The premise is

straightforward: A digital or paper document will indicate whether individuals

have received a COVID-19 vaccination or, in some cases, recently tested

negative for the coronavirus. This could allow them to travel more freely

within their communities, enter other countries or engage in leisure activities

that have largely been closed off during the pandemic.

Qantas was the first

airline to announce it will require international passengers to be

vaccinated.

How you’ll prove,

your vaccination status is still being figured out. Fake COVID test documents

are already a problem, as assurance that the person who took the test is the

same one brandishing the certificate.

Several “vaccine

passports” are being marketed, but CommonPass looks the most promising. A collaboration

between the World Economic

Forum and

nonprofit The Commons Project, CommonPass is a secure way

to validate individuals’ COVID test and vaccination credentials and is being

piloted internationally. The first

government to sign on to the CommonTrust Network was

Aruba, allowing travelers

to securely prove their COVID status to enjoy its Caribbean beaches by February

2021.

Needle to say

COVID-19 vaccines are one of the world’s hottest commodities, which means

people with money or status will try to jump the queue. Most nations say their

vulnerable citizens, essential workers and the elderly, get it first. Still,

politicians were among the

first to roll up their sleeves in the U.S., and the rich are

offering donations in

hopes of skipping the line.

This week the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention issued the first

guidance on what vaccinated people can do. More is needed. True, covid-19 is

still poorly understood, and individuals' risk will depend on their own

circumstances. Yet the data that is currently available already cast some light

on what puts you at risk if you are diagnosed with the disease. Age is closely

tied to death, so do not visit your unvaccinated grandparents, however healthy

they may be. Comorbidities can lead to a spell in the hospital, even for the

young, so don’t imagine you are safe just because you’re under 35. More work

like this will be needed for people to make informed decisions about covid-19,

just as they do for the rest of their lives.

Papers, please

Worried about stalled

economies and restive citizens, governments thus have leaped on the idea of

“vaccine passports” as a way to free at least some people from lockdowns. In

January, Joe Biden, America’s president, ordered his government to assess the idea.

On 8 March, the country’s guidelines about social mingling were updated to

distinguish between the vaccinated and unvaccinated for the first time. The

European Commission will put forward plans for a bloc-wide “digital green

pass” on 17 March Britain is considering a vaccine-passport scheme

too. In some versions of the idea, the passports would include not just

vaccination status but results from infection tests, proof that the bearer had

completed a period of quarantine or exemptions from vaccination for health

reasons.

Vaccine-related

restrictions are not a new idea. Visitors to places where yellow fever is

endemic have to prove vaccination with a “yellow card.” Immigrants to America

must be vaccinated for 15 diseases listed by that country’s Department of

Health before they can become permanent residents. So must children in all 50

states before attending public schools (though there are exemptions for the

immuno-compromised and religious objections). In many places, similar rules

apply to some health-care workers and soldiers.

America, Britain, and

the European Union are all studying how they might be made to work. Angela

Merkel, the German chancellor, has spoken up for them. Israel, where

vaccination is advanced, already has such a system.

Vaccine passports

have their uses, especially in international travel, but they are unlikely to

be as helpful as their supporters imagine at home. To see why to consider two

extremes. When nobody is vaccinated, passports obviously serve no purpose. Yet,

outside a dictatorship, they are not terribly useful at the end, when everyone

who wants a jab has had one. If vaccines are free and widely available,

unvaccinated people are choosing to risk infection. Those who cannot be

vaccinated face extra risks from covid-19, just as they do from other diseases.

Passports are most useful in the period when large numbers of people who want

to be inoculated risk being infected because the vaccine is scarce. That is

also when passports are most unfair.

For international

travel, this window could remain open for years. Countries with a large tourism

industry can use passports to protect their people from visitors bringing in

disease. Even if global vaccine distribution raises ethical questions, the passport

system itself presents none that are new because it is already established for

diseases like yellow fever.

Britain plans to have

all adults vaccinated by the end of July. America will have enough doses to

finish soon after. Even in Europe, where inoculation

has been slow, a

sweeping vaccine-passport system may not be worth the cost or the hassle.

Supporters argue that

passports are an incentive for people to be vaccinated. If they are

well-designed, they need not pose a threat to personal data; nor need they

become a platform that the state later uses to intrude into citizens’ general

health. However, the more heavily passports are used as an incentive, the more

they are oppressive. If you need one to get on a bus or buy a loaf of bread,

you lose your choice to be vaccinated. Most employers should have no use for

them. Better to encourage people to get a jab.

That leaves two

reasons for passports at home. One is to enforce vaccination when infected

people could harm those who have had their jabs in hospitals and care homes,

for example, rather as some countries already require proof that those working

with vulnerable people have no criminal record. The other is an insurance

policy against the possibility that boosters must deal with variants say.

Countries have often looked for magic solutions to stop the pandemic. The only

one that promises to succeed is not passports; it is vaccines.

A ticket to freedom?

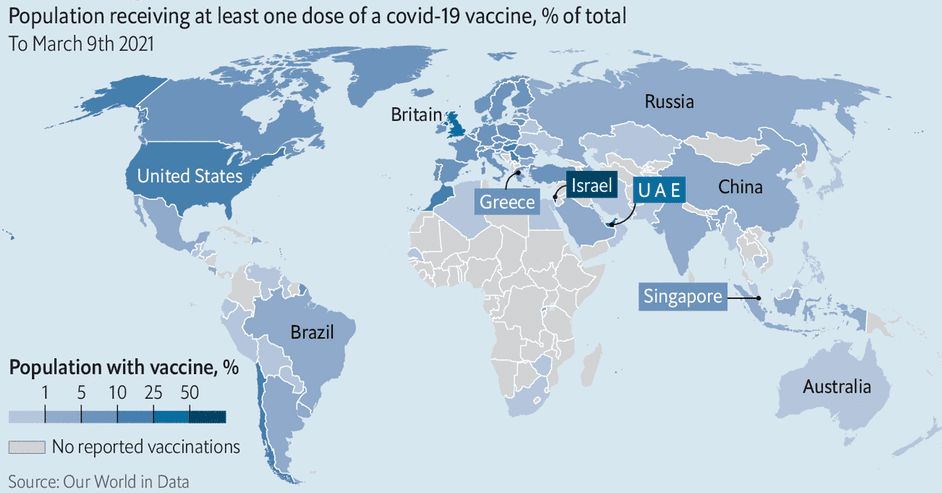

Precisely because

countries are vaccinating at drastically different rates, covid passports could

come into their own for international travel. Even as America, Britain, Israel,

and a few other countries sprint towards herd immunity, only 7% of eu citizens have had their first jab. In some poor

countries, vaccination is likely to continue until 2023 or 2024. Without a way

to speed the vaccination through airports, the world will remain locked down

even if some individual countries do not.

Many countries are

therefore poised to incorporate vaccine passports into their entry rules, says

Nick Careen of the International Air Transport Association (iata),

an airline industry group. Ordinary people are desperate to see family and

friends abroad and to go on holiday. Within the eu,

Greece is the strongest supporter of a bloc-wide vaccine passport. Before the

pandemic, tourism accounted for a fifth of its gdp.

Its hotel owners and restaurateurs hope that vaccinated tourists could help

rescue their summer season.

Several nations have

already cobbled together systems designed to allow at least a bit of travel to

continue. They require a negative covid-19 test before setting off and

quarantine upon arrival. These work in only the narrowest sense. Quarantine

deters all but the most desperate (or footloose) travelers. They can be hard to

manage. After Britain tightened its rules in January, passengers arriving at

Heathrow, its biggest airport, took many socially un-distanced hours to

traverse the queues. If vaccine passports lack standardized verification

procedures could be chaotic.

IATA hopes its Travel

Pass project will come to the rescue. Under development before the pandemic, it

aimed to speed up airport transit by making use of biometric information and

secure digital identifiers on passengers’ phones. It relies on Timatic, IATA's database of visa and entry

regulations, which is already used by travel agents, airlines, and airports. On

a normal pre-covid-19 day, the database needed updating a handful of times. At

the height of the pandemic, as governments scrambled to keep out travelers from

places with high infection rates and new variants, that spiked to above 200.

Travel Pass is being

tested as a stand-alone app and as a chunk of code that airlines can use in

their own apps. Several, including Emirates, Etihad Airways, and Gulf Air, have

signed up to test it. Other bits of the travel industry, such as cruise lines

and resorts, could use it too. They hope that one silver lining of the pandemic

might be to speed the arrival of seamless, document-free travel. In ordinary

times, he says, that would have required a battery of trials and tests with

many different governments. Instead, the pandemic has persuaded countries of

the virtues of co-ordinated standards, practically

overnight.

Making passports work

internationally, though, will be even harder than making them work within

countries. IATA says that testing laboratories and health-care

providers will have to be certified, as travel agents currently are.

Vaccination will take the longest in poor countries, here such verification

will also be hardest. Incentives to cheat will be high. Europol, the

EU's police agency, says fake covid-test certificates have already started

to turn up at borders.

And some of the

trade-offs visible inside countries are even starker when considered between

them. One is between lowering infection rates and rising economic activity.

Vaccinated British holidaymakers visiting Greek beaches will need locals to

pour their retsina. Unvaccinated hospitality workers brought out of furlough

will catch the disease from each other, if not from visitors.

The world’s poorest

countries will have to choose between tourist cash and social mixing, on the

one hand, and higher rates of infection, sickness, and death, on the other, and

not just this year, but for several years to come. When big new policy problems

arise, governments are attracted by technical fixes that promise a speedy

return to the status quo ante whereby one also should focus on clearer

communication regarding risks, and on measures that would enable gradual

reopening for everyone as the number of infections falls.

A world divided?

Perhaps the biggest

unknown of vaccine passports will be the psychological impact they have. After

a year in which few people have crossed a border, and some have barely left

home, many may have become more risk-averse. Would a scheme that liberates

vaccinated people to mingle with each other provide valuable, though temporary,

reassurance on the road to herd immunity? Or would it slow down the return to

normality by suggesting to the newly fearful that their fellow citizens are a

permanent threat?

Thus when it comes to

covid-19, not everyone is so keen. Policy experts argue that, in many

countries, vaccination is moving quickly enough that passports will be only

briefly useful. Civil libertarians and security researchers worry that

governments may be tempted to misuse the data and exploit the control they

grant over people’s lives. Public-health experts say it is too early to know

whether the idea is medically sound. Vaccines offer potent protection

from sars-nov-2, the virus that causes covid-19. Although it looks very

much as if they also significantly cut transmission, that is not yet certain.

Any policy must grapple with questions of fairness and coercion, private

approaches to risk versus communal ones; trade-offs between infection and

economic activity; and the question of what lockdowns have done to people’s

psyches.

Security is a good

place to start, for if passports are to work, they must be trustworthy.

Researchers who examined Israel’s app found several flaws. Problems with the

first version of the app meant that clever fraudsters could sell fake

certificates online. The moving image in the latest version was supposed to

improve security but can still be copied.

Nosy governments are

another risk. Last year Singapore pledged that data from its contact-tracing

app would be used for no other purpose. In January, it said that, in fact, the

police had been granted access for crime-fighting. That was enough to annoy even

Singapore’s usually compliant citizens. Vivian Balakrishnan, a Singaporean

minister, said he took “full

responsibility” for what he called a “mistake.”

In China, compulsory

health apps use location data from smartphones to produce qr codes that determine whether someone is free to

enter many indoor spaces and travel without restrictions. Tracking data appear

to be shared with police. The risk calculations are a black box, and the code

seems glitchy. Even after a mandated quarantine period is over, the apps may

not update to reflect that fact for days. Even so, they look likely to become a

permanent fixture.

Incompetence and

snooping could taint the whole idea of vaccine passports and provide grist to

covid-conspiracists’ mill. But privacy worries are not insurmountable. David

Chadwick, formerly a computer-science professor at Kent University in England,

is the boss of a spin-off company called Verifiable

Credentials. Before the covid-19 pandemic, his firm worked on a

privacy-focused scheme for workplace identity cards, parking permits, concert

tickets, and the like. “I wasn’t thinking about health applications at all,” he

says. These days covid-19 is his priority.

The idea is to ensure

no connection between the source of a person’s vaccination data and the entity

requesting it. Individual users are linked securely with their smartphones

using biometrics and some form of a government-issued identity document, a process

similar to registering for mobile banking. A user seeking entrance to a

“covid-secure” venue would have entry rules transmitted to their phone at the

door. The app would check those rules against the user’s data and spit out a

simple “yes” or “no”, and nothing else. Specifics such as a person’s name, age,

address, the date of their vaccination, and the like would not be reported,

limiting the opportunity for mischief.

In April 2020,

Verifiable Credentials demonstrated that its prototype would verify vaccine

status and covid-test results as soon as those things existed. Its app is being

tested with dummy data at a cinema that actors are using as a rehearsal space

and with real data at a British hospital, replacing existing paper-based

methods. The firm is also working on a physical version for use by those

without smartphones.

As further detailed

below public-health bodies fret about the perceived fairness of what vaccine

passports would enable. Most countries have put the elderly at the head of the

queue for vaccination since they are most likely to die from covid-19. Passports

raise the prospect that vaccinated pensioners will be allowed to roam freely

while the young, who have been confined to quarters largely to protect their

elders, remain under lockdown.

In some countries,

those worries may be heightened by racial implications. Black Americans are

more dubious about vaccines than white ones, and some who want jabs find it

harder to get them. They are also, on average, younger than their white

compatriots, which means they are further back in the queue. When vaccine

roll-outs are fast and free, and priorities are set justly and transparently,

equity questions will be transient. But in countries where politicians

queue-jump or herd immunity is years away, they may cause resentment.

Then, there is the

question of what to do with those who cannot or will not be vaccinated.

Governments will be under pressure to grant exemptions, especially for medical

contra-indications. But each unvaccinated person allowed into supposedly

covid-safe spaces would make them less so. Another worry is that the

unvaccinated could become less employable. A global survey by Manpower, a

recruitment agency, published on March 9th found that a fifth of employers

planned to start mandating vaccination for at least some roles, and another 14%

were undecided. As soon as herd immunity has been reached, it makes little

sense for employers to care about such matters, but some may, especially if

customers keep asking. That could make vaccines close to compulsory.

The most fundamental

criticism is that it remains unclear whether vaccine passports will even do the

job they are supposed to. On 5 February a paper from the World Health Organisation (who) argued that vaccinated people should not

be exempt from lockdown and quarantine rules. It said that using vaccine

passports for border crossings would be “premature” (though it is so sure this

is imminent that it is nevertheless drawing up suggestions for how best to do

it). On 17 February, the Ada Lovelace Institute, a think-tank that is

tracking vaccine passports proposals globally, concluded that they are not

currently justified.

One reason is that,

although existing vaccines seem very effective at preventing illness, it is not

clear whether they completely prevent infection with the virus or remove the

ability to transmit it to others. (One paper published in June, before any vaccines

were available, estimated that more than a third of those infected with

covid-19 display no symptoms but can still infect others.) There are some

encouraging signs. A leaked draft of a paper put together by Pfizer and

Israel’s health ministry suggests that receiving both doses of the

Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine cuts asymptomatic cases of covid-19 by nearly 90%.

Another paper, published by researchers at Cambridge University Hospitals nhs Foundation Trust, but not yet peer-reviewed,

looked at asymptomatic health-care workers at a British hospital. It found that

a single dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine cut asymptomatic cases by 75%

after 12 days. But the evidence is not yet strong enough to convince wary

public-health officials.

Another reason is

that mutations in sars-nov-2 mean that whatever conclusions are arrived at

today might change in the future. Scientists hope that existing vaccines should

be able to deal with the virus's variants that have arisen thus far. But a novel

variant against which they are less effective could emerge at any time. New

vaccines would almost certainly be developed swiftly. But until they were

deployed, a much bigger job, passport systems would be useless.

The final point is

that the usefulness of a vaccine-passport system is inversely related to how

quickly a country can vaccinate its citizens. Early in a vaccination program,

few people would benefit. Towards the end, the passports would be of little

help. In countries such as Israel, where vaccination is proceeding rapidly, the

span of time during which passports are useful could prove quite short. In

those countries where vaccine roll-outs are slow, it may be needed as a crutch

for longer.

Conclusion

As thus explained

above there are a number of reasons for concern. For example also given the

global imbalance of vaccine availability, it is not difficult to imagine a

situation where the citizens of rich countries may regain their rights to

travel to environments where local populations are still in some form of

lockdown.

This potential to further

divide the global rich from the global poor is a significant concern. Once

economies start to “open” and those with vaccine passports are able to go about

their business, as usual, the urgency to deal with COVID-19 in marginalized

communities may dissipate. The average citizen in a high-income country is much

more likely to receive a vaccine than a healthcare worker or high-risk citizen

in lower-income countries.

Further, vaccination

passports may give populations an inaccurate

level of risk perception. It is still unclear how

long immunity will last. It is also unclear the extent to which virus transmission

is limited once one is vaccinated. Public

health authorities still suggest that vaccinated individuals wear masks and

maintain distancing in public for now, especially if interacting with

unvaccinated people. These recommendations have led to concerns that vaccinated

tourists, diners and shoppers may act in ways that might risk the unvaccinated

service and hospitality employees with whom they are interacting.

There are also

privacy concerns with vaccine passports, which are primarily being proposed in

a digital format. In the U.K., the proposed vaccine certification would come in

the form

of an app, which could be scanned to gain entry to restaurants and venues.

It has sparked

concerns that digital passports may infringe on the rights to privacy,

freedom of movement, and peaceful assembly.

Countries that rank

low in global freedom indexes, such as Bahrain,

Brunei and China,

are also using apps, often with troubling implications. In China, the app was

found to be linked to law enforcement, and as people checked in to locations

across the city, their locations were tracked by the software.

Despite the upsides

of vaccine passports, these concerns remain. The World

Health Organization has called on nations to make sure that, if

implemented, vaccine passports are not responsible for “increasing health

inequities or increasing the digital divide.”

For updates click homepage here