the population of the city would be bolstered by pious pilgrims, bringing

offerings of food, money and incense. By local standards, Urga

was a major site of religious tourism, sometimes drawing Buddhists from China

and Tibet as well as from all the Mongol tribes. The Gandan

Temple, the residence of the chief Mongolian oracles, was the most visited

location, a steep and shadowy building designed to induce a suitable degree of

fear and trembling in the approaching supplicant. The Bogd

Khan's own palace, a couple of miles away, was a two-storeyed

European-style affair, painted in lurid shades of green and yellow and greatly

venerated. Today it seems a modest building, on the same scale as a decent

sized English farmhouse, but it was the first building in Mongolia to have more

than one floor, and pilgrims would come to see the miracle of its staircase,

treading gingerly upon each step.

Religion was not the

only amusement. The 'three manly sports' of wrestling, horse-riding and

archery, the foundations of the Mongolian's old military might, were hugely

popular. Men of all ages would come to compete against each other at

tournaments, and informal matches were common; travellers

reported young men racing on horseback through the city, or two bear-like

amateur wrestlers grunting and shoving against each other in the street as

their wives watched and cheered. The 'three manly sports' were really five;

drinking and boasting were considered equally important.6 The Mongolian

assertion that 'every man is Genghis Khan in his own tent' was surely heard as

widely then as today, and if all the drunken claims of beasts slain, Chinese

humiliated and women wooed were true, Mongolia was a nation of heroes.

Religious ceremonies,

frequent and extravagant, were at the core of life in the city. At festival

times the perimeter could expand to four or five times its normal size,

acquiring a huge outer ring of gers and becoming a

great campground with the city at its centre. New

buildings would be hastily constructed to bear enormous statues or

prayer-flags; rows of lamas danced through the streets; crowds cheered and

clapped and prayed. Festivals were times of masks: skull-masks for the dancers

of death, demon-masks stuck on poles to grin eerily in the sunlight like from

Chinese control, and proudly proclaimed Mongolia free, strong and Buddhist.

The revolution had

been a painful affair. In China, the Qing dynasty was finally collapsing after

a drawn-out agony of more than a century during which China's rulers had proven

woefully unprepared to deal with Western guns, opium or ideas. The few Chinese

remaining in Mongolia, mostly officials and merchants, had no stomach for a

fight, especially in the name of a foreign dynasty. There were just over a

hundred Chinese troops in Urga facing four thousand

Mongolian soldiers and perhaps a thousand Russians. The worst fighting had been

in the west, around the city of Khobdo, where Mongol

forces stormed the Chinese compounds and slaughtered the garrison. Other

resistance leaders led small bands against the Chinese elsewhere in the

country; one of the most successful was formed by Togtokh,

a Mongolian prince and long-standing opponent of the Chinese, who headed a

group of warriors equipped with Russian rifles.

The Qing themselves were not Chinese but Manchu. A nomadic and warlike group of northern clans

unified under the charismatic leadership of Nurhaci, much as the Mongols had

been under Genghis Khan, they had conquered China in I644, driving out the

reigning Ming dynasty. The Mongol leaders loathed the Ming, who were descended

from the leaders of the original Chinese rebellion against the Mongols, and

were only too happy to see the Qing take the throne, swiftly sealing deals

whereby the leaders of each Mongol clan effectively accepted Manchu rule. (So

happy, in fact, that the southern Mongol tribes of modern Inner Mongolia

acknowledged the first Qing emperor as the 'great khan' in 1636, eight years

before the final conquest of China, although it took another sixty years for

the northern Mongols to accept Qing leadership.) The early Qing emperors took

wives from among the Mongols, particularly those who could prove direct descent

from Genghis, in order both to strengthen their ties to Mongolia and bolster

their claim to be the true heirs of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and so the

legitimate rulers of China. They also spread rumours

that they had discovered the legendary Great Seal of Genghis Khan, legitimising their reign through prophecy.9

The greatest

challenge to the Qing came from the Zunghar kingdom

of western Mongolia, led by the powerful and charismatic leader Galdan Khan, who also made claims to legitimacy through

descent from Genghis. Its power was destroyed by a century of Qing campaigns,

combined with outbreaks of smallpox which killed 40 per cent of the population.

Continued Mongolian resistance resulted in the Chinese adopting a policy of

genocide in the I750s, effected by starvation tactics and an imperial order 'to

take the young and strong and massacre them'. Siberian governors reported

refugees' stories of Manchu troops massacring entire settlements. Roughly one

hundred and eighty thousand people were killed, and the survivors fled to join

the Kazakhs and Buriats in Russia. 'For several

thousand Ii [around 600 miles],' reported one

historian, 'there was not one single Zungharian

tent'.10

Despite the devastation

wrought by the Qing in the west, many Mongolians were content to live under

Manchu rule. The Manchu were determined to keep their original homelands in the

north free from corrupting Chinese influence, and so banned all settlement in

both Manchuria and northern Mongolia. They issued a series of decrees in the

nineteenth century which forbade Mongols from learning the Chinese language,

taking Chinese names, adopting Chinese clothing and habits, or even eating

Chinese food. Population pressures resulted in widespread settlement by Han

Chinese in southern Mongolia, which had effectively been absorbed into China by

the beginning of the twentieth century and today is the modern-day province of

Inner Mongolia. The breakdown of the non-settlement policy, combined with

incompetent administration and the stranglehold that Chinese traders had on the

Mongolian economy, kindled anti-Qing feelings among the Mongols. By 1911

demonstrations, rebellions and attacks on Qing officials were becoming

increasingly common. Debt and natural disaster drove a growing number of former

nomads into a pitiful life as beggars on the edge of the towns.

The communist regime

was later to claim the 1911 rebellion as a precursor to Mongolia's glorious

Marxist uprising. That the Mongols had petitioned Russia for support in their

revolution made good communist propaganda, and it has been called Asia's first

modern revolution. In truth there was very little modern about it. Democratic

ideals were current among a tiny fraction of the Mongolian population, mostly

those lucky few who had worked or been educated in Russia or China and who had

picked up ideas from reformers there. The instigators of the petition to Moscow

comprised a small circle of young hereditary nobles, determined to regain some

measure of their ancient power. The heads of each Mongol tribe had been

obliged, under the Qing, to visit Peking to make obeisance to the emperor, and

any who failed to do so were forced to pay tribute in sheep to his

representatives in Mongolia.

This rankled the

nobles, whose ancestral memories of the mighty Yuan dynasty of Genghis Khan were still vivid. Back then the 'proper' order of things had been

established and the Chinese had paid tribute to the Mongols, not the other way

round. Life had at least been tolerable so long as the Qing had maintained

their distinctly Manchu, nomadic identity, but resentment against them

increased as they became more Sinicised. The Manchu

language, which bore some similarity to Mongolian, had been almost completely

abandoned by the Qing except for ceremonial purposes and they had become

virtually indistinguishable from the Han Chinese. Even their hairstyles were

identical, for the Han had been forced to adopt the pigtail among several other

Manchu customs.

The rebellion

mustered considerable popular support, not so much from any great liking for

the nobles as from distaste for the Chinese. In order to placate dissenters at

home and defend against Russian expansionism, the Chinese authorities had begun

allowing much greater colonisation in Mongolia. They

stationed two regiments in Inner Mongolia in 1906 and began the construction of

a railway to compete directly with the Russian line. Over twenty thousand

square miles of land had been taken away from the Mongols for the Chinese

settlers to farm, and three hundred and fifty thousand Chinese settlers had

moved into Inner Mongolia.

All these measures

were resented by the Mongols, especially Chinese colonisation.

The Mongolians, still almost entirely herders and nomads, valued their land and

their space more than anything else, and saw urban life as essentially soft,

fit only for beggars and monks. The Chinese merchants and bankers were resented

most of all; the Mongols, increasingly impoverished by colonisation

and Qing taxation, were forced to buy on credit, often at crippling rates of

interest. Chinese merchants were the main target of the outbreaks of violence

during the revolution; over three hundred of them were murdered and their debt

records burned in ceremonial pyres on the streets.

Anti-Chinese feelings

were even more intense in Inner Mongolia, where the call for Mongolian

independence was eagerly taken up by the eight Mongol clans there, all of whom

were suffering badly from Chinese expansionism. One of the largest groups was

the Chahars - so prominent, in fact, that one

province, which encompassed much of modern Inner Mongolia, was named after

them. They held territory around the Chinese city of Chengde and were particularly

fierce in their opposition to Chinese rule, but Han settlers outnumbered them

by a ratio of nearly I9 to I and many Mongols were driven over the border into

northern Mongolia or Russia.

The superior attitude

of the Chinese towards the Mongolians didn't help matters. In the Chinese

suburb of Urga, Maimaichen,

the people lived in wooden buildings instead of gers

and kept their distance from the Mongolian city. Mongolia was the edge of the

Chinese Empire, and the colonists harboured the usual

prejudices against the natives. Themselves stereotyped by the British and

Japanese as lazy, backward, cruel and ignorant, the Han Chinese applied their

own sets of prejudices to the northern barbarians. Nineteenth- and early twentiethcentury Chinese accounts consistently portray the

Mongols as scurrilous, lazy and drunken - sometimes accurately, especially in

respect of the town-dwelling Mongols they encountered most often - and this

attitude seems to have carried over into everyday dealings between the two

groupings.

The Mongolian

reputation for cruelty, insensibility and stupidity, a legacy of the ruthless

conquests of the hordes, still survived in both Asia and Europe. Chinese

popular dramas featured Mongolian henchmen, often Oddjob

to Japanese Blofeld, who habitually threatened the

hero or heroine with sadistic tortureY A later but

telling example comes from the Second World War, where one French doctor,

witnessing the execution of a Mongolian prisoner, a member of a German

repression unit (perhaps lent by the Japanese; perhaps drafted by the Russians,

then captured and drafted again12) spoke of how 'he had no thoughts at all

about what was happening to him. He had died as an animal does'.13

Medically speaking,

Down's syndrome children were 'mongoloid', a term originally intended to

reference not only their epicanthic eyes, but also their diminished mental

capacity. Western visitors remarked upon the Mongolians' 'remarkable naivety'

or 'child-like attitudes'. The Chinese mocked them as dumb, smelly barbarians,

and took remorseless advantage of their (quite genuine) gullibility in matters

of trade. One Briton commentated sniffily, 'Ch'ou

Monks who preached against him rarely survived their dinner invitations.

According to Ossendowski, 'The Bogd

Khan knows every thought, every movement of the Princes and Khans, the

slightest conspiracy against himself, and the offender is usually kindly

invited to Urga, from where he does not return

alive.'17 Those who declined were usually later found strangled. One notable

banquet, given for a group of Tibetan emissaries from the Thirteenth Dalai

Lama, who, no political slouch himself, was uncomfortable with his supposed

underling's debauchery and independence, ended with all the representatives

perishing that very night. He could be more direct: a monk who drunkenly

wondered aloud, 'Is that miserable old blind Tibetan still alive? What do we

call him our king for? I don't care a fig for his orders and admonitions' was

executed for blasphemy. 18 To us it might seem that the spirit of an especially

degenerate Borgia had entered the Bogd in some kind

of terrible metaphysical mix-up, but in fact such murderous tactics were hardly

unusual in the cut-throat politics of Buddhism.

The Bogd was the son of a monastic Tibetan administrator in

Mongolia. Recognised at four as the new incarnation

of the Bogd Khan, he would have been all too aware of

being surrounded by enemies. Reincarnated lamas retained their possessions

between lives, but until they came of age these were in the hands of their regents.

Consequently, many met with fatal accidents before they reached adulthood - the

Thirteenth Dalai Lama, the Bogd Khan's contemporary,

was the first to make it to his thirties in nearly a century.

Those who did survive

faced a lethal combination of Buddhist theological and temporal politics. The

history of Tibetan Buddhism is a corrupt and Byzantine affair, seemingly tailor

made to suit old-fashioned anti-clericalism. It is like I, Claudius with silk

scarves: in every scene somebody is either poisoned, stabbed, caught in

flagrante or shoved over a cliff. The Fifth, or Great, Dalai Lama established

himself as the ruler of Tibet chiefly through the exile, disgrace or murder of

most of his opponents, and some of the Bogd Khan's

previous selves had shown a similarly direct approach to their opposition.

His paranoia and

taste for power went along with a desire to add to the material possessions he

had accumulated over the course of several lives. In this incarnation they were

frequently supplemented by expensive imports from America, Britain and China.

'Motorcars, gramophones, telephones, crystals, porcelains, pictures, perfumes,

musical instruments, rare animals and birds; elephants, Himalayan bears,

monkeys, Indian snakes and parrots - all these were in the palace of "the

god" but all were soon cast aside and forgotten.'I9 His macabre collection

of stuffed animals; puffer-fish and penguins and elephant seals may still be

viewed, laid out in a back room of his palace. Sadly, the mirrors with 'intricate

drawings of a most grossly obscene character'20 have been removed. His zoo was

particularly infamous, including giraffes, tigers and chimpanzees preserved in

a miserable half-life of cruel teasing and desperate cold. One unfortunate

elephant had to walk to Urga from the Russian border,

a three-month tramp. He valued human oddities, too; the elephant was looked

after by Gongor, a seven foot six inch giant from

northern Mongolia.

Despite the Bogd's dubious ethics and repellent appearance, most

European visitors were rather charmed by him. Some claimed to find in him a

true example of the duality of Buddhism, embracing both good and evil. Others

found him an amusing and witty conversationalist, knowledgeable about political

dealings in China and Russia. Ungern's relationship

with him would be half-wary, half-worshipful, although in 1913 he had no

inkling that his path would eventually bring him into the closest contact with

the 'great, good Buddha'.

Soviet accounts would

later claim that after Ungern was 'cashiered from the

army' he was driven to a life of crime, forming a group of brigands that preyed

on Russian and Chinese alike. This was certainly not the case - apart from the

lack of any evidence, it was the kind of thing Ungern

would have boasted about, or at least used to enhance his credibility with the

Mongols. Among the Russians, claims of Ungern's

achievements became equally exaggerated. He was 'the commander of the whole

cavalry force of Mongolia', 21 claimed one of his later superiors. In fact, his

journey in 1913 left little trace in the historical record. And he was not the

only Russian interested in the country.

The Russian

government was only too happy to provide aid to the new Mongolian government,

which had approached them as early as July 1911, six months before the actual

expulsion of the Chinese. By December 1912 there were treaties of mutual aid

and support in place. The humiliation of the Russo-Japanese war still smarted,

and Korea and Manchuria were, at least for the moment, outside the Russian

sphere of influence, but Mongolia was a perfectly plausible option. China, weak

and backward, was a much easier target than Japan, and Mongolia, while neither

rich nor populous, was a perfect location for a base to exert further influence

on the region. Relations between China and Russia were customarily peaceful,

thanks to the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1687, which had

ended twenty years of border conflicts and neatly divvied up north-east Asia

between them. Yet the opportunities for expansion as China's border territories

started to fall apart had been too good to miss, and Russia had extorted

considerable land concessions in the nineteenth century. Mongolia was merely an

extension of this policy.

Consequently Mongolian

independence, while given no outright backing from Moscow, was tacitly

encouraged from 1905 onwards. The Russians began to compete in earnest against

the Chinese, building their own railway through Mongolia and dropping

none-too-subtle hints to the nascent independence movement that they might find

Russian aid in their time of need. A small-scale trade war began between

Russian and Chinese merchants, both competing to offer the most favourable terms to their Mongolian suppliers. Although

they rejected an initial approach by the Mongolians, their policy soon changed

when it became apparent that the Chinese had neither the power nor the troops

to keep control of Mongolia.

In the long run, the

Russians had no interest in Mongolian independence. Aleksei

Kuropatkin, the general responsible for the farce of

the Russo-Japanese war and leader of a clique at court dedicated to Asian

expansion, wrote that 'in the future, a major global war could flare up between

the yellow race and the white. For this purpose, Russia must occupy north

Manchuria and Mongolia. Only then will Mongolia be harmless. '22

Kuropatkin's words perhaps indicate another source of Russian

anxiety about Mongolia; a deep-rooted memory of the Mongol conquests that gave

this otherwise minor country a greater importance. His real worry, though,

concerned the waves of Chinese immigration into Manchuria and Inner Mongolia,

which he and other military and politicalleaders saw

as 'the first blow of the yellow race against the white' the 'Yellow Peril'

feared throughout Europe. Indeed, in European eyes the Mongols often stood in

for the whole of Asia, over-breeding and posing a constant threat to Western civilisation. In the pseudo-science of racial hierarchies,

'Mongol' was used for the whole of East Asia, and the spectre

of Genghis Khan was raised time and time again during the early twentieth

century, especially as Japan began its rise to power; convenient shorthand for

the 'Yellow Peril' as a whole.

One party in the

Russian government seriously considered annexing Mongolia outright in 1912, but

more cautious voices prevailed. Instead they would arm and train the new regime

as a buffer against China. In the summer of 1912, then, the Russians dispatched

a small group of military advisers to train the Mongolian army, some twenty

thousand strong but completely unskilled in modern warfare. Many of the troops

didn't even have guns, preferring the composite bow, taut and powerful, that

dated back to Genghis Khan's mounted archers, and military discipline had

become a foreign concept. Under Genghis and his immediate successors, the

Mongolians had been a more streamlined, disciplined and deadly war machine than

any army until the Second World War, but nothing of this remained; now the

emphasis was on individual glory, outdoing rival clans, and plunder. They

needed to be licked into shape, and the Russians had the men for the job.

Ungern

latched on to them, attempting to get himself a post with the Russian garrisons

in Urga and the western city of Khobdo,

both of which contained members of his former regiments. He was refused, but

found himself attached to the Khobdo guard as a

supernumerary captain. With few actual duties, he spent his time studying the

language (he would scribble down new words he came across), practising

his riding and talking to the lamas and monks who dominated the Mongolian

cities. The other officers found him strange and off-putting, and effectively

excluded him from their society. One witness remembered him sitting alone in

silence much of the time, and on other occasions being seized by a strange

spirit and leading whooping Cossacks in wild charges across the plains.

He may have had some

contact with one of the most legendary lamas, Dambijantsan,

also known as the Ja Lama. This mysterious figure had been fighting against the

Chinese for over thirty years; he claimed to be the great-grandson, and later

the reincarnation, of Amursana, a famous

eighteenth-century fighter against the Manchus who was in turn a purported

incarnation of Mahakala, the Great Black God, a

ferocious deity who, like the other 'dharma protectors', shielded Buddhists

from the enemies of the faith. Popular memory maintained a series of classic

'hidden king' legends around him, and his eventual return to liberate the Western

Mongols (the Oirats) from Chinese domination. In

reality Amursana had been, at times, a collaborator

of the Manchus, but this was conveniently forgotten. Critically, Amursana's place of magical concealment, from which he

would soon emerge, was in Russia - the ever-mystical north, where he had died

while under Russian protection in 1757. By making his claims, then, Dambijantsan sought to legitimise

himself dynastically, through Amursana's nobility,

politically, by assuming the mantle of anti-Chinese resistance, and

theologically, by claiming the magical inheritance of Amursana

and the incarnated power of Mahakala. As an epic poem

written in his voice put it:

I am a mendicant monk

from the Russian Tsar's kingdom, but I am born of the great Mongols. My herds

are on the Volga river, my water source is the Irtysh. There are many hero

warriors with me. I have many riches. Now I have come to meet with you beggars,

you remnants of the Oirats, in the time when the war

for power begins. Will you support the enemy? My homeland is Altai, Irtysh, Khobuk-sari, Emil, Bortala, and Alatai. This is the Oirat mother

country. By descent, I am the great-grandson of Amursana,

the reincarnation of Mahakala, owning the horse Maralbashi. I am he whom they call the hero Dambijantsan. I came to move my pastures back to my own

land, to collect my subject households and bondservants, to give favour, and to move freely.23

These were grand

claims for a squat, ugly monk, but his charisma and his military success

gathered many followers. Ungern had learnt about him

from Russian and Chinese newspapers, and probably from the travelogues of the

Russian ethnologist and political agent Aleksei Pozdneiev, who collected stories of him in the 1890s, and

hoped to join him to fight against the Chinese, but was forbidden from doing so

by his superiors. Khobdo had seen fierce fighting

only that year between Mongolian fighters and the Chinese garrison, and the

Chinese fortress had fallen in a scene of bloody revenge.

The Ja Lama had been

at the forefront, politically and militarily, of these battles; he was, as Ungern aspired to be, a near-legendary figure of militant

Buddhism. After he seized western Mongolia, although he claimed to still be

loyal to the Bogd Khan, he ruled autocratically for

more than two years. The atrocities at Khobdo were

typical of his regime. There were plausible accounts, both from his enemies

and, later, from former allies, that he conducted a ritual, upon taking the

fortress, in which the hearts of two Chinese victims were literally ripped from

their chests, like victims of an Aztec sacrifice.24 The rumour

that his ger was lined with the skins of his enemies was probably false, but

other lamas reported that he used terror ruthlessly. If Ungern

met the Ja Lama, he found him a disappointment - he had sung his praises before

his arrival in Mongolia, but referred to him only in disparaging terms

afterwards - though he must also have drawn many lessons from him.

Throughout his later

career in Mongolia, Ungern professed nothing but respect

for Buddhism and 'the destiny of the Buddhist peoples'. 25 It was on this trip

that he learnt the importance of these beliefs among the Mongolians. It was a

strikingly, almost fanatically, Buddhist country, hence the power of the Bogd Khan. No matter what his sins, the Bogd's

theological status - and his political clout - were beyond question. What we

observe so often, and what seems so strange at first, is the fear and awe that

the Mongolian temples created, both in ordinary Mongolians and even in those,

like Ungern, raised in an utterly foreign tradition.

Mongolian Buddhism

hinged on sacrifice. The Mongolian gods were demanding, and unmoved by anything

except offerings. Although the merciful bodhisattvas did feature in Mongolian

religion, they could be overshadowed by the more uncaring deities. Offerings

were made for the usual reasons: relief of illness, fertility of crops, cursing

of enemies. Averting disaster also loomed large as a pious motive. Tibetan

Buddhism makes very specific distinctions between offerings for worship, which honour the enlightened gods, and offerings of propitiation,

made to keep the unenlightened gods from getting angry. Many Mongolian

offerings fell into this second category; payoffs to various malevolent spirits

in a divine protection racket.

A cynic might say

that this protection racket benefited corporeal lamas more than spiritual gods.

Every year, a significant part of the national income drained into the coffers

of monasteries already stuffed with the wealth of centuries. Another goodly

portion went, quite literally, up in smoke, for holocausts were an integral to

Mongolian ritual. Animal sacrifice was common, hecatombs of livestock being

offered to the blood-hungry gods. The meat, as with most offerings, ended up

feeding the monks - or sometimes the poor.

The lamas were

greatly concerned with sacrifice themselves. The Bogd

Khan's failing eyesight was a particular worry; ten thousand statues of the

Buddha were ordered from Poland, and a gigantic statue of the Buddha brought

from Inner Mongolia and placed in a newly built temple. Together these two

offerings, both made in I912, cost some 400,000 Chinese silver taels, a vast

sum of money. They had no effect on the Bogd's

vision.

And behind all this

there was always the whiff of something older and perhaps more frightening.

Mongolian Buddhism, like Tibetan, drew heavily on older religions, particularly

shamanism. The Chinese had their shamanic traditions too, but they were largely

corralled and suppressed, surviving only in a few figures such as the ancient

Mother Goddess of the West and the shape-shifting heroes of primordial Chinese

mythology. They are uncomfortable figures, standing somewhat outside the

comfortable domesticity or light bureaucratic satire of most Chinese gods. Even

today they have an unnerving power. In Hong Kong I once handled a statue of a

snake-god who, in ancient Chinese mythology, shaped the formless chaos of the

newly created universe.26 It caught my attention because they are so rarely

depicted directly, but it was long and thin and sinuous and seemed to twist

oddly in the half-light.

Western writers have

been fascinated by shamanism, in Asia and elsewhere, seeing in it the dawn of

religion. In Mongolia, it seemed, one barely had to scratch the surface of

Buddhism to uncover essentially shamanic beliefs. Indeed, some of the more

remote tribal groups still had shamans of their own. In shamanic cosmologies,

the spirit world is ever-present, and the rituals and sacrifices needed to deal

with it a mainstay of everyday life. The shaman stands between two worlds,

pleading or bargaining with the spirits for power for himself and his

community. Much of the Mongolian relationship with their gods seemed to be

drawn from this worldview, and the gods themselves were, in many cases, of

pre-Buddhist origin. The range of gods and spirits was highly varied; broad

distinctions could be made between the lu or nagas, spirits of water, the savdag,

spirits of land, and dashgid, the Wrathful Ones,

spirits of air, but within these there were numerous subcategories - nagas, for instance, could be categorised

by colour, origin, caste, intention and sex - and

only the lama or shaman could be expected to have the nous to deal with them

properly.

Tibetan Buddhism made

this explicit in its legends, telling of how early Buddhist saints had

wrestled, argued, or, in a few notable cases, seduced the demons of the land

into becoming good Buddhists. The myths weren't as explicit in Mongolia, but

the links were clear. Some gods were even regarded as having not yet found the

true path of Buddhism, and so could not be worshipped, but merely propitiated

with offerings, kept sated in order to avoid their vengeance. The bloody

iconography of Mongolian deities grew out of this ancient legacy. Buddhist

theologians, particularly those trying to promote the religion in the West,

have manfully tried to co-opt the corpses and skulls and bloodstained weapons

into images of peace and salvation. Their efforts - 'The corpse being trampled

beneath his feet represents the death of the material world' are unconvincing.

Gods were frequently

taken from Hinduism and turned into demons, a folk memory of old, and often

extremely violent, conflicts between Hinduism and Buddhism in India.27 The

pleasantly domestic elephant-headed Indian deity Ganesha

is depicted in Mongolian art as a hook-tusked, ferociously red demon, often

shown crushed beneath the feet of Buddhist warrior deities.

Even the enlightened

gods had their dark sides. The gentle female deity Tara had her wrathful aspect

of Black Tara, benevolent smile turned to gnashing fangs, long fingernails

turned to claws. Even more terrible was Palden Llamo, one of the divine protectors of Buddhism but also a

devouring mother who sacrificed her own children. She rode upon a lake of

entrails and blood, clutching a cup made from the skull of a child born from

incest, her thunderbolt staff ready to smash the unbelievers and her teeth

gnawing on a corpse. Her horse's saddle was made from the flayed skin of her

own child, who had become an enemy of the faith, and snakes wound through her

hair. Like many gods, she bore a crown of five skulls and a necklace of severed

heads. Her ostensible purpose was to defend Buddhism against its enemies, and

in particular to guard the Dalai Lama, but she must have terrified many true

believers as well. The Tibetans considered Queen Victoria to be one of her

incarnations. Nicholas II of Russia, in conttrast was

considerred to be a reincarnation of Tsongkapa, the reformer and virtual founder of the Geluk school.

One consequence of

this pre-Buddhist legacy was a sense of place. Buddhism, in common with most of

the major faiths, is a universalist, evangelical religion, intended to be heard

and practised worldwide. In Mongolia, however, religious

practice was deeply tied to locality, and to a semi-nationalistic,

semi-mystical notion of the country. Mongolian rituals were often linked with

binding or controlling the spirits of the land, keeping them simultaneously

imprisoned and appeased. A typical example could be seen in the scattered ovoos, stone cairns which both paid homage to the spirits

of a place and signified the Mongolians' connection to their land. Mongolians

travelling abroad, particularly those going on pilgrimage to other holy sites

in Tibet or Nepal, would tie blue ribbons or scarves to the ovoos,

remembering themselves to their country before leaving. Certain places were to

be avoided altogether, for fear of offending the spirits. Lu, the river

spirits, were particularly given to entering trespassing swimmers through their

urine, poisoning their bodies.

There was a constant

sense of the fragility of humanity. The spiritual world was in a state of

conflict between malevolent and benevolent spirits, in which humanity played

only a small part. Regular intervention with the spirits and gods was necessary

in order to ward off catastrophe. The lamas played an intercessory role they

had inherited from the shamans, praying to, pleading with, and sometimes

commanding other-worldly figures. The difference between the lamas and the

beings they interacted with sometimes became blurred; during rituals they could

appear to be possessed by the gods themselves, and some of the semi-secret

mystical paths involved the merging - or spiritual consumption - of the

initiate and his patron deity. In Mongolian popular legend, then, the lamas

were sometimes sharpsters and cheats, sometimes wise

men, and sometimes threatening, powerful figures in their own right.

In reality, then as

now, lamas were equally varied. Mongolian lamas did not reach the same extremes

as their Tibetan counterparts, where some monasteries were notorious bandit centres and others famous for their charity and wisdom, but

some Mongolian monks were clearly in it for everything they could get, some

were just happy to have a relatively secure berth, and some were saintly,

generous figures who used their wealth to help the poor.

For ordinary Mongolians, the terrors of the spiritual world were offset by the

security it offered. Living on the hard steppe and at themercy

of plague, weather and bandits, any form of control, no matter how illusory,

was comforting. For the destitute widows and scavengers who made up so much of

the population of Urga, the possibility of spiritual

salvation was perhaps the only hope left. It could also assert humanity and

happiness; the rituals, no matter how menacing, contained an element of

celebration and glamour.

It is likely that

most Mongolians did not live in the state of spiritual paranoia that a cold

reading of their belief system might indicate. Today, after all, we live in a

world of invisible, intangible life forms that can, if we fail to observe the

proper rites and taboos, strike us down with uncomfortable, agonising

or even fatal results. A few people are obsessed and terrified by these beings,

but most of us merely make sure we wash our hands and then forget about them

most of the time. The Mongolian attitude towards the spirit world was, perhaps,

often the same as ours towards bacteria: a fixation for some, a living for

others, just part of everyday life for most.

The terrifying nature

of some of the images was also somewhat diluted by their entertainment value.

The fear they inspired was part of the thrill, and even the most serious

rituals could also be an excuse to party. There was aesthetic pleasure there,

too; virtually all Mongolian art was religious and much of the more transitory

art, such as banners and paper hangings for poles, was produced communally.

Although it was usually more vivid than beautiful, it gave people an

opportunity to express and enjoy values that didn't otherwise feature on the

steppe.

Some of the enj oyment was a little more

prurient; the religious art occasionally strayed into outright pornography, and

even the most devoutly depicted female deities were often remarkably nubile.

The temple of the Mongolian state oracle contained a private building full of

images of divine couplings, where, according to the temple records, it was

possible to 'meditate upon the secret Tantra'. 28

Such comforting,

reassuring, occasionally erotic aspects of Mongolian religion were unfathomable

to most Western observers. European visitors to Mongolia regarded its religious

medley and semi-theocratic society with a mixture of contempt and fear. On the

one hand Mongolians were superstitious, priest-ridden, ignorant, fanatical,

classically heathen. Those travellers who had some

knowledge of Buddhism tended to look down on the Mongolians as practising a debased version of what they saw as a

philosophical and refined religion. On the other hand, Mongolian religion was

seen by outsiders as both frightening and powerful. Certain phrases recur in

the European accounts: 'hidden powers', 'strange and dreadful things',

'demon-haunted land', 'mysterious abilities' and so on.

These occult

fantasies were related to the fear of the rise of the East expressed by so many

thinkers of the time. The mirror image of these nightmares of oriental